Abstract

Asian immigrant women have the lowest utilization of mental health services of any ethnic minority (Garland, Lau, Yeh & McCabe 2005). Because help seeking for distress occurs within social networks, we examined how social networks supported or disabled help seeking for Japanese sojourners living in the US. Unfortunately, most of the literature about Japanese social relationships focuses on men in organizational settings. This study used intensive ethnographic interviewing with 49 Japanese expatriate women to examine how social relationships influenced psychosocial distress and help seeking. We found that the women in these samples engaged in complex, highly regulated, complicated and obligatory relationships through their primary affiliation with other “company wives.” Like many immigrant women, increased traditional cultural norms (referred to in Japanese as ryoosai kenbo, or good wives and wise mothers), were expected from these modern women, and the enactment of these roles was enforced through scrutiny, gossip and the possibility of ostracism. Fears of scrutiny was described by the women as a primary barrier to their self-disclosure and ultimate help seeking. Understanding the social organization and support within the Japanese women's community is central to understanding how culturally specific social networks can both give support, as well as create social constraints to help seeking. Health oriented prevention programs must consider these social factors when evaluating the immigration stressors faced by these families.

Keywords: Japanese expatriates, Japanese women, Immigrant social organization, Japanese culture

Asian Americans are the fastest-growing ethnic group in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). The Asian population grew faster than the total U.S. population between 1990 and 2000 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001). Michigan has a large Japanese expatriate population due to the presence of the Japanese auto industry around Detroit. The majority of Japanese living there work in the automotive industry and related businesses, and they frequently bring their families with them. There are between 6000 and 8,000 Japanese families affiliated with this industry within Greater Detroit alone, with a population in 2008 of over 10,000 (Consulate General of Detroit, 2008), and the Japanese population in surrounding counties ranges from 4.2 to 8.3% of the total population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001).

Characteristics of the Asian population in general, and the Japanese sojourner population in particular, that may put them at risk for mental illness include separation from their extended families; family system and role relationship changes; lack of English language proficiency; employment problems; and ethnic discrimination. Asian immigrant women have gender-specific mental health risks. Gender-specific risks are patterns of psychosocial and cultural factors that place members of gender group at disproportionally vulnerability for a given illness. For Asian immigrants, female-specific risks include separations from extended families that dramatically affect their ability to perform role; changes in social roles related to social networks changes; economic dependency due to migration laws; employment problems including gender-based discrimination and occupational options; gender-based violence; income inequality even when compared with Asian males; social status and rank issues that are amplified in new social networks; and unremitting responsibility for the care of children, spouses and parents. (Ro, 2002; Ta & Hayes, 2009; Ta, Juon, Gielen, Steinwachs, & Duggan, 2008; Williams, 2002; World Health Organization, 2009). Studies have suggested that Asian cultures may promote role performance values and patterns that influence Asian immigrant women's help seeking. For example, Asian women may place the familial context as central to their self-evaluation, thereby being more likely to neglect their own health in order to fulfill their familial responsibilities. Gendered rules for proper Asian female behavior include the notion that women should sacrifice their personal needs for the good of their husbands and children, leading to a tendency to ignore or deny their own pain or symptoms so that their families' needs are properly addressed (Ro, 2002; Saint Arnault, 2002; 2004; 2009). We do not know the full impact of gendered views of roles and responsibilities vis-à-vis personal health, other family members, and community roles affect how women perceive and act upon their health.

While research about migrant and immigrant families and international sojourners in the social sciences has been prolific, they have primarily focused on the political and economic forces that shape their experiences. Very few studies have examined the experience of the wives of Japanese sojourners in America. Most research on spouses of expatriates interact primarily among their own social circles, and that these women felt that their lives were suspended until their return to their homeland (Flory, 1989). Some spouses report trying to stay happy for the success of their husbands, and frustration with the long hours and demands the experience placed on the husbands (DeCieri, Dowling, & Taylor, 1991). Research has shown that culture shapes distress experiences and their interpretation, and the importance of the interaction between distress, social networks and help-seeking (Groleau, Young, & Kirmayer, 2006; Guarnaccia, 1997b; Kirmayer, 1989; Kirmayer & Young, 1999; Mezzich et al., 1999).

Despite the overlapping risk factors and prevalence rates, there is convergent evidence that Asians underutilize mental health services regardless of the service type or their regional population density. The consequences of underutilization include high illness prevalence and high illness severity (Sue, 1999; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Studies examining factors that may cause this underutilization of mental health services have found the following; the tendency to endorse somatic rather than emotional and interpersonal problems (Kirmayer, 1986, 1991; Kirmayer, Dao, & Smith, 1998); stigmatization of psychiatric disorders and the desire to avoid shame and loss of face (Cheung & Lin, 1997; Gaines, 1998; Saint Arnault, 2002, 2009; Vogel, Wade, & Ascheman, 2009); differences in language, culture, and ethnicity that present barriers to health care access (Abe-Kim et al., 2007; Loue, 1998; Mezzich, Kleinman, Fabrega, & Parron, 1996; Sue, 1999); and a culturally-based lack of understanding of western-defined psychiatric disorders (Christensen, 2001; Groleau, et al., 2006; Guarnaccia, 1997a; Kirmayer, 1991; Lee, 2002; Mezzich, et al., 1999).

