Abstract

China is rich of germplasm resources of common wild rice (Oryza rufipogon Griff.) and Asian cultivated rice (O. sativa L.) which consists of two subspecies, indica and japonica. Previous studies have shown that China is one of the domestication centers of O. sativa. However, the geographic origin and the domestication times of O. sativa in China are still under debate. To settle these disputes, six chloroplast loci and four mitochondrial loci were selected to examine the relationships between 50 accessions of Asian cultivated rice and 119 accessions of common wild rice from China based on DNA sequence analysis in the present study. The results indicated that Southern China is the genetic diversity center of O. rufipogon and it might be the primary domestication region of O. sativa. Molecular dating suggested that the two subspecies had diverged 0.1 million years ago, much earlier than the beginning of rice domestication. Genetic differentiations and phylogeography analyses indicated that indica was domesticated from tropical O. rufipogon while japonica was domesticated from O. rufipogon which located in higher latitude. These results provided molecular evidences for the hypotheses of (i) Southern China is the origin center of O. sativa in China and (ii) the two subspecies of O. sativa were domesticated multiple times.

Introduction

China is one of the most significant domestication centers. More than one hundred plants were domesticated by ancient Chinese people, such as Setaria italica, Glycine max, Camellia sinensis, Oryza sativa, etc [1]. O. sativa, also known as Asian cultivated rice, is the most important crop in China today. It takes about 30% of the cultivated land and feeds over 50% population of China. Owing to its great significance, the origin and domestication of O. sativa have been studied for decades. And previous studies have proved that O. sativa was domesticated from common wild rice (O. rufipogon Griff.) about 10000 years ago in China [2], [3]. However, several crucial questions about the domestication of O. sativa are still under debate.

One fundamental question still being argued is the geographic origin of O. sativa in China. Over centuries of evolution and domestication, the germplasm resources of both O. sativa and O. rufipogon are abundant with their extremely wide distribution in China. O. sativa is cultivated in more than twenty provinces while O. rufipogon grows in seven provinces: Fujian, Hunan, Jiangxi, Yunnan, Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan, particularly with higher concentration in the last three provinces. According to the previous studies, three regions including Southern China, Yunnan-Guizhou highland and the middle and lower region of Yangtze River have been supposed to be the origin center of O. sativa based on evidences from the distribution of O. rufipogon, the rich germplasm resources of O. sativa and the discovery of rice phytoliths [4], [5], [6], [7]. However, the existing evidences supporting the mentioned hypotheses are far from being enough.

Another essential question is how many times that O. sativa has been domesticated. There are two subspecies of O. sativa, indica and japonica, which could be distinguished by a number of physiological and morphological traits such as drought tolerance, potassium chlorate resistance, phenol reaction, plant height, and leaf color, etc. There were two hypotheses about the domestication progress of the two subspecies: one has been popular for decades and is still argued in some papers recently, suggesting that indica and japonica were domesticated from one population of O. rufipogon, which was known as ‘Single Origin’ [8], [9], [10]; while the other has obtained much support from several genetic distance studies, suggesting that indica and japonica were domesticated separately from different O. rufipogon progenitors (namely ‘Multiple Origin’) [11], [12]. At present, whether indica and japonica were domesticated from a single or multiple domestication events is still being argued. A question closely related to this puzzle is when indica and japonica diverged. If indica and japonica were domesticated from the same group of O. rufipogon, the divergence might occur during the artificial selection. But if the divergence had completed before the domestication, the two subspecies must have been domesticated from two differentiated O. rufipogon groups.

In the northern hemisphere, the Tropic of Cancer (TOC, 23.5° N) represents the northernmost position where the sun is directly overhead at the June solstice, and is the recognized boundary for tropical and subtropical rice. O. rufipogon in China could be divided into two groups by the TOC, tropical O. rufipogon and subtropical O. rufipogon. One study based on the photoperiod genes had suggested that both indica and japonica had closer relationship with tropical O. rufipogon than subtropical O. rufipogon [13]. Whether the two subspecies show close affinity to tropical O. rufipogon or subtropical O. rufipogon in organelle genomes would be examined in the present study. Since O. sativa was more likely to be domesticated from the O. rufipogon group which had closer relationship with it, whether tropical O. rufipogon or subtropical O. rufipogon was the ancestor of O. sativa also could be revealed by the examination.

The DNA of organelles has been widely used in the phylogenetic analysis because of its slower nucleotide substitutions rates, uniparental inheritance and absence of intermolecular recombination [14], [15]. Ten fragments from chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes were chosen and sequenced to determine the origin and domestication process of O. sativa in China. Among the ten fragments, six loci were from chloroplast genome and four loci were from mitochondrial genome. And intergenic spaces, introns and coding regions all were included in.

In the present study, we would like to answer the following questions:

What is the diversity of the organelle genes in O. sativa and O. rufipogon?

Whether indica and japonica were domesticated from one group or multiple groups of O. rufipogon and when did they diverge?

Where was the domestication center of O. sativa in China?

Were indica and japonica domesticated from tropical O. rufipogon or subtropical O. rufipogon?

Materials and Methods

Sampling and Choice of Loci

The materials used in this study included 50 accessions of cultivated rice, one accession of O. barthii and 119 accessions of O. rufipogon (Table S1). Distributions of the samples were shown in Figure S1. The cultivated accessions are all landrace (pure-line varieties developed by farmers without artificial intercrossing), containing 27 indica and 23 japonica cultivars from 25 provinces in China. The subtropical O. rufipogon group included 46 accessions from Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hunan, Yunnan and Jiangxi provinces, while the tropical O. rufipogon group consisted of 73 accessions from Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan and Yunnan provinces. The O. rufipogon accessions had been investigated carefully in the whole life in case that the individuals with gene flow from O. sativa were not included in the samples. All O. sativa and O. rufipogon were chosen from the Chinese rice core collection with high diversity. The mini-core collections of O. sativa and O. rufipogon in China were selected from the Chinese national germplasm collections which included 50526 landraces and more than 10000 accessions of O. rufipogon. Through a hierarchical sampling strategy, mini-core collections of O. sativa and O. rufipogon retained more than 70% of the morphological variation in all germplasm collections [16]. Typical indica and japonica varieties from the mini-core collections of O. sativa and also most all individuals of mini-core collections of O. rufipogon have been selected and used in the present study. O. sativa were obtained from Chinese National Germplasm Bank and O. rufipogon was procured from Guangzhou and Nanning Wild Rice Germplasm Banks. O. barthii was provided by the International Rice Research Institute and used as outgroup. To distinguish indica and japonica, we had investigated all individuals by Cheng’s Index Method [17] which has been popularly used in China to identify indica and japonica.

