Abstract

Context

Female athletic trainers (ATs) experience gender discrimination in the workplace due to stereotypical gender roles, but limited information is available regarding the topic.

Objective

To understand the challenges and obstacles faced by young female ATs working in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I athletics.

Design

Exploratory study using semistructured interviews.

Setting

Division I clinical setting.

Patients or Other Participants

A total of 14 female ATs were included in the study, using both criterion and snowball- sampling techniques. Their mean age was 27 ± 2 years, with 5 ± 2 years of overall clinical experience. Criteria included employment at the Division I clinical setting, being a full-time assistant AT, and at least 3 years of working experience but no more than 9 years to avoid role continuance.

Data Collection and Analysis

Analysis of the interview data followed inductive procedures as outlined by a grounded theory approach. Credibility was established by member checks, multiple-analyst triangulation, and peer review.

Results

Clear communication with both coaches and players about expectations and philosophies regarding medical care, a supportive head AT in terms of clinical competence, and having and serving as a role model were cited as critical tools to alleviate gender bias in the workplace.

Conclusions

The female ATs in this study stressed the importance of being assertive with coaches early in the season with regard to the AT's role on the team. They reasoned that these actions brought forth a greater perception of congruity between their roles as ATs and their gender and age. We suggest that female athletic training students seek mentors in their field while they complete their coursework and practicums. The ATs in the current study indicated that a mentor, regardless of sex, helped them feel empowered to navigate the male-centric terrain of athletic departments by encouraging them to be assertive and not second-guess their decisions.

Key Words: gender discrimination, role congruity, mentors

Key Points

Female athletic trainers often encounter gender discrimination, particularly when working with a male team sport coached by a man.

To reduce and manage such workplace discrimination, female athletic trainers found it helpful to receive strong mentorship, serve as role models, have the support of supervisors, and develop effective communication skills.

Despite the passage of Title VII 47 years ago and Title IX 39 years ago, women still struggle with career development and acceptance in the workplace, particularly in college athletics. Although access has increased for women in college athletics since the passage of Title IX—particularly as student-athletes—the percentages of women holding positions in the coaching and administrative ranks have significantly decreased over time.1 The number of women assuming positions within the athletic training field has increased and will undeniably continue to grow; however, female head athletic trainers (ATs) and female ATs at the collegiate level are still underrepresented at the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I level: only a quarter of the full-time staff ATs are female.1,2 Even though there is near-equal representation of men and women in the athletic training profession, fewer women than men practice in the collegiate setting.2,3 In the head AT position, this gap is even more pronounced. In 2010, the NCAA reported that the percentage of women holding the head AT position at the Division I level was 16.3% for the 2009–2010 school year.4 This is a mere 0.8% increase from the 1995–1996 school year, when the NCAA first collected these demographic data. These data indicate underrepresentation in a leadership position and a “glass ceiling” for female ATs who may want to take on more of an administrative role after serving as assistant and associate ATs.

Barriers to Career Advancement for Female ATs

The extant literature describes several barriers that may prevent female ATs in entry-level positions within the collegiate setting from moving up the leadership ladder and also simply achieving respect and job satisfaction. These barriers include work-family conflict,5 kinship responsibility,6 parenthood,2 and incongruent role perceptions7 in collegiate athletic settings. Despite these barriers, many women have been able to persist in athletic training.2 For the female AT, a major factor influencing retention is the fulfillment of work and life balance. More specifically, a female AT is more likely to remain in a position that allows her to adequately and efficiently assume all her roles, which can include mother, caretaker, spouse, and AT. Current research suggests that working as an AT at the collegiate level is time intensive, limiting the hours away from the job to fulfill other roles and responsibilities. As a result, many women make the decision to find a position that affords more time and flexibility in their work schedules.5,6 Further, role stereotypes are sometimes applied to women working in male-dominated areas of collegiate athletics, which may also serve as a barrier to female ATs. One group8 found that a majority of football players perceived female ATs as more nurturing than male ATs, but the players reported feeling more comfortable being treated by a male AT for general medical conditions. Drummond et al9 reported that male athletes indicated their uneasiness with calling on female ATs for sex-specific injuries, but the male athletes did not perceive the female ATs as less experienced or less competent than the male ATs. These 2 studies and the statistics reported by the National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) and the NCAA suggest that gender bias awaits young female ATs as they enter the collegiate ranks and as they work through their first few years as ATs.

Gender Bias and Discrimination in College Athletics

Although Title IX protection may serve as motivation for female ATs to enter the collegiate ranks, the legislation does not mandate equal work environments for male and female ATs. Discrimination, which has been studied extensively within intercollegiate athletic administrations, has been linked to a reduction in organizational commitment and motivation for career success,10,11 as well as the potential for turnover.12 More specifically, treatment discrimination occurs on the job when particular groups receive fewer rewards, resources, or opportunities than they legitimately deserve on the basis of job criteria.13 This form of discrimination can negatively influence many pertinent work outcomes.13,14 For example, treatment discrimination can affect tangible outcomes, such as the assignments one receives or opportunities for promotion and salary increases, as well as less tangible outcomes, such as how well one integrates into the group or the support received from supervisors.