The cultural ideology of the group is important in understanding the social relations of Japanese people, but it contains a complex set of social rules based on the complementarity of seemingly opposing dynamics: consensus and solidarity on the one hand, and status differences within groups on the other. In addition, unconstrained relations are generally with those who are close or part of the uchi (Hendry, 1992), and more regulated or formal interactions are used when interacting with those outside of the known (soto). The meaning of the self, one's position within a group, and guidelines for behavior within any given group are referred to as situated meaning—meaning that is derived from a multitude of social situational factors (Bachnik, 1994). Therefore, harmonious interactions within a group require a person to assess each context and one's role within it. Social control in the form of gossip and ostracism may be used for those who foster conflict or indicate deviance are frowned upon, and may result in ostracism (Bestor, 1996; Johnson, 1995; Lebra, 1976; Saint Arnault, 2004; Smith, 1995).

The implications for harmonious group interactions are gender specific. In pre-WWII Japanese villages, like in many villages, other members of the village regulated women's behavior. The ideal for women in these villages was the role of ryoosai kenbo, or good wife and wise mother. Some authors have speculated that the urban community may also regulate women's propriety and role enactment, and that migrant women may also face an intensification of traditionalism (Bestor, 1996; Ishii-Kuntz, 1993; Mirdal, 1984; Morokvasic, 1984; Pedraza, 1991; Pessar, 1984; Sinke, 2006).

Social and cultural patterns have implications for mental health and help seeking. Herleman, Britt and Hashima examined the importance of the concept of Ibasho to understanding perceived stress for Japanese living abroad. Ibasho is a Japanese term that originally means “whereabouts” and connotes a place where a person feels acceptance, security, belonging, and/or coziness (Herleman, Britt, & Hashima, 2008). Ibasho accounted for unique variance in the prediction of general adjustment, personal adjustment, satisfaction, and depression beyond demographic control variables and social support. Ibasho interacted with stressors and significantly predicted perceived stress for expatriate spouses, helping us understand how feelings of home and community can be both a protective factor and a stressor. Saint Arnault also examined how culture can be understood as rules about closeness, distance, and reciprocity. Understanding these rules helped explain how the cultural nature of “social support” is not always supportive. She found that that emotional restraint was high in non-intimate social relationships, and this emotional restraint inhibited self-expression of distress (Saint Arnault, 2002). Taken together, this review demonstrates that social networks are shaped by cultural ideals and rules, which in turn affect stressors as well as help seeking for them. Because help seeking general begins within one's natural social world, we used intensive ethnographic interviewing to examine how social networks impacted women's roles, feelings of security and support, and help seeking for expatriate Japanese women.

Method

Research design and sample

This is a descriptive study that used two waves of intensive semi-structured ethnographic interviewing to examine how distress was perceived within the context of the social networks formed by the Japanese expatriate community, and how that influenced help seeking for spouses of Japanese international employees. A university Human Subjects Review Board approved the research for both waves prior to data collection.

This research reports the findings of interviews held with women at two time-points. The first wave was a sample of 25 women gathered using snowball sampling techniques in 1998. The second wave was a sample of 24 women was gathered using interval sampling with random start in 2007. The purpose of carrying out two study waves was to examine whether the trends found in the snowball sample would remain when a random sampling design was used. The women from the second wave were recruited from a community based sampling frame that included a medical clinic serving the Japanese community and Japanese women's groups in the community. The details of the second wave random sampling are as follows: we estimated the number of women possible to sample, divided that by the total sample number, and using the quotient as our sampling interval. Women whose names were randomly selected were sent a survey containing questions about their distress and help seeking (results reported elsewhere). The second wave interviews reported here were from a sub-sample of survey participants who agreed to be interviewed.

The women in both samples lived in single-family homes. The average age of the women in wave 1 and wave 2 was 36 and 39 years respectively, and the age ranges in both samples was 25 to 59 years old. The average length of time women had spent abroad in both samples was 6 years, and the range was from 1 to 14 years. About one quarter of the women in both samples had either no children or very young children, 40% had school-aged children, and the remainder had grown children living in Japan or going to college in the U.S.

All research materials and interaction with the participants was in Japanese by bilingual female Japanese research staff. Licensed counseling practitioners collected all data, and teams of bilingual Japanese staff with training in intercultural communication carried out all translations. The transcription and translation procedures are reported elsewhere (Saint Arnault & Shimabukuro, In Press; Saint Arnault & Fetters, In Press). However, our research team rotated materials so that at least two to three staff worked on any given interview document. One bilingual female research staff transcribed every interview verbatim, and a second bilingual translator translated the interview using both the transcription and the audiotaped interview to ensure accuracy. The resulting transcript had Japanese and English adjacent to each other for verification of accuracy and to enable ease of cross-referencing between languages. Finally, the accuracy of the transcription and the translation was reviewed by a third Japanese staff who was also the interviewer. All transcriptions and translations were completed with a detailed notation system that captured nuances of meaning and alternative translations. An example of the English text that includes the notations is:

Since I was a child, there weren't really many times I thought “I like my father and mother very much.” [YF: “I like my dad and mom very much” might mean “I love my father and mother,” but Japanese people don't use the word “love” to express their affection toward their parents.] … So we didn't have a betabeta-shita relationship at all [YF: “Betabeta-shita” means “affectionate” or “close” but in this sentence the word has a negative connotation].

