Abstract

Pediatric burns comprise a major mechanism of injury, affecting millions of children worldwide, with causes including scald injury, fire injury, and child abuse. Burn injuries tend to be classified based on the total body surface area involved and the depth of injury. Large burn injuries have multisystemic manifestations, including injuries to all major organ systems, requiring close supportive and therapeutic measures. Management of burn injuries requires intensive medical therapy for multi-organ dysfunction/failure, and aggressive surgical therapy to prevent sepsis and secondary complications. In addition, pain management throughout this period is vital. Specialized burn centers, which care for these patients with multidisciplinary teams, may be the best places to treat children with major thermal injuries. This review highlights the major components of burn care, stressing the pathophysiologic consequences of burn injury, circulatory and respiratory care, surgical management, and pain management of these often critically ill patients.

Keywords: Burns, pediatric, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Burn injury in children continues to be a major epidemiologic problem around the globe. Nearly a fourth of all burn injuries occur in children under the age of 16, of whom the majority are under the age of five.[1] Most burn injuries are minor and do not necessitate hospital admission.[2] A minority of burn injuries are serious and meet criteria for transfer to a burn center; the care of these critically ill children requires a coordinated effort and expertise in the management of the burned patient. The mortality rate following major burns at these highly specialized centers is less than 3%.[3] This provides a team of pediatricians, surgeons, anesthesiologists, intensivists, nurses, respiratory therapists, and other healthcare providers with a unique opportunity to make a multidisciplinary collaborative effort to help some of the most vulnerable patients.

The cause of burn injury varies depending on the age of the child and based on historical clues. Scald injuries tend to be the most common type of thermal injury under the age of 5, accounting for over 65% of the cases, while fire injury tends to occur in older children, accounting for over 56% of the cases.[4] The identification of injury mechanism may provide clues into the other systemic manifestations, for example, the significant component of coexisting inhalational injury after a fire. Finally, child abuse has to be on the differential for any suspicious lesion. A typical injury of this type involves a pattern consistent with a scald injury in a typical “stocking” distribution, although a high index of suspicion needs to be maintained in all mechanisms of burn injury. In children under the age of 2, nearly 20% of cases of burn injury may be reported to state social services for investigation, and a fifth of these reported patients were discharged to foster care.[5]

The goals of initial patient management include preservation of overall homeostasis while appreciating the physiologic challenges that the burn injury poses to the body. Major burn injury not only results in local damage from the inciting injury, but in many cases results in multisystem injury. Initial efforts are focused on resuscitation, maintaining hemodynamic stability, and airway management. Intermediate efforts are focused on managing the multi-organ failure that results from systemic inflammatory mediators that result in diffuse capillary leak and surgical therapy. Finally, efforts shift to issues with chronic wound healing, pain management, restoration of functional capabilities, and rehabilitation.

This review will focus on the classification of burn injury, physiologic effects of the initial burn injury, management of the primary injury, management of the primary systemic manifestations, and pain management for the burn-injured child.

CLASSIFICATION OF BURN INJURY

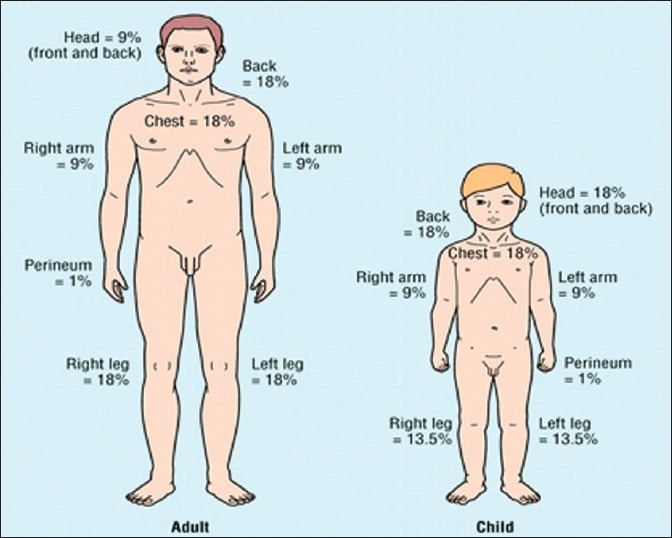

Initial classification of burn injury involves both the depth of the burn and the total body surface area (TBSA) encompassed by the burn injury, which also has implications on the aggressiveness of fluid resuscitation. Figure 1 shows the differences in proportion of TBSA between adults and children.

