Abstract

Introduction

Early diagnosis of children living with HIV is a prerequisite for accessing timely paediatric HIV care and treatment services and for optimizing treatment outcomes. Testing of HIV-exposed infants at 6 weeks and later is part of the national prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV programme in Zimbabwe, but many opportunities to test infants and children are being missed. Early childhood development (ECD) playcentres can act as an entry point providing multiple health and social services for orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) under 5 years, including facilitating access to HIV treatment and care.

Methods

Sixteen rural community-based, community-run ECD playcentres were established to provide health, nutritional and psychosocial support for OVC aged 5 years and younger exposed to or living with HIV, coupled with family support groups (FSGs) for their families/caregivers. These centres were located in close proximity to health centres giving access to nurse-led monitoring of 697 OVC and their caregivers. Community mobilisers identified OVC within the community, supported their registration process and followed up defaulters. Records profiling each child's attendance, development and health status (including illness episodes), vaccinations and HIV status were compiled at the playcentres and regularly reviewed, updated and acted upon by nurse supervisors. Through FSGs, community cadres and a range of officers from local services established linkages and built the capacity of parents/caregivers and communities to provide protection, aid psychosocial development and facilitate referral for treatment and support.

Results

Available data as of September 2011 for 16 rural centres indicate that 58.8% (n=410) of the 697 children attending the centres were tested for HIV; 18% (n=74) tested positive and were initiated on antibiotic prophylaxis. All those deemed eligible for antiretroviral therapy were commenced on treatment and adherence was monitored.

Conclusions

This community-based playcentre model strengthens comprehensive care (improving emotional, cognitive and physical development) for OVC younger than 5 years and provides opportunities for caregivers to access testing, care and treatment for children exposed to, affected by and infected with HIV in a secure and supportive environment. More research is required to evaluate barriers to counselling and testing of young children and the long-term impact of playcentres upon specific health and developmental outcomes.

Keywords: HIV and AIDS, orphans and vulnerable children, community based interventions, paediatric HIV, care and support, PMTCT, capacity building, early childhood development, participatory methods

Introduction

The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Zimbabwe continues to result in increasing numbers of children affected and infected by HIV and AIDS, a situation exacerbated by high levels of poverty and malnutrition. Children living with HIV comprise 10% of all those infected in Zimbabwe [1], with HIV-related deaths accounting for 40.6% of all deaths among children under 5 in Zimbabwe [2]. With an estimated 1.3 million orphans, Zimbabwe has one of the highest prevalence of orphaning in the world, with an estimated 77% being orphaned by AIDS [3].

While the significant increases in survival for HIV-infected children who have early access to diagnosis and treatment are known [4], early infant diagnosis (EID) programmes have been a challenge to implement in low-resource settings [5]. Improved coordination between prevention of vertical transmission, childhood malnutrition [6] and other maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) services is required to increase access to paediatric HIV diagnosis, improve patient retention and reduce delays in initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) [7]. Culturally sensitive efforts to identify and address the reasons for poor uptake and loss to follow up of EID are required for optimal outcomes for HIV-exposed children [8,9]. Children affected by HIV also face multiple risks to their education and psychosocial wellbeing in their families and communities [10].

The Organisation for Public Health Interventions and Development (OPHID) is a local trust that develops and implements innovative approaches and strategies to strengthen MNCH services in Zimbabwe, providing enhanced access for communities to comprehensive prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) and HIV treatment and care. OPHID has been working closely with the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare since 2001 to support the national PMTCT programme in three provinces of Zimbabwe. Within this work, there is considerable scope for community involvement, not only in promoting uptake of ANC care and HIV testing and treatment, and assisting in adherence to ARV prophylaxis, but also in accessing postnatal PMTCT services and minimising stigma and discrimination attached to HIV and AIDS in the community. In Zimbabwe, community-based support to date has largely focussed on orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) aged from 7 to 18 years [11,12]. Published data [13,14] as well as OPHID observations from programme implementation underscored that little attention was focused on the health, development and psychosocial needs of children under 5 years affected and infected by HIV in their rural communities.

