Introduction

Diabetes is a disease with skyrocketing prevalence. The number of ~280 million patients today will increase to ~450 million in 2030. Therefore, new approaches to research and development (R&D) in the pharmaceutical industry are needed in how we work and what we work upon.

New ways of working together in R&D

The ‘how’ mentioned above is not specific for new ways of working in R&D for antidiabetic drugs but includes new ways of cooperating with external partners, particularly small biotech companies, academic organizations and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), independent from the indication. However, as the number of diabetes patients increases continuously all around the world, there is a huge need to find new solutions for this disease, requiring a joint effort from all scientists and institutions working in the area. Joint efforts include partnerships as described above. They have to be focused on common projects driven by a common enthusiasm, common teams consisting of scientists on both sides, exchange of scientists between the cooperating organizations and common laboratories. In general, win/win situations have to be generated, in the sense that each partner is responsible for those activities in which it is specialized. As an example, some new targets will come from outside of the laboratories of big pharmaceutical companies, but the validation of the target and the translation of the target into a molecule interacting with it is a strength of the pharmaceutical industry. Screening of huge libraries, optimization of molecules regarding efficacy and safety (including early absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination [ADME]), production of large amounts of molecules for preclinical and clinical studies as well as other preclinical and clinical development activities are typical assets of the pharmaceutical industry.

For this reason, many cooperations between big pharmaceutical companies (Lilly and Boehringer as examples), between big pharmaceutical companies and smaller Biotech companies (Boehringer and Zealand as an example) and between pharmaceutical companies and academia (Sanofi and Charité as an example) are already working on new targets and approaches.

New R&D approaches in diabetes

The ‘what’ mentioned above includes promising new targets and molecules that are already in the R&D process. One example of new very early targets is osteocalcin (OCN), which in its undercarboxylated form (uncOCN) seems to have positive effects on the metabolic syndrome, including improvement of insulin resistance, β-cell function and dyslipidemia. uncOCN or analogs could be used as an injectable drug, or small-molecule agonists could be generated. In essence, uncOCN is a very early target but has a potential to create a paradigm shift by regarding the skeleton not only as a stable physical frame, but also as an endocrine organ influencing and coregulating the metabolic activities of the body.

Another highly innovative target is INDY. Its deletion mimics aspects of dietary restriction and protects again adiposity and insulin resistance in mice. Its name is based on the abbreviation of ‘I’m not dead yet’, which is related to a considerably longer life span based on reduced expression of the INDY gene in Drosophila melanogaster and its homolog in Caenorhabditis elegans [Birkenfeld et al. 2011].

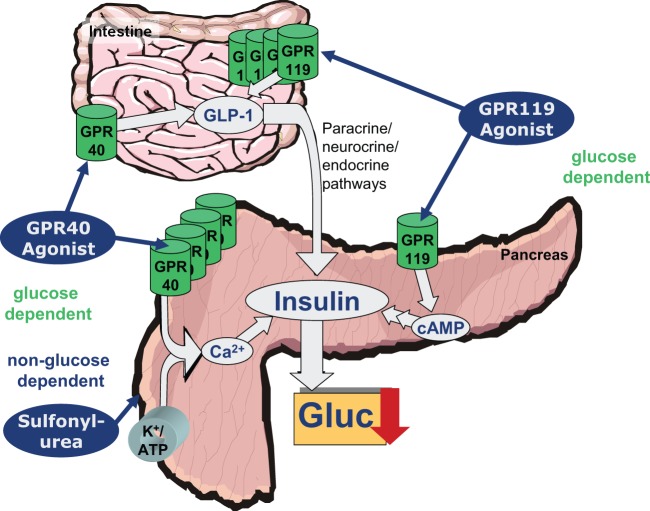

Examples of targets that have already reached the preclinical phase are the agonism of GPR119 and GPR40, the latter even having clinical proof of concept. In contrast to a treatment with sulfonylureas, agonism of GPR119 and GPR40 is a glucose-dependent process, without risk of hypoglycemic effects (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of GPR40 agonist, GPR119 agonist and sulfonylurea pathways.

GPR119 projects are mainly in preclinical phases, with some reports regarding clinical effects not being completely convincing so far. By contrast, GPR40 agonists have already demonstrated a significant clinical effect, indicated by a HbA1c decrease in the range of 1% without any hypoglycemic side effects following a treatment duration of 12 weeks [Burant et al. 2012].

A new tendency in the treatment and prevention of diabetes involves the use of antibodies, especially in the area of type I diabetes. For diabetes prevention, lowering of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) plays an important role for prediabetic patients. Despite the existing statin therapy, which will become generic very soon, new biological approaches will play an important role in the future. One critical question in this area is the acceptance of injections by patients and doctors for the purpose of LDL lowering, when pills for an identical purpose are also available. Therefore, longer injection intervals and an effect on top of existing oral therapies are mandatory for the success of these kinds of drugs.

