Abstract

Introduction

Through The Global Plan Towards the Elimination of New HIV Infections Among Children by 2015 and Keeping their Mothers Alive, leaders have called for broader action to strengthen the involvement of communities. The Global Plan aspires to reduce new HIV infections among children by 90 percent, and to reduce AIDS-related maternal mortality by half. This article summarizes the results of a review commissioned by UNAIDS to help inform stakeholders on promising practices in community engagement to accelerate progress towards these ambitious goals.

Methods

This research involved extensive literature review and key informant interviews. Community engagement was defined to include participation, mobilization and empowerment while excluding activities that involve communities solely as service recipients. A promising practice was defined as one for which there is documented evidence of its effectiveness in achieving intended results and some indication of replicability, scale up and/or sustainability.

Results

Promising practices that increased the supply of preventing mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services included extending community cadres, strengthening linkages with community- and faith-based organizations and civic participation in programme monitoring. Practices to improve demand for PMTCT included community-led social and behaviour change communication, peer support and participative approaches to generate local solutions. Practices to create an enabling environment included community activism and government leadership for greater involvement of communities.

Committed leadership at all levels, facility, community, district and national, is crucial to success. Genuine community engagement requires a rights-based, capacity-building approach and sustained financial and technical investment. Participative formative research is a first step in building community capacity and helps to ensure programme relevance. Building on existing structures, rather than working in parallel to them, improves programme efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability. Monitoring, innovation and information sharing are critical to scale up.

Conclusions

Ten recommendations on community engagement are offered for ending vertical transmission and enhancing the health of mothers and families: (1) expand the frontline health workforce, (2) increase engagement with community- and faith-based organizations, (3) engage communities in programme monitoring and accountability, (4) promote community-driven social and behaviour change communication including grassroots campaigns and dialogues, (5) expand peer support, (6) empower communities to address programme barriers, (7) support community activism for political commitment, (8) share tools for community engagement, (9) develop better indicators for community involvement and (10) conduct cost analyses of various community engagement strategies. As programmes expand, care should be taken to support and not to undermine work that communities are already doing, but rather to actively identify and build on such efforts.

Keywords: prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, elimination of HIV infections among children and keeping mothers alive, promising practices, community health workers, community-based organizations, community-based monitoring, social and behaviour change communication, greater involvement of people living with HIV, right to health, male engagement

Introduction

In 2010, 390,000 children were newly infected with HIV, of which 90% were in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [1]. However, technology exists to reduce the risk of vertical transmission of HIV from over 30% to less than 2% and has led to the virtual elimination of paediatric HIV in industrialized countries. At the United Nations 2011 High Level Meeting on AIDS, leaders committed to work towards achievement of this goal globally. As outlined in The Global Plan Towards the Elimination of New HIV Infections Among Children by 2015 and Keeping their Mothers Alive, specific targets include a 90% reduction in the number of new HIV infections among children and a 50% reduction in AIDS-related deaths among pregnant women.

The United Nations has developed a comprehensive approach to preventing vertical transmission of HIV, which includes HIV prevention measures and a range of care services for mothers and their children. The approach has four components:

primary prevention of HIV among women of childbearing age;

prevention of unintended pregnancies among women living with HIV;

prevention of HIV transmission from a woman living with HIV to her infant by using anti-retroviral (ARV) prophylaxis or treatment;

provision of appropriate treatment, care and support to women living with HIV and their children and families.

For each component, PMTCT puts into operation the concepts of combination prevention and treatment as prevention for both mothers and children. It also focuses on the health and wellbeing of families. Further, PMTCT incorporates an integrated approach to reproductive health, including the improvement of antenatal, delivery and postnatal care [2,3].

Ending vertical transmission will require women, often living in resource-poor settings, to stay engaged with the healthcare system and face a range of complex and sensitive decisions over an extended period of time. The Global Plan identifies specific community actions as essential to the scale up of PMTCT programmes. It calls on communities to provide services, referrals and linkages, to help plan and monitor programmes, to create demand and to fight stigma and discrimination. In order to inform stakeholders on how to maximize the role of communities, UNAIDS commissioned this desk review to help identify promising practices and document lessons learnt.

