Abstract

Every year thousands of people in the USA are diagnosed with small intestine and colorectal cancers (CRC). Although environmental factors affect disease etiology, uncovering underlying genetic factors is imperative for risk assessment and developing preventative therapies. Familial adenomatous polyposis is a heritable genetic disorder in which individuals carry germ-line mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene that predisposes them to CRC. The Apc Min mouse model carries a point mutation in the Apc gene and develops polyps along the intestinal tract. Inbred strain background influences polyp phenotypes in Apc Min mice. Several Modifier of Min (Mom) loci that alter tumor phenotypes associated with the Apc Min mutation have been identified to date. We screened BXH recombinant inbred (RI) strains by crossing BXH RI females with C57BL/6J (B6) Apc Min males and quantitating tumor phenotypes in backcross progeny. We found that the BXH14 RI strain harbors five modifier loci that decrease polyp multiplicity. Furthermore, we show that resistance is determined by varying combinations of these modifier loci. Gene interaction network analysis shows that there are multiple networks with proven gene–gene interactions, which contain genes from all five modifier loci. We discuss the implications of this result for studies that define susceptibility loci, namely that multiple networks may be acting concurrently to alter tumor phenotypes. Thus, the significance of this work resides not only with the modifier loci we identified but also with the combinations of loci needed to get maximal protection against polyposis and the impact of this finding on human disease studies.

Abbreviations:

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

- GWAS

genome-wide association studies

- QTL

quantitative trait loci

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most deadly cancer among men and women in the USA (www.cancer.org). Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal dominant genetic disease characterized by the development of hundreds to thousands of adenomas in the colon beginning in the second decade of life (1). Patients affected by FAP carry a mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene (2,3). These individuals have an ~100% chance of developing CRC by the age of 40 years (4–6).

Mouse models have proven to be powerful tools in the study of intestinal and CRCs. Several mouse models of FAP have been generated over the past two decades (www.informatics.jax.org). The Apc Min model was generated through an ethylnitrosourea mutagenesis screen (7). The Apc Min allele has a T-to-A transversion that creates a premature stop at codon 850 (8). Mice that carry the Apc Min/+ mutation on the C57BL/6J (B6) background develop 50 or more polyps along the length of the intestinal tract (9). B6 Apc Min mice are moribund by 150 days of age due to severe anemia and polyp-induced intestinal blockage (10).

Inbred strain background is known to influence the Apc Min phenotype. Hybrid progeny from a cross between B6 Apc Min/+ mice and AKR/J (AKR), C3H/HeJ (C3H), MA/MyJ, 129P2, or Mus musculus castaneus (CAST/EiJ) mice show a dramatic decrease in polyp number as well as an increase in lifespan (10–15). Conversely, when the Apc Min mutation is carried on the BTBR genetic background, mice develop >600 intestinal polyps and become moribund by 60 days of age (16). The reason for these differences in the Apc Min phenotype between inbred strains has been attributed to modifier genes (11). Several modifier loci of the Apc Min mutation have already been identified (17–19). In particular, the Modifier of Min 1 (Mom1), located on chromosome (Chr) 4, lowers polyp number and size in Apc Min mice (11,12,20). The secretory type II non-pancreatic phospholipase A2 (Pla2g2a) gene is responsible for most of the Mom1 phenotype (21–23).

Previously, we showed that the C3H inbred strain harbors modifier loci of the Apc Min mutation (14). Even without the presence of a resistant Mom1 R allele, offspring from a cross of congenic C3H.B6 Mom1 S/S females to B6 Apc Min/+ mice exhibited significantly fewer polyps than B6 Apc Min/+ controls (14). To further investigate the modifier loci present in the C3H genome, we chose to evaluate the BXH recombinant inbred (RI) strains, whose progenitors are B6 and C3H (24). RI strains are established by crossing two independent inbred strains followed by sequential brother-sister mating for 20 generations starting at the F2 generation (24). Each strain of an RI series has inherited a unique homozygous set of progenitor alleles, with an average of 50% of their genome contributed from one parental strain and 50% of their genome contributed from the other parental strain. Homozygous clustering, in addition to allelic variation, present in RI strains makes them useful tools for mapping complex traits (25). Advantages to using RI strains as opposed to common inbred strains include (i) identification of problems arising from linkage disequilibrium within existing sets, (ii) large RI sets can provide greater statistical power and precision for finer resolution mapping of complex trait loci, and (iii) large RI sets can be utilized for dissecting factors that influence susceptibility, predisposition, penetrance, and expressivity of complex traits (25–27).

Recombinant congenic (RC) strains are also powerful resources in the search for multiple genes involved in quantitative traits (28–30). RC strains are constructed in a similar way to RI strains, starting with a cross between two parental inbred strains (31). Offspring are then selected randomly and backcrossed to one of the parental strains for the next two generations. From this point on, brother-sister mating proceeds for at least 14 generations, creating mice that carry an average of 87.5% of their genome from the recipient progenitor strain and 12.5% of their genome from the donor progenitor strain.

The unique RI and RC strains of the BXH series allow for the identification of modifier loci that were inherited from either the B6 or C3H progenitor strains. To eliminate the protective effect of the resistant Mom1 R locus (present in the progenitor C3H strain), we selected only BXH RI and RC strains that were homozygous for the same susceptible Mom1 S locus carried by the progenitor B6 strain. The range of polyp numbers observed in the RI and RC strains extended from the high to the low parental control groups. To our knowledge, this is the first time that a set of RI strains have been evaluated for their impact on the Apc Min phenotype. In this study, we report the identification of five modifier loci (named Mom14, Mom15, Mom16, Mom17 and Mom18) that lower polyp multiplicity in the small intestine and colon.

Materials and methods

Mice

The BXH2/TyJ, BXH4/TyJ, BXH8/TyJ, BXH14/TyJ, BXH22/KccJ, and B6cC3-1/KccJ mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The BXH22 RI line, the B6cC3-1 RC line, and the C3H.B6 Mom1 S/S congenic line were generated by the Siracusa laboratory at the Kimmel Cancer Center (KCC) (14). The B6cC3-1 RC strain was derived from an initial intercross between the albino B6 Tyr c-2J / Tyr c-2J and the C3H progenitor strains. F1 progeny were backcrossed once to the B6 strain prior to intercrossing for 20 generations. All F20+ mice are considered homozygous and contain ~75% of their alleles from B6 and ~25% of their alleles from C3H. We donated BXH22 and B6cC3-1 to The Jackson Laboratory (http://jaxmice.jax.org).

The TJU Animal Facility provides a specific pathogen-free environment and is accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). Mice were housed in polycarbonate cages from Allentown Caging Equipment Co. (Allentown, NJ). Cages were lined with alpha dry bedding from Shepherd Specialty Papers Inc (Kalamazoo, MI). Mice were fed Laboratory Autoclavable Rodent Diet 5010 from Animal Specialties and Provisions (ASAP) (Quakertown, PA). Food, cages, bedding, and filtered water were autoclaved before use. All protocols were approved by the TJU IACUC committee.

