Abstract

Genome-wide association studies have seen unprecedented success in identifying genetic loci that correlate with disease susceptibility and severity. Early phases of these studies have predominantly been performed in the Caucasian populations. The next phase in medical genetics is to extend the exploration across genetically diverse populations to leverage on larger sample sizes for locating smaller effects that may be present in most human populations. However, discoveries from these studies do not actually reveal the underlying functional changes to the human genome, but only point to broad regions stipulated by the extent of linkage disequilibrium (LD). Fine-mapping the functional variants can, however, be hampered by extensive LD, which can yield multiple perfect surrogates that are not distinguishable from the underlying causal variants, although several studies have illustrated the value of relying on multiple genetically diverse populations to narrow the candidate regions where the functional variants can be found in. Here, we explore the efficiency of trans-ethnic meta-analysis in discovering genetic association and in fine-mapping the causal variants by asking: are there any population diversity metrics that will be useful for: (i) identifying the populations or genomic regions where meta-analysis are likely to be more successful for discovering associations?; (ii) identifying the populations or loci to perform deep targeted sequencing for the purpose of fine-mapping causal variants? Our results indicate that simple metrics like the FST or the population specificity of haplotypes are useful in trans-ethnic meta-analyses, while the degree of haplotype sharing and LD variation are informative of the efficiency in trans-ethnic fine-mapping.

Keywords: linkage disequilibrium, genome-wide association study, meta-analysis, fine-mapping

Introduction

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been successful at identifying genetic loci that correlate with disease susceptibility and severity.1, 2 Early phases of GWAS and genome-wide meta-analyses (GWMA) have predominantly been performed in the Caucasian populations, although increasingly there are reports of GWAS and GWMA involving non-Caucasian communities from Africa,3, 4 East and South Asia,5, 6, 7 and admixed African-Americans.8, 9 These have validated many previous discoveries made in the Caucasian populations, as well as identified and even guided the discovery of previously unsuspected loci that are either likely to be ancestry specific or are present at higher frequencies in the non-Caucasian populations. The KCNQ1 association with Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a classic example where the initial discovery was made in East Asians and subsequently validated in Caucasians, as the risk alleles of the associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were at higher frequencies in East Asian populations than in Europeans.10, 11 The next phase in genome-wide studies will be to meta-analyze as many of the available GWAS as possible, to increase sample sizes for locating the smaller effects that will be generally present in most human populations, as well as to leverage on the differential allele frequency spectrum to identify loci like KCNQ1. However, this means such meta-analyses will take place across genetically diverse populations, which presents additional challenges owing to the use of tagging SNPs in GWAS.12, 13

Although the extent of the phenotypic variance that has been accounted for by discoveries made from these studies remained moderate at best,14 the belief is that identifying the causative variants will increase the heritability estimates, as has recently been shown in the fine-mapping of known loci for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, which effectively doubled the variance estimates.15 However, fine-mapping causal variants suffer from the conundrum of long-range linkage disequilibrium (LD), where a stretch of high LD means there may be several neighboring markers that are indistinguishable from the unknown functional polymorphism simply on the basis of the strength of phenotypic association.13, 16 Integrating data from multiple diverse populations has been shown to increase the efficiency of fine-mapping by leveraging on the differential patterns of LD, identifying SNPs that are consistent with the observed association signals in the separate populations.16

Given that both the primary goal of discovering genotype–phenotype associations and the secondary aim of localizing the functional variants are converging on meta-analyzing multiple genetically diverse populations, the natural question will be whether there are particular combinations of populations that increase the efficiency of the trans-ethnic meta-analyses. For example, are there any population diversity metrics that will be informative for: (i) identifying the populations or genomic regions where meta-analysis is likely to be more successful, or conversely to provide possible insight into a failure to reproduce known associations in populations of different ancestries; (ii) identifying the populations or loci to perform trans-ethnic fine-mapping, given that such experiments typically require costly deep targeted sequencing of either a reference population or of a small set of cases and controls.

The FST is the most commonly utilized metric to assess population diversity. At the single-SNP level, the FST measures inter-population variation in the frequency of an allele; whereas at the population level, the genome-wide FST provides a numerical quantification of genetic distance between populations. These applications of the FST metric fundamentally query each SNP individually and may not provide an indication of the localized genomic variation between populations. In interrogating the human genome for phenotypic associations, functional variants may have arose as a consequence of selective adaptation to hostile environments due to climate, diet and pathogens, and this may produce localized genetic differences between populations that may not be adequately represented with genome-wide metrics of population diversity.17

Here, we perform an investigation into the correlation between different population diversity metrics with the efficiency of trans-ethnic meta-analyses for the dual purposes of discovering associations and fine-mapping causal variants. We evaluate four population diversity metrics that rely on comparing one of the following using SNPs that are found in the vicinity of a simulated causal variant: (i) the variation in the allele frequencies at each SNP across the populations (regional FST); (ii) the degree of haplotype similarity in the genomic region across the populations (haplotype entropy and haplotype similarity); and (iii) the differential patterns of LD between the populations (varLD). We subsequently apply these metrics to consider 43 established loci for T2D, and investigate which of these loci are likely to benefit the most from trans-ethnic analyses.

