Abstract

We conducted a coordinated biochemical and morphometric analysis of the effect of saline conditions on the differentiation zone of developing soybean (Glycine max L.) roots. Between d 3 and d 14 for seedlings grown in control or NaCl-supplemented medium, we studied (a) the temporal evolution of the respiratory alternative oxidase (AOX) capacity in correlation with the expression and localization of AOX protein analyzed by tissue-print immunoblotting; (b) the temporal evolution and tissue localization of a peroxidase activity involved in lignification; and (c) the structural changes, visualized by light microscopy and quantified by image digitization. The results revealed that saline stress retards primary xylem differentiation. There is a corresponding delay in the temporal pattern of AOX expression, which is consistent with the xylem-specific localization of AOX protein and the idea that this enzyme is linked to xylem development. An NaCl-induced acceleration of the development of secondary xylem was also observed. However, the temporal pattern of a peroxidase activity localized in the primary and secondary xylem was unaltered by NaCl treatment. Thus, the NaCl-stressed root was specifically affected in the temporal patterns of AOX expression and xylem development.

Salinity is an environmental stress that limits growth and development in plants. The response of plants to excess NaCl is complex and involves changes in their morphology, physiology, and metabolism. Most studies have been descriptive and have not elucidated mechanisms by which salinity inhibits plant growth (Cheeseman, 1988; Munns, 1993). There are multiple genes that seem to act in concert to increase NaCl tolerance, and certain proteins involved in salinity stress protection have been recognized (Bohnert and Jensen, 1996; Hare et al., 1996).

Within any organ there exists a range of both cell types and cell ages and, therefore, the metabolic functions and the responses to environmental stimuli may be expected to vary with these different patterns of localization and developmental stages. Plant roots provide an attractive experimental system for investigating salinity effects on growth and other parameters for the following reasons: (a) they have a definable growing region in the tip and a separate nongrowing region consisting of mature, elongated cells, some distance behind the tip (Ishikawa and Evans, 1995); and (b) root cells can be directly exposed to different NaCl concentrations by changing the root medium.

Previously, it was reported that excess NaCl in the growth medium induces structural changes in bean roots, as well as leakage of ions correlated with alterations of the cell membranes (Cachorro et al., 1995). It was also reported that NaCl treatment leads to changes in the lipid composition of bean roots (Cachorro et al., 1993; Zenoff et al., 1994; Surjus and Durand, 1996) and affects the proton-extrusion activity, which appears to be partially dependent on a H+-ATPase associated with the plasmalemma (Zenoff et al., 1994).

Knowledge about respiratory metabolism during saline stress is scarce (Fernandes De Melo et al., 1994). In this context, the role of the nonphosphorylating alternative pathway, which is a common feature of higher plant respiration (Moore and Siedow, 1991; Siedow and Umbach, 1995), has not been elucidated. This pathway can be induced by a number of treatments generally described as stress conditions, and thus it was suggested that the AOX pathway may be part of a stress response in plants (Purvis and Shewfelt, 1993; Day et al., 1995). The participation of the AOX pathway in response to NaCl stress has been analyzed in barley leaves (Jolivet et al., 1990), but the reported data are difficult to interpret in part because they were based on considerations, the validity of which has been questioned (Millar et al., 1995; Day et al., 1996).

An approach toward understanding the mechanisms of saline effects in young roots is to follow the time course of a series of biochemical, physiological, and structural events in the early stages of development. We studied the effect of NaCl treatment on the differentiation zone of developing soybean roots by analyzing the temporal evolution of AOX capacity and peroxidase activity, in correlation with the tissue localization of these enzymes and NaCl-induced structural changes. These coordinated analyses during a defined growth period revealed that saline stress specifically delays or advances the temporal evolution of determined parameters and has no effect on the temporal pattern of others, leading to a plant that is not only smaller than the control but also with different biochemical and morphological characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth and Saline Stress

Soybean (Glycine max L. var UFV-8) seeds were germinated for 3 d at 28°C in sterile sand that was moistened with tap water. Then the seedlings were transferred to hydroponic culture in 25% Hoagland medium supplemented with 120 mm NaCl (saline stress) or without the NaCl supplement (control). Plants were grown at 28°C under greenhouse conditions and harvested when indicated for each experiment during the period between d 0 (sowing) and d 14 of development. The nutrient medium was renewed every 3 d. This standard protocol was followed for all of the experiments, except for that experiment whose results are shown in Figure 3.