Mating protocol

F1 offspring were produced by crossing BXH# RI females to B6 Apc Min/+ males. Offspring were genotyped for the Apc Min mutation (see DNA isolation and genotyping). Of the offspring produced from this mating, Apc +/+ females were mated to B6 Apc Min/+ males, creating the N2 generation (Supplementary Figure 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Offspring that carried Apc Min were subsequently analyzed for polyp number, size, and location along the intestinal tract. This backcross protocol was repeated to produce successive N# generations.

DNA isolation and genotyping

At weaning, tail biopsies of ~0.5cm were placed in 1.5ml Eppendorf tubes and stored in ice for DNA isolation. Each mouse was ear-notched for identification. DNeasy (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) isolation kits were used to extract genomic DNA from tail tissue according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Mice were genotyped for Apc Min by PCR analysis as described (32).

Polyp counting procedure

Apc Min/+ mice were aged for 110–130 days, then sacrificed via CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation. The intestinal tract was removed and cut longitudinally. The small intestine was divided into proximal (psi), middle (msi), and distal (dsi) sections. The colon was divided into proximal (pc) and distal (dc) sections. Each section was washed with 1× Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.0) to eliminate intestinal contents. A Nikon SMZ-U dissecting microscope (×15 magnification) was used to visualize polyps. For each section of the intestine, the number, size, and location were recorded as described (13,14,33). Polyp size was measured using an optical grid inserted into the microscope eyepiece.

Whole genome single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping

Genomic DNA from BXH14 Apc Min/+ N2 and N3 mice (along with B6, C3H, and F1 control mice) were genotyped using the Illumina low-density SNP panel (377 SNPs) at the Harvard Partners Center for Genetics and Genomics (Cambridge, MA). Discriminating SNPs and four additional markers (D1Mit206, D2Mit307, D2Mit285, and D18Kcc1) along with coat color (agouti or non-agouti) were analyzed by the Chi-square rxc method with Yates’ correction using GraphPad Software (http://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/contingency1.cfm).

Gene interaction network analysis

Gene interaction networks were identified using Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis (IPA; Ingenuity® Systems, Redwood City, CA). Ensembl gene identifiers for each gene in each region were obtained from the Ensembl database using BioMart. Gene lists were uploaded into IPA and networks of highly interconnected genes were derived from the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledgebase following the provider’s protocol. The statistical significance of interaction networks was determined by the Fisher’s exact test. P-values associated with functional annotations and canonical pathways were corrected for multiple testing using the false discovery rate controlling method of Benjamini and Hochburg (34).

Results

Average polyp numbers in BXH RI Apc Min/+ mice vary from high to low

Although our previous studies had demonstrated that the C3H genome contains modifier loci of the Apc Min mutation (14), we chose to use an existing RI series to aid in the identification of these resistant alleles. The progenitor inbred strains for the BXH RI lines are C57BL/6J (B6) and C3H/HeJ (C3H). Females from the BXH# RI lines were crossed to B6 Apc Min/+ males to produce F1 hybrid progeny (Supplementary Figure S1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Five BXH RI lines (BXH2, BXH4, BXH8, BXH14, and BXH22) and one BXH RC line (B6cC3-1) were tested for their susceptibility or resistance to intestinal tumorigenesis. These lines were chosen because they were homozygous for susceptible Mom1 S alleles, originally derived from the B6 strain, thus eliminating the influence of the Mom1 R locus from this study. The Apc Min/+ offspring from each group, hereafter referred to as BXH# F1, were aged to 110–130 days and scored for adenomas throughout the small intestine and colon.

The small intestinal polyp number for each parental control line showed the expected phenotypic extremes (Table I). The high control B6 Apc Min/+ group had an average of 66±34 polyps, whereas the low control C3H.B6 Mom1 S/S Apc Min/+ group had an average of 10±5 polyps. These data are consistent with results from our previous studies (14).

Table I.

Average polyp number in the intestinal tract of (BXH# x B6 Apc Min/+ )F1 offspring at 110–130 days of agea

| Maternal parent of Apc Min/+ F1 offspringa , b | Average polyp number (±) | Colon polyp incidencec (%) | Number of mice | |

| SI | Colon | |||

| BXH2 | 51±25 | 0.31±0.53 | 29 | 35 |

| BXH4 | 44±18 | 0.60±0.86 | 43 | 30 |

| BXH8 | 28±14 | 0.34±0.67 | 24 | 38 |

| BXH14d | 8±3 | 0.11±0.32 | 11 | 46 |

| BXH22 | 37±21 | 0.40±0.61 | 33 | 48 |

| B6cC3-1 | 57±27 | 0.70±0.88 | 47 | 30 |

| B6 | 66±34 | 1.65±1.81 | 69 | 26 |

| C3H.B6 | 10±05 | 0.31±0.59 | 25 | 32 |

aAll strains shown carry only B6 alleles (susceptible) from at least 136–141Mb at the Mom1 locus on Chromosome 4. Offspring analyzed were derived from four or more mating cages.

bLists the parental control and BXH RI test females crossed to B6 Apc Min/+ males to obtain F1 offspring from each group.

cColon polyp incidence was determined by dividing the number of F1 Apc Min/+ offspring with polyps in the proximal or distal colon by the total number the # mice.

dThe only strain to have one mouse with zero polyps in the intestinal tract was the BXH14 strain.

Based on the average small intestinal polyp numbers (Table I), a gradient in phenotype was observed from high polyp number to low polyp number (B6cC3-1 > BXH2 > BXH4 > BXH22 > BXH8 > BXH14). The average polyp number (60±32) in the B6cC3-1 F1 Apc Min/+ offspring most closely resembled the average polyp number (57±27) in the high control B6 Mom1 S/S Apc Min/+ group, whereas the BXH14 F1 Apc Min/+ group exhibited an average polyp number (8±3) that was less than the average polyp number (10±5) in the low control C3H.B6 Mom1 S/S Apc Min/+ group. Note that the BXH14 F1 Apc Min/+ group was unique in that it exhibited the lowest small intestinal polyp numbers of all lines tested.

Based on the average colon polyp numbers (Table I), a gradient in phenotype was observed from high polyp number to low polyp number (B6cC3-1 > BXH4 > BXH22 > BXH8 > BXH2 > BXH14). The average polyp number (0.70±0.88) in the B6cC3-1 F1 Apc Min/+ offspring was second only to the average polyp number (1.65±1.81) in the high control B6 Mom1 S/S Apc Min/+ group. The BXH14 F1 Apc Min/+ group exhibited the lowest average polyp number (0.11±0.32), which was less than the average polyp number (0.31±0.59) in the low control C3H.B6 Mom1 S/S Apc Min/+ group. For colon polyp incidence (Table I), a gradient in phenotype was observed from high colon polyp incidence to low colon polyp incidence (B6cC3-1 > BXH4 > BXH22 > BXH2 > BXH8 > BXH14). The colon polyp incidence for each parental line exhibits the expected phenotypic extremes of the high control B6 Apc Min/+ group (69%) and the low control C3H.B6 Mom1 S/S Apc Min/+ group (25%). The B6cC3-1 RC line was second only to the phenotype of the B6 Apc Min/+ strain. The BXH14 line was the only Mom1 S/S line that had a lower average colon polyp number and incidence than the C3H.B6 Mom1 S/S Apc Min/+ group (Table I).