Six fragments of chloroplast genome (trnG-trnfM, atp1, trnT-trnL, trnC-ycf6, nhdC-trnV, and intron of rps16) and four fragments of mitochondrial genome (cox3, cox1, rps2-trnfM, and intron of nhd4) were selected and sequenced for all samples (Table S2). Among these loci, trnG-trnfM, trnT-trnL, trnC-ycf6, nhdC-trnV and rps2-trnfM were the internal sequences; rps16 and nhd4 were introns; atp1, cox3 and cox1 were the coding regions.

DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

Chloroplast DNA and mitochondrial DNA were extracted from fresh seedling leaves [18] and nuclear DNA had been cleared out completely. All of the amplifications with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were performed in a total of 25 µl reaction mixture using a TProfessional Thermocycler (Biometra, Germany) with 10–30 ng genomic DNA. The reaction mixture included 0.2 µM of each primer, 200 µM of each dNTP, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH = 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 U HiFi DNA polymerase (Transgen, China). The amplification conditions were 94°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C (30 s), 55°C (30 s), and 72°C (1.5 min), and a final extension at 72°C (10 min). The PCR products were electrophoresed in 1.2% agarose gels, and the DNA fragments were cut from the gel and purified using the Tiangen Gel Extraction kit (Tiangen, China). Sequencing reactions were performed by an ABI 3730 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, United States). Because Taq errors did occur, when polymorphisms were only found in one of the accessions, this accession was re-sequenced with the cloning step to ensure those results were not false polymorphisms.

Statistical Analysis

The DNA sequences were aligned using the ClustalX 1.83 program [19] and manually adjusted in BioEdit [20]. Insertions/deletions (indels) were not included in the analysis. We calculated the number of segregating sites (S), the number of haplotypes (h), haplotype diversity (Hd) and two parameters of nucleotide diversity, (π) [21] and Watterson’s estimator from S (θw) [22], using DNAsp version 5.0 [23]. Pairwise FST, generally expressed as the proportion of genetic diversity due to allele frequency differences among populations, was used to measure differentiation between groups, as implemented in Arlequin 3.01 [24].

Haplotype network was constructed by mutational steps with NETWORK 4.5 [25]. Those networks represent the genetic distance of DNA sequences or alleles and were mainly composed of circles of different sizes and colors and lines that linked those circles. The circle size is proportional to the number of samples within a given haplotype, and the lines between the haplotypes represent mutational steps between the alleles. The numbers next to the circle represent the haplotype number. Each color of the circles represents a species or subspecies. If more than one nucleotide difference existed between the linked haplotypes, it is indicated by a number next to the lines.

The phylogenetic relationships among the haplotypes of the three nuclear loci and one combined chloroplast and mitochondrial gene region were constructed by Neighbor-joining (NJ) [26] analysis using PAUP* version 4.0b10 [27]. Gaps were treated as missing values, and these sites were excluded from the data matrix. In the NJ analysis, we chose to follow Kimura’s 2-parameter (K2P) model [28] and the nonparametric bootstrap test was performed to quantify the confidence level of internal nodes with 1000 replications.

Structure analysis was used to assign individual clusters to groups for all genes. A Bayesian approach assigned individuals to a specific number of clusters (K) based on inferred allele frequencies in populations [29]. The optimal number of genetic clusters was identified using log likelihood, based on independent runs at K = 2–10. All runs were iterated for 100 000 Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling steps following 100 000 burn in steps and a thinning interval of 10 steps. Each individual consisted of a mixture of different genomic components referred to by different colors. If the color of one cluster was more than 60% in one individual, we supposed it belonged to this cluster.

Because the substitution rates of the plant mitochondrial, chloroplast, and nuclear DNA had been reported to approximate at 1∶3∶12 [30] and the evolutionary rate of rice nuclear genes had been estimated to be 7.16 × 10−9 [31], we estimated the divergence time between indica and japonica by a molecular clock, using the formula T = 3N/Lµ for chloroplast genes and T = 12N/Lµ for mitochondrial genes, where µ corresponds to the absolute rate of substitutions per site per year of nuclear genes, N is the estimated numbers of substituted sites between indica and japonica, and L is the total length of all loci.

Results

Nucleotide Diversity

We sequenced ten unlinked organelle loci included rps133, trnG-trnfM, atp1, trnT-trnL, trnC-ycf6, nhdC-trnV, cox3, cox1, nhd4 and rps2-trnfM for 50 accessions of O. sativa and 119 accessions of O. rufipogon. The total length of the ten loci was 9089–9233. The number of insertion-deletion (indel) events ranged from 7 to12.

Standard statistics of sequence polymorphisms for all loci are shown in Table 1. For O. sativa, 11 and 3 polymorphisms were found in chloroplast and mitochondrial, respectively. For O. rufipogon, more polymorphisms were identified, including 15 and 8 polymorphisms in chloroplast and mitochondrial, respectively. θw, which represents the diversity of the nucleotide polymorphisms of O. sativa, was 0.45 and 0.18 in chloroplast and mitochondrial, respectively. θw of O. rufipogon also was higher than that of O. sativa, being 0.52 and 0.41 in chloroplast and mitochondrial, respectively. More polymorphisms and higher diversity of polymorphisms indicated that genetic diversity of the O. rufipogon was higher than that of O. sativa in chloroplast and mitochondrial genes. As expected, the values of S, h, Hd, π and θw of chloroplast loci all were higher than mitochondrial loci. This result was in line with the fact that the mitochondrial DNA is more conservative and the evolution rate of chloroplast DNA is higher than mitochondrial DNA in rice.

