Abstract

Neoplastic growth is associated with increased polyamine biosynthetic activity and content. Tumor promoter treatment induces the rate-limiting enzymes in polyamine biosynthesis, ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), and S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (AdoMetDC), and targeted ODC overexpression is sufficient for tumor promotion in initiated mouse skin. We generated a mouse model with doxycycline (Dox)-regulated AdoMetDC expression to determine the impact of this second rate-limiting enzyme on epithelial carcinogenesis. TetO–AdoMetDC (TAMD) transgenic founders were crossed with transgenic mice (K5-tTA) that express the tetracycline-regulated transcriptional activator within basal keratinocytes of the skin. Transgene expression in TAMD/K5-tTA mice was restricted to keratin 5 (K5) target tissues and silenced upon Dox treatment. AdoMetDC activity and its product, decarboxylated AdoMet, both increased approximately 8-fold in the skin. This enabled a redistribution of the polyamines that led to reduced putrescine, increased spermine, and an elevated spermine:spermidine ratio. Given the positive association between polyamine biosynthetic capacity and neoplastic growth, it was somewhat surprising to find that TAMD/K5-tTA mice developed significantly fewer tumors than controls in response to 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene/12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate chemical carcinogenesis. Importantly, tumor counts in TAMD/K5-tTA mice rebounded to nearly equal the levels in the control group upon Dox-mediated transgene silencing at a late stage of tumor promotion, which indicates that latent viable initiated cells remain in AdoMetDC-expressing skin. These results underscore the complexity of polyamine modulation of tumor development and emphasize the critical role of putrescine in tumor promotion. AdoMetDC-expressing mice will enable more refined spatial and temporal manipulation of polyamine biosynthesis during tumorigenesis and in other models of human disease.

Introduction

The diamine putrescine and the polyamines spermidine and spermine are cationic molecules found in all eukaryotic cells (1,2). Polyamine content is tightly regulated through biosynthesis, catabolism, uptake, and efflux mechanisms to maintain optimal levels that are required for cellular events such as DNA replication, gene transcription, messenger RNA (mRNA) translation, and ion channel function (3). Excess polyamine accumulation is linked to neoplastic growth, and the pathway is a promising target for the treatment and prevention of cancer (4,5).

Ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) catalyzes the production of putrescine in the first rate-limiting step of polyamine biosynthesis. Numerous mechanisms regulate the expression and activity of ODC (6) including the regulatory protein antizyme (AZ), which inhibits ODC activity, promotes ODC degradation, and suppresses the uptake of exogenous polyamines (7). ODC levels are extremely low in quiescent cells, increase rapidly and robustly in response to growth promoting stimuli or activated oncogenes, and are constitutively upregulated in neoplastic tissues (8). ODC has received extensive consideration as an enzyme target for chemoprevention (4).

S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (AdoMetDC) is the second rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of polyamines (9). The loss of either decarboxylase gene results in very early embryonic lethality in the mouse (10,11). AdoMetDC catalyzes the formation of decarboxylated S-adenosylmethionine (dcAdoMet) from AdoMet. dcAdoMet serves as an aminopropyl donor in the sequential conversions of putrescine to spermidine and spermidine to spermine, which are catalyzed by the independent aminopropyltransferases spermidine synthase and spermine synthase, respectively. The intracellular level of dcAdoMet is normally very low, and the activities of the constitutively expressed aminopropyltransferases are largely controlled by the availability of this substrate. Thus, AdoMetDC activity determines the rate of conversion of putrescine to higher polyamines, and it is highly regulated at multiple levels including transcription, translation, proenzyme processing, catalytic activity, and degradation (1). AdoMetDC transfection of rodent fibroblasts yields a highly invasive and pro-angiogenic transformed phenotype (12,13), and this enzyme has also been proposed as a target for cancer prevention and therapy (5,14).

The mouse skin chemical carcinogenesis model (15) has been widely utilized to study epithelial tumor development and its modulation by polyamines. In this model, initiation is accomplished by a single application of the mutagen 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA), and macroscopic tumors are detected following tumor promotion with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA). This treatment regimen leads to the clonal expansion of keratinocytes harboring a DMBA-induced activating mutation in codon 61 of c-Ha-ras (Hras1). Many studies have attempted to characterize the critical biochemical events that drive tumor promotion and early efforts identified rapid and dramatic dose-dependent increases in both ODC and AdoMetDC following TPA application. Moreover, ODC and AdoMetDC activities and polyamine content are constitutively elevated in DMBA/TPA-induced tumors as well as human nonmelanoma skin cancer (16–18).

Transgenic mouse models have greatly facilitated studies on the role of polyamine regulatory proteins in normal development as well as disease, with a particular focus on neoplastic growth (19–21). Despite the knowledge that TPA induces both ODC and AdoMetDC, the vast majority of attention has focused on the role of ODC in skin carcinogenesis. Studies in transgenic mouse models with keratin promoter-driven overexpression of key polyamine regulatory proteins in specific skin cell populations found that (i) keratin 5 (K5)-ODC and K6-ODC mice develop tumors in initiated skin without the need for tumor promotion (22,23); (ii) K5-AZ and K6-AZ mice exhibit reduced skin tumor development (24–26); and (iii) treatment with the ODC inhibitor α-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) (25–27) or heterozygous deletion of the Odc gene (28) reduces tumor susceptibility. Taken together, these studies indicate that ODC induction and increased cellular putrescine content are required for skin tumor development (21,29), which provided the rationale to investigate DFMO as a chemopreventive agent for nonmelanoma skin cancer (30).

Thus far, no in vivo studies have addressed whether increased AdoMetDC activity alters epithelial carcinogenesis. Therefore, our goal was to develop a mouse model with tissue specific and regulated AdoMetDC expression in order to evaluate the role of this enzyme in tumor promotion and progression. We found that overexpression of AdoMetDC promotes the synthesis of spermidine and spermine at the expense of putrescine, which somewhat unexpectedly reduces the susceptibility to skin chemical carcinogenesis.