For both waves, bilingual research staff made an initial phone contact and interviews were arranged at a location of the participant's choice. At the time of the interview, the participants were assured of their confidentiality both orally and in a written informational letter, and signed consent was obtained for audio-taping. The interviews were semi-structured ethnographic interviews developed by the primary author. The first wave interview was pilot tested with three Japanese women. The interview for the second wave was refined from the first wave interview, and was pilot tested with six Japanese women. The interviews were about two hours in length, and all were tape-recorded. The interviews began with discussions about daily life, including roles and responsibilities. Next, the women were invited to depict their social network on a piece of paper. The interview then discussed these drawings, focusing on the nature of the relationships, closeness, support, areas of tension, and help seeking. Next, the women were asked to discuss times when they felt they could confide in others, and times when they did not feel safe to confide.

Analysis. We used analytic ethnographic method to analyze the data (Lofland, 1995), and used Atlas ti software for analysis and data management (Muhr, 2006). The Japanese and the English materials were used for analysis; however, the English text was used during all team meetings. Because coding concerned the nuances and cultural meanings of the Japanese social life, all coding was discussed extensively in team meetings for accuracy of interpretation.

Analytic Ethnography (AE) was used as the analytic framework. AE retains the qualitative dimensions of concern in grounded theory, including the coding rigor as well as emergent analysis. However, unlike grounded theory, which relies on theoretical sampling and theoretical saturation, AE provided us with the ability to select a predefined sample. This was necessary for the second wave because we used random sampling to gather the sample. During analysis, the AE approach was used to examine the type, structure, process, cause and consequence, frequency, magnitude and agency of distress, social network dimensions, and the implications of these on help seeking.

Findings

Three major themes were consistent across both samples. The first theme was that the women engaged with other Japanese as their primary reference group. The second theme was that the Japanese reference group assigned a role called a “company wife” that had new rules and expectations. The third theme was that the Japanese reference group exerted a level of social control that caused distress and disabled help seeking. We also included analysis of a negative case, which were those women who chose not to engage with the Japanese reference group.

The Japanese as the primary reference group

Women compared their social relationships in Japan with those they had had as the wife of an expatriate. In Japan, while the company may have been recognized conceptually for its role in supporting the needs of the worker and the family, women stated that the company was not directly involved in the family life. One woman said it this way:

My husband works for a pretty big company. When I was in Japan…(my involvement with) the horizontal relationships within the company… really wasn't much of that. But, since I've been here, there are home parties, and … many occasions where we would have dinner together or do things together with my husband's colleagues and bosses…my relationships are more dense now.

However, for these Japanese sojourner wives living in the US, the company was the initial and primary reference group for them and their families. Another woman said:

Yes, (here, we) socialize as a family. When we lived in Japan, to be frank, well, things like my husband's (work) parties were just for him. After we came here, the family has become somewhat equal. But I'm bad at that…I don't like it at all.

All of the women in the interviews not only expected that the company would care for their instrumental needs, such as housing, but also expected that the company would address their emotional needs as well. Despite the geographical distance between the employee's homes, the other company employees described as neighbors or their community. One woman stated that:

…when I lived in Japan, I really never thought about things like my husband's company. It was completely another world or a different world, so I didn't know it at all. I didn't care at all, but after I came here, I kind of realized.

Another woman said “Ah, that's the situation (that now we are involved with the women from my husband's company)…It's difficult after all.” And, another woman said:

After I came here, even though it is said that there are many Japanese, it is still a few, and among them, I have more occasions to hear about the company and meet people like his supervisor and the supervisor's wife.

The relationships women had with the other members of the company depended, in part, on the position of her husband within the company, and the responsibilities his position conferred onto her.

Our relationship is also defined by our husbands' status. My husband is holding relatively higher status at work, and other wives know about him from their husbands. They have an image of me as a wife of higher-status person.

Moreover, the nature and frequency of these relationships also depended on the size of the company, because the more employees there were, the less direct responsibility any given wife might have with any other company spouse.

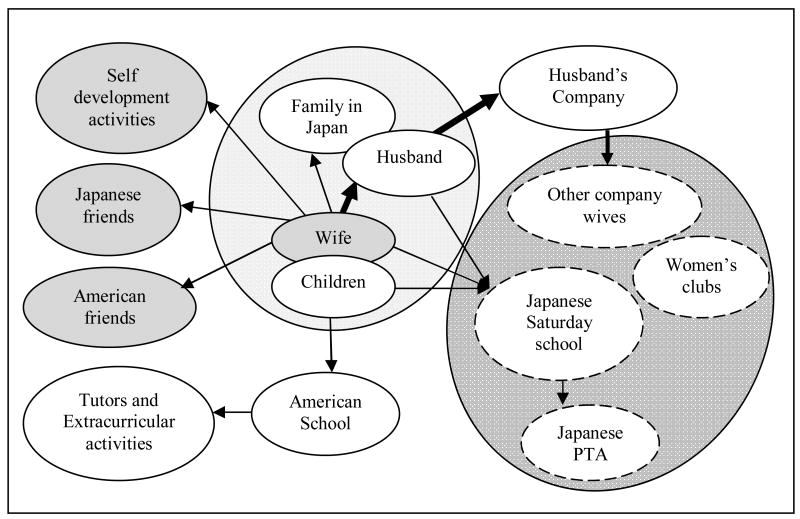

Figure 1 is a composite developed from the drawings made by women in the interviews to depict their social networks. One feature is the weak tie with the geographical neighborhood. Women only occasionally mentioned Americans friends or neighbors. Another common feature was the variety of self-development classes. Finally, many of the women interacted with other company wives.