Materials and methods

Data sets

To simulate case–control data, the phased haplotypes for 988 individuals in the 11 populations in Phase 3 of the International HapMap Project 18 were used as seed data. This consists of 1 387 394 SNPs that are found on either the Affymetrix 6.0 or the Illumina 1M genotyping microarrays and are present in all 11 populations. The population-averaged recombination rates from Phase 2 of the HapMap19 were also used to perform the simulations.

Case–control simulation

We simulated case–control data for each of the 11 populations with the HAPGEN20 program using seed haplotypes from the corresponding HapMap 3 population, with effective population sizes of 11418 for populations of Caucasian and South Asian ancestries (CEU, GIH, MEX and TSI); 14 269 for East Asian populations (CHB, CHD and JPT); and 17 469 for populations with African ancestries (ASW, LWK, MKK and YRI). To generate genotype data for samples with a dichotomous phenotype outcome, we identify the set of SNPs that are not present on the Illumina 1M BeadChip (thus effectively the SNPs that are found on the Affymetrix 6.0 array only) and are polymorphic in all 11 populations as the set of possible causal variants. Each candidate causal variant is categorized according to the minor allele frequency (MAF) in CEU into three MAF bins: (i) high frequency defined as 0.2≤MAF≤0.5; (ii) medium frequency, 0.05≤MAF<0.2; and (iii) low frequency, 0.01≤MAF<0.05. To assess the impact of long-range LD in fine-mapping the causal variants, we deliberately selected causal variants that are in perfect LD (defined as r2=1) with more than five other SNPs located within 100 kb of the candidate SNP in the CEU panel. For each of the three MAF bins, we identified 1000 candidate causal variants across the autosomal chromosomes, and generated 4000 cases and 4000 controls in each population at each causal variant by assuming a multiplicative disease effect with an allelic relative risk of 1.2.

Association and meta-analysis

The case–control association analysis is performed using the SNPTEST program (version v1.1.5, https://mathgen.stats.ox.ac.uk/genetics_software/snptest/snptest.html) with the frequentist additive test of association, which is equivalent to a logistic regression. The meta-analysis across multiple populations uses the standard fixed effects meta-analytic approach, which pools the logarithm of the odds ratios while weighting the contribution for each population by the inverse of the square of the standard errors. These analyses are performed in two scenarios: (A) the ‘Association' scenario where we mimic the conditions of an actual GWAS by thinning the SNP density to only the content present on the Illumina 1M array (which will thus not include the causal variant); (B) the ‘Fine-map' scenario where we use all the simulated SNPs (including the causal variant). In scenario (A), we are interested in measuring the strength of the largest association signal in each region, as well as the change in the association signals upon meta-analysis. In scenario (B), the outcome of interest is in the rank of the association signal at the causal variant relative to all other SNPs in the region. The meta-analyses are performed across two, three and four populations, by considering configurations where the populations are minimally differentiated (for example, in three population analysis, between CHB, CHD and JPT) to maximally differentiated (for example, between CEU, CHB and YRI).

Population diversity metrics

To assess the genome-wide diversity between populations, we first perform a principal component analysis (PCA) using the pca command in the eigenstrat program 21 across 60 466 SNPs that are present in all 11 populations. The SNPs are identified by choosing the first SNP out of every 20 consecutive SNPs. Second, we calculated the genome-wide FST by taking the average of the autosomal SNP-level FST, which for each SNP is calculated as the proportion of variance in allele frequencies of a SNP between the populations. To quantify the degree of genomic diversity around each causal variant between the different population configurations, we implemented the following four metrics for SNPs found within 50 kb on either flanks of the causal variant.

Regional FST

The regional FST is quantified as the average of the SNP-level FST for SNPs within 50 kb of either flanks of the causal variant. This metric is bounded between 0 and 1, with larger values indicating that there is greater variation in the allele frequencies for SNPs located in the region.

Haplotype entropy

Within the 100-kb region when considering K populations, the set of unique haplotypes that are present with frequencies of at least 2% in each population is collated across all K populations, defined as {h1, h2, …, hL}. The frequency of each of these haplotypes in the set is tabulated across each of the K populations to yield population-specific frequencies, defined as fij for haplotype hi in the jth population. The conditional probability for each population given haplotype hi, Fij, can be calculated as fij/(Σjfij). We can calculate the relative mutual information for haplotype hi as RMI(hi)=1+Σj(Fij log Fij)/log(K). The haplotype entropy for the genomic region is thus the overall frequency weighted sum of the individual relative mutual information estimates, or Σi[(Σifi•) RMI(hi)]/(Σifi•), where fi• represent the frequency of haplotype hi calculated across all K populations. This metric is intuitively a measure of population specificity of haplotypes and is bounded between 0 and 1, with larger values indicating there are specific haplotypes that are more common in some populations than others and thus reflective of greater haplotype diversity across the populations.

