Abstract

Previously, we showed that the cytochrome P450 1B1 inhibitor, 2,3´,4,5´-tetramethoxystilbene, reversed DOCA-salt induced hypertension and minimized endothelial and renal dysfunction in the rat. This study was conducted to test the hypothesis that cytochrome P450 1B1 contributes to cardiac dysfunction, and renal damage and inflammation associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension, via increased production of reactive oxygen species, and modulation of neurohumoral factors and signaling molecules. DOCA-salt increased systolic blood pressure, cardiac and renal cytochrome P450 1B1 activity, and plasma levels of catecholamines, vasopressin, and endothelin-1 in wild type (Cyp1b1+/+) mice that were minimized in Cyp1b1−/− mice. Cardiac function, assessed by echocardiography, showed that DOCA-salt increased the thickness of the left ventricular posterior and anterior walls during diastole, the left ventricular internal diameter, and end-diastolic and end-systolic volume in Cyp1b1+/+ but not Cyp1b1−/− mice; stroke volume was not altered in either genotype. DOCA-salt increased renal vascular resistance and caused vascular hypertrophy, renal fibrosis, increased renal infiltration of macrophages and T-lymphocytes, caused proteinuria, increased cardiac and renal NADPH oxidase activity, production of reactive oxygen species, and activities of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK and c-Src; these were all reduced in DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1−/− mice. Renal and cardiac levels of eicosanoids were not altered in either genotype of mice. These data suggest that in DOCA-salt hypertension in mice, cytochrome P450 1B1 plays a pivotal role in cardiovascular dysfunction, renal damage and inflammation, and increased levels of catecholamines, vasopressin, and endothelin-1, consequent to generation of reactive oxygen species and activation of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and c-Src independent of eicosanoids.

Keywords: DOCA-salt, cytochrome P450 1B1, hypertension, oxidative stress, cardiac dysfunction, renal fibrosis, inflammation

Introduction

Deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) with 1% salt in drinking water (DOCA-salt) results in salt and water retention, plasma volume expansion, and hypertension that is associated with low levels of angiotensin II (Ang II) (1). However, levels of arginine vasopressin (AVP), catecholamines, and endothelin-1 (ET-1) are increased in this model and contribute to hypertension (2–4). These agents also activate phospholipase A2 and release arachidonic acid (AA) from tissue phospholipids (5–7). Metabolites of AA generated via lipoxygenase (LO) or cytochrome P450 (CYP) 4A ω-hydroxylase have been implicated in spontaneous hypertensive rats, as well as Ang II and DOCA-salt models of hypertension (8–12). Metabolism of AA also results in generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause endothelial dysfunction and contribute to the development of various models of hypertension including DOCA-salt-induced hypertension (13–17).

Recently, we reported that CYP1B1, which can also metabolize AA in vitro into hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) (18), contributes to Ang II-induced vascular smooth muscle cell growth (19), hypertension and associated pathophysiological changes, renal dysfunction and end organ damage (20–22). Moreover, we showed that in rats, 2,3´,4,5´-tetramethoxystilbene (TMS), a selective inhibitor of CYP1B1 (23), reversed DOCA-salt-induced hypertension, cardiac and vascular hypertrophy and minimized renal dysfunction in rats (24). However, we could not exclude any nonselective effect of TMS in that study. Moreover, the role of CYP1B1 in cardiac dysfunction, and renal damage and inflammation were not examined. Therefore, to test the hypothesis that CYP1B1 contributes to cardiovascular dysfunction, and renal damage and inflammation, via increased production of ROS, and activity of neurohumoral factors and various signaling molecules in DOCA-salt-induced hypertension, this study was performed in wild type (Cyp1b1+/+) and Cyp1b1 gene disrupted (Cyp1b1−/−) mice. The results of this study provide, for the first time, strong evidence that in DOCA-salt hypertension in mice Cyp1b1 plays a major role in cardiovascular dysfunction, and renal damage and inflammation, consequent to generation of ROS and activation of one or more signaling molecules, including ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and c-Src, independent of eicosanoids.