Statistical analyses of polyp numbers reveal a unique BXH phenotype

The Student’s t-test was used to evaluate the average number of small intestinal adenomas for each group of Mom1 S/S Apc Min/+ F1 offspring compared with the control groups (and each other) (Supplementary Table SI, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Apc Min/+ F1 offspring of the B6cC3-1 RC line do not significantly differ (P = 0.293) from the high control B6 Apc Min/+ group, but do significantly differ (P < 0.001) from the low control C3H.B6 Apc Min/+ group. Therefore, the B6cC3-1 RC line appears to have inherited susceptible B6 modifier alleles. In contrast, F1 offspring from the BXH14 RI line have an average polyp number that is significantly different (P < 0.001) from the high control B6 Apc Min/+ group and is also significantly different (P = 0.045) from the low control C3H.B6 Apc Min/+ group. In addition, the hybrid BXH14 Apc Min/+ offspring significantly differ (P < 0.001) from all other BXH RI and RC offspring tested (Supplementary Table SI, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Therefore, the BXH14 RI line appears to have inherited the greatest number of C3H modifier alleles that protect against the development of polyposis in the presence of the Apc Min mutation.

The Fisher’s exact probability test was used to evaluate colon polyp incidence for each group of Mom1 S/S Apc Min/+ F1 offspring compared with the control groups (and each other) (Supplementary Table S2, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Apc Min/+ F1 offspring from the B6cC3-1 RC line do not significantly differ (P = 0.110) from the high control B6 Apc Min/+ group. Therefore, this B6cC3-1 RC line appears to have inherited susceptible B6 modifier loci. In contrast, F1 offspring from BXH2, BXH8, BXH14, and BXH22 lines significantly differ (P < 0.005) from the high control B6 Apc Min/+ group, but not the low control C3H.B6 Apc Min/+ group. However, the BXH14 RI line is the only RI line that significantly differs from all but one of the BXH RI lines (P < 0.05), but does not differ from the low control C3H.B6 Apc Min/+ group. With a colon polyp incidence of only 11%, the BXH14 RI line has the lowest colon polyp incidence of any Mom1 S/S Apc Min/+ F1 group. Similar observations were made with respect to colon polyp number (Supplementary Table S3, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

BXH14 Apc Min/+ F1 mice develop fewer polyps in each region of the small intestine and colon compared with susceptible strains

The data demonstrate that the BXH14 RI genome protects against intestinal polyposis in Apc Min/+ F1 hybrids. To determine whether this decrease in polyposis was detectable along the entire small intestine or was limited to a region of the small intestine, we compared average polyp numbers from the resistant BXH14 Apc Min/+ F1 group to the susceptible B6cC3-1 Apc Min/+ F1 group; the B6cC3-1 group was chosen because as an RC line, it has the largest number of B6 alleles of all BXH lines tested. The B6cC3-1 Apc Min/+ F1 group was most like the high control B6 Apc Min/+ group in phenotype (Table I). BXH14 Apc Min/+ F1 mice develop an average of 0.5±1.0, 2.9±3.1, and 5.2±3.6 polyps in the proximal, middle, and distal portions of the small intestine, respectively (Figure 1A). The resistant BXH14 Apc Min/+ F1 mice have significantly fewer (P < 0.0002) polyps in all portions of the small intestine than the susceptible B6cC3-1 Apc Min/+ F1 mice (6.1±3.0, 19.5±11.1, and 32.3±18.4 for proximal, middle, and distal, respectively). Consistent with this finding, the average polyp number for each portion of the small intestine in the BXH14 Apc Min/+ F1 group is significantly different (P < 0.0002) from the average polyp number of the high control B6 Apc Min/+ group (4.7±3.0, 21.5±13.3, and 40.2±20.5 for proximal, middle, and distal, respectively). Therefore, the BXH14 modifier loci affect the entire length of the small intestine. Interestingly, the average polyp number for the proximal (P = 0.0004) and middle (P = 0.0116) small intestine is significantly lower in the BXH14 Apc Min/+ F1 group than the low C3H.B6 Apc Min/+ F1 control group (0.4±0.7, 2.7±1.7, and 4.8±2.5 for proximal, middle, and distal, respectively), suggesting that the overall lower average observed in the BXH14 strain compared with low C3H.B6 Apc Min/+ F1 control group is primarily due to differences in the proximal and middle small intestine.

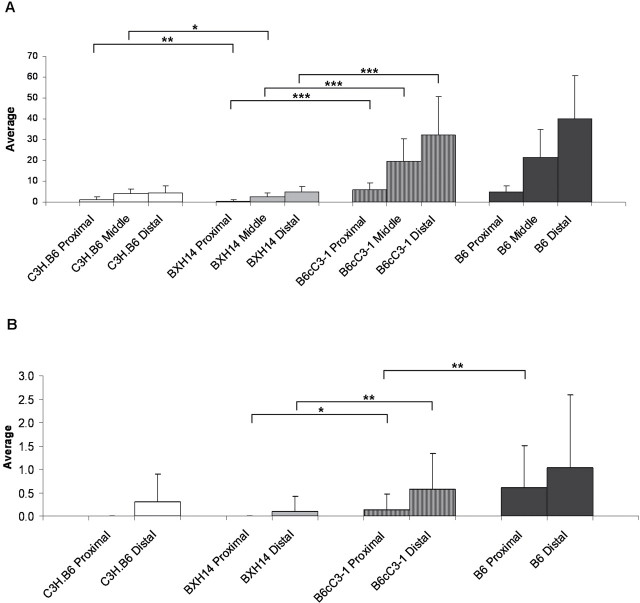

Fig. 1.

Quantitation of intestinal polyposis in control and test mice. Hybrid mice used as controls were (C3H.B6 X B6)F1 Apc Min/+ and (B6 X B6)F1 Apc Min/+. Test mice were (BXH14 X B6)F1 Apc Min/+ and (BcC3-1 X B6)F1 Apc Min/+. All mice were aged to 110–130 days. (A) Average small intestine polyp number (± standard deviation) are shown by region (proximal, middle, and distal). (B) Average colon polyp number (± standard deviation) is shown by region (proximal and distal) (*P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001).

