Abstract

Context

Career opportunities for athletic training students (ATSs) have increased substantially over the past few years. However, ATSs commonly appear to be opting for a more diversified professional experience after graduation. With the diversity in available options, an understanding of career decision is imperative.

Objective

To use the theoretical framework of socialization to investigate the influential factors behind the postgraduation decisions of senior ATSs.

Design

Qualitative study.

Setting

Web-based management system and telephone interviews.

Patients or Other Participants

Twenty-two ATSs (16 females, 6 males; age = 22 ± 2 years) who graduated in May 2010 from 13 different programs accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education.

Data Collection and Analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim, and the data were analyzed inductively. Data analysis required independent coding by 2 athletic trainers for specific themes. Credibility of the results was confirmed via peer review, methodologic triangulation, and multiple analyst triangulation.

Results

Two higher-order themes emerged from the data analysis: persistence in athletic training (AT) and decision to leave AT. Faculty and clinical instructor support, marketability, and professional growth were supporting themes describing persistence in AT. Shift of interest away from AT, lack of respect for the AT profession, compensation, time commitment, and AT as a stepping stone were themes sustaining the reasons that ATSs leave AT. The aforementioned reasons to leave often were discussed collectively, generating a collective undesirable outlook on the AT profession.

Conclusions

Our results highlight the importance of faculty support, professional growth, and early socialization into AT. Socialization of pre–AT students could alter retention rates by providing in-depth information about the profession before students commit in their undergraduate education and by helping reduce attrition before entrance into the workforce.

Key Words: socialization, attrition, retention, mentorship

Key Points

Senior athletic training students who persisted in athletic training did so because of faculty and clinical support, improved marketability, and professional growth.

A shift of interest away from athletic training, lack of respect for the athletic training profession, compensation, time commitment, and athletic training as a stepping stone led senior athletic training students to leave athletic training.

From the beginning of athletic training in the 1950s to the present day, a primary concern has involved the education of students and working professionals.1,2 The concern is evident with the marked growth of professional (entry-level) athletic training education programs (ATEPs), postprofessional programs, and continuing education programs.2–4 Both the professional and educational opportunities for the athletic trainer have increased substantially over the past few years and will continue do so in the future.5–7 Currently, 347 undergraduate programs are accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE), and this number has grown substantially since the transition away from the internship route to certification.3,5,6

The National Athletic Trainers' Association5 (NATA) estimates it has more than 5000 student members; however, only 600 members are certified graduate students, and overall approximately 1200 are certified members in their first year of employment, indicating attrition away from the profession. The dichotomy in these statistics raises the question of what professions or courses of study these students, who are enrolled in CAATE-accredited ATEPs, planned to pursue after completing their programs. Although a plethora of data exists regarding student retention in higher education programs,8–10 a paucity of research exists on those students who complete degree programs but choose not to enter the workforce in which they were professionally trained. Presently, peer support, clinical educational experiences, and motivation are linked to retaining students in ATEPs,6 whereas stress and burnout predominately lead to attrition for students enrolled in medical and nursing programs11,12 and postprofessional programs.4,13 Athletic training students (ATSs) encounter a stressful and demanding lifestyle as they attempt to balance their academic studies, clinical responsibilities, and personal obligations and interests.14 This stress often leads to burnout among ATSs.15 Perhaps these same factors can influence the decision of an ATS to become an athletic trainer.

After graduation, ATSs have many career options, which can include advanced study in various graduate programs; postprofessional degrees in athletic training; or direct entrance into the workforce via high school, collegiate athletics internships, or outreach positions.4,16 With these diverse options available and no current mandatory course for postprofessional study, understanding how ATSs arrive at this postgraduation decision is important particularly because the statistics demonstrate a clear decline in students becoming athletic trainers.5 A better understanding of the career decision-making process might help increase the number of students who pursue postprofessional educational programs and who become athletic trainers. Neibert et al16 explored the career decisions of senior ATSs and recent graduates of accredited ATEPs. They found that 82.4% of participants pursued a career as an athletic trainer, whereas the remainder indicated they were not seeking employment as an athletic trainer. Although the statistics reveal a large portion of students become athletic trainers, their socialization experiences and the influence of these experiences on their decisions to leave or stay in athletic training are not clear.

Professional socialization is an important and necessary component of an ATS's educational experiences and is often the theoretical framework used to capture a student's development into his or her professional role.7,17–19 As a developmental process, socialization is defined as the process of learning in which an individual acquires the knowledge and skills that enable him or her to function in a particular role.17–19 This process is a fundamental component in the professional preparation of health care providers, including athletic trainers, as they learn the skills, values, attitudes, and norms of behavior associated with their professions.17,20 Mentorship has been identified as a critical factor in the professional socialization development of an athletic trainer because the relationship between the mentor and protégé can help reinforce professional roles, advance skill development, and promote lifelong learning for both members.21,22 Mentorship received during the professional preparation phase can positively or negatively influence the student's evaluation of the profession22 and potentially can influence postgraduation decisions and future career choices.23 Clinical instructors are influential in the socialization process, and their levels of passion and excitement can directly affect a student's overall impression and respect for a given profession.21,23

The roles and responsibilities of the athletic trainer are demanding and complex, and learning how to manage these roles can be daunting at times. Therefore, scholars have begun to critically evaluate the process from a global perspective and the factors that can influence the process. Researchers have a substantial understanding of how students are recruited24 into an ATEP, what factors attract them to a career in athletic training,7 what factors keep them enrolled in ATEPs,6 and how they are socialized after they work in full-time positions18–20,25; however, the understanding of the professional preparation and anticipatory socialization of the ATS and its effect on attrition in the workforce is limited.16 Our hope is to build on previous literature focused on career decisions6,7,16,18,19,21,24,26 and socialization18–21,26,27 and explore the role that professional socialization plays in the career decisions of ATSs.

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to use the theoretical framework of socialization to examine the influences on postgraduation decisions of senior ATSs enrolled in CAATE-accredited ATEPs. The following question guided the data-collection process: Why do ATSs choose to become or not to become athletic trainers?

METHODS

Methodological Framework

Maxwell28 suggested that qualitative methods are appropriate for understanding meanings: understanding contexts in which participants received education and work, understanding thought processes rather than outcomes, and identifying critical influences on attitudes and behaviors. Qualitative methods ultimately can lead to generating theory because they are ongoing, emergent processes.18,29 In studies about career decision of ATSs, researchers have used quantitative methods.16 For a more in-depth understanding of the influences affecting the postgraduation career decisions of senior ATSs, we selected a qualitative approach. Web-based interviewing, including discussion panels, has been used in previous work.30 This method of data collection has many advantages, including the inclusion of a geographically dispersed sample of participants, communication between the researcher and participant at the convenience of the participant, ample time for reflection31 before responding, increased anonymity, and reduction in misinterpretation of the data.30 Moreover, an increasing number of students and professionals are using electronic, Web-based modes of communication. For these reasons, we selected an Web-based qualitative approach using HuskyCT (University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT), which is an online educational medium powered by Blackboard Learning System (Vista Enterprise Edition; Blackboard Inc, Washington, DC), to learn more about the influences on postgraduation career decisions of senior undergraduate ATSs. Follow-up, one-on-one telephone interviews also were conducted after the initial online portion was completed and data were analyzed.

Participants

At the outset of the study, we established predetermined criteria29,32 for study participation, including both male and female ATSs who were in the last semester of their senior years, were enrolled in accredited programs, and were planning to sit for the Board of Certification examination. To gain a holistic perspective about postgraduate decisions, we did not exclude students based on career choice (ie, employment, graduate school, type of graduate study program).