Methods

This 2011 study comprised a literature review and key informant interviews. Methods included extensive internet research through selected word searches related to community engagement and PMTCT. Specific stakeholder websites were explored, including those of UNAIDS, the United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), WHO, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and civil society implementing partners. Other sites that provided important leads and resources included the WHO PMTCT Monthly Intelligence Reports; AIDS Support and Technical Assistance Resources (AIDSTAR) HIV Prevention Updates; the University of California at San Francisco's Women, Children and HIV; the Joint Learning Initiative on HIV/AIDS; and the Coalition on Children Affected by AIDS. The types of literature reviewed included journal articles; published and unpublished reports, evaluations and reviews; and abstracts, posters and presentations from international conferences. In proportion with the epidemiology of new HIV infections among children, the focus was largely on SSA, but case studies were identified from other regions as well. The available body of evidence on best practices in community engagement for PMTCT largely comes from grey literature complemented by a small number of controlled or quasi-experimental studies. More than 200 documents were reviewed.

To supplement the literature review, information was collected through e-mail exchanges and telephone and face-to-face interviews (using a semistructured questionnaire) with key informants from organizations supporting community engagement for PMTCT. Informants were identified through the literature review and by key contacts at the global, regional and national level. A total of 35 individuals representing 26 national and international organizations were interviewed. The first draft of the paper was reviewed for technical content by a small group of representatives of civil society, donor and implementing agencies. This article summarizes the review report [4].

Four limitations of the study are noted. First, grassroots initiatives often lack the financial and technical capacity required for programme monitoring, documentation and dissemination. Therefore, available evidence is skewed towards funded activities. Second, PMTCT to date has focused largely on the provision of ARV prophylaxis, and less on the other components of comprehensive services to reduce vertical transmission [2,3]. To augment findings on the other prongs, leads were sought for promising practices in community engagement for HIV prevention, family planning, AIDS care and support as well as maternal, neonatal and child health (MNCH). Third is attributing change. In most cases, community interventions have been undertaken hand-in-hand with facility-based activities and it is difficult to tease out the specific impact of the community component. Lastly, the nature of community work is fluid and context-specific and therefore may be challenging to measure and interpret, especially in terms of its replicability. Despite these constraints, the available body of evidence provided some important promising practices and highlighted gaps that warrant further attention.

Definitions

Community

“Community” is a dynamic concept meaning different things in different contexts and to different people. A landmark study of 94 definitions in 1955 [5] and a subsequent public health analysis [6] provided the basis for the definition used in this review, “a group of people with diverse characteristics who are linked by common ties including shared interests, social interaction and/or geographic location”.

This definition is deliberately inclusive to embrace the wide range of communities involved in ending vertical transmission of HIV, for example current and former PMTCT clients, networks of persons living with HIV, community leaders and opinion makers, as well as local non-governmental organizations.

Community engagement

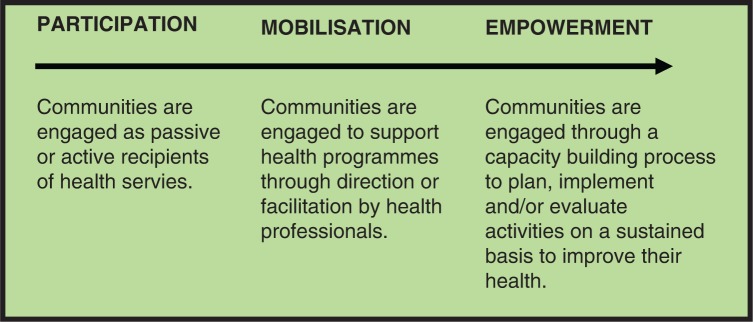

Loosely defined, “community engagement” is the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people with diverse characteristics who are linked by common ties, social interaction and/or geographic location [7]. The spectrum of community engagement in the health sector encompasses the three closely related concepts identified above (Figure 1) [39].

Figure 1.

