Abstract

Objectives

By using the Global Fund as a case example, we aim to critically evaluate the evidence generated from 2002 to 2009 for potential negative health system effects of Global Health Initiatives (GHI).

Design

Systematic review of research literature.

Setting

Developing Countries.

Participants

All interventions potentially affecting health systems that were funded by the Global Fund.

Main outcome measures

Negative health system effects of Global Fund investments as reported by study authors.

Results

We identified 24 studies commenting on adverse effects on health systems arising from Global Fund investments. Sixteen were quantitative studies, six were qualitative and two used both quantitative and qualitative methods, but none explicitly stated that the studies were originally designed to capture or to assess health system effects (positive or negative). Only seemingly anecdotal evidence or authors’ perceptions/interpretations of circumstances could be extracted from the included studies.

Conclusions

This study shows that much of the currently available evidence generated between 2002 and 2009 on GHIs potential negative health system effects is not of the quality expected or needed to best serve the academic or broader community. The majority of the reviewed research did not fulfil the requirements of rigorous scientific evidence.

Background

The factors that have undermined and eroded health system performance in many low- and middle-income countries have been debated extensively ever since the emergence of the major Global Health Initiatives (GHI),1–4 with the assertion that they undermine the performance of already weak national health systems by bypassing them.5–8 It has been argued, however, that this criticism would be mainly based on pre-existing assumptions, impressions and beliefs about health systems in developing countries, stakeholder interviews, descriptive cross-sectional case studies, and commentaries and opinion pieces.5,9,10

The purpose of this systematic review is to collate and critically evaluate the available scientific evidence on the negative health system effects of GHIs. We focus on negative health system effects because these have been a source of criticism for GHIs and if true, have important implications for policy-makers. We will use the Global Fund as a case example, because it is currently one of the largest international financing institutions supporting disease-specific programmes in low- and middle-income countries.11,12 These results are expected to apply, to a large extent, to other GHIs as well, because we do not have any reason to believe that the research assessing the Global Fund would be, in general, systematically different in quality than the research conducted on the other GHIs.

This review aims to add to the current debate presented in recent comprehensive reviews,5,9 by critically assessing various aspects of methodological quality affecting the interpretation and application of the evidence base generated by current research, and which were not covered in detail in earlier reviews. We assess the evidence and how the evidence is presented, as uncritical repetition of anecdotal evidence carries the risk of generating a ‘socially constructed reality’, where unsubstantiated claims and perceptions of health system effects could eventually be accepted as a valid representation of the objective reality.13,14 Therefore, to understand the arguments and concerns expressed by the stakeholders and other actors in the field, we explore the current discourses and bring them under critical evaluation.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

All interventions were required to be funded by the Global Fund, and the interventions had to be related to at least one of the six health systems building blocks as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO): service delivery; health workforce; health information; medical products, vaccines and technologies; financing; and leadership and governance.15 We did not set specific criteria for study designs or methods of data analysis. We used the following inclusion criteria when assessing studies for eligibility: papers must clearly state the Global Fund's involvement; relate results to health systems; be published in peer-reviewed scientific journals and use original data, either in the form of primary data or secondary data used as a basis for new analysis.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We identified relevant original studies using a comprehensive list of electronic bibliographic databases, with a highly sensitive search strategy and without language restrictions, to avoid both selection bias of published articles and language bias of publications. We limited our search to peer-reviewed academic journals and studies published between 2002 (coinciding with the founding of the Global Fund) and 2009 to capture the evidence generated during the early years of Global Fund-financed interventions. For MEDLINE/Ovid SP we used the following search syntax ‘global fund.af. OR gfatm.af.’ to identify all studies related to the ‘Global Fund’. The search syntax for other databases is available upon request. The list of electronic databases searched in August 2009 is provided in Appendix A. We identified additional relevant literature by searching the reference lists of included studies and other reviews. Documents available at the Global Fund website were also searched to identify studies meeting the eligibility criteria. ISI Web of Science was searched for articles that cited the studies included in the review.