Twenty-two ATSs (6 men, 16 women; age = 22 ± 2 years) who graduated in May 2010 from 13 different accredited ATEPs participated in this study. We realized that studying more female than male participants could cause a sex bias within the responses; however, the NATA5 membership statistics revealed a shift to a more female-dominated membership. Participants represented 7 NATA districts (Table 1). Six (3 men, 3 women) of the 22 initial ATSs agreed to participate in the follow-up telephone interviews.

Table 1.

Individual Participant Demographic Data

| Name |

Age, y |

Sex |

State |

National Athletic Trainers' Association District |

National Collegiate Athletic Association Division of Institution |

Career Decision |

Postgraduation Plansa |

| Scottb | 22 | Male | CT | 1 | I | Persist | Graduate school (athletic training), athletic training graduate assistant |

| Taylorb | 22 | Female | CT | 1 | I | Persist | Graduate school (athletic training), athletic training graduate assistant |

| Bianca | 22 | Female | CT | 1 | I | Persist | Graduate school (athletic training), athletic training graduate assistant |

| Dylanb | 24 | Male | PA | 2 | II | Leave | Physician assistant school |

| Melissa | 22 | Female | PA | 2 | II | Leave | Graduate school (exercise physiology) |

| Wendy | 22 | Female | PA | 2 | II | Leave | Graduate school (education) |

| Colleen | 22 | Female | PA | 2 | II | Persist | Graduate school, athletic training graduate assistant |

| Amanda | 21 | Female | PA | 2 | II | Persist | Graduate school (athletic training), athletic training graduate assistant |

| Laura | 22 | Female | PA | 2 | II | Leave | Physician assistant school |

| Cathy | 22 | Female | PA | 2 | II | Persist | Graduate school (athletic training), athletic training graduate assistant |

| Eliza | 21 | Female | PA | 2 | II | Leave | Nursing school |

| Bailey | 22 | Female | PA | 2 | I | Persist | Graduate school (sports management), athletic training graduate assistant |

| David | 22 | Male | NC | 3 | I | Persist | Graduate school (sports management), athletic training graduate assistant |

| Mackenzie | 24 | Female | NC | 3 | I | Persist | Undecided |

| Elena | 21 | Female | SC | 3 | II | Leave | Occupational therapy school |

| Julieb | 22 | Female | MD | 3 | III | Leave | Nursing school |

| Christopher | 24 | Male | WI | 4 | I | Persist | Graduate school (athletic training), athletic training graduate assistant |

| Nathanb | 21 | Male | MN | 4 | III | Leave | Physical therapy school |

| Kim | 23 | Female | MI | 5 | I | Leave | Graduate school (nutrition) |

| Jackson | 23 | Male | GA | 9 | I | Leave | Dental school |

| Annie | 21 | Female | WA | 10 | I | Persist | Graduate school (athletic training), athletic training graduate assistant |

| Nicoleb | 23 | Female | OR | 10 | I | Persist | Graduate school (athletic training), athletic training graduate assistant |

Information in parentheses refers to the program of study that the student would pursue in graduate school.

Indicates athletic training student participated in the follow-up telephone interviews.

We initially sent e-mails explaining the study and steps for data collection to 75 randomly selected program directors (PDs) in accredited programs to help facilitate enrollment in the study because a database for student members does not exist.18,29,32 We wanted to include a random selection from the 347 programs rather than a stratified sample across district or type of school classification.33 The NATA member services can provide a separate list of student members, but the list does not identify their levels in a program. However, CAATE3 does provide information on all ATEPs in the United States. We compiled a list of all ATEPs and the corresponding information about the PD. After the list was completed, we randomly selected PDs to e-mail from a list generated from CAATE.3 We requested that the PD forward the e-mail to all senior students, and the students directly contacted the investigators. In addition, the researchers capitalized on preexisting professional relationships with PDs to help identify potential participants who met the criteria.29,32 After the initial e-mails, recruitment followed a snowball sampling,29,32 in which the researchers recruited participants. Recruitment of participants ceased after data saturation was obtained.18,29 Data saturation occurred after analyzing our initial pool of 22 interviews. The decision to cease data collection was determined based on an equal distribution of postgraduation career decision (12 decisions to persist, 10 decisions to leave the profession) and an establishment of data saturation. Initial data analysis revealed the 2 major themes (persisting, leaving) and provided more rationale behind the data-saturation process and cessation of participant recruitment. Participants who decided to stay in athletic training were referred to as persisters, and participants who decided to leave athletic training were referred to as leavers. By completing and submitting a background questionnaire, students consented to participation in this study. The ATSs who agreed to participate in a follow-up telephone interview also completed a separate consent form that was e-mailed to them and returned it via fax. The study was approved by the University of Connecticut–Storrs Institutional Review Board.

Setting and Instrumentation

Before students completed the interview questions, they completed a background questionnaire. We used the background questionnaire to collect their demographic data and to provide information regarding their intentions after graduation. The background questionnaire also integrated Likert-scale questions to rate the participants' perceptions of certain characteristics of athletic training. The Web-based portion of the study was conducted via HuskyCT; this learning management software program provides a secure platform for educators to engage in communication with their students. We created the structured online interview guide to answer the research questions based on existing literature about choosing a career in athletic training, retention in athletic training programs, and socialization of athletic trainers (Table 2). A second interview guide was created for the follow-up telephone interviews but was semistructured to allow for expansion on review of the online data (Table 3). A panel of 3 experts comprising qualitative researchers and professional educators who were not authors reviewed the instrument for clarity, interpretability, and design. This step was included to establish content validity of the interview instrument and to establish credibility with the methodologic design. Several changes were made based on the feedback received from the panel of experts and included removing some questions, rewording some questions, and adding some demographic variables. Before data collection, a small pilot study was conducted with a group of 3 ATSs in the same accredited program. The data generated from the pilot study were not used in data analysis but were used to ensure comprehensibility, to ensure readability of the online interview and background questionnaire, and to establish face validity of the online interview. After the pilot study, we made minor changes to the documents, including rewording questions and changing the order of delivery of the interview questions.

Table 2.

Structured Online Interview Guide

| 1. What influenced your decision to study athletic training? | |

| 2. What are your immediate plans after graduation (graduate school, working, leaving the profession)? | |

| 3. Discuss how you arrived at your decision (graduate school, working, leaving the profession)? | |

| 4. When you were making your postgraduation plans who influenced/impacted your decisions? What people did you turn to for advice (professors, clinical instructors, family, friends, significant others, etc)? | |

| 5. Did your postgraduation plans change from when you first entered your academic program? If so, please describe why. If no, please describe why not. | |

| 6. Reflect back on your opinions and expectations of the profession of athletic training before you began your academic preparation. How has it changed now that you are getting ready to graduate and did this impact your postgraduation decision? | |

| 7. Did any of your classmates leave the program before completing the coursework? If “yes,” do you know what factors contributed to them leaving the program early? Are your postgraduation plans different than your current classmates? | |

| 8. From what you have seen throughout your undergraduate education, why do you feel some of your classmates have chosen to not enter the profession of athletic training after graduation? | |

| 9. Do you feel your education and clinical experience have prepared you enough to practice as an athletic trainer? Has this at all influenced your postgraduation decisions? |

Table 3.