Methods

Please see the online Data Supplement at http://hyper.ahajournals.org

Results

Cyp1b1 gene disruption minimizes DOCA-salt-induced hypertension in mice

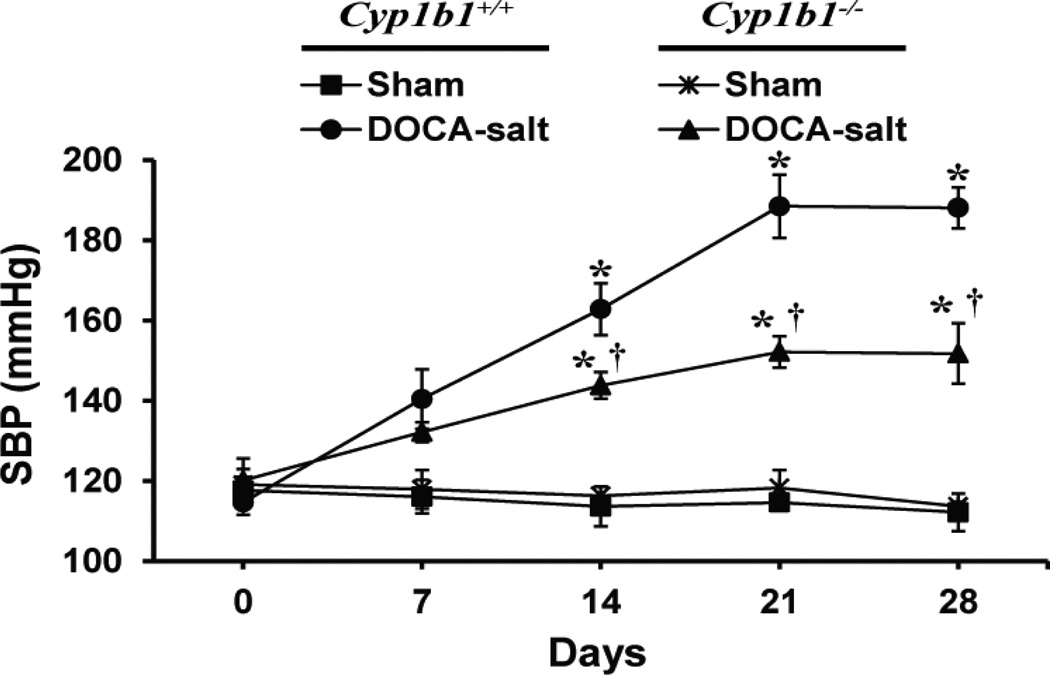

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) in Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice was measured by tail cuff method. Although this method has some limitations (25), DOCA-salt treatment caused a substantial increase in SBP in both Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice over a period of 28 days, and there was a consistent and highly significant difference in the SBP between these two groups without any change in the basal pressure in the corresponding sham controls (Figure 1). Therefore, the differences observed in SBP measured by tail cuff in Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice treated with DOCA-salt are most likely accurate.

Figure 1. Cyp1b1 gene disruption protects against DOCA-salt-induced hypertension in mice.

Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice were sham-operated or DOCA-salt-treated for 28 days as described in Methods. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was measured by tail cuff every 7 days. *P < 0.05 sham vs. corresponding value from DOCA-salt-treated animal; †P < 0.05 Cyp1b1+/+ DOCA-salt vs. Cyp1b1−/− DOCA-salt (n = 5 for all experiments and data are expressed as mean ± SEM).

DOCA-salt-induced hypertension is associated with increased CYP1B1 activity, but not expression in mice

In hearts and kidneys of DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice, CYP1B1 activity was increased compared to sham-operated Cyp1b1+/+ mice (Figures S1A, S1C, respectively). CYP1B1 protein expression was unchanged in hearts and kidneys of sham-operated and DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice (Figures S1B, S1D, respectively). Cyp1b1 gene disruption and/or DOCA-salt treatment had no effect on protein expression of other AA metabolizing enzymes in cardiac or renal homogenates (Figures S2A, S2B, respectively).

Cyp1b1 gene disruption minimizes cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension in mice

DOCA-salt treatment increased heart weight: body weight ratio (HW: BW), an indicator of cardiac hypertrophy in Cyp1b1+/+ mice; this increase was reduced in Cyp1b1−/− mice (Table S1). Echocardiography revealed impaired systolic function, as indicated by decreased fractional shortening (FS) and ejection fraction (EF) in DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice (Table 1). Impaired diastolic function, as indicated by a decrease in the ratio of tissue mitral annulus early longitudinal to atria (E′/A′) velocity was also observed in DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ but not in Cyp1b1−/− mice (Table 1). DOCA-salt treatment also resulted in an increase in the thickness of the interventricular septum, the posterior and anterior wall of the left ventricle (LV) during diastole, but not systole, and increased the LV internal diameter of Cyp1b1+/+ mice; these changes were decreased or absent in the hearts of Cyp1b1−/− mice (Table S2). DOCA-salt treatment also caused an increase in both end-diastolic volume and end-systolic volume in Cyp1b1+/+ but not Cyp1b1−/− mice, however, no difference in stroke volume was found in either sham-operated or DOCA-salt treated Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice (Table S2).

Table 1.

Cyp1b1 gene disruption protects against systolic and diastolic dysfunction associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension in mice.

| Cyp1b1+/+ | Cyp1b1−/− | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Sham | DOCA-salt | Sham | DOCA-salt |

| Systolic measures | ||||

| EF (%) | 60.83 ± 3.19 | 40.22 ± 4.03* | 54.73 ± 3.96 | 60.38 ± 6.40† |

| FS (%) | 32.10 ± 2.10 | 19.64 ± 2.23* | 28.00 ± 2.52 | 32.63 ± 4.50† |

| Diastolic measure | ||||

| E′/A′ | 1.57 ± 0.13 | 1.03 ± 0.16* | 1.60 ± 0.17 | 1.50 ± 0.18† |

Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice were sham-operated or DOCA-salt-treated for 28 days as described in Methods. Measures of systolic and diastolic function were calculated as described in Methods.

P < 0.05 sham vs. corresponding value from DOCA-salt-treated animal;

P < 0.05 Cyp1b1+/+ DOCA-salt vs. Cyp1b1−/− DOCA-salt (n = 5 for all experiments and data are expressed as mean ±SEM).

Abbreviations: EF, ejection fraction; FS, fractional shortening; E′/A′, ratio of tissue mitral annulus early longitudinal to atria velocity.