Data collection

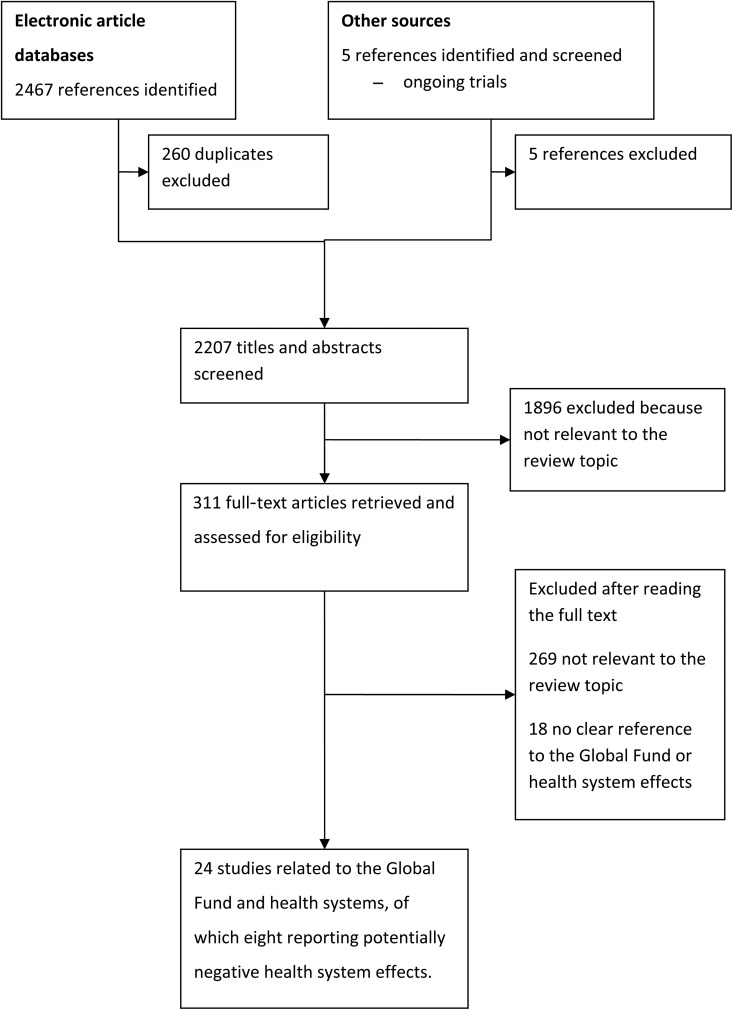

Two review authors (MC, TP) independently screened all references to assess which studies met the inclusion criteria. Any potential disagreements were resolved through discussion between the authors. Figure 1 shows the study selection process. After screening 2207 references, 24 studies were included in this review.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process

None of these studies were explicitly designed to study health system effects, but eight studies reported or commented on perceived negative health system effects. We decided to include all the 24 studies to the review for a more detailed evaluation, because it was clear that the eight studies referred to negative health system effects more by chance than with a predefined purpose in study design. For all the 24 studies we evaluated the generation of evidence base related to the Global Fund in general, and for the eight studies, the generation of evidence base specifically to perceived negative health system effects.

Data extraction and analysis

Two review authors (AK, TP) independently extracted the relevant data from the included studies using standardized data extraction sheets. For data extraction we used an adjusted version of the EPOC data abstraction form.16 We developed a modified checklist for assessing methodological quality of reporting using checklists provided by the EPOC Review Group,17 the STROBE group,18 the Clinical Appraisal Skills Programme19 and Quality Framework,20 adjusted for each study type and design. The template used to assess study quality is provided in Appendix B. Given the lack of generally accepted standards in the appraisal of qualitative research,21,22 and the observed large variability in the methods and quality of reporting, we used the quality assessment framework only for evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of the body of evidence, and not to categorize studies according to predefined thresholds or exclude studies from the analyses.22

Our analysis was based on producing structured summaries and narrative tables, and then contrasting and highlighting similarities, differences and common factors across the studies. The purpose of the analysis was to critically evaluate the processes that generated the study results relating to health system effects and the conclusions presented by the authors. While our approach acknowledges that the requirements and use of evidence in policy-making contexts may have different priorities from clinical decision-making, it underlines the requirement to address the limitations of a given methodology and to acknowledge the appropriate conclusions each study design can optimally support in relation to causality.

Results

Study designs

There were no experimental studies assessing the effects of health system interventions. Of the 24 studies included, 16 were quantitative studies, six were qualitative and two used both quantitative and qualitative methods. Seven of the quantitative studies were descriptive and did not use any explicit statistical methods to analyse their data. The remaining nine quantitative studies used a variety of study designs: one study was an uncontrolled before–after study,23 one uncontrolled study reported data before and during implementation,24 one study utilized time-series data,25 two were cohort studies,26,27 two were cross-sectional studies,28,29 one study used Global Fund grant data for modelling30 and one study modelled economic costs of a national insecticide-treated bed net (ITN) voucher scheme.31 Only one of the six qualitative studies used an explicitly defined qualitative method of analysis.32 The remaining studies did not specify which methods they used.33–37 The two studies using a mix of quantitative and qualitative data were descriptive, without explicit methods of analysis.38,39