Similar observations were made in the colon (Figure 1B). Significant reductions in average polyp numbers were observed in both the proximal (P = 0.011) and distal (P < 0.002) sections of the colon in the BXH14 Apc Min/+ F1 group (0 and 0.1±0.31 for the proximal and distal colon, respectively) compared with the susceptible B6cC3-1 Apc Min/+ F1 group (0.1±0.4 and 0.6±0.8 for the proximal and distal colon, respectively). Consistent with this finding, the average polyp number for each portion of the colon for the BXH14 Apc Min/+ F1 group is significantly different (P ≤ 0.0002) from the average polyp number of the high control B6 Apc Min/+ group (0.6±0.9 and 1.0±1.6 for the proximal and distal colon). Colon polyp incidence did not vary in the proximal and distal sections between BXH14 Apc Min/+ F1 group and the low control C3H.B6 Apc Min/+ F1 group (0 and 0.3±0.6 for the proximal and distal colon, respectively). Therefore, the BXH14 genome must harbor one or more modifier alleles of the Apc Min mutation that act in a dominant fashion to protect against polyposis along the length of the small intestine and colon.

Whole-genome SNP genotyping of N2 and N3 BXH14 Apc Min/+ mice reveals Mom loci on Chrs 1, 2, 10, and 18

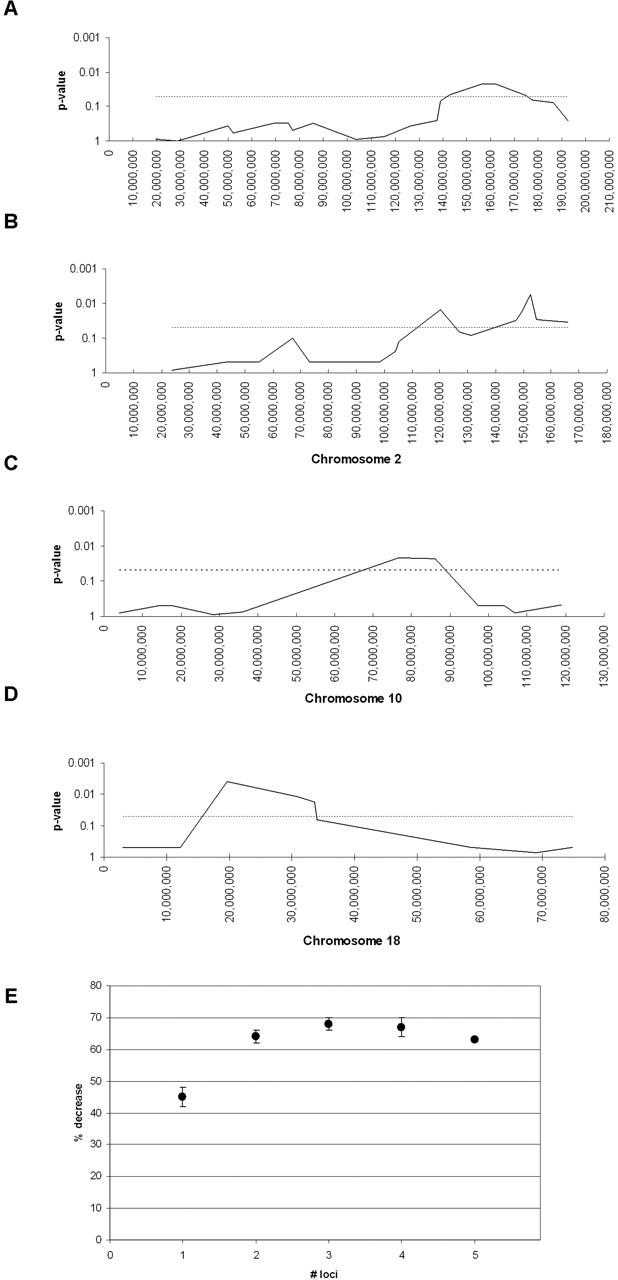

To identify C3H alleles that act to lower polyp number, the Illumina low-density SNP panel was used to genotype 39 BXH14 Apc Min/+ mice from the N2 and N3 backcross generations across the genome (Supplementary Figure S1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Mice were separated into a high group (n = 13) classified as having >35 polyps, and a low group (n = 26) classified as having <35 polyps. A Chi-square rxc test was performed to test each SNP for its prevalence within the high group versus the low group. The results for SNPs that reached statistical significance are shown in Supplementary Table S4, available at Carcinogenesis Online. Five loci were found; in each case, the SNPs that reached the highest statistical significance were C3H alleles. Because these SNPs were flanked by C3H alleles, the low polyp phenotype most likely originated from the C3H genome. These five loci are located on Chrs 1, 2 (two loci), 10, and 18 (Figures 2A–D, respectively); the loci were given Modifier of Min # symbols for Mom14 on Chr 1, Mom15 on Chr 2A (proximal), Mom16 on Chr 2B (distal), Mom17 on Chr 10, and Mom18 on Chr 18.

Fig. 2.

SNP genotyping reveals modifier loci on Chromosomes 1, 2, 10, and 18 in the BXH14 genome. Mom14, Mom15, Mom16, Mom17 and Mom18 are located on (A) Chr 1, (B) Chr 2 (proximal), (B) Chr 2 (distal), (C) Chr 10, and (D) Chr 18. The y-axis shows the P value (P < 0.05 is significant) and the x-axis shows the position of each marker (in Mb). Genomic locations are based on Ensembl Build37 (www.ensembl.org). The Chi-square rxc test was used to determine P values for each marker. Values above the dotted line (P = 0.05) are P < 0.05. Uninformative markers were assigned the value P = 0.5. (E) The quantitative effect of the Mom14-18 loci on polyp number was assessed at the marker with the lowest P value at each locus (Supplementary Table S4 is available at Carcinogenesis Online). The y-axis shows the % decrease at each locus (calculated by taking the average number of polyps for B6/B6 homozygotes versus B6/C3H heterozygotes). Overall % decrease was determined by calculating the average % decrease when Mom14–18 loci are considered individually or in combinations of 2, 3, 4, or 5 loci (Supplementary Table S5 is available at Carcinogenesis Online).

The quantitative effect of the Mom14–18 loci on polyp number was assessed using the marker with the lowest P-value at each Mom locus (Supplementary Table S5, available at Carcinogenesis Online) and calculating the average number of polyps for mice homozygous for the B6 allele versus mice heterozygous for B6 and C3H alleles (Supplementary Table S5, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The data show that when each Mom# locus is considered individually, average polyp number is decreased by 39% for Mom14, 51% for Mom15, 46% for Mom16, 39% for Mom17, and 52% for Mom18 in the heterozygous B6/C3H group compared with the homozygous B6/B6 group. However, when we compared these loci in pairwise combinations, polyp number in the small intestine is decreased by 50–71% (Figure 2E; Supplementary Table SI, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Furthermore, when combinations of three Mom14–18 loci are analyzed together, average polyp number was lowered by 58–75% in the heterozygous B6/C3H group compared with the homozygous B6/B6 group. Regardless of the combination, inheritance of four or more C3H alleles at the Mom14–18 loci resulted in a 61–72% decrease in polyp number.