Spectrum of community engagement.

As shown by the arrow, the literature indicates that over time programmes have moved towards greater community empowerment through a rights-based approach [8,9]. Although practices reflecting all three concepts are currently in use for PMTCT scale up, this review focuses on community mobilization and empowerment. Activities that engage communities solely as passive audiences for information, behaviour change or services have been excluded.

Promising practice

For the purposes of this review, a “promising practice” in community engagement is an approach for which there is documented evidence in at least one setting of its effectiveness in achieving intended health-related results, usually increased PMTCT uptake or compliance. Other important factors taken into consideration are that the practice has been (or shows potential to be) replicated, scaled up and/or sustained.

Results

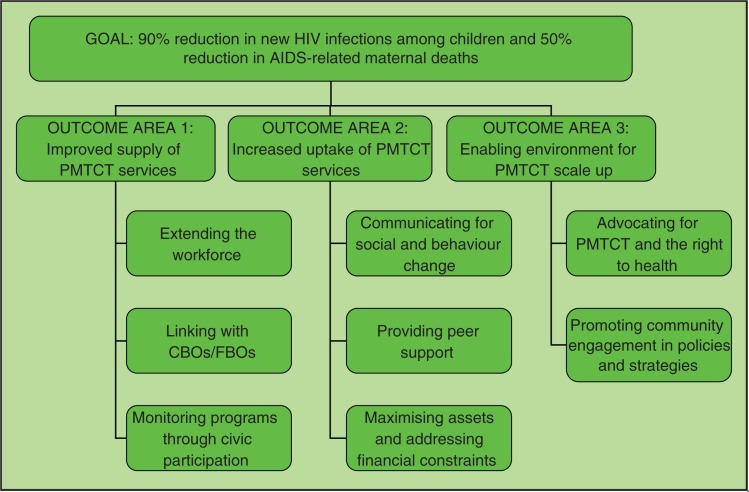

The promising practices identified are organized as shown in Figure 2 according to their primary intended outcome; that is, improved supply of PMTCT services; increased uptake of PMTCT; and, an enabling environment for PMTCT.

Figure 2.

Community engagement practices by intended outcome.

Although this diagram simplifies reality by masking the dynamics and overlap between the three areas,1 it is offered as a conceptual framework for stakeholders as they respond to identified gaps in their PMTCT programmes. Below, the promising practices are described along with examples and a brief summary of lessons learnt. The examples are by no means exhaustive, but are offered to illustrate the practice in operation and some of the results achieved to date.

Outcome area 1: Communities improving the supply of comprehensive PMTCT services

Communities extending the workforce

Across various sectors, community members have been engaged in social development either as volunteers or with remuneration. The benefits of engaging community members as frontline health workers are well documented and include extending the workforce, bringing services closer to people and, benefiting from the intimate knowledge these workers have of their communities. The global community health worker (CHW) Task Force recently called for one million salaried CHWs by 2015, and has issued a report providing cost estimates, a deployment strategy and operational design towards this goal [10].

WHO lists 313 essential tasks for the continuum of HIV prevention, care and treatment and notes that over a third can be performed by frontline health workers [11]. Such workers (including CHWs, mentor mothers and adherence counsellors) have been effectively used for PMTCT scale up in many countries and programmes.

The review finds that:

While there are several ways in which communities serve as health workers, it is useful to anchor them to a primary healthcare system that promotes task sharing.

There is need for functional systems to remunerate and train the workers and provide supportive supervision.

There is need for training to improve service quality, both for lay staff as well as professional health staff.

Frontline health workers operate most effectively when communities have a say in their recruitment.

Linking to community- and faith-based organizations

Organized community responses are key to the HIV response. Community- and faith-based organizations (CBOs/FBOs) are a crucial source of support for millions of families affected by AIDS. They span the horizon of HIV needs including prevention, infant feeding, psychosocial and spiritual support, follow-up and referrals, gender-based inequities, and income generation. They reach remote areas, bringing services closer to vulnerable populations. PMTCT can be integrated effectively into the ongoing work of many CBOs/FBOs, including both facility and community-based services. The flexibility of CBOs/FBOs enables them to support implementation of most of the promising practices found through this review.

