Abstract

The pH of xylem sap from tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) plants increased from pH 5.0 to 8.0 as the soil dried. Detached wild-type but not flacca leaves exhibited reduced transpiration rates when the artificial xylem sap (AS) pH was increased. When a well-watered concentration of abscisic acid (0.03 μm) was provided in the AS, the wild-type transpirational response to pH was restored to flacca leaves. Transpiration from flacca but not from wild-type leaves actually increased in some cases when the pH of the AS was increased from 6.75 to 7.75, demonstrating an absolute requirement for abscisic acid in preventing stomatal opening and excessive water loss from plants growing in many different environments.

Jones (1980) and Cowan (1982) were the first to suggest that plants can “measure” soil water status independently of shoot water status via the transfer of chemical information from roots to shoots. Dehydrating roots in drying soil synthesize ABA more rapidly than fully turgid tissue, and resultant increases in the ABA concentration of xylem sap flowing toward the still-turgid shoot constitutes a chemical signal to the leaves (for review, see Davies and Zhang, 1991): the xylem vessels give up their contents to the leaf apoplast, thereby increasing the ABA concentration in this compartment. ABA receptors on the external surface of stomatal guard cells respond to the apoplastic ABA concentration (Hartung, 1983; Anderson et al., 1994; but see Schwartz et al., 1994). When bound, the receptors transduce a reduction in guard cell turgor, which leads to stomatal closure (Assmann, 1993). This maintains shoot water potential despite the reduction in soil water availability.

Another chemical change related to soil drying in the absence of a reduction in shoot water status is an increase in the pH of the xylem sap flowing from the roots (Schurr et al., 1992). The pH of the xylem and/or apoplastic sap of plants can also change dramatically in response to soil flooding, diurnal or annual rhythms, and mineral nutrient supply (Table I) in the absence of concomitant changes in either root or shoot water status. We already know that, like the increase in xylem ABA concentration described above, an increase in xylem pH can also act as a signal to leaves to close their stomata (Wilkinson and Davies, 1997). Since the conditions that affect xylem/apoplastic pH can also affect transpiration (light intensity [Cowan et al., 1982]; soil drying [Davies and Zhang, 1991]; nitrate supply [Clarkson and Touraine, 1994]; soil flooding [Else, 1996]), the possibility exists that the pH change that they induce could be the means by which they alter stomatal aperture.

Table I.

pH changes that occur in plant xylem or apoplastic sap under various conditions

| Species | Source of Sap | pH Change | Conditions of Change | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phaseolus coccineus | Root xylem | 6.5–7.0 | Wet soil–2-d drought | Hartung and Radin (1989) |

| Anastatica hierochuntica | Root xylem Shoot xylem | 6.5–7.1 6.5–7.6 | Wet soil–dry soil | Hartung and Radin (1989) |

| Helianthus annuus | Shoot xylem | 5.8/6.6–7.1 | High soil water–below 0.13 g/g | Gollan et al. (1992) |

| C. communis | Shoot xylem | 6.0–6.5/6.7 | Wet soil–4- to 5-day drought | Wilkinson and Davies (1997) |

| L. esculentum | Root xylem at 0.1 MPa | 6.13–6.74 | Drained soil–flooded soil | Else (1996) |

| Ricinus communis | Shoot xylem | 6.0–6.6 | End of night–end of day | Schurr and Schulze (1995) |

| Helianthus annuus | Leaf apoplast | 5.7–6.4 | Light–dark (+2.5 mm nitrate) | Hoffmann and Kosegarten (1995) |

| Samanea pulvinus | Extensor apoplast | 6.2–6.7 | White light–dark | Lee and Satter (1989) |

| Robinia wood | Shoot xylem | 6.0–5.0–5.5 | Jan–April/May–Nov/Dec | Fromard et al. (1995) |

| Actinidea chinensis | Shoot xylem | 5.3–6.2 | Spring–rest of year | Ferguson et al. (1983) |

| Betula pendula | Shoot xylem | 7.5/8.0–5.7 | Rest of year–catkin bud break | Sauter and Ambrosius (1986) |

| Hordeum vulgare | Leaf apoplast | 6.6–7.3 | Control–brown rust infected | Tetlow and Farrar (1993) |

| H. annuus | Leaf apoplast | 6.8–7.4 | Low nitrate–high nitrate | Dannel et al. (1995) |

| H. annuus | Leaf apoplast | 6.0–6.5 6.2–7.0 | NH4NO3−–NO3− NH4NO3−–HCO3− | Mengel et al. (1994) |