Figure 1. Composite Social Network.

In general, the women in the interviews indicated that their social relationships in Japan were very different from those they had in America. If the women in Japan worked, they associated with others from their own workplace. However, in Japan, their personal social circles were segregated from each other. One respondent made the startling statement that: “Japan is more individualized (than America), isn't it? Because people in Japan don't act in a group so much” She is not referring to a lack of group-mindedness, but saying that, in Japan, she came and went as she pleased, making friends and socializing as she desired. The women's social circles rarely overlapped in Japan. In the US, however, women stated that they felt a pressure to join certain groups as illustrated in the following quote:

In Japan, a woman would be with someone that they liked. … (She) did not feel lonely because there are many Japanese people there. Here (in America) people become close to someone whose sense is relatively close to theirs … but they wonder if those relationships can become real friendships…here my associations are rather superficial.

This respondent was focusing on the long-term and mutual nature of relationships she had in Japan. She is contrasting those relationships with what she considered somewhat superficial relationships in the U.S. Another woman talks about the structure of the relationships through the company. We preserved the translation notations to demonstrate the complexity of the translation around this topic.

Here, we have Okusama-kai (SS: the Coalition of company wives). (CK: this sounds too serious…))((SS: I think it captures the sense of the purpose of the group)). My husband's company has organized a unit of company wives, and the wives take turns in various roles.

The role of a “company wife”

The responsibilities and roles of the “company wife” were generally new for the women, so that initially she did not understand them or know how to deal with them. As one woman said:

If we knew what would be expected of us (as company wives) in the beginning, we would have adjusted ourselves easily…However, we have to start from nothing (having never had this type of responsibility before), so it's harder to deal with the Japanese people than it is to live (in a foreign country).

This woman is saying that the relationship dynamics among the company wives and the Japanese communities as a whole were the biggest problem she faced when she came here. This is partly because there are relationship expectations that she has had little experience or skill in dealing with. For example, being a company wife carries with it a set of responsibilities to support and get along with the other company wives. In addition, company wives' behavior with each other directly affects the security of the family.

We asked the women in the interviews what factors affected their interactions with other Japanese women. Women indicated that status of a given woman's husband, her conferred status, was central to the way the other wives and how she defined her role. One woman answered:

If I were subordinate to somebody, I would have been able to be passive. But I was in a …(higher) position, and I had to raise everybody's spirits up. So I had to take a central role to invite people to join, propose the agenda, and encourage people to participate … I had to keep my sprit up all the time.

Another factor that was related to her role vis-à-vis the company was the character of the company itself; its “personality,” “culture” or “color.” This “company personality” affected the women because different companies were more or less concerned about the behavior of their employees' spouses. The concern for their behavior was communicated to the wives through their husbands, other wives (especially the boss' wives), or, in rare cases, directly to her through informational sessions held by the company.

When asked about their role as wives, the women indicated that it was their role to create a pleasant place for their husbands to live, and for their home to be clean and pleasant when their husbands' entertained guests. Proper role function included making their husbands' lunches, preparing good Japanese and American food, and attending or hosting company gatherings. A more subtle aspect of the role of the wife was that she was to get along with the other wives, and help them if necessary. The women reported that sometimes a pressure or “silent understanding” that they behave “as typical Japanese” characterized their relationships with the other wives. Being “typical” might mean attending the company wife functions. One interviewee, in responding to the question of her role, stated that it was not the role of a wife, but the role of a “good company wife” that she had learned to enact. She was candid about the scrutiny the other wives used to enforce the expectation that each woman's primary role was to support her husband, and thereby supporting the company itself.

The level of responsibility as a “company wife” increased as they lived in America longer. When the wives initially arrived, they were in a position to rely on the others for support and advice. Entry into this company circle allowed women to feel welcomed and supported in very specific ways. After a while, the women moved from being the recipient of support into positions in which they could provide help and support to others.

Women reported that their frequency of meeting with the other wives from their husband's company varied from monthly to three times per month. However, the frequency and type of interaction varied depending on an interaction between three factors—their life stage (a combination of their age and the age of their children), their conferred status and their feelings about the Japanese community. Some women spoke of being in charge of holding functions for the other company wives, other company gatherings and seasonal parties, showers, welcoming and farewell parties: “The aspect of helping each other as a family is strong…So my husband's friend is a friend, so to speak. I know his colleague and his wife.”

