Abstract

Aims

This study sought to develop and begin validation of an indirect screener for identification of drug use during pregnancy, without reliance on direct disclosure.

Design

Women were recruited from their hospital rooms after giving birth. Participation involved (a) completing a computerized assessment battery containing three types of items: direct (asking directly about drug use), semi-indirect (asking only about drug use prior to pregnancy) and indirect (with no mention of drug use), and (b) providing urine and hair samples. An optimal subset of indirect items was developed and cross-validated based on ability to predict urine/hair test results.

Setting

Obstetric unit of a university-affiliated hospital in Detroit.

Participants

400 low-income, African American, post-partum women (300 in the developmental sample and 100 in the cross-validation sample); all available women were recruited without consideration of substance abuse risk or other characteristics.

Measurements

Women first completed the series of direct and indirect items using a Tablet PC; they were then asked for separate consent to obtain urine and hair samples that were tested for evidence of illicit drug use.

Findings

In the cross-validation sample, the brief screener consisting of 6 indirect items predicted toxicology results more accurately than direct questions about drug use (area under the ROC curve = .74, p < .001). Traditional direct screening questions were highly specific but identified only a small minority of women who used drugs during the last trimester of pregnancy.

Conclusions

Indirect screening may increase the accuracy of mothers’ self-reports of prenatal drug use.

Under-reporting of illicit drug use is a well-established phenomenon (1, 2). It is particularly likely in settings where drug use is stigmatized or can lead to negative consequences; this includes the perinatal period, where failure to disclose drug use is common (3-7). This hesitancy to disclose drug use among pregnant or post-partum women is a major obstacle to the provision of appropriate interventions with this important population.

Existing screeners for drug use risk are highly face-valid, and thus vulnerable to under-reporting (8). Despite demonstration of good sensitivity and specificity in some studies (9), direct screeners such as the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST; 10) have primarily been validated against structured diagnostic interviews in treatment settings. Validating self-report against self-report in this way leaves open the possibility that respondents may simply deny drug use in both conditions. The validity of such screeners with non-treatment seeking samples, and in predicting the results of toxicology tests for drug use, is less clear (11).

This study was developed to meet the need for a rigorously developed indirect screener for drug use in the perinatal period. Specifically, we sought to (a) develop a screening tool that does not itself refer to drug use, using toxicology results as the criterion measure; and (b) evaluate the concurrent validity of this screener against more traditional approaches in an additional validation sample. We predicted that on cross-validation, the newly developed indirect screener (called the Wayne Indirect Drug Use Screener, or WIDUS) would show similar overall accuracy and greater sensitivity than alternative approaches.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 400 women (300 in the developmental sample, recruited first, and 100 in the subsequently recruited validation sample) who had recently given birth at an obstetric hospital in Detroit. Women were excluded if they had not slept since giving birth, were distressed about the health of their newborn, did not understand English, were sleeping, or chose not to provide urine and hair samples.

Measures

Indirect items

Indirect items were developed following a literature review of possible correlates of illicit drug use. Examples include behavioral correlates such as smoking (12); medical correlates such as chronic pain (13); mental health correlates such as depression or post-traumatic stress (14); demographic correlates such as marital status (15); experiential correlates such as exposure to violence (16); and neurobehavioral disinhibition (17). Using these and other areas as a guide, a pool of potential items was subjected to review by a panel of four experts (all of whom were experts in substance use among women, and/or test development) who rated each item on a 1-5 scale for clarity, acceptability, and stigma. Items were rated on the same dimensions by a panel of six pregnant women with a history of drug use. These scores were summed to create an overall rating; items scoring more than two standard deviations below the mean were removed from consideration. All items used a true-false response set to aid in comprehensibility. Items retained for further analysis had a below-9th grade reading level and did not themselves refer to drug use, sexual behavior, or drug use by peers. The initial pool included 74 indirect items.