Based on the increasing level of protection afforded by the combination of all five Mom14–18 loci (Figure 2E), we asked the question of whether topologically defined groups of genes within the Mom14–18 intervals had known interactions. To answer this question, we turned to gene interaction network analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (www.ingenuity.com). Several possible outcomes could result from this type of analysis of gene–gene interactions: (i) no high scoring networks are generated indicating an absence of gene–gene interactions, (ii) high scoring networks are found that primarily contain genes located in a single Mom# region, or (iii) high scoring networks are found that contain genes located in all five Mom# regions. Remarkably, the highest scoring networks were generated when genes located within all five Mom# regions were evaluated together. The top five networks of genes identified by gene interaction network analysis using IPA are shown in Supplementary Table S6 and Figure S2, available at Carcinogenesis Online. These significant P-values are interpreted as known gene–gene interactions that are characteristic of each ensemble of genes. Every network shown contains genes located within all five Mom# loci (Mom14, Mom15, Mom16, Mom17, and Mom18), clearly indicating that there are multiple possibilities by which gene–gene interactions could affect polyposis.

BXH14 contains a unique combination of C3H alleles

The question of whether the C3H haplotype of the BXH14 line was present in other BXH RI lines was answered using The Phenome Database (www.jax.org/phenome). Haplotypes of the Mom14–18 loci were assessed for the BXH2, BXH4, BXH8, BXH14, BXH22, and B6cC3-1 lines (Table II). The BXH14 RI line is the only line tested that contains C3H alleles at all five resistant Mom14, 15, 16, 17, and 18 loci. Consequently, BXH14 exhibited the lowest average small intestine polyp number and the lowest colon polyp incidence of all BXH RI and RC lines tested. The BXH8 RI line contains C3H alleles for Mom15 and Mom16, but has C3H alleles for only a portion of Mom14, Mom17, and Mom18. Based on these findings, we would predict that the BXH8 RI line would have low polyp numbers; Table II shows that this prediction holds true in that the BXH8 F1 offspring had the second lowest average polyp number (28±14) in the small intestine as well as the second lowest colon polyp incidence (24%) (second only to the BXH14 RI line). The remaining BXH2, BXH4, BXH22, and B6cC3-1 lines contain only B6 alleles at two or more Mom14–18 loci, and consequently exhibited higher polyp numbers than BXH14 and BXH8.

Table II.

Effect of haplotype on polyp number in BXH RI and RC strains

| Strain | Average SI polyp number | Colon polyp incidence (%) | Mom14 Chr 1 139-174Mba | Mom15 Chr 2 105-126Mba | Mom16 Chr 2 131-tel Mba | Mom17 Chr 10 36-97Mba | Mom18 Chr 18 12-34Mba |

| BXH2 | 51 | 29 | B | B | B/H/B/He | B/H/Bj | B |

| BXH4 | 44 | 43 | B | B/Hc | H/Bf | B | B/Hl |

| BXH8 | 28 | 24 | B/H/Bb | H | H | H/Bk | B/Hm |

| BXH14 | 8 | 11 | H | H | H/Bg | H | B/Hn |

| BXH22 | 37 | 33 | B | B/Hd | H/B/Hh | B | B |

| B6cC3-1 | 57 | 47 | B | B | B/Hi | B | B |

| B6 | 66 | 69 | B | B | B | B | B |

| C3H.B6 | 10 | 25 | H | H | H | H | H |

aThe Mb positions are based on Ensembl build NCBI m37, April 2007.

bThe haplotype is from H at 152Mb to 157Mb.

cThe haplotype changes from B to H at 125Mb.

dThe haplotype changes from B to H at 119Mb.

eThe haplotype changes from B to H at 161Mb, H to B at 168, and B to H at 178Mb.

fThe haplotype changes from H to B at 138Mb.

gThe haplotype changesf from H to B at 168Mb.

hThe haplotype is B from 145Mb to 148Mb.

iThe haplotype changes from B to H at 170Mb.

jThe haplotype is H from 67Mb to 71Mb.

kThe haplotype changes from H to B at 67Mb.

lThe haplotype changes from B to H at 24Mb.

mThe haplotype changes from B to H at 14Mb.

nThe haplotype changes from B to H at 19Mb.

Criteria to identify Mom14–18 genes

One strategy to find modifier genes is to examine genes implicated in human colon cancers. We compared the Mom14–Mom18 loci to studies identifying genes either (i) mutated in CRC, (ii) found through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), and (iii) identified as common insertions sites through transposon-mediated gene tagging in the mouse (Table III). Each Mom14–18 locus contains genes that (i) have been shown to influence human CRC susceptibility and/or (ii) are mutated in human tumors. The genes that are mutated in CRC were identified by DNA sequencing of human tumors, these genes would presumably act in a cell-autonomous fashion. However, the approach we described is unbiased, and therefore, will detect modifier loci that can act in both non-cell or cell-autonomous fashion with respect to the tumor lineage (Table III).

Table III.

Protein coding genes within Mom14–18 loci implicated in human and mouse tumors

| Mom locus | Mouse chromosome | Human chromosome | Mutated in human CRCa | GWAS geneb | GWAS SNPsb (intergenic) | Common insertion site in GI tract tumorsc | Cn SNPs B6 vs C3Hd |

| Mom14 | 1 | 1q25.1 | TNN | — | |||

| 15q13.3 | FMN1 | rs4779584g | 7 | ||||

| 15q13.3 | GREM1 | rs4779584g | — | ||||

| Mom15 | 2 | 15q13.3 | SCG5 | rs4779584g | — | ||

| 15q21.1 | Eif3j | — | |||||

| 20p13 | TGM3 | — | |||||

| 20p12.3 | FERMT1 f | rs961253 | — | ||||

| Mom16 | 2 | 20p12.3 | BMP2 f | rs961253 | — | ||

| 20p12.1 | Dstn | — | |||||

| 20p11.21 | CD93 | — | |||||

| 20p13 | Csnk2a1 | — | |||||

| 20q13.11 | SRSF6 | — | |||||

| 20q13.2 | AURKA e | — | |||||

| 20q13.32 | GNAS | — | |||||

| 20q13.33 | LAMA5 | rs4925386 | 4 | ||||

| 21q22.3 | MCM3AP | — | |||||

| Mom17 | 10 | 12q22 | METAP2 | — | |||

| 12q22 | Ube2n | — | |||||

| Mom18 | 18 | 18q11.2 | ZNF521 | — | |||

| 18q12.2 | Zfp397 | — |

aGenes listed can be found in the dataset from (46).

bGenes listed can be found in the NHGRI: A Catalog of Published Genome-Wide Association Studies for the disease/trait colorectal cancer (www.genome.gov/26525384).

dGenes listed can be found in The Phenome Database (www.jax.org/phenome).

eThe association of AURKA with human colon cancer as described (47).

fGenes listed directly flank rs961253 (www.ensembl.org).

gGenes listen are all in close proximity to rs4778594 (48).