The community-based community-run approach

Towards the end of 2009, seeing it as a natural progression in postnatal HIV prevention and care, OPHID seized the opportunity to extend the PMTCT continuum of care and treatment to rural children under 5 years of age affected and infected by HIV, their families and carers. An informal inventory of needs among this group indicated that many children have limited or no access to: paediatric HIV testing and treatment; adequate nutrition; psychosocial and early learning support; secure and supportive adult caregiver relationships; social protection; birth registration required also for school enrolment; and vaccinations. The resulting community project to support the wellbeing of children under the age of 5 years living with and affected by HIV and AIDS was developed in partnership with the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare. Activities were designed in accordance with existing policy and conducted under the supervision of the Ministry of Public Services, Labour and Social Welfare.

The objectives of the project were to provide health care, social protection and psychosocial support services to children aged younger than 5 years affected and infected by HIV through the formation of community-based and community-run playcentres; to follow up and increase access to care, treatment and support to HIV-exposed and HIV-infected children; to build the capacity of parents, caregivers and families to provide HIV care and support to children below the age of 5 years affected and infected by HIV; and to strengthen the capacity of the surrounding communities supporting the playcentres in HIV prevention, care and support to children affected and infected by HIV.

The aim of the paper is to provide a description of the design and implementation of OPHID's community-based early childhood development playcentre project in order to highlight the benefit of using transparent, participatory approaches in programmes intended to support vulnerable children in HIV-affected communities. The scope of the results is limited to routinely collected programmatic data. Nonetheless, it is useful to inform considerations for future community-based programmes seeking to provide comprehensive HIV prevention, treatment, care and support to vulnerable children 5 years and younger in rural low- and middle-income high HIV prevalence settings, as well as future areas of research.

Methods

The project was developed as an addition to ongoing activities by PMTCT programme partners in response to expanded access to paediatric testing and treatment of HIV and in the absence of data on high quality community-based intervention studies to support the psychosocial and health needs of children affected by HIV [10,12,15]. Accordingly, the playcentre project was developed through experience as an extension of existing activities and not designed with an intervention protocol as a piece of operational research. All data collected during the course of the project were done through routine registers. The methods and results describe important stages of development and trends captured through OPHID's implementation experience.

Project design intended to build ownership of playcentres at all levels

For the project to be relevant to the needs of the communities, sustainable and have maximum impact on ending and treating paediatric HIV, it was important to facilitate national, provincial, district and community ownership of the playcentre project. Support for the playcentre model was first obtained from the relevant Government Ministries at national and provincial levels. OPHID project coordinators then carried out sensitization meetings in three districts with the relevant district and local government offices.

Once district-level support had been obtained, rapid assessments in the form of interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted at local levels to identify the appropriate psychosocial support (PSS) services that needed to be established. Rapid assessments also identified existing OVC services in the district for the under-fives and their geographical coverage; gaps in existing programme coverage; and inventoried any existing community-based initiatives and support structures for OVC under-five. The final purpose of these assessments was to identify existing community structures that could be used to set up the play centres.

Community Nursing Sisters, Child and Social Welfare Officers, council representatives and local leaders, who had been sensitized, participated in the identification of appropriate central community spaces for the location of the playcentres. The preferred sites were in close proximity to the health centres. Terms of reference were drawn up for the group facilitators, child-minders and community mobilisers for each playcentre and suitable individuals from the community were identified to participate in playcentre development and daily operations, for example, people living with HIV (PLHIV), members of women's clubs and church groups, village health workers, community-based carers and youth and peer educators. Once the sites were agreed upon by the community, sensitization meetings were held with the surrounding communities with the support and assistance of local gatekeepers, chiefs, headmen, councillors and even the police. These meetings targeted parents and caregivers of OVC younger than 5 years of age and focussed on the importance of following up and supporting the children from the PMTCT programme and other vulnerable children in the community.