Haplotype similarity

Within the 100-kb region when considering K populations, the set of unique haplotypes that are present in all K populations are identified. The haplotype similarity is defined as the proportion of the haplotypes across the K populations that have been represented by these haplotypes. This metric is bounded between 0 and 1, with larger values indicating greater degrees of haplotype sharing between populations and thus reflects lower haplotype diversity across the populations.

varLD

As varLD is a metric for quantifying LD variation between two populations,22 we perform the varLD calculation across every possible pair of the 11 populations in HapMap 3. Briefly, we consider windows of 50 consecutive SNPs and calculate the signed r2 for every possible SNP pair 23 within each of the two populations. An eigen decomposition can be applied to the resulting 50 × 50 signed r2 correlation matrix for the 50 SNPs, and the evidence for LD variation between the two populations is measured by the sum of the absolute difference between the ranked eigen values from the two eigen decompositions. The genome-wide distribution of this metric is subsequently standardized to yield a mean of 0 and a s.d. of 1. For each causal variant, we consider the standardized varLD statistic for the window with center closest to the location of the causal variant. When the meta-analysis is performed across more than two populations, we quantify the composite varLD score as the average of the varLD statistics from all possible pairs of populations. This metric is centered at 0, where larger negative values correspond to lower inter-population LD variation and larger positive values are indicative of greater LD differences between populations.

Application to T2D loci

We consider the 43 loci in autosomal chromosomes that have consistently been associated with T2D in Caucasians24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 as of September 2011 (see Supplementary Table 1 for the listing of the loci). For each of these loci, the index or proxy SNP is identified, and we consider all the SNPs present in the HapMap 3 database located within 50 kb on either flanks of the focal position. These SNPs are subsequently used to calculate the four localized population diversity metrics.

Results

We briefly reviewed the population structure across the 11 populations from Phase 3 of HapMap by calculating the genome-wide FST and by performing PCA. We observed that the greatest genetic diversity is seen between East Asian populations (CHB, CHD and JPT) and African populations (ASW, LWK, MKK and YRI), and the next largest source of genetic diversity stems from comparing the European, Hispanic and South Asian populations to the Africans and East Asians (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). As both PCA and the genome-wide FST are calculated with autosomal SNPs across the genome, these analyses measure overall genetic diversity between populations, but they may not be representative of local variations in the genome.

In our assessment on efficiency of genetic meta-analysis for the purposes of (i) discovering associations; and (ii) identifying the causal variants underlying associations identified from GWAS, we have combined between 2 and 4 of the 11 populations in HapMap 3 in different configurations to investigate the relationship between the different population diversity metrics and the outcome of the meta-analysis. For example, we considered a population configuration consisting of three East Asian populations (CHB, CHD and JPT) that has the least genetic diversity as measured by genome-wide FST (0.7%), whereas the three-population configuration of CEU, CHB and YRI produces a combination with considerably larger FST (9.7%).