Cyp1b1 gene disruption minimizes increased renal vascular reactivity, vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy, endothelial dysfunction, and increased renal vascular resistance (RVR) associated with DOCA-salt treatment in mice

The response to phenylephrine (PE) and ET-1 of the renal artery from DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice was increased compared to sham-operated Cyp1b1+/+ mice (Figures S3A, S3B, respectively). In DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1−/− mice, no increase in response to PE was observed compared to sham-operated Cyp1b1−/− mice (Figure S3A), however, the response of the renal artery to ET-1 was increased from DOCA-salt treated Cyp1b1−/− mice compared to shamoperated Cyp1b1−/− mice; this increase was less than that seen in Cyp1b1+/+ mice (Figure S3B). The concentration of ET-1 used produced a somewhat greater magnitude of contractile response than that produced by PE, but the decrease in vascular reactivity to PE and ET-1 produced by Cyp1b1 gene disruption were not significantly different (35.39 ± 5.55 % with PE at 10−5 mol/l vs. 31.48 ± 4.56 % with ET at 10−8 mol/l, P > 0.05). The increased vascular reactivity of the renal artery from DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice correlated with an increase in media: lumen ratio, an indicator of vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy (Table S3). In the renal artery of DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1−/− mice, the media: lumen ratio was also increased, but this increase was less than that observed in Cyp1b1+/+ mice (Table S3).

DOCA-salt treatment was also associated with endothelial dysfunction of the renal artery from Cyp1b1+/+ mice, as demonstrated by a decreased relaxation response to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (ACh) compared to sham-operated Cyp1b1+/+ mice (Figure S3C). The renal artery from DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1−/− mice also displayed endothelial dysfunction, but this was improved compared to the endothelial dysfunction observed in Cyp1b1+/+ mice (Figure S3C). Endothelium-independent relaxations to sodium nitroprusside (SNP) were not different in renal arteries from mice in any of the treatment groups (Figure S3D).

Basal renal blood flow (RBF) was not different between Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice (Table S4). Furthermore, no change in RBF was observed in DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice; this lack of change in RBF despite an increase in SBP in DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice could be due to an autoregulatory response. Basal RVR was not different between Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice (Table S4). DOCA-salt treatment increased RVR in both Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice, however, this increase was reduced in Cyp1b1−/− mice compared to Cyp1b1+/+ mice (Table S4).

Cyp1b1 gene disruption minimizes increased renal vascular oxidative stress that is associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension in mice

DOCA-salt treatment caused an increase in superoxide production in the renal artery of Cyp1b1+/+ mice, as demonstrated by increased 2-hydroxyethidium (2–OHE) fluorescence compared to sham-operated animals; this increase was attenuated in the renal artery of Cyp1b1−/− mice (Figure S4).

Cyp1b1 gene disruption does not protect against renal hypertrophy, but decreases proteinuria associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension in mice

In both Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice, DOCA-salt treatment resulted in hypertrophy of the remaining kidney, as indicated by increased kidney weight: body weight ratio (KW: BW) (Table S5). DOCA-salt treatment was also associated with increased proteinuria in Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice; however, the increase in proteinuria was reduced in Cyp1b1−/− mice (Table S5).

Cyp1b1 gene disruption minimizes renal end organ damage associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension in mice

