Abstract

Background

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a frequent cause of death among elderly. Patients affected by lower extremity peripheral arterial disease (LE-PAD) seem to be particularly at high risk for AAA. We aimed this study at assessing the prevalence and the clinical predictors of the presence of AAA in a homogeneous cohort of LE-PAD patients affected by intermittent claudication.

Methods

We performed an abdominal ultrasound in 213 consecutive patients with documented LE-PAD (ankle/brachial index ≤0.90) attending our outpatient clinic for intermittent claudication. For each patient we registered cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities, and measured neutrophil count.

Results

The ultrasound was inconclusive in 3 patients (1.4%), thus 210 patients (169 males, 41 females, mean age 65.9 ± 9.8 yr) entered the study. Overall, AAA was present in 19 patients (9.0%), with a not significant higher prevalence in men than in women (10.1% vs 4.9%, p = 0.300). Patients with AAA were older (71.2 ± 7.0 vs 65.4 ± 9.9 years, p = 0.015), were more likely to have hypertension (94.7% vs 71.2%, p = 0.027), and greater neutrophil count (5.5 [4.5 – 6.2] vs 4.1 [3.2 – 5.5] x103/μL, p = 0.010). Importantly, the c-statistic for neutrophil count (0.73, 95% CI 0.60 – 0.86, p =0.010) was higher than that for age (0.67, CI 0.56–0.78, p = 0.017). The prevalence of AAA in claudicant patients with a neutrophil count ≥ 5.1 x103/μL (cut-off identified at ROC analysis) was as high as 29.0%.

Conclusions

Prevalence of AAA in claudicant patients is much higher than that reported in the general population. Ultrasound screening should be considered in these patients, especially in those with an elevated neutrophil count.

Introduction

Systemic atherosclerosis represents the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the western countries [1-3], with increased prevalence in the elderly population [4,5]. The atherosclerotic disease may involved different part of vascular tree, in particular coronary arteries, carotid arteries and peripheral arteries [6,7] .

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a frequent cause of death in the elderly and its incidence has increased during last decades because of the increasing life-expectancy and the development of easy and low-cost diagnostic tools like ultrasound [5,8-12]. The rising incidence of AAA and the severe prognosis in case of rupture with a mortality rate that can be as high as 90% [13] call for early identification and elective repair. However, opposing views have been published on the importance of ultrasound screening for AAA and there is still debate on the high-risk populations who need to be screened [14,15].

Lower extremity peripheral arterial disease (LE-PAD), one of the main expressions of atherosclerosis, affects about 27 million people in Europe and the United States [16] and is associated with a high risk of developing fatal and non-fatal ischemic cardiovascular events [2,17-19]. Patients affected by LE-PAD seem to be at particularly high risk for AAA development [20-22]. Accordingly, we aimed this study at assessing the prevalence and the clinical predictors of the presence of AAA in a homogeneous cohort of LE-PAD patients affected by intermittent claudication, the most frequent clinical expression of LE-PAD.

Methods

We performed an abdominal ultrasound in 213 consecutive patients with documented LE-PAD attending our outpatient complaining intermittent claudication. Using an Image Point Hx ultrasound system (Hewlett Packard) and a 3.0 MHz transducer, we measured in each patient both antero-posterior and transverse outer diameters at the largest portion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta. AAA was defined by an infrarenal abdominal aorta diameter ≥ 3 cm [23]. Infrarenal abdominal aortas 2.6 to 2.9 cm were defined ectatic.

The diagnosis of PAD was based on the presence of an ankle brachial index (ABI) ≤ 0.90. ABI was measured after participants had rested supine for 5 minutes. The systolic blood pressure in both brachial arteries, and the ankle systolic blood pressure in the right and left posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis arteries were measured using a Doppler probe. The ABI for each leg was then determined using the higher of the two readings from either the posterior tibial or dorsalis pedis arteries, and the higher of the two brachial readings. The lower ABI of the two legs was used for diagnostic purposes.

In each patient, clinical history and risk factors were assessed. Smokers included current and former smokers. Hypertension was diagnosed if systolic arterial pressure exceeded 140 mmHg and/or diastolic arterial pressure exceeded 90 mmHg, or if the patient used antihypertensive drugs. Hypercholesterolemia was diagnosed if plasma total cholesterol exceeded 200 mg/dL, plasma low-density lipoprotein cholesterol exceeded 130 mg/dL, or if the patient used lipid-lowering drugs because of a history of hypercholesterolemia. Diabetes mellitus was diagnosed if plasma fasting glucose exceeded 126 mg/dL or if the patient used hypoglycaemic agents. A history of coronary artery disease, previous myocardial infarction, or ischemic stroke was documented by hospital records. All patients underwent ultrasound examination of carotid arteries.