Sport has traditionally been an area of society that has made access difficult for those who differed from the white, male, heterosexual, able-bodied majority.15 This reality is particularly pronounced at the upper management levels of sport. Again, based on NCAA statistics,4 men dominate leadership positions in collegiate sports. Approximately 90% of the athletic directors at the NCAA Division I level are male. In addition, approximately 70% of the associate and assistant athletic directors are male. This domination at the leadership levels, which includes men holding 84% of head AT positions, has allowed men to set the agenda regarding hiring and work policies.

The job of an AT is structured so that the majority of interaction takes place with the head coaches of sports teams. At the Division I level, men coach both men's and women's teams. However, there are no women coaching baseball, men's basketball, football, men's gymnastics, men's ice hockey, men's lacrosse, men's rowing, men's volleyball, men's water polo, or wrestling.4 Given this, female ATs have the potential to interact with more male coaches than female coaches. In her study of the educational and career experiences of female ATs, Shingles16 noted that female ATs reported both respectful and antagonistic relationships with male coaches. Further, Shingles reported that when relationships were harmonious, it was often because the female AT “stood up for herself,”16 gained some measure of respect, and often assumed a “daughter” role to the older male coaches. This daughter role served to fortify the patriarchy and male hegemony that marks collegiate athletic departments.16

Standpoint Theory

As young female ATs are socialized into the field, it is important to record observations about the barriers they face and their suggestions for eradicating these barriers. Standpoint theory emerged in the 1970s and 1980s as a feminist critical theory to examine the relationships between the production of knowledge and practices of power. Standpoint theory, the framework for this study, posits that the social division of labor serves as an appropriate entry point to study the working conditions of women because this is where social life is being assembled.17 The standpoint perspective assumes that knowledge is socially situated18 and that multiple truths emanate from different sociopolitical situations faced by different social groups. To understand the experiences of these different social groups, it is important to begin an analysis from the standpoint of a particular social group. Further, feminist standpoint theory assumes that people develop different perspectives based on their location or position in society; women have a distinct standpoint, particularly in sport, given that the NCAA statistics have shown they are in the minority in many areas.

Standpoint theory serves as a way to situate and produce knowledge from oppositional environments occupied by oppressed groups.19 The theory emerged as feminist researchers began to question the status quo of patriarchal positivism dominating the research world, with women rarely being allowed to answer questions about nature and social concerns. Standpoint theory has rarely been applied to sport but has been espoused as a mechanism that could be the source of illuminating knowledge claims about the working experiences of women.19

As women continue to assume positions within athletic training, as indicated by the NATA demographic data3 presented earlier, it is important to gain a better understanding of the experiences and perceptions of women as they are socialized into their professional roles. With that in mind, the purpose of our larger study was to use standpoint theory to identify and examine the challenges faced by young female ATs as they begin their professional careers, so that strategies in coping with these challenges can be suggested for future practitioners. We hoped to better understand the gender concerns female ATs must face in the collegiate work setting and how they navigate those concerns. In a separate article20 from the same data set, we presented the topics of power and gender discrimination in detail. Gender discrimination was identified as a problem faced by young female ATs, particularly when working with a male sport coached by a male coach. The participants spoke directly about the origin of gender discrimination within the collegiate setting. The foundation of the gender discrimination experiences for the female AT was born largely from the coaches' control and power over medical care providers serving their teams. Control and power were facilitated through the use of traditional gender stereotypes and supported through the “good ol' boys” network.20 In the current manuscript, we introduce emergent categories that highlight potential strategies female ATs can use to address the challenges that occur as a result of gender prejudice in the workplace. Readers are encouraged to examine both the findings presented elsewhere20 and the current findings to appreciate the holistic picture of gender discrimination at the collegiate level as encountered by the novice female AT.

METHODS

In this exploratory study, we sought to understand female ATs' perceptions and experiences related to their professional socialization into the workplace, with special attention paid to the perceptions of gender bias and strategies used to establish professional relationships in the collegiate setting. A qualitative method was selected for this study because such a method allows the researcher to understand the meaning for participants from the firsthand accounts they give of their lives and experiences.21 We also felt that using a critical qualitative method—which relies on open-ended questioning—could yield insights into how power works22 within collegiate athletics. Furthermore, this method allowed us to capture the standpoint of female ATs, in keeping with the study's theoretical framework.

Participants

A criterion sampling strategy23 was used for participant recruitment. Fourteen female participants participated in the study. All the women worked in Division I clinical settings as full-time assistant ATs and had at least 3 years of work experience but no more than 9 years. A cutoff of 10 years of professional experience ensured that participants were still in a period of role inductance, rather than continuation within their professional careers at the collegiate clinical setting. Additionally, convenience and snowball sampling23 were used to identify participants meeting the aforementioned criteria. The participants had a mean age of 27 ± 2 years and clinical experience of 5 ± 2 years. Volunteers represented 5 NATA districts and a mix of both Football Championship Subdivision and Football Bowl Subdivision universities. The individual demographic data for each participant are presented in the Table.