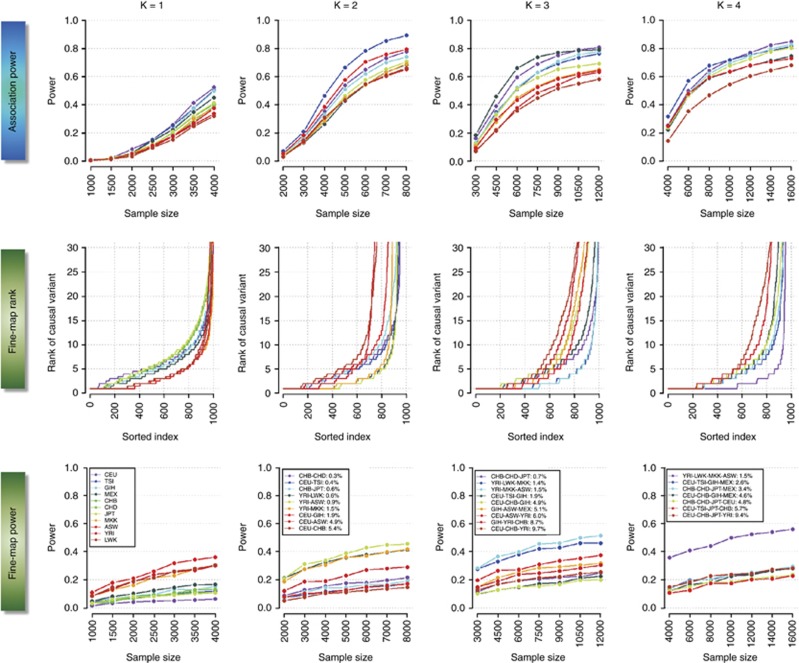

There are different measures of outcome for the two purposes in our study. In the first scenario of discovering associations, the outcome is defined as the ability to successfully identify an association signal stronger than genome-wide significance, or a P<5 × 10−8. Naturally as the sample size of the study or meta-analysis increases, the power to identify a genuine association increases (top panel of Figure 1). In the second scenario of fine-mapping the causal variants, the outcome is defined as whether each simulated causal variant successfully attains the top rank when the association signals of all the SNPs in the region in the study or meta-analysis are ranked from most significant (smallest P-value) to least significant (middle and bottom panels of Figure 1). It is similarly evident that the ability to identify the causal variant increases as sample size increases.

Figure 1.

Overall performance of trans-ethnic meta-analysis and fine-mapping. The panels in the top row quantifies the power to identify an association in a single population (K=1, first column), and in meta-analyses across either two, three or four populations (second, third and fourth column, respectively), at different sample sizes. The middle row represents the ranking of the association signal at each causal variant across all 1000 iterations when considering a sample size of 4000 cases and 4000 controls within each population. The lowest attained value on the vertical axis is 1, which indicates that the causal variant is correctly identified as the SNP displaying the strongest association signal. The horizontal axis represents the 1000 iterations of the simulation. The bottom row represents the power of identifying the causal variant as the SNP with the strongest association signal at different sample sizes. The color of each line for three panels in each column corresponds to a specific population configuration, which is summarized in the legends in the bottom panels along with the FST values estimated across all the autosomal SNPs in the genome. For K=2, 3 and 4, the colors of the lines are assigned according to the FST such that population configurations with increasing FST are assigned warmer colors (from blue to red). Each causal variant is chosen to possess a MAF of between 20 and 50%, and to be in perfect LD with at least five other neighboring markers in the CEU panel.

Genome-wide population diversity

When there is only one population (K=1, Figure 1), our simulations suggested that European populations enjoy the highest power for discovering associations when MAF>0.2, than East Asian and African populations. However, this is an artifact introduced by the way we have selected the causal variants, using the allele frequencies and LD patterns from CEU (Supplementary Figure 3 for simulations with YRI-defined causal variants, and Supplementary Figures 4 and 5 for SNPs with MAFs<20%). However, the correspondence between genome-wide FST and the ability of the meta-analysis to discover association signals is consistent regardless of how the causal variants have been defined, and population configurations with higher FST consistently yield lower power to discover associations (for K=2, 3 and 4, Figure 1).

The correspondence between genome-wide FST and the ability to fine-map the causal variant with trans-ethnic meta-analyses is less apparent though (Figure 1). Regardless of which population the causal variants were defined with, analyses involving African populations tend to yield the greatest ability to identify the causal variant as the SNP with the strongest association signal. This is true whether we are considering just one African population or a meta-analysis of four African populations, suggesting that genome-wide FST is not immediately indicative of the efficiency of trans-ethnic fine-mapping.