Direct items

The DAST-10 (18), a widely used 10-item measure of past year drug use consequences, was used as the primary direct measure of drug use. In addition to the DAST-10, direct questions regarding drug use during pregnancy were also administered to participants in the cross-validation sample (see below). These items referred separately to marijuana and other drug use in the past three months.

Semi-indirect items

All participants were asked a brief series of semi-indirect items asking about drug use in the three months prior to becoming pregnant rather than during pregnancy. These items were modifications of the first two items of the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (19, 20).

Urine analysis

Urine samples were tested using the Redwood BioTech RediCup®, which provides instant quantitative results for a range of drugs simultaneously. We recorded evidence of cocaine, marijuana, or stimulant (amphetamine, methamphetamine, or MDMA) use. Evidence of opiate or sedative metabolites was not considered, given the frequency with which these substances are administered during childbirth.

Hair analysis

Urine analysis is a sensitive test for recent drug use, but has a short window of detection. We therefore also obtained 1.5 inch hair samples, which provided an approximate 90-day window of detection. Hair samples were tested by Psychemedics, Inc., for evidence of marijuana, cocaine, opiates, methamphetamines, MDMA, and PCP, with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry confirmation of positive results. There is a delay of five to seven days between drug use and the appearance of affected hair above the scalp, allowing evidence of opiates in hair to be considered pre-hospitalization drug use.

Procedures

Participants were recruited between February of 2008 and September of 2009. Data collection took place in two steps. In step one, participants were recruited from their hospital rooms after giving birth. All participants answered questions using an Audio-Computer Assisted Self Interview (ACASI) approach. Participants completed the computerized assessment anonymously and without knowledge of the pending request for biological samples in order to avoid a “bogus pipeline” response set (21). In step two, participants were asked to provide hair and urine samples. Participants provided informed consent for assessment and sample collection separately. They were given a small gift bag for completing the ACASI measures, and a $75 Target gift card for providing biological samples.

These two steps were conducted in each of two phases. In Phase I, the developmental phase, data collection continued until 300 participants had completed the measures and provided a hair sample (293 also provided a urine sample). The draft WIDUS was then derived from the initial set of 74 indirect items. The draft WIDUS was then tested in Phase II, the cross-validation phase, for an additional 100 participants. The two samples were thus recruited consecutively, with a break to identify the top-performing items and reduce the investigational measure from 74 to 34 items (in order to reduce set effects). Recruitment and data collection procedures for the two phases were otherwise identical.

Data Analysis

Results from hair and urine analyses were used as the gold standard criterion; evidence of drug use from either source resulted in classification as positive, with the exception of opiate- or sedative-positive urine tests. A total of 25 hair samples contained insufficient hair for gas chromatography/mass spectrometry confirmation; urine test results were used for these cases. Similarly, urine tests were invalid for 7 participants; hair test results were used for these cases. In a series of planned analyses, we used this gold standard to evaluate the concurrent validity of the WIDUS, as well as of direct approaches, in terms of overall accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value (PPV and NPV), and linear association with drug use.

The overall sample of 74 indirect items served as the pool for creation of the draft WIDUS. Item reduction to derive the WIDUS followed a previously validated process (22). Notably, scales are designed to evaluate the existence or severity of an underlying theoretical construct, whereas indexes—a type of measure of which screeners are a subtype—are designed purely for prediction of a current or future state (23). Measure characteristics such as internal consistency are highly relevant to scales, but not to indexes, and were therefore not considered. Item reduction steps were as follows:

Items with an endorsement frequency of less than 10% or greater than 90% were dropped to prevent inconsistent performance across samples.

We selected the 30 items with the highest association in individual contingency table analysis against the gold standard described above (using tetrachoric correlation coefficients because of the implied continuity of drug use as well as of the risk factors being measured). The number 30 was chosen in order to retain an N:k ratio of at least 10.