Materials and methods

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO) and Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) unless noted. Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized and purified in the Macromolecular Core Facility (Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine). [35S]-dcAdoMet was synthesized from L-[35S]methionine (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) as described (31). S-adenosyl-L-[carboxyl-14C]-methionine (54–55 mCi/mmol) was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ) and American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO) and L-[1-14C]-ornithine was obtained from PerkinElmer (57.1 mCi/mmol). Anti-HA antibody (sc-805) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Transgene construction and microinjection

The construct for regulated AdoMetDC expression was produced by inserting a human AdoMetDC (AMD1) complementary DNA (cDNA) into the SalI and SpeI sites of the vector pTMILA that contains an internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-firefly luciferase cassette downstream of the Tet operon repeat sequences (Fig. 1A) (32). Human AdoMetDC cDNA was amplified by PCR from plasmid pαMHC-AdoMetDC (33) and was modified to add specific restriction sites and to replace the carboxyl-terminal six residues with a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope with sense primer 5ʹ-GACGCATTAGGTCGACGTTTAATTTAGTTGATTTTCTGTGG-3ʹ (SalI site in italics) and antisense primer 5ʹ-GACGCATTAGACTAGTTCATCAAGCGTAGTCTGGGACGTCGTATGGGTACTTCTTAGCAAAACTGGTAAAAAC-3ʹ (SpeI site in italics and HA epitope-coding sequence underlined). The resulting cDNA is flanked by 53bp of 5ʹ-untranslated region.

Fig. 1.

Transgene construct for regulated AdoMetDC expression. (A) Human AdoMetDC cDNA was modified by PCR to add specific restriction sites and replace the C-terminal six residues with an HA epitope. The modified cDNA was then ligated into a vector containing an IRES-luciferase cassette to generate the TAMD construct. A 5.6-Kb fragment released by Not I digestion was purified and used for microinjection. (B) TAMD mice were bred with K5-tTA mice to generate bitransgenic animals with regulated AdoMetDC expression in the skin. In this system, AdoMetDC and luciferase are translated from the same mRNA in the absence of Dox, and transgene expression is silenced by Dox treatment. (C) Genotyping by PCR with primers P1 and P2 in (A) yielded a 330-bp product only from the tail DNA of transgenic animals (lane 2). Primers that amplify a 520-bp product from the mouse AZ gene (Oaz1) were included in all reactions as a positive control.

A 5.6-Kb transgene fragment released by NotI digestion of the plasmid pTetO–AdoMetDC was used for microinjection. The transgene was purified using the Perfectprep gel cleanup kit (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY) and Elutip-D mini-columns (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) before microinjection into fertilized FVB/NJ oocytes using standard techniques, and transgenic founders were identified by PCR as described in the next section.

Founder line identification and propagation

All animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine. Genomic DNA was isolated from tail biopsies and subjected to PCR analysis using the REDExtract-N-Amp Tissue PCR Kit (Sigma) to detect the transgene DNA. The sense primer (5ʹ-GAGCTCGTTTAGTGAACCGTCAG-3ʹ) binds in the TetO–PCMV enhancer/promoter region and the antisense primer (5ʹ-GTATGTCCCACTCAGATCTTGGG-3ʹ) binds in the human AdoMetDC coding region (Fig. 1A) to amplify a 330-bp product only in genomic DNA samples from mice bearing the transgene. A second primer pair that yields a 520-bp product from the mouse ODC antizyme 1 gene (Oaz1) was also included in the reaction and provides a positive control for successful PCR amplification from each genomic DNA sample (24).

To enable regulated AdoMetDC expression in the skin, TetO–AdoMetDC (TAMD) founders or their progeny were bred to hemizygous K5-tTA mice (FVB/N-Tg(KRT5-tTA)1216Glk (34)) to produce approximately equal numbers of TAMD/K5-tTA, TAMD, K5-tTA, and wild-type littermate controls. All transgenic lines were maintained on an inbred FVB/NJ background (Stock 001800, Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME), and offspring were genotyped for both transgenes by PCR. The K5-tTA transgene was identified with sense (5ʹ-CGCCCAGAAGCTAGGTGTAG-3ʹ) and antisense primers (5ʹ-GCTCCATCGCGATGACTTAG-3ʹ) that hybridize within the tTA coding region and yield a 200-bp product. All experimental groups utilized approximately equal numbers of male and female mice from multiple litters and no sex-dependent differences were observed.

Short-term TPA experiments

An area of caudal dorsal skin (approximately 2.5 × 2.5cm) was shaved at 7–8 weeks of age with surgical clippers, and 6.8 nmol of TPA (Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp., La Jolla, CA) in 200 µl of acetone was applied 16–24h later. For multiple applications of TPA, mice were treated twice weekly for 2 weeks at 3–4-day intervals. Mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation at the indicated time after treatment, and treated skin was separated into epidermal and dermal fractions for biochemical analysis (24) or fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin.

DMBA/TPA skin chemical carcinogenesis

Approximately 40 newborn pups (1 day old) for each genotype were initiated with 200 nmol DMBA (Kodak Laboratory Chemicals, Rochester, NY) in 20 µl acetone applied topically to dorsal skin. Tumor promotion began at 8 weeks of age with twice weekly application of 6.8 nmol TPA in 200 µl acetone. For each genotype, the treatment groups were: (i) 10 mice received DMBA alone and were monitored for 40 weeks for tumor development; (ii) approximately 30 mice received both DMBA and TPA and were monitored for 25 weeks of tumor promotion; and (iii) approximately half of the mice in (ii) were switched to a diet containing 2g/kg doxycycline (Dox; Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ) and tumors were monitored for an additional 10 weeks, while TPA promotion was continued. Tumor volume was calculated as mm3 = length × (width)2 × 0.52.

Skin and tumor sample processing and biochemical assays

For AdoMetDC and ODC activities, tissue extracts were assayed in duplicate as described (24,33). For luciferase activity, 10 µl tissue supernatant processed in AdoMetDC harvesting buffer was diluted in 40 µl passive lysis buffer and assayed in duplicate using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) and a Monolight 2010 luminometer (Analytical Luminescence Laboratory, Ann Arbor, MI). Enzyme activity values were normalized to total protein levels determined using the Bio-Rad dye reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) with BSA standard. Cytosolic proteins were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane for western blotting using anti-HA antibody with the signal visualized by chemiluminescence detection (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). Polyamine (24) and AdoMet/dcAdoMet (31) levels were quantified by HPLC as described and normalized to total protein or tissue wet weight.