Lessons in practice include that:

A first step in developing a community engagement strategy for ending vertical transmission is to understand existing CBO/FBO activities. This can be accomplished through a participative inquiry and mapping exercise [12–14].

CBO/FBO activities should ideally be linked to health facilities with an agreement that spells out how each group operates and how they support one another.

Establishing linkages with CBOs/FBOs that support older children, women and other family members affected by AIDS is essential to ensure continued support after their completion of the PMTCT continuum.

Monitoring PMTCT programmes through civic participation

Poor service quality is a widely acknowledged constraint to PMTCT and other health services. Many supply-side strategies, including clinical mentoring, supervision and the promotion of service standards, are being implemented to improve quality. However, in most resource-poor countries the institutions assigned to monitor public services face significant limitations. There is increasing interest and experience in the role of communities as complementary monitors for health and other public services. A randomized field experiment in Uganda using community report cards and locally developed remedial action plans demonstrated that community monitoring can help to reduce clinic waiting times and absenteeism; improve health facility cleanliness; increase average service utilization and reduce under-five mortality [15]. At a national level, both Rwanda through performance contracts with local authorities [16] and India through the National Rural Health Mission [17] are decentralizing monitoring and accountability.

The findings of the review suggest that:

Broad and continuous stakeholder involvement may promote better appreciation of community demands and lead to greater implementation of agreed reforms.

In order to monitor services, communities need access to timely information, including the evaluation criteria.

Consensus building among health personnel, government authorities and the community around their respective roles and indicators of progress is critical.

More research and evaluation are needed on user-friendly tools to enhance accountability and on the sustainability of community-based monitoring.

Outcome area 2: Increasing the uptake of PMTCT services

Some of the demand-side factors that inhibit PMTCT uptake include inadequate knowledge and misconceptions about HIV, gender inequities, stigma and financial constraints. PMTCT programmes are engaging with communities to address these barriers as follows.

Community-led social and behaviour change communication

The focus of this practice is on engaging communities to plan and implement social and behaviour change communication (SBCC) activities aimed at transforming attitudes to improve PMTCT uptake and promote behaviours that reduce the risk of HIV transmission. Examples include conversations taking place in over 16,000 communities in Ethiopia [38] and Men Taking Action in Zambia,2 a communication strategy that was associated with increased HIV counselling and testing among both PMTCT clients and their partners. Implementers credited the success of the programme to the engagement of culturally revered community leaders [18]. Other programmes are addressing stigma and discrimination. For example, a participatory process undertaken with a rural community in the Eastern Cape of South Africa led to the adoption of a community declaration on HIV which among other actions, resolved “to disclose HIV status with the knowledge that we would have support from our communities” and “not to gossip about or humiliate in any way, those who are known to have HIV/AIDS” [19].

Some of the lessons from community-led SBCC are:

Participatory formative research is essential to ensure that SBCC messages are relevant.

Community members need training and ongoing support to master communication strategies that lead to change.

Communication agents may require some form of compensation to sustain their activities.

Health facilities must be prepared to respond adequately to demand generated through SBCC.

Providing peer support

The engagement of persons living with HIV to provide peer support is widely practised within the global HIV response. Working individually or within a group, peers aim to support women and their families in a variety of ways throughout the PMTCT process. Individual peers, such as the mentors supported in mothers2mothers programmes in nine countries as of mid-2011, recorded improvements in client retention, CD4 testing, prophylaxis uptake, treatment initiation, disclosure and infant testing [20]. In Uganda, Network Support Agents were credited with having mobilized persons living with HIV to utilize services, including both clinic-based and supportive services provided by CBOs [21]. In Botswana, a male-oriented peer education programme was associated in the first year with more than doubling of the number of men who knew their status, quadrupling disclosure rates, and a six-fold increase in the number of men who accompanied partners to ante-natal care (ANC) [22].