Table.

Individual Participants' Demographics

| Participant |

Age, y |

Experience, y |

National Collegiate Athletic Association Division |

Sport Assignment |

| Amelia | 25 | 4 | FCS | Baseball, women's volleyball |

| Bella | 27 | 5 | FCS | Baseball, men's soccer |

| Brittany | 29 | 8 | FCS | Women's basketball |

| Calli | 25 | 4 | FCS | Men's golf, lacrosse |

| Casey | 28 | 4 | FCS | Women's softball, volleyball |

| Emma | 29 | 6 | FCS | Women's softball, volleyball |

| Grace | 28 | 5 | FBS | Women's soccer |

| Jessie | 29 | 6 | FCS | Men's basketball |

| Josie | 26 | 4 | FCS | Women's basketball |

| Lindsey | 27 | 6 | FCS | Baseball |

| Lynn | 26 | 5 | FBS | Women's basketball, tennis |

| Payton | 29 | 8 | FCS | Men's lacrosse, soccer |

| Rachel | 25 | 3 | FCS | Women's soccer, tennis |

| Sue | 26 | 5 | FCS | Women's soccer |

Abbreviations: FBS, Football Bowl Subdivision; FCS, Football Championship Subdivision.

Procedures

Individuals who expressed an interest in participating in the study did so by replying to an e-mail inquiry from the lead investigator and were sent a demographic data sheet and informed consent form in a follow-up e-mail. Once both documents were returned, a phone interview was scheduled and conducted. Phone interviews followed a semistructured interview guide. The interview guide was created based upon existing literature, particularly using the work of Harding18,19 and DeVault17 (who espoused standpoint theory as a means to investigate the female perspective), along with the knowledge and expertise of 2 coauthors (Appendix). Before data collection, a female AT who was not included in the study reviewed the guide for clarity and interpretability. The interviews were conducted together by 2 researchers, one with knowledge of the AT profession and the other with research experience using standpoint theory. Having 2 researchers present allowed us to fully capture the depth and richness of the interview and the data generated during the interview. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. The extent of data collection was guided by data saturation,24 which was achieved after 14 interviews. Follow-up interviews were conducted with all participants to clarify the initial findings of the study.

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

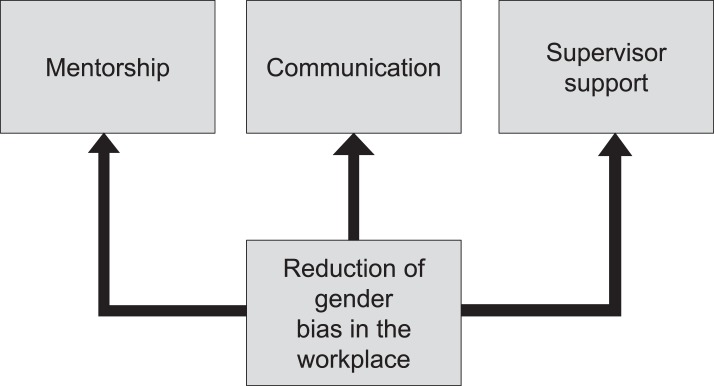

Analysis of the interview data followed open-coding procedures.25 This open-coding process took place in several stages.23,26 First, the 2 researchers independently reviewed the transcribed interviews and took notes in the margins to begin the initial analysis, assigning codes when necessary. These “open codes” were categorized into a system of codes that allowed the researchers to associate interview texts with corresponding themes.27 This enabled the researchers to put together a representation of the professional socialization experiences of young female ATs (Figure). Direct quotes from interview participants were selected for representativeness of each theme and included in the “Results” section.

Figure.

Representation of the professional socialization experiences of young female athletic trainers.

Trustworthiness and credibility regarding interpretation of the data were established through member checks, multiple-analyst triangulation, and peer review.23,24,27 The researchers provided each participant with a copy of her transcribed interview for review and comment. Also, the researchers identified a colleague with knowledge of both qualitative methodology and gender-role stereotyping to serve as a peer reviewer. The role of peer reviewer was to challenge the analysis and coding of the data and attempt to uncover any potential biases in the interpretation of the data.27 In addition, the peer reviewer separately analyzed the data and shared the findings with the researchers, who had also completed independent reviews. After discussing the findings, the researchers and peer reviewer finalized the themes and results generated from the study.

RESULTS

Three categories emerged from the original study regarding ways to negotiate gender discrimination in the workplace. The perceptions of gender bias as experienced by this group of female ATs were presented in a separate paper,20 but it is important to mention that gender concerns exist in collegiate athletics and the current study presents the potential strategies, as identified by this cohort of female ATs, to reduce those experiences. The overall findings as they pertain to the research question, “How do female ATs navigate gender issues in the collegiate work setting?” are illustrated in the Figure.