Histopathology

An ACVP-diplomate veterinary pathologist evaluated all samples in a blinded manner. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections were scored for hair follicle morphogenesis and hair follicle cycle stages (35,36), and preneoplastic and neoplastic lesions were evaluated according to standard criteria (37,38).

Statistical analysis

For DMBA/TPA carcinogenesis studies, statistical comparisons were performed with Mann–Whitney U-test for tumor multiplicity and log-rank test of the Kaplan–Meier tumor-free survival curves for tumor incidence. The change in tumor multiplicity between before Dox (25 weeks of promotion) and after Dox (35 weeks of promotion) treatment was compared by a two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. All other comparisons utilized the two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test.

Results

Generation of bitransgenic mice with regulated AdoMetDC expression

To evaluate the effects of increased AdoMetDC activity on mouse skin carcinogenesis, we generated mice with targeted and regulated AdoMetDC expression by utilizing the Tet-off system that relies on two independent transgenes. The first transgene (Figure 1A) included a human AdoMetDC (AMD1) cDNA insert with a greatly abbreviated 5ʹ untranslated region to abrogate translational regulation by polyamines (39). The cDNA was also modified to replace the carboxyl-terminal six residues, which are not essential for enzyme processing or activity (9), with an HA epitope to facilitate the detection of transgene-derived AdoMetDC and differentiate it from the endogenous protein.

TAMD transgenic mice were produced and then bred with K5-tTA transgenic mice that express tTA in basal cells of the skin and other stratified epithelia. This system (Figure 1B) allows for spatial and temporal control of transgene expression in bitransgenic TAMD/K5-tTA mice that will be restricted to tissues where the K5 promoter is active and will be silenced upon administration of the tetracycline analog Dox. Genomic DNA screening (Figure 1C) identified eight potential founder mice (designated A to H), but only six founders transmitted the transgene to their offspring upon breeding. As soon as mice began to develop the hair coat, bitransgenic TAMD/K5-tTA mice from two founder lines (A and B) exhibited a thin fur phenotype that was retained throughout their lifespan. When nursing dams were fed Dox-containing chow (2g/kg) from the day of delivery and pups were maintained on this diet after weaning, this thin fur phenotype was not observed through 7 weeks of age (data not shown). For line TAMD(A), bitransgenic mice were produced at a slightly lower frequency than expected [120 of 617 weaned mice (19.4%)], but a complete necropsy of adult animals failed to reveal any pathology or developmental abnormalities.

Characterization of transgene expression in bitransgenic mouse skin

The TAMD construct contains an IRES-luciferase cassette that enables translation of the luciferase reporter protein from the same mRNA transcript as AdoMetDC in bitransgenic mice. Luciferase activity thus serves as a surrogate marker of transgene expression and was utilized to evaluate transgene expression characteristics in the TAMD founder lines. Both in vivo bioluminescence imaging (Supplementary Figure 1A, available at Carcinogenesis Online) and in vitro assays of luciferase activity (Supplementary Table I, available at Carcinogenesis Online) showed that luciferase expression was detected in bitransgenic mice from all six founder lines with the highest levels in line A. When bitransgenic pups from line A were treated with Dox beginning at 1 day old, epidermis and dermis from 8-week-old mice had minimal luciferase activity. Bitransgenic TAMD/K5-tTA mice from founder line A also exhibited robust luciferase activity in additional tissues where the K5 promoter is active (Supplementary Table II, available at Carcinogenesis Online). In contrast, almost no expression was detected in randomly selected non-K5-expressing tissues or in any tissues from single transgenic TAMD mice. Therefore, the model allows for Dox-regulated and tissue-specific AdoMetDC expression in bitransgenic animals.

Based on the luciferase activity results and clear evidence of transgene-derived AdoMetDC protein in dermal extracts (Supplementary Figure 1B, available at Carcinogenesis Online), we focused on lines A and B to specifically quantify AdoMetDC enzymatic activity in the skin of 7-week-old mice (Table I). Bitransgenic mice from line A exhibited a 7.2-fold increase in AdoMetDC activity in epidermis and a 7.8-fold increase in dermis. Mice from line B had lesser increases of 2.7 and 1.8-fold in epidermal and dermal activities, respectively.

Table I.

AdoMetDC activity and AdoMet/dcAdoMet levels in bitransgenic mice

| Genotype | AdoMetDC | AdoMet | dcAdoMet | |

| Epidermis | Dermis | Dermis | Dermis | |

| Wild type | 72±15 | 75±12 | 2.8±0.8 | 0.024±0.008 |

| K5-tTA | 93±33 | 108±60 | 3.9±1.2 | 0.028±0.015 |

| TAMD(A) | 87±24 | 78±3 | 2.6±0.3 | 0.043±0.015 |

| TAMD(A)/K5-tTA | 516±99** | 582±147** | 6.7±1.5** | 0.193±0.079* |

| TAMD(B) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| TAMD(B)/K5-tTA | 192±51** | 138±48* | ND | ND |

Epidermis and dermis were harvested from 7-week-old mice of the indicated genotype and assayed for AdoMetDC activity (pmol CO2/30min/mg protein) and AdoMet and dcAdoMet content (pmol/mg tissue). TAMD founder lines A or B are indicated in parentheses. Values are mean ± standard deviation of 3–8 samples. ND, not determined.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 versus wild-type controls.

AdoMetDC catalyzes the production of the aminopropyl donor dcAdoMet from AdoMet; therefore, the impact of AdoMetDC overexpression on skin AdoMet/dcAdoMet content was measured in dermis of TAMD/K5-tTA mice from line A and controls. As shown in Table I, dermal dcAdoMet levels rose by 8-fold, which is similar to the fold increase (7.8-fold) in AdoMetDC activity. The AdoMet level was also increased by 2.4-fold in the dermis of bitransgenic mice. Mice from TAMD line A were used for all subsequent studies.