These 30 items were subjected to multivariate Logistic Regression analysis, using simultaneous entry, in order to select items based on performance in the context of other remaining items. This process allowed for removal of items that overlapped or cancelled each other out in the multivariate context.

As in the item reduction process outlined by Liu and Jin (22), items with negative beta weights in the multivariate context were dropped, as were items with negative beta weights in subsequent iterations until all items showed associations in the expected direction.

As also outlined by Liu and Jin (22), and in order to avoid subjectivity, the final set of items with positive beta weights was then subjected to logistic regression with forward selection using the likelihood ratio.

Cross-validation was then carried out with the additional sample of 100 participants (not part of the developmental sample).

Results

A total of 542 women were approached for this study. During pre-screening, 12 declined to participate, 26 were under 18, and 79 were ineligible because of medical staff's need for access, uncontrolled pain, inability to speak English, or recent use of narcotic pain medication. Only one participant who met all initial criteria chose not to complete the self-report measures. Of the remaining 423 participants, 23 chose not to provide hair or urine samples. Thus, of the 423 who completed the self-report measures, 94.6% (400) also provided biological samples for testing and were thus included in the present analyses. Of the 400 participants providing hair and/or urine samples, three provided incomplete responses to the self-report measures. Across all participants, hair and urine test results overlapped substantially (χ2 [1] = 67.1, p < .001), but each also contributed unique identification (Phi coefficient = .42)

Among the developmental sample of 300 women, all of whom were recruited consecutively prior to recruitment of the cross-validation sample, approximately one-quarter reported use of drugs in the months prior to pregnancy. Nearly all reported current receipt of some form of public assistance (such as food stamps and Medicaid health insurance for the current pregnancy), and nearly all were African-American (see Table 1). Characteristics for the cross-validation sample of 100 women were similar, with the two subgroups differing primarily in rate of testing positive for illicit drug use: 66 participants from the developmental sample (22%) were positive for drug use, whereas 41 participants in the validation sample (41%) tested positive (χ2 [1] = 13.8, p < .001). In addition, a higher proportion of cross-validation participants were 34 or older (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at baseline, by condition

| Total sample N (%) | Developmental sample N (%) | Validation sample N (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | 83 (20.8) | 58 (19.3) | 25 (25.0%) | .226 |

| African-American | 366 (91.5) | 272 (90.7) | 94 (94.0) | .301 |

| Drug use positive (hair/urine) | 107 (26.8) | 66 (22.0) | 41 (41.0) | <.001 |

| Self-report of any drug use in 3 months prior to pregnancy | 104 (26.2) | 77 (25.9) | 27 (27.0) | .833 |

| T-ACE alcohol screen positive | 111 (28.0) | 88 (29.6) | 23 (23.0) | .201 |

| Current receipt of public assistance | 342 (85.5) | 256 (86.2) | 86 (86.0) | .961 |

| Currently working ≥ 20 hours/week | 157 (39.6) | 125 (42.1) | 32 (32.0) | .085 |

| HS graduate or GED | 232 (58.0) | 204 (68.0) | 72 (72.0) | .454 |

| Has private health insurance | 143 (36.0) | 110 (37.0) | 33 (33.0) | .467 |

| Age 18-25 | 236 (59.2) | 177 (59.2) | 59 (59.0) | 1.00 |

| Age 26-33 | 118 (29.5) | 96 (32.1) | 22 (22.0) | .058 |

| Age 34 + | 45 (11.3) | 26 (8.7) | 19 (19.0) | .005 |

Note. Significance values are derived from Chi-square analyses (df =1) for all sample characteristics.

Under-reporting in the study sample

Under-reporting was substantial in this sample, despite the use of computer-based self-report and the provision of anonymity. Of participants testing positive for drug use, only 57 (54.8%) reported drug use in the three months prior to pregnancy. In the cross-validation sample, only 10 drug-positive participants (10%) reported drug use in the 3 months prior to giving birth.