Strategies to Reduce Gender Bias in the Workplace

Mentorship, clear communication brings credibility, and supportive supervisor and staff materialized from the data to explain ways female ATs have managed instances of gender bias and handled situations in which they felt discriminated against because of their gender. A discussion ensues, with supporting quotes from the data.

Mentorship

Mentorship as discussed by this group of young female ATs was defined as both having a strong role model during the initial socialization into the role of an AT and currently serving as a strong role model for young female ATs in undergraduate degree programs or graduate assistants gaining valuable work experiences. Calli revealed that one of her clinical instructors at her undergraduate institution demonstrated strong professional behaviors:

Hopefully all undergraduates have role models. I know in my undergrad experiences, there is one specific female athletic trainer who, you know, took her job seriously, she got the job done, and she worked with men's lacrosse and they [coaches and players] never questioned her or her judgments. She was very confident in everything she did.

Casey described the mentorship she received during her 2-year graduate assistantship position, especially when dealing with a difficult male coach. She was also able to witness the influence of the female AT on the undergraduate and graduate students she was in contact with on a regular basis:

I absolutely think it was important. My head AT [during grad school] was phenomenal. She was strong and knew her stuff. She would not take any crap from anybody, but at the same time would support you and your growth. She was a phenomenal role model in that sense, and I had so many positive female, full-time athletic trainers during my undergraduate studies. It helped me [having mentors] grow and have the confidence to stand up for myself and handle difficult situations, regardless of whether they [coaches] were male or female.

The sex of the mentor was not a strong influence for the participants. Rather, their mentors demonstrating professional behaviors and supporting the professional development of the student were important factors. Take, for instance, Josie's comments:

It could just be a coincidence that [my mentor] was a female. I mean I was working with baseball [as an undergraduate] with a male mentor, but I had less contact with him. But, I mean, I have had males be just as encouraging.

Grace discussed the importance of both having a mentor and serving as a mentor. When asked what could be done to help reduce workplace gender bias, she candidly revealed the importance of mentorship to professional development of the female:

It starts with the female athletic training students being educated on proper behaviors as well as having them be accountable for their actions. You have to get them to understand that they are going to interact with a lot of student-athletes and certain etiquette is expected of them. I also think having a mentor who can help you out … If you are having issues with a male coach, you can communicate with another person to gain a better perspective.

Many of the female ATs in this study served in the role of a clinical instructor supervising athletic training students in clinical education experiences. They felt they had the opportunity to mentor these young female ATs by modeling professional behaviors, managing the challenges associated with male coaches and male teams, and demonstrating ways to help create a bias-free workplace. Brittany said,

I mentor kids all the time. For instance, one of my graduate assistants was having a difficult time with a coach. He had stepped over the lines. I listened to what she had to say and then I went to bat for her, and that was the right thing to do.

Payton shared this reflection:

I think mentorship is important. It is something that I like to use [with my students]. I have a lot of female athletic training students that work with me, they show more professionalism, so I think it is because I can be a good role model for them. Especially as a female working with a male team. I can show them that you can be respected, you can be professional and do your job without gender playing a role.

Both serving as a mentor and having a mentor appeared to be important agents of socialization to help many of the female ATs manage or alleviate workplace gender bias.

Clear Communication Lends Credibility

Several participants discussed establishing clear communication with coaches and players as to expectations and athletic training philosophies regarding medical care as a critical component to a strong working relationship. When this communication was curtailed, by an administrator, a coach, or the female AT herself, it affected the work environment. Calli felt she was respected by the male coaches she had previously worked with as a result of her communication style: “I think [I am respected] because I am so vocal and confident in my answers.” But Calli observed the negative perceptions that some male coaches had of female ATs and blamed the females for not asserting more confidence:

I feel that certain coaches here view females as being soft or treating their athletes like babies. … These females allow coaches to speak down to them or can be a pushover at times. It shows a lack of self-confidence which can be taken advantage of by people.

Emma discussed the importance of conducting a yearly expectations meeting with the coaching staff before the season begins. In her view, this tactic helps to reduce miscommunication and allows both parties to state expectations and goals. She said,

I think the first thing I do with a new coach [male or female] is sit down with them to say, here is my athletic training philosophy. I think the conversation puts them at ease that I am not really the enemy.

Payton used the same strategy to help increase the respect and rapport between herself and the coaching staff:

I took the first step in the situation. My first day of working with him [the coach], we sat down and had a conversation of expectations with each other and how we wanted to handle certain situations.

Rachel discussed educating the players as to the AT's roles and responsibilities of the AT as well as modeling professional behaviors, which can reduce gender discrimination. She said,

I think you need to maintain a relationship and rapport with your athletes, but maintain that professional line. You know if I happen to see them out to dinner, I would say, “Hi,” but I would not go hang out with them. I do not want to be rude or ignore them, but I want them to know that I don't want to hang out, I am not their friend.

Not all the female ATs were able to communicate successfully because of the culture of the organization. Amelia suggested that her workplace endured micromanagement from senior-level athletic administrators:

There was involvement from the associate athletic director, who had to approve care for the athletes; therefore, the head athletic trainer and the assistant athletic trainers did not control the training room and were not the ones making the decisions on the care provided to the athletes.