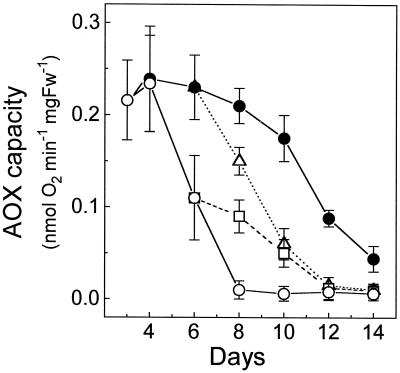

Figure 3.

Temporal evolution of AOX capacity in the differentiation zone of roots from seedlings grown in sand containing control (○) or NaCl-supplemented (•) Hoagland medium from d 0 to 12. Each value is the mean ± sd of two separate measurements. Fw, Fresh weight.

In the experiment shown in Figure 3, the seedlings were germinated and grown (at 28°C) in sand containing control or NaCl-supplemented Hoagland medium (140 mL/kg sand) over the whole period from 0 to 12 d of development. The sand was periodically moistened with distilled water.

Selection of the Root Region Studied

The differentiation zone of the primary root was studied. To verify that the selected zone from both the control and stressed roots was identical at the different developmental stages, a segment about 4 mm long was marked gently with a pen in the differentiation zone of the primary root in 3-d-old seedlings grown in parallel with those used for the biochemical and morphological analyses. One-half of the marked seedlings was transferred to the control medium and the other half was transferred to the NaCl-supplemented medium, and the localization of the selected segment was observed during the following growth period. This segment remained without substantial length change and was localized almost in the middle of the primary root in both the control and the stressed seedlings over the period studied.

Assays of AOX Capacity and Peroxidase Activity

AOX capacity was measured as described previously (Hilal et al., 1997) in slices of the selected segment from the primary root-differentiation zone of control and stressed seedlings during the growth period between d 2 and 14.

Peroxidase activity was determined in extracts of the selected root segments, as described by Peyrano et al. (1997), using the substrate syringaldazine. The specific activity was expressed as the increase in A530 per minute and milligram of protein. Protein concentration was measured by the procedure of Lowry et al. (1951).

Tissue Prints

Tissue printing of cross-sections from the differentiation zone of primary roots (selected as indicated above) and specific immunostaining with anti-AOX monoclonal antibody were performed as described previously (Hilal et al., 1997) at d 8 of plant growth under control or saline conditions.

Tissue prints of the same root zone were also made on d 3 and d 10 of control and stressed seedlings to detect activity of syringaldazine oxidase, a peroxidase associated with lignification (Goldberg et al., 1983). The assay conditions were as described by Peyrano et al. (1997)

Mophometric Analysis of the Root-Differentiation Zone

The selected segments from the root-differentiation zone of control and stressed seedlings were fixed in filtered control or NaCl-supplemented Hoagland medium, respectively, with 3% glutaraldehyde for 6 h at 4°C and then postfixed overnight with 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). The samples were dehydrated with a graded series of ethanol, ending with 100% acetone, and then embedded in Spurr's medium (Spurr, 1969) and polymerized overnight in a 60°C oven. Cross-sections (0.5 μm) were prepared with an ultramicrotome and stained with toluidine blue (Richardson et al., 1960) before visualization with a light microscope.