All participants gave written informed consent to the study, which was approved by our institutional Ethics Committee.

Blood samples and laboratory assay

Blood was drawn from an antecubital vein using a 19-gauge needle in a Vacutainer system (Becton-Dickson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Neutrophil count was measured with the Bayer H*2 hematology analyzer (Bayer Diagnostic Division, Tarrytown, NY).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 12.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentage or mean ± SD, with the exception of neutrophil count, which was expressed as median and inter-quartile range because of their skewed distribution. Comparisons were made by t-test for unpaired samples, χ2 test, or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. For continuous variables, receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to identify the threshold levels that provided the best cut-off for the prediction of the presence AAA. Correlations between continuous variables were evaluated by Spearman analysis.

All statistical tests were two-sided. For all tests, a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

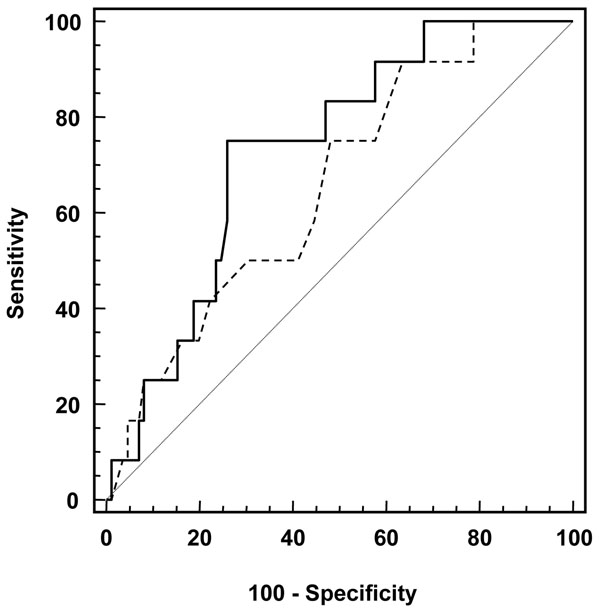

The ultrasound was inconclusive in 3 patients (1.4%), thus 210 patients (169 males, 41 females, mean age 65.9 ± 9.8 yr) completed the study. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the study population. Overall, AAA was present in 19 patients (9.0%), with a not significant higher prevalence in men than in women (10.1% vs 4.9%, p = 0.300). Furthermore, patients with AAA were older (71.2 ± 7.0 vs 65.4 ± 9.9 years, p = 0.015), were more likely to have hypertension (94.7% vs 71.2%, p = 0.027), and greater neutrophil count (5.5 [4.5 – 6.2] vs 4.1 [3.2 – 5.5] x103/μL, p = 0.010) (Table 2). The prevalence progressively increased with age (p for trend = 0.013), with a maximum of 15.8% in over 75-year-subjects (Table 3). Of note, in our population we observed a higher prevalence of carotid stenosis >50% in claudicant patients with AAA, although not significant (47.4 vs 29.3%, p = 0.105). No relationship was found between the ankle/brachial index and the presence of AAA. For continuous variables, which are associated to the presence of AAA at univariate analysis (i.e. age and neutrophil count), ROC curve analysis was performed to evaluate the best cut-offs to predict the presence of the disease (Figure 1). The best cut-offs were ≥ 66 years for age and ≥ 5.1 x103/μL for neutrophil count. Importantly, the c-statistic for neutrophil count (0.73, 95% CI 0.60 – 0.86, p = 0.010) was higher than that for age (0.67, CI 0.56–0.78, p = 0.017) (Figure 1). In our population the prevalence of AAA in claudicant patients with a neutrophil count ≥ 5.1 x103/μL (cut-off identified at ROC analysis) was as high as 29.0%. Of note, Spearman analysis showed that neutrophil count and age are not correlated (ρ = -0.123, p = 0.230).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (n=210)

| Number | Percentage or mean (SD) or median [25th-75th percentiles] | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.9 (9.8) | |

| Males | 169 | 80.5 |

| Height (cm) | 167.4 (7.5) | |

| Weight (Kg) | 73.9 (11.7) | |

| Risk factors | ||

| Smoking | 188 | 89.5 |

| Hypertension | 154 | 73.3 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 137 | 65.2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 75 | 35.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.2 (3.4) | |