In Ethiopia, a review of a mothers’ support group initiative reported that 90% of the mothers and babies enrolled received prophylaxis, compared to a national rate of 53% [23]. However, being based at health centres limited participation for women living far away [24]. A more recent development in PMTCT programmes is the expansion of support groups for other family members, for example mother-in-law support groups in Lesotho or family support groups in Tanzania [25]. An assessment of a couple support group initiative in Uganda found that among group members, communication between partners improved and couples engaged in better birth planning and adherence to ARV prophylaxis increased [26]. Some support groups take on a broader mandate. Many have engaged in income-generating activities to sustain themselves and extend their HIV-related activities in the community. In Mozambique, a health centre-based mothers’ support group initiated in 2008 evolved into a national registered association and expanded its efforts to follow up clients who miss their appointments [27].

Lessons learnt from peer support include:

Peer support has been associated with improved PMTCT service uptake and adherence as well as reduced stigma, including self-stigma and positive living.

When engaging peer counsellors at health facilities, it is important to address any potential stigma from healthcare workers, and to formally incorporate peer counsellors as an integral part of the healthcare team.

There are many different support group models, including both clinic and community based.

Support groups can be empowered to take on a broader mandate in the HIV response self-help and income generation projects.

Maximizing community assets and addressing economic constraints

The Global Plan suggests that communities can facilitate scale up by maximizing local resources in support of PMTCT programmes. For example in rural Nepal, local women were supported to develop and implement strategies to reduce neonatal mortality. ANC visits and facility deliveries increased while neonatal mortality and maternal mortality both declined [28]. In Uganda where transport is a major constraint, local motorcyclists were organized to accept vouchers in exchange for transport to ANC, deliveries and postnatal care. Facility deliveries jumped from less than 200 per month to over 500 [29]. Promising transport initiatives are also being undertaken in South Sudan and Nigeria [30,31].

Lessons learnt include that:

Community engagement is a process that requires a participative approach.

Identifying home-grown solutions and mobilizing local resources helps to guide external funding and ensure sustainability [32].

Outcome area 3: Creating an enabling environment for PMTCT scale up

An enabling environment can be developed from two directions: (a) communities can engage in advocacy to improve policies and actions around PMTCT, and (b) governments and development partners can promote policies that encourage community engagement.

Communities advocating for PMTCT, MNCH and right to health

Community activists have played a key role since the inception of the HIV response. Two examples follow:

Based in South Africa, the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) is a world-renowned coalition that uses a human rights-based framework combining social mobilization and legal action to improve access to treatment. TAC's efforts combine education, HIV treatment literacy and public marches. TAC employed existing legal instruments to seek PMTCT services for women, using the provisions available in South Africa's constitution. This led to the landmark court decision that required the South African government to rollout ARVs for PMTCT at a national scale [33]. In so doing, TAC demonstrated civil society's ability to secure public goods by utilizing the existing enabling environment.

The National Partnership Platform (NPP) works to “create space” for effective dialogue between civil society, governments and other stakeholders. The initiative is active in eastern and southern Africa and comprised of over 55 civil society organizations. In Uganda, the local NPP, in collaboration with two families and other stakeholders, is prosecuting the government over two preventable maternal deaths that occurred in public sector facilities. When court action was delayed, hundreds of advocates took to the streets in protest. The outcome of the trial is still unknown, but the case is bringing high-level attention to the issues of women's health and health as a basic human right [34].

Key lessons from community advocacy include:

Education on human rights, PMTCT, MNCH and local health issues will be needed to empower more communities as advocates and activists.

Financial and technical investment is required to build advocacy skills and coordinate organized activism.

Most-at-risk populations, such as poor rural women, children, injecting drug users, sex workers and others, are in great need for capacity building in advocacy in order to strengthen their voices.

Sustained activism is likely to be required, especially at national and local levels, to ensure the elimination of new HIV infections in children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive.