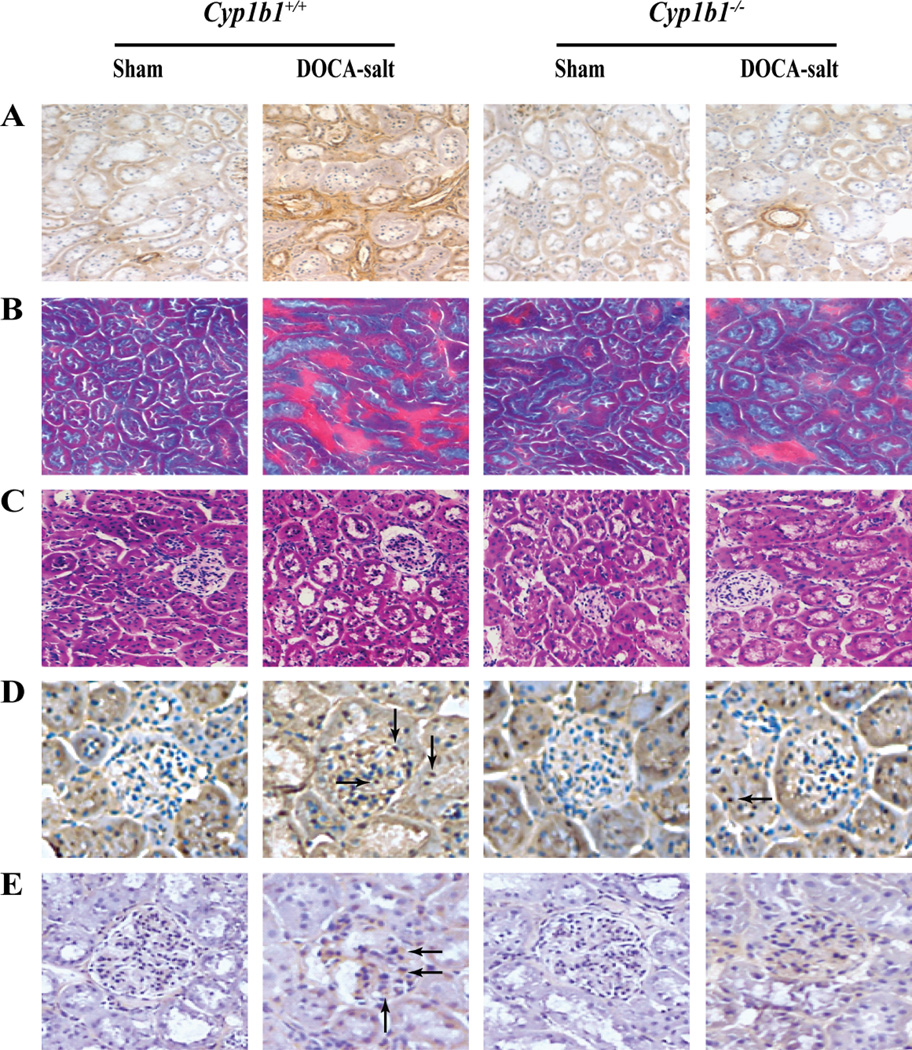

DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice displayed interstitial fibrosis, as demonstrated by increased α-smooth muscle actin staining (Figure 2A), proteinaceous cast formation (Figure 2B), tubular dilation (Figure 2C), macrophage infiltration, as indicated by increased F4/80+ cells in the glomerulus and tubules (Figure 2D), and inflammation, as demonstrated by increased CD-3+ cells in the glomerulus (Figure 2E). All of these changes were minimized in Cyp1b1−/− mice treated with DOCA-salt (Figures 2A–E, respectively).

Figure 2. Cyp1b1 gene disruption minimizes renal damage and inflammation associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension in mice.

Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice were sham-operated or DOCA-salt-treated for 28 days as described in Methods. Increased interstitial staining of α-smooth muscle actin (A), an indicator of interstitial fibrosis, was observed in kidney sections from DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice that was minimized in Cyp1b1−/− mice. (B) Gomori trichrome staining revealed increased proteinaceous cast formation (intense red staining) in the interstitial space of kidneys from DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice, which was decreased in Cyp1b1−/− mice. (C) Increased tubular dilation, observed in the kidneys of DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice was reduced in Cyp1b1−/− mice. F4/80+ cells, indicating macrophage infiltration (D, arrows) and CD-3+ cells, indicating T lymphocyte infiltration (E, arrows), are accumulated in the glomeruli of DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice; very few F4/80+ and CD-3+ cells were observed in glomeruli and tubules of DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1−/− mice.

Cyp1b1 gene disruption minimizes increased plasma levels of catecholamines, ET-1, and AVP associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension

Basal plasma levels of catecholamines, ET-1, and AVP were not different in Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice (Table S6). DOCA-salt treatment increased plasma levels of catecholamines, ET-1, and AVP in Cyp1b1+/+ mice; these increases were reduced or absent in DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1−/− mice (Table S6).

DOCA-salt-induced hypertension is not associated with changes in cardiac or renal levels of eicosanoids in Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice

Basal levels of eicosanoids in the hearts and kidneys of Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice were not different (Table S7). DOCA-salt treatment did not alter cardiac or renal levels of any of the eicosanoids measured in Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice (Table S7).

Cyp1b1 gene disruption minimizes increased cardiac and renal ROS production, NADPH oxidase activity, and NOX1 expression associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension

DOCA-salt treatment increased cardiac and renal superoxide production in Cyp1b1+/+ mice, as demonstrated by an increase in 2-OHE fluorescence; this increase was attenuated in the hearts and kidneys of Cyp1b1−/− mice (Figures S5A, S5D, respectively). The increase in superoxide production in DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice was associated with an increase in cardiac and renal NADPH oxidase activity (Figures S5B, S5E, respectively) and protein expression of NOX1 (Figures S5C, S5F, respectively); these increases were also attenuated in hearts and kidneys of Cyp1b1−/− mice treated with DOCA-salt (Figures S5B, S5C and S5E, S5F, respectively).

Cyp1b1 gene disruption minimizes increased cardiac and renal activities of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and c-Src associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension in mice

In hearts and kidneys of Cyp1b1+/+ mice, DOCA-salt treatment increased the activities of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and c-Src, as measured by phosphorylation of these kinases; this was significantly reduced in the heart and kidney of Cyp1b1−/− mice treated with DOCA-salt (Figures S6A–C, S6D–, respectively).

Discussion

This study demonstrates for the first time that CYP1B1 plays a crucial role in the cardiovascular dysfunction, and renal damage and inflammation associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension, as a result of ROS production via increased activity of NADPH oxidase, and activation of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and c-Src in mice. Administration of DOCA-salt in Cyp1b1+/+ mice increased SBP, and CYP1B1 activity in the heart and kidney without altering expression levels or shifting the CYP1B1 protein bands on western blots. The mechanism by which DOCA-salt treatment increases CYP1B1 activity, which could be due to a biochemical modification of this enzyme or involvement of some other endogenous factor(s), including increased P450 reductase and/or NADPH levels remains to be determined.

DOCA-salt treatment caused cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction in Cyp1b1+/+ mice as indicated by: a) increased HW: BW ratio; b) increased thickness of the interventricular septum, posterior and anterior walls of the LV during diastole, and increased LV internal diameter; c) increased end diastolic and end systolic volume; d) impaired diastolic function as indicated by decrease E’/A ratio; and e) impaired systolic function as indicated by decreased FS and EF. Our finding that Cyp1b1 gene disruption in mice prevented or minimized these cardiac changes produced by DOCA-salt, suggests that CYP1B1 is required for the cardiac dysfunction associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension. Although an increase in BP caused by DOCA-salt was reduced, it was not prevented in Cyp1b1−/− mice, suggesting that the cardiac dysfunction in these mice is, in part, independent of BP as reported by other investigators (26, 27). Our finding that a component of DOCA-salt-induced hypertension is resistant to Cyp1b1 gene disruption in mice, suggests that factors other than CYP1B1 also contribute to the development of hypertension in this model. Recently, it has been shown that mice lacking leukocyte-type 12/15 LO (Alox15) are resistant to DOCA-salt- and l-NAME-induced hypertension, and that macrophage and not vascular Alox 15 is required for l-NAME-induced hypertension (28). Whether these mice are also resistant to the cardiovascular dysfunction and infiltration of macrophages and T cells associated with DOCA-salt hypertension is not known. In our study, Cyp1b1 gene disruption did alter the expression of other CYP isoforms, COX1, COX2, or 12/15 LO in the hearts or kidneys of DOCA salt-treated mice.