Semistructured Interview Guide for Follow-Up Interviews

| 1. What was the major influence behind your reasons to persist in athletic training? Do you see those same influences ever changing? | |

| 2. What was your major reason to leave the profession or never entering in the first place? | |

| 3. Do you have any regret regarding your decision? | |

| 4. Where do you see yourself professionally in 5 years? | |

| 5. Reflect back on your undergraduate experience. Is there anything you would change? Why? | |

| 6. Why do you think so many students go through the process of undergraduate education in athletic training and when they graduate they never use the degree they received? |

Data Collection Procedures

After participants acknowledged interest in the study as described, a cover letter, including a background questionnaire, log-in identification, and password for the interview, was sent to them via e-mail. All participants completed a series of 9 initial interview questions over the course of 1 week. We specifically chose to have participants answer questions at the end of April 2010 because they would be more certain of their postgraduation plans. Questions were posted on Monday and Thursday mornings, and the participants could log in and out and could add to or edit their responses to each question at their own paces. During the week of data collection, participants were sent e-mails notifying them when a new question was posted or reminding them to respond to that day's questions if they had not completed the questions before a new set of questions was posted.

Follow-up interviews were conducted by telephone to clarify findings, gain more in-depth information about the factors influencing career decisions, and substantiate the initial findings. Only 6 participants (3 who were persisting in athletic training and 3 who were leaving athletic training) volunteered to participate in this interview.

When data collection was complete, we cut and pasted the electronic data into a Word (version 2010; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) document for analysis, whereas the follow-up telephone interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. We sent the completed transcriptions via e-mail to the participants as a form of member checking for clarity and accuracy.

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

We inductively analyzed the interview data, borrowing from the grounded theory approach32,34 and from the steps discussed by Pitney and Parker.29 We carefully read the transcripts to gain a holistic sense of the data collected. We identified the key information related to the purpose and research questions established at the onset of the study. Each key piece of information was assigned a label to capture its meaning, and the labels were thematized as emerging categories developed.29,34 Relationships between categories were evaluated and examined and were collapsed together or separated when appropriate. All final themes were reviewed within the research team and with the peer reviewer (W.A.P.), who was an athletic training educator with previous experience with online interviewing and qualitative methodologies.

Trustworthiness was established by peer review, data source triangulation, and multiple analyst triangulation. The peer reviewer evaluated the data and findings as interpreted by the researchers to determine credibility and accuracy with the data-collection process and interpretations. The data collected were triangulated by using multiple forms of data collection, including online interviews, telephone interviews, and background questionnaires. To reduce the possibility of misinterpreting the data, 2 researchers (S.M.M., K.E.G.) independently analyzed the transcripts and discussed the emergent themes.29

RESULTS

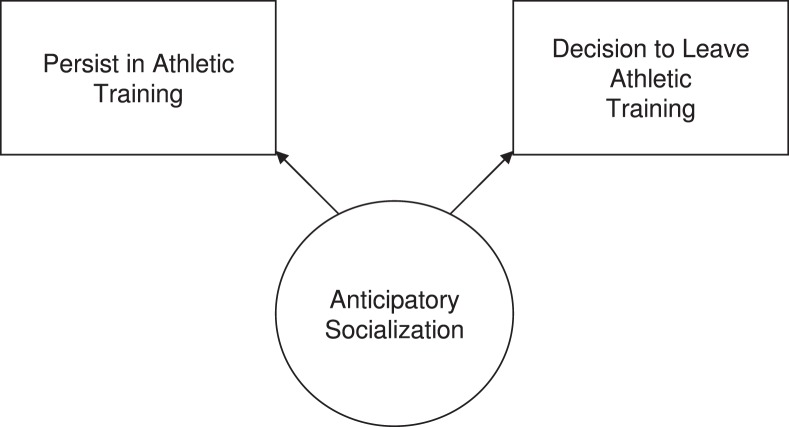

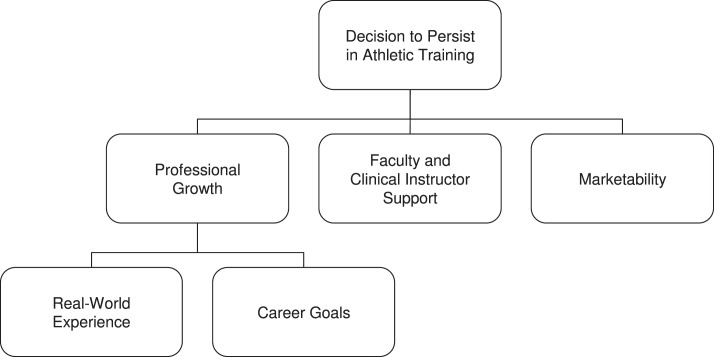

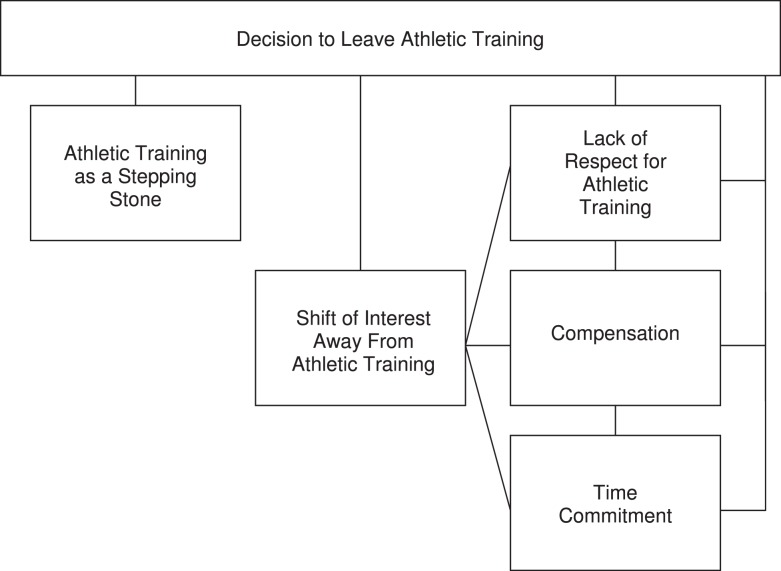

Two higher-order themes emerged from the findings that explained the participants' reasons for and influences on their postgraduation career decisions: persistence and attrition. Figure 1 depicts the role of anticipatory socialization in the emergence of the 2 first-order themes. Anticipatory socialization includes the experiences an individual has before entering the workforce, which can involve both formal and informal professional preparation.17,22 Undergraduate education and professional preparation play a major role in developing postgraduation career decisions of students. Each first-order theme comprised a series of supporting lower-order themes (Figures 2 and 3). The supporting lower-order themes illustrating the reasons to persist in athletic training were (1) professional growth, (2) faculty and clinical instructor support, and (3) marketability. The lower-order themes articulating the decision to leave athletic training included (1) shift of interest away from athletic training, (2) lack of respect for the athletic training profession, (3) compensation, (4) time commitment, and (5) athletic training as a stepping stone. We explain each theme and support it with statements from the participants.

Figure 1.

Influences on athletic training students' postgraduate decisions.

Figure 2.

Factors influencing an athletic training student's decision to persist in athletic training.

Figure 3.

Factors influencing an athletic training student's decision to leave the profession of athletic training.

Persist in Athletic Training

Professional Growth

The lower-order theme professional growth was discussed consistently by multiple participants about their decisions to become athletic trainers. Although its 2 lower-order themes, real-world experience and future career goals, were similar, they were distinct and are discussed in detail.