Essentially, Amelia is describing a situation in which open communication has been eroded by the actions of 1 administrator, creating a workplace environment that does not embrace open discussion about the proper care for student-athletes.

In some cases, the student-athletes themselves blurred the communication lines between the coach and the AT, threatening to upset the sometimes precarious relationship these two may have. Bella noted:

Every once in a while, there'll be like a little something that comes up. You know, whether it's they [the coaches] feel like one of the players was communicating with me but isn't communicating something to them. And, I mean the way that I really address that is just I, you know, making sure that we don't let the kids like play the coaches off me or me off the coaches. … You know, because otherwise I think what happens is really they [the coaches] feel that the kids are getting like a more sympathetic ear in me and, you know, they're telling me one story, and telling the coaching staff another story.

This perception by the coaches and the student-athletes that the female AT is prone to being more sympathetic—and less pragmatic—further serves to undermine the confidence the coach may have in the AT.

Supervisor Support and Staff

The support of the head AT, or, in some cases, the athletic director, played a significant role for many of these female ATs in managing the challenges associated with gender bias in the workplace. As Payton pointed out, it is the head AT's job to create a positive work culture for all the ATs—male or female: “If someone on staff has a bad experience, the head AT should know about it and help to change the situation into something positive.” Jessie, who described the constant battles she endured with her coaching staff, discussed the importance of having her head AT support her clinical abilities:

I mean he [my head AT] has been very supportive and basically said to them [my coaching staff] that “she is the best person I have on staff right now. She is completely capable of doing her job, and by having a young male or different person in the position, it is not going to alleviate the injuries that you are dealing with.” I mean he has been very supportive, in terms of standing up for me.

Bella, a female AT currently working with 2 male teams, had a similar experience with support from her supervisor. She discussed how her head AT had an initial conversation with the coaches of both teams, regarding her abilities:

When I was first hired, I was working with 2 female teams but was reassigned. It was he [my head AT] who decided to make the change to me covering 2 male sports. So, you know he was not concerned with my professional behaviors or clinical abilities. He has spoken with them as far as just like, “She knows what she is doing. She will take good care of you guys.”

Sue attributed her ability to maintain respect and avoid perceived gender bias in a male-dominated work environment to doing a good job and having the support of her supervisors, particularly her head AT: “You need to have a good enough support system around you, like my boss, I have a male head AT, but he supports me 100% in anything I do.”

Calli also commented on the importance of having a supportive staff around you: “The 2 other full timers that work here, when I'm questioning myself … they're there to support me or give me words of advice, and it really helps.” Bella stressed the significance of being around “people who are all on the same, who have the same goals.”

Although Sue said her head AT—a male—was supportive, she encouraged female ATs to find other women in the athletic department with whom to form professional relationships:

I do have a good working relationship with our SWA [senior woman administrator], so I guess if it was someone else kind of in this position … just try to build a relationship with another female in the administration or within the department.

The female ATs in the study were not always able to find the support they needed from their superiors. Lindsey described a poor experience with a baseball coach who consistently undermined her by seeking out second opinions to “check up” or confirm her initial diagnosis. She discussed how this particular baseball coach would make a point to discuss a male AT at another school, stating “he's been around forever and he really knows what he's doing,” implying that she did not have similar knowledge or skills as an AT. Lindsey said that her head AT was initially supportive of her, but she found out later that he was in fact not supportive:

All the times I thought he was supporting me, he was really going to administration trying to get me fired because he thinks that all the issues I had with my coach were my fault. He thinks that a female shouldn't be working with baseball.

Without the advocacy of the head AT, young female ATs can face an uphill battle to become accepted as competent ATs in male-dominated athletic departments. Mentorship coupled with a supportive staff or head AT can allow these young women the ability to communicate confidently with male coaches and male student-athletes.

DISCUSSION

The impetus for this study was previous research28 investigating work-life balance strategies in the Division I clinical setting. A small group of the female participants identified that, in addition to the challenges of finding a balance between work and life responsibilities, they also struggled to gain respect as female ATs, particularly early in their professional careers. The overall aim of the current paper was to discuss how female ATs navigated those issues, especially gender bias and discrimination,20 which they had recognized as problematic. Data reflecting the issues of gender bias experienced by female ATs were presented in a separate manuscript.20 As identified in other research examining gender stereotyping and discrimination within athletic training,8,29 our findings recognized that female ATs encounter gender discrimination, particularly when working with a male sport coached by a man. As many of the female participants shared their experiences and reflections regarding their initial years of organizational socialization, discussions emerged regarding ways to negotiate discrimination due to their gender. Receiving strong mentorship, serving as a role model, having the support of your supervisor, and developing strong communication skills were revealed as important elements in the female AT's professional development and learning to reduce or manage workplace discrimination due to gender. Further, the findings support the tenets of standpoint theory in that the women offered insights into the intricacies of their work worlds and the social division of labor in collegiate sport (eg, men and women have different experiences). In other words, knowledge resulted from an oppositional environment.19 The female ATs offered their perspectives on one of the by-products of marginalization—discrimination—and how to manage this condition.