We identified 20 human genes that are located within the Mom14–18 loci. Of these 20 genes, two of the mouse orthologs of these human genes, Fmn1 and Lama5, contain non-synonymous coding (Cn) SNPs that differ between B6 and C3H. The SNP differences between B6 and C3H may have functional impacts on gene products. However, other types of variants in the Mom14–18 regions may also influence phenotypes in Apc Min/+ mice. Additionally, common insertion sites in 5 of these 20 genes (Eif3j, Dstn, Csnk2a1, Ube2n, and Zfp397) have been observed in gastrointestinal tract tumors (37,38). Although this approach has identified several candidate genes for further characterization, other genes may be responsible for the effect of the Mom14–18 loci.

One expectation to account for the increased protection from polyposis afforded when multiple modifier loci are present in a single mouse (Figure 2E) is that modifier genes encoded by different Mom# loci may interact with each other to alter phenotypes. Gene interaction network analysis using IPA provides one means to elucidate these networks. Supplementary Table S6 and Figure S2, available at Carcinogenesis Online, show a relevant observation from this study, namely that the five highest scoring functional networks contain genes from all five Mom# loci (Mom14–18). Thus, we have clear evidence from this approach that there are gene–gene interactions that encompass all five Mom# loci.

To highlight candidate genes, we conducted a screen to identify genes within the five IPA networks that contained either non-synonymous coding SNPs or structural variants (insertion-deletions) between the B6 and C3H strains (Supplementary Table S7, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Remarkably, 18 of the 70 genes that interact within the top network exhibit non-synonymous coding SNPs (www.jax.org/phenome; Sanger1 and Sanger2 data sets). Networks 2–4 also contain 13–14 genes that have non-synonymous coding changes. Certainly, non-synonymous coding changes are only one type of alteration that could impact gene function. Other genomic, as well as epigenetic, changes could impact the spatial, temporal, and level of gene expression leading to changes in phenotype.

Discussion

This study of the BXH RI lines has revealed five new modifier loci that influence intestinal tumorigenesis in mice carrying the Apc Min mutation. The loci were named Mom14 on Chr 1, Mom15 on Chr 2A (proximal), Mom16 on Chr 2B (distal), Mom17 on Chr 10, and Mom18 on Chr 18. Of the six BXH RI lines tested, the BXH14 RI line had the most protective effect on phenotype, in that both the small intestinal polyp number and the colon polyp incidence were lower than the low control (C3H.B6 Mom1 S/S X B6 Apc Min/+) F1 group. This unique phenotype was recapitulated in subsequent N2 and N3 backcross generations of carrier females mated to B6 Apc Min/+ males.

The BXH14 RI strain contains a rare combination of C3H regions

Overall, BXH14 contains modifier loci with the strongest protective effect against polyposis of all the RI and RC lines tested (Table I). The finding of modifier loci was possible because of the rare combination of C3H alleles that had become fixed in the BXH14 RI line. Because the first step in the generation of an RI line is an intercross between two progenitor strains (B6 and C3H), the F1 progeny inherit half of their alleles from each progenitors’ genome. The second step is an intercross of F1 × F1 to yield the F2 generation. The probability that a single F1 offspring will pass five unlinked loci to their offspring is 1/64 (1/2n, where n = the number of loci). In addition, the probability of selecting two F1 mice that each carry all five loci Mom14–18 from the C3H genome and are mated together is 1/64 × 1/64, or 1/4096. Note that this calculation does not take into account the probability of fixing all five C3H loci in the BXH14 RI line, as the F# intercrosses continue to F20 (a homozygous inbred RI line). However, the probability is slightly higher because two of the modifier loci are linked (Mom15 and Mom16).

The identification of modifier loci was possible because of DNA polymorphisms present in the genomes of the B6 and C3H inbred strains. Because the initial cross was to B6 Apc Min/+ males, it was possible to follow the inheritance of C3H alleles. Each of the Mom14–18 loci has its peak within a region of C3H origin. Thus, it is predicted that the resistant modifier genes should resemble alleles in their C3H progenitor strain. Several possibilities exist for the decreased average polyp numbers detected in the BXH14 strain compared with the progenitor C3H.B6 strain. First, the BXH RI line may have fixed unique mutations/natural variants that arose over time as the line was established. Second, the combinations of chromosomal regions from C3H and B6 present in the BXH14 strain may have affected epistatic relationships between loci, possibly unmasking protective alleles, which now contribute to the resistant phenotype. Third, the BXH14 phenotype could be the result of a combination of C3H alleles and new allelic variants. If such a variant arose within a large contiguous region inherited exclusively from the B6 progenitor, it would not have been detectable in our assay. Thus, genomic sequencing of the BXH14 will help distinguish among these possibilities. Further studies are underway to distinguish among these possibilities and identify the Mom14–18 genes.

Advantages of screens using RI strain sets

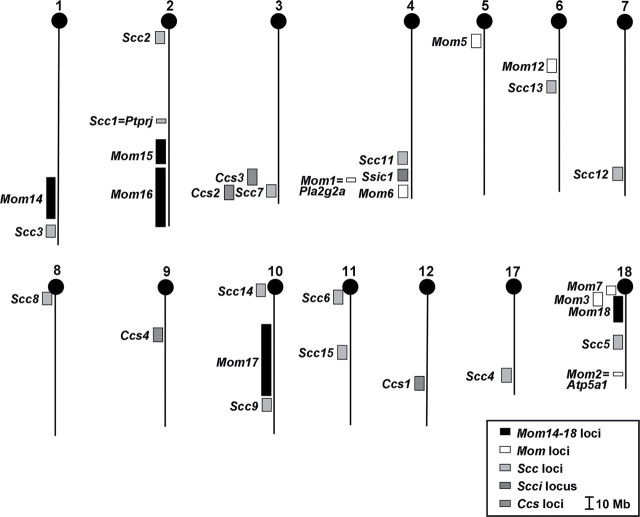

Susceptibility loci for intestinal and CRC have been localized to more than half of all mouse chromosomes (Figure 3). Chr 18 has the highest number of loci (five), while Chrs 2 and 4 have four loci each. Mom14, Mom15, Mom16, and Mom17 map to unique chromosomal locations, whereas Mom18 overlaps with Mom3 (Figure 3). Of the 31 loci shown, the causative genes have been identified for only three loci (Mom1 = Pla2g2a, Mom2 = Atp5a1, and Scc1 = Ptprj) (21,33,35). Although the conceptual strategy for moving from a locus to a gene appears straightforward, several difficulties can be encountered that hinder the identification process. The usual strategy is to establish and evaluate a large quantitative trait loci (QTL) cross (backcross or intercross) between two strains that exhibit the extremes of a phenotype. Once the genotype and phenotype of offspring have been analyzed, congenic lines containing the potential QTL loci are established. However, success is dependent on the quantitative impact of the loci on the phenotype itself (36). If the original phenotype results from the combined action of several unlinked loci, then the probability of recapitulating that phenotype within offspring decreases as the number of loci involved increases.