TPA-stimulated AdoMetDC and ODC induction in bitransgenic mouse skin

To evaluate the effects of AdoMetDC expression on tumor promoter-stimulated polyamine biosynthesis in the skin, ODC and AdoMetDC activities were measured after a single application of TPA or acetone vehicle. A pilot experiment with wild-type FVB mice indicated the peak AdoMetDC activity occurred 12h after TPA and peak ODC activity was at 4h (data not shown). Skin tissues were isolated at these times after TPA application (6.8 nmol) and assayed for epidermal and dermal enzyme activity (Table II). As expected, basal AdoMetDC activity was highest in TAMD/K5-tTA skin. At 12h after TPA treatment, bitransgenic mice again exhibited the highest levels of AdoMetDC activity even though the fold increase in AdoMetDC activity was greater in the wild type and single transgenic control groups. Therefore, AdoMetDC activity in bitransgenic mouse skin is constitutively elevated within a physiological range that is similar to the level induced transiently by TPA in wild-type mice.

ODC activity in acetone-treated skin was very low in all genotype groups with a modest elevation in K5-tTA and TAMD/K5-tTA epidermis and dermis (Table II). To further investigate this unexpected finding, we conducted histopathological analysis of skin sections taken from these same animals. While nearly all follicles from the wild type and TAMD single transgenic mice were in the resting phase (telogen) or earliest growth phase (anagen I) of the hair cycle, follicles from the K5-tTA and TAMD/K5-tTA mice were primarily in the later stages of anagen (Supplementary Figure 2, available at Carcinogenesis Online). This is likely to account for the increased ODC activity in acetone-treated K5-tTA and TAMD/K5-tTA mice because it is known that anagen hair follicles have elevated ODC activity and polyamine levels (40).

TPA induced a dramatic increase in the epidermal ODC activity in wild type and TAMD single transgenic mice (Table II). Surprisingly, K5-tTA and TAMD/K5-tTA bitransgenic mice exhibited a greater than 70% reduction in epidermal ODC activity relative to wild-type animals. TPA increased dermal ODC activity to a lesser extent relative to epidermis for all groups, and again, K5-tTA and TAMD/K5-tTA mice exhibited reduced ODC activity. The observation of altered hair follicle cycling and impaired TPA induction of ODC in both K5-tTA and TAMD/K5-tTA skin indicates that these effects are related to the K5-tTA transgene rather than increased AdoMetDC expression and activity.

TPA-stimulated proliferation and polyamine accumulation in bitransgenic mouse skin

To determine whether AdoMetDC expression affects tumor promoter-induced proliferation in the basal keratinocyte compartment, skin sections were analyzed for BrdU incorporation after single or multiple TPA (6.8 nmol) applications (Supplementary Table III, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The interfollicular basal cell labeling index at the peak time (17h) after a single application of TPA or 24h after the last of four TPA applications (twice weekly for 2 weeks) was slightly reduced in TAMD/K5-tTA mice although the reduction was not statistically significant. However, epidermal thickness was significantly reduced in both K5-tTA and TAMD/K5-tTA mice. Thus, the skin of K5-tTA and TAMD/K5-tTA mice is hyposensitive to TPA-mediated epidermal thickening.

We also examined whether AdoMetDC transgene expression altered polyamine levels following four TPA applications over a 2-week period with mice analyzed 24h after the last treatment. TAMD/K5-tTA epidermal putrescine levels were reduced (45%), while spermine levels and the spermine:spermidine ratio (45%) was elevated compared with control groups (Supplementary Table IV, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Measurements of polyamine content in untreated skin were extremely variable due to the altered hair follicle cycling in K5-tTA and TAMD/K5-tTA mice.

Hair follicle morphogenesis and skin polyamine content in newborn bitransgenic mice

We analyzed newborn mouse skin in an attempt to identify an age when mice of all four genotypes exhibit similar follicle morphology to better determine the effect of AdoMetDC expression on skin polyamine content. There were no differences in hair follicle morphogenesis stage (Figure 2A) or hair follicle density (Figure 2B) between any of the four genotypes at day 1 of age. Putrescine content was significantly reduced (49%) and the spermine:spermidine ratio was significantly elevated (44%) in TAMD/K5-tTA mice relative to controls (Figure 2C), which is in agreement with the results in 4× TPA-treated skin (Supplementary Table IV, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Therefore, the additional dcAdoMet supplied by transgenic AdoMetDC expression stimulates a shift in polyamine content from putrescine to spermine without substantially increasing total polyamine levels.

Susceptibility of AdoMetDC-expressing mice to skin chemical carcinogenesis

We utilized DMBA/TPA chemical carcinogenesis to determine the impact of increased AdoMetDC activity on susceptibility to skin tumor development. Based on the knowledge that anagen skin is more sensitive to DMBA initiation (15) and our findings that hair follicle stages differed from controls in 7–8 week old but not 1 day old TAMD/K5-tTA skin, we chose to initiate 1-day-old mice with DMBA (200 nmol). The genetic alterations induced by DMBA are irreversible, and TPA promotion (6.8 nmol) began at 8 weeks of age.

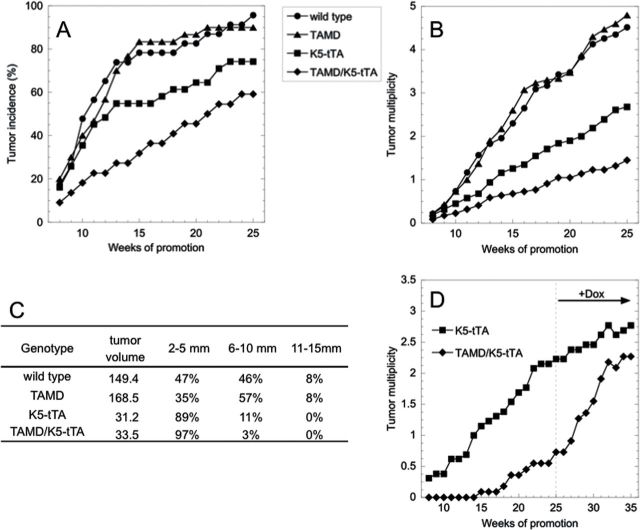

The wild type and TAMD single transgenic mice exhibited nearly identical tumor responses in all measured parameters. However, TAMD/K5-tTA and K5-tTA mice both developed significantly fewer tumors per animal than wild-type mice (Figure 3A and 3B). An independent group also reported reduced tumor susceptibility in K5-tTA mice during the course of our experiment (41). Therefore, K5-tTA mice represent the proper control group to determine the effects of AdoMetDC on skin tumor susceptibility in TAMD/K5-tTA mice. The average tumor multiplicity was 46% lower in TAMD/K5-tTA relative to K5-tTA mice and tumor incidence was also reduced. Tumors from TAMD/K5-tTA and K5-tTA mice were much smaller than those from wild type and TAMD controls but not statistically different from each other (Figure 3C). There was a low rate of progression to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) after 25 weeks of tumor promotion, with one to two total SCCs identified by gross appearance and confirmed histopathologically in each of the four groups. An additional one to two total SCCs per group were identified by histopathological analysis of randomly selected tumors (n = 10–12 tumors scored per group), and the rest were classified as papillomas.