Table 1. Summary of nucleotide polymorphisms.

| Organelle | Species | S | h | Hd | π×103 | θw×103 |

| Chloroplast | O. sativa | 11 | 3 | 0.548 | 0.95 | 0.45 |

| O. rufipogon | 15 | 10 | 0.771 | 1.13 | 0.52 | |

| Mitochondrial | O. sativa | 3 | 2 | 0.507 | 0.42 | 0.18 |

| O. rufipogon | 8 | 7 | 0.554 | 0.44 | 0.41 | |

| Combined | O. sativa | 14 | 3 | 0.548 | 0.74 | 0.34 |

| O. rufipogon | 23 | 15 | 0.793 | 0.85 | 0.47 |

S: number of segregating sites; h: number of haplotypes; Hd: haplotype diversity; π: nucleotide diversity; θw: Watterson’s parameter for silent sites.

Haplotype Variation

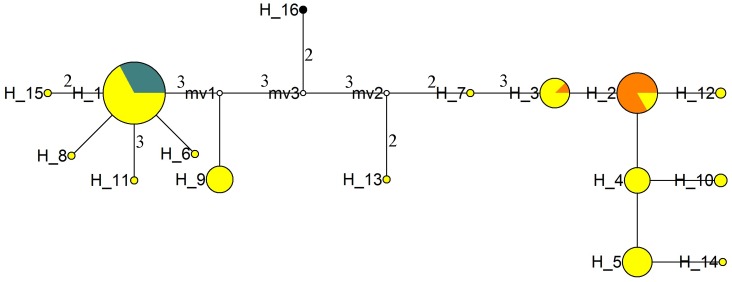

One haplotype of O. barthii, three haplotypes of O. sativa and fifteen haplotypes of O. rufipogon were found for all loci. Figure 1 shows the network constructed by all haplotypes. All O. sativa were included in H1, H2 and H3, and a great many of O. rufipogon also existed in these haplotypes and shared the haplotypes with O. sativa. Since O. sativa was most likely domesticated from the O. rufipogon individuals with the same nucleotide variations, it could be concluded that the wild accessions in H1, H2 and H3 were the ancestors of the cultivated accessions. Furthermore, in this haplotype network, japonica accessions were only included in H1 and indica accessions were contained in H2 and H3. Thus, we concluded that japonica was domesticated from the O. rufipogon in H1 and indica was domesticated from the O. rufipogon in H2 and H3.

Figure 1. Haplotype network constructed by all loci for O.

sativa and O. rufipogon . The circle size is proportional to the quantity of samples within a given haplotype, and the numbers next to the circle represent the haplotype number. Lines between haplotypes represent mutational steps between alleles. When more than one nucleotide difference existed between linked haplotypes, this is indicated by the numbers next to the lines. Colors for species: yellow, O. rufipogon; orange, O. sativa indica; blue, O. sativa japonica; and black, O. barthii.

In the network, H16, which represented the outgroup from O. barthii, was in the middle and divided the other haplotypes into two groups. One group included H1, H6, H8, H9, H11, H15 and the other group contained H2, H3, H4, H5, H7, H10, H12, H13 and H14. This result suggested that O. rufipogon might have already diverged into two groups. As analyzed above, H1 and H2, H3 were the direct progenitors of japonica and indica respectively. These two groups could be named as indica-like and japonica-like groups.

Phylogenetic Analysis

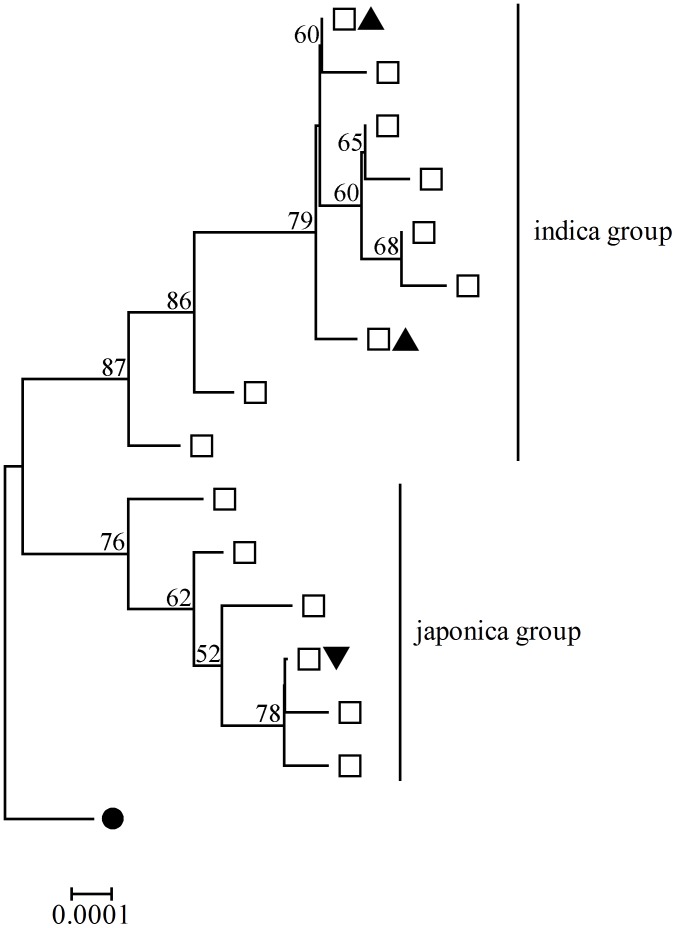

The phylogenies tree of the combined chloroplast and mitochondrial loci were constructed by NJ method (Figure 2). Because of the overall similarity between O. sativa and O. rufipogon, the phylogenetic tree should not be treated as true genealogies but rather an approximation of genealogy [32]. As shown in Figure 2, all branches were clearly divided into two groups, and the branches shared by indica and japonica with O. rufipogon were in the upper and lower groups respectively. The phylogenetic analysis strongly supported that japonica and indica were domesticated from japonica-like O. rufipogon and indica-like O. rufipogon independently.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree of combined chloroplastic and mitochondrial loci.