It was originally suggested that an increase in xylem sap pH could putatively enhance stomatal closure by changing the distribution of the ABA that is present in all nonstressed plants at a low “background” concentration, without requiring de novo ABA synthesis (Schurr et al., 1992; Slovik and Hartung, 1992a, 1992b). This hypotheses is built on the well-known fact that weak acids such as ABA accumulate in more alkaline compartments (Kaiser and Hartung, 1981). More recently, Wilkinson and Davies (1997) and Thompson et al. (1997) directly demonstrated that increases in xylem sap pH reduced rates of water loss from Commelina communis and tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) leaves detached from well-watered plants. This was found to be mediated by the relatively low endogenous concentration of ABA (about 0.01 mmol m−3) contained in the xylem vessels and apoplast of these leaves, a concentration of ABA that did not itself affect transpiration at a well-watered sap pH of 6.0. The mechanism by which the combination of high sap pH and such a low concentration of ABA was able to increase the apoplastic ABA concentration sufficiently to close stomata was also elucidated: the mesophyll and epidermis cells of these leaves had a greatly reduced ability to sequester ABA away from the apoplast when the pH of the latter was increased by the incoming xylem sap (Wilkinson and Davies, 1997).

In contrast to the indirect ABA-mediated effect of pH on stomata, it was also demonstrated that increasing the pH of the external solution (from 5.0 to 7.0) bathing isolated abaxial epidermis tissue peeled from well-watered C. communis leaves actually increased stomatal aperture (Wilkinson and Davies, 1997). Mechanisms for this direct effect of pH on guard cells have been speculated on by Thompson et al. (1997). If this process were to occur in vivo, environments that increase xylem sap pH could potentially induce excessive water loss from the plants experiencing them, over and above rates of transpiration occurring in unstressed plants. The latter may contain stomata with apertures smaller than the maximum that is possible, even under favorable local conditions. It was assumed that high-pH-induced apoplastic ABA accumulation in C. communis in vivo was sufficient to override the direct stomatal opening effect seen in the isolated tissue (Wilkinson and Davies, 1997). To test these possibilities, effects of pH on transpiration rates from leaves of the flacca mutant of tomato were investigated. flacca does not synthesize ABA as efficiently as wild-type tomato (Parry et al., 1988; Taylor et al., 1988). It contains a very low endogenous ABA concentration (Tal and Nevo, 1973), although it retains the ability to respond to an application of this hormone (Imber and Tal, 1970). The results demonstrate not only that ABA mediates high xylem sap pH-induced stomatal closure but also that it is necessary to prevent high xylem sap pH-induced stomatal opening and dangerously excessive water loss.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Seeds of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L. cv Ailsa Craig) (wild-type) or flacca were sown in Levington F2 compost (Fisons, Ipswich, UK). Seedlings were transplanted to 0.125- × 0.125-m pots in a greenhouse with a day/night temperature of 22/15°C. They were watered daily with tap water and weekly with full-strength Hoagland nutrient solution (Epstein, 1972). flacca plants were sprayed twice weekly with 0.2 mmol m−3 (+)-ABA to keep growth conditions between the two cultivars as similar as possible. Plants 4 to 5 weeks of age were watered twice daily. At this stage flacca plants were no longer sprayed with ABA to prevent contamination of subsequent experiments. Although humidity was not controlled, the increased water supply prevented leaf wilt, but leaf surface area eventually became smaller than that of wild-type leaves. When plants were 6 to 9 weeks old, single leaflets from the two or three youngest fully expanded wild-type leaves were used as a source of experimental material. In the case of flacca, the three most apical leaflets from appropriate leaves were detached together and used as a single experimental unit to standardize leaf surface area between the two cultivars.