Fig. 3.

Tumor development in DMBA/TPA-treated TAMD/K5-tTA mice. Mice were initiated at 1 day of age with DMBA (200 nmol) and promoted twice weekly with TPA (6.8 nmol) beginning 8 weeks later and continuing for 25 weeks. (A) Tumor incidence is presented as the percentage of mice in each group containing at least one tumor. Group sizes were wild type, n = 23; TAMD, n = 30; K5-tTA, n = 31; and TAMD/K5-tTA, n = 22. TAMD/K5-tTA versus wild type, P = 0.001; TAMD/K5-tTA versus K5-tTA, P = 0.06. (B) Tumors 2mm and larger were counted weekly and multiplicity is presented as the mean for each genotype. Error bars are not included in order to improve the clarity of the graph, and group sizes are the same as in (A). TAMD/K5-tTA versus wild type and K5-tTA, P < 0.0001. (C) Tumor volume (mm3) was calculated and size range (mm in maximum dimension) was classified for all tumors after 25 weeks of tumor promotion. Total tumor counts were wild type, n = 105; TAMD, n = 151; K5-tTA, n = 75; and TAMD/K5-tTA, n = 31. (D) Following 25 weeks of tumor promotion, a cohort of the mice was switched to Dox-containing diet (2g/kg) to silence transgene expression, and tumor counts (group average) were monitored for an additional 10 weeks, while TPA promotion was continued. K5-tTA, n = 13 and TAMD/K5-tTA, n = 11.

In contrast, TAMD/K5-tTA mice and all three control genotypes (n = 10/group) treated with a single dose of DMBA (200 nmol) alone did not develop any tumors through 40 weeks of observation. Therefore, unlike ODC (22,23), elevated AdoMetDC activity is not a sufficient stimulus to drive tumor promotion in initiated skin. Instead, AdoMetDC overexpression unexpectedly suppressed skin tumor promotion.

We then sought to conclusively demonstrate that the increased AdoMetDC activity is responsible for the reduced tumor susceptibility and to determine the reversibility of this phenotype. After 25 weeks of promotion, TAMD/K5-tTA mice were transferred to Dox-containing chow to silence transgene expression, and luciferase activity was reduced over 500-fold in skin and tumor tissue from Dox-treated TAMD/K5-tTA mice (data not shown). TPA promotion was continued, and tumor number was monitored for an additional 10 weeks to detect the emergence of latent initiated cells as macroscopic papillomas (Figure 3D). Tumor counts in Dox-treated TAMD/K5-tTA mice increased by 213% (P < 0.005) to nearly equal the tumor multiplicity in the K5-tTA control group, which increased by only 24% (P = 0.252). Tumor multiplicity in wild type and TAMD groups increased similarly (26% and 28%, respectively).

Luciferase, AdoMetDC, and ODC activities in skin and tumors

Mice were sacrificed 1 week following 25 weeks of tumor promotion to measure luciferase, AdoMetDC, and ODC activities in skin and tumor extracts (Table III). TAMD/K5-tTA mice exhibited robust luciferase activity in the skin that was further elevated in tumor tissue. AdoMetDC was elevated in tumors relative to skin for mice of all genotypes, and skin and tumors from TAMD/K5-tTA mice showed significantly higher AdoMetDC activity than controls. ODC activity was highly increased in tumors relative to adjacent skin for mice of all genotypes. There were no statistically significant differences between tumor polyamine levels of TAMD/K5-tTA mice and controls (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that TAMD/K5-tTA mice exhibit reduced tumor susceptibility and the tumors that these animals develop maintain transgene expression.

Table III.

Enzyme activity in skin and tumors of DMBA/TPA-treated bitransgenic mice

| Genotype | Tissue | Enzyme activity | ||

| Luciferase | AdoMetDC | ODC | ||

| Wild type | Skin | ND | 170±26 | 4.6±1.2 |

| Tumor | ND | 459±225 | 34.5±18.0 | |

| TAMD | Skin | ND | 190±49 | 4.8±1.8 |

| Tumor | ND | 577±169 | 40.1±13.2 | |

| K5-tTA | Skin | ND | 151±57 | 4.3±0.7 |

| Tumor | ND | 672±148 | 38.1±20.3 | |

| TAMD/K5-tTA | Skin | 201±50 | 234±31* | 5.1±1.0 |

| Tumor | 482±131 | 885±169** | 56.7±25.3 | |

Whole skin and tumors were isolated from DMBA/TPA-treated animals (Fig. 3) 1 week after the completion of 25 weeks of TPA application and assayed for luciferase (RLU/10 s/mg protein, mean ± standard error of mean, n = 8), AdoMetDC, and ODC activity (pmol CO2/30min/mg protein, mean ± SD, n = 4 to 5). ND, not determined.

*P < 0.05 versus wild type and K5-tTA,**P < 0.05 versus wild type.

Fig.2.

Hair follicle analysis and polyamine content in newborn TAMD/K5-tTA mice. (A) The hair follicle morphogenesis stage was determined in skin sections harvested from newborn mice (1 day old). Complete longitudinal follicles (n = 60) were scored for 3–7 mice per genotype. (B) Hair follicle density was determined in the same sections as in (A). The average number of follicles connected to the interfollicular epidermis was determined in eight high-power fields for 3–7 mice per genotype. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation (SD). (C) Polyamine levels (left y-axis) and the spermine:spermidine ratio (right y-axis) were determined in whole skin samples harvested from the dorsal surface of newborn mice (1 day old). Bars represent mean ± SD, n = 3 to 5. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 versus wild type; ***P < 0.05 versus K5-tTA.