The number of xylem vessels and the areas occupied by the xylem and phloem in the stele and the intercellular-to-cellular-area ratios in the cortex were determined from images of the root cross-sections digitized with a charged-coupled device 200E video camera (Videoscope International, Washington, DC) coupled to a Macintosh Quadra 700 computer. Image analysis and quantitation were performed with NIH Image 1.45 software (Rasband W, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

RESULTS

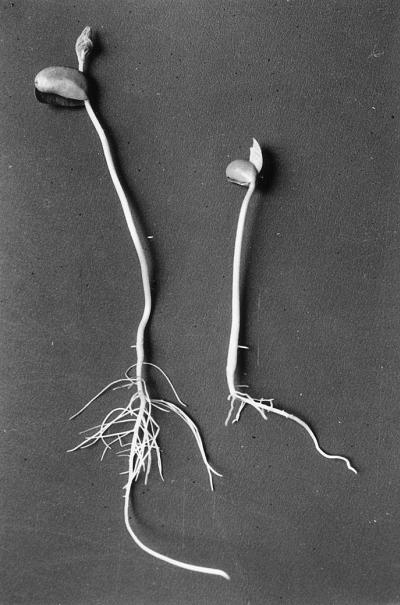

Figure 1 shows the appearance of control and NaCl-stressed seedlings at d 8 of growth. Roots of plants treated with NaCl were shorter and had fewer secondary roots than the controls. Saline stress decreased the growth rate of soybean seedlings, a well-known phenomenon.

Figure 1.

Control (left) and NaCl-stressed (right) soybean seedlings at d 8 of growth; magnification ×0.4.

Temporal Evolution of AOX Capacity in Control and NaCl-Stressed Roots

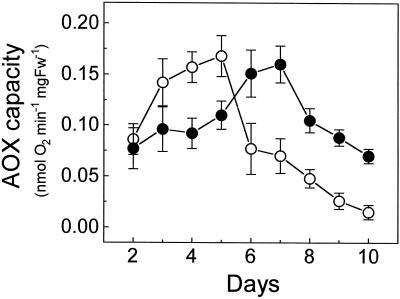

AOX capacity in the differentiation zone of control roots greatly decreased between d 3 and 8, as already reported (Hilal et al., 1997), whereas in the stressed roots AOX capacity remained high at d 8 (Fig. 2) and declined several days later than in the controls. At d 6 of development, when some of the stressed seedlings were transferred to the control medium, their root AOX capacity decreased earlier than that of the seedlings maintained in saline medium (Fig. 2). When some of the control seedlings at d 6 of development were transferred to the saline medium, they retained their root AOX capacity for a longer period than those remaining in the control medium. Results in Figure 2 show that saline stress delays the decline of AOX capacity in developing roots, but it does not induce an increase of this capacity.

Figure 2.

Temporal evolution of AOX capacity in the differentiation zone of roots from control (○) and NaCl-stressed (•) seedlings. At d 6 of growth, a group of the seedlings was transferred from the control to the saline medium (□) or from the saline to the control medium (▵). Each value is the mean ± sd of three separate measurements. Fw, Fresh weight.

In the experiment shown in Figure 2, saline stress was initiated at d 3 of plant growth when AOX capacity in the root-differentiation zone was highest (Hilal et al., 1997). A different protocol was followed in the experiment presented in Figure 3. In this case, the seedlings were grown on sand containing control or NaCl-supplemented Hoagland medium over the whole period from d 0 to 12 of development. As shown in Figure 3, AOX capacity in the differentiation zone of the control roots was maximal at d 3 to 5, whereas in the stressed roots the peak of AOX capacity was shifted to 2 d later. Thus, the temporal pattern of AOX capacity in developing roots is delayed by saline stress.