Promoting policies and strategies that support PMTCT and community engagement

Most major donors, international partners and governments are now promoting community engagement for PMTCT in their technical and funding guidance. In Botswana, the government implemented an intense Total Community Mobilisation that helped to lay the groundwork for its successes today. During this mobilization, about 500,000 community members developed individual action plans, with assistance from trained field officers. An estimated 60% of the people reached reported having complied with their plans [35]. Today, the Government of Botswana cites community mobilization as one of the main strategies for the national PMTCT programme [36]. In Rwanda, a similar programme focuses on male involvement. “Going for Gold” is grounded in high-level political advocacy and intensive community mobilization with local authorities, CHWs and “Male Champions”. Credited in part to this effort, male partner testing has rapidly increased from 16% in 2002/03 to 84% in 2009/10 [16].

These and similar findings reveal that:

High-level political leadership is essential to the successful scale up of community engagement and PMTCT. More effort is needed to generate sufficient political commitment in all countries working on the Global Plan.

Conclusions

Ending new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive is possible, but will not be easy. As reinforced through this review, success will require the sustained engagement and unique inputs of various communities, from small informal groups at the grassroots level right up to global coalitions. The good news is that implementers and experts are conducting many effective community engagement strategies. What remains is to share, strengthen and apply these strategies while rapidly scaling up dedicated resources and community engagement programmes in support of PMTCT, HIV and MNCH. However, as programmes expand, care should be taken to support and not to undermine work that communities are already doing, but rather to actively identify and build on such efforts. The following 10 recommendations are offered to facilitate not only achievement of goals of the Global Plan, but also important broader benefits for women, families and communities.

Expand and support the frontline health workforce for PMTCT scale up: Given the documented benefits of a community workforce for PMTCT and for health more broadly, this review strongly supports the call for 1 million CHWs by 2015.

Increase engagement with CBOs and FBOs: To more fully embrace the potential of existing community organizations in PMTCT scale up, it is recommended that PMTCT implementers identify and more fully collaborate with local CBOs and FBOs; that donors increase technical and financial support for CBOs and FBOs, and that governments support the engagement and capacity development of CBOs and FBOs.

Bring accountability closer to the level of service provision: Emerging evidence indicates that community-based monitoring can increase the uptake and quality of health services, ultimately improving health outcomes. National and local PMTCT programmes are encouraged to pursue mechanisms for community-based monitoring using a rights-based and collaborative approach with community members.

Promote community-driven communication: Issues surrounding ending vertical transmission, HIV, sexual and reproductive health and MNCH, including gender relations, are deeply rooted in culture and community. Communities themselves are best positioned to identify, challenge and transform harmful practices and norms. Governments, implementers and donors should invest in community-led SBCC programmes that empower citizens, especially women living with HIV.

Engage persons living with HIV to provide peer support: Peer support is a key element of many PMTCT programmes. Qualitative evidence suggests that peer support can improve self-esteem, encourage positive living and reduce stigma, including self-stigma. This paper recommends building on peer engagement in locally relevant and sensitive ways to facilitate PMTCT scale up.

Empower communities to maximize their assets and identify their own solutions for PMTCT scale up: Programmes can benefit by supporting community members to identify barriers, mobilize existing resources and create their own local solutions. Factors in the success of this approach include providing communities with the relevant information and opportunities for constructive dialogue as well as adequate seed resources and technical support to mount and sustain their responses.

Support community activism for improved and sustained political commitment: Community advocates have had a role in advancing the HIV response since its inception. They have been an outspoken and effective voice for disenfranchized groups hard hit by the epidemic. Investment in developing local advocacy skills and sustaining strategic activism will be vital to meet the goals of the Global Plan.

Develop and share tools to facilitate decision-making and implementation of locally appropriate community engagement activities: There is an urgent need for concrete tools to assist country teams in planning, implementing and evaluating their community engagement strategies and activities.

Develop better indicators for community engagement: There is a pressing need for better indicators to describe and measure the process and results of PMTCT programmes engaging with communities. There is also need to conduct more evaluation of community engagement practices especially in terms of health outcomes.

Cost analysis: Very little information was found on the costs associated with community engagement. Guidance for donors and implementers would be greatly strengthened by more cost analysis, especially studies that compare the cost effectiveness of different approaches to community engagement.