Bootstrap values above 50% are shown on the trees. The accessions contained in the branches were indicated by different symbols: O. rufipogon alleles by open squares, indica alleles by filled triangles and japonica by inverted filled triangles. The tree was rooted with O. barthii allele which is indicated by solid circles.

Structure Analysis

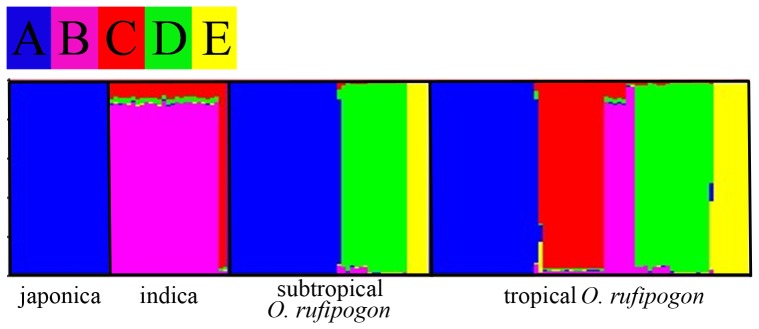

Structure analysis for all O. sativa and O. rufipogon was performed from K = 2 to K = 10. When K = 5, the value of Ln P (D) was the largest (Figure S2) and the result was stable. Five clusters were identified for all samples (Figure 3), among which three were shared by both O. sativa and O. rufipogon. Indica and japonica was clearly separated, and japonica fell into cluster A and indica was divided into cluster B and C. Cluster A, B and C were also included in O. rufipogon. O. rufipogon in the same clusters of indica and japonica might be the progenitors of indica and japonica respectively. This result also supports the conclusion that japonica and indica were domesticated from different O. rufipogon groups.

Figure 3. Population structuring of O.

sativa and O. rufipogon . STRUCTURE was constructed by all loci. K = 5. Clusters are indicated by different colors. Samples included in all clusters are listed in Table S1.

What’s more, cluster B and C were only detected in tropical O. rufipogon, revealing indica was domesticated from tropical O. rufipogon rather than subtropical O. rufipogon. While cluster A were contained both in tropical O. rufipogon and subtropical O. rufipogon, indicating a more wide geographic origin of japonica.

Molecular Dating of the Divergence of Indica and Japonica

In total, twenty three SNPs had been detected in chloroplast and mitochondrial loci for all O. sativa and O. rufipogon. Among these SNPs, some could be used to distinguish indica and japonica varieties and divide the O. rufipogon into indica-like and japonica like groups. Ten and three SNPs of this kind had been found in chloroplast loci and mitochondrial loci respectively. Using the formulas T = 3N/Lµ for chloroplast loci and T = 12N/Lµ for mitochondrial loci, we estimated the divergence time for indica and japonica were 0.08 million years ago (mya) in chloroplast genome and 0.13 mya in mitochondrial genome. Thus, we concluded that the divergence of indica and japonica were completed at about 0.1 mya.

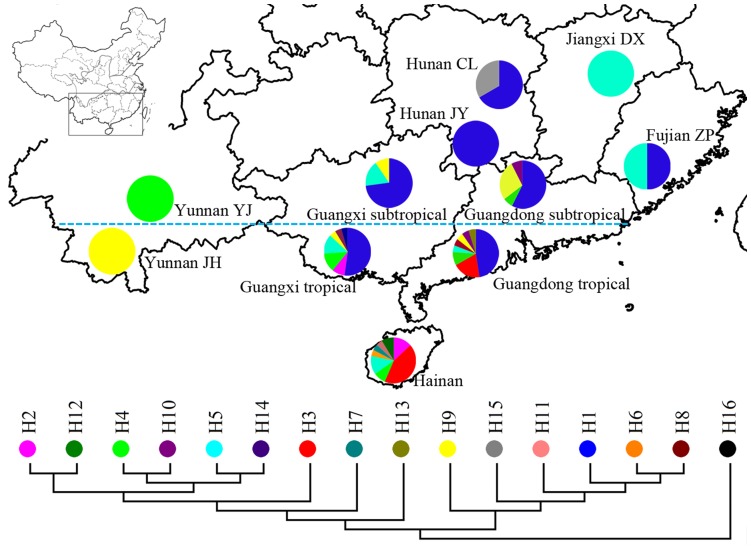

Distribution of the Ancestors of O. sativa

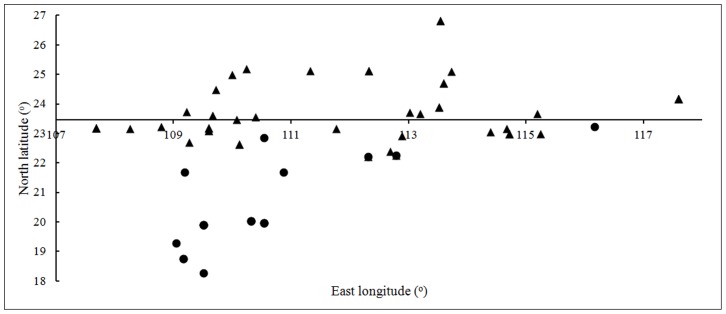

The distribution of fifteen haplotypes of O. rufipogon was shown in Figure 4. And we found that the haplotypes were closely related to particular geographic locations. H1 existed in Guangdong, Guangxi, Fujian and Hunan; H2 existed in Guangxi tropical and Hainan; H3 were included in Guangdong tropical and Hainan. Because O. rufipogon contained in H1 might be the ancestors of japonica are O. rufipogon included in H2 and H3 might be the ancestors of indica, we supposed ancestors of japonica mainly grew in Guangdong, Guangxi, Fujian and Hunan while ancestors of indica mainly existed in Guangdong tropical, Guangxi tropical and Hainan. To find out the exact origin of indica and japonica, a coordinate diagram had been constructed by the longitude and latitude of the O. rufipogon accessions in H1, H2 and H3 (Figure 5). Locations of the individuals in H1 ranged from 22°15′ (N) to 26°48′ (N) while locations of the accessions in H2 and H3 ranged from 18°15′ (N) to 23°18′ (N). The latitude of the distribution of ancestors of indica was lower than that of japonica, indicating that indica and japonica might be domesticated from different regions in Southern China. This map also showed that ancestors of indica located in south of the TOC and ancestors of japonica mainly located in north of the TOC and there were only a few accessions located in the south nearby the TOC. This result indicated indica might be domesticated from tropical O. rufipogon and japonica was domesticated from O. rufipogon which located in higher latitude region.