| WC (cm) | 97.6 (9.4) | |

| Metabolic syndrome | 96 | 45.7 |

| Comorbidity | ||

| CAD | 106 | 50.5 |

| Previous MI | 76 | 36.2 |

| Previous stroke | 8 | 3.8 |

| Medications | ||

| Antiplatelets | 191 | 91.0 |

| Beta blockers | 47 | 22.4 |

| ACE-inhibitors | 104 | 49.5 |

| Statins | 130 | 61.9 |

| Carotid status | ||

| Carotid stenosis >50% | 65 | 31 |

| LE-PAD severity | ||

| Bilateral LE-PAD | 131 | 62.4 |

| ABI | 0.69 (0.22) | |

| Aortic features | ||

| Aortic diameter (mm) | 20.7 (6.8) | |

| Ectatic aorta | 13 | 6.2 |

| AAA | 19 | 9.0 |

| Inflammatory status | ||

| Neutrophil count (x103/μL) | 4.4 [3.3-5.7] |

SD = standard deviation; BMI = body mass index; WC = waist circumference; CAD = coronary artery disease; MI = myocardial infarction; ACE = angiotensin converting enzyme; LE-PAD = lower extremity-peripheral arterial disease; ABI = ankle/brachial index; AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Table 2.

Characteristics of claudicants according to the presence or absence of AAA.

| AAA | No AAA | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 19) | (n = 191) | ||

| Age (years) | 71.2 ± 7.0 | 65.4 ± 9.9 | 0.015 |

| Age ≥ 65 years | 16 (84.2) | 110 (57.6) | 0.024 |

| Males | 17 (89.5) | 152 (79.6) | 0.300 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Smoking | 18 (94.7) | 170 (89.0) | 0.437 |

| Hypertension | 18 (94.7) | 136 (71.2) | 0.027 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 15 (78.9) | 122 (63.9) | 0.188 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 4 (21.1) | 71 (37.2) | 0.162 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.5 ± 3.7 | 26.2 ± 3.4 | 0.742 |

| WC (cm) | 96.7 ± 9.6 | 97.7 ± 9.4 | 0.708 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 9 (47.4) | 87 (45.5) | 0.879 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| CAD | 10 (52.6) | 96 (50.3) | 0.844 |

| Previous MI | 5 (26.3) | 71 (37.2) | 0.348 |

| Previous stroke | 1 (5.2) | 7 (3.7) | 0.729 |

| Medications | |||

| Antiplatelets | 18 (94.7) | 173 (90.6) | 0.547 |

| Beta blockers | 2 (10.5) | 45 (23.6) | 0.194 |

| ACE-inhibitors | 11 (57.9) | 93 (48.7) | 0.444 |

| Statins | 10 (52.6) | 120 (62.8) | 0.383 |

| Carotid status | |||

| Carotid stenosis >50% | 9 (47.4) | 56 (29.3) | 0.105 |

| LE-PAD severity | |||

| Bilateral LE-PAD | 13 (68.4) | 118 (61.8) | 0.569 |

| ABI | 0.64 ± 0.11 | 0.69 ± 0.23 | 0.315 |

| Inflammatory status | |||

| Neutrophil count (x103/μL) | 5.5 [4.5 – 6.2] | 4.1 [3.2 – 5.5] | 0.010 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD or median [interquartile range].

AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm; BMI = body mass index; WC = waist circumference; CAD = coronary artery disease; MI = myocardial infarction; ACE = angiotensin converting enzyme; LE-PAD = lower extremity-peripheral arterial disease; ABI = ankle/brachial index; SD = standard deviation.

Table 3.

Distribution of AAA by age.

| Total | AAA | Prevalence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age < 55 years | 25 | 0 | 0% |

| Age 55 – 64 years | 59 | 3 | 5.1% |

| Age 65 – 74 years | 88 | 10 | 11.4% |

| Age ≥ 75 years | 38 | 6 | 15.8% |

p for trend = 0.013

Figure 1.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that prevalence of AAA in claudicant patients is much higher than that reported in the general population, with the highest clinical predictors being advanced age and an elevated inflammatory status.