Localized population diversity

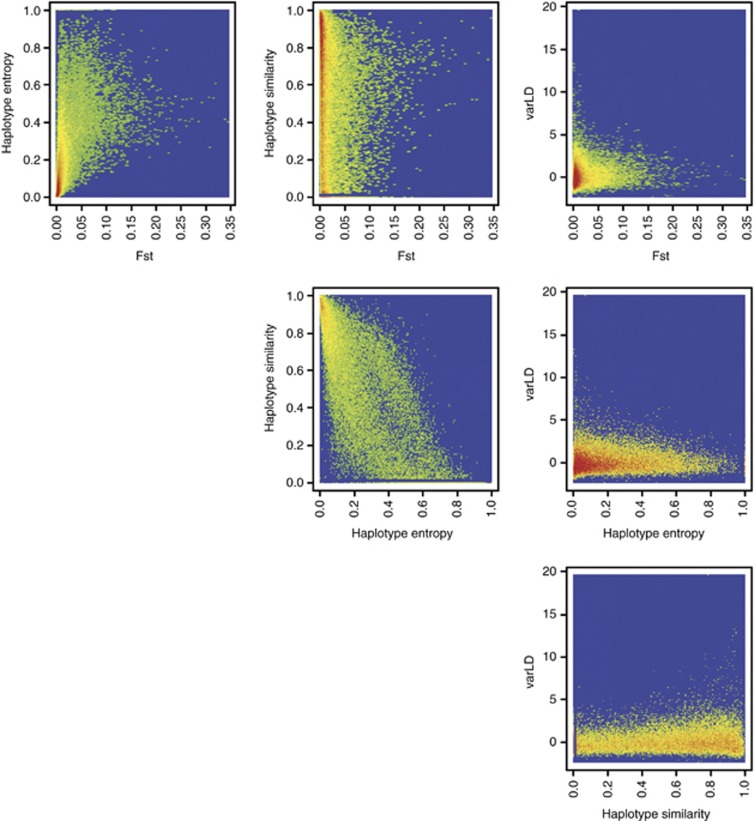

We extend our analysis to consider four localized population diversity metrics that are calculated in the 100-kb region around the causal variant (50 kb on either flanks of the causal variant): (i) regional FST, which summarizes the SNP-level FST across the region; (ii) haplotype entropy, a scaled metric between 0 and 1 that effectively compares the haplotype frequencies of the dominant haplotype forms between the populations; (iii) haplotype similarity, which quantifies the extent of similarity in the haplotypes from the different populations; and (iv) composite varLD, which measures the extent of LD differences between the populations. Across all three sets of 1000 simulations, other than between haplotype similarity and haplotype entropy where the two metrics appear to be negatively correlated, there is no striking relationship between the remaining pairings of the four metrics (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relationship between the four localized population diversity metrics. Each of the six panels illustrates the relationship between two population diversity metrics calculated from the population configurations used in the meta-analyses of two, three and four populations. Each figure is plotted in a density style where warmer colors indicate a greater concentration of data points while cooler colors represent sparser density, with blue as the background color of 0 density.

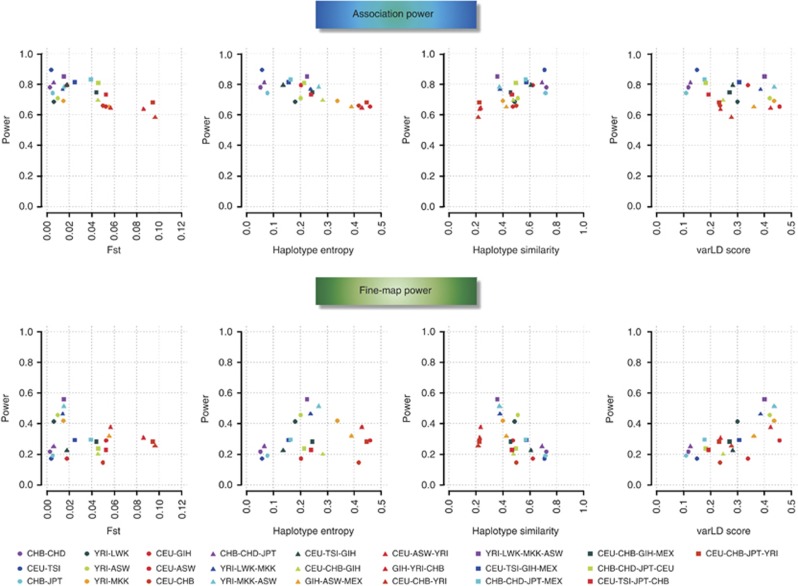

We first interrogated the summary of each of the four localized metrics obtained from the meta-analyses of two to four populations, by calculating the average of each localized metric across all the simulated causal variants within each population configuration (Figure 3, Supplementary Figures 6–8). We observe there exists a significant negative correlation between the average regional FST values across all the simulated causal variants and the power to discover associations in meta-analyses (Pearson's correlation ρ=−0.67, P=2.7 × 10−4). A stronger negative association is seen for haplotype entropy (ρ=−0.83, P=3.0 × 10−7) while haplotype similarity is positively correlated with statistical power (ρ=0.64, P=6.0 × 10−4). There is, however, no association between the composite varLD score and power (P=0.151). Conversely, the power to fine-map the causal variant is not associated with the regional FST metric (P=0.361) or the haplotype entropy (P=0.591). Although the haplotype similarity is moderately associated with fine-mapping power (ρ=−0.47, P=0.017), the composite varLD score was more correlated with the power of trans-ethnic fine-mapping (ρ=0.70, P=8.7 × 10−5). Although the extent of these findings varied with the MAFs of the causal variants, the overall trends in the relationships were consistent throughout. These results suggest the localized metrics that are indicative of fine-mapping efficiency (composite varLD, haplotype similarity) are actually different from the metrics that are informative for association discovery (regional FST, haplotype entropy).

Figure 3.

Comparison of power with population diversity metrics. The panels in the top row show the power to identify an association when meta-analyzing different populations against four metrics of population diversity (regional FST, haplotype entropy, haplotype similarity and composite varLD). The panels in the bottom row are plotted against the same four metrics of population diversity, except the vertical axis measures the power of identifying the causal variant as the SNP with the strongest association signal. Results from the meta-analyses of two, three and four populations are represented with circles, triangles and squares, respectively, while the colors within each category are assigned according to the genome-wide FST between the corresponding populations, such that configurations with increasing FST are assigned warmer colors. This figure shows the findings for causal SNPs with MAFs between 20 and 50% in CEU.