Selection and training of community cadres

Final selection of the community cadres was made with the assistance of the Community Sister and the clinic nurses from the clinics adjacent to the playcentre sites. Interviews were conducted to select the cadre, reviewing literacy levels and an understanding of the concept of volunteerism and passion and suitability for working with small children, and OVC in particular. Many of those selected were people living with HIV. Training workshops were conducted by OPHID's two project coordinators and the EGPAF project officer with assistance from the community nursing sisters utilising the National Psychosocial Support Guidelines for Children Living with HIV and AIDS 2009 [1] and the National Psychosocial Support Training Manual for Children Living with HIV and AIDS 2009 [16]. Each team agreed upon the times and days of operation of their playcentres, usually three mornings a week. The community volunteers were given a small monthly incentive. Each cadre was supplied with a uniform and aprons and hats were provided for the children, and these proved to be important symbols of playcentre ownership.

Setting up and running the playcentres

During the training workshops, the community cadres developed their community-based meaning of OVC and how to identify those most in need using a process outlined by the Programme of Support to the National Action Plan for Orphans and Vulnerable Children (2008), which defined orphans as children 0 to 18 years, who have lost one or more parents [17]. The definition of vulnerability was all children with unfulfilled rights, with specific vulnerability characteristics chosen or adapted by community stakeholders according to their context based upon a list provided in Box 1.0. Under this broad definition, the vast majority of children living in rural settings in Zimbabwe would be considered to be vulnerable.