Discussion

Carcinogenesis studies in mouse models with genetically modulated polyamine metabolism clearly confirmed the prediction that enhanced polyamine biosynthesis contributes to tumor promotion (21,29). However, overexpression of spermidine/spermine-N 1-acetyltransferase (SSAT), which catalyzes the rate-limiting step that boosts polyamine excretion and catabolism via N 1-acetylpolyamine oxidase, paradoxically enhanced tumor promotion and progression in mouse skin and intestine (42,43). Thus, it was clear that the functional contribution of polyamine metabolizing enzymes was not easily predicted and the lack of AdeMetDC-expressing models was an obvious knowledge gap. Therefore, we generated the first transgenic mouse model with regulated AdoMetDC expression to enable tissue-specific and stage-selective expression of this enzyme in order to evaluate its role in epithelial carcinogenesis.

Our studies and others (41) have demonstrated that K5-tTA mice exhibit alterations in hair follicle cycling, which impacts measurements of polyamine biosynthetic activity and content, along with reduced sensitivity to TPA-induced hyperproliferation and resistance to DMBA/TPA carcinogenesis that is not reversed upon Dox treatment. Likely mechanisms to explain these results are genomic alterations induced by transgene integration or tTA protein interaction with endogenous transcription factors or other proteins. The lack of widespread reports of tTA or rTA effects on tumor susceptibility in the numerous other transgenic models that have utilized these proteins supports the former, and the strong impact on tumor susceptibility argues that further characterization of the transgene integration site is warranted. This knowledge mandates that care must be taken in the initiation stage of chemical carcinogenesis and that AdoMetDC-mediated effects must be defined based on comparisons of TAMD/K5-tTA mice to the K5-tTA or Dox-treated TAMD/K5-tTA groups rather than wild-type animals. Using this approach, we clearly demonstrated that tissue-specific AdoMetDC overexpression leads to increased dcAdoMet content, a shift in polyamine profile from putrescine to spermine and a reversible inhibition of tumor promotion.

Hair follicle density and morphogenesis stage was uniform in 1-day-old mice of all genotypes, and TAMD/K5-tTA mice specifically exhibited reduced putrescine content and an increase in the spermine:spermidine ratio. A similar shift in the polyamine profile was observed in adult skin following multiple TPA applications. Many previous studies clearly demonstrate that dcAdoMet availability limits spermine synthesis in vivo (44); therefore, AdoMetDC overexpression facilitates the conversion of putrescine to spermine by providing more of the dcAdoMet substrate that typically limits the activity of the aminopropyltransferases. This raises the question of whether the resistance to tumor development is mediated by reduced putrescine or increased spermine and spermine:spermidine ratios. The latter is very unlikely based on our recent demonstration that mice with constitutive high-level overexpression of spermine synthase, with a resulting increase in spermine and spermine:spermidine ratio, do not exhibit any change in DMBA/TPA susceptibility (44). Conversely, an extensive body of evidence acquired through treatment with DFMO, increased AZ expression and reduction in Odc copy number supports the concept that tumor promotion is impaired by restricted putrescine accumulation in the skin (21,29) as well as other tissues (45–47).

An alternative hypothesis for the reduced tumor appearance in the presence of elevated AdoMetDC activity is that increased spermine levels could lead to feedback stimulation of SSAT expression and activity via numerous well-characterized mechanisms (48). Elevated SSAT activity is known to suppress prostate carcinogenesis and induce flux through the polyamine pathway (49,50). Thus, SSAT induction could set up a futile cycle that consumes critical precursor molecules, notably adenosine triphosphate and acetyl-CoA, thereby resulting in cellular energy depletion and reduced capacity for neoplastic growth. Increased (30 to several hundred-fold) tissue levels of the SSAT product N 1-acetylspermidine (N 1-AcSpd) are a hallmark of mouse models with SSAT overproduction (51). However, very low levels N 1-AcSpd were detected in tumors from TAMD/K5-tTA mice (3.8±1.6% of the spermidine content), and these levels were equivalent to those found in wild-type mice (3.5±0.5%) as well as Dox-treated TAMD/K5-tTA animals (3.8±1.3%). N 1-AcSpd was not detected in newborn skin or TPA-treated adult skin taken from mice of any genotype. These results, together with previous studies clearly demonstrating that targeted SSAT expression actually enhances susceptibility and progression in the DMBA/TPA carcinogenesis model (42,52), argue against SSAT-mediated energy depletion as the mechanism whereby increased AdoMetDC activity suppresses tumor development in TAMD/K5-tTA animals.

Another alternative hypothesis to explain the tumor resistance phenotype includes altered DNA methylation patterns and gene expression. Cellular dcAdoMet is committed to polyamine biosynthesis and its content is typically <5% of AdoMet. With extensive spermidine and spermine depletion following long-term DFMO treatment of cultured cells, AdoMetDC activity is dramatically induced and levels of dcAdoMet can exceed AdoMet (53). Importantly, AdoMet is the methyl donor for numerous reactions including those catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases, and high levels of dcAdoMet can act as a competitive inhibitor to alter methylation of newly replicated DNA and subsequently gene expression. The absence of a massive increase in dcAdoMet content or depletion of AdoMet within the skin of TAMD/K5-tTA mice argues against this hypothesis, but it is worthy of further consideration in future studies.

Interestingly, upon silencing of AdoMetDC expression, latent initiated cells developed into macroscopic tumors. We conclude that elevated AdoMetDC activity in TAMD/K5-tTA mice leads to reduced tumor multiplicity because initiated cells are blocked from developing into macroscopic tumors during the tumor promotion stage. These cells persist in a viable state in the skin and are capable of further growth upon removal of the transgene-derived AdoMetDC. Therefore, putrescine restriction via AdoMetDC overexpression does not irreversibly eliminate initiated cells, which is analogous to previous reports of skin tumor reappearance following cessation of DFMO treatment (54). It is unlikely that AdoMetDC expression affects the initiation stage by altering DMBA metabolism or its interaction with DNA, or that TAMD/K5-tTA mice harbor fewer initiated cells or targetable stem cells because tumor counts rebound to nearly equal those in the K5-tTA control group upon AdoMetDC silencing with Dox. This issue could be further studied in our model by treating with Dox prior to DMBA.