Figure 1.

Comparative proportions of total body surface area distribution between adults and children

The traditional classification of burns (first, second, third degree) has been replaced by a classification system that reflects the need for surgical therapy-burns are currently grouped as superficial, superficial partial-thickness, deep partial-thickness, full thickness, and fourth-degree burns.[6] A superficial burn is classified as a burn that affects the epidermis, without involvement of the dermis, usually presenting with redness with erythema. A partial thickness burn (both superficial and deep) involves the entire epidermis and variable parts of the dermis. A superficial partial-thickness burn presents with pain, redness that blanches, and blistering. In contrast, a deep partial-thickness burn presents with only pressure, a variable color (white to red) that does not blanch, and blistering-these generally require surgical therapy. Full thickness burns affect the entire epidermis and dermis, usually presenting with a particularly leathery appearance. Lastly, fourth-degree burns are the deepest subgroup with involvement of fascia, muscle, and bones. While deep partial-thickness burns are usually treated with surgical procedures, full thickness and fourth-degree burns are almost always treated with surgical excision and grafting.

SYSTEMIC EFFECTS OF BURN INJURY

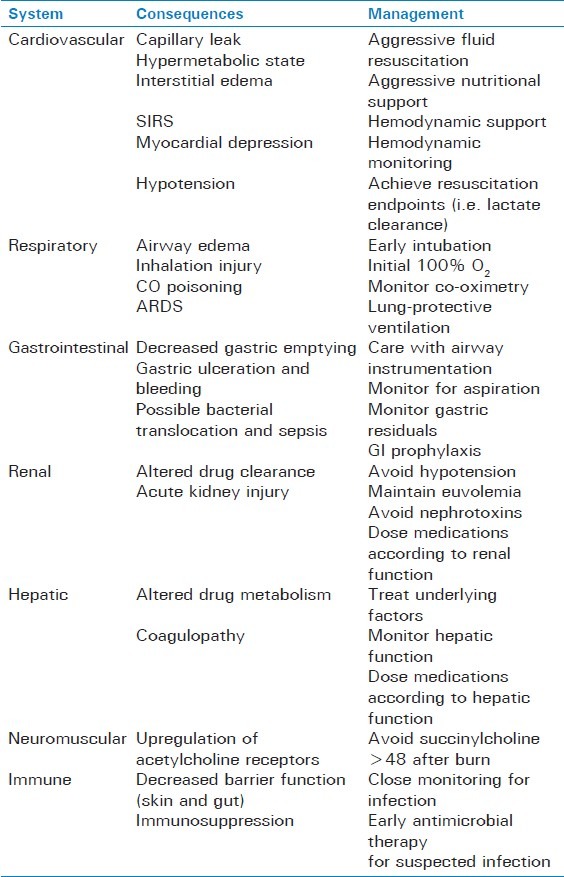

The physiologic manifestations of burn injury span every organ system [Table 1] and can result in profound morbidity and mortality. There is a hormonal and metabolic response to the initial burn injury and, depending on the severity, can cause both local and systemic manifestations. Immediately after the injury is sustained, a variety of vasoactive mediators, catecholamines, and inflammatory markers are released,[7] resulting in a local and systemic capillary leak phenomenon, thus promoting a loss of protein and the development of interstitial edema. This development is a manifestation of the systemic inflammatory release syndrome (SIRS) and carries a high degree of morbidity and mortality.[8] In very large burns (>40% TBSA), significant myocardial depression and hypotension may ensue,[9] thus making hemodynamic management challenging.

Table 1.