WIDUS item reduction results

In step one of item reduction, 27 items were dropped because of endorsement rates greater than 90% or less than 10%. Tetrachoric correlation coefficients were then calculated on the remaining 47 items, and the top 30 were retained. Items with a negative beta weight were then removed in successive binary logistic regression analyses. The remaining 14 items were then subjected to logistic regression with forward selection using the likelihood ratio (22), which resulted in the selection of the final six WIDUS items (Table 2).

Table 2.

WIDUS items and associations with drug use (per hair and/or urine testing) in developmental and validation samples

| B | SE | Wald | p | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental sample (N = 300) | |||||

| 1. I am currently married. | 1.66 | .57 | 8.43 | .004 | 5.23 |

| 2. In the past year I have been bothered by pain in my teeth or mouth. | .92 | .35 | 7.15 | .008 | 2.51 |

| 3. I have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in my entire life. | 1.05 | .40 | 7.02 | .008 | 2.86 |

| 4. Most of my friends smoke cigarettes. | 1.05 | .36 | 8.30 | .004 | 2.86 |

| 5. There have been times in my life, for at least two weeks straight, where I felt like everything was an effort. | .82 | .33 | 6.17 | .013 | 2.27 |

| 6. I get mad easily and feel a need to blow off some steam. | .64 | .36 | 3.25 | .072 | 1.90 |

| Cross-validation sample (N = 100) | |||||

| 1. I am currently married. | .55 | .58 | .90 | .344 | 1.74 |

| 2. In the past year I have been bothered by pain in my teeth or mouth. | -.15 | .53 | .09 | .770 | .86 |

| 3. I have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in my entire life. | 1.28 | .62 | 4.22 | .040 | 3.59 |

| 4. Most of my friends smoke cigarettes. | .27 | .60 | .20 | .654 | 1.31 |

| 5. There have been times in my life, for at least two weeks straight, where I felt like everything was an effort. | .56 | .50 | 1.29 | .256 | 1.76 |

| 6. I get mad easily and feel a need to blow off some steam. | 1.50 | .50 | 9.04 | .003 | 4.46 |

Note. Item 1, “I am currently married,” is reverse scored. Degrees of freedom =1 for all analyses (logistic regression with simultaneous entry of all WIDUS items).

Validity of the 6-item WIDUS

Table 2 also shows the results of a logistic regression in which WIDUS items were entered simultaneously. In the developmental sample, as expected given the item selection process, all WIDUS items showed unique and strong associations with the drug use criterion. In the cross-validation sample, most individual WIDUS items showed the expected drop in item-criterion association. Item six showed a stronger association with drug use in the cross-validation sample, and item two was negatively associated with drug use in the cross-validation sample.

The six WIDUS items were summed to yield a total indirect risk score and subjected to Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis to identify overall concurrent validity. In the developmental sample, the WIDUS yielded an area under the ROC curve (AUROC) of .80 (asymptotic significance < .001). ROC analysis using the developmental sample indicated that a cut score of 3 or higher resulted in optimum discrimination between positive and negative cases. Alternate cut scores of 2 and 4 were also examined in order to evaluate the potential utility of a more sensitive/more specific version, respectively, of this screener.