Health system components and targeted diseases

One study assessed Global Fund's performance-based funding and was therefore determined to address all health system components, as the Global Fund performance-based funding framework includes assessment of ‘system effects’ of its investments.40 Interventions were most often determined to be related to service delivery (n = 14), medical products, vaccines and technologies (n = 9), and financing (n = 6). Service delivery often overlapped with other health system components. Three studies addressed health workforce-related issues, and three studies also addressed leadership and governance-related issues. None of the included studies explicitly addressed interventions aimed at improving health information systems. Five studies did not target a specific disease, but were addressing wider issues such as countries’ absorptive capacity,30 Global Fund's performance-based funding approach,40 Global Fund-supported programmes’ contribution to international health targets,41 an innovative financing scheme used by the Global Fund (Debt2Health Conversion Scheme)37 or analysing stakeholder opinions and expectations using the Global Fund 360° Stakeholder Survey.29

Interventions

None of the studies explicitly evaluated interventions aimed at strengthening health systems. Twelve studies reported interventions that were originally targeted at individuals. The results for these interventions were reported either at individual level,23,24,26,27,39 national level,25,31,33,42 district level,43 clinic/hospital level44 or at household level.28 Five studies used aggregate data from several countries worldwide, related to overall health systems.29,30,40,41,45 Two studies reported interventions targeted at community levels. Of these, one reported results at clinic level38 and the other at community level.34 The remaining four studies reported national-level interventions.32,35–37,46

Of the 10 studies addressing HIV/AIDS, seven studies were directly related to provision of antiretroviral treatment (ART),23,26,27,33,42,44,45 of which one analysed global prices of antiretroviral drugs.45 Of the five studies relating to malaria, four studies were directly related to distributing ITNs.25,28,31,43 Interventions targeting tuberculosis ranged from national programmes to improving case detection strategies.32,36,39,46 Of the 24 included studies, seven reported at least some data related to health outcomes.23–27,44,46 Of these seven studies, three had a study design that enabled them to study the effect of the target intervention. Two of these were ART efficacy studies from Haiti, and were conducted at the same clinic.26,27 The third was an ART efficacy study conducted in northern Malawi.23

Global fund involvement

Five of the studies used and analysed data directly related to the Global Fund, either because the Global Fund-financed programme collected the data or the data collection was commissioned by the Global Fund.29,30,40,41,45 One study was designed to explore stakeholder experiences with Global Fund's impact at local level.32 The Global Fund was often reported to support national disease programmes, but without clearly specifying the role of funding, recipients of the funding, range of interventions that were implemented using the Global Fund funding and other sources of funding. Overall, Global Fund involvement in the interventions described in the studies was expressed imprecisely and in various different parts of the articles. Some studies reported that Global Fund had financed the study reported.28

Main findings

One study analysed several unfulfilled stakeholder expectations and found that the second largest group of unfulfilled expectations were related to impact.29 These unfulfilled expectations were related to interventions being able to reach target populations, health systems being strengthened through disease-specific approaches and effectiveness of performance-based funding. The authors did not provide explanations as to why they perceived these expectations as unfulfilled, but they found that the more respondents involved with the Global Fund, the fewer unfulfilled expectations stakeholders had. Stakeholders from sub-Saharan Africa were reported to have often unfulfilled expectations.

Table 1 outlines the negative health system effects referred to in the papers and the health system components that these effects relate to. Given the lack of identified studies directly assessing the impact of Global Fund investments on health systems, only seemingly anecdotal evidence or authors’ perceptions/interpretations of circumstances could be extracted from the included studies, which often repeated the commonly expressed concerns over potential negative health system effects of disease-specific programmes. While one of the included studies explicitly noted the lack of reliable evidence on the positive and negative impacts of Global Fund investments on health systems,30 none of the studies assessed the implications of this evidence gap. Studies consistently identified performance-based funding as a factor potentially having negative effects on health systems during all stages of the implementation process. The studies identified the burden placed on countries with the funding application process. Onerous requirements for preparing and presenting grant applications were noted as a disincentive if applicants lacked the capacity to respond and fulfil the criteria set by the Global Fund.34 Concerns were also expressed about sustainability of funding, given the large volumes of external financing and reduced funding of poorly performing grants without due consideration on the impact of the decisions on country programmes and the epidemics.35

Table 1.