Chemicals

Synthetic racemic (±)-ABA was obtained from Lancaster Synthesis Ltd. (Morecambe, Lancashire, UK). General reagents used in experiments were all BDH Analar grade from Sigma.

Measurement of Xylem Sap pH, Shoot Water Potential, and Soil Water Content

Fifty-two wild-type plants were watered as described above, whereas another group of 52 plants was left unwatered for 1 to 2 d. Several measurements were taken from these plants during daylight during the 48-h period, and correlations between them were investigated. We found no evidence for a diurnal effect on xylem sap pH when soil moisture content was kept high (results not shown).

The stem was cut 30 mm above the soil surface, and the remaining stump was blotted to remove any contaminants from cut cells. The pH of xylem sap exuded from the stump was measured within 2 min by immersing an Orion combination needle pH electrode (Orme Scientific Ltd., Manchester, UK) into the droplet. Exudation rates from de-topped roots are slow and the sap may become more acidic than that in an intact transpiring plant (by up to 0.5 pH unit after 9 h [Schurr and Schulze, 1995]); however, the reduction in flow rate is proportional between stressed and unstressed plants (Else, 1996). To artificially increase sap flow rates by pressurizing the root system can dehydrate the tissue (Hartung and Radin, 1989), and this may be disproportionate between stressed and unstressed plants.

To measure water potential, the shoot from the same plant was quickly sealed into a pressure bomb (Soil Moisture Equipment, Santa Barbara, CA). The chamber was gradually pressurized until the meniscus of the xylem sap became visible at the cut tissue surface, and the pressure was noted.

The soil in which the plant had been growing was separated from the roots and weighed, dried in an oven for 2 d, and reweighed to calculate gravimetric soil water content.

Transpiration Bioassay

Each experiment described below was carried out on a separate batch of plants of an equivalent age. Leaflets were removed from plants that had been kept in the dark for 1 h, and the petiole was recut under degassed distilled water to avoid embolism. They were immediately transferred to plastic vials of 7.0 × 10−6 m−3 volume that were covered with aluminum foil secured with Parafilm (American National Can, Greenwich, CT) to reduce evaporation. A “V”-shaped slit was cut into the foil so that the leaf could have access to the contents of the vial. Each of these contained 5.0 × 10−6 m−3 of AS (unless otherwise stated): 1.0 mol m−3 KH2PO4, 1.0 mol m−3 K2HPO4, 1.0 mol m−3 CaCl2, 0.1 mol m−3 MgSO4, 3.0 mol m−3 KNO3, and 0.1 mol m−3 MnSO4 buffered to specified pHs with 1.0 mol L−1 HCl or KOH, with or without 0.03 mmol m−3 (+)-ABA (the approximate concentration present in the xylem sap of well-watered, well-drained tomato plants [Else, 1996]). The vials were randomized in a growth cabinet (PPFD 500 μmol m−2 s−1) and weighed every 30 min for 3 to 4 h, after which time the leaf area above the foil was measured in a planimeter (Paton Industries, Pty. Ltd., South Australia). The transpirational rate of water loss was calculated per unit leaf area (single surface) every 30 min.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Correlations between Xylem Sap pH, Soil Water Content, and Shoot Water Potential