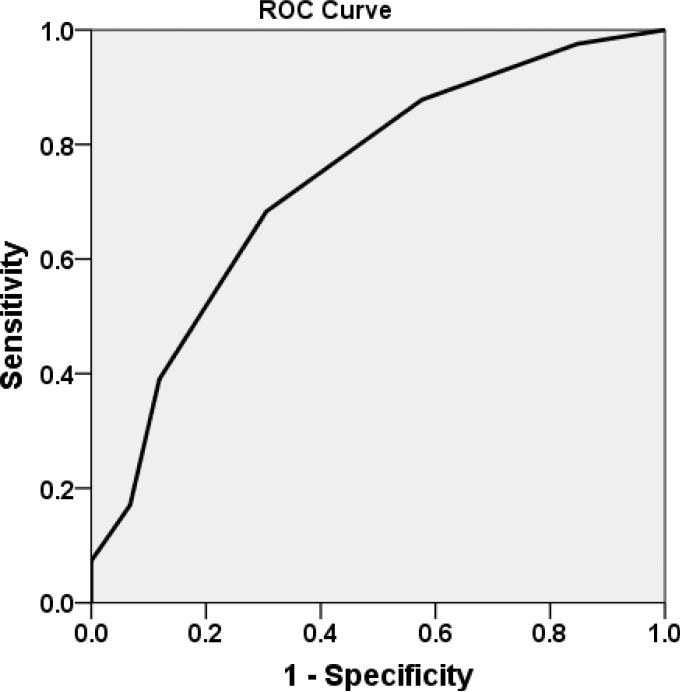

Table 3 shows concurrent validity results in the validation sample. The WIDUS showed better overall correct classification, NPV, and sensitivity than the direct approach. As seen in Figure 1, the WIDUS yielded an AUROC of .74 in the cross-validation sample (asymptotic significance < .001). To directly compare the WIDUS and DAST-10 in terms of classification accuracy, we used bootstrapping to make an AUROC distribution for the WIDUS and the DAST. A total of 60 observations from the validation sample of 100 were resampled with replacement 1,000 times; the Welch two-sample t-test was then applied, yielding a t-value of 51.6, p < .001, suggesting that the AUROC of the WIDUS (.74 in the cross-validation sample) was significantly higher than that of the DAST-10 (.60).

Table 3.

Concurrent validity of the indirect WIDUS screen, semi-indirect, and direct screening items, in the cross-validation sample (N = 100)

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Overall accuracy | NPV rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. WIDUS (cut score 2) | .88 | .42 | .51 | .83 | 61% | 1 |

| 2. WIDUS (cut score 3) | .68 | .69 | .61 | .76 | 69% | 2 |

| 3. WIDUS (cut score 4) | .39 | .88 | .70 | .68 | 68% | 3 |

| 4. DAST-10 (cut score 1) | .37 | .83 | .60 | .65 | 64% | 5 |

| 5. DAST-10 (cut score 2) | .07 | .97 | .60 | .60 | 60% | 6 |

| 6. Self-report of any drug use, 3 months prior to pregnancy | .41 | .83 | .63 | .67 | 66% | 4 |

Note. PPV = Positive Predictive Value; NPV = Negative Predictive Value. NPV rank refers to rank in terms of NPV, with “1” indicating the measure/cut score combination with the best NPV.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the 6-item WIDUS in the cross-validation sample (N = 100, AUC = .74)

The high specificity and low sensitivity of the direct items, together with the high sensitivity and low specificity of the WIDUS, suggested the potential utility of a combined approach. We therefore evaluated an approach in which participants were considered positive if they (a) reported use of drugs in the three months prior to pregnancy, or (b) were WIDUS-positive. As seen in Table 4, overall classification was higher with the combined approach, in both the developmental and cross-validation samples. Using the validation sample, the significance of this increase in accuracy was tested with a hierarchical logistic regression in which the dichotomous WIDUS screening result was entered first, followed by self-report of drug use in the three months prior to pregnancy. The second step in this analysis was significant (χ2 [1] = 11.4, p = .001), indicating that the semi-indirect item predicted additional variance in drug use after controlling for the WIDUS. Notably, the WIDUS also predicted additional variance in drug use when entered second, after first controlling for the semi-indirect item (χ2 [1] = 9.8, p = .002).

Table 4.

Predictive validity of combined approach.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Overall accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined criteria, in developmental sample (N = 300) | .77 | .71 | .43 | .92 | 72% |

| Combined criteria, in validation sample (N = 100) | .76 | .68 | .62 | .80 | 71% |

Note. Using combined criteria, participants were considered to be a positive screen if they were WIDUS positive and/or reported use of any drug at least monthly in the three months prior to pregnancy.