Real-World Experience

Several of the participants viewed advanced study via graduate school as a means to promote professional growth while still being mentored and supported as a graduate assistant athletic trainer. This reflected commitment to the profession and apprehension to accept the responsibilities of a full-time position. During a follow-up interview, Taylor said: “It [graduate school] acts as a buffer zone before I head into the real world. Just even starting out now, I'm so glad I'm able to have support instead of just being thrown out there on my own.” Bailey highlighted the commitment aspect as her rationale for graduate school: “I am always willing to keep learning new things, and I wanted to broaden my knowledge in the athletic training field. I have a passion for athletic training and plan to continue with it for the rest of my life.” Amanda had a similar sentiment about professional growth and commitment: “I think that in order to be the best athletic trainer I can be, I need more education and guidance. This is why I chose to attend graduate school.” For Bianca, professional growth meant gaining more experience working as a graduate assistant: “I wanted the experience I would gain working as a graduate assistant while I was at grad school.”

Follow-up interviews with the 3 participants who persisted in athletic training confirmed this theme. For them, the selection of graduate school was a means to promote professional growth without the pressures associated with a full-time position.

Career Goals

Pursuit of future or “dream” positions was another driving force behind the postgraduation decisions of this group of ATSs. Graduate assistantships provided the opportunity to gain experience within a clinical setting they hoped to obtain upon graduation. They recognized the need to gain real-life work experience in that setting to be a viable candidate. Mackenzie said: “I decided to go to graduate school because I want to work for either a college or professional team in the future. I feel that in order to get to that level in my career I would need to receive my master's [degree].” When asked why he decided to continue with graduate school, Scott discussed the need to improve and advance his knowledge and skills. During his follow-up telephone interview, he stated:

Education, education, education. Going to the place where I knew I would get, hands down, the best education for a master's program that you can get. And also to get my hands on some research and try to become a better clinician … I think once you graduate undergrad, you know the minimum. I wanted to be better.

Professional growth was consistently discussed by ATSs who were persisting in athletic training and encapsulated the desire to gain more hands-on job training before entering the workforce.

Faculty and Clinical Instructor Support

Participants explained they had a strong sense of support from their faculty and clinical instructors about their postgraduation plans. They relayed that PDs, professors, and clinical instructors played roles in guiding them toward different directions after graduation. Participants agreed that these people and mentors had a large influence in their decisions. For example, Bianca stated: “I think that my postgraduation plans were mostly influenced by my professors and clinical instructors.” This was echoed by Mackenzie, who explained: “My professors and ACIs [Approved Clinical Instructors] at my school had an impact on my decision as to what opportunities were available for me after graduation. They really helped me in this process.”

The participants seemed to receive the biggest influence from professors and clinical instructors when deciding to attend graduate school and further their education. This was articulated by Bailey: “My program director and many of the athletic trainers that I have worked under all persuaded me to go to graduate school. … People who I have worked with in my undergraduate career really influenced that decision.” Taylor relayed the message: “My professors and clinical instructors gave me great advice to go to graduate school.” Cathy also agreed: “My ACIs also had an influence on my attending graduate school; all of them directed me towards getting my master's [degree].”

For Scott, faculty and clinical instructors played a different role by helping him determine specific graduate schools to which he should apply. He stated: “My professors also were very influential in pointing me in the direction of specific schools to look at once I decided to obtain my master's [degree] in athletic training.” The emergent theme of faculty and clinical instructor support reflected helping participants mainly to attend graduate school and persist in the field of athletic training.

Marketability

Marketability was articulated as a means to advance current knowledge through additional educational experiences. This was often in conjunction with a graduate assistantship, and the pursuit of an advanced degree was viewed as a means to diversify their professional strengths to secure a potential job. Nicole stated: “While I know that I can get a perfectly respectable job in athletic training without a master's degree, I want to make myself as marketable as possible.” For both Bailey and Julie, becoming more marketable meant broadening their educations in areas other than athletic training. Bailey said: “I want to broaden my area of knowledge, and I felt that studying sport management was the perfect area.” Julie reinforced this idea, explaining: “In order to make yourself marketable to the masses you need more than one degree. … The field itself is overflowing with people that have dual degrees [or credentials].” The previous quotations speak to the participants' beliefs that employers would value an advanced education that might expand an athletic trainer's abilities.

Decision to Leave Athletic Training

Figure 3 depicts the influences that ATSs articulated as reasons to leave athletic training. In combination, lack of respect for the athletic training profession, compensation, and time commitment appeared to be fundamental reasons to leave athletic training for this group of students. Ultimately, these elements of the profession, as viewed by the student, caused a shift of interest away from the athletic training profession or, in essence, detracted from their wanting a career in the profession. Athletic training students who spoke of using athletic training as stepping stone to another medical or health care profession did comment on the factors of respect, compensation, and time commitment, but because of their professional goals, they were less troubled about them. Using athletic training as a stepping stone often was viewed as a separate reason to leave athletic training, and the challenges that we mentioned were recognized by the participants but were not of concern.

Shift of Interest Away From Athletic Training

A shift of interest away from athletic training was a realization of the participants through their academic and clinical exposure to the roles and responsibilities of an athletic trainer that the profession did not match their personal interests and ultimate career goals. This was the case for Wendy, who stated:

I am leaving the profession for a different profession because through internship experiences, I realized that my ability to remain calm and think clearly during high-stress (injury) times is not great. I find it very difficult to react to certain high-stress times in a clear manner where I will need to be the person being relied on.

Although opting to remain in the profession, other participants discussed attrition among classmates that was due to the realization that the profession was not what was originally anticipated or understood or that their undergraduate experiences did not match their expectations. The clinical education experiences then provided insights that a career in athletic training was not a match for them. For example, David said: “I had many classmates who decided to drop out of the athletic training program. A lot of the reasons seemed to be that students were not aware of what was involved in the athletic training program.” Mackenzie recalled similar observations, stating: “I have seen many [peer] students leave. … I think a lot of students don't understand what the [athletic training] program will consist of when they first decide to apply for the program.” Eliza explained: “There have been a large number of people who have dropped out of the major [athletic training]. People have just realized that this profession was not for them. I don't think many people realize the work that goes into being an athletic trainer.”

Annie said: “Several of my classmates left the program throughout my time in college. I do not know all of the reasons behind this, but for the most part it was due to a realization that this was not the profession for them.” Bailey echoed this statement: “I feel that some students had chosen not to enter the profession of athletic training after graduation because they thought it was something different from what it was.”

Follow-up interviews reaffirmed this theme. Nathan, who was leaving the profession, discussed the commitment necessary and the misconceptions regarding the profession:

Students are leaving the athletic training field because I think that students don't really understand the investment involved in being an athletic trainer. … Athletic training students realize that athletic training is not for them, and it is not just about hanging around athletes.

The process of being socialized into the profession of athletic training allowed many of the participants to discover the expectations, roles, and responsibilities were no longer of interest to them.

Lack of Respect for the Athletic Training Profession

Several participants revealed that they misunderstood the job description and responsibilities of an athletic trainer. Through their educational experiences, some participants learned that the public and medical community did not completely understand or respect the role of the athletic trainer in health care, and this knowledge concerned them. This lack of respect for the profession of athletic training caused a few participants to leave athletic training for other, more respected careers. For example, Jackson said: “I would like to practice a profession that was more respected among the entire population and medical population.” Both Dylan and Bailey believed that athletic trainers received little respect from others. Dylan stated: “I did not like the amount of respect athletic trainers received from their superiors.” Bailey said: “I know a lot of them [classmates] didn't like how they were looked down upon by doctors and other health professionals.” The views of Mackenzie involved the perception of athletic trainers: “I find that many people do not take athletic trainers seriously.”