Figure 4. A map showing the sampled populations of O.

rufipogon and the distribution of haplotypes. Detailed information of the samples is provided in Table S1. Phylogenetic relationship of the haplotype based on the NJ analysis is indicated below the map. Pie charts show the proportions of the haplotypes within each population. Haplotypes are indicated by different colors. The Tropical of Cancer is indicated by the green dotted line. Codes: CL, Chaling; DX, Dongxiang; JH, Jinghong; JY, Jiangyong; YJ, Yuanjiang; ZP, Zhangpu;

Figure 5. Longitude and latitude of the O.

rufipogon from H1, H2 and H3. Accessions from H2 and H3 are indicated by circles and accessions from H1 are indicated by triangles. The horizontal ordinate origins from 23.5° (N) which is the Tropical of Cancer located in.

Genetic Differentiation between O. sativa and O. rufipogon

Pairwise FST values were calculated to measure genetic differentiation between different O. sativa and O. rufipogon groups. The genetic differentiation between japonica and subtropical O. rufipogon was smaller than that between japonica and tropical O. rufipogon. In contrast, the genetic differentiation between indica and subtropical O. rufipogon was larger than that between indica and tropical O. rufipogon (Table 2). Assuming the different FST values are an indicator of genetic affinity, we proposed that indica had a closer relationship with tropical O. rufipogon while japonica had a closer relationship with subtropical O. rufipogon.

Table 2. Summary statistic of pairwise divergence (FST) between groups.

| Groups | Tropical O. rufipogon | Subtropical O. rufipogon | Tropical ancestors | Subtropical ancestors |

| japonica | 0.5655 | 0.3526 | 0.4314 | 0 |

| indica | 0.2775 | 0.5089 | 0.4507 | 0.9962 |

Discussion

Genetic Diversity of O. sativa and O. rufipogon in China

The genetic diversity of nuclear genes in O. sativa and O. rufipogon has been investigated based on molecular markers, SNPs and indels [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]. These researches had suggested that there was a bottleneck in the domestication of O. sativa, and O. rufipogon from Southern China has the highest diversity. We also got the similar result in organelle DNA of O. sativa and O. rufipogon in China.

Although O. sativa accessions used in the present research were collected from the Chinese rice core collection and all are landrace, only three haplotypes were detected in all loci. Using the haplotype numbers as a proxy for diversity, O. rufipogon contained 100% of the total haplotype diversity, whereas O. sativa only contained about 20% of the total haplotype diversity of chloroplast and mitochondrial genome. The comparison of the levels of diversity between O. sativa and O. rufipogon indicated that O. sativa reduced an 80% subset of the total genetic variation of O. rufipogon in organelle genomes. The genetic diversity maintained in cultivated rice was much less than the wild progenitors, indicating a severe genetic bottleneck during domestication.

In the present study, haplotype numbers of O. rufipogon from each province were calculated (Figure S3). The haplotype numbers of O. rufipogon for all loci from Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Hunan, Jiangxi and Yunnan was 2, 8, 7, 8, 2, 1 and 2, respectively. This result indicated that O. rufipogon from Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan (together being named as Southern China) had the highest organelle DNA diversity. The haplotype numbers of organelle DNA of O. rufipogon from Southern China was 14, taking up to 93% of the total haplotype numbers and about three times of that from all other provinces. Although this phenomenon might be caused by different numbers of sampled populations and the fact that common wild rice populations in the wild in other provinces are less than in Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan, our results support the opinion that O. rufipogon from Southern China contained the most diversity of organelle DNA and Southern China might be the genetic diversity center of O. rufipogon in China.

There were 14 haplotypes of tropical O. rufipogon for all loci, containing most diversity of all O. rufipogon, while haplotype number of subtropical O. rufipogon was 6, only representing 40% of the total diversity. The genetic diversity of tropical O. rufipogon was much higher than subtropical O. rufipogon. This result may provide an explanation to the fact that the diversity of indica was higher than japonica because indica was domesticated from tropical O. rufipogon which contained higher genetic diversity.

Domestication Model of O. sativa in China

Although the point that indica and japonica were domesticated independently has obtained much support [38], [39], [40], some papers published even recently still insisted that O. sativa was only domesticated once from group of O. rufipogon [8], [9], [10], [41], [42]. The opinions that whether indica and japonica were domesticated single or multiple times are considerably controversial [43], [44], [45], [46]. Our results strongly support the multiple origin model rather than the single one. In the present study, the phylogenetic analysis indicated that O. rufipogon diverged into two groups, indica-like and japonica-like, and plenty of individuals with the same polymorphisms of indica and japonica existed in indica-like and japonica-like O. rufipogon. It could be concluded that indica and japonica were domesticated separately because they had evolved from different ancestors. Since all O. rufipogon samples were selected from Chinese rice core collection which can highly represent the diversity of common wild rice in China and we had carefully monitored the whole life of the wild samples to ensure that the individuals with gene flow from O. sativa were not included in, we confirmed that those O. rufipogon accessions with the same polymorphisms of O. sativa did not inherit the organelle genomes from cultivated parent and were the direct progenitors of indica and japonica.

Recently, it's reported that the gene flow of domestication genes in nuclear genome from japonica to indica occurred during the domestication of O. sativa [39], [40]. However, this phenomenon was not detected in organelle DNA in this study. These results different from the previous researches in nuclear genome may have been caused by the uniparental inheritance of organelle genomes. Because the organelle genomes of the next generation are only inherited from the female parent, the introgression between indica and japonica rarely occurred.