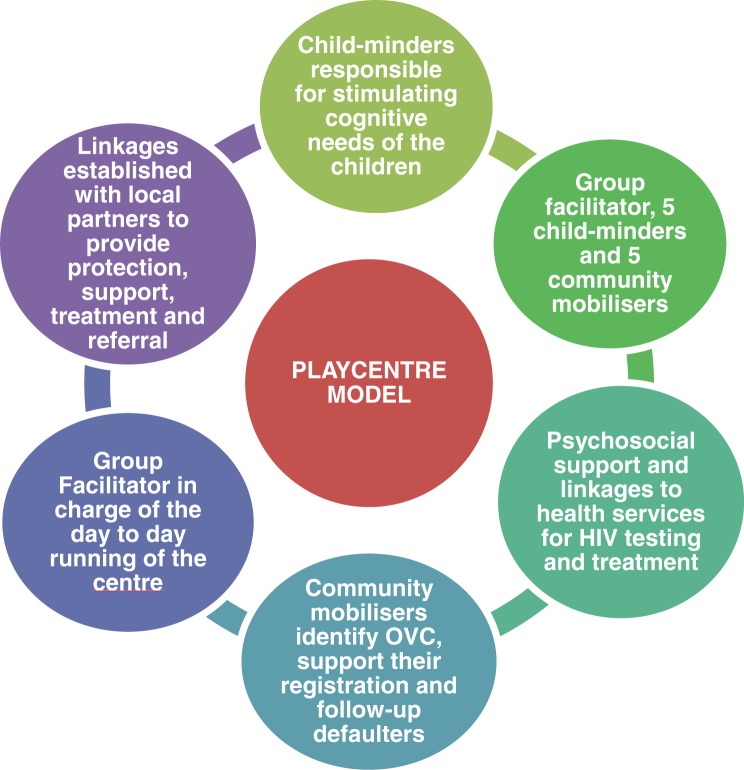

Following the community sensitization meetings informing caregivers of the playcentre's availability and purpose, community mobilisers also engaged in active identification of marginalized vulnerable children in their respective communities to offer them registration. OPHID supplied cleaning materials, basic stationery, mugs and appropriate equipment for supplying each child with a nutritious drink, maheu, and corn-soya porridge. A limited number of early learning wooden puzzles and toys, handmade by local carpenters, were distributed equally to the centres. Additionally, the communities contributed various toys made out of recycled materials including balls, dolls, wire toys and rattles. Parents and carers were taught how to make toys out of locally available materials. The group facilitators and child-minders provided age- and stage-appropriate learning through play activities and psychosocial support to the children at the centres (see Fig. 1 for playcentre model). At registration, following signed informed consent by caregivers (in the case of child-headed households, the extended family or community-appointed guardian) to access the child's health records, information held on the Child Health Card (provided to all children at birth) and the Patient Card (for children with major health problems, including those living with HIV) was recorded for each child.

Figure 1.

Playcentre model.

Box 1.0. NAP definition of vulnerability (2008).

Children who are destitute from causes other than HIV/AIDS

Children with one parent deceased

Children with disabilities

Children affected/or infected with HIV/AIDS

Abused children

Working children

Destitute children

Abandoned children

Children living on the streets

Married children

Neglected children

Children in remote areas

Children with chronically ill parents

Child parents

Children in conflict with the law

Other definitions by communities

Regular site visits were made to the playcentres by the project coordinators to monitor the running of the centres and provide additional on-the-job training and support to the community cadres and check on the wellbeing of the children. Nurses from the adjacent clinics regularly checked on the children's health and nutritional status and those needing care were responded to immediately. Records were kept by the group facilitators profiling each child's attendance, family circumstances, age-appropriate weight-for-height development, health status (including illness episodes), vaccinations, HIV exposure and infection status using national National Action Plan (NAP) for OVC registers (Activity Report Book, Medical Services Register and Chronic Care Register). The information captured on these registers was reported back to the District AIDS Council (DAC) on a monthly basis for forwarding on to the National AIDS Council (NAC) and finally to the Ministry of Labour, Public Services and Social Welfare.

Children with special needs were referred for the requisite support. After the initial recruitment by the community mobilisers, any children defaulting from the playcentres were followed up with a home visit from the community mobilisers. These community mobilisers were also responsible to the nurses at the clinics for following up mother-baby pairs within the PMTCT programme, as well as emphasising the importance of adherence to ARVs and care protocols and immunization of the children in their communities.

Through the FSGs formed at each playcentre for the carers and parents of these children, topical issues encompassing a holistic approach to childhood health and development were addressed. Emphasis was also placed on the health and welfare of families and appropriate linkages to community services were established at each FSG meeting. The importance of all family members knowing their HIV status and accessing treatment and care where required was promoted, with clinic nurses providing counselling and rapid testing for HIV, though service uptake by other family members was not a prerequisite for children to attend services. Access to HIV care and treatment was provided, and there were also opportunities for vaccinations and obtaining birth certificates.

Ethics in the playcentre model

All efforts were made to ensure that the rights of participating children were upheld at all stages of project design and implementation. Numerous checks and balances were integrated into programme design, including collaboration with the Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare and relevant actors in child services at provincial, district and local levels throughout the playcentre project. To avoid HIV-related stigma, children were not recruited according to orphan or HIV-exposure status. Rather, children were recruited as a function of “vulnerability,” the definition of which was developed by the community itself and was suitably broad to encourage inclusion of children facing many different forms of vulnerability (i.e., children with disabilities, children with ill parents (not HIV-specific), abused children, children living with relatives and children in abject poverty). The caregivers and/or guardians of all participating children signed informed consent forms prior to any medical records being accessed and all workers and volunteers involved in playcentre activities signed confidentiality agreements.

Results and Discussion

The results described represent programme data captured from February 2010 to September 2011. All descriptive data used to provide depth to reported figures were captured from informal interviews with staff and volunteers during project implementation.