Description of studies reporting potentially negative health system effects (n = 8)

| Study | Intervention | Global Fund involvement | Negative health system effects | Health system component |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amin (2007) | National drug policy change | GFATM supported the new malaria drug, and the national policy implementation | Quality and performance issues raised by the GFATM delayed the release of funding. Consequent delay in release of GFATM funds was contributing to a situation where in-service training was not completed in all health facilities. | HW |

| Cassimon (2008) | Debt-to-health swap | Debt2Health as a financing mechanism has been introduced by the GFATM | The recipient government may end up transferring more fiscal resources than intended, e.g. Indonesia had to pay 1 million more Euros than in the absence of debt relief. | F |

| Galarraga (2008) | Unspecified | Analysis of GFATM commissioned 360° Stakeholder Survey data | Stakeholder Survey data showed that resource mobilization and impact indicators were the outcome variables with the highest unmet expectations from stakeholders. These negative perceptions about Global Fund outputs were said to have a negative impact on securing future funding from donors. | F |

| Hill (2007) | National TB programme | GFATM supported existing TB programmes and a social mobilization initiative to sustain the TB control programme | Some aspects of the programme were seen to be in conflict with broader health sector reforms in Cambodia. For example, TB management was identified as a continuing impediment to the conversion of some district hospitals to health centres, part of the new health coverage plan. | F |

| Ntata (2007) | National ARV programme | GFATM supported free provision of ARV | Provision of free ARVs was felt to have led to inequity in access to drugs by geographical location and socioeconomic status and an inadequate dissemination of information regarding ARVs and ‘first-come, first served’ policy favoured wealthier, literate people living in urban areas. | SD |

| Van Oosterhout (2007) | National ART programme | GFATM supported the ART programme and the founding of a new clinic | It was felt that the rapid increase in demand for free ART services resulted in waiting lists up to six months, and many patients died while waiting to initiate treatment. Increased responsibility and workload for clinicians and nurses threatened to overburden and demotivate staff, and the increased administrative duties resulting from more patient files added further workloads to staff compiling the required quarterly reports for the national ART programme. | HW |

| Plamondon (2008) | National TB programme | GFATM funded the scale up of TB services | The quantitative framework of programme evaluation (e.g. number of health workers trained, number of TB clubs) required by the GFATM was considered to overlook quality of services. | SD |

| Swidler (2009) | Community mobilization and empowerment | GFATM funds have been used for community mobilization programmes | In some cases, donors were not in tune with villagers’ needs and communities found it very difficult to secure funding for projects if they had limited experience in proposal writing; the frequent ‘training’ and workshops may benefit the aspiring elite who use it for networking and per diems, and not the beneficiaries they are planned for. | F |

ART, antiretroviral treatment; ARV, antiretroviral; GFATM, Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; TB, tuberculosis

Health system components are: F, Financing; HI, Health information; HW, Health workforce; L&G, Leadership and governance; MPV&T, Medical products, vaccines and technologies; SD, Service delivery

Frequent reporting was seen as a burdensome ‘donor requirement’, with negative effects on programme implementation.32,34,44 For example in Malawi, after a successful scale up of ART programme, the clerical staff noted the challenges of compiling reliable quarterly reports for donors, including the Global Fund.44

The Global Fund expects grant recipients to adjust programme implementation following assessment of grant performance. However, lack of capacity to adjust programmes during implementation threatens sustainability.34 In Kenya, the Global Fund's concerns over grant performance led to delays in releasing funds,35 which negatively affected programme implementation.

A study which explored stakeholder experiences of Global Fund's local impact, suggested that using solely quantitative performance indicators could ignore significant performance related factors.32 The study used two case studies as examples to highlight the discrepancy between quantitative and qualitative performance indicators. In Nicaragua, the numerical target for training community health workers was exceeded by more than two-fold, but the quality of training and resources provided for the community health workers were considered to be poor. Similarly, the success of establishing ‘Tuberculosis Clubs’ was measured against the number of patients affected by tuberculosis attending these Clubs. This indicator ignored the negative experiences expressed by the participants.

Until recently, the Global Fund Board initially approved funding for a two-year period (Phase 1 of funding). The grant performance is evaluated against agreed targets and a decision is made on the funding for a further three years (Phase 2). One study analysed the potential negative effects of the Global Fund's performance-based funding in countries with low national income or with weak health systems,40 to conclude poor grant performance was not related to low country income, weak health systems, state fragility or limited human resources for health.

Quality of reporting

Thirteen studies (58%) had considerable inadequacies in reporting the data used in analysis, the methods or both. Of these studies, five had very little or no description of data. Assessing the quality of studies was particularly challenging in studies using qualitative approaches, but also in the descriptive quantitative studies. For example, inadequacies in transparency and documentation led to difficulties in establishing the level of scientific rigour of the included studies. Only two studies clearly indicated measures taken to avoid bias or sources of error.32,35 Four studies indicated a risk of selection bias.27,29,40,45 Overall, the quality of reporting was suboptimal for most included studies.

Discussion

None of the identified studies explicitly stated that the studies were originally designed to capture or to assess health system effects (positive or negative). Only seemingly anecdotal evidence could be extracted from the included studies. Scientifically sound, high-quality research must be conducted before generalizations can be made on the negative (or positive) health system impacts of Global Fund investments.