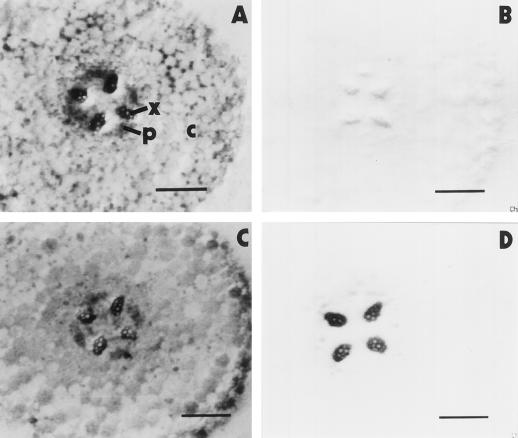

Localization of AOX by Tissue-Print Immunoblots

Control roots at d 8 showed no specific immunostaining in the differentiation zone using tissue-print immunoblots (Fig. 4B) because, as already reported (Hilal et al., 1997), AOX protein is no longer expressed at this developmental stage. However, in roots of NaCl-stressed 8-d-old seedlings, the xylem strongly reacted with the anti-AOX monoclonal antibody (Fig. 4D), indicating that AOX protein was still present in this tissue. This correlates with the delayed decline of AOX capacity in stressed roots (Fig. 2) and shows that the xylem-specific localization of AOX (Hilal et al., 1997) is conserved under saline stress. Figure 4, A and C, illustrates total protein, as evidenced by amido black staining of tissue prints from control and NaCl-stressed roots, respectively.

Figure 4.

Localization of AOX protein. Tissue prints of cross-sections from the differentiation zone of control (A and B) and NaCl-stressed (C and D) roots at d 8 of growth. A and C, Amido black stains of total protein. B and D, Immunostains specific for AOX. x, Xylem; p, phloem; and c, cortex. Bars = 250 μm.

Morphometric Analysis of Developing Roots

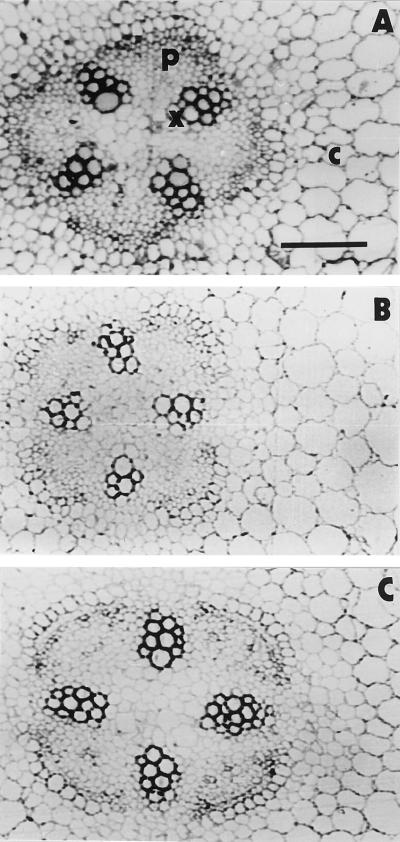

To determine whether the NaCl-induced delay in AOX expression was associated with retarded root differentiation, root anatomy was examined by light microscopy of cross-sections from the differentiation zone, which had been previously fixed and embedded. As shown in Figure 5, the most notable effect of the saline stress was to retard primary xylem differentiation. The appearance of protoxylem and metaxylem in the stressed roots at d 8 of growth was similar to that in the 3-d-old seedlings rather than to that in the control roots at d 8. This effect was quantified with an image analyzer and the data are summarized in Table I. The total area of the xylem in the cross-sections of the root differentiation zone was significantly smaller in the control 8-d-old seedlings than at d 3 of growth, whereas in the NaCl-stressed 8-d-old seedlings, the xylem area remained similar to that at d 3 of development. Also, the number of vessels remained constant in the NaCl-stressed roots, whereas the number decreased significantly in control roots between d 3 and 8 of growth. The changes in the xylem of control roots shown in Table I reflect the normal differentiation of protoxylem to metaxylem over the period between d 3 and 8 of plant growth. These changes did not occur in the NaCl-stressed roots, indicating delayed primary xylem differentiation.

Figure 5.

Anatomy of control and NaCl-stressed roots. Light photomicrograph of cross-sections from the differentiation zone of fixed and embedded roots. A, At d 3 (after germination in sand). B, Control at d 8. C, NaCl stressed at d 8. x, Xylem; p, phloem; and c, cortex. Bar = 260 μm; all panels are shown at the same magnification.