Profile of the playcentres

The 16 rural playcentres were staffed by 176 community volunteers, the majority of whom 155 were female. Volunteer commitment was high, with an attrition rate of only 4% over the 18-month reporting period; 697 children were enrolled into the playcentres over the reporting period. Social and demographic characteristics of children attending can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Individual and household characteristics of children enrolled in playcentres June 2010 to September 2011 (N=697).

| Age (in years) | 0 to 2 | 3 to 5 | 6 + | Age not recorded | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | 16 (2.3%) | 252 (36.2%) | 8 (1.1%) | 6 (0.9%) | |

| Boys | 12 (1.7%) | 255 (36.6%) | 7 (1.0%) | 4 (0.6%) | |

| Orphan status | Both alive | Single orphan | Double orphan | No data | |

| Girls | 169 (49%) | 125 (36%) | 42 (12%) | 12 (3%) | |

| Boys | 177 (51%) | 118 (34%) | 39 (11%) | 15 (4%) | |

| Family living status | Both parents | One parent | Caregiver | Child headed | No data |

| Girls | 128 (37%) | 110 (32%) | 95 (27%) | 4 (1%) | 11 (3%) |

| Boys | 129 (37%) | 92 (26%) | 110 (32%) | 3 (0.9%) | 15 (4%) |

| Immunization status | Up to date | Not up to date | No data | ||

| Girls | 311 (89%) | 22 (6%) | 15 (4%) | ||

| Boys | 318 (91%) | 16 (5%) | 15 (4%) | ||

The majority of children were of preschool age between 3 and 5 years (n=580, 83.2%), reported having both parents living (n=346; 50%), though only 37% reported living with both parents (n=257). In terms of preventive health measures, after joining the health centres and being linked up with primary health care, 90% of the children enrolled at the playcentres were up to date on their immunizations (n=629), with their vaccination schedule completed, surpassing the full immunization coverage rate for children in Zimbabwe, which is around 75% [18].

Anecdotal reports from project staff and volunteers indicate face-value improvements in growth and physical strength as well as improvements in confidence and interaction due to play therapy and supplementary feeding. These observations require more rigorous study, and characteristics of all participating children are now recorded using the Child Status Index (CSI) instrument for assessing the wellbeing of OVC [19]. There are approximately three or four children per centre with varying degrees of mental or physical disability (e.g., deafness, cerebral palsy or Down's syndrome). These children have been linked to rehabilitation departments in local health centres, relevant government services and NGOs that assist children with special needs. A breakdown of playcentre costs and inputs provided by the community can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Running costs for an OPHID-facilitated playcentre.

| Items | Unit costs for one playcentre for 1 month ($USD) |

|---|---|

| Allowances for group facilitators×1 | 40.00 |

| Allowances for child-minders×5 | 150.00 |

| Allowances for community mobilisers×5 | 150.00 |

| Maheu nutritional supplement for children | 20.00 |

| Corn-soya porridge for children | 40.00 |

| Stationery | 10.00 |

| Cleaning materials | 65.00 |

| Total | 475.00 |

Follow up and access to care, treatment and support for HIV-exposed and HIV-infected children