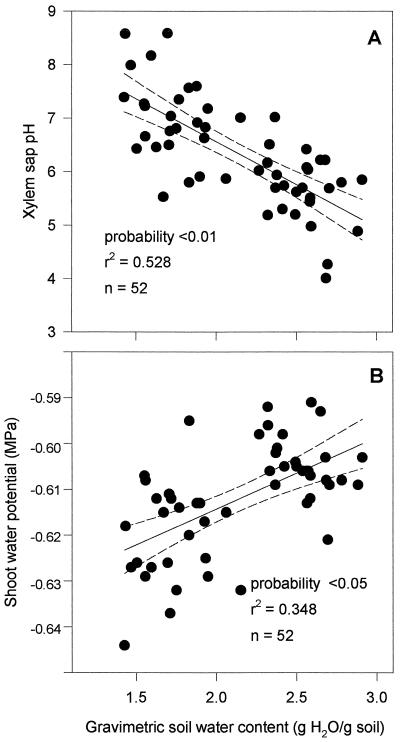

The pH of xylem sap from wild-type tomato plants grown as described above was negatively correlated with gravimetric soil water content (Fig. 1A), which only affected shoot water potential within a range of 0.05 MPa (Fig. 1B). Sap pH increased over a range of 3 units as soil water content decreased, although most readings were between pH 5.5 and 7.5. These results are comparable to those in which xylem sap pH was measured over a drying period in other species (Table I) except in castor bean, in which sap became more acidic with drought (Schurr and Schulze, 1996), and the range of pH covered here is similar to that detected in B. pendula shoot xylem sap by Sauter and Ambrosius (1986). As expected (Davies and Zhang, 1991), these changes were detected in plants that exhibited only very small variations in shoot water potential, indicating that they must be signals arising from an effect of decreased soil water on the root.

Figure 1.

Effect of gravimetric soil water content on the pH (A) of xylem sap expressed within 2 min from 30-mm shoot stumps and on the water potential (B) of shoots cut from 6- to 9-week-old wild-type tomato plants. Linear regressions with 95% confidence limits are shown.

Several theories exist to explain how the environment might control xylem sap pH. It has long been known that xylem parenchyma cells surrounding the vessels can control the composition of the transpiration stream (Pitman et al., 1977). More recently, Fromard et al. (1995) found that xylem vessel-associated cells from Robinia pseudoacacia wood, which contain high concentrations of plasma membrane proton-pumping ATPases, were able to influence xylem sap pH. Presumably this also occurs in roots. There is some evidence that drought-related and PAR-related pH changes in xylem/apoplastic sap might result from differential proton-pumping activity in the cells of these plants (Hartung and Radin, 1989; Marré et al., 1989; Hoffmann and Kosegarten, 1995). It is not known, however, whether proton-pumping rates are directly affected by tissue dehydration, i.e. whether the pH changes are confined to the root or whether they are indirectly influenced by alterations in ion concentrations in the sap flowing from roots adjacent to drying soil. If the effect of drought on ATPase activity is indirect, reduced proton pumping from shoot xylem parenchyma cells could enhance increases in the pH of the sap flowing upward from the root. Some evidence exists for the latter, since increases in stress-induced sap pH tend to become more marked when measured farther up the plant stem (Hartung and Radin, 1989; Hoffmann and Kosegarten, 1995). These findings could also be explained by the possibility that xylem/apoplastic pH might be controlled by ionic exchange between sap constituents and the walls of adjacent cells (Ryan et al., 1992). Since the ionic composition of sap flowing from the roots is changed by the proximity of drying soil (Gollan et al., 1992), the pattern of exchange with wall-bound ions along the length of the transpiration stream could be altered, thereby changing its pH.

Some authors have detected a correlation between the pH and the sugar composition of the leaf apoplast (Sauter and Ambrosius, 1986; Tetlow and Farrar, 1993). Since sugar uptake by the phloem involves ATPase activity (Delrot and Bonnemain, 1981), apoplastic sugar content may also influence apoplastic pH and could explain some of the changes in sap pH with time of day or year.

An alternative proposal is that nitrate levels in xylem sap may somehow control its pH (Raven and Smith, 1976; Allen et al., 1988). Increasing the nitrate concentration supplied to roots of sunflower plants has recently been demonstrated to increase the apoplastic pH of leaves when sap was extracted by centrifugation (Dannel et al., 1995) or investigated with fluorescent dyes (Mengel et al., 1994; Hoffmann and Kosegarten, 1995). It is thought that proton-nitrate cotransport over the plasma membrane of leaf cells and localized production of OH− after nitrate reduction in the cytoplasm are responsible for increased apoplastic pH (Ullrich, 1992). However, increased nitrate levels in xylem sap are not always associated with increases in pH, and in fact, the reverse can be true (Gollan et al., 1992; Jackson et al., 1996). The fact that some plant species reduce nitrate in the roots and others perform this vital function in shoots (Andrews, 1986) could explain some of the variability in xylem/apoplastic pH between species and in the effects of environmental conditions on their physiology.