It is believed that O. sativa was domesticated about 10000 years ago in East Asia [3]. The molecular dating in the present study revealed that indica and japonica diverged in about 0.1 mya, which indicated that the divergence time of indica and japonica was much earlier than the beginning of rice domestication. This result proved that indica and japonica had already separated in O. rufipogon before domestication. Divergence time of indica and japonica also has been calculated in previous researches [36], [47]. By analyzing the divergence of indica and japonica in nuclear genes, the two subspecies was supposed to separate approximately 0.4 mya. And based on the total number of nucleotide substitutions between the chloroplast genomes of 93-11 and PA64S, the divergence of indica and japonica was dated as 0.86 to 2 mya. Both studies of nuclear and chloroplast genes have revealed that the divergence of indica and japonica occurred much earlier than the beginning of rice domestication.

The genetic differentiation between tropical O. rufipogon and indica was significantly smaller than that between subtropical O. rufipogon and indica, suggesting indica has a closer relationship with tropical O. rufipogon. Furthermore, latitudes of the ancestors of indica in China shown in Figure 5 were all in the south of the TOC, from which we concluded that indica was domesticated from tropical O. rufipogon. Although the genetic differentiation analysis indicated japonica was closer to subtropical O. rufipogon than to tropical O. rufipogon, the distribution of the ancestors of japonica was not only in subtropical area but also in tropical region nearby the TOC. Thus japonica may have been domesticated from subtropical O. rufipogon or tropical O. rufipogon nearby the TOC.

Indica and japonica grow in different areas in China and adapt to different environments. Generally, indica grows in the lower latitude regions and adapts to a higher temperature and shorter light period, while japonica grows in higher latitude regions and adapts to a lower temperature and longer light period. The similar phenomenon was detected in the ancestors of indica and japonica. The latitude of the distribution of ancestors of indica was lower than that of the ancestors of japonica, suggesting ancestors of indica grew in the conditions of warmer climate and shorter light period. We supposed that the adaptability of warmer climate and shorter light period of the indica-like O. rufipogon had been inherited by indica, leading to the lower location of indica compared with japonica.

Domestication of rice in China also has been analyzed by nuclear genes such as ITS, SS, Hd1, Ehd1 and Waxy by our group [42]. The results inferred by nuclear genes and organelle genes were not all the same. For neutral nuclear genes, such as ITS and SS, the revealed domestication process was quite similar to organelle genes. Indica and japona might have been domesticated from indica-like and japonica-like O. rufipogon groups. But for the domesticated gene such as Hd1 and Waxy, the results were different. Functional Hd1 gene in O. sativa evolved like orangelle genes, but nonfunctional Hd1 gene might evolve from nonfunctional Hd1 gene in O. rufipogon. For Waxy, it was first domesticated in japonica and then transferred into indica later. The domestication of nuclear genes is much more complex than that of organelle genes.

Domestication Center of O. sativa in China

Six major haplotypes of O. rufipogon of organelle DNA were detected: H1, H2, H3, H4, H5 and H9. As shown in Figure 4, each haplotype was located in a limited area, and Guangdong and Guangxi were the center of the distribution region: H1 was included in the east and north direction of the center (Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi and Hunan); H2 was included in south direction of the center (Guangxi and Hainan); H3 was also included in south direction of the center (Guangdong and Hainan); H4 was included in south and west direction of the center (Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan and Yunnan); H5 was included in south and east direction of the center (Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Fujian and Jiangxi); H9 was included in west direction of the center (Guangdong, Guangxi and Yunnan), suggesting Guangdong and Guangxi might be the genetic center of O. rufipogon in China and O. rufipogon in other areas may be derived from those of Guangdong and Guangxi.

The debate of the geographic origin of O. sativa in China is mainly focused on three regions with different evidences: Southern China, Yunnan-Guizhou Highland and the middle and lower region of Yangtze River. Southern China has been supposed to be the origin center of O. sativa because the ancestors of cultivated rice (O. rufipogon) only located in the eight provinces of South China [4]. Whereas, due to the highest genetic diversity of cultivated rice in Yunnan and Guizhou provinces, a hypothesis popular in the 1970s identified Yunnan-Guizhou highland as the origin site of O. sativa in Asia [5]. From 1970s, many rice phytoliths with long history were found in different archaeological sites in the middle and lower region of Yangtze River, some scientists deduced that this region was the geographic origin of rice domestication and cultivation in China [6], [7]. Since Guangdong and Guangxi belong to Southern China, Yunnan belongs to Yunnan-Guizhou Highland, Dongxiang county in Jiangxi belongs to the middle and lower region of Yangtze River, and O. rufipogon existed in all these regions, examining the relationship between O. sativa and O. rufipogon from these regions would provide molecular evidence to verify these hypotheses.

By analyzing SNPs of O. rufipogon accessions in different haplotypes, we found that O. rufipogon accessions in H1 had the same nucleotide polymorphisms with japonica and O. rufipogon accessions in H2 and H3 had the same nucleotide polymorphisms with indica, indicating O. rufipogon accessions in H1 and H2, H3 may be the ancestors of japonica and indica respectively. As we mentioned above, O. rufipogon individuals in H1 were from Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi and Hunan while O. rufipogon individuals in H2 and H3 were from Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan. This result clearly showed that O. rufipogon from Yunnan and Jiangxi were not the progenitors of O. sativa and O. sativa was domesticated from Southern China rather than from Yunnan-Guizhou Highland and the middle and lower region of Yangtze River.

Although the samples in Yunnan and Jiangxi are limited, they could highly represent the diversity in these areas. Thus, because O. rufipogon from Yunnan and Jiangxi are not in H1, H2 and H3, it could be concluded that O. sativa was not domesticated from these areas. In the history, the distribution of O. rufipogon might different from today, and O. rufipogon might be more than today in Yunnan and Jiangxi. The results in this study were concluded from the distribution of O. rufipogon currently in China. But we believed our analysis had explained the results quite well and these results could be helpful for understanding the domestication process of O. sativa in China. Previous phylogeographic study has suggested indica was domesticated in Southeast and South Asia whereas japonica originated from Southern China [12]. Another research published recently argued only indica was domesticated from China [10]. However, in the present study, both ancestors of indica and japonica were detected in Southern China. We supposed that not only japonica but also indica was domesticated in Southern China. To confirm whether indica was domesticated from Southeast and South Asia or only from Southern China, plenty representative O. rufipogon individuals from Southeast and South Asia and Southern China should be together included in the samples for further research. The question whether indica was domesticated from China or South Asia remains open.