Participants expressed the combination of lack of respect for athletic training and compensation as a reason for them to leave the profession. In a follow-up interview, Dylan was asked, “What was the number one reason you decided to not pursue athletic training?” He responded: “Hands down, the lack of respect and the amount of money made.” For some participants, lack of respect manifested itself in not being adequately compensated for the work performed by an athletic trainer. For others, compensation alone was the primary reason for not persisting in the profession.

Compensation

Compensation refers to the salary and benefits of an athletic training position regardless of clinical setting. Several of the participants discussed the disparity between the salaries of athletic trainers and those of other allied health and medical care providers. For Laura, compensation was the direct cause for her leaving athletic training. She candidly stated: “Salary was a big determinant to leave [athletic training]. As a PA [physician assistant] I will make SIGNIFICANTLY more than an athletic trainer.” Most participants agreed that athletic trainers receive low pay, especially in relation to the amount of work and hours related to their abilities to meet their professional responsibilities. For example, Dylan said: “Athletic training salaries could be a lot higher than what they are for the amount of work you put into it. … I think athletic training honestly hurts itself because it opens up a lot more opportunities to other routes that pay more.” Wendy agreed, noting: “Some people want to move on to better paying jobs with better hours and more recognition.” Although not opting to leave, 2 participants discussed having classmates deciding to leave athletic training because of low compensation. Amanda explained: “As stated by most of my classmates, it's mostly about compensation. Athletic trainers don't make much money. … The low pay has driven a majority of my classmates away from the profession.” Nathan reinforced this comment by stating: “Some students are pursuing other health careers because of the lack of money in athletic training and the long hours required.” During a follow-up interview, Scott reinforced this concept about his classmates when asked why so many students leave athletic training. He explained: “Sometimes I think it just comes down to money. We don't get compensated for the rigorous schooling that we go through and the amount of knowledge that we actually have.”

Participants also expressed their concerns about compensation in athletic training in a Likert scale included in the background questionnaire. All of the Likert-scale questions, means, and standard deviations are presented in Table 4. On average, participants rated income and salary compared with amount of work performed as 3.7 on a scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 10 (excellent). This highlights the finding that the participants perceive athletic training as a low-paying job, which influences their decisions to persist within the profession.

Table 4.

Likert Scalea Data Rating Characteristics of Athletic Training

| Question |

Mean ± SD |

| 1. Number of hours worked per week | 4.7 ± 2.6 |

| 2. Job- and work-related stress | 4.9 ± 2.3 |

| 3. Ability to balance life (school, family, personal time, etc) | 5.2 ± 2.5 |

| 4. Chances for career progression and development | 7.1 ± 2.7 |

| 5. Income and salary compared with amount of work performed | 3.7 ± 2.0 |

| 6. Quality of education and clinical experience you received | 8.6 ± 1.4 |

Indicates students evaluated each statement on a 10-point Likert scale with the anchors of 1 (poor) and 10 (excellent).

During their educational preparation, participants were introduced to a profession that is not compensated appropriately for the professional demands and hours necessary to complete job-specific responsibilities. They might not have had this knowledge and understanding until they enrolled in an academic program.

Time Commitment

Participants expressed the concern that athletic training involved an extensively large time commitment that usually was controlled by someone other than the athletic trainer. For example, Jackson stated: “I do not want a job that requires me to work an insane amount of time, requires me to be available to someone at all times. …” Mackenzie added: “I have realized that athletic training is a lot of hard work and consists of very long hours.” Some expressed the concern that they could not see themselves being an athletic trainer for the rest of their lives. Wendy commented: “I do not wish to spend so many hours and overtime hours working when I plan to have a family.” As with compensation, time commitment was evaluated on a Likert scale. On average, participants rated the number of hours worked per week as 4.7 out of 10. The low rating shows that time commitment can contribute to why ATSs leave athletic training.

Other participants explained what they understood to be reasons why their classmates chose to leave athletic training. Amanda said: “Most of them [classmates] left because of the enormous time demands. They would have to make sacrifices with other activities to stay in the program.” Cathy reiterated: “Some of my classmates dropped out simply because of the time commitment of practices, traveling, etc.” According to Dylan: “A lot of our classmates that switched to another major were either too lazy or did not like the time commitment. … Time was a major factor for most people.”

Stepping Stone

Stepping stone was defined as using a degree in athletic training to provide training and a background for another degree program, such as medicine, physician assistant, or doctor of physical therapy. This theme also encompasses the understanding that a person never wants to use the skills learned to become an athletic trainer but wants to use them as a catalyst for professional growth. For example, Christopher discussed the intentions of his peers regarding a degree in athletic training:

My classmates going onto PT, PA, and medical school wanted to do that before athletic training. They wanted to get their undergraduate degrees in athletic training because that is what interested them and they felt that they could use their undergraduate education as a resource in their future endeavors.

Julie agreed, saying: “I always knew that I would not work as an athletic trainer and that it was a stepping stone for me. … My athletic training background could help propel me through nursing school.”

Two participants explained they enjoyed athletic training, but they wanted to learn more in specific areas so they would have more opportunities. Elena said: “I chose occupational therapy because I find it to be much related to athletic training, while at the same time, it opened up many more opportunities for me and still gives me a master's [degree].” Nathan echoed Elena's thoughts: “After my athletic training schooling, I really feel compelled to learn more, and I felt like physical therapy would be the best way for me to expand my knowledge.”

Follow-up interviews confirmed that athletic training was viewed as a stepping stone for another medical profession, particularly because the degree programs that were being pursued after graduation do not offer undergraduate course work. Julie put it best, saying:

I think maybe a lot of people use it [athletic training] as a stepping stone. Athletic trainers are so underrepresented. They take for granted what we do, how hard we work, and what we need to do. The sad thing about it is that you just can't go out and do athletic training. I feel like you need athletic training plus another certification or 2 certifications to even be competitive in the job market.

All participants who spoke of athletic training in this way had preconceived notions to use their undergraduate educations in athletic training as a background to pursue future goals in another field of health care.

DISCUSSION

Using a socialization theoretical framework, we examined how senior ATSs arrive at postgraduate decisions to help educators provide the best mentorship possible and help the ATS matriculate into the workforce. Our results indicated that for this group of senior ATSs, the first step in the career decision-making process centered on the choice to stay in or leave athletic training. Participants who decided to persist in athletic training did so because of faculty and clinical instructor support, improved marketability, and professional growth. Senior ATSs who elected to leave the profession of athletic training did so because of a shift of interest away from athletic training, lack of respect for the athletic training profession, compensation, time commitment, and use of athletic training as a stepping stone to another career.