Finally, the linear association of WIDUS scores and proportion of positive drug tests was also examined. There was a strong, linear association between WIDUS scores and the proportion of positive drug tests (Table 5). In both samples, 100% of participants with a score of six on the WIDUS were positive for drug use.

Table 5.

Linear association of WIDUS scores and likelihood of positive toxicology among participants at each score level

| N (%) positive in developmental sample (N = 300) | N (%) positive in cross-validation sample (N = 100) | |

|---|---|---|

| Raw WIDUS score | ||

| 0 | 0 (0%) | 1 (10.0%) |

| 1 | 7 (7.3%) | 4 (20.0%) |

| 2 | 12 (16.2%) | 8 (33.3%) |

| 3 | 15 (28.3%) | 12 (52.2%) |

| 4 | 19 (48.7%) | 9 (75.0%) |

| 5 | 10 (76.9%) | 4 (50%) |

| 6 | 3 (100%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| WIDUS cut score of 3 | ||

| WIDUS neg. ( < 3) | 19 (9.9%) | 13 (24.1%) |

| WIDUS pos. (≥3) | 47 (43.5%) | 28 (60.9%) |

Discussion

Our goal was to develop a screener for illicit drug use in the perinatal period that (a) was validated against toxicological measures rather than self-report, and (b) could sensitively identify women using drugs during the last trimester of pregnancy, regardless of willingness to disclose such use. The urgency of these goals was underscored by two key findings. First, 26.8% of women in this study tested positive for drug use during the last trimester of pregnancy, which in itself is an important finding that echoes results from previous studies (5). Second, 45.2% of participants testing positive for drug use during pregnancy denied any use in the months prior to pregnancy, and 90% of drug-positive participants denied drug use in the three months prior to giving birth. This low rate of disclosure applied even in the context of anonymity and computer-based data collection, both of which have facilitate disclosure (24, 25).

These findings suggest that screening must evolve if it is to capture the majority of at-risk women. In an important but early step in this process, the WIDUS—on cross-validation— demonstrated (a) higher sensitivity and negative predictive value than alternative approaches; (b) better concurrent validity than the direct or semi-indirect approaches; and (c) a strong linear association with the likelihood of drug use. These results suggest that indirect approaches, when rigorously designed, have the potential to identify high proportions of at-risk drug users. The sensitivity and specificity of the WIDUS were lower than is often seen with other screening tools. However, using self-report to predict the results of toxicology tests is more difficult than using self-report of drug use on a brief measure to predict self-report of drug in an interview (a process that, as noted, could simply miss under-reporting in both contexts).

The good performance of the WIDUS in the cross-validation sample was present despite the fact that 1 of the 6 WIDUS items was negatively associated with the criterion in that sample, causing it to reduce rather than enhance validity. This changing of signs could be due to sampling error or to a suppression effect (26). Future research should examine the impact of removing this item.

The strong performance of the semi-indirect item was also notable. Asking participants about drug use in the months prior to pregnancy yielded good overall classification accuracy. The low sensitivity and high specificity of the semi-indirect approach, together with the less specific but more sensitive WIDUS, allowed the two approaches to combine successfully: sensitivity increased from .68 to .76, and the addition of either measure yielded a significant improvement in classification over the other. The combined approach shows promise, either via concurrent screening (including semi-indirect and WIDUS items in a single measure) or sequential (administering the WIDUS if drug use is denied). However, the modest gains in classification accuracy using this approach must be weighed against the possible impact of asking about drug use specifically. For example, a screener without any stigmatizing items of any kind may be administered and completed at a higher rate.

Clearly, the utility of indirect approaches will vary with setting. For example, in contexts in which disclosure of drug use is normative and/or safe, direct approaches such as the DAST-10 are likely to perform better than in settings where the potential for negative consequences is high. Whether or not the WIDUS would perform differently in a context in which the risks of disclosure were lower is unclear, and an important topic for future research.