The Maintenance of Conformity

In Japan, the interviewed women reported that their behavior was directly overseen within the community where she lives. She was expected to behave respectfully with others she saw on the street, or she was expected to be at home caring for her children. The women described feeling “in the eyes” of the community, and that they carefully monitored their public displays in these settings. One interviewee described it this way:

I had a job when I was in Japan, and I think my life was restricted in terms of clothes, behaviors, and language. I worked for a university, and men had power there. In short, old male professors dominated, so I always watched my language with my superiors and wore clothes, not that I liked, but which made a good impression on others. Because people live closely in Japan, I think I have naturally acquired such skills to make a good impression on others such as greeting with a smile and not laughing with large mouth.

This woman is focusing on the way that those around her scrutinized her public behavior, especially those who were her superiors. She was also describing the necessity to develop certain social skills, such as speech patterns, or avoiding strong public displays of emotion. Some women described the need to “live quietly,” referring to the cultural tendency to avoid notice. These include context-appropriate speech patterns, dress, manner, and emotional display as indicated above. Behavior that might invite notice might include any behaviors that are not “typical Japanese behaviors.” One woman said: “When I said enryo(self restraint)…I mean I constrain myself because I cannot say all the things that I have in mind. I suspect that Japanese people might judge me for what I say.”

“Typical” behaviors include enacting her roles as a wife, mother and community member. In referring to her relationship with members of her community, another interviewee stated: “In Japan, people worry about the public eyes and neighbor's gossip (when they begin to go back to school, or begin a new affiliation).” Another said: “For instance, in the area where I lived in Japan, most of the mothers with middle-school children were working part-time. If I went to a college, my neighbors would think I was disgusting.” The translation of the word “disgusting” invited some discussion among the research team. The choice of this translation was deliberate. It is used here to convey the flavor of criticism and the sense of pulling away from the one who is not typical. It conveys, too, how powerfully motivating it can be for a woman to conform to the expectations of her. Another woman refers to this concern about what others think of her in this way:

When I was in Japan, my behaviors were greatly restrained in many ways by my neighbors. And, it was rather difficult to live without such restraints, because people would think me strange (if I didn't follow the rules), gossiping about what kind of person I am. Therefore, I had to be careful about maintaining good relations with my neighbors (as I do here in America).

In this way, in Japan, the communities of people around the woman, whether they were her employers, her school relationships or her neighborhood, were guardians of proper social behavior, which included the enactment of role expectations. For the Japanese sojourners, the guardians of these expectations became transferred to the primary Japanese reference group now that she was in the US.

One of the ways that the Japanese community exerts social control is the threat of gossip. The potential that one will become the object of gossip was powerfully motivating for the women. As we shall see, these fears of public scrutiny have implications for help seeking. For example, when a woman is under great stress, or experiencing distress, she may avoid the public eye. For example, one woman said:

My husband drops my daughter off at the pre-school in the morning lately. It became more and more difficult for me to drop her off in the morning, and I even find it difficult to step out of the house lately, and felt sick most of the time. Knowing my condition, my husband's supervisor's wife suggested I see a counselor, because my being sick all the time might interfere with my husband's work performance.

Another woman describes wanting to talk about her stress, but feeling unable to do so:

This might sound strange, but I realized that I could not really expose all my honne (true feelings). If I want to express my honne, I should tell my friends in Japan who are far away. You never know how things get around. So, (you need to keep relationships) superficial. Even if you get along, you don't really share your feelings. Well, especially about unhappy things. You do talk about the facts, of course. “So-and-so happened,” or something, but you don't talk about emotions. I'm afraid because you never know how things might get around.

One woman told a story about when she shared her feelings with a bad outcome, resolving not to do so in the future:

I shared my past experiences with a friend to deepen our friendship, but she took it from different point of view and told about my experience to people. I felt like I misjudged this person, because I didn't think she would do that. I thought I had good judgment as to whom I could share my secrets. But, it turned out not to be true, so I have learned not to trust other people easily because of this incident.

Some of the women attribute this issue of gossip to the small size of the community:

Yes, the community is small, so if I say something about somebody such as “So-and-so did this to me, and I didn't like it,” and she tells it to somebody else, I wouldn't be able to be here anymore.

However, others talk about how this is a phenomenon they had experienced before, and thought it would be different now that they were in America.

(Americans are) individualistic, (and they) don't care about other people's business and don't talk about them, and I had thought Japanese people (in America) wouldn't do so, either, but it's almost the opposite. But, they talk about others, (so if) I say something, it will be repeated somewhere. Therefore, I don't want to say it, so I don't.

Another woman said:

It was force of habit. Hanging around…Doing guchu-guchu guchu-guchu with other Japanese [YF: Doing guchu-guchu is slang meaning socializing in an unhealthy way, and may involve gossiping and unproductive venting].

A few of the women talked about being unable to break out of this social network because of limited English. For example, one woman wants to talk with her American friend: “But, of course, I have to speak English with her, so I can't really talk about complex issues like I do with Japanese friends.” However, mostly women focused on the combined concerns about gossip, the feeling of being unable to talk deeply to others, and the obligation to engage in a somewhat superficial social scene that created stress and isolation for many of the women. One woman put it very plainly, saying:“I socialized because I didn't want them to say anything”. Another, talking about wanting to avoid these encounters, tells that she goes because: “When it comes to the things about my husband's company, I can't ignore them or say no to them because I have to keep the face of my husband.”