DOCA-salt-induced hypertension is also associated with increased vascular reactivity and endothelial dysfunction (29, 30). Our findings that: a) increased response of the renal artery to PE and ET-1; b) hypertrophy, as indicated by increased media: lumen ratio; c) endothelial dysfunction, as indicated by the loss of ACh-, but not SNP-induced relaxation; and d) increased RVR in DOCA-salt treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice were minimized or abolished in Cyp1b1−/− mice, also support the role of CYP1B1 in these pathophysiological changes that may also contribute to DOCA-salt-induced hypertension.

DOCA-salt treatment in Cyp1b1+/+ mice also caused: a) hypertrophy of the remaining kidney, as observed by increased KW: BW ratio; b) marked proteinuria; c) interstitial fibrosis, as indicated by increased accumulation of interstitial α-smooth muscle actin, d) proteinaceous cast formation; e) tubular dilation; and f) inflammation, as shown by increased infiltration of F4/80+ macrophages and CD-3+ lymphocytes in the glomerulus. The demonstration that these pathophysiological changes, except hypertrophy of the kidney, were minimized in Cyp1b1−/− mice treated with DOCA-salt, suggest a crucial role of CYP1B1 in renal dysfunction, end organ damage, and inflammation associated with DOCA-salt hypertension. Moreover, it appears that the renal hypertrophy caused by DOCA-salt treatment is not the result of these CYP1B1-dependent pathophysiological changes.

The mechanism by which CYP1B1 promotes DOCA-salt-induced hypertension, cardiovascular hypertrophy and dysfunction, endothelial and renal dysfunction, end organ damage and inflammation, could be due to increased release of AA consequent to activation of phospholipase A2 by catecholamines, AVP, and/or ET-1 (5–7). AA can be metabolized by CYP1B1 in vitro into various eicosanoids including 12- and 20-HETE and EETs (18), which contribute to pro- and anti-hypertensive mechanisms, respectively (31–33). Moreover, metabolism of AA by CYP1B1 in VSMCs results in generation of ROS (19) that have been implicated in various models of experimental hypertension including DOCA-salt hypertension and associated pathophysiological changes (13–17). In a previous study, we found that infusion of Ang II for 13 and 28 days increased the levels of 12- and 20-HETE in the kidneys of Cyp1b1+/+, but not Cyp1b1−/− mice (22). In DOCA-salt-induced hypertension, urinary excretion of 20-HETE is also increased; this increase is mediated by ET-1, and both 20-HETE and ET-1 contribute to hypertension (34). In contrast, other studies have shown that renal tissue levels of 20-HETE are reduced and this is associated with decreased expression of CYP4A in DOCA-salt hypertension (35, 36). 20-HETE exerts prohypertensive effects by causing renal vascular constriction but exerts an antihypertensive effect by increasing Na+ and water excretion (32). In the present study, DOCA-salt treatment did not alter levels of any HETEs and EETs measured in the hearts or kidneys of Cyp1b1+/+ and Cyp1b1−/− mice. Moreover, Cyp1b1 gene disruption and/or DOCA-salt treatment did not alter cardiac or renal expression of other CYP isoforms or AA metabolizing enzymes. Currently, we have no explanation for these discrepancies. However, in view of the unchanged levels of eicosanoids determined in this study, it is unlikely that they contribute to the increased levels of catecholamines, vasopressin, or ET-1 and the end organ damage produced by DOCA-salt.

Previously, we have reported that AA- and Ang II-induced activation of NADPH oxidase and ROS production is dependent on CYP1B1 activity (19). Therefore, it is possible that ROS generated via CYP1B1 could mediate the cardiovascular and renal dysfunction, end organ damage and development of hypertension caused by DOCA-salt (37). Supporting this view was our demonstration that ROS production in the heart, renal artery, and kidney, and NADPH oxidase activity and expression of NOX1 measured in the heart and kidney, were increased in DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice but were minimized in these tissues of Cyp1b1−/− mice. Whether other NOX isoforms contribute to the increase in NADPH oxidase activity that is dependent on CYP1B1 remains to be determined. Our demonstration that the levels of catecholamines, AVP, and ET-1 that were increased in DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice were reduced in Cyp1b1−/− mice, raises the possibility that CYP1B1 via generation of ROS in the brain might also amplify sympathetic activity, and release of catecholamines, AVP, and ET-1, that in turn further stimulate ROS production in cardiovascular and/or renal tissues (38–40). Cyp1b1 mRNA is present in different brain regions (41), and ROS are known to stimulate both central and peripheral sympathetic activity and ET-1 production (42–45).

Ang II-, DOCA-salt- or aldosterone-induced hypertension and endothelial dysfunction, increased oxidative stress, cardiovascular and/or renal damage have been reported to be associated with increased activation and/or infiltration of immune cells (46–49). These effects are diminished in severe combined immunodeficiency (46), by depletion of macrophages (47, 48), or in Rag-1−/− mice (49) or by adaptive transfer of T-lymphocyte regulatory cells (CD4+ and CD25+ cell) (50, 51). The presence of CYP1B1 in macrophages and T lymphocytes (52, 53) together with our demonstration that infiltration of macrophages and T lymphocytes in the kidney of DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice were reduced in Cyp1b1−/− mice, raises the possibility that lipid peroxides and/or ROS generated from AA via CYP1B1 in macrophages and T lymphocytes might be involved in their activation and infiltration in renal tissues.