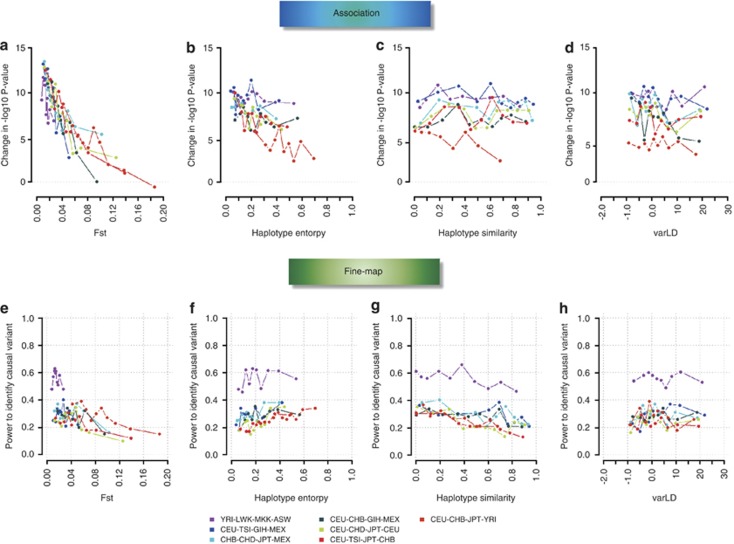

We additionally considered the performance of the localized metrics when meta-analyzing four populations (K=4) as well as the relationships of these metrics with the efficiency of meta-analysis (Figure 4, Supplementary Figures 9 and 10). We identify the 100 simulated causal variants (out of 1000) that fall within the appropriate decile of each metric, and calculated: (i) the difference between the –log10P-values from the meta-analysis and the most significant single-population analysis, which thus represents how much stronger the meta-analysis P-value was compared with the individual studies; (ii) how many of these 100 causal variants attained the strongest association evidence in the simulated region, which we quantified as the empirical power to identify the causal variant. We observed that the regional FST and haplotype entropy exhibited a very strong negative relation with the change in –log10P-value for discovering associations, where low FST and haplotype entropy values can result in 10-fold increases (Figures 4a and b). However, there was no apparent trend between the change in statistical evidence with either haplotype similarity or varLD score (Figures 4c and d). Intriguingly, when we considered deciles, we observed that there is a moderate trend between regional FST and haplotype entropy with the power to identify the causal variant: increasing FST actually appear to correspond with decreasing power (Figure 4e), while meta-analyses with populations with larger haplotype entropy values yielded higher power (Figure 4f). Consistent with previous observations, increasing degree of haplotype similarity actually decreases the ability to identify the causal variant (Figure 4g), while there was no apparent correlation between varLD and the power to fine-map the causal variant (Figure 4h).

Figure 4.

SNP-level comparison of meta-analysis efficiency against population diversity metrics. The panels illustrate the efficiency of performing meta-analyses across four populations for the different population diversity metrics. The efficiency of the meta-analysis for identifying association is quantified as the difference in the –log10P-values of the meta-analysis from the most significant single-population analysis (a–d), whereas the efficiency for fine-mapping is quantified as the ability to identify the causal variant as the SNP exhibiting the strongest association signal (e–h). Across the 1000 simulated causal variants, the deciles for each population metric are identified, and the averages of the efficiency metrics are calculated for the 100 SNPs falling within each decile. This figure shows the findings for causal SNPs with MAFs between 20 and 50% in CEU.