Table I.

Morphometric analysis of cross-sections from the differentiation zone of the primary root

| Tissue | d 3 | d 8

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Stressed | ||

| Conduction system | |||

| Phloem areaa | 0.035 ± 0.004a | 0.026 ± 0.003b | 0.027 ± 0.004b |

| Xylem areaa | 0.017 ± 0.003a | 0.011 ± 0.001b | 0.015 ± 0.002a |

| Xylem elementsb | 49 ± 1a | 32 ± 1b | 49 ± 7a |

| Cortex | |||

| Intercellular/cellular area | 0.043 ± 0.001a | 0.049 ± 0.002b | 0.038 ± 0.003c |

Cross-sections similar to those shown in Figure 5 were analyzed as indicated in Methods. Data are the means ± sd of at least four seedlings from each group. Values in the same line with different lowercase letters are significantly different (P < 0.05) by the Student's t test.

Area (square millimeters) occupied by the phloem or the xylem in the cross-sections analyzed.

Number of vessels from the protoxylem and the metaxylem in the cross-sections analyzed.

No appreciable effect of the saline stress was observed in the phloem (Fig. 5; Table I). In the cortex the intercellular-to-cellular-area ratio was significantly decreased in the NaCl-stressed roots (Table I), reflecting a reduction in the apoplast in response to the increased NaCl concentration in the growth medium.

Temporal Evolution and Tissue Localization of Peroxidase Activity in Developing Roots

To determine whether the above results reflect a direct effect of saline stress on the seedling growth rate leading to a delayed evolution of every parameter linked to root development, we analyzed the effect of NaCl on a peroxidase involved in lignification (Goldberg et al., 1983). This enzyme activity, measured with the substrate syringaldazine, was not affected in tomato roots under saline conditions (Peyrano et al., 1997).

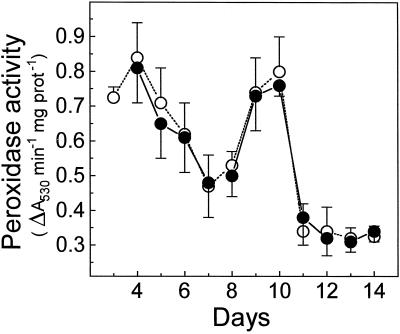

As shown in Figure 6, peroxidase activity in the differentiation zone of control roots presented two maxima: one at d 3 to 4, coincident with the peak of AOX capacity reported by Hilal et al. (1997), and the other at d 9 to 10. The temporal pattern of peroxidase activity was unaffected by the saline conditions.

Figure 6.

Temporal evolution of peroxidase activity in the differentiation zone of control (○) and NaCl-stressed (•) roots. Each value is the mean ± sd of three separate measurements. prot, Protein.