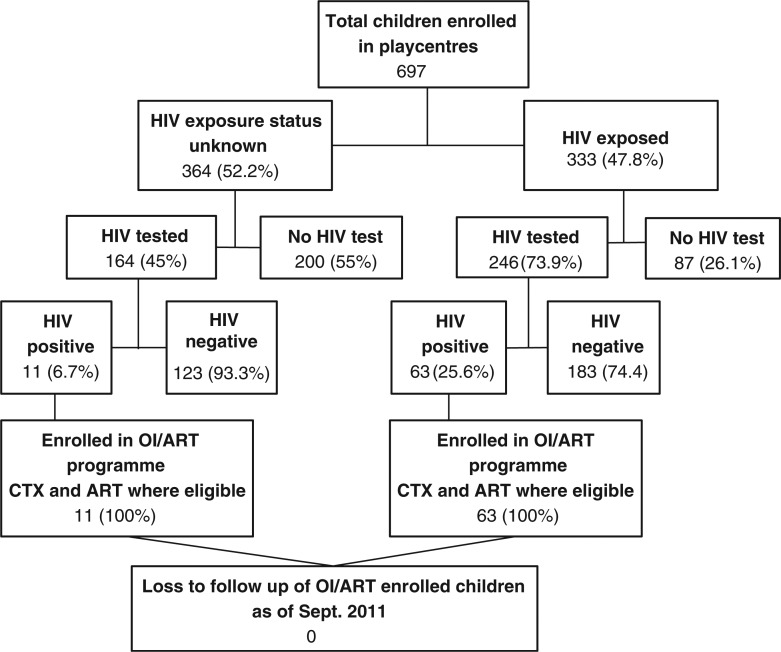

Figure 2 demonstrates the flow of children enrolled in playcentres through the process of determining HIV-exposure status, HIV testing and subsequent OI/ART programme enrolment and retention. HIV exposure status could not be reliably ascertained for children for whom parent-held Child Health Cards records were unavailable (on which HIV-exposed status is recorded in code), particularly for those whose parents had died and cause of death was unknown. Fifty-nine percent (n=410) of children enrolled in the playcentres were tested for HIV. HIV testing always required the consent of the caregiver or guardian and could only be considered when it was in the best interest of the child, that is, that the child would benefit from treatment and would not be stigmatized, discriminated against or isolated.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of playcentre children HIV exposed, tested, positive and treated.

All children diagnosed as HIV seropositive successfully progressed from diagnosis to treatment (n=74). Every child who was diagnosed HIV positive was enrolled in an OI/ART programme and began taking prophylactic doses of cotrimoxazole (CTX). Those children who were deemed ART eligible were all initiated on ART and their adherence to treatment monitored by the playcentre volunteers and the nearest health centre nurse. The use of standardized registers acted as a successful method for preventing loss-to-follow up as the carers of children who were recorded as not having received their medications in the Chronic Care Register were visited at home and offered support and assistance by community mobilisers. With all 74 children found to be HIV-positive recorded as retained within OI/ART programmes and up-to-date with medication prescriptions, it is clear that the value of the playcentre model is not only for identifying children exposed to HIV and ensuring testing but also for following through to ensure programme enrolment and treatment initiation and adherence in a supportive environment.

Build the capacity of parents, caregivers and families to provide HIV care and support

Together with the project coordinators and group facilitators, nurses from the adjacent health centres facilitated capacity building information and education sessions with FSGs, according to a curriculum devised in consultation with each FSG. These sessions focussed on nutrition, family health issues, child protection, family planning, the importance of PMTCT, adherence to care and treatment and immunization. The FSGs were instrumental in providing information and support to parents and caregivers on seeking HIV testing for themselves and their children, as successfully demonstrated by 410 children within the playcentres being tested for HIV, with all those who tested HIV positive children channelled into treatment and care. FSG members also received nutritional information from the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare nutrition officers, reportedly understood the importance of good nutrition choices and were seeking to provide more nutritious food for their children.

In order to reinforce psychosocial support provided to the children at the playcentres, our strategy has been to strengthen the capacity of family caregivers through FSGs, to have the required skills and information to provide better care for their children. Anecdotal evidence suggests that these playcentres and the accompanying FSGs have provided an entry point for HIV services for the caregivers of registered children and other family members. While project reports indicate FSG activities were successful at building the capacity of caregivers with knowledge and skills to increase child health including HIV care and support, such observations require more rigorous study. Attention has now turned to the sustainability of the playcentres and training in income generating activities for the volunteers and carers, to reduce their own economic vulnerability and support the playcentres.