Pathophysiologic manifestations of burn injury

In addition to the development of SIRS, a hypermetabolic state ensues as well. The inflammatory mediators and loss of protein result in a significant increase in energy expenditure and a catabolic state,[10] while the level of anabolic hormones is markedly decreased[11] causing an imbalance of energy use and availability. This contributes to a loss of muscle protein, bone mineral density, and overall bone mineral content.[1] In addition, thermoregulatory responses are impaired, with resetting of the patient's core temperature in proportion to the total burn area.[12] Burned skin is unable to retain heat and water, with the potential consequence of massive evaporative fluid losses and metabolic responses much more severe than thought previously.[13]

From a respiratory standpoint, burn injury results in a complicated picture, with initial management focused on securing a potentially edematous airway, and further management involving management of the consequences of inhalational injury, poisoning with carbon monoxide and cyanide, and the management of the potential development of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). It has been demonstrated that both larger burn size and younger age are independent predictors for the need for intubation,[14] and that morbidity and mortality are high in burn patients with respiratory problems or inhalational injury.[15]

Gastrointestinal system dysfunction with bacterial translocation across the gut is a common complication of major burn injury and an independent cause of septic shock in the post-burn patient.[16] Bleeding from acute ulceration of the gastric mucosa may contribute to hypotension, anemia, and possible perforation, peritonitis, and septic shock.[17] Finally, the acute decrease in gastric emptying may put the burn patient at risk for aspiration during periods of sedation, airway instrumentation, or changes in mental status.[18]

Renal and hepatic dysfunction is primarily a result of decreased perfusion secondary to multifactorial causes of hypotension including significant evaporative fluid loss, protein loss, and decreased effective circulating volume, SIRS, and the development of septic shock in the setting of decreased barrier function.[19] Increased levels of catecholamines and inflammatory mediators result in vasoconstriction of the renal vasculature, which can be further aggravated by myoglobinuria, especially in children with electric burns. A secondary effect of hepatic and renal dysfunction is altered metabolism and elimination of several drugs used routinely in the care of the burn patient.

The propensity to develop infectious complications in burn children is secondary to disruption of barrier function of skin and gut mucosa, coupled with the immunosuppressive effects of burn injury. In addition to the wound as an obvious source of infection, other sites which demand vigilance and consideration in the burn patient include bacterial translocation from the gut, intravenous catheter-related bloodstream infection, urinary catheters, and ventilator-associated pneumonia.[20] Fever, tachycardia, and leukocytosis (three classic SIRS symptoms) are almost universal in burn patients and do not necessarily indicate sepsis.

Pharmacologic changes and altered binding and clearance of drugs occur almost immediately after burn injury, altering the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of many drugs. In the initial state of hypotension and organ injury, renal clearance is impaired, while later hyperdynamic and hypermetabolic states (>48 h after burn injury) lead to increased clearance.

Decreased levels of serum albumin, occurring almost immediately, leads to increased free fraction of acidic drugs, while increased levels of a acid glycoprotein results in decreased free fraction of basic drugs.[21] A systemic upregulation of acetylcholine receptors and their proliferation to extra-junctional locations has been noted over time during the acute course of burn illness,[22] making succinylcholine administration to patients >24 h after burn injury an unsafe practice, potentially leading to life-threatening hyperkalemia and cardiac arrest. From a pain management standpoint, the elimination of morphine is unchanged after burn injury.[23]

MANAGEMENT OF INHALATIONAL INJURY AND RESPIRATORY FAILURE

Initial management of the pediatric burn patient requires evaluation of potential airway compromise, oxygenation, and ventilation. Predictors of significant inhalation injury and impending respiratory failure including stridor, wheezing, drooling, and hoarseness are indicative of airway swelling and compromise. The presence of soot in the mouth, facial burns, and history of entrapment in closed spaces such as house fires may be even more useful predictors of significant injury.[24] Circumferential burns to the neck can result in tight eschar formation that can exacerbate upper airway compromise. The key to airway management is to rapidly secure the airway prior to overt airway closure. The advent of fiberoptic intubation, video laryngoscopes, and laryngeal mask airway (LMA)-guided intubation has aided in the management of the difficult airway, although the route of tracheal intubation should be individualized and planned ahead of time.[25]

The source of burn injury to the lung involves a combination of both direct lung injury and systemic toxicity.