However, there are costs to refusing. One woman said: “When you decline people's invitations again and again, people will eventually stop asking you to come. Ultimately, I would not be able to catch up with people's conversations, and I would feel isolated, or feel like I am being left out…I would feel even worse.” Another woman reflects on her situation. She goes out, but feels worse afterwards:

(Even though we were all Japanese people in a similar situation)…after getting together, I was a little sick of it. To be honest, when I saw them, we would hang out in the neighborhood, spent a little time in a gym, ended up eating a meal, and vented about many things, and after I would go home, I didn't feel good very at all.

One woman reflects on how she wants to deepen relationships, but that the community rotates too much, saying: “I think that if I were to see people more often, then I could trust them more. I have several longtime friends in Japan, but I don't have such friends here. I have only been here for two years. Even when I became friends with somebody, with whom I can get along well, they will go back to Japan soon.

Some of the women feel that there is nowhere to turn. This woman talks about needing to talk to someone, and knowing she can't talk to other women, thinks about reaching out to her parents in Japan:

(But) I can't do that. If I did, they would tell me that I suffer either because I am too weak, or I am not working hard enough. They would tell me that everybody else does just fine. I will feel even worse by telling them, so I can't tell my family about anything. My husband is only one person I can talk to. He would listen to me and understand my hardships, so I feel somewhat relieved after talking with my husband. So, he is the only one person I can talk to right now.

The negative case: Ambivalence related to engagement with the community

Women differed in terms of their feelings about the Japanese community. The decision about whether to “resist” or “conform” to the demands of the Japanese community was difficult for most of the women in the interviews. The conflict between these polarities existed for all of the women; however, they varied in terms of the way they chose to resolve the conflict. Factors they said affected their choices included their personality, the size and prestige of the company their husband worked for, and their personal goals for this American experience. Those women who chose to “conform” generally described their need to find a balance between independence and engagement. These women struggled with the need to maintain harmony and the need for self-fulfillment. They commented freely on issues such as gossip, complications between the company wives, or their feeling that the Japanese community confined their behavior. However, they participated in the Japanese community regularly. They seemed to expect and accept these features of a Japanese community, and saw their involvement in the Japanese community as an important part of their life in America. These women viewed those who avoided the Japanese community as being unable to get along, and questioned her priorities.

However, there were some women who actively engaged with Americans and other immigrants, and focused on self-fulfillment activities, such as education within the American system, including community education, Adult education, or college. These women tended to have English language skills, or felt comfortable trying to speak and learn the language, and seemed to have a good measure of self-confidence. These “resisting” women described themselves as seeking independence from the company wives group, and sometimes from the Japanese community as a whole. While they sometimes engaged in interactions with others company wives or crafts groups, they felt these were superficial, empty wastes of time. They described the Japanese community as too confining, stressful, obligatory, and/or complicated. They described wishing to go about their own business, enjoying a variety of people, and spontaneously engaging in the freedoms afforded being in America. These women were quite aware of their need for the Japanese community, and were grateful for their presence and support. They only felt it was too complicated, and kept a respectful distance.

Discussion

This research focused on a small but growing sector of the American populace: the international employee's family, and may not necessarily apply to immigrants. In addition, it is unclear how much of these finding might transfer to other Asian sojourners such as Koreans with the automotive industries. Careful community assessment would be necessary to determine this. Women across cultures have faced similar removal from their family and social networks for international work. According to the migration literature, migrant women generally face increased traditionalism, isolation from extended family and supportive kinship ties, and an increase in their dependency upon their husbands for support (Mirdal, 1984; Morokvasic, 1984; Pedraza, 1991; Pessar, 1984; Sinke, 2006). However, unlike many immigrants who settle with extended kin, these Japanese sojourners are temporary residents, relocating with only their nuclear families. These Japanese families also generally do not settle in ethnic enclaves because of specific policies of the Japanese companies. This separation from large concentrations of the same group inhibits replications of typical community relationships found in their own country.

In the US, these women engaged in numerous social obligations with relative strangers, occurring in overlapping social circles. This new social network carried with it increased social scrutiny and the threat of gossip or ostracism. While this settlement pattern allows the Japanese sojourner families the ability to have freedom from the direct impact of neighbors, they still experienced an increase in traditionalism. It is unknown whether sojourners for other types of companies such as fishing, microelectronics or banking would organize in the same ways.

It is interesting to examine this increased traditionalism sociologically. In contrast to research on some immigrant women, especially Christian, Catholic and Muslim women, it is noteworthy that the families in this Japanese community did not organize around religious institutions. The conservatism they described was related to sociocultural rules for propriety, not religious ones. The allegiance of many community members is to the parent companies and to Japan, not to higher ideals rooted in religious mores.

One of the vehicles for the increase in the traditional expectations was the role as the company wife. Because of cultural factors like group orientation, many Japanese women chose to interact in what they perceive as a “small community” that demanded conformity and used social sanctions like gossip to enforce expectations. Social service, health care providers, and educators often mistake restricted interactions with others from the same ethnic or linguistic groups as “social support.” That is, if people prefer to confine their help seeking to their community or their family, therefore they are living in a supportive environment. This study illustrates that interactions confined to one community may be enforced by conservative trends. This confinement to the Japanese community is complicated at best, and a primary source of social pressure at the worst. In the case of these Japanese women, on the surface, when one sees women interacting with each other at restaurants, we assume that all is friendly, casual and enjoyable. What is not visible is the considerable pressure to conform, and to interact harmoniously. If the Japanese women are expected to carefully enact the role of the company wife for the sake of the wellbeing of the family, and if this includes primarily social propriety, then active, honest help seeking from outside of the Japanese community will be inhibited. Indeed, for many women, an honest disclosure of the hardships of their lives might reveal a failure of the women to care for herself and her family.