Limitations

Several limitations must be noted. First, although cross-validation in a new sample provides some support for the WIDUS, the validation sample was drawn from the same relatively homogenous population using similar methods. Generalizability is thus limited. Given the investigational nature of our approach, the sample chosen was quite intentional: it allowed us to first test whether such a screener has potential utility in a homogeneous sample with a high base rate of drug use. However, as noted, it is essential that the WIDUS be subjected to future cross-validation efforts, with a range of samples, before being considered for widespread use. Future efforts can examine whether some items might predict well across samples or whether entirely different versions might be necessary. Second, the cross-validation sample was significantly more likely than the developmental sample to test positive for drug use. This unexpected difference may have increased the inevitable falloff in validity on cross-validation. Third, there is evidence that the order in which items are administered, and the nature of other items in a measure, have clear effects on item and measure characteristics (27). The WIDUS has not yet been evaluated as a discrete 6-item measure. Fourth, using objective evidence of drug use during pregnancy as a gold standard is a significant strength of this study, particularly since drug use during pregnancy is more likely to reflect problem use than evidence of use outside of pregnancy. Nevertheless, this criterion is not the same as identifying problem-level use.

Conclusions

This analysis evaluated the a rigorously developed indirect screener for drug use in the perinatal period. Findings support previous evidence that under-reporting of drug use is substantial in some contexts. Findings also suggest that indirect methods can facilitate identification of at-risk women. Although none of the measures evaluated in this study resulted in highly accurate identification of women using drugs during pregnancy, the six-item WIDUS with a cut score of either 3 or 4 identified drug use more accurately than the alternative approaches, and the WIDUS with a cut score of 2 was far more sensitive than other screeners. Although a cut score of 3 appeared to result in the best overall classification, different cut scores can be used to maximize either sensitivity or specificity, depending on priorities and the relative cost of a false positive or false negative.

Should indirect screening continue to show promise, it would require evolution in brief intervention approaches. Clearly, persons denying drug use but meeting criteria on an indirect screener should not be confronted with “evidence” of their use, an approach that would be inaccurate, unethical, and counterproductive. Brief interventions that address substance use in a non-specific way, in the context of several other potential health risks, may be helpful; indirect screeners such as the WIDUS could be embedded within broader screening efforts regarding other health-related behaviors such as diet, exercise, and alcohol use, and introduced as a general effort to promote health. Future research should evaluate whether it is possible for a brief intervention to reduce drug use without directly presuming the presence of that behavior.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA018975).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest declaration: None.

Contributor Information

Steven J. Ondersma, Wayne State University.

Dace S. Svikis, Virginia Commonwealth University

James M. LeBreton, Purdue University

David L. Streiner, University of Toronto

Emily R. Grekin, Wayne State University

Phebe K. Lam, Wayne State University

Veronica Connors-Burge, Wayne State University.