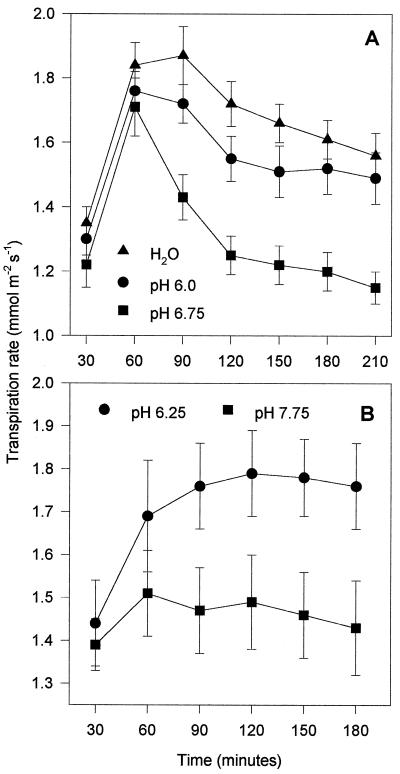

Effects of pH on Transpiration from Wild-Type Leaves

The transpiration rates of freshly detached wild-type tomato leaflets taking up AS buffered to a well-watered pH of 6.0 were comparable to those of leaves taking up distilled water only, indicating that AS itself had no effect on stomatal aperture (Fig. 2A). Transpiration was reduced from control (well-watered) levels within 90 min when the pH of the AS supplied to the leaves was adjusted to the pH of xylem sap extracted from plants growing in drying soils (Fig. 2A, pH 6.75; Fig. 2B, pH 7.75). These findings support the hypothesis that increased sap pH closes stomata, but they do not provide evidence for the involvement of ABA in this process. For C. communis such evidence was provided (Wilkinson and Davies, 1997) by preincubating leaves overnight in distilled water with or without a low concentration of ABA, equivalent to that found in xylem sap from well-watered plants (0.01 mmol m−3). Only when ABA had been present were the leaves able to respond to subsequent treatments with high- pH buffers. It was assumed that the solution in which the leaves were preincubated replaced the contents of the xylem vessels and the apoplast of the fresh leaf. High-pH-induced ABA accumulation in the apoplast adjacent to the guard cells was no longer possible in leaves treated in water alone and, consequently, stomata remained open.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the effect of water (A) and AS pH (A and B) on the transpiration rate of detached wild-type tomato leaflets in the light. The transpiration rate was calculated for each leaf every 30 min and expressed as a mean (n = 8) ± se.

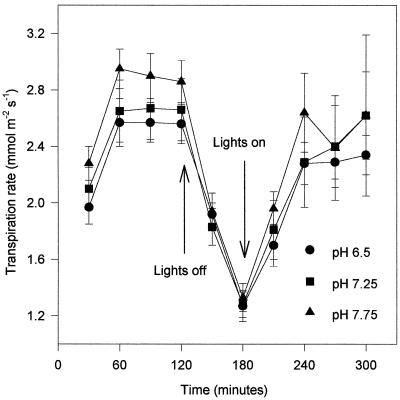

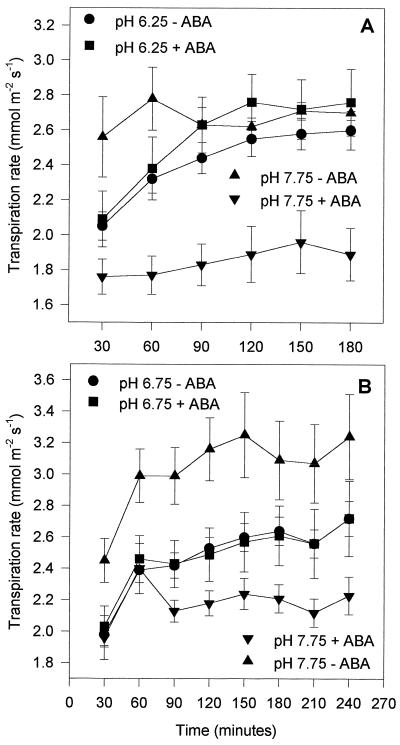

High pH Only Reduces Transpiration from flacca Leaves in Combination with a Low Concentration of ABA

Figure 3 illustrates an example of several experiments that showed that flacca leaf transpiration rates were not reduced by pH of up to 7.75 (within the range detected in droughted tomato plants), although the stomata were able to close in response to decreased PAR. This is in direct contrast to the situation in wild-type leaves (Fig. 2). However, when a low, well-watered concentration of (+)-ABA (0.03 mmol m−3) was supplied in the AS, which did not reduce transpiration at pH 6.25, the high pH mimicked its normal effect in wild-type leaves, i.e. it reduced the rate of transpirational water loss (Fig. 4). This is direct evidence that ABA is an absolute requirement for the reduction of transpirational water loss from detached tomato leaves by increased xylem sap pH.