Persist in Athletic Training

Professional Growth and Marketability

After the decision was made to enter athletic training, many participants identified a need to develop their clinical skills and marketability through additional training to secure future full-time positions within athletic training. Moreover, several participants discussed the need to continue their maturation as a clinician before assuming the role of a full-time athletic trainer. Marketability and professional growth, as described within this study, are characterized under the universal term of professional socialization. As defined in the literature, professional socialization is a complex learning process designed to prepare and give insight into how individuals understand and fulfill their professional responsibilities.17,35 Through this process, individuals obtain the knowledge, skills, norms, values, roles, and attitudes pertaining to their profession as they are given a realistic view into the profession through structured clinical education experiences.16–19,26 Professional socialization can be an informal orientation where students begin to mature in professional values and identity.7,16,19,26 Our results indicated professional growth and marketability were a means to gain real-world work experience in a more formalized, mentorship experience as a graduate assistant athletic trainer while continuing to advance their educations. This finding is consistent with findings of researchers who recently examined the decision to pursue a postprofessional athletic training program and found the desire to have increased autonomy while receiving mentorship and gaining more advanced knowledge was a priority.23

According to the literature, anticipatory socialization involves formal educational programs or professional preparation,7,19,20,27,35,36 whereas organizational socialization occurs when individuals enter into their respective workforces19,20 and interpret and assume the role of a competent professional.27,35 Our results demonstrated that by deciding to pursue athletic training, students often chose a route of graduate school with an associated athletic training graduate assistantship. The graduate assistantship was pursued because students wanted to be introduced into the real-world job setting but still be able to rely on other individuals and mentors for help. Klossner27 explored how ATSs develop professionally throughout their educational experiences. Klossner's27 results revealed that legitimation, which was described as looking to others for acceptance or reinforcement, begins the process of professional socialization for ATSs.27 Even during the organizational socialization process, Klossner27 described new athletic trainers contacting fellow athletic trainers to learn how to adjust to their new roles and responsibilities. Mensch et al20 described organizational socialization as individuals' adjustment of the ideals and theories they have learned in their professional socialization to the demands and imperfections of the real world. Professional socialization is a fairly complex, very individualistic, specific setting and an ongoing process with multiple dimensions affecting each individual attempting to find his or her place in the work world.35 The professional growth and marketability themes in our study displayed how students address this complex process.

Faculty and Clinical Instructor Support

Anticipatory socialization is a tacit process for the future athletic trainer because it is essential for professional development and for forming an understanding of the roles and responsibilities of the athletic trainer.6,7,19,26,27 Participants who decided to pursue athletic training beyond undergraduate studies did so because of their educational experiences. One of the strongest influences was faculty and clinical instructor support, which was a finding consistent with the work of Neibert et al.16 Faculty members and clinical instructors in ATEPs often assume the role of a mentor,16 which is vital for the growth of the young professional, particularly when young professionals are being socialized into their professional roles.16,21 Athletic training students desire supervisors to demonstrate mentoring behaviors.21 Mentoring is a socialization strategy based on fostering an interpersonal relationship and addressing the educational needs of individuals.21 Students face various professional development challenges during the anticipatory stage of socialization because of the complexity of academic, clinical, and professional environments, and they repeatedly look to mentors for assistance.21 The role of the mentor is pivotal in preparing individuals for their future occupational roles, ensuring that they possess the relevant knowledge and skills to practice.36 It involves bringing together theory and practice, maintaining and developing an effective learning environment, providing professional support and guidance, enhancing the quality of patient care, progressing the career, and assisting in socializing students into their occupational roles.36,37

Athletic training students begin to adopt the established perceptions of their mentors16; therefore, when a mentor encourages continued professional development, students are more inclined to follow those recommendations. As Neibert et al16 highlighted, students are strongly influenced either positively or negatively by the perceptions of their mentors, and in this case, many of the senior ATSs wanted a career in athletic training because of a positive influence from a clinical instructor or faculty member they viewed as a mentor. Klossner27 provided in-depth discussion about how ATSs develop professionally throughout their educational experiences. These results revealed that legitimation begins the process of professional socialization for ATSs.27 Klossner27 described 3 factors that contribute works to legitimation, including the role of socializing agents, effect of role performance, and influence of perceived rewards. Building trusting relationships with socializing agents is rewarding and important to student and professional athletic trainer development. Furthermore, senior ATSs who had an optimistic vision of the profession developed this mindset through their educational experiences, which were facilitated through strong mentorship, a previously identified critical socialization tool for a preprofessional student.21 Mentorship received during the undergraduate experience also is linked directly to the decision of the ATSs to attend a postprofessional athletic training program; this is a decision that also has been found to be related to professional growth and career intentions.23 For many of the participants who were persisting, graduate study via an assistantship was the means to gain this mentorship while continuing to mature professionally.

Decision to Leave Athletic Training

Participants who decided to leave athletic training did so after gaining a more realistic picture of the profession through their educational experiences, recognizing it was not the right profession for them. Participants who decided not to enter athletic training had chosen to pursue training and work in another health care or wellness profession. Our participants often spoke of the perceptions of their classmates, which commonly occurred before completion of the athletic training degree program. Our results demonstrated that multiple factors influence the decision to pursue health care professions other than athletic training.

Shift of Interest Away From Athletic Training

As participants evaluated their futures because of their impending graduations, they began to realize that the roles and responsibilities of an athletic trainer were not what they initially anticipated. This realization was recognized after their socialization into the roles and responsibilities of an athletic trainer through their structured academic coursework and clinical experiences. Ultimately, the students recognized athletic training was not in line with their interests or career goals. Students who indicated a shift in interest seemed to be leaving athletic training because they were not fully aware of the professional roles and responsibilities before enrolling in their undergraduate educational programs. Once enrolled in clinical education experiences, the students in this study realized the roles and responsibilities did not match their expectations or preconceived notions about a career in athletic training. This concept is supported by Mensch and Mitchell,24 who found undergraduate students lacked a full appreciation of the profession; the exception in this study was for those students who had been mentored during a high school experience before attending college. Misconceptions of the skills and responsibilities involved in athletic training eventually can lead students to choose other career paths.24

A shifting interest away from athletic training and change in career path, such as pursuing another health care profession, is multifaceted and based on one's subjective warrant. A subjective warrant is an individual's perceptions of the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to perform work in a specific occupation.38 One's subjective warrant is influenced, for example, by significant others (eg, role models), experiences in a professional education program, and social influences.39 Learning more about why students enter athletic training programs24 and having an understanding of the career decisions of ATSs16 are important to the development and progress of athletic training. Such issues have been explored in other medical professions, including occupational therapy,40 physical therapy,41 and medicine.42

Anticipatory socializing experiences can help ATSs become integrated into athletic training.6 In accordance, researchers who have studied retention within ATEPs have suggested that students who left lacked integration or motivation to persist in athletic training education.6 The motives behind a student's choosing and continuing a career in athletic training are not always in line with the specific duties and skills of an athletic trainer.6,16,24 To ensure retention within the educational program and the profession, students must be educated about the profession before they commit to entering an athletic training program. The motives for entering athletic training should be aligned with the mission of the profession and should not be aligned with a contingency for other career choices.24 The interaction of ATSs with their clinical instructors also can explain reasons for leaving athletic training. Certain clinical instructors might model behavior that is perceived by the ATS as exhibiting imbalance between their professional and personal lives, and ATSs can interpret that lifestyle as the reality of the profession as a whole.16 To help eliminate this problem, clinical instructor training should cover appropriate professional behaviors to demonstrate when around ATSs. The reinforcement of a positive attitude in the workplace potentially can keep young ATSs more interested in the profession. Investigators have discovered that ATSs look to clinical instructors for mentorship and demonstration of positive behaviors toward athletic training.21 If clinical instructors provide a positive mentorship experience, they can provide a better understanding to their ATSs of the roles and responsibilities of an athletic trainer and potentially can lead them to become and remain athletic trainers.