Gas phase constituents of smoke including carbon monoxide (CO), cyanide, acidic and aldehyde gases, and oxidants can directly impair ciliary function, increase bronchial vessel permeability, and lead to alveolar destruction. In addition, the release of inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor, and neutrophil infiltration alter microvascular barrier function, leading to the development of pulmonary edema.[26] The direct alveolar injury, along with airway and bronchial edema, sloughing of necrotic epithelial mucosa producing thick secretions, and resultant ventilation−perfusion mismatch, ultimately lead to hypoxia.

The inhaled byproducts of burning wood, plastic, and other materials can lead to carbon monoxide (CO) and cyanide (CN) poisoning. CO has a 250-fold affinity for hemoglobin as compared to oxygen, and shifts the oxy-hemoglobin dissociation curve to the left, ultimately resulting in the impairment of oxygen delivery to tissues. The treatment of CO poisoning relies on administration of 100% oxygen, with hyperbaric oxygen therapy reserved for refractory toxicity, as it is fraught with practical difficulties of transporting critically ill patients into hyperbaric chambers. Cyanide is released when natural and synthetic polymers are burned, and causes tissue hypoxia by uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria. Treatment should be considered for patients with unexplained severe lactic acidosis, despite normal oxygen saturation and low carboxyhemoglobin levels.[27]

Ventilator strategies to manage hypoxia and ARDS in the pediatric burn patient can be challenging. While a lung-protective ventilation strategy using low-tidal volumes, positive end-expiratory pressure, and permissive hypercarbia have clearly shown a benefit in adult patients with ARDS,[28] this strategy seems reasonable in pediatric patients as well, as it minimizes the effect of ventilator-induced lung injury.[29] Refractory hypoxia in pediatric burn patients has been managed by a variety of methods, including the use of high-frequency percussive ventilation (HFPV) and high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV).[30] In addition, small studies have shown a survival benefit to the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in these patients if they have failed maximal ventilator therapy.[31] Despite the progress in using advanced ventilator strategies for managing refractory hypoxia in these patients, there is unfortunately a lack of consensus amongst major burn centers as to which therapy is the best, with wide variability in practice being noted.[32]

FLUID MANAGEMENT

Fluid resuscitation is of paramount importance during the initial care of the burned child. During the initial phase of resuscitation, adequate vascular access must be obtained. While preferable to not use a site that is burned, sometimes very large burn areas preclude this, and observational evidence shows that intravenous catheters may be placed through burned skin.[33] Central venous access may be necessary in select cases and does appear to be safe in children with burn injury.[34] The overall objective of resuscitation is to replace fluid losses and restore euvolemia, while avoiding the detrimental effects of fluid overload.

The fluid requirements may be calculated using several different formulae, all of which achieve good results. The Parkland formula provides a simple and easily remembered basis for resuscitation (4 mL Ringer's lactate (RL)/kg/percent BSA burned; one-half to be given during the first 8 h after injury and the rest in the next 16 h). The type of fluid administered is generally an isotonic crystalloid, with the recommendation for the addition of dextrose to children under 20 kg to prevent the development of hypoglycemia.[35] While some experts have recommended the use of colloid early in resuscitation,[36] large reviews have not demonstrated a survival benefit.[37] The Parkland formula has been observed to underestimate resuscitation volumes in children,[38] especially in the presence of inhalational injury.[39] Thus, it is critical to monitor the endpoints of fluid resuscitation including hemodynamics, urine output-with a goal of maintenance of 1–2 mL/kg/h for children <30 kg and 0.5–1 mL/kg/h for those ≥30 kg,[40] mental status, lactate levels, and base deficit.