Strengthen the capacity of the surrounding communities supporting the playcentres, on HIV prevention, care and support to children affected and infected by HIV

The continued community response and assistance in the establishment and maintenance of the playcentres indicates community responsibility and ownership of these centres. The whole process of sensitization and mobilization has had a ripple effect in disseminating knowledge on PMTCT throughout the communities. Communities have provided labour and material contributions and have made bricks, built thatched shelters, fenced grounds and donated food. There is a waiting list for children to attend the centres. An initial cap of six children per child-minder/group facilitator, that is 36 children per centre, had been placed on the playcentres and demand has already exceeded this with 697 children enrolled.

Limitation of the current study and indications for future research

Systematic data on high quality community-based intervention studies to support the psychosocial and health needs of children affected by HIV are lacking in the literature, an acknowledged limitation of the present findings. Trends identified through routine data collected during the playcentre pilot project indicate favourable health and psychosocial outcomes for participating children, though data collection was not undertaken with a view to developing evidence. This limitation indicates the need for the replication of this model within an intervention protocol for the purpose of providing scientific evidence for impact upon specified outcome variables. Future research required includes capturing health, development and psychosocial outcomes of participating children and changes in health status, knowledge or practices among their caregivers. Cost-effectiveness analyses of the playcentre model in terms of established indicators such as disability adjusted life years (DALY), quality adjusted life years (QALY) and life years (LY) gained also present opportunities to determine if this model is suitable for large-scale replication in rural communities.

Conclusions

In three rural districts of Zimbabwe, this model of community-based, community-run early childhood development playcentres has contributed to national efforts to improve the health and psychosocial wellbeing of vulnerable children 5 years and younger. By extending and complementing the PMTCT programme from health centres into the community, OPHID has addressed some of the currently experienced limitations of providing follow-up services to HIV-exposed infants and their families. Through the support of community-based cadres, vulnerable children, including HIV-exposed infants and their families are identified and channelled into community-based playcentres. Volunteers at the playcentres, aided by professional Health Care Workers, monitor children's growth, ensure access to immunization services and facilitate the referral of known HIV-exposed children and children of unknown serostatus for HIV testing and any further HIV medical care services as required. At the playcentres, all OVC learn through play and benefit from nutrition supplements, have access to health, other special needs services, birth certificates and psychosocial support. These playcentres provide rural communities with an opportunity to impact on the future health and development of their youngest members in a secure and supportive environment.

Even with a model of close, continuous care, not all children could be tested for HIV. More research needs to be done to evaluate barriers to counselling and testing of young children and develop evidence for the impact of the playcentre model on health, development and psychosocial indicators. Finally, in view of the revised WHO 2010 PMTCT Guidelines recommending extended ARV prophylaxis throughout the breastfeeding period (option A), we are extending the model to include provision for comprehensive services for babies from birth to 2 years of age. With the availability of early infant diagnosis in Zimbabwe, it is important to support these mothers and their infants to access comprehensive PMTCT services and to acquire knowledge on raising healthy, happy babies. To address the gap between birth and 2 years, OPHID has recently started a model of mother-baby groups attached to the playcentres to tackle this omission, enrolling mothers during their pregnancy and in the first 2 years of the child's life.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors' contributions

DP made substantial contributions to the conception, design and supervision of the project, analysis and interpretation of the data and drafted the manuscript. PM was involved in the conception, design and coordination of the project and acquisition of the data. TN was involved in the supervision of the project and critically contributed to the article. DC contributed to the conception, design and coordination of the project. KW provided editorial and technical assistance with analysis, interpretation and presentation of the data. BE was responsible for supervision of the project and critical appraisal of the article.

Funding sources

This article was based on a project funded by UNICEF through the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation from 2009-2010. Additional funding to maintain the playcentres in 2011 was provided by USAID through the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation.

References

- 1.Government of Zimbabwe, Ministry of Health and Child Welfare. Harare: MOHCW; 2009. National Psychosocial Support Guidelines for Children living with HIV and AIDS, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation. World Health Statistics 2008 [Internet] 2008 [cited 2012 March 6]. Available from: http//www.who.int/whosis/whostat/EN_WHS08_Table1_Mort.pdf.