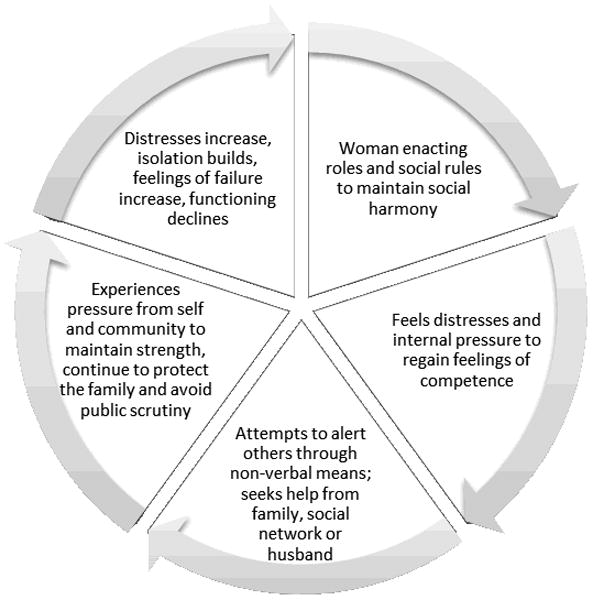

The Japanese are hardworking people who value self-reliance and personal competence. From the view of the outsider, these Japanese women have money, elegance, and freedom from work life responsibilities. The women in these interviews prided themselves on maintaining a beautiful home, creating beautiful meals, and maintaining their elegance in public. However, there is a social and emotional cost for this. Figure depicts a model of a help seeking trajectory that emerges from these findings.

The literature about Asian Americans is beginning to address the “myth of the model minority (Chen & Yoo, 2010; Chou & Feagin, 2008; Hayashi, 2003; Li & Wang, 2008; Yoo, 2010).” While this term has referred to the myth that Asians excel in math and science, its contemporary use as a stereotype has implications for health and mental health. As we have seen in these examples, the public face that the Japanese (and other Asians) sometimes show is related to cultural norms, rules, and roles. Interested community service practitioners must create the space and permission to allow the women to speak freely about their needs. We believe that translators should not be drawn from the community that the women live in, or this will inhibit her ability or willingness to speak freely. We also caution service providers to recognize the pressures these wives face to create safe and harmonious homes for their husbands and children in an unfamiliar environment with complicated support networks. Finally, we believe that more research should be done to examine how these patterns are similar or different for other Asian immigrants.

Figure 2. Cycle of thwarted help seeking.

Acknowledgments

Wave 2 of this research was supported by the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health and the National Institute of Mental Health (MH071307).

Contributor Information

Denise Saint Arnault, Michigan State University College of Nursing.

Deborah J. Roles, Michigan State University, College of Nursing, B510-B West Fee Hall, East Lansing, Michigan 48824.

References

- Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, Zane N, Sue S, Spencer MS, Alegría M. Use of Mental Health–Related Services Among Immigrant and US-Born Asian Americans: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):91–98. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachnik J. Introduction: Uchi/Soto: Challenging our concept of self, social order and language. In: Bachnik JM, Quinn C, editors. Situated meaning: Inside and outside in Japan: self, society and language. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1994. pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bestor T. Forging tradition:social life and identity in a Tokyo neighborhood. In: Gmelch G, Zenner WP, editors. Urban life: Reading in Urban Anthropology. 2nd. Prospenct Heights: Waveland Press, Inc.; 1996. pp. 524–547. [Google Scholar]

- Chen EWC, Yoo GJ. Encyclopedia of Asian American Issues Today. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung F, Lin KM. Neurasthenia, depression and somatoform disorder in a Chinese-Vietnamese woman migrant. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 1997;21(2):247–258. doi: 10.1023/a:1005340905397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou RS, Feagin JR. The Myth of the Model Minority: Asian Americans Facing Racism. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M. Diagnostic criteria in clinical settings: DSM-IV and cultural competence. American Indian & Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2001;10(2):52–66. doi: 10.5820/aian.1002.2001.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCieri H, Dowling P, Taylor K. The psychological impact of expatriate relacation on Partners. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 1991;2(3):377–414. [Google Scholar]

- Flory M. Unpublished Dissertation. Columbia University; New York: 1989. More Japanese than Japan: Adaptation and social network formation among the wives of Japanese businessmen in Bergen county, New Jersey. [Google Scholar]