Methodological considerations

In view of the absence of experimental studies directly assessing health system effects, the strength of our approach was that we were not limited to a particular study design. Our search strategy was sensitive for detecting the ‘Global Fund’ regardless of the actual projects and interventions, but was limited to studies making formal reference to the Global Fund in the published articles. Some potentially relevant studies may not have been identified, if the published articles did not make a reference to the Global Fund. As we were unable to estimate studies that might have been missed due to lack of referencing to the Global Fund, the representativeness of our sample in relation to all interventions remains unknown.

Our search strategy, however, enabled us to identify all studies that explicitly contribute to the debate on the health systems effects of Global Fund financing of disease-targeted programmes in low- and middle-income countries. Given that none of the included studies were explicitly designed to study health system effects and that there are no uniform guidelines for reporting health system effects, some authors of the original papers may have omitted reporting relevant health system effects alongside their results.

The assessment of study eligibility was often complicated because the authors of the identified articles did not use consistent approaches when referring to the Global Fund. For example, the Global Fund was often indicated to support national programmes, but the link between Global Fund-supported national programmes and the interventions described in the study was not always clearly established. In some cases, the reference to the Global Fund could have easily been omitted or replaced with some other donor organization. Some authors referred to the Global Fund financing of the interventions studied in the acknowledgements section, but not in other parts of the article such as in the introduction or methods, with many studies making the connection between the Global Fund, the interventions described in the study and the relevance to health systems in the discussion sections of the studies. Several discussions had to take place at this stage to clarify decisions to reach a transparent agreement between the review authors – a process, which undeniably involved a certain level of subjectivity by the review authors when determining eligibility. Assessment of eligibility was also significantly affected by the generally suboptimal quality of reporting in the screened studies.

Several studies, both quantitative and qualitative, omitted significant parts of describing data and methods that would have facilitated the assessment of eligibility. Given the methodological challenges faced and the certain level of subjectivity involved in assessing eligibility, it is worth considering potential effects of reviewer bias. The field of evidence synthesis addressing complex adaptive systems, such as health systems, is still in its infancy, and therefore reviewers are forced to make subjective decisions. We aimed to control this current methodological shortcoming by transparently describing each step of the review process and stating our rationale for all decisions so that potential sources of bias would be visible to the reader. Furthermore, the purpose of this review was to assess the current evidence base specifically in relation to type and quality of evidence. Our main results and conclusions are therefore related to general principles of scientific quality, and are thus less affected by subjectivity.

Studies addressing health system effects of the Global Fund investments have been published after the literature search of this review was conducted in 2009.47–51 Due to financial resource restrictions, we were not able to extend the analysis to cover years after 2009. Including more recent evidence into this review would undeniably add to the overall picture provided by this review, particularly in relation to observed health system effects, but it would not change the findings and conclusions on the evidence generation during the period studied.

Evidence on negative health system effects

None of the identified studies published between 2002 and 2009 explicitly and rigorously assessed effects of funding by the Global Fund on health systems. The evidence on effects of funding by the Global Fund currently arises from study designs with higher levels of uncertainty in relation to causality and potential sources of bias. Current discourses around GHIs, including the Global Fund, seem to form a significant part in generating the evidence on the potential negative effects of disease-specific programmes. In line with the previous major reviews,5,9 much of the current debate also specifically around the Global Fund was found to be based on anecdotal evidence and assumptions of perceived negative effects of disease-specific programmes in general.

The review shows the considerable gap between the optimal study designs and the actual study methods used to analyse health system effects of Global Fund investments. The use of anecdotal evidence is undeniably important in some situations, for example when drawing attention to potential adverse effects. But the persistent use and generation of anecdotal evidence when evaluating health system impacts is not scientifically justifiable. More importantly, in situations where anecdotal evidence is the only evidence, it should always be accompanied with careful and critical break down and assessment of attribution. This was not found to be the case in the studies we reviewed.

Compared with the evidence-base for effective health interventions, the current evidence-base for effective implementation of inherently complex health system interventions is very weak,8,52,53 requiring high-quality monitoring and evaluation as well as rigorously designed and executed studies to address the evidence gap – given the quantum of investment by the Global Fund which is essentially funded by tax payers of donor countries.

Limited theoretical understanding of models of causality at health system level further handicaps efforts to establish plausible or probable relationships between interventions targeted to individual health system components and system-level impacts. The lack of rigorous scientific evidence, however, complicates the assessment of observed health system impact and restricts conclusions that could be drawn on system level performance from information derived from lower levels (e.g. individual health system building blocks).

A recent comprehensive assessment on Global Fund's health impact (Global Fund 5-year evaluation) showed that evaluating health system effects at country level faces significant methodological challenges and problems, e.g. in terms of data availability and quality.54 Strengthening country health information systems is therefore a prerequisite in improving evidence base through high-quality research.