Although the wild samples might have gene flow from cultivated rice, the results showed that plenty of wild samples had the same polymorphisms with indica and japonica respectively. These wild samples were in a wide range. It is not possible all these wild samples had gene flow from O. sativa. The introgression between O. sativa to O. rufipogon had been detected in our previous study [42] and the result indicated the introgression was at a low level. What’s more, the O. rufipogon accessions had been investigated carefully in the whole life to prevent that the individuals which had gene flow from O. sativa were not included in the samples. Therefore we thought the introgression from O. sativa to O. rufipogon is at a low level and human activities could rarely impact the conclusions of the study.

A recently published paper suggests O. rufipogon had two subpopulations: ruf I and ruf II and indica was domesticated from ruf I in China [10]. In the present study, the result clearly showed both japonca and indica were domesticated from O. rufipogon. The different conclusion in the mentioned paper might be caused by the limited samples from China. Only 22 accessions of O. rufipogon accessions from China had been used and the detailed information about these accessions was not provided in the paper. We supposed the O. rufipogon accessions which might be the ancestor of japonica were not included in the samples.

According to the rice diversity researches, O. sativa could be divided into five subspecies by SSR and SNPs: indica, aus, aromatic or Group V, temperate japonica and tropical japonica [48], [49]. Generally, it is believed that varieties of aromatic, tropical japonica and aus are rarely cultivated in China. Samples of these groups from South and Southeast Asia had been obtained and compared with the cultivated accessions used in the present study. Structure analysis obviously showed that japonica and indica materials used in our research could be divided into temperate japonica and indica population, respectively (Figure S4). Therefore, all conclusions above about japonica should be applicable to temperate japonica. To clearly detect the domestication of the five groups of O. sativa, varieties of all five groups and O. rufipogon coming from Southeast and South Asia should be added to the samples.

O. nivara has been regarded as another ancestor of O. sativa by genome sequences analysis of 50 accessions of cultivated and wild rice [50]. The two wild progenitors of cultivated rice had genetic divergence and ecological distinction [41]. O. rufipogon is perennial, photoperiod sensitive and largely cross-fertilized; whereas O. nivara is annual, photoperiod insensitive and predominantly self-fertilized. O. rufipogon existed from South China to North Australia, while O. nivara is mainly found in South and Southeast Asia and have not found in China. Thus, O. nivara was not included in the present study. To reveal the dynamic process of rice domestication clearly, O. nivara should be included in the samples in future studies.

Supporting Information

Geographic origins of the materials in China. Red circles indicate indica; blue circles indicate japonica; green triangles indicate O. rufipogon.

(TIF)

K value of the Structure analysis (K = 2–10).

(TIF)

Haplotype numbers of O . rufipogon from different provinces.

(TIF)

Structure of cultivated accessions and varieties of aromatic, tropical japonica and aus. K = 5. Detailed information about the varieties of aromatic, tropical japonica and aus are shown in Table S3.

(TIF)

Collection details of accessions of O. sativa and O. rufipogon from China.

(DOC)