Athletic training has an assortment of attractors, and some include working with athletes, staying associated with sports, becoming a health care provider, and being a part of a team.7 Directly after high school, students often can have a distorted vision of an athletic trainer. They might not have had an athletic trainer at their schools every day, or they might only have seen the athletic trainer taping or making ice bags. Students might choose to enter athletic training because they were athletes in high school and wanted to stay involved in athletics but might not fully understand the role of an athletic trainer. This misunderstanding or underappreciation could lead students to leave athletic training after they begin their undergraduate educations; this is something that seemed to influence not only our participants, but the classmates of our participants who did not complete their degree programs in athletic training. To help retain ATSs, faculty members need to take steps to integrate young students into the clinical realm and not just the academic aspect of athletic training. Before admission to an athletic training program, students could benefit from observation or shadowing an athletic trainer for a certain number of hours during the semester. In addition, students should be exposed to more than just one clinical setting before applying into an athletic training program to gain a holistic understanding of athletic training. Discussions about issues that might thwart an ATS from continuing in the profession also must take place within the classroom, such as in an introduction to athletic training course. These candid discussions can help reduce the number of ATSs who move through their entire curriculum before making the decision that the profession does not meet their expectations or professional goals.

Lack of Respect for the Athletic Training Profession

Participants expressed the concern that the general public and medical community did not respect athletic training, and this lack of respect led them to opt for other careers, which were perceived to carry more professional prestige. This theme, like shift of interest away from athletic training, can be explained by the limited understanding of the job description for athletic training, especially the roles and responsibilities of an athletic trainer and complete exposure to an athletic trainer as a health care provider. As described, students who were mentored by an athletic trainer at their high schools were more likely to appreciate the role of the athletic trainer; however, less than 50% of all high schools in the United States employ an athletic trainer, limiting the potential interactions available for an individual to learn about the profession. Athletic training is still not well understood by other health care providers and might help to explain the misconceptions and lack of respect given to the profession. Physicians, nurses, physical therapists, and other health care providers have been practicing clinically much longer, and students perceive that they are given more respect than athletic trainers. This concept of respect was reinforced in a study in which researchers explored career decisions of ATSs and found one of the reasons to leave athletic training was the deficiency of respect received by the athletic trainer as a health care provider.16

As athletic training continues to develop, the concept of practicing evidence-based practice (EBP) has begun to emerge.43 By incorporating EBP into the practice of athletic training, the profession can become more credible. Having evidence to support the practices of an athletic trainer can make athletic training more respected. Without documented evidence showing the effectiveness of clinical interventions provided by athletic trainers, the profession will struggle to join the ranks of physicians and other medical professionals.43 Education of health care providers, coaches, athletes, parents, government officials, and others is a key step in the positive evolution of athletic training. Members of the NATA and members of the medical community who work closely with athletic trainers need to educate the general public, including potential ATSs, about the worth and value of athletic training. A superior understanding potentially can lead to more respect for athletic trainers. Educating students before they enter the core of athletic training education can help clarify their perceptions about the respect athletic trainers receive and help to retain these students in the profession.

Compensation

As students begin to enter the workforce after years of education, their primary concerns include salary and benefits. Participants expressed concern that compared with other health care providers, athletic trainers received lower pay for the amount of work and number of hours worked. This is not the first time compensation and salary have been discussed as an issue for students involved in athletic training. Researchers have articulated students' concern about compensation.6,16,24 According to the United States Department of Labor Statistics,44 the average salary for an athletic trainer in 2008 was $39 640. When comparing this salary with salaries in other related health care professions, athletic training was the lowest. In 2008, the average earnings for a physician assistant were $85 710; for a registered nurse, $62 450; for an occupational therapist, $66 780; for a physical therapist, $72 790; and for a physical therapist assistant, $46 780.44 When students are made aware of these salary disparities, they might be influenced away from athletic training; however, if educators can highlight the positive trend in the increase of the salary of the athletic trainer and discuss strategies to help promote job satisfaction and a balanced lifestyle, the ATS might recognize the potential that the profession can offer.

When individuals are unhappy with their financial compensation, it often can lead to job dissatisfaction,45,46 which has been one of the most frequently cited reasons for leaving health care professions.45 Job satisfaction is defined as one's perception toward one's professional responsibilities, and it is a key variable to retaining staff, managing turnover, and preventing individuals from leaving.45 Students might develop this perception of job dissatisfaction from their professors or clinical instructors, especially about monetary compensation and time commitments involved with athletic training. Individuals involved in the development of ATSs need to reinforce positive perceptions of athletic training. Educating students about the roles and responsibilities of an athletic trainer is imperative to help retain students in the profession. One participant pointed out that she is pursuing athletic training because she loves it and not because of the compensation she receives. Plausibly, this mindset was learned and reinforced by positive interactions with clinical instructors who demonstrate excitement and passion for their positions, regardless of the financial reward, because clinical instructors can shape a student's experience.25

Time Commitment

For ATSs who decided to leave athletic training, the substantially large time commitment required of individuals working in athletic training was expressed as a major concern. Other people, most likely coaches, athletes, or administrators, can control an athletic trainer's time. Participants had negative perceptions regarding this lack of control and loss of professional autonomy. The ATSs who had decided to leave athletic training also discussed the influence of the combination of low salary and extensive time commitments required as additional reasons for their decisions to leave the profession. Neibert et al16 reported that participants discussed the number of hours worked per week and uncertain work schedules as reasons not to pursue a career in athletic training.16 In another study, researchers examined the reasons undergraduate students choose a career in athletic training and found that too much time involvement was a barrier to athletic training.24 In some cases, an ATS with limited exposure to the profession before enrollment in an ATEP might not have a full appreciation for the large time commitment, which then can negatively influence retention in the profession.

When examining specific reasons for leaving ATEPs before degree completion, Dodge et al6 discovered students believed athletic training could lead to role strain or burnout in the future. This strain from an intensive time commitment can lead to burnout among ATSs before they even begin a career as an athletic trainer. The thoughts and actual process of dropping out can increase substantially when students experience burnout.11,15 Burnout is a form of distress that can be associated with school, professional, or family responsibilities, and it involves negative attitudes and feelings about work and the inability to manage work-related stress.11,46–49 It can be very personal but often develops when individuals work too hard for too long in high-pressure situations.47 Burnout among professionals potentially could begin in the burnout experienced as a student.15 Health care providers experience burnout most often within the first 5 years of their careers, possibly because of lack of adequate exposure to job stressors, idealization of the job, and self-selected attrition.48,49 In a study by Kania et al,48 athletic trainers reported experiencing low to average levels of burnout. In similar research, Giacobbi49 found that 18% of athletic trainers experience moderate to severe burnout and 32% of athletic trainers experience burnout at some point during their careers. Burnout can be caused by a variety of stresses, especially exhaustive time commitments.

The time demand involved with athletic training also can lead to work-family, or work-life, conflict (WFC). Work-family conflict occurs when individuals experience difficulties managing the demands and responsibilities from their personal lives because of their jobs.50,51 This has important implications in terms of attracting and retaining athletic trainers. In athletic training, WFC has been evident in the reasons provided for leaving the profession and reasons for students not entering the profession after graduation.50,51 In one study, some students discussed leaving athletic training because of the limited time available for their marriages and parenting.6 During their undergraduate educations, students realized how much time was involved with a career in athletic training, and they were compelled to spend time with family more than athletes.6 Mazerolle et al50 reported 68% percent of athletic trainers experienced WFC; they felt consumed by their jobs because of the high volume of hours worked and travel necessary to meet their professional responsibilities.50 Burnout and WFC can be attributed to the large number of hours worked by an athletic trainer, and they play an important role in the attrition of ATSs. It is imperative to understand and recognize substantial time commitments required in athletic training can influence attrition. Providing ATSs with a better understanding of these time commitments might help to retain these individuals in the profession.