ROS generated via CYP1B1 could cause cardiovascular and renal dysfunction, end organ damage, and inflammation in DOCA-salt-treated Cyp1b1+/+ mice by activating various signaling molecules, including ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and c-Src (54–56). Evidence supporting this notion was our observation that DOCA-salt treatment increased the activity of these signaling molecules in hearts and kidneys of Cyp1b1+/+ mice, but not in these tissues of Cyp1b1−/− mice. Dyshomeostasis of divalent cations has also been demonstrated to result in oxidative stress and cardiac damage caused by aldosterone and salt (57). Whether CYP1B1 is involved in ROS production caused by divalent cation dyshomeostasis remains to be determined.

In conclusion, the present study shows that CYP1B1 plays a significant role in the cardiovascular and renal dysfunction, end organ damage and inflammation, and hypertension caused by DOCA-salt, via generation of ROS by stimulation of NADPH oxidase, and activation of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and c-Src in mice. Furthermore, CYP1B1 could serve as a novel target for the development of agents that ameliorate hypertension and pathophysiological changes associated with hyperaldosteronism and salt.

Supplementary Material

Perspectives.

The present study demonstrates a pivotal role of CYP1B1 in the cardiovascular and renal dysfunction, end organ damage and inflammation associated with DOCA-salt hypertension. Moreover, it reveals an important role of CYP1B1 in the regulation of catecholamine, AVP, and ET-1 levels that contribute to hypertension, and associated pathophysiological changes produced by DOCA-salt treatment. The increased levels of these neurohumoral factors and the pathophysiological changes in DOCA-salt hypertension are most likely caused by activation of NADPH oxidase and ROS production by non-HETE AA metabolites via CYP1B1, and activation of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK and c-Src. These observations together with our previous work on Ang II-induced hypertension (20–22), compels one to consider CYP1B1 as a potential therapeutic target. Selective inhibitors of this enzyme will be useful for the treatment of cardiovascular and renal dysfunction and end organ damage associated with hypertension.

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New?

Demonstration that CYP1B1 is indispensable for cardiovascular and renal dysfunction, end organ damage, and inflammation associated with DOCA-salt hypertension.

CYP1B1 plays an important role in the regulation of catecholamines, AVP, and ET-1 that are known to contribute to hypertension and associated pathophysiological changes produced by DOCA-salt.

NADPH oxidase activity, generation of ROS, and activation of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and c-Src in DOCA-salt hypertension are dependent on CYP1B1 activity.

What is Relevant?

This study advances our knowledge of the mechanism underlying pathogenesis of hypertension and demonstrates CYP1B1 as a potential therapeutic target for the development of agents to treat cardiovascular and renal dysfunction, and end organ damage associated with excess mineralocorticoid-salt hypertension.