Acknowledgements

Georgina Caswell, Program Officer, Global Network of People Living with HIVAIDS (GNP +), South Africa; Lucy Ghati, Program Officer, National Empowerment Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS in Kenya (NEPHAK), Kenya; Geoff Foster, Founder, Family AIDS Caring Trust (FACT), Zimbabwe. Robin Gorna, Consultant, Mothers2Mothers, South Africa. Alana Hairston and Damilola Walker, Advisors, Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, USA; Kate Iorpenda, Senior Advisor Children and Impact Mitigation, International HIV/AIDS Alliance, UK; Stuart Kean, Senior Policy Advisor Vulnerable Children and HIV/AIDS, World Vision International, UK; Sally Smith, Partnership Advisor and Robin Jackson, Senior Advisor, UNAIDS, Geneva.

1For example, peer counsellors often contribute to all three outcomes. They can extend the supply of essential services (e.g. adherence counselling), increase the uptake of services (e.g. through follow up) and help to create an enabling environment by modelling positive living.

2The important and well-documented benefits of male involvement in PMTCT and recommended approaches and practices, in the context of women's choices, rights and what works for them, are the focus of a recent review also commissioned by WHO and UNAIDS (Ramirez-Ferrero: WHO [37]).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Gulaid was a consultant contracted for this work; Kiragu is a senior advisor at UNAIDS. This paper was funded by UNAIDS.

Authors' contributions

Kiragu and Gulaid developed the concept, Gulaid conducted the literature review, interviews and prepared the manuscript; both authors revised and finalized the manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

ANC, antenatal care; ARV, anti-retroviral; CBO, Community-based organization; CHW, community health worker; FBO, faith-based organization; MNCH, maternal, neonatal and child health; NPP, National Partnership Platform; PMTCT, prevent mother-to-child transmission (of HIV); SBCC, social and behaviour change communication; SSA, sub-Saharan Africa; TAC, Treatment Action Campaign.

References

- 1.WHO, UNICEF, UNAIDS. Towards universal access; scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector; Geneva: WHO, UNICEF, UNAIDS; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO and UNICEF with the Inter-Agency Task Team. Geneva: WHO; 2007. Guidance on global scale-up of the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: towards universal access for women, infants and young children and eliminating HIV and AIDS among children. [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2011. Joint action for results outcome framework: we can prevent mothers from dying and babies from becoming infected with HIV. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2012. Promising practices in community engagement for the elimination of new HIV infections in children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillery G. Definitions of community: areas of agreement. Soc Forces. 1995;20:111–23. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macqueen KM, McLellan E, Metzger DS, Kegeles S, Strauss RP, Scott R, et al. What is community? An evidence-based definition for participatory public health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):1929–38. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Principles of Community Engagement. (Second Edition): Clinical and Translational Science awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, NIH Publication No. 11-7782, June 2011, accessed 2012 June 23. http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf.

- 8.Rosato M, Laverack G, Grabman LH, Tripaghy P, Nair N, Mwansambo C, et al. Community participation: lessons for maternal, newborn and child health, Alma Ata: rebirth and revision 5. Lancet. 2008;372:962–971. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonard A, Mane P, Rutenberg N. Evidence for the importance of community involvement: implications for initiative to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV; New York: Population Council and ICRW; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Earth Institute of Columbia University, One million CHWs: Technical Task Force Report; New York: Columbia University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. Geneva: WHO Press; 2008. Task shifting: rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams: global recommendations and guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 12.International HIV Alliance: Frontiers Prevention Project. 100 participatory tools to mobilize communities for HIV/AIDS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blackett-Dibinga K, Sussman L. Strengthening the response for children affected by HIV and AIDS through community-based management information systems; Joint Learning Initiative on Children and AIDS (JLICA), 2008 Feb 29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scaling up the response to gender-based violence in PEPFAR: PEPFAR consultation on gender-based violence; Washington, DC: AIDSTAR–1; 2010. May 6–7, [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjorkman M, Svensson J. Power to the people: evidence from a randomized field experiment on community-based monitoring in Uganda; 2008. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper #4268. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mugwaneza P. National experience in male involvement in ANC/PMTCT in Rwanda (PowerPoint); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg S, Laskar AR. Community-based monitoring: key to success of national health programmes. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35(2):214–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.66857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinkala M, Nguni CM, Doherty A, Conley K, Kaliyangile C, Chilufya M, et al. Men Taking Action (MTA): a strategy for male partner involvement in PMTCT services in Zambia (abstract 462 and PPT); 2008. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker W, Birdsall K. HIV/AIDS, Stigma and Faith-based Organisations: a review, Futures Group; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Besser M. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim YM, Lukwago J, Neema S. Final evaluation of the project for expanding the role of networks of people living with HIV/AIDS; New York: Population Council; 2009. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- 22.AED. Trends to watch: male involvement in PMTCT in Botswana, Washington DC [cited 2011 Aug 11]. Available from: http://coach.aed.org/Libraries/Prevention/Male_Involvement_in_PMTCT_in_Botswana.sflb.ashx.