The discovery of reduced tumor susceptibility following AdoMetDC-mediated enhancement of polyamine biosynthetic capacity was somewhat surprising. The overexpression of ODC, the other rate-limiting decarboxylase in polyamine biosynthesis, is sufficient to promote Ras or UV-initiated keratinocytes (29). Elevated AdoMetDC activity has been associated with proliferative stimuli and AdoMetDC transfection of rodent fibroblasts results in a highly invasive, pro-angiogenic transformed phenotype (12,13). These seemingly conflicting concepts can be reconciled by considering the context of each of the experiments. It is likely that additional genetic or epigenetic alterations can profoundly affect the phenotype associated with AdoMetDC overexpression. Our studies involved increasing AdoMetDC activity within the physiological range in the absence of extensive genetic instability as opposed to supraphysiological expression in tumor or nontransformed cell lines selected for viability in culture. The concurrent levels of ODC activity or polyamine uptake activity are likely to be extremely important in determining the ability of AdoMetDC to deplete putrescine and suppress tumor growth. Therefore, the biological effects of AdoMetDC may differ in an initiated cell compared with a tumor that exhibits constitutive ODC induction, and it will be interesting to evaluate the effects of de novo AdoMetDC induction in tumors of a more advanced stage. Finally, a previous study demonstrated that an AdoMetDC inhibitor suppresses DNA and protein synthesis in the skin (55) and the enzyme has been targeted in cancer clinical trials (5,14). Our results do not conflict with the premise that AdoMetDC inhibitors would also exhibit antitumor effects because spermidine is clearly essential for cell growth (1).

AdoMetDC-expressing mice also exhibited a thin fur phenotype that was reversible upon Dox administration. Interestingly, a new mouse model that utilizes the same approach to achieve regulated AZ expression in the skin exhibits a very similar phenotype (D.J.Feith, in preparation). These results are not unexpected because previous studies demonstrate that DFMO treatment suppresses hair growth in both mice and humans, and other mouse models demonstrate extreme hair loss upon ODC or SSAT overexpression (40). The effects of elevated AdoMetDC activity or increased AZ expression on hair follicle morphogenesis, structure, and cycling will be further characterized and reported elsewhere.

In summary, our new mouse model with regulated AdoMetDC expression led to the novel in vivo finding that increased AdoMetDC activity impairs skin tumor promotion. This versatile model will facilitate more sophisticated temporal and spatial manipulation of cellular polyamine content in the mouse. Our studies may also have general implications for human disease. First, it is tempting to propose that modest inherent differences in AdoMetDC activity within the human population impact individual susceptibility to some tumor types as previously characterized for ODC (6). Second, the development of AdoMetDC inhibitors continues, but their clinical niche has yet to be determined. Preclinical analyses demonstrate profound increases in putrescine content in response to these agents, and transfection of an antisense AdoMetDC construct actually transforms rodent fibroblasts (13). Our studies predict that AdoMetDC inhibitors could enhance putrescine-mediated tumor promotion of latent initiated cells, such as sun-damaged keratinocytes, which clearly supports the utilization of AdoMetDC inhibitors in combination with DFMO in order to mitigate this risk.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material

Supplementary Tables I–IV and Figures 1 and 2 can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournal.org/.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (CA018138 to D.F.).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Anthony Pegg for helpful discussions, Dr. Lewis Chodosh (University of Pennsylvania) for providing the pTMILA plasmid, Fan He for statistical analysis of the chemical carcinogenesis data, and Patricia Welsh, Chethana Prakashagowda, Suzanne Sass-Kuhn, and Kerry Keefer for excellent technical support. The authors wish to thank Tom Salada of the Penn State University Transgenic Mouse Facility for microinjection of the TAMD construct, the technicians of the Penn State University College of Medicine Department of Comparative Medicine for expert animal care, and the Penn State University College of Medicine Macromolecular Synthesis and DNA Sequencing Cores.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- PVDF

polyvinylidene difluoride;