Figure 3.

Effect of AS pH and PAR (PPFD 500 μmol m−2 s−1 and darkness) on the transpiration rate of detached flacca leaves. Leaves were preincubated in AS for 1 h in the dark. The transpiration rate was calculated for each leaf every 30 min and expressed as a mean (n = 4–8) ± se.

Figure 4.

Effect of AS pH on the transpiration rate of detached flacca leaves in the light in the presence and absence of 0.03 μm (+)-ABA. Leaves were preincubated in AS for 1 h in the dark. It is assumed that the endogenous ABA content of the leaves used in A was higher than that in the leaves used in experiment B. Transpiration rates were calculated and expressed as in Figure 3 (n = 4–6).

High pH Can Directly Increase Transpiration from flacca Leaves

Figure 4A also shows that in the absence of ABA the transpiration rate of flacca leaves at pH 7.75 was initially higher than at pH 6.25. This effect was present to different degrees in different experiments and was sometimes completely absent (Fig. 3). Figure 4B illustrates an example of a group of experiments in which, in the absence of exogenous ABA, the transpiration rate at pH 7.75 was steadily much higher than at pH 6.75. This is a novel finding in whole leaves, although as described above there is evidence that increasing the external pH opens stomata in isolated abaxial epidermal peels of C. communis (Wilkinson and Davies, 1997; see also Schwartz et al., 1994).

That increased transpirational water loss from flacca leaves was induced by high xylem sap pH to different degrees in different experiments could have been accounted for by a variability in the endogenous, although very low, ABA concentration between individual flacca plants or between the batches of plants used for each experiment due, for example, to day-to-day fluctuations in greenhouse temperature, light intensity, and/or humidity. Preliminary measurements of bulk leaf ABA by radioimmunoassay (for protocol, see Wilkinson and Davies, 1997) revealed that flacca leaves picked on different days contained between 0.1 and 1.5 nmol g−1 dry weight ABA, whereas wild-type tomato leaves contained between 2.0 and 6.0 nmol g−1 dry weight ABA. Bulk leaf ABA is not always a good measure of xylem ABA, and cross-reactive substances in tomato that interfere with the radioimmunoassay can result in considerable overestimations of the ABA concentration actually present (Else et al., 1996). However, these results demonstrate the potential for the endogenous ABA concentration of an individual flacca plant to vary on a daily basis. The plants used in the experiment illustrated in Figure 3 may have contained closer to 1.5 nmol g−1 dry weight bulk leaf ABA, whereas those used in Figure 4B may have had a 15-fold lower concentration, with those in Figure 4A containing an intermediate amount.

That such small concentrations of ABA in the AS (up to 0.03 mmol m−3) were all that was required to inhibit the pH-induced stomatal opening effect seen in some experiments (Fig. 4B) demonstrates the potency of this hormone and its great capacity for plant protection, at least in tomato.

CONCLUSIONS

These findings show that the increases in xylem sap pH described in Table I have the potential to widen the stomata in the leaves of these plants, were it not for the ubiquitous presence of a low background (“well-watered”) concentration of ABA. The pH signal is potentially harmful, and since it seems to be such a common response to changes in the external environment that are not necessarily otherwise stressful, plants require ABA to function normally, even when they are not experiencing a water deficit in any of their tissues. The plant has used a potentially harmful chemical change induced by a plethora of different factors to actually improve its water use efficiency and therefore its chances of survival.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to thank Mark Bacon (Lancaster University) for help with data presentation.

Abbreviation:

- AS

artificial sap

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council, UK.