Summary

CYP1B1 plays a significant role in cardiovascular dysfunction, renal damage and inflammation, and increased levels of catecholamines, AVP, and ET-1 associated with DOCA-salt hypertension in mice, most likely as a result of generation of ROS and activation of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and c-Src independent of eicosanoids.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David L. Armbruster for editorial assistance.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, grants R01-HL-19134–37 (K.U.M) and R01-HL-103673 (W.B.C). L.J.A. was supported by a summer student fellowship from the American Society of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Schenk J, McNeill JH. The pathogenesis of DOCA-salt hypertension. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1992;27:161–170. doi: 10.1016/1056-8719(92)90036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crofton JT, Share L, Shade RE, Lee-Kwon WJ, Manning M, Sawyer WH. The importance of vasopressin in the development and maintenance of DOC-salt hypertension in the rat. Hypertension. 1979;1:31–38. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.1.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Champlain J, Bouvier M, Drolet G. Abnormal regulation of the sympathoadrenal system in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1987;65:1605–1614. doi: 10.1139/y87-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiffrin EL, Sventek P, Li J-S, Turgeon A, Reudelhuber T. Antihypertensive effect of an endothelin receptor antagonist in DOCA-salt spontaneously hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115:1377–1381. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonventre JV, Swidler M. Calcium dependency of prostaglandin E2 production in rat glomerular mesangial cells. Evidence that protein kinase C modulates the Ca2+-dependent activation of phospholipase A2. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:168–176. doi: 10.1172/JCI113566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muthalif MM, Benter IF, Uddin MR, Malik KU. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIα mediates activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and cytosolic phospholipase A2 in norepinephrine-induced arachidonic acid release in rabbit aortic smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30149–30157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.30149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trevisi L, Bova S, Cargnelli G, Ceolotto G, Luciani S. Endothelin-1-induced arachidonic acid release by cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation in rat vascular smooth muscle via extracellular signal-regulated kinases pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64:425–431. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sacerdoti D, Escalante B, Abraham NG, McGiff JC, Levere RD, Schwartzman ML. Treatment with tin prevents the development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Science. 1989;243:388–390. doi: 10.1126/science.2492116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasjletti A, Arthur C. Corcoran Memorial Lecture. The role of eicosanoids in angiotensin-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 1998;31:194–200. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su P, Kaushal KM, Kroetz DL. Inhibition of renal arachidonic acid ω-hydroxylase activity with ABT reduces blood pressure in the SHR. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1998;275:R426–R438. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.2.R426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muthalif MM, Benter IF, Khandekar Z, Gaber L, Estes A, Malik S, Parmentier J-H, Manne V, Malik KU. Contribution of Ras GTPase/MAP kinase and cytochrome P450 metabolites to deoxycorticosterone-salt–induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;35:457–463. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muthalif MM, Karzoun NA, Gaber L, Khandekar Z, Benter IF, Saeed AE, Parmentier J-H, Estes A, Malik KU. Angiotensin II–induced hypertension. Contribution of Ras GTPase/mitogen-activated protein kinase and cytochrome P450 metabolites. Hypertension. 2000;36:604–609. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong H-J, Hsiao G, Cheng T-H, Yen M-H. Supplementation with tetrahydrobiopterin suppresses the development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2001;38:1044–1048. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.095331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beswick RA, Dorrance AM, Leite R, Webb RC. NADH/NADPH oxidase and enhanced superoxide production in the mineralocorticoid hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 2001;38:1107–1111. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.093423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landmesser U, Dikalov S, Price SR, McCann L, Fukai T, Holland SM, Mitch WE, Harrison DG. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1201–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI14172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sánchez M, Galisteo M, Vera R, Villar IC, Zarzuelo A, Tamargo J, Pérez-Vizcaíno F, Duarte J. Quercetin downregulates NADPH oxidase, increases eNOS activity and prevents endothelial dysfunction in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2006;24:75–84. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000198029.22472.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bao W, Behm DJ, Nerurkar SS, Ao Z, Bentley R, Mirabile RC, Johns DG, Woods TN, Doe CPA, Coatney RW, Ohlstein JF, Douglas SA, Willette RN, Yue T-L. Effects of p38 MAPK inhibitor on angiotensin II-dependent hypertension, organ damage, and superoxide anion production. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;49:362–368. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318046f34a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choudhary D, Jansson I, Stoilov I, Sarfarazi M, Schenkman JB. Metabolism of retinoids and arachidonic acid by human and mouse cytochrome P450 1B1. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:840–847. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.8.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yaghini FA, Song CY, Lavrentyev EN, Ghafoor HUB, Fang XR, Estes AM, Campbell WB, Malik KU. Angiotensin II–induced vascular smooth muscle cell migration and growth are mediated by cytochrome P450 1B1–dependent superoxide generation. Hypertension. 2010;55:1461–1467. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jennings BL, Sahan-Firat S, Estes AM, Das K, Farjana N, Fang XR, Gonzalez FJ, Malik KU. Cytochrome P450 1B1 contributes to angiotensin II–induced hypertension and associated pathophysiology. Hypertension. 2010;56:667–674. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.154518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jennings BL, Anderson LJ, Estes AM, Fang XR, Song CY, Campbell WB, Malik KU. Involvement of cytochrome P-450 1B1 in renal dysfunction, injury, and inflammation associated with angiotensin II-induced hypertension in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F408–F420. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00542.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jennings BL, Anderson LJ, Estes AM, Yaghini FA, Fang XR, Porter J, Gonzalez FJ, Campbell WB, Malik KU. Cytochrome P450 1B1 contributes to renal dysfunction and damage caused by angiotensin II in mice. Hypertension. 2012;59:348–354. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.183301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chun Y-J, Kim S, Kim D, Lee S-K, Guengerich FP. A new selective and potent inhibitor of human cytochrome P450 1B1 and its application to antimutagenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8164–8170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sahan-Firat S, Jennings BL, Yaghini FA, Song CY, Estes AM, Fang XR, Farjana N, Khan AI, Malik KU. 2,3′,4,5′-Tetramethoxystilbene prevents deoxycorticosterone-salt-induced hypertension: contribution of cytochrome P-450 1B1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1891–H1901. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00655.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurtz TW, Griffin KA, Bidani AK, Davisson RL, Hall JE. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals. Part 2: blood pressure measurement in experimental animals. A statement for professionals from the subcommittee of professional and public education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005;45:299–310. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150857.39919.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karam H, Heudes D, Hess P, Gonzales M-F, Löffler B-M, Clozel M, Clozel J-P. Respective role of humoral factors and blood pressure in cardiac remodeling of DOCA hypertensive rats. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;31:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q, Domenighetti AA, Pedrazzini T, Burnier M. Potassium supplementation reduces cardiac and renal hypertrophy independent of blood pressure in DOCA/salt mice. Hypertension. 2005;46:547–554. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000178572.63064.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kriska T, Cepura C, Magier D, Siangjong L, Gauthier KM, Campbell WB. Mice lacking macrophage 12/15-lipoxygenase are resistant to experimental hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2428–H2438. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01120.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berecek KH, Murray RD, Gross F, Brody MJ. Vasopressin and vascular reactivity in the development of DOCA hypertension in rats with hereditary diabetes insipidus. Hypertension. 1982;4:3–12. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.4.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Somers MJ, Mavromatis K, Galis ZS, Harrison DG. Vascular superoxide production and vasomotor function in hypertension induced by deoxycorticosterone acetate–salt. Circulation. 2000;101:1722–1728. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.14.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGiff JC, Quilley J. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids and blood pressure. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2001;10:231–237. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200103000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roman RJ. P-450 Metabolites of arachidonic acid in the control of cardiovascular function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:131–185. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imig JD. Epoxide hydrolase and epoxygenase metabolites as therapeutic targets for renal diseases. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F496–F503. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00350.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oyekan AO, McAward K, Conetta J, Rosenfeld L, McGiff JC. Endothelin-1 and CYP450 arachidonate metabolites interact to promote tissue injury in DOCA-salt hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1999;276:R766–R775. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.3.R766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Honeck H, Gross V, Erdmann B, Kärgel E, Neunaber R, Milia AF, Schneider W, Luft FC, Schunck W-H. Cytochrome P450–dependent renal arachidonic acid metabolism in deoxycorticosterone acetate–salt hypertensive mice. Hypertension. 2000;36:610–616. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Y, Luo P, Chang H-H, Huang H, Yang T, Dong Z, Wang C-Y, Wang M-H. Clofibrate attenuates blood pressure and sodium retention in DOCA-salt hypertension. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1040–1048. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin L, Beswick RA, Yamamoto T, Palmer T, Taylor TA, Pollock JS, Pollock DM, Brands MW, Webb RC. Increased reactive oxygen species contributes to kidney injury in mineralocorticoid hypertensive rats. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;57:343–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Intengan HD, He G, Schiffrin EL. Effect of vasopressin antagonism on structure and mechanics of small arteries and vascular expression of endothelin-1 in deoxycorticosterone acetate–salt hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1998;32:770–777. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.4.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sedeek MH, Llinas MT, Drummond H, Fortepiani L, Abram SR, Alexander BT, Reckelhoff JF, Granger JP. Role of reactive oxygen species in endothelin-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:806–810. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000084372.91932.BA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollock DM. Endothelin, angiotensin, and oxidative stress in hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:477–480. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000158262.11935.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rieder CRM, Ramsden DB, Williams AC. Cytochrome P450 1B1 mRNA in the human central nervous system. J Clin Pathol: Mol Pathol. 1998;51:138–142. doi: 10.1136/mp.51.3.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu H, Fink GD, Galligan JJ. Nitric oxide-independent effects of tempol on sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in DOCA-salt rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H885–H892. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00134.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campese VM, Ye S, Zhong H, Yanamadala V, Ye Z, Chiu J. Reactive oxygen species stimulate central and peripheral sympathetic nervous system activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H695–H703. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00619.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gayen JR, Zhang K, RamachandraRao SP, Mahata M, Chen Y, Kim H-S, Naviaux RK, Sharma K, Mahata SK, O'Connor DT. Role of reactive oxygen species in hyperadrenergic hypertension: biochemical, physiological, and pharmacological evidence from targeted ablation of the chromogranin A (Chga) gene. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:414–425. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.924050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen H-C, Guh J-Y, Shin S-J, Tsai J-H, Lai Y-H. Reactive oxygen species enhances endothelin-1 production of diabetic rat glomeruli in vitro and in vivo. J Lab Clin Med. 2000;135:309–315. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2000.105616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crowley SD, Song Y-S, Lin EE, Griffiths R, Kim H-S, Ruiz P. Lymphocyte responses exacerbate angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1089–R1097. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00373.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Ciuceis C, Amiri F, Brassard P, Endemann DH, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Reduced vascular remodeling, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress in resistance arteries of angiotensin II–infused macrophage colony-stimulating factor–deficient mice: evidence for a role in inflammation in angiotensin-induced vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2106–2113. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000181743.28028.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ko EA, Amiri F, Pandey NR, Javeshghani D, Leibovitz E, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Resistance artery remodeling in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension is dependent on vascular inflammation: evidence from m-CSF-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1789–H1795. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01118.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II–induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kvakan H, Kleinewietfeld M, Qadri F, Park J-K, Fischer R, Schwarz I, Rahn H-P, Plehm R, Wellner M, Elitok S, Gratze P, Dechend R, Luft FC, Muller DN. Regulatory T cells ameliorate angiotensin II–induced cardiac damage. Circulation. 2009;119:2904–2912. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.832782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kasal DA, Barhoumi T, Li MW, Yamamoto N, Zdanovich E, Rehman A, Neves MF, Laurant P, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent aldosterone-induced vascular injury. Hypertension. 2012;59:324–330. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.181123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ward JM, Nikolov NP, Tschetter JR, Kopp JB, Gonzalez FJ, Kimura S, Siegel RM. Progressive glomerulonephritis and histiocytic sarcoma associated with macrophage functional defects in CYP1B1-deficient mice. Toxicol Pathol. 2004;32:710–718. doi: 10.1080/01926230490885706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spencer DL, Masten SA, Lanier KM, Yang X, Grassman JA, Miller CR, Sutter TR, Lucier GW, Walker NJ. Quantitative analysis of constitutive and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced cytochrome P450 1B1 expression in human lymphocytes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:139–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheng T-H, Shih N-L, Chen C-H, Lin H, Liu J-C, Chao H-H, Liou J-Y, Chen Y-L, Tsai H-W, Chen Y-S, Chen C-F, Chen J-J. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in reactive oxygen species-mediated endothelin-1-induced β-myosin heavy chain gene expression and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Biomed Sci. 2005;12:123–133. doi: 10.1007/s11373-004-8168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim N-H, Rincon-Choles H, Bhandari B, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE, Gorin Y. Redox dependence of glomerular epithelial cell hypertrophy in response to glucose. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F741–F751. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00313.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Madamanchi NR, Moon S-K, Hakim ZS, Clark S, Mehrizi A, Patterson C, Runge MS. Differential activation of mitogenic signaling pathways in aortic smooth muscle cells deficient in superoxide dismutase isoforms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:950–956. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000161050.77646.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weber KT, Bhattacharya SK, Newman KP, Soberman JE, Ramanathan KB, McGee JE, Malik KU, Hickerson WL. Stressor states and the cation crossroads. J Am Coll Nutr. 2010;29:563–574. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2010.10719895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.