Stepping Stone

We found that athletic training education was used as a stepping stone by students with intentions of pursuing a different career in the health care field. Studying athletic training helped participants gain more experience and grow more professionally than other undergraduate majors (ie, biology). Neibert et al16 also discovered some students were using athletic training as preparation for other professional programs. In agreement, Mensch and Mitchell24 reported students found interest in a different career, steering them away from athletic training. Students wanting a more hands-on and in-depth experience before moving onto another health care profession, especially medicine, physician assistant, and physical therapy, could use their athletic training education as a stepping stone to those professions.

Students' perceptions regarding athletic training often are misleading. Athletic training students realized late in their undergraduate educations that the career they chose was not what they expected. Educators, clinical instructors, and practicing athletic trainers need to aid in the early socialization of students. Students who understand the actual roles and responsibilities of an athletic trainer earlier in their educations will be more likely to pursue a career in athletic training.

Practical Implications

We hope this article serves as a catalyst for all athletic trainers to reflect on the influences for the ATS when making postgraduation career decisions. As highlighted throughout this article, anticipatory socialization plays a vital role in the persistence of ATSs into the workforce. We recommend athletic training educators and clinicians, specifically in the secondary school setting, continually articulate the importance of an athletic trainer's role. Students who understand the roles and responsibilities of athletic training earlier in their educations might be inclined to become athletic trainers. When approached by secondary school students, athletic trainers can discuss the 6 domains of athletic training and the dynamic nature of the profession. Clinicians must explain to young students that athletic training is not just about taping ankles and handing out water bottles. If students can begin socialization into athletic training earlier in their educations, they can obtain a better perception of athletic training. In addition, we urge athletic training faculty to include time to discuss professional development and postgraduation plans. This can provide guidance to ATSs and help students to explore the professional options available after completion of their undergraduate education. Some students are unaware of the plethora of options available in athletic training after graduation, such as graduate degree programs, internship opportunities, and fellowship positions. Incorporating a class in which different options for an athletic trainer are examined could allow students to gain an understanding of the areas they would enjoy most. Finally, athletic training is a relatively young profession and, when compared with other medical professions, is continually developing. To benefit both athletic training and the retention of ATSs, athletic trainers, educators, physicians, and others need to teach the entire medical community and general public about athletic training. Through education, people will become aware of the roles and responsibilities of an athletic trainer. The hope is that with this understanding, athletic trainers can be held among the ranks of physicians, physicals therapists, and nurses.

Limitations and Future Research

We explored the influences of students' career decisions after graduation from their undergraduate institutions. First, although recruitment of participants was conducted randomly, many of the participants were in NATA Districts 1, 2, and 3. In the future, researchers should seek information on postgraduation decisions from students representing a greater variety of districts. Second, more women volunteered to participate in this study than men. The NATA membership statistics indicate women compose 60% of NATA members; men, 40%.5 However, future investigators should study the influences of postgraduate decisions based on the sex of the ATS.

Participants continually spoke about the reasons they perceived classmates were leaving their athletic training programs years or semesters before completion and graduation. Although the information gathered was important and helps triangulate the data, it was mere speculation rather than the experiences of the participants in our study. Therefore, future investigators might want to interview students who left athletic training programs before graduation to pursue other academic majors.

Our qualitative study took a different approach from the traditional data collection methods of telephone interviews or in-person focus-group interviews. Recently, the use of Web-based data collection has emerged for qualitative inquiries,30 and despite the advancements with technology and the ease with which today's student uses technology, some of the participants might have been less fluent writers than speakers. With the use of Web-based data-collection procedures, participants also could not obtain feedback, which is the objective of in-person focus groups. Web-based questions might not be clear to participants, and without input from others, providing descriptive answers could be difficult.

Lastly, to our knowledge, we are the first to investigate the thought processes of the ATSs as they transition from anticipatory to organizational socialization. Many researchers have evaluated the processes of socialization as separate entities. They have looked at anticipatory socialization or professional socialization. We were attempting to bridge the gap between them and discover how the theory of socialization plays a role during the transition period between anticipatory and professional socialization. We gained an overall perspective about the postgraduation decisions of ATSs; however, many different avenues are available for ATSs after they have graduated and received certification. Therefore, more research related to this issue is warranted. Future researchers should examine the types of graduate programs that students attend and the types of jobs, whether or not in the athletic training, that students are obtaining.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Joseph Ingreselli, Emily Hall, and Megan Fenton for contributing to pilot testing and validating data-collection methods. We also thank the athletic training students who participated in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Delforge GD, Behnke RS. The history and evolution of athletic training education in the United States. J Athl Train. 1999;34(1):53–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winterstein AP. Athletic Training Student Primer: A Foundation for Success. Thorofare, NJ: SLACK Incorporated; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE) Web site. 2010 http://www.caate.net. Updated September 2009. Accessed February 5, [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt V. Education continues to evolve: post-professional work expands. NATA News. 2006 Jan;:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Athletic Trainers' Association Membership Statistics. 2009 http://www.nata.org/members1/documents/membstats/index.cfm. Updated 2010. Accessed October 15, [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodge TM, Mitchell MF, Mensch JM. Student retention in athletic training education programs. J Athl Train. 2009;44(2):197–207. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardiner-Shires A, Mensch J. Attractors to an athletic training career in the high school setting. J Athl Train. 2009;44(3):286–293. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.3.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabrera AF, Nora A, Castaneda MB. College persistence: structural equations modeling test of integrated model of student retention. J Higher Educ. 1993;64(2):123–129. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tinto V. Dropout from higher education: a theoretical synthesis of recent research. Rev Educ Res. 1975;45(1):89–125. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau LK. Institutional factors affecting student retention. Education. 2003;124(1):126–136. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Power DV, et al. Burnout and serious thoughts of dropping out of medical school: a multi-institutional study. Acad Med. 2010;85(1):94–102. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c46aad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deary IJ, Watson R, Hogston R. A longitudinal cohort study of burnout and attrition in nursing students. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43(1):71–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henry KJ, Van Lunen BL, Udermann B, Onate JA. Curricular satisfaction levels of National Athletic Trainers' Association–accredited postprofessional athletic training graduates. J Athl Train. 2009;44(4):391–399. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.4.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stilger VG, Etzel EF, Lantz CD. Life-stress sources and symptoms of collegiate student athletic trainers over the course of an academic year. J Athl Train. 2001;36(4):401–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riter TS, Kaiser DA, Hopkins T, Pennington TR, Chamberlain R, Eggett D. Presence of burnout in undergraduate athletic training students at one Western US university. Athl Train Educ J. 2008;3(2):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neibert P, Huot C, Sexton P. Career decisions of senior athletic training students and recent graduates of accredited athletic training education programs. Athl Train Educ J. 2010;5(3):101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McPherson BD. Socialization into and through sport involvement. In: Luschen GRF, Sage GH, editors. Handbook of Social Science of Sport. Champaign, IL: Stipes; 1981. pp. 246–273. In. eds. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitney WA. Organizational influences and quality-of-life issues during the professional socialization of certified athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):189–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitney WA, Ilsley P, Rintala J. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Division I context. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mensch J, Crews C, Mitchell M. Competing perspectives during organizational socialization on the role of certified athletic trainers in high school settings. J Athl Train. 2005;40(4):333–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]