LITERATURE CITED

- Allen S, Raven JA, Sprent JI. The role of long-distance transport in intracellular pH regulation in Phaseolus vulgaris grown with ammonium or nitrate as nitrogen source, or nodulated. J Exp Bot. 1988;202:513–528. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BE, Ward JM, Schroeder JI. Evidence for an extracellular reception site for abscisic acid in Commelina guard cells. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:1177–1183. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.4.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews M. The partitioning of nitrate assimilation between root and shoot of higher plants. Plant Cell Environ. 1986;9:511–519. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann SM. Signal transduction in guard cells. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:345–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson DT, Touraine B. Morphological responses of plants to nitrate-deprivation: a role for abscisic acid? In: Roy J, Garnier E, editors. A Whole Plant Perspective on Carbon-Nitrogen Interactions. The Hague: SPB Academic Publishing; 1994. pp. 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan IR. Regulation of water use in relation to carbon gain in higher plants. In: Lange OL, Novel PS, Osmond CB, Zeigler H, editors. Physiological Plant Ecology II. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1982. pp. 589–614. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan IR, Raven JA, Hartung W, Farquhar GD. A possible role for abscisic acid in coupling stomatal conductance and photosynthetic carbon metabolism in leaves. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1982;9:489–498. [Google Scholar]

- Dannel F, Pfeffer H, Marschner H. Isolation of apoplasmic fluid from sunflower leaves and its use for studies on influence of nitrogen supply on apoplasmic pH. J Plant Physiol. 1995;146:273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Davies WJ, Zhang J. Root signals and the regulation of growth and development of plants in drying soil. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42:55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Delrot S, Bonnemain JL. Involvement of protons as a substrate for the sucrose carrier during phloem loading in Vicia faba leaves. Plant Physiol. 1981;67:560–564. doi: 10.1104/pp.67.3.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else MA (1996) Xylem-borne messages in the regulation of shoot responses to soil flooding. PhD thesis. Lancaster University, UK

- Else MA, Tiekstra AE, Croker SJ, Davies WJ, Jackson MB. Stomatal closure in flooded tomato plants involves abscisic acid and a chemically unidentified anti-transpirant in xylem sap. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:239–247. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.1.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein E (1972) The media of plant nutrition. In Mineral Nutrition of Plants: Principles and Perspectives. John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp 29–49

- Ferguson AR, Eiseman JA, Leonard JA. Xylem sap from Actinidia chinensis: seasonal changes in composition. Ann Bot. 1983;51:823–833. [Google Scholar]

- Fromard L, Babin V, Fleurat-Lessard P, Fromont J-C, Serrano R, Bonnemain J-L. Control of vascular sap pH by the vessel-associated cells in woody species. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:913–918. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.3.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan T, Schurr U, Schulze E-D. Stomatal response to drying soil in relation to changes in the xylem sap composition of Helianthus annuus. I. The concentration of cations, anions, amino acids in, and pH of, the xylem sap. Plant Cell Environ. 1992;15:551–559. [Google Scholar]

- Hartung W. The site of action of abscisic acid at the guard cell plasmalemma of Valerianella locusta. Plant Cell Environ. 1983;6:427–428. [Google Scholar]

- Hartung W, Radin JW. Abscisic acid in the mesophyll apoplast and in the root xylem sap of water-stressed plants: the significance of pH gradients. Curr Top Plant Biochem Physiol. 1989;8:110–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann B, Kosegarten H. FITC-dextran for measuring apoplast pH and apoplastic pH gradients between various cell types in sunflower leaves. Physiol Plant. 1995;95:327–335. [Google Scholar]

- Imber D, Tal M. Phenotypic reversion of flacca, a wilty mutant of tomato, by abscisic acid. Science. 1970;169:592–593. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3945.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MB, Davies WJ, Else MA. Pressure-flow relationships, xylem solutes and root hydraulic conductance in flooded tomato plants. Ann Bot. 1996;77:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jones HG (1980) Interaction and integration of adaptive responses to water stress: the implications of an unpredictable environment. In NC Turner, PJ Kramer, eds, Adaptation of Plants to Water and High Temperature Stress. Wiley, New York, pp 353–365