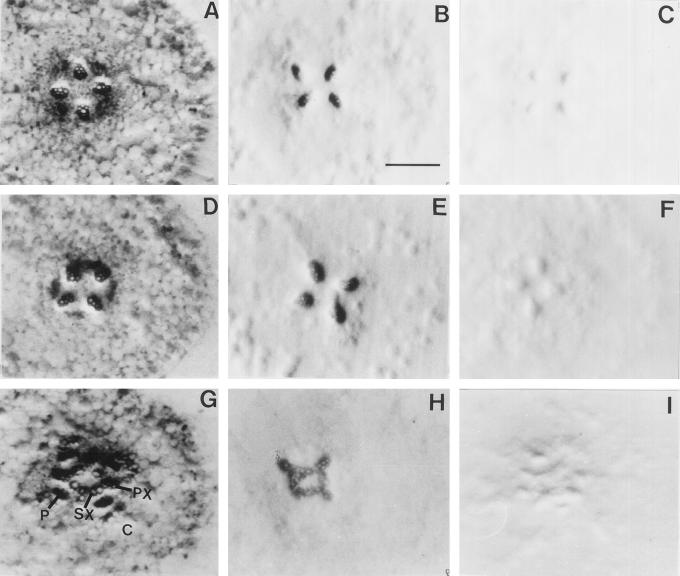

The tissue localization of this peroxidase is shown in Figure 7. The enzyme was concentrated in the xylem at d 3 and 10 (Fig. 7, B, E and H). An unexpected result revealed by tissue prints in Figure 7 was the accelerated development of secondary xylem in the NaCl-stressed roots (Fig. 7, G and H) compared with the control roots (Fig. 7, D and E). The development of the secondary xylem in the control roots was slower and its appearance at d 18 became similar to that of the NaCl-stressed roots at d 10, as evidenced by tissue-print analysis (not shown).

Figure 7.

Localization of peroxidase activity. Tissue prints of cross-sections from the root differentiation zone: at d 3, after germination in sand (A, B, and C); at d 10, controls (D, E, and F); and at d 10, NaCl stressed (G, H, and I). A, D, and G, Toluidine blue stain of total protein. B, E, and H, Stain for peroxidase activity. C, F, and I, Blanks for peroxidase activity, omitting the substrate H2O2. PX, Primary xylem; SX, secondary xylem; P, phloem; and C, cortex. Bar = 350 μm; all panels are shown at the same magnification.

DISCUSSION

The reduction in the apoplast of stressed roots relative to the controls (Table I) is in agreement with previous data on the effects of NaCl in bean roots (Cachorro et al., 1995) and probably reflects an adaptive response to avoid NaCl loading (Wegner and Raschke, 1994). Data in this paper revealed that saline stress alters the temporal pattern of xylem differentiation, leading to the delayed development of the primary xylem (derived from the pro-cambium) and precocious development of the secondary xylem (derived from the cambium). Thus, saline stress had opposite effects on the temporal evolution of primary and secondary xylem, two tissues with different ontogenic processes.

AOX protein, which has a xylem-specific localization (Hilal et al., 1997), exhibited a delayed pattern of expression that was apparently linked to primary xylem development. In this regard, it should be noted that depending on the developmental stage at which exposure to salinity is initiated, three different situations were observed: (a) when NaCl treatment was initiated before the increase in AOX capacity (Fig. 3), there was a shift in the peak and, thus, values either lower or higher than the controls could be obtained at different days of growth; (b) when NaCl treatment was initiated when AOX capacity was high (Fig. 2), there was a delay in the decline of AOX capacity and, thus, values higher than the controls were obtained between d 4 and 12; and (c) when NaCl treatment was initiated after AOX decline (Fig. 2), there was no NaCl-induced enhancement of AOX capacity. Therefore, it is clear that salinity delays developmental processes linked to AOX expression. Once such events have occurred, NaCl is not able to modify AOX capacity.

On the contrary, the temporal evolution of a peroxidase activity localized in the xylem was not affected by saline stress even though this enzyme presented a peak of activity at d 3 to 4 of root development (Fig. 6), coincident with the peak of AOX capacity. Therefore, saline stress does not alter the evolution of every parameter that has a temporal pattern linked to root development or seedling age.

In conclusion, this work is the first demonstration, to our knowledge, of NaCl-induced retardation in primary xylem differentiation associated with a delayed pattern of AOX expression, as well as subsequent acceleration in the secondary xylem differentiation. The net result is that the NaCl-stressed plant is not only smaller than the control one but has specific modifications in various biochemical and morphological parameters.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Thomas E. Elthon (University of Nebraska, Lincoln) for providing the anti-AOX monoclonal antibody and Carolina Schlick (Laboratorio de Microscopía Electrónica del Noroeste, Tucumán, Argentina) for collaborating in sample preparation for light microscopy. Seeds were generously provided by Graciela Salas from the Estación Experimental O. Colombres (Tucumán, Argentina).