Mentorship

Mentoring is one of the cornerstones to facilitating professional growth and development for not only the young professional but also the athletic training student who is learning the various roles, responsibilities, and attitudes of athletic training. For this group of female ATs, it provided the necessary training to help manage the bureaucratic issues that can arise while working in the collegiate settings30 and handle oneself professionally during challenging times. Role modeling, specifically, has been identified as the critical component of the mentorship relationship, as it often allows the student (protégée) to gain a full appreciation of future roles and the expectations associated with those roles.31–33 For this group of female ATs, witnessing ATs managing their responsibilities professionally despite being challenged because of their sex helped them learn how to conduct themselves professionally and acquire the confidence necessary to be respected.

The experiences described by many of the participants echoed those of teachable moments, in which a student witnesses a naturally occurring event that can facilitate learning and reinforce expected behaviors and attitudes.34 This real-time learning is vital to professional development for athletic training students, who often seek authentic educational experiences to facilitate learning, whether in the classroom or clinical education setting.34,35 When supervising female athletic training students, ATs should be cognizant of these teachable moments, especially when they involve professional behaviors and attitudes, because modeling and professional discourse can serve as powerful socializing agents.

Moreover, as demonstrated by the results of this study, the mentor's sex did not mitigate the importance of the mentorship experience; instead, this group valued encouragement, nurturing, modeling, and feedback. These characteristics were identified by other researchers31–33,36 who assessed the mentorship interface within athletic training as helpful in the mentoring process. Furthermore, the sex of the mentor was one of the least important factors for a successful relationship,36 a result consistent with our findings.

Mentorship for this group also meant serving as a strong role model for female athletic training students. The participants discussed the importance of open communication with their students, educating them on the characteristics of professionalism and its importance in the collegiate setting. Pitney et al32 found that effective communication between the clinical instructor and student ranked second only to role modeling in terms of mentoring roles. Communicating expectations for students both in the clinical educational experience and in their future roles as ATs not only helps them to develop stronger communication skills but also reinforces professional discourse among health care providers and members of the sports medicine team. Open communication also allows the protégée to feel invited and welcome to share concerns and questions regarding modeling professional behaviors. An effective communication style has been found to be one of the most valued attributes of a clinical instructor33,36 and ultimately allows the student to gain an appreciation for accepted practices and behaviors. As indicated by one of the participants, “seeing is believing.” If a female athletic training student observes other ATs, male or female, manage their roles as health care providers professionally, then she, too, can display those same attributes.

Clear Communication Lends Credibility

The ability to effectively communicate is a fundamental skill for the AT, who needs to be able to concisely and accurately relay information to a variety of individuals on the sports medicine team. Also critical to an AT's success are people skills, which include the ability to understand and appreciate different points of views and background.37 Many of the female participants capitalized on their communication and people skills to help them navigate professional relationships with their male coaches and athletes. Discourse between the coach and the AT allowed both parties to come to an understanding and agreement on expectations as well as the roles and responsibilities for each member. The female AT's ability to be assertive and proactive in communicating her expectations and philosophies regarding treatment and care demonstrated her confidence in her own clinical abilities and her personal leadership capabilities, which ultimately allowed the male coach to feel confident in her ability to care for his athletes. Thus, his trepidations or stereotypical concerns regarding female ATs were reduced. Interestingly, these behaviors of self-confidence and assertiveness are often stereotypical male attributes rather than female attributes according to social role theory.38 So perhaps the female AT's display of characteristics more familiar to the male coach helped to contradict his negative perceptions of traditional gender-role attributes associated with females, including sensitivity, generosity, and nurturing.38 Moreover, the female AT's demonstration of assertiveness and ambition and encouraging collaboration between herself and the coach are specific behaviors of effective leadership,37 which helps to improve the working environment39 for an employee and, in this case, made a difference in experiences of gender discrimination.

Supportive Supervisor and Staff

Athletic training leaders often use modeling and enabling behaviors to promote a cohesive, unified staff.40 More importantly, head ATs who demonstrate strong leadership skills can improve working conditions for their employees39 and increase overall satisfaction with their current positions.39,41 This was the case for several of the female ATs, who attributed the support received from their supervising AT or head AT as helpful in reducing conflicts or eliminating issues of discrimination completely. Essentially, the head AT is the leader of the sports medicine team, a role that requires him or her to be an advocate for the staff, protect the staff, and nurture and promote professional relationships among all members of the sports medicine team.37 The aforementioned attributes were demonstrated by the head AT's supervising many of the female participants in this study, which facilitated professional relationships between male coaches and female ATs that were free of discrimination. Interestingly, all but 2 of the women who participated in this study were supervised by male head ATs, which could have had an effect on the coaches' willingness to accept endorsements made by the head AT regarding the female AT. Having the supervisor provide support to and actively model confidence in the staff not only is an important leadership quality but is essential for a female AT to receive respect and maintain a professional, collegial relationship with male coaches at the Division I level.