Conclusions

This study shows that much of the currently available evidence generated between 2002 and 2009 on Global Fund's potentially negative health system effects is not of the quality expected or needed to best serve the academic or broader community. The current evidence used in scientific literature seems to rely on personal views and anecdotal evidence. While this insight into the field is valuable in informing short-term decision-making, it should only serve as an initial step before acquiring more rigorous research.

The weight of the current debate around the GHIs should move away from non-peer reviewed materials, such as organizational reports, commentaries and ‘descriptive’ discussion papers without verifiable data. The lack of methodological standards for reporting health system effects of complex interventions in developing countries is likely to contribute to the subsequent suboptimal level of quality of reporting observed in this review.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interest

RA was Director of Strategy, Performance and Evaluation Cluster between 2008 and 2012 at The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Global Fund had a role in designing the scope of the study, but had no role in the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. RA conceived the study and contributed to the writing of the article by commenting on the drafts of the manuscript and providing additional insight. These comments did not alter the conclusions of the article

Funding

The review received a partial financial contribution from the Global Fund

Ethical approval

Not Applicable

Guarantor

JC

Contributorship

JC designed and coordinated the study. AK, MC and TP collected and analysed the data. JC and TP together drafted the first versions of the manuscript and edited the paper for publication. AM provided methodological assistance and critically reviewed the manuscript. RA conceived the study and contributed to the writing of the article by commenting on the drafts of the manuscript

Acknowledgements

The Department of Primary Care & Public Health at Imperial College London is grateful for support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre scheme and the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research & Care (CLAHRC) scheme. We thank Rebecca Thompson for her assistance in conducting this review

Reviewer

Veena Raleigh

Appendix A

List of electronic databases searched

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA)

British Library of Development Studies (BLDS)

CAB-Direct

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

CINAHL

ClinicalTrials.gov

The Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness

ECONLIT

EMBASE

The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Pare (EPOC) Specialised Register

Education Resources Information centre (ERIC)

The Global Health Library

Healthcare Management Information Consortium (HMIC)

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS)

IDEAS

Inter-Science (Wiley)

The Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp (ITMA) database

JSTOR

MEDLINE/Ovid SP

National Research Register

POPLINE

PsycINFO

Research Papers in Economics (Repec)

ScienceDirect

Sociological Abstracts

Appendix B

Items in the template used for critical appraisal of scientific quality of reporting

Does the title clearly reflect the purpose of the study?

Does the abstract provide all relevant information in correct format and order?

Does the abstract provide the same information as the main body of text, i.e. same facts can be found from the body of text and abstract?

Do the authors provide a scientific rationale for the study?

Do the authors state the importance of the problem that led to the study?

Do the authors explicitly state the general purpose/aims of the study?

Do the authors state the specific objectives of the research?

Do the authors state any hypotheses to be tested?

Do the authors adequately describe the population studied?

Do the authors provide rationale for the selected study design?

Do the authors state how the study participants were identified and approached/contacted?

Do the authors state eligibility criteria?

Do the authors adequately describe the data and main analysis variables, and how they were obtained?

Have the main analysis variables been validated?

Is the unit of analysis described?

Do the authors describe measures taken in order to avoid bias, confounding, and error?

Is a rationale given for the methods of analysis used?

Are the methods of analysis described adequately?

Were the assumptions of the statistical tests explored? For quantitative studies only.

Is the study location, and setting described adequately?

Did the authors use power calculations to determine sample size? For quantitative studies only.

Do the authors adequately describe the instruments used, such as questionnaire items?

Did the authors conduct a pilot study?

Do the authors report any measures taken to ensure completeness of data collection?

Do the authors report how they treated missing information and/or outliers?

Do the authors report any quality control methods used to ensure completeness and accuracy in data entry and management?

Was the study ethically approved by a research ethics body, if the study included human participants?

If the study involved fieldwork, was that adequately described?

Are there any indications of selective reporting?

Is statistical uncertainty clearly indicated (e.g. by P-values, or confidence intervals)? For quantitative studies only.

Do the results address all the stated research questions/hypotheses?

Are tests for confounding clearly indicated? For quantitative studies only.

Do the authors provide tests for interactions? For quantitative studies only.

Do the use of tables, figures and quotations support and clarify the presentation of results?

Is the distribution of any missing data clearly indicated?

Do the authors clearly summarize the main findings?

Do the authors provide interpretations and explanations for the results, including unexpected results, i.e. what factors might explain the observed results?

Do the authors compare and contrast the results with previous relevant studies, including conflicting evidence?

Do the authors discuss how the results could be generalized?

Do the authors discuss alternative or competing explanations?

Do the authors discuss the implications of the results?

Do the authors adequately discuss the limitations of the study?

Do the authors clearly express their conclusions?

Do the authors suggest areas for future research?