Abbreviation:

- AOX

alternative oxidase

Footnotes

This work was partially supported by the Consejo de Investigaciones de la Universidad Nacional de Tucumán and by the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas of Argentina.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bohnert HJ, Jensen RG. Metabolic engineering for increased salt tolerance—the next step. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1996;23:661–667. [Google Scholar]

- Cachorro P, Olmos E, Ortiz A, Cerdá A. Salinity-induced changes in the structure and ultrastructure of bean root cells. Biol Plant. 1995;37:273–283. [Google Scholar]

- Cachorro P, Ortiz A, Cerdá A. Effects of saline stress and calcium on lipid composition in bean roots. Phytochemistry. 1993;32:1131–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman JM. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance in plants. Plant Physiol. 1988;87:547–550. doi: 10.1104/pp.87.3.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day DA, Krab K, Lambers H, Moore AL, Siedow JN, Wagner AM, Wiskich JT. The cyanide-resistant oxidase. To inhibit or not to inhibit, that is the question. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:1–2. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day DA, Whelan J, Millar AH, Siedow JN, Wiskich JT. Regulation of the alternative oxidase in plants and fungi. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1995;22:497–509. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes De Melo D, Jolivet Y, Rocha Facanha A, Gomes Filho E, Silva Lima M, Dizengremel P. Effect of salt stress on mitochondrial energy metabolism of Vigna unguiculata cultivars differing in NaCl tolerance. Plant Physiol. 1994;32:405–412. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg R, Catesson AM, Czaninski Y. Some properties of syringaldazine oxidase, a peroxidase specifically involved in the lignification processes. Z Pflanzenphysiol Bd. 1983;110S:267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Hare PD, du Plessis S, Cress WA, van Staden J. Stress-induced changes in plant gene expression. S Afr J Sci. 1996;92:431–439. [Google Scholar]

- Hilal M, Castagnaro AP, Moreno H, Massa EM. Specific localization of the respiratory alternative oxidase in meristematic and xylematic tissues from developing soybean roots and hypocotyls. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:1499–1503. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.4.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H, Evans ML. Specialized zones of development in roots. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:725–727. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.3.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolivet Y, Pireaux JC, Dizengremel P. Changes in properties of barley leaf mitochondria isolated from NaCl-treated plants. Plant Physiol. 1990;94:641–646. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.2.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar AH, Atkin OK, Lambers H, Wiskich JT, Day DA. A critique of the use of inhibitors to estimate partitioning of electrons between mitochondrial respiratory pathways in plants. Physiol Plant. 1995;95:523–532. [Google Scholar]

- Moore AL, Siedow JN. The regulation and nature of the cyanide-resistant alternative oxidase of plant mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1059:121–140. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(05)80197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns R. Physiological processes limiting plant growth in saline soils: some dogmas and hypotheses. Plant Cell Environ. 1993;16:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Peyrano G, Taleisnik E, Quiroga M, Forchetti SM, Tigier H. Salinity effects on hydraulic conductance, lignin content and peroxidase activity in tomato roots. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1997;35:387–393. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis AC, Shewfelt RL. Does the alternative pathway ameliorate chilling injury in sensitive plant tissues? Physiol Plant. 1993;88:712–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1993.tb01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson K, Jarret L, Finke E. Embedding in epoxy resins for ultra thin sectioning in electron microscopy. Stain Technol. 1960;35:313–315. doi: 10.3109/10520296009114754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siedow JN, Umbach AL. Plant mitochondrial electron transfer and molecular biology. Plant Cell. 1995;7:821–831. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurr AR. A low viscosity epoxy resin embedding medium for electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Res. 1969;26:31–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(69)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surjus A, Durand M. Lipid changes in soybean root membranes in response to salt treatment. J Exp Bot. 1996;47:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner LH, Raschke K. Ion channels in the xylem parenchyma of barley roots. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:799–813. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.3.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenoff AM, Hilal M, Galo M, Moreno H. Changes in root lipid composition and inhibition of the extrusion of protons during salt stress in two genotypes of soybean resistant or susceptible to stress. Varietal differences. Plant Cell Physiol. 1994;35:729–735. [Google Scholar]