Limitations

Our findings are important in illustrating ways to manage or negotiate gender bias in the workplace; however, certain limitations must be discussed. The inclusion of female ATs at the Division I university setting only restricts the generalizability to other clinical settings. Although the findings as they pertain to strategies can be viewed as universal, only the perspectives of those with Division I experience were included, and these may not accurately describe the workplace environment experienced within the nontraditional or secondary school settings. Furthermore, the female ATs predominately represented the eastern portion of the United States, and none were assigned to football. Athletic training opportunities in football have been dominated by men, and opportunities for women are often limited8,42; female ATs assigned to football teams may have different experiences working with a male sport than the female ATs in our study. Therefore, investigating the experiences of female ATs assigned to football is necessary to increase opportunities for women in this area. Female ATs with less than 10 years of experience were included in the study. This selection criterion was purposeful because many of the participants were living in the moment of the experience. Future investigators may include female ATs who have persisted despite challenges with discrimination. Their insights may help to confirm the findings presented.

The original purpose of our study was to examine the occurrence of gender discrimination within the collegiate setting. Thus, the open-ended, semistructured interview guide was focused primarily on that topic, not on mediating strategies to reduce or manage discrimination. To further explore these strategies and to enhance transferability to other clinical settings, a more focused interview guide should be used.

Recommendations

Future researchers should examine the attitudes and perceptions of head ATs and supervisors of female ATs regarding gender discrimination in the workplace. Supervisor support was critical in the success of these female ATs; as a result, it is important to gain their insights on ways female ATs can be successful within the Division I clinical setting while managing the potential for gender discrimination. Although sex did not mediate the mentorship relationship, having a mentor proved to be a critical learning tool with regard to gender bias and should be investigated further. For a female AT, witnessing a female AT communicating effectively and gaining respect in the workplace may be a more powerful socializing agent than having a male mentor. Previous authors8 have found that football players feel more comfortable, especially with general medical conditions, turning to male ATs and view female ATs as more nurturing; yet the relationship between this opinion and a female AT assigned to football has yet to be assessed. Furthermore, a small percentage of female ATs have succeeded in breaking into the professional sports world. Their achievements can serve as a great learning tool, particularly for future female ATs. Future studies should include a larger sample of female ATs as well as a more diversified sample of employment settings to truly provide a holistic picture of gender discrimination and ways to limit its occurrence. Finally, a standpoint perspective should continue to be used by sport and athletic administration researchers in order to gather viewpoints from marginalized or minority groups. If researchers rely solely on groups with larger representation in the workplace, the analysis will be incomplete.

Appendix. Interview Guide

-

1.

What challenges have you faced in your career thus far?

-

2.

What has contributed to the challenges you've faced early in your career? What are your personal experiences? Can you provide specific examples of challenges that you have faced?

-

a.

Do you think your age contributes to challenges in the athletic training field? If so, how?

-

b.

Do you think your gender contribute to challenges in the athletic training field? If so, how?

-

c.

Possible probes: Is your age a bigger challenge for you? Is your gender a bigger challenge for you? Are they connected?

-

3.

Can you talk about specific challenges you have faced that can be connected to age? To gender?

-

4.

Are there any other identities in addition to being young and female that you might possess that could influence your work experiences and lead to challenges?

-

5.

Can you elaborate on the experiences you've faced when you've been disrespected or felt disrespected? Why do you think it happened?

-

6.

Have your female colleagues experienced similar challenges? Examples?

-

7.

Do you believe you command the same respect as your male colleagues? If so, why? If not, why not?

-

8.

Are your experiences similar working with men's teams compared to women's teams or vice versa? If they are different, can you elaborate on ways in which they are different?

-

9.

Are your experiences similar working with male coaches compared to female coaches? If they are different, can you elaborate on ways in which they are different?

-

10.

What can be done to help female ATs as they enter the workforce to prevent or reduce issues/challenges specific to being a woman in athletic training?

-

11.

What kinds of assistance or support do you think young, female ATs have along the way? How, if at all, does mentoring support you?

-

12.

Is there another area of this topic you would like to discuss?