To decrease the number of deaths from ruptured AAA, early detection by screening subjects at high risk is needed. Physical examination is not effective in identifying the presence of an AAA, while abdominal ultrasound is an accurate test to detect the presence of this life-threatening disease [23]. Elderly males are those who show the highest prevalence of the disease in the general population. Indeed there is evidence that screening programs involving males with > 65 years are cost-effective [14,24,25]. The strong association with age has been confirmed also in our population of claudicant patients. Indeed, we observed that the prevalence of AAA dramatically increases after 65 years (optimal cut-off identified at ROC analysis being ≥ 66 years) and no AAA was found in patients younger than 55 years of age. Thus age cut-off to initiate screening for AAA in patients with intermittent claudication seems to be the same than in general population. These results might suggest that performing an abdominal ultrasound in all claudicant patients may not be advisable. However, in our study, we found that an elevated inflammatory status, evaluated by neutrophil count, is a powerful predictor of the presence of AAA in patients with intermittent claudication, and that the neutrophil count did not correlate with age. Initiating the screening in patients ≥ 65 years with intermittent claudication might consequently lead to miss some diagnosis of AAA, and therefore in claudicant patients with an elevated inflammatory status the ultrasound screening should be performed irrespective of age. At this regard, pathophysiological studies are needed to evaluate whether the increased inflammation observed in our population of intermittent claudication patients affected by AAA is a cause or a consequence of the presence of AAA [19,26,27].

Conclusions

The high prevalence of AAA among patients affected by intermittent claudication makes them a suitable target population for AAA screening. In our opinion ultrasound screening should be considered in these patients, especially in those with an elevated neutrophil count. However, further studies are warranted to elucidate if screening all patients with intermittent claudication for of this life-threatening condition is cost-effective.

List of abbreviations

LE-PAD: Lower Extremity Peripheral Arterial Disease; AAA: Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm; ABI: ankle/brachial index.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GG, EL, CR, GDR, LB, AS, CP, LC, GGS, FS, AC, AS: conception and design, interpretation of data, given final approval of the version to be published, BA, BT: critical revision, interpretation of data, given final approval of the version to be published, GE: conception and design, critical revision, given final approval of the version to be published.

Contributor Information

Giuseppe Giugliano, Email: a.giugliano@inwind.it.

Eugenio Laurenzano, Email: eugeniolaurenzano82@katamail.com.

Carlo Rengo, Email: carlo.rengo@unina.it.

Giovanna De Rosa, Email: giovannaderosa@libero.it.

Linda Brevetti, Email: lindabrevetti@alice.it.

Anna Sannino, Email: anna.sannino@email.it.

Cinzia Perrino, Email: perrino@unina.it.

Lorenzo Chiariotti, Email: chiariot@unina.it.

Gabriele Giacomo Schiattarella, Email: gabriele.schiattarella@email.it.

Federica Serino, Email: fed.serino@gmail.com.

Marco Ferrone, Email: marco.ferrone1@gmail.com.

Fernando Scudiero, Email: fernando.scudiero@hotmail.it.

Andreina Carbone, Email: andr.carbone@gmail.com.

Antonio Sorropago, Email: a.sorropago@live.it.

Bruno Amato, Email: bramato@unina.it.

Bruno Trimarco, Email: bruno.trimarco@unina.it.

Giovanni Esposito, Email: espogiov@unina.it.

Acknowledgements

This article has been published as part of BMC Surgery Volume 12 Supplement 1, 2012: Selected articles from the XXV National Congress of the Italian Society of Geriatric Surgery. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcsurg/supplements/12/S1.