- Kaiser WM, Hartung W. Uptake and release of abscisic acid by isolated photoautotrophic mesophyll cells, depending on pH gradients. Plant Physiol. 1981;68:202–206. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.1.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Satter RL. Effects of white, blue, red light and darkness on pH of the apoplast in the Samanea pulvinus. Planta. 1989;178:31–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00392524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marré MT, Albergoni FG, Moroni A, Marré E. Light-induced activation of electrogenic H+ extrusion and K+ uptake in Elodea densa depends on photosynthesis and is mediated by the plasma membrane H+ ATPase. J Exp Bot. 1989;40:343–352. [Google Scholar]

- Mengel K, Planker R, Hoffmann B. Relationship between leaf apoplast pH and iron chlorosis of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) J Plant Nutr. 1994;17:1053–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Parry AD, Neill SJ, Horgan R. Xanthoxin levels and metabolism in the wild-type and wilty mutants of tomato. Planta. 1988;173:397–404. doi: 10.1007/BF00401027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman MG, Wildes RA, Schaefer N, Wellfare D. Effect of azetidine 2-carboxylic acid on ion uptake and ion release to the xylem of excised barley roots. Plant Physiol. 1977;60:240–246. doi: 10.1104/pp.60.2.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA, Smith FA. Nitrogen assimilation and transport in vascular land plants in relation to intracellular pH regulation. Plant Physiol. 1976;76:415–431. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan PR, Newman IA, Arif I. Rapid calcium exchange for protons and potassium in cell walls of Chara. Plant Cell Environ. 1992;15:675–683. [Google Scholar]

- Sauter JJ, Ambrosius T. Changes in the partitioning of carbohydrates in the wood during the bud break in Betula pendula Roth. J Plant Physiol. 1986;124:31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Schurr U, Gollan T, Schulze E-D. Stomatal response to drying soil in relation to changes in the xylem sap composition of Helianthus annuus. II. Stomatal sensitivity to abscisic acid imported from the xylem sap. Plant Cell Environ. 1992;15:561–567. [Google Scholar]

- Schurr U, Schulze E-D. The concentration of xylem sap constituents in root exudate, and in sap from intact, transpiring castor bean plants (Ricinus communis L.) Plant Cell Environ. 1995;18:409–420. [Google Scholar]

- Schurr U, Schulze E-D. Effects of drought on nutrient and ABA transport in Ricinus communis. Plant Cell Environ. 1996;19:665–674. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz A, Wu WH, Tucker EB, Assmann SM. Inhibition of inward K+ channels and stomatal response by abscisic acid: an intracellular locus of phytohormone action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4019–4023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovik S, Hartung W. Compartmental distribution and redistribution of abscisic acid in intact leaves. II. Model analysis. Planta. 1992a;187:26–36. doi: 10.1007/BF00201620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovik S, Hartung W. Compartmental distribution and redistribution of abscisic acid in intact leaves. III. Analysis of the stress-signal chain. Planta. 1992b;187:37–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00201621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal M, Nevo Y. Abnormal stomatal behaviour and root resistance, and hormonal imbalance in three wilty mutants of tomato. Biochem Genet. 1973;8:291–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00486182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor IB, Linforth RST, Al-Naieb RJ, Bowman WR, Marples BA. The wilty tomato mutants flacca and sitiens are impaired in the oxidation of ABA-aldehyde to ABA. Plant Cell Environ. 1988;11:739–745. [Google Scholar]

- Tetlow IJ, Farrar JF. Apoplastic sugar concentration and pH in barley leaves infected with brown rust. J Exp Bot. 1993;44:929–936. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DS, Wilkinson S, Bacon MA, Davies WJ. Multiple signals and mechanisms that regulate leaf growth and stomatal behaviour during water deficit. Physiol Plant. 1997;100:303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich WR. Transport of nitrate and ammonium through plant membranes. In: Mengel K, Pilbeam DJ, editors. Nitrogen Metabolism in Plants. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S, Davies WJ. Xylem sap pH increase: a drought signal received at the apoplastic face of the guard cell that involves the suppression of saturable abscisic acid uptake by the epidermal symplast. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:559–573. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]