Fig. 3.

More than 70% of mouse autosomes carry solid tumor susceptibility loci for the small intestine and colon. Mouse chromosomes are shown with centromeres at the top. Positions of susceptibility loci were based on the marker at the peak of the interval. All Mb positions are derived from the Ensembl database (release 61, April 2007) (NCBI m37) (http://www.ensembl.org). With the exception of the Mom14–18 reported here, the remaining loci were previously reported (11,15,16,21,23,33,35,49–62). Mom3, Mom6, Mom12, Scc2-15, and Ssic1 loci are shown ±5Mb from the peak marker. The chromosomal location of Mom13 is unknown.

The use of RI lines may provide an example of how this impediment can be overcome. The strategy would utilize an identity-by-descent approach, where offspring are genotyped and phenotyped at every backcross generation to ensure that the loci responsible for the phenotype are still present in a subset of offspring. In the case of the BXH14 RI line, the initial test of phenotype was performed in a one-step backcross, and the confirmation of phenotype was performed with only two additional backcross generations, thus expediting the process of finding loci compared with large-scale backcrosses and intercrosses. High-throughput sequencing in combination with continued backcrosses to refine the Mom regions can be used to distinguish which genes within each of the Mom14–18 regions are the best candidates for further study.

Network analysis highlights candidate modifier genes

The finding of five non-overlapping networks each composed of different genes from all five Mom# regions opens the door to the possibility that more than one network acts to influence tumor phenotypes. Each IPA network score indicates the likelihood that the assembly of a set of focus genes in a network could be explained by random chance alone. A score of 92, such as that observed for the top scoring Network 1, translates into a 1 × 10−92 probability that the focus genes in Network 1 are together due to random chance (Supplementary Table S7, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Therefore, the combination of genes in Network 1 is highly significant, supporting the utility of our approach. In addition, every gene in Network 1 is located within the Mom14–18 regions.

Interestingly, the top scoring network generated from this unbiased analysis centers on hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 α (Hnf4α), a gene that is essential for normal development of the mouse colon (Supplementary Table S6 and Figure S2A, available at Carcinogenesis Online) (39). Loss of Hnf4α in the gut influences inflammatory homeostasis and affects the balance of differentiation between epithelial and goblet cells (40,41). Tissue-specific knockouts of Hnf4α in Apc Min mice cause suppression of polyposis via a decrease in expression of genes within the oxidoreductase system (42). Furthermore, none of these oxidoreductase target genes were located within the Mom14–18 loci, suggesting that regulation of reactive oxygen species is not the sole mechanism responsible for suppression of polyposis. Further studies are needed to decipher the specific pathways within the networks identified by IPA (Supplementary Table S6 and Figure S2, available at Carcinogenesis Online) that are associated with intestinal and CRC.

The level of protection against polyposis is comparable regardless of the combination of three or more Mom# loci (Figure 2E). Our findings suggest a novel paradigm whereby resistance is determined by varying combinations of a set of protective alleles in different individuals. Reanalyzing GWAS data sets using additive statistical models, in which the aggregate effects of SNPs are taken into account, may have strong implications for the study of human disease risk. However, individual genes, with relatively small effects, such as lowering polyp number by 40%, may not have a strong enough effect to be detected by GWAS (43,44). Therefore, mouse models can inform GWAS, leading to hypothesis-driven screens for loci interacting in an additive fashion (45). Our results highlight the power of using the mouse to inform studies of human cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Tables 1–7 and Figures 1 and 2 can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

National Institutes of Health (CA72027, CA89560, CA120243 to L.D.S. and A.M.B, and F31CA134181-02 to S.C.N]; and The Professor Fredric Rieders Ph.D. Scholarship from the Fredric Rieders Renaissance Foundation to S.C.N.

Acknowledgements

The gene symbols, Mom14–18, were approved for use by Lois Maltais and the International Committee on Standardized Genetic Nomenclature for Mice (www.informatics.jax.org/mgihome/nomen/). We thank Terry Hyslop and Edward Pequignot for aid with statistical analysis, Sankar Addya, Joseph Brunner, Judith Morgan for technical assistance, and Richard Crist, Carlisle Landel, Jacquelyn Roth, Xiang Wang, and Charlene Williams for critical review of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