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

References

- 1.Pegg A.E. Mammalian polyamine metabolism and function. IUBMB Life. (2009);61:880–894. doi: 10.1002/iub.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace H.M., et al. A perspective of polyamine metabolism. Biochem. J. (2003);376:1–14. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Igarashi K., et al. Modulation of cellular function by polyamines. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. (2010);42:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basuroy U.K., et al. Emerging concepts in targeting the polyamine metabolic pathway in epithelial cancer chemoprevention and chemotherapy. J. Biochem. (2006);139:27–33. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casero R.A., Jr, et al. Targeting polyamine metabolism and function in cancer and other hyperproliferative diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. (2007);6:373–390. doi: 10.1038/nrd2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pegg A.E. Regulation of ornithine decarboxylase. J. Biol. Chem. (2006);281:14529–14532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahana C. Regulation of cellular polyamine levels and cellular proliferation by antizyme and antizyme inhibitor. Essays Biochem. (2009);46:47–61. doi: 10.1042/bse0460004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shantz L.M., et al. Regulation of ornithine decarboxylase during oncogenic transformation: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Amino Acids. (2007);33:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0531-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pegg A.E. S-Adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. Essays Biochem. (2009);46:25–45. doi: 10.1042/bse0460003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pendeville H., et al. The ornithine decarboxylase gene is essential for cell survival during early murine development. Mol. Cell. Biol. (2001);21:6549–6558. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.19.6549-6558.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishimura K., et al. Essential role of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase in mouse embryonic development. Genes Cells. (2002);7:41–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1356-9597.2001.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paasinen-Sohns A., et al. Chaotic neovascularization induced by aggressive fibrosarcoma cells overexpressing S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. (2011);43:441–454. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paasinen-Sohns A., et al. c-Jun activation-dependent tumorigenic transformation induced paradoxically by overexpression or block of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. J. Cell Biol. (2000);151:801–810. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.4.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seiler N. Thirty years of polyamine-related approaches to cancer therapy. Retrospect and prospect. Part 1. Selective enzyme inhibitors. Curr. Drug Targets. (2003);4:537–564. doi: 10.2174/1389450033490885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abel E.L., et al. Multi-stage chemical carcinogenesis in mouse skin: fundamentals and applications. Nat. Protoc. (2009);4:1350–1362. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Brien T.G. The induction of ornithine decarboxylase as an early, possibly obligatory, event in mouse skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. (1976);36:2644–2653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koza R.A., et al. Constitutively elevated levels of ornithine and polyamines in mouse epidermal papillomas. Carcinogenesis. (1991);12:1619–1625. doi: 10.1093/carcin/12.9.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scalabrino G., et al. Degree of enhancement of polyamine biosynthetic decarboxylase activities in human tumors: a useful new index of degree of malignancy. Cancer Detect. Prev. (1985);8:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feith D.J. Carcinogenesis studies in mice with genetically engineered alterations in polyamine metabolism. Methods Mol. Biol. (2011);720:129–141. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-034-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jänne J., et al. Genetic approaches to the cellular functions of polyamines in mammals. Eur. J. Biochem. (2004);271:877–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pegg A.E., et al. Polyamines and neoplastic growth. Biochem. Soc. Trans. (2007);35:295–299. doi: 10.1042/BST0350295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien T.G., et al. Ornithine decarboxylase overexpression is a sufficient condition for tumor promotion in mouse skin. Cancer Res. (1997);57:2630–2637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith M.K., et al. Co-operation between follicular ornithine decarboxylase and v-Ha-ras induces spontaneous papillomas and malignant conversion in transgenic skin. Carcinogenesis. (1998);19:1409–1415. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.8.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feith D.J., et al. Mouse skin chemical carcinogenesis is inhibited by antizyme in promotion-sensitive and promotion-resistant genetic backgrounds. Mol. Carcinog. (2007);46:453–465. doi: 10.1002/mc.20294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feith D.J., et al. Tumor suppressor activity of ODC antizyme in MEK-driven skin tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. (2006);27:1090–1098. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang X., et al. Ornithine decarboxylase is a target for chemoprevention of basal and squamous cell carcinomas in Ptch1+/- mice. J. Clin. Invest. (2004);113:867–875. doi: 10.1172/JCI20732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takigawa M., et al. Polyamine biosynthesis and skin tumor promotion: inhibition of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-promoted mouse skin tumor formation by the irreversible inhibitor of ornithine decarboxylase alpha-difluoromethylornithine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. (1982);105:969–976. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Y., et al. Haploinsufficiency for odc modifies mouse skin tumor susceptibility. Cancer Res. (2005);65:1146–1149. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilmour S.K. Polyamines and nonmelanoma skin cancer. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. (2007);224:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailey H.H., et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 skin cancer prevention study of {alpha}-difluoromethylornithine in subjects with previous history of skin cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila). (2010);3:35–47. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pegg A.E., et al. Spermine synthase activity affects the content of decarboxylated S-adenosylmethionine. Biochem. J. (2011);433:139–144. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gunther E.J., et al. Impact of p53 loss on reversal and recurrence of conditional Wnt-induced tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. (2003);17:488–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.1051603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nisenberg O., et al. Overproduction of cardiac S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase in transgenic mice. Biochem. J. (2006);393:295–302. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diamond I., et al. Conditional gene expression in the epidermis of transgenic mice using the tetracycline-regulated transactivators tTA and rTA linked to the keratin 5 promoter. J. Invest. Dermatol. (2000);115:788–794. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hardy M.H. The secret life of the hair follicle. Trends Genet. (1992);8:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90350-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Müller-Röver S., et al. A comprehensive guide for the accurate classification of murine hair follicles in distinct hair cycle stages. J. Invest. Dermatol. (2001);117:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Evans M.G., et al. (1997). Proliferative lesions of the skin and adnexa in rats. In Guides for Toxicologic Pathology Washington, DC: In: Guides for Toxicologic Pathology, STP/ARP/AFIP, Washington, DC, 1-14 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maronpot R.R., et al. (eds) (1999). Pathology of the Mouse: Reference and Atlas Cache River Press; Vienna, IL: [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shantz L.M., et al. Translational regulation of ornithine decarboxylase and other enzymes of the polyamine pathway. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. (1999);31:107–122. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramot Y., et al. Polyamines and hair: a couple in search of perfection. Exp. Dermatol. (2010);19:784–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rozenberg J., et al. Inhibition of CREB function in mouse epidermis reduces papilloma formation. Mol. Cancer Res. (2009);7:654–664. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coleman C.S., et al. Targeted expression of spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase increases susceptibility to chemically induced skin carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. (2002);23:359–364. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tucker J.M., et al. Potent modulation of intestinal tumorigenesis in Apcmin/+ mice by the polyamine catabolic enzyme spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase. Cancer Res. (2005);65:5390–5398. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Welsh P., et al. (2012). Spermine synthase overexpression in vivo does not increase susceptibility to DMBA/TPA skin carcinogenesis or Min-Apc intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Biol. Ther. 13, 358–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Meyskens F.L., Jr, et al. (2008). Difluoromethylornithine plus sulindac for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas: a randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila). 1,32 38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nilsson J.A., et al. Targeting ornithine decarboxylase in Myc-induced lymphomagenesis prevents tumor formation. Cancer Cell. (2005);7:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rounbehler R.J., et al. Targeting ornithine decarboxylase impairs development of MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. (2009);69:547–553. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pegg A.E. Spermidine/spermine-N(1)-acetyltransferase: a key metabolic regulator. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. (2008);294:E995–1010. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90217.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kee K., et al. Activated polyamine catabolism depletes acetyl-CoA pools and suppresses prostate tumor growth in TRAMP mice. J. Biol. Chem. (2004);279:40076–40083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kramer D.L., et al. Polyamine acetylation modulates polyamine metabolic flux, a prelude to broader metabolic consequences. J. Biol. Chem. (2008);283:4241–4251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706806200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jänne J., et al. Genetic manipulation of polyamine catabolism in rodents. J. Biochem. (2006);139:155–160. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang X., et al. Studies of the mechanism by which increased spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase activity increases susceptibility to skin carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. (2007);28:2404–2411. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frostesjö L., et al. Interference with DNA methyltransferase activity and genome methylation during F9 teratocarcinoma stem cell differentiation induced by polyamine depletion. J. Biol. Chem. (1997);272:4359–4366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fischer S.M., et al. Celecoxib and difluoromethylornithine in combination have strong therapeutic activity against UV-induced skin tumors in mice. Carcinogenesis. (2003);24:945–952. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Käpyaho K., et al. Inhibition of DNA and protein synthesis in UV-irradiated mouse skin by 2-difluoromethylornithine, methylglyoxal bis(guanylhydrazone), and their combination. J. Invest. Dermatol. (1983);81:102–106. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12542177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.