Was conflict of interest statement provided by the authors?

Was the researcher position clearly stated, if study involved collecting qualitative data from human participants?

Was the study report clearly written, i.e. reader-friendly, to the point and concise enough?

References

- 1.Unger JP, De Paepe P, Green A A code of best practice for disease control programmes to avoid damaging health care services in developing countries. Int J Health Plann Manage 2003;18(Suppl. 1):S27–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills A Mass campaigns versus general health services: what have we learnt in 40 years about vertical versus horizontal approaches? Bull World Health Organ 2005;83:315–16 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uplekar M, Raviglione MC The ‘vertical-horizontal’ debates: time for the pendulum to rest (in peace)? Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:413–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiffman J Has donor prioritization of HIV/AIDS displaced aid for other health issues? Health Policy Plan 2008;23:95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biesma RG, Burgha R, Harmer A, et al. The effects of global health initiatives on country health systems: a review of the evidence from HIV/AIDS control. Health Policy Plan 2009;24:239–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buse K, Harmer AM Seven habits of highly effective global public-private health partnerships: practise and potential. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:259–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanefeld J, Musheke M What impact do Global Health Initiatives have on human resources for antiretroviral treatment roll-out? A qualitative policy analysis of implementation processes in Zambia. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:8 DOI:10.1186/1478-4491-7-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reich MR, Takemi K G8 and strengthening of health systems: follow-up to the Toyako summit. Lancet 2009;373:508–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samb B, Evans T, Atun R, et al. World Health Organization maximising positive synergies collaborative group: an assessment of interactions between global health initiatives and country health systems. Lancet 2009;373:2137–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu D, Souteyrand Y, Banda MA, Kaufman J, Perriens JH Investment in HIV/AIDS programs: does it help strengthen health systems in developing countries? Global Health 2008;4:8 DOI:10.1186/1744-8603-4-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brugha R, Donoghue M, Starling M, et al. The Global Fund: managing great expectations. Lancet 2004;364:95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feachem R, Sabot O The Global Fund 2001–2006: a review of the evidence. Glob Public Health 2007;2:325–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hafferty FW Physician oversupply as a socially constructed reality. J Health Soc Behav 1986;27:358–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosse D Cultivating Development: An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice (Anthropology, Culture and Society). London: Pluto Press, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO: Everybody's Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO's Framework for Action. World Health Organization, Geneva: 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 16.EPOC, Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group: Data Abstraction Form. See http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-resources-reviewauthors (last accessed 13 August 2012)

- 17.EPOC, Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group: Data Collection Checklist.See http://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/uploads/datacollectionchecklist.pdf (last accessed 13 August 2012)

- 18.STROBE, Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology: STROBE Checklist for Cohort, Case-control, and Cross-sectional Studies (combined). See http://www.strobestatement.org/index.php?eID=tx_nawsecuredl&u=0&file=fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_combined.pdf&t=1287235759&hash=79f2f5d7f14c6ef2e77e555ec27ae3ef (last accessed 13 August 2012)

- 19.CASP, Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: Making Sense of Evidence. 10 Questions to Help You Make Sense of Qualitative Research. Public Health Resources Unit 2006. See http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Doc_Links/S.Reviews%20Appraisal%20Tool.pdf (last accessed 13 August 2012)

- 20.Spencer L, Ritchie J, Lewis J, Dillon L Quality in Qualitative Evaluation: A Framework for Assessing Research Evidence. A Quality Framework, National Centre for Social Research 2003. See http://www.gsr.gov.uk/downloads/evaluating_policy/a_quality_framework.pdf

- 21.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: CRD's Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. University of York; January 2009. See http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf (last accessed 13 August 2012)