References

- Morrow DA, Braunwald E, Bonaca MP, Ameriso SF, Dalby AJ, Fish MP, Fox KA, Lipka LJ, Liu X, Nicolau JC. et al. Vorapaxar in the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:1404–1413. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giugliano G, Di Serafino L, Perrino C, Schiano V, Laurenzano E, Cassese S, De Laurentis M, Schiattarella GG, Brevetti L, Sannino A, Effects of successful percutaneous lower extremity revascularization on cardiovascular outcome in patients with peripheral arterial disease. International journal of cardiology. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cassese S, Esposito G, Mauro C, Varbella F, Carraturo A, Montinaro A, Cirillo P, Galasso G, Rapacciuolo A, Piscione F. MGUard versus bAre-metal stents plus manual thRombectomy in ST-elevation myocarDial infarction pAtieNts-(GUARDIAN) trial: study design and rationale. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions : official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2012;79:1118–1126. doi: 10.1002/ccd.23405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contaldi C, Losi MA, Rapacciuolo A, Prastaro M, Lombardi R, Parisi V, Parrella LS, Di Nardo C, Giamundo A, Puglia R. et al. Percutaneous treatment of patients with heart diseases: selection, guidance and follow-up. A review. Cardiovascular ultrasound. 2012;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiano V, Sirico G, Giugliano G, Laurenzano E, Brevetti L, Perrino C, Brevetti G, Esposito G. Femoral plaque echogenicity and cardiovascular risk in claudicants. JACC Cardiovascular imaging. 2012;5:348–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannacio V, Di Tommaso L, De Amicis V, Musumeci F, Stassano P. Serial evaluation of flow in single or arterial Y-grafts to the left coronary artery. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2011;92:1712–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.05.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato B, Markabaoui AK, Piscitelli V, Mastrobuoni G, Persico F, Iuliano G, Masone S, Persico G. Carotid endarterectomy under local anesthesia in elderly: is it worthwhile? Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis. 2005;76(Suppl 1):64–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornuz J, Sidoti C Pinto, Tevaearai H, Egger M. Risk factors for asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm: systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based screening studies. Eur J Public Health. 2004;14:343–349. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/14.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw JJ, Shaw E, Whyman MR, Poskitt KR, Heather BP. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms in men. BMJ. 2004;328:1122–1124. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7448.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Murphy WR, Olin JW, Puschett JB. et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation. 2006;113:e463–654. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino C, Scudiero L, Petretta MP, Schiattarella GG, De Laurentis M, Ilardi F, Magliulo F, Carotenuto G, Esposito G. Total occlusion of the abdominal aorta in a patient with renal failure and refractory hypertension: a case report. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2011;76:43–46. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2011.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciatore F, Abete P, Maggi S, Luchetti G, Calabrese C, Viati L, Leosco D, Ferrara N, Vitale DF, Rengo F. Disability and 6-year mortality in elderly population. Role of visual impairment. Aging clinical and experimental research. 2004;16:382–388. doi: 10.1007/BF03324568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prance SE, Wilson YG, Cosgrove CM, Walker AJ, Wilkins DC, Ashley S. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: selecting patients for surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;17:129–132. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.1998.0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergqvist D, Bjorck M, Wanhainen A. Abdominal aortic aneurysm--to screen or not to screen. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G, Franzone A, Cassese S, Schiattarella GG, Capretti G, Pironti G, Di Serafino L, Perrino C, Piscione F, Chiariello M. Endovascular repair for isolated iliac artery aneurysms: case report and review of the current literature. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2009;10:861–865. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e32832e1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitz JI, Byrne J, Clagett GP, Farkouh ME, Porter JM, Sackett DL, Strandness DE Jr., Taylor LM. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic arterial insufficiency of the lower extremities: a critical review. Circulation. 1996;94:3026–3049. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.94.11.3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer WT, Hoes AW, Rutgers D, Bots ML, Hofman A, Grobbee DE. Peripheral arterial disease in the elderly: The Rotterdam Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:185–192. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.18.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, Regensteiner JG, Creager MA, Olin JW, Krook SH, Hunninghake DB, Comerota AJ, Walsh ME. et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:1317–1324. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brevetti G, Giugliano G, Brevetti L, Hiatt WR. Inflammation in peripheral artery disease. Circulation. pp. 1862–1875. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Galland RB, Simmons MJ, Torrie EP. Prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients with occlusive peripheral vascular disease. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1259–1260. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800781036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano M, Mainenti PP, Imbriaco M, Amato B, Markabaoui K, Tamburrini O, Salvatore M. Multidetector row CT angiography of the abdominal aorta and lower extremities in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease: diagnostic accuracy and interobserver agreement. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50:303–308. doi: 10.1016/S0720-048X(03)00118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano M, Amato B, Markabaoui K, Tamburrini O, Salvatore M. Follow-up of patients with previous vascular interventions: role of multidetector row computed tomographic angiography of the abdominal aorta and lower extremities. The Journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2004;45:89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a best-evidence systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:203–211. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-3-200502010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato B, Iuliano GP, Markabauoi AK, Piscitelli V, Masone S, Compagna R, Esposito G, Piscione F. Endovascular procedures in critical leg ischemia of elderly patients. Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis. 2005;76(Suppl 1):11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasso G, Piscione F, Furbatto F, Leosco D, Pierri A, Rosa RD, Cirillo P, Rapacciuolo A, Esposito G, Chiariello M. Abciximab in elderly with acute coronary syndrome invasively treated: effect on outcome. International journal of cardiology. 2008;130:380–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G, Perrino C, Schiattarella GG, Belardo L, di Pietro E, Franzone A, Capretti G, Gargiulo G, Pironti G, Cannavo A. et al. Induction of mitogen-activated protein kinases is proportional to the amount of pressure overload. Hypertension. 2010;55:137–143. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.135467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giugliano G, Brevetti G, Lanero S, Schiano V, Laurenzano E, Chiariello M. Leukocyte count in peripheral arterial disease: A simple, reliable, inexpensive approach to cardiovascular risk prediction. Atherosclerosis. 2010;210:288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]