References

- 1.Magura S, Kang SY. Validity of self-reported drug use in high risk populations: a meta-analytical review. Subst Use Misuse. 1996 Jul;31(9):1131–53. doi: 10.3109/10826089609063969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colon HM, Robles RR, Sahai H. The validity of drug use responses in a household survey in Puerto Rico: comparison of survey responses of cocaine and heroin use with hair tests. Int J Epidemiol. 2001 Oct;30(5):1042–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.5.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kline J, Ng SK, Schittini M, Levin B, Susser M. Cocaine use during pregnancy: sensitive detection by hair assay. Am J Public Health. 1997 Mar;87(3):352–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.3.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markovic N, Ness RB, Cefilli D, Grisso JA, Stahmer S, Shaw LM. Substance use measures among women in early pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Sep;183(3):627–32. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostrea EM, Jr., Brady M, Gause S, Raymundo AL, Stevens M. Drug screening of newborns by meconium analysis: a large-scale, prospective, epidemiologic study. Pediatrics. 1992 Jan;89(1):107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bessa MA, Mitsuhiro SS, Chalem E, Barros MM, Guinsburg R, Laranjeira R. Underreporting of use of cocaine and marijuana during the third trimester of gestation among pregnant adolescents. Addict Behav. 2010 Mar;35(3):266–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokotailo PK, Langhough RE, Cox NS, Davidson SR, Fleming MF. Cigarette, alcohol and other drug use among small city pregnant adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1994 Jul;15(5):366–73. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(94)90259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yudko E, Lozhkina O, Fouts A. A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007 Mar;32(2):189–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM, Gleason JR. Use of the AUDIT and the DAST-10 to identify alcohol and drug use disorders among adults with a severe and persistent mental illness. Psychol Assess. 2000;12(2):186–92. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7(4):363–71. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grekin ER, Svikis DS, Lam P, Connors V, Lebreton JM, Streiner DL, et al. Drug use during pregnancy: validating the Drug Abuse Screening Test against physiological measures. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010 Dec;24(4):719–23. doi: 10.1037/a0021741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richter KP, Kaur H, Resnicow K, Nazir N, Mosier MC, Ahluwalia JS. Cigarette smoking among marijuana users in the United States. Subst Abus. 2004 Jun;25(2):35–43. doi: 10.1300/j465v25n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenblum A, Joseph H, Fong C, Kipnis S, Cleland C, Portenoy RK. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain among chemically dependent patients in methadone maintenance and residential treatment facilities. JAMA. 2003 May 14;289(18):2370–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg JF, Singer TM, Garno JL. Suicidality and substance abuse in affective disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 25):35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-45862010; Rockville, MD: [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson RF, Self-Brown S, Fricker-Elhai AE, Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE, Resnick HS. The relations between family environment and violence exposure among youth: findings from the national survey of adolescents. Child Maltreat. 2006 Feb;11(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/1077559505279295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, Cornelius JR, Pajer K, Vanyukov M, et al. Neurobehavioral disinhibition in childhood predicts early age at onset of substance use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 Jun;160(6):1078–85. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. Validity of the drug abuse screening test (DAST-10) in inpatient substance abusers: Problems of drug dependence.. NIDA Research Monograph Series: Procedings of the 53rd Annual Scientific Meeting, The Committee on Problems of Drug Dependence 1991;DHHS Publication No. 92-1888; Department of Health and Human Services. Rockville, MD. p. 233. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humeniuk R, Ali R. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) and pilot brief intervention: A technical report of phase II findings of the WHO ASSIST Project: World Health Organization. 2006 Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/assist/en/index.html.

- 20.Newcombe DA, Humeniuk RE, Ali R. Validation of the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): report of results from the Australian site. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005 May;24(3):217–26. doi: 10.1080/09595230500170266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowe JB, Windsor RA, Adams B, Morris J, Reese Y. Use of a bogus pipeline method to increase accuracy of self-reported alcohol consumption among pregnant women. J Stud Alcohol. 1986 Mar;47(2):173–5. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1986.47.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X, Jin Z. Item reduction in a scale for screening. Stat Med. 2007 Oct 15;26(23):4311–27. doi: 10.1002/sim.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Streiner DL. Being inconsistent about consistency: When coefficient alpha does and doesn't matter. J Pers Assess. 2003;80(3):217–22. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA8003_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newman JC, Des Jarlais DC, Turner CF, Gribble J, Cooley P, Paone D. The differential effects of face-to-face and computer interview modes. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(2):294–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Durant LE, Carey MP, Schroder KE. Effects of anonymity, gender, and erotophilia on the quality of data obtained from self-reports of socially sensitive behaviors. J Behav Med. 2002 Oct;25(5):438–67. doi: 10.1023/a:1020419023766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinberger AH, Darkes J, Del Boca FK, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Items as context: Effects of item order and ambiguity on factor structure. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2006;28(1):17–26. [Google Scholar]