Summary of the genes sequenced and the primer sequences used in this study.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank the Chinese National Germplasm Bank for providing the seeds of O. sativa, Guangzhou and Nanning Wild Rice Germplasm Banks for providing the leaves of wild rice, and International Rice Research Institute for providing seeds of O. barthii.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the program of Conservation and Sustainable Utilization of Wild Relatives of Crops by China Ministry of Agriculture (201003021). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Smith BD (2006) Eastern North America as an independent center of plant domestication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 12223–12228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jiang L, Liu L (2006) New evidence for the origins of sedentism and rice domestication in the Lower Yangzi River, China. Antiquity 80: 355–361. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vaughan DA, Morishima H, Kadowaki K (2003) Diversity in the Oryza genus. Curr Opin Plant Biol 6: 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ting Y (1957) The origin and evolution of cultivated rice in China. Acta Agr Sinica 8: 243–260. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu Z (1975) The origin and development of cultivated rice in China. Acta Genet Sinica 2: 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zong Y, Chen Z, Innes JB, Chen C, Wang Z, et al. (2007) Fire and flood management of coastal swamp enabled first rice paddy cultivation in east China. Nature 449: 459–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fuller DQ, Qin L, Zheng Y, Zhao Z, Chen X, et al. (2009) The domestication process and domestication rate in rice: spikelet bases from the Lower Yangtze. Science 323: 1607–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gao LZ, Innan H (2008) Nonindependent domestication of the two rice subspecies, Oryza sativa ssp. Indica and ssp. japonica, demonstrated by multilocus microsatellites. Genetics 179: 965–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Molina J, Sikora M, Garud N, Flowers JM, Rubinstein S, et al. (2011) Molecular evidence for a single evolutionary origin of domesticated rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 8351–8356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huang P, Molina J, Flowers JM, Rubinstein S, Jackson SA, et al. (2012) Phylogeography of Asian wild rice, Oryza rufipogon: a genome-wide view. Mol Ecol 21: 4593–4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cheng C, Motohashi R, Tsuchimoto S, Fukuta Y, Ohtsubo H, et al. (2003) Polyphyletic origin of cultivated rice: based on the interspersion pattern of SINEs. Mol Biol Evol 20: 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Londo JP, Chiang YC, Hung KH, Chiang TY, Schaal BA (2006) Phylogeography of Asian wild rice, Oryza rufipogon, reveals multiple independent domestications of cultivated rice, O. sativa . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 9578–9583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang CL, Hung CY, Chiang YC, Hwang CC, Hsu TW, et al. (2012) Footprints of Natural and artificial selection for photoperiod pathway genes in Oryza . Plant J 70: 769–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kumagai M, Wang L, Ueda S (2010) Genetic diversity and evolutionary relationships in genus Oryza revealed by using highly variable regions of chloroplast DNA. Gene 462: 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dong WP, Liu J, Yu J, Wang L, Zhou SL (2012) Highly variable chloroplast markers for evaluating plant phylogeny at low taxonomic levels and for DNA barcoding. PLoS One 7: e35071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang HL, Zhang DL, Wang MX, Sun JL, Qi YW, et al. (2011) A core collection and mini core collection of Oryza sativa L. in China. Theor Appl Genet 122: 49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lu BR, Cai XX, Jin X (2009) Efficient indica and japonica rice identification based on the InDel molecular method: Its implication in rice breeding and evolutionary research. Prog Nat Sci 19: 1241–1252. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Triboush SO, Danilenko NG, Davydenko OG (1998) A method for isolation of chloroplast DNA and mitochondrial DNA from sunflower. Plant Mol Biol Rep 16: 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thompson JD, Gibson Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG (1997) The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 24: 4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hall TA (1999) Bioedit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series 41: 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nei M (1987) Molecular evolutionary genetics. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Watterson GA (1975) On the number of segregating sites in genetical models without recombination. Theor Popul Biol 7: 256–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rozas J (2009) DNA sequence polymorphism analysis using DnaSP. Methods Mol Biol 537: 337–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Excoffier L, Smouse PE, Quattro JM (1992) Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics 131: 471–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Rohl A (1999) Median-joining networks for interring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 16: 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4: 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swofford DL (2002) PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (and Other Methods), Version 4.0. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kimura M (1980) A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of DNA sequences. J Mol Evol 16: 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK (2003) Inference of population structure: extensions to linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 164: 1567–1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wolfe KH, Li WH, Sharp PM (1987) Rates of nucleotide substitution vary greatly among plant mitochondrial, chloroplast, and nuclear DNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84: 9054–9058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gaut BS, Morton BR, McCaig BC, Clegg MT (1996) Substitution rate comparisons between grasses and palms: synonymous rate differences at the nuclear gene Adh parallel rate differences at the plastid gene rbcL . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 10274–10279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zheng XM, Ge S (2010) Ecological divergence in the presence of gene flow in two closely related Oryza species (O. rufipogon and O. nivara). Mol Ecol 19: 2439–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun CQ, Wang XK, Li ZC, Yoshimura A, Iwata N (2001) Comparison of the genetic diversity of common wild rice (Oryza rufipogon Griff.) and cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.) using RFLP markers. Theor Appl Genet 102: 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gao LZ (2004) Population structure and conservation genetics of wild rice Oryza rufipogon (Poaceae): a region-wide perspective from microsatellite variation. Mol Ecol 13: 1009–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang MX, Zhang HL, Zhang DL, Qi YW, Fan ZL, et al. (2008) Genetic structure of Oryza rufipogon Griff. in China. Heredity 101: 527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhu QH, Ge S (2005) Phylogenetic relationships among A-genome species of the genus Oryza revealed by intron sequences of four nuclear genes. New Phytol 167: 249–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhu Q, Zheng X, Luo J, Gaut BS, Ge S (2007) Multilocus analysis of nucleotide variation of Oryza sativa and its wild relatives: severe bottleneck during domestication of rice. Mol Biol Evol 24: 875–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rakshit S, Rakshit A, Matsumura H, Takahashi Y, Hasegawa Y, et al. (2007) Large-scale DNA polymorphism study of Oryza sativa and O. rufipogon reveals the origin and divergence of Asian rice. Theor Appl Genet 114: 731–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. He Z, Zhai W, Wen H, Tang T, Wang Y, et al. (2011) Two evolutionary histories in the genome of rice: the roles of domestication genes. PLoS Genet 7: e1002100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yang C, Kawahara Y, Mizuno H, Wu J, Matsumoto T, et al. (2011) Independent domestication of Asian rice followed by gene flow from japonica to indica. Mol Bio Evol 29: 1471–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vaughan DA, Lu BR, Tomooka N (2008) The evolving story of rice evolution. Plant Sci 174: 394–408. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wei X, Qiao WH, Chen YT, Wang RS, Cao LR, et al. (2012) Domestication and geographic origin of Oryza sativa in China: insights from multilocus analysis of nucleotide variation of O. sativa and O. rufipogon . Mol Ecol 21: 5073–5087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sweeney M, McCouch S (2007) The complex history of the domestication of rice. Ann Bot 100: 951–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kovach MJ, Sweeney MT, McCouch SR (2007) New insights into the history of rice domestication. Trends Genet 23: 578–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sang T, Ge S (2007a) Genetics and phylogenetics of rice domestication. Curr Opin Genet and Dev 17: 533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sang T, Ge S (2007b) The puzzle of rice domestication. J Integr Plant Biol 49: 760–768. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tang J, Xia H, Cao M, Zhang X, Zeng W, et al. (2004) A comparison of rice chloroplast genomes. Plant physiol 135: 412–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Garris AJ, Tai TH, Coburn J, Kresovich S, McCouch S (2005) Genetic structure and diversity in Oryza sativa L. Genetics. 169: 1631–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhao K, Wright M, Kimball J, Eizenga G, McClung A, et al. (2010) Genomic diversity and introgression in O. sativa reveal the impact of domestication and breeding on the rice genome. PLoS One 5: e10780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xu X, Liu X, Ge S, Jensen DJ, Hu F, et al. (2012) Resequencing 50 accessions of cultivated and wild rice yields markers for identifying agronormically important genes. Nat Biotechnol 30: 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Geographic origins of the materials in China. Red circles indicate indica; blue circles indicate japonica; green triangles indicate O. rufipogon.

(TIF)

K value of the Structure analysis (K = 2–10).

(TIF)

Haplotype numbers of O . rufipogon from different provinces.

(TIF)

Structure of cultivated accessions and varieties of aromatic, tropical japonica and aus. K = 5. Detailed information about the varieties of aromatic, tropical japonica and aus are shown in Table S3.

(TIF)

Collection details of accessions of O. sativa and O. rufipogon from China.

(DOC)

Summary of the genes sequenced and the primer sequences used in this study.

(DOC)