Application to T2D loci

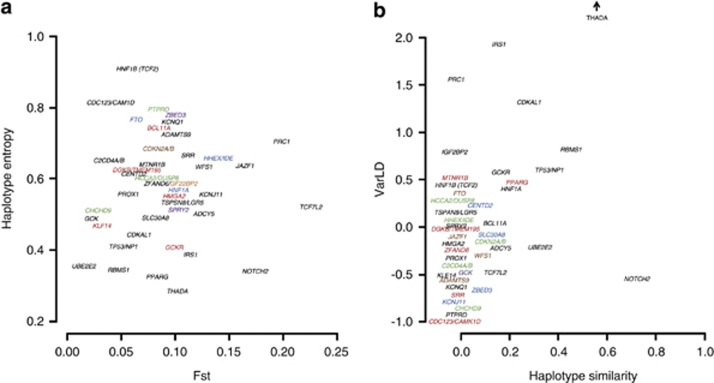

For each of the 43 known T2D loci that are identified from GWAS or meta-analyses of European populations (Supplementary Table 1), we calculated the values of the four metrics for the 100-kb region flanking the known index SNP across the four main HapMap 2 populations of CEU, CHB, JPT and YRI (Figure 5). We observe that loci like TCF7L2, PRC1 and JAZF1 exhibit both high regional FST and haplotype entropy (Figure 5a), which coincide with reports that the associations at these loci tend to be found in certain populations (South Asians)32 but not others (East Asians, South-East Asian Malays).7 Conversely, the other spectrum of low regional FST and haplotype entropy included loci like CDKAL1, SLC30A8 and IRS1 where the associations are consistently reproduced across East and South Asians.5, 7 For a higher chance of success in identifying the causal variants, adopting a trans-ethnic approach to T2D loci like THADA, IRS1, PRC1 and CDKAL1 may be useful as they are found in genomic regions with either a lower degree of haplotype similarity or a higher extent of LD variation between populations (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Population diversity at 43 T2D loci. The panels illustrate the genetic diversity across CEU, CHB, JPT and YRI at the 43 validated T2D loci. For each of these loci, SNPs found within the 100-kb region flanking the known index SNP are used to tabulate four population diversity metrics, where: (a) shows haplotype entropy against regional FST – two metrics shown to be informative for assessing meta-analysis efficiency such that larger values of either metric correlate with lower power for finding associations in meta-analyses; (b) shows varLD against haplotype similarity – two metrics shown to be informative for assessing the efficiency of trans-ethnic fine-mapping such that higher varLD scores and lower haplotype similarity correlate with higher power for locating the causal variant at each locus as the SNP with the strongest association evidence. The composite varLD score for THADA is 3.2, and we have represented this locus in a truncated manner to maximize the plot area for the rest of the genes. Gene names of some of the loci have been shown in different colors for purely esthetic reasons to differentiate between loci with similar metric values.

Discussion

We set out to investigate whether there are any population diversity metrics that will be useful for identifying the populations or genomic regions where trans-ethnic approaches to meta-analyses and fine-mapping are likely to be more efficient. By simulating case–control data with genetic ancestries that are representative of the 11 populations in Phase 3 of the HapMap project, we have explored the correlation between the efficiency of meta-analysis with four metrics that assess different features of trans-population genetic diversity. These looked at: (i) variations in allele or haplotype frequencies; (ii) the degree of haplotype similarity; and (iii) the extent of LD variation between populations involved in the meta-analyses of SNPs in the genomic region that flanks a simulated causal variant shared across all 11 populations. Our results consistently suggest that quantifying the average FST of the SNPs in the region or measuring the population specificity of haplotypes in the region is indicative of meta-analysis efficiency at the preliminary stage of discovering genotype–phenotype association. However, at the secondary stage of fine-mapping the causal variants, these metrics appear to be less informative of trans-ethnic fine-mapping efficiency. Instead, assessing the degree of haplotype sharing and the extent of LD variation between populations are more informative for predicting the efficiency of trans-ethnic fine-mapping.

Metrics like regional FST and haplotype entropy effectively assess the degree of similarity in the frequencies of the associated alleles at the SNPs in the region across the different populations. It is perhaps not surprising that these frequency-based metrics are more predictive of meta-analysis efficiency in association discovery, as a region with low regional FST or haplotype entropy likely indicates: (i) the functional allele has a similar frequency across the different population; (ii) the mutation event introducing the functional allele is likely to predate the most common recent ancestor for these populations; and/or (iii) the functional allele is likely to sit on a common haplotype that is shared across the populations. On the other hand, metrics like haplotype similarity and varLD interrogates higher-order information with regard to the diversity of haplotypes that are present in the region, particularly in the case of varLD that interrogates the correlation patterns between every pair of SNPs. These latter metrics are particularly valuable in addressing the efficiency of trans-ethnic fine-mapping, as they assess whether the functional allele is likely to reside on different haplotypes in the different populations, which can circumvent the predicament of long-range LD.

Although it seems that our interpretations of these metrics suggest they are fundamentally similar or even surrogates to haplotype sharing, we emphasize the difference between the following two statements: (A) the functional allele sits on a shared haplotype; (B) the functional allele sits on different haplotypes that are shared across different populations. In scenario A, there is one dominant haplotype that carries the functional allele and this haplotype predominates in most populations (and is quantified by the haplotype entropy metric); in scenario B, there are multiple haplotype forms that carry the functional allele, and whether these different forms are similarly present in most of the populations is what the haplotype similarity metric is trying to quantify. In terms of the nature of LD between the SNPs, scenario A corresponds to the situation where SNPs in the region possess high r2 across the different populations whereas scenario B corresponds to the situation where SNPs in the region can possess differential r2 across the different populations.