References

- 1.Half E, et al. Familial adenomatous polyposis. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. (2009);4:22. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Groden J., et al. (1991). Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene Cell 66 589–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Joslyn G., et al. (1991). Identification of deletion mutations and three new genes at the familial polyposis locus Cell 66 601–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goss K.H., et al. (2000). Biology of the adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor J. Clin. Oncol. 18 1967–1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kinzler K. W., et al. (2002). Familial cancer syndromes: colorectal tumors. Vogelstein B., Kinzler K. W. (eds.), In: The Genetic Basis of Human Cancer. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp. 583–612 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lynch H.T. (2008). Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: molecular genetics, genetic counseling, diagnosis and management Fam. Cancer 7 27–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moser A.R., et al. (1990). A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse Science 247 322–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Su L.K., et al. (1992). Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene Science 256 668–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moser A.R., et al. (1995). ApcMin: a mouse model for intestinal and mammary tumorigenesis Eur. J. Cancer 31A 1061–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moser A.R., et al. (1992). The Min (multiple intestinal neoplasia) mutation: its effect on gut epithelial cell differentiation and interaction with a modifier system J. Cell Biol. 116 1517–1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dietrich W.F., et al. (1993). Genetic identification of Mom-1, a major modifier locus affecting Min-induced intestinal neoplasia in the mouse Cell 75, 631–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gould K.A., et al. (1996). Mom1 is a semi-dominant modifier of intestinal adenoma size and multiplicity in Min/+ mice Genetics 144 1769–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koratkar R., et al. (2002). The CAST/Ei strain confers significant protection against Apc(Min) intestinal polyps, independent of the resistant modifier of Min 1 (Mom1) locus Cancer Res. 62 5413–5417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koratkar R., et al. (2004). Analysis of reciprocal congenic lines reveals the C3H/HeJ genome to be highly resistant to ApcMin intestinal tumorigenesis Genomics 84, 844–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oikarinen S.I., et al. (2009). Genetic mapping of Mom5, a novel modifier of Apc(Min)-induced intestinal tumorigenesis Carcinogenesis 30, 1591–1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kwong L.N., et al. (2007). Identification of Mom7, a novel modifier of Apc(Min/+) on mouse chromosome 18 Genetics 176 1237–1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Siracusa L.D., et al. (2004). Genome-wide modifier screens: how the genetics of cancer penetrance may shape the future of prevention and treatment. In Brenner C, Duggan D. (eds) Oncogenomics: Molecular Approaches to Cancer John Wiley & Sons; Inc, New York, NY,pp. 255–290 [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCart A.E., et al. (2008). Apc mice: models, modifiers and mutants Pathol. Res. Pract. 204 479–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kwong L.N., et al. (2009). APC and its modifiers in colon cancer Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 656 85–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gould K.A., et al. (1996). Genetic evaluation of candidate genes for the Mom1 modifier of intestinal neoplasia in mice Genetics 144 1777–1785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. MacPhee M., et al. (1995). The secretory phospholipase A2 gene is a candidate for the Mom1 locus, a major modifier of ApcMin-induced intestinal neoplasia Cell 81 957–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cormier R.T., et al. (1997). Secretory phospholipase Pla2g2a confers resistance to intestinal tumorigenesis Nat. Genet. 17 88–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cormier R.T., et al. (2000). The Mom1AKR intestinal tumor resistance region consists of Pla2g2a and a locus distal to D4Mit64 Oncogene 19, 3182–3192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bailey D.W. (1981). Recombinant inbred strains and bilineal congenic strains. In: The Mouse in Biomedical Research Foster H.J., Small J.D., Fox J.G. (eds). Vol. 1 Academic Press; New York, NY: pp. 223–239 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Churchill G.A. (2007). Recombinant inbred strain panels: a tool for systems genetics Physiol. Genomics 31 174–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams R.W., et al. The genetic structure of recombinant inbred mice: high-resolution consensus maps for complex trait analysis. Genome Biol. (2001);2:RESEARCH0046. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-11-research0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Flint J., et al. (2005). Strategies for mapping and cloning quantitative trait genes in rodents Nat. Rev. Genet. 6 271–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Frankel W.N. (1995). Taking stock of complex trait genetics in mice Trends Genet. 11 471–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Belknap J.K., et al. (2001). The replicability of QTLs for murine alcohol preference drinking behavior across eight independent studies Mamm. Genome 12 893–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fortin A., et al. (2007). The AcB/BcA recombinant congenic strains of mice: strategies for phenotype dissection, mapping and cloning of quantitative trait genes Novartis Found. Symp ., 281 141–153; discussion 153–155, 208–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Demant P., et al. (1986). Recombinant congenic strains--a new tool for analyzing genetic traits determined by more than one gene Immunogenetics 24 416–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Luongo C., et al. (1994). Loss of Apc+ in intestinal adenomas from Min mice Cancer Res. 54 5947–5952 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Silverman K.A., et al. (2002). Identification of the modifier of Min 2 (Mom2) locus, a new mutation that influences Apc-induced intestinal neoplasia Genome Res. 12 88–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Benjamini Y., et al. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Statist. Soc. B. 57 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ruivenkamp C.A., et al. (2002). Ptprj is a candidate for the mouse colon-cancer susceptibility locus Scc1 and is frequently deleted in human cancers Nat. Genet., 31 295–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Demant P. (2003). Cancer susceptibility in the mouse: genetics, biology and implications for human cancer Nat. Rev. Genet. 4 721–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Starr T.K., et al. (2009). A transposon-based genetic screen in mice identifies genes altered in colorectal cancer Science 323, 1747–1750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Starr T.K., et al. (2011). A sleeping Beauty transposon-mediated screen identifies murine susceptibility genes for adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc)-dependent intestinal tumorigenesis Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108 5765–5770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Garrison W.D., et al. (2006). Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha is essential for embryonic development of the mouse colon Gastroenterology 130 1207–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cattin A.L., et al. (2009). Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha, a key factor for homeostasis, cell architecture, and barrier function of the adult intestinal epithelium Mol. Cell Biol. 29 6294–6308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darsigny M., et al. Loss of hepatocyte-nuclear-factor-4alpha affects colonic ion transport and causes chronic inflammation resembling inflammatory bowel disease in mice. PLoS One. (2009);4:e7609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Darsigny M., et al. (2010). Hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha promotes gut neoplasia in mice and protects against the production of reactive oxygen species Cancer Res. 70 9423–9433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jakobsdottir J., et al. Interpretation of genetic association studies: markers with replicated highly significant odds ratios may be poor classifiers. PLoS Genet. (2009);5:e1000337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. He J., et al. (2011). Generalizability and epidemiologic characterization of eleven colorectal cancer GWAS hits in multiple populations Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 20 70–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hunter K.W., et al. (2008). The future of mouse QTL mapping to diagnose disease in mice in the age of whole-genome association studies Annu. Rev. Genet. 42 131–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wood L.D., et al. (2007). The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers Science 318, 1108–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ewart-Toland A., et al. (2003). Identification of Stk6/STK15 as a candidate low-penetrance tumor-susceptibility gene in mouse and human Nat. Genet. 34 403–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jaeger E., et al. (2008). Common genetic variants at the CRAC1 (HMPS) locus on chromosome 15q13.3 influence colorectal cancer risk Nat. Genet. 40 26–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Moen C.J., et al. (1992). Scc-1, a novel colon cancer susceptibility gene in the mouse: linkage to CD44 (Ly-24, Pgp-1) on chromosome 2. Oncogene 7 563–566 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jacoby R.F., et al. (1994). Genetic analysis of colon cancer susceptibility in mice Genomics 22 381–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fijneman R.J., et al. (1995). A gene for susceptibility to small intestinal cancer, ssic1, maps to the distal part of mouse chromosome 4 Cancer Res. 55 3179–3182 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. van Wezel T., et al. (1996). Gene interaction and single gene effects in colon tumour susceptibility in mice Nat. Genet. 14, 468–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. van Wezel T., et al. (1999). Four new colon cancer susceptibility loci, Scc6 to Scc9 in the mouse Cancer Res. 59 4216–4218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Angel J.M., et al. (2000). A locus that influences susceptibility to 1, 2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon tumors maps to the distal end of mouse chromosome 3 Mol. Carcinog. 27, 47–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ruivenkamp C.A., et al. (2003). Five new mouse susceptibility to colon cancer loci, Scc11-Scc15 Oncogene 22 7258–7260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Haines J., et al. (2005). Genetic basis of variation in adenoma multiplicity in ApcMin/+ Mom1S mice Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102 2868–2873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Suraweera N., et al. (2006). Genetic determinants modulate susceptibility to pregnancy-associated tumourigenesis in a recombinant line of Min mice Hum. Mol. Genet ., 15, 3429–3435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Baran A.A., et al. (2007). The modifier of Min 2 (Mom2) locus: embryonic lethality of a mutation in the Atp5a1 gene suggests a novel mechanism of polyp suppression Genome Res. 17, 566–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Meunier C., et al. (2010). Characterization of a major colon cancer susceptibility locus (Ccs3) on mouse chromosome 3 Oncogene 29 647–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Crist R.C., et al. (2011). Identification of Mom12 and Mom13, two novel modifier loci of Apc (Min)-mediated intestinal tumorigenesis Cell Cycle 10 1092–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Moen C.J., et al. (1996). Fine mapping of colon tumor susceptibility (Scc) genes in the mouse, different from the genes known to be somatically mutated in colon cancer Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 1082–1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Van Der Kraak L., et al. (2010). A two-locus system controls susceptibility to colitis-associated colon cancer in mice. Oncotarget 1 436–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.