- Gaines AD. Mental illness and immigration. In: Loue S, editor. Handbook of immigrant health. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 407–421. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Lau AS, Yeh M, McCabe KM. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Utilization of Mental Health Services Among High-Risk Youths. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(7):1336–1343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groleau D, Young A, Kirmayer LJ. The McGill Illness Narrative Interview (MINI): An Interview Schedule to Elicit Meanings and Modes of Reasoning Related to Illness Experience. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2006;43(4):671–691. doi: 10.1177/1363461506070796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia PJ. A cross-cultural perspective on anxiety disorders. In: Friedman S, editor. Cultural issues in the treatment of anxiety. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1997a. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia PJ. Ethnicity, immigration, and psychopathology. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1997b. Social stress and psychological distress among Latinos in the United States; pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi MC. Far from Home: Shattering the Myth of the Model Minority. Wyomissing, PA: Tapestry Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry J. Individualism and Individuation: entry into a social world. In: Goodman R, Refsing K, editors. Ideology and practice in modern Japan. NY: Routledge; 1992. pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Herleman HA, Britt TW, Hashima PY. Ibasho and the adjustment, satisfaction, and well-being of expatriate spouses. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2008;32(3):282–299. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. Dependency and Japanese socialization. NY: New York University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ. Illness behavior: A multidisciplinary model. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1986. Somatization and the social construction of illness experience; pp. 111–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ. Cultural variations in the response to psychiatric disorders and emotional distress. Social Science & Medicine. 1989;29(3):327–339. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ. The place of culture in psychiatric nosology: Taijin kyofusho and DSM-III--R. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1991;179(1):19–28. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199101000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Dao THT, Smith A. Clinical methods in transcultural psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1998. Somatization and psychologization: Understanding cultural idioms of distress; pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Young A. Culture and context in the evolutionary concept of mental disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108(3):446–452. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.3.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebra T. Japanese pattern of behavior. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. Socio-cultural and global health perspectives for the development of future psychiatric diagnostic systems. Psychopathology. 2002;35(2-3):152–157. doi: 10.1159/000065136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Wang L. Model minority myth revisited: an interdisciplinary approach to demystifying Asian American educational experiences. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lofland J. Analytic ethnography: Features, failings, and futures. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 1995;24:30–67. [Google Scholar]

- Loue S, editor. Handbook of immigrant health. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzich JE, Kirmayer LJ, Kleinman A, Fabrega H, Jr, Parron DL, Good BJ, Manson SM. The place of culture in DSM-IV. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1999;187(18):457–464. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199908000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzich JE, Kleinman A, Fabrega H Jr, Parron DL, editors. Culture and psychiatric diagnosis: A DSM-IV perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mirdal G. Stress and distress in migration: problems and resources of Turkish women in Denmark. International migration Review. 1984;18:984–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morokvasic M. Birds of passage are also women. International Migration Review. 1984;18:886–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhr T. Atlas.ti (Version 5.0) Berlin: Scientific Software Development; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza S. Women and Migration: The Social Consequences of Gender. Annual Review of Sociology. 1991;17:303–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.17.080191.001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessar P. The linkage between the household and workplace of Dominican women in the U.S. International Migration Review. 1984;18:1188–1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro M. Moving Forward: Addressing the Health of Asian American and Pacific Islander Women. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):516–519. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM. Help-seeking and social support in Japan Sojourners. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;24(3):295–306. doi: 10.1177/01939450222045914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM. The Japanese. In: Ember CR, Ember M, editors. Encyclopedia of Medical Anthropology. Vol. 1. Yale University; 2004. pp. 765–776. [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM. Cultural Determinants of Help Seeking. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2009;23(4):259–278. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.23.4.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, Shimabukuro S. Clinical Ethnographic Interview: A user friendly assessment of culture and psychological distress. Transcultural Psychiatry. doi: 10.1177/1363461511425877. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, Fetters MD. RO1 Funding for Mixed Methods Research: Lessons learned from the Mixed-Method Analysis of Japanese Depression Project. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. doi: 10.1177/1558689811416481. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinke SM. Gender and Migration: Historical Perspectives. The International Migration Review. 2006;40(1):82–103. [Google Scholar]

- Smith HW. The myth of Japanese homogeneity: Social-ecological diversity in education and socialization. St. Louis, MO: University of Misouri; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S. Asian American Mental Health. In: Lonner W, Dinnel D, editors. Merging past, present, and future in cross-cultural psychology. Lisse, Netherlands: Swets and Zeitlinger; 1999. pp. 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ta VM, Hayes D. Racial Differences in the Association Between Partner Abuse and Barriers to Prenatal Health Care Among Asian and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander Women. Maternal Child Health Journal. 2010;14(3):350–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ta VM, Juon Hs, Gielen AC, Steinwachs D, Duggan A. Disparities in Use of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services by Asian and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander Women. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2008;35(1):20–36. doi: 10.1007/s11414-007-9078-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. The Asian and Pacific Islander Population in the United States: March 2000 (Update) (PPL-146. 2001 Retrieved August 21, 2004, from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/race/api.html.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race and Ethnicity--A supplement to Mental Health: A report to the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DL, Wade NG, Ascheman PL. Measuring perceptions of stigmatization by others for seeking psychological help: reliability and validity of a mew stigma scale with college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56(2):301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Racial/ethnic variations in women's health: the social embeddedness of health. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):588–597. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Women and health: today's evidence, tomorrow's agends. Geneva: Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo H. A preliminary report on a new measure: internalization of the Model Minority Myth Measure (IM-4) and its psychological correlates among Asian American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57(1):114–127. doi: 10.1037/a0017871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]