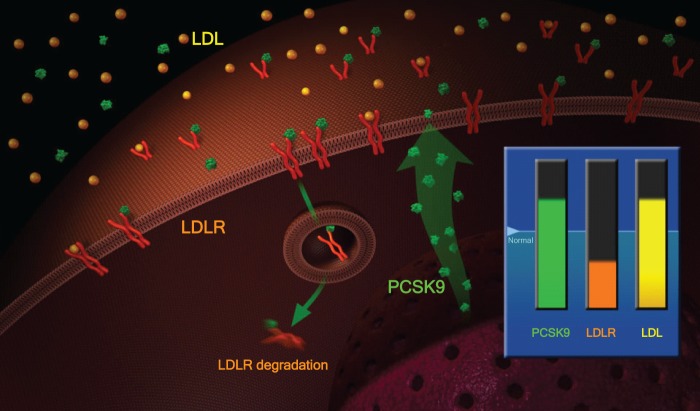

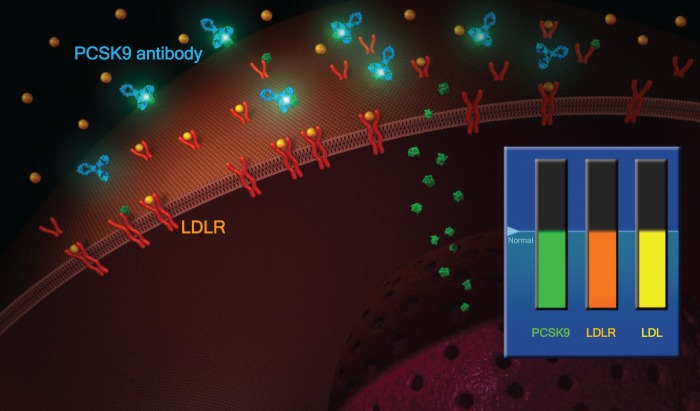

One example of such a promising target is the Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 (PCSK-9), which regulates the amount of LDL receptors on the surface of hepatocytes: PCSK9 binds to LDL receptors, leading to their accelerated degradation and thus to increased LDL cholesterol levels (Figures 2 and 3). It is known that populations with a loss of function mutation in PCSK-9 have considerably lower LDL levels and a lower incidence of coronary heart disease [Cohen et al. 2006]. An antibody against the PCSK9 given every 2 or 4 weeks is able to reduce LDL plasma levels by ~60–70%, even on top of statins [Swergold et al. 2011].

Figure 2.

Physiology of PCSK-9: increased PCSK9 leads to lower LDLR.

Figure 3.

Physiology of PCSK-9: increased LDLR reduces LDL.

Other trends in diabetes R&D

The PCSK-9 antibody is an excellent example of translational medicine, which will become more and more important in the diabetes area as well: starting with an observation of a specific ‘knock-out population’ with a dysfunctional protein, its pathophysiological role resulting in a specific pharmacological effect could be clarified and rapidly translated into the human situation. The proof of concept was demonstrated impressively in a small phase I study [Swergold et al. 2011]. Similar ways of working will become standard in the pharmaceutical industry to avoid an entry into bigger clinical studies with any ‘black-box situation’.

In addition, we will see an increasing personalization in the treatment of diabetes. Until today, all diabetic patients have been treated with a schedule that is more or less only dependent on the disease status. It starts with ‘diet and exercise’ (which is mostly ignored), followed normally by metformin and ends with various insulin regimens. Stratification of patient populations is still difficult, but clearly on the agenda for the near future. For this purpose, several activities have already started, an example of which is the Innovative Medicine Initiative under the umbrella of the EU, which has a subprogram called DIRECT that deals directly with personalized approaches for the treatment of diabetes. It will be driven by increasing genetic information coming from genotyping of diabetic patients, but phenotyping activities will play an important role as well in diabetics. Because diagnosis will be absolutely mandatory for personalized medicine, integrated solutions including diagnosis and drugs will play an increasing role in the future. In cases of biological drugs, this will often also involve the appropriate device being codeveloped with drug and diagnosis.

The last aspect to be addressed in the diabetes area is the improvement of patient convenience, for example the innovative painless needle-free administration of insulins and other peptides, or by new discrete monitoring systems that are fully compatible with modern electronic devices, such as smart phones or tablet computers.

Conclusion

Summarizing the newest trends in antidiabetic drug development described above, it is very likely that we will see a significant chance of success in diabetes R&D to fight the burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus as an upcoming global disease, a promising process which has already been started. Furthermore, we will experience a tremendous change in the way the different players in health care and drug development will work together in the future:

— between companies;

— between academia and big pharmaceutical companies;

— between big pharmaceutical companies and small biotech companies;

Furthermore, there are several new targets to be evaluated coming from different sources. Translational medicine will play an increasingly important part in diabetes R&D, as well as personalized approaches, which require biomarkers/diagnosis (not necessarily genetic). In the future, the ‘complete’ package for the diabetic patient will increasingly involve ‘diagnosis+drug+device’.

References

- Birkenfeld A., Lee H., Guebre-Egziabher F., Aleves T., Jurczak M., Jornayvaz F., et al. (2011) Deletion of the mammalian INDY homolog mimics aspects of dietary restriction and protects against adiposity and insulin resistance in mice. Cell Met 14: 184–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burant C., Viswanathan P., Marcinak J., Cao C., Vakilynejad M., Xie B., et al. (2012) TAK-875 versus placebo or glimepiride in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 379: 1403–1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., Boerwinkle E., Mosley T., Hobbs H. (2006) Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 354: 1264–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swergold G., Smith W., Mellis S., Logan D., Webb C., Wu R., et al. (2011) Inhibition of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 with a monoclonal antibody REGN727/SAR236553, effectively reduces low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol, as mono or add-on therapy in heterozygous familial and non familial hypercholesterolemia. Circulation 124: A16265 [Google Scholar]