REFERENCES

- 1.Acosta RV, Carpenter LJ. Women in intercollegiate sport: a longitudinal, national study thirty-one year update (1977–2008) 2011 http://www.womenssportsfoundation.org/binarydata/WSF_ARTICLE/pdf_file. Accessed March 12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahanov L, Loebsack AR, Masucci MA, Roberts J. Perspectives on parenthood and working of female athletic trainers in the secondary school and collegiate settings. J Athl Train. 2010;45(5):459–466. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.5.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Athletic Trainers' Association. 2011 Certified membership. http://www.nata.org/members1/documents/membstats/2011EOY-stats.htm. Accessed May 31. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2009–10 race and gender demographics of NCAA member institutions' personnel report. 2011 http://ncaapublications.com/p-4220-2009-2010-race-and-gender- demographics-member-institutions-report.aspx. Accessed May 28. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ. Work-family conflict, part I: antecedents of work-family conflict among Division I-A athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):513–522. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman A, Mensch JM, Jay M, French KE, Mitchell MF, Fritz SL. Retention and attrition factors for female certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Football Bowl Subdivision setting. J Athl Train. 2010;45(3):287–298. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritter BA, Yoder JD. Gender differences in leader emergence persist even for dominant women: an updated confirmation of role congruity theory. Psych Women Q. 2004;28(3):187–193. [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Connor C, Grappendorf H, Burton L, Harmon SM, Henderson AC, Peel J. National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I football players' perceptions of women in the athletic training room using a role congruity framework. J Athl Train. 2010;45(4):386–391. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.4.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drummond JL, Hostetter K, Laguna P, Gillentinte A, Del Rossi G. Self-reported comfort of collegiate athletes with injury and condition care by same-sex and opposite-sex athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2007;42(1):106–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham GB, Sagas M. Examining potential differences between men and women in the impact of treatment discrimination. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2007;37(12):3010–3024. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham GB, Sagas M, Ashley FB. Coaching self-efficacy, desire to head coach, and occupational turnover intent: gender differences between NCAA assistant coaches of women's teams. Int J Sport Psychol. 2003;34(2):125–137. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aicher T, Sagas M. Sexist beliefs affect perceived treatment discrimination among coaches in Division I intercollegiate athletics. Int J Sport Manage. 2009;10(3):243–262. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenhaus JH, Parasuraman S, Wormley WM. Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance, evaluations, and career outcomes. Acad Manage J. 2009;33(1):64–86. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Button SB. Organizational efforts to affirm sexual diversity: a cross-level examination. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(1):17–28. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fink JS, Pastore DL. Diversity in sport? Utilizing the business literature to devise a comprehensive framework of diversity initiatives. Quest. 1999;51(4):310–327. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shingles RR. Women in Athletic Training: Their Career and Educational Experiences [dissertation] East Lansing: Michigan State University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeVault ML. Liberating Method: Feminism and Social Research. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harding S. Whose Science? Whose Knowledge? Thinking From Women's Lives. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harding S. The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader. New York, NY: Routledge; 2004. Introduction: standpoint theory as a site of political, philosophic, and scientific debate; pp. 1–15. In. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burton LJ, Mazerolle SM, Borland JF. They cannot seem to get past the gender issue: experiences of young female athletic trainers in Division I intercollegiate athletics. Sport Manage Rev. 2012;10:1016–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maxwell JA. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foucault M. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings. New York, NY: Pantheon; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pitney WA, Parker J. Qualitative Research in Physical Activity and the Health Professions. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed. Newbury, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amis J. The art of interviewing for case study research. In: Andrews DL, DS Mason, Silk ML, editors. Qualitative Methods in Sports Studies. Oxford, England: Berg Publishers; 2005. pp. 104–138. In. eds. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazerolle SM, Pitney PA, Casa DJ, Pagnotta KD. Assessing strategies to manage work and life balance of athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):194–205. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walk SR. Moms, sisters, and ladies: women student trainers in men's intercollegiate sport. Men Masculin. 1999;1(3):268–283. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitney WA. Organizational influences and quality-of-life issues during the professional socialization of certified athletic trainers working In the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):189–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitney WA, Ehlers GG. A grounded theory study of the mentoring process involved with undergraduate athletic training students. J Athl Train. 2004;39(4):344–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitney WA, Ehlers GG, Walker S. A descriptive study of athletic training students' perceptions of effective mentoring roles. Internet J Allied Health Sci Pract. 2006;4(2):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curtis N, Helion JG, Domsohn M. Student athletic trainer perceptions of clinical supervisor behaviors: a critical incident study. J Athl Train. 1998;33(3):249–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rich VJ. Clinical instructors' and athletic training students' perceptions of teachable moments in an athletic training clinical education setting. J Athl Train. 2009;44(3):294–303. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.3.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mensch JM, Ennis CD. Pedagogic strategies perceived to enhance student learning in athletic training education. J Athl Train. 2002;37(4 suppl):S199–S207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laurent T, Weidner TG. Clinical instructors' and student athletic trainers' perceptions of helpful clinical instructor characteristics. J Athl Train. 2001;3(1):58–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kutz MR. Leadership and Management in Athletic Training: An Integrated Approach. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2009. p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eagly AH, Karau SJ. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol Rev. 2002;109(3):573–598. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Webster L, Hackett RK. Burnout and leadership in community mental health systems. Adm Policy Ment Health. 1999;26(6):387–399. doi: 10.1023/a:1021382806009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laurent TG, Bradney DA. Leadership behaviors of athletic training leaders compared with leaders in other fields. J Athl Train. 2007;42(1):120–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medley F, Larochelle DR. Transformational leadership and job satisfaction. Nurs Manage. 1995;26(9) doi: 10.1097/00006247-199509000-00017. 64JJ–64LL, 64NN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson MK. Women in athletic training. J Phys Ed Rec Dance. 1992;63(3):42–44. [Google Scholar]