The discovery that different population genetic metrics are more appropriate for investigating meta-analysis efficiency in discovering associations and fine-mapping is timely, as different disease consortiums are starting to congregate to perform global GWMA to leverage on larger sample sizes for association discoveries, and also to identify the confirmed associations to take to the fine-mapping stage. It is inevitable there will be situations where an association identified in a collection of populations does not successfully reproduce in other global populations, and these metrics now provide the means of quantifying whether the failure to replicate is likely to be a consequence of significant genetic diversity at the local region surrounding the association. Similarly, the application of haplotype similarity and varLD metrics will be valuable for prioritizing loci to take forward for trans-ethnic fine-mapping, especially as this is expected to require costly targeted sequencing experiments, whether for the purpose of generating a population-specific imputation reference panel or to perform actual targeted sequencing of cases and controls.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Inga Prokopenko for sharing the list of the 43 T2D loci. This project acknowledges the support of the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health from the National University of Singapore and the National Research Foundation Singapore (NRF-RF-2010-05).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Donnelly P. Progress and challenges in genome-wide association studies in humans. Nature. 2008;456:728–731. doi: 10.1038/nature07631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MI, Hirschhorn JN. Genome-wide association studies: past, present and future. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:R100–R101. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallow M, Teo YY, Small KS, et al. Genome-wide and fine-resolution association analysis of malaria in West Africa. Nat Genet. 2009;41:657–665. doi: 10.1038/ng.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thye T, Vannberg FO, Wong SH, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identifies a susceptibility locus for tuberculosis on chromosome 18q11.2. Nat Genet. 2010;42:739–741. doi: 10.1038/ng.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooner JS, Saleheen D, Sim X, et al. Genome-wide association study in individuals of South Asian ancestry identifies six new type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2011;43:984–989. doi: 10.1038/ng.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato N, Takeuchi F, Tabara Y, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies common variants associated with blood pressure variation in east Asians. Nat Genet. 2011;43:531–538. doi: 10.1038/ng.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim X, Ong RT, Suo C, et al. Transferability of type 2 diabetes implicated Loci in multi-ethnic cohorts from southeast Asia. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemo A, Gerry N, Chen G, et al. A genome-wide association study of hypertension and blood pressure in African Americans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles BA, Doumatey A, Huang H, et al. The roles of IL-6, IL-10, and IL-1RA in obesity and insulin resistance in African-Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E2018–E2022. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda K, Miyake K, Horikawa Y, et al. Variants in KCNQ1 are associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1092–1097. doi: 10.1038/ng.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unoki H, Takahashi A, Kawaguchi T, et al. SNPs in KCNQ1 are associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes in East Asian and European populations. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1098–1102. doi: 10.1038/ng.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg NA, Huang L, Jewett EM, Szpiech ZA, Jankovic I, Boehnke M. Genome-wide association studies in diverse populations. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:356–366. doi: 10.1038/nrg2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo YY, Small KS, Kwiatkowski DP. Methodological challenges of genome-wide association analysis in Africa. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:149–160. doi: 10.1038/nrg2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna S, Li B, Mulas A, et al. Fine mapping of five Loci associated with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol detects variants that double the explained heritability. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo YY, Ong RT, Sim X, Tai ES, Chia KS. Identifying candidate causal variants via trans-population fine-mapping. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:653–664. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suo C, Xu H, Khor CC, et al. Natural positive selection and north-south genetic diversity in East Asia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:102–110. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, et al. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010;467:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature09298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer KA, Ballinger DG, Cox DR, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CC, Su Z, Donnelly P, Marchini J. Designing genome-wide association studies: sample size, power, imputation, and the choice of genotyping chip. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo YY, Fry AE, Bhattacharya K, Small KS, Kwiatkowski DP, Clark TG. Genome-wide comparisons of variation in linkage disequilibrium. Genome Res. 2009;19:1849–1860. doi: 10.1101/gr.092189.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo YY, Small KS, Fry AE, Wu Y, Kwiatkowski DP, Clark TG. Power consequences of linkage disequilibrium variation between populations. Genet Epidemiol. 2009;33:128–135. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler D, Hirschhorn JN, Klannemark M, et al. The common PPARgamma Pro12Ala polymorphism is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2000;26:76–80. doi: 10.1038/79216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant SF, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, et al. Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2006;38:320–323. doi: 10.1038/ng1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Steinthorsdottir V, et al. Two variants on chromosome 17 confer prostate cancer risk, and the one in TCF2 protects against type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V, et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:579–589. doi: 10.1038/ng.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:638–645. doi: 10.1038/ng.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LJ, Mohlke KL, Bonnycastle LL, et al. A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science. 2007;316:1341–1345. doi: 10.1126/science.1142382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LJ, Bonnycastle LL, Willer CJ, et al. Association of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) variants with type 2 diabetes in a Finnish sample. Diabetes. 2006;55:2649–2653. doi: 10.2337/db06-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees SD, Bellary S, Britten AC, et al. Common variants of the TCF7L2 gene are associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a UK-resident South Asian population. BMC Med Genet. 2008;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.