- 22.Mays N, Pope C, Popay J Systematically reviewing qualitative and qualtitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Ser Res Policy 2005;10:6–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jahn A, Floyd S, Crampin AC, et al. Population-level effect of HIV on adult mortality and early evidence of reversal after introduction of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. Lancet 2008;371:1603–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Begovac J, Gedike K, Lukas D, Lepej SZ Late presentation to care for HIV infection in Croatia and the effect of interventions during the Croatian Global Fund project. AIDS Behav 2008;12(Suppl. 4):S48–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ceesay SJ, Casals-Pascual C, Erskine J, et al. Changes in malaria indices between 1999 and 2007 in the Gambia: a retrospective analysis. Lancet 2008;372:1545–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Severe P, Leger P, Charles M, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in a thousand patients with AIDS in Haiti. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2325–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.George E, Noel F, Bois G, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1-infected children in Haiti. J Infect Dis 2007;195:1411–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernando SD, Abeyasinghe RR, Galappaththy GN, Gunawardena N, Rajapakse LC Community factors affecting long-lasting impregnated mosquito net use for malaria control in Sri Lanka. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2008;102:1081–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galarraga O, Bertozzi SM Stakeholders’ opinions and expectations of the Global Fund and their potential economic implications. AIDS 2008;22(Suppl. 1):S7–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu C, Michaud C, Khan K, Murray C Absorptive capacity and disbursements by the Global Fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria: analysis of grant implementation. Lancet 2006;368:483–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulligan JA, Yukich J, Hanson K Costs and effects of the Tanzanian national voucher scheme for insecticide-treated nets. Malar J 2008;7:32 DOI:10.1186/1475-2875-7-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plamondon KM, Hanson L, Labonte R, Abonyi S The Global Fund and tuberculosis in Nicaragua: building sustainable capacity? Can J Public Health 2008;99:355–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ntata PR Equity in access to ARV drugs in Malawi. SAHARA J 2007;4:564–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swidler A, Watkins SC ‘Teach a man to fish’: the sustainability doctrine and its social consequences. World Dev 2009;37:1182–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amin AA, Zurovac D, Kangwana BB, et al. The challenges of changing national malaria drug policy to artemisinin-based combinations in Kenya. Malar J 2007;6:72 DOI:10.1186/1475-2875-6-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill PS, Tan Eang M Resistance and renewal: health sector reform and Cambodia's national tuberculosis programme. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:631–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cassimon D, Renard R, Verbeke K Assessing debt-to-health swaps: a case study on the Global Fund Debt2Health Conversion Scheme. Trop Med Int Health 2008;13:1188–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukherjee JS, Eustache FE Community health workers as a cornerstone for integrating HIV and primary healthcare. AIDS Care 2007;19(Suppl. 1):S73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathew TA, Yanov SA, Mazitov R, et al. Integration of alcohol use disorders identification and management in the tuberculosis programme in Tomsk Oblast, Russia. Eur J Public Health 2009;19:16–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Low-Beer D, Afkhami H, Komatsu R, et al. Making performance-based funding work for health. PLoS Med 2007;4:e219 DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Komatsu R, Low-Beer D, Schwartlander B Global Fund-supported programmes’ contribution to international targets and the Millennium Development Goals: an initial analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:805–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Libamba E, Makombe SD, Harries AD, et al. Malawi's contribution to ″3 by 5″: achievements and challenges. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:156–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Animut A, Gebre-Michael T, Medhin G, et al. Assessment of distribution, knowledge and utilization of insecticide treated nets in selected malaria prone areas of Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 2008;22:268–74 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Oosterhout JJ, Kumwenda JK, Hartung T, Mhango B, Zijlstra EE Can the initial success of the Malawi ART scale-up programme be sustained? The example of Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre. AIDS Care 2007;19:1241–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vasan A, Hoos D, Mukherjee JS, et al. The pricing and procurement of antiretroviral drugs: an observational study of data from the Global Fund. Bull World Health Organ 2006;84:393–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soltan V, Henry AK, Crudu V, Zatusevski I Increasing tuberculosis case detection: lessons from the Republic of Moldova. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:71–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Desai M, Rudge JW, Adisasmito W, et al. Critical interactions between Global Fund-supported programmes and health systems: a case study in Indonesia. Health Policy and Planning 2010;25:i43–7 DOI:10.1093/heapol/czq057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mounier-Jack S, Rudge JW, Phetsouvanh R, et al. Critical interactions between Global Fund-supported programmes and health systems: a case study in Lao People's Democratic Republic. Health Policy and Planning 2010;25:i37–42 DOI:10.1093/heapol/czq056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudge JW, Phuanakoonon S, Nema KH, et al. Critical interactions between Global Fund-supported programmes and health systems: a case study in Papua New Guinea. Health Policy and Planning 2010;25:i48–52 DOI:10.1093/heapol/czq058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hanvoravongchai P, Warakamin B, Coker R Critical interactions between Global Fund-supported programmes and health systems: a case study in Thailand. Health Policy and Planning 2010;25:i53–7 DOI:10.1093/heapol/czq059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trägård A, Bahadur Shrestha I System-wide effects of Global Fund investments in Nepal. Health Policy and Planning 2010;25:i58–62 DOI:10.1093/heapol/czq061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Briggs CJ, Garner P Strategies for integrating primary health services in middle- and low-income countries at the point of delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;2:CD003318 DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD003318.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lewin S, Lavis JN, Oxman AD, et al. Supporting the delivery of cost-effective interventions in primary health-care systems in low-income and middle-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. Lancet 2008;372:928–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Global Fund: Final Report, Global Fund five-year evaluation: Study area 3 The Impact of Collective Efforts on the Reduction of the Disease Burden of AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria. Geneva, May 2009. See http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/terg/evaluations/5year/ (last accessed 13 August 2012)