- 3.UNICEF. Social protection in East and Southern Africa: a framework and strategy for UNICEF [Internet] 2008. Available from: http//www.unicef.org/socialpolicy/files/Social_Protection_Strategy(1).pdf [cited 2012 March 6]

- 4.Chatterjee A, Tripathi S, Gass R, Hamunime N, Panha S, Kiyaga C, et al. Implementing services for Early Infant Diagnosis (EID) of HIV: a comparative descriptive analysis of national programs in four countries. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:553. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciaranello AL, Park JE, Ramirez-Avila L, Freedberg KA, Walensky RP, Leroy V. Early infant HIV-1 diagnosis programs in resource-limited settings: opportunities for improved outcomes and more cost-effective interventions. BMC Med. 2011;9:59. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahwere P, Piwoz E, Joshua MC, Sadler K, Grobler-Tanner CH, Guerrero S, et al. Uptake of HIV testing and outcomes within a Community-based Therapeutic Care (CTC) programme to treat severe acute malnutrition in Malawi: a descriptive study. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun M, Kabue MM, McCollum ED, Ahmed S, Kim M, Aertker L, et al. Inadequate coordination of maternal and infant HIV services detrimentally affects early infant diagnosis outcomes in Lilongwe, Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(5):e122–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820a7f2f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donahue MC, Dube Q, Dow A, Umar E, Van Rie A. “They Have Already Thrown Away Their Chicken”: barriers affecting participation by HIV-infected women in care and treatment programs for their infants in Blantyre, Malawi. AIDS Care. 2012:1–7. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.656570. iFirst. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyandiko WM, Otieno-Nyunya B, Musick B, Bucher-Yiannoutsos S, Akhaabi P, Lane K, et al. Outcomes of HIV-exposed children in western Kenya: efficacy of prevention of mother to child transmission in a resource-constrained setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54(1):42–50. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181d8ad51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schenk KD. Community interventions providing care and support to orphans and vulnerable children: a review of evaluation evidence. AIDS Care. 2009;21(7):918–42. doi: 10.1080/09540120802537831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilborn L, Apicella L, Brakarsh J, Dube L, Jemison K, Kluckow M, et al. Orphans and vulnerable youth in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe: an exploratory study of psychosocial well-being and psychosocial support programs. Washington, DC: Horizons Program/Population Council; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schenk KD, Michaelis A, Sapiano TN, Brown L, Weiss E. Improving the lives of vulnerable children: implications of horizons research among orphans and other children affected by AIDS. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(2):325–36. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nyamukapa CA, Gregson S, Wambe M, Mushore P, Lopman B, Mupambireyi Z, et al. Causes and consequences of psychological distress among orphans in eastern Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2010;22(8):988–96. doi: 10.1080/09540121003615061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nyamukapa CA, Gregson S, Lopman B, Saito S, Watts HJ, Monasch R. HIV-associated orphanhood and children's psychosocial distress: theoretical framework tested with data from Zimbabwe. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):133–41. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.116038. Epub 2007 Nov 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King E, De Silva M, Stein A, Patel V. Interventions for improving the psychosocial well-being of children affected by HIV and AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD006733. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006733.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Government of Zimbabwe, Ministry of Health and Child Welfare. National psychosocial support training manual for children living with HIV and AIDS, 2009. Harare: MOHCW; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Government of Zimbabwe, Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare. Zimbabwe's programme of support to the national action plan (NAP) for orphans and vulnerable children. Harare: MOHCW; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.UNICEF. UNICEF Zimbabwe Statistics [Internet] 2010 [cited 2012 March 6]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/zimbabwe_statistics.html.

- 19.US Agency for International Development (USAID) Child Status Index: a tool for assessing the well-being of orphans and vulnerable children. USAID; 2009. www.ovcsupport.net/libsys/Admin/d/DocumentHandler.ashx?id=791 [citde 2012 March 6]. Available from: [Google Scholar]