- 23.McLaughlin P, Tessema H, Hagos S. Mother-support-group initiation and scale-up in Ethiopia's PMTCT program [abstract 1219]; 2009. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hope R, Bodasing U. Ethiopia – evaluation of the mothers’ support group strategy. Washington, DC: USAID; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sequeira D'Mello BS, Mbatia R, Andrews L, Chen L, Ramadhani A, Biribonwcha H, et al. Comprehensive PMTCT care and psychosocial support in Tanzania through Family Support Groups [abstract 1500]; 2009. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muwa B, Mugume A, Buzaalirwa L, Nsabagasani X, Kintu P. The role of family support groups in improving male involvement in PMTCT Programmes; 2007. Dec 10–14, [Google Scholar]

- 27.Personal communication. Mozambique: UNICEF; 2011. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- 28.USAID and Access. How to mobilize communities for improved maternal and newborn health; Baltimore, Maryland: JHPIEGO-ACCESS Project; 2009. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Waiswa P, Hafizur Rahman M, Makumbi F, Kiwanuka N, Okui O, et al. Increasing access to institutional deliveries using demand and supply side incentives: early results from a quasi-experimental study. Int Health Hum Rights. 2011;11(Suppl 1):S11. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-11-S1-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.International HIV/AIDS Alliance (key informant interview) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silva AL. London UK: Transaid; 2011. Maternal health and transport: implementing an emergency transport scheme in northern Nigeria. http://www.afcap.org/Documents/Maternal%20health%20and%20transport%20-20implementing%20an%20emergency%20transport%20scheme%20in%20Northerm%20Nigeria.pdfb. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amoaten S. Supporting aid effective responses to children affected by AIDS: lessons learnt on channelling resources to community based organisations. New York: United Nations Children's Fund and World Vision; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heywood M. South Africa's treatment action campaign: combining law and social mobilization to realize the right to health. Journal of Human Rights Practice. 2009;1(1):14–36. [Google Scholar]

- 34.International HIV/AIDS Alliance (key informant interview) 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Humana people to people movement. Botswana: Total Control of the Epidemic (TCE); [cited 2012 Mar 12]. Available from: http://www.humana.org/TCE-Countries/tce-in-botswana. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Department of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care, Government of Botswana. Prevention of mother to child transmission. [cited 2012 Mar 12]. Available from: http://www.hiv.gov.bw/prevention_of_mother2child_transmission.php.

- 37.World Health Organization. Male involvement in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV; Geneva: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Federal HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office (HAPCO) The Multisectoral HIV/AIDS Response Annual Monitoring & Evaluation Report; 2003 EFY (July 2010–June 2011). Addis Ababa, HAPCO, July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rifkin SB. Lessons from community participation in health programmes: a review of the post Alma-Ata experience. International Health. 2009;1(1):31–6. doi: 10.1016/j.inhe.2009.02.001. accessed 2012 June 24. http://www.internationalhealthjournal.com/article/S1876-3413(09)00002-3/fulltext. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]