BURN WOUND MANAGEMENT

After stabilization of the critical care issues in the burn-injured child, attention is directed toward burn wound management. The key elements of conservative burn wound management include cleansing, debridement, topical antimicrobial agents, and dressing changes of the burned areas. Superficial burns with an intact epidermis do not require specific treatment with antimicrobial agents or dressing changes.[41] For patients with deeper burns, there is no consensus on which combination of topical agents and dressings provides the best wound coverage and infection control.[42]

Cleansing allows better inspection of the wound surface, and debridement removes devitalized and necrotic tissue from the burn wound. Burn wounds are initially gently cleansed mild soap and water, and debridement is performed using gentle mechanical techniques, such as brushing or scraping. In addition, a number of proteolytic enzymes have been used to aid debridement,[43] although they should not be used if infection is suspected. The use of topical antimicrobial agents has reduced the incidence of invasive wound infections,[44] although a specific agent has not been shown to be superior.[42] Lastly, regular dressing changes and aggressive wound care are instrumental toward recovery, as it protects the wound from further infection, provides comfort, and promotes healing, although no trial has been performed to address the optimal frequency of dressing changes. It should be noted that a variety of dressings exist including standard fine mesh gauze, hydrocolloid, silver-containing dressings, biosynthetic, and biologic dressings. While each has particular theoretical advantages,[45] there is no clear evidence on which dressing provides the best coverage; thus, the choice can be made based on cost, availability, frequency of dressing changes (i.e. dressing which minimizes amount of changes may be more suitable for children), and institutional familiarity.

Definitive surgical management of the wound includes excision, grafting, and reconstruction. Burn reconstruction procedures have the ultimate goal of covering wounds, restoring function, and preserving esthetics.[46] In addition, the reconstruction is often completed in separate phases, depending on severity of burn and donor tissue availability. The use of early excision and skin grafting allows initial acute coverage of burns; also, early excision and skin grafting reduce necrotic and infected tissue.[47] In addition, early excision and skin grafting leads to decreased hospital lengths of stay, a reduced cost of hospital care,[48] and a significant reduction in mortality.[49]

Free skin grafts with either full or split thickness are the conventional options for burn wound coverage after excision. Split thickness grafts allow the advantage of covering large surface areas with less donor skin, while full thick grafts allow the advantage of improved skin texture and esthetics.[46] In addition to free skin grafts, a variety of biosynthetic skin substitutes (i.e. Integra, Matriderm) have increased the number of reconstructive options. These biosynthetic substitutes attempt to replicate the properties of normal skin, which is then supplemented with a thin split thickness free skin graft. Unfortunately, data derived from large prospective trials of skin substitutes are currently lacking.

PAIN MANAGEMENT

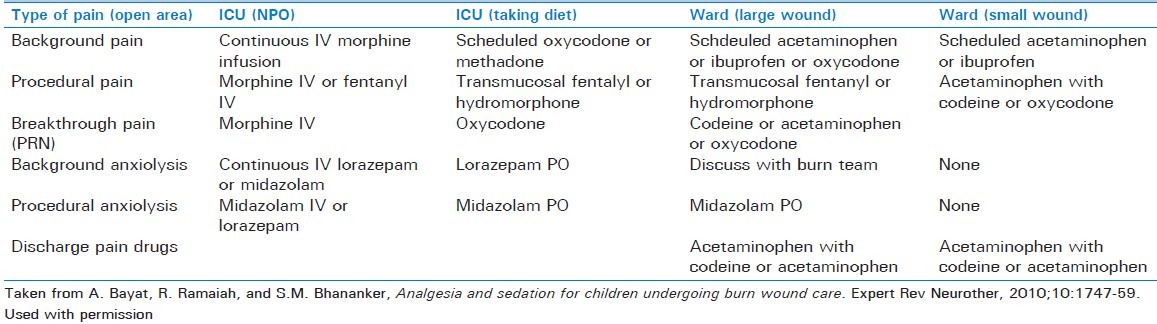

Pain management is a critical piece in the overall care of the burned child. Severe pain is a major consequence of burn injury, and it has been demonstrated that it is often inadequately treated.[50] Anxiety and depression are confounding components in a major burn and can further decrease the pain threshold. The different types of pain must be taken into account (acute, procedure-related pain versus background, or baseline pain) in the development of an effective pain regimen. High-dose opioids are commonly used to manage acute breakthrough pain and pain associated with burn procedures, and morphine is currently the most widely used drug at burn centers in North America.[51] As alterations in morphine clearance do not seem to be an effect of burn injury and most burned patients will develop tolerance to its effects, titration to the appropriate level of pain control and frequent reassessment are important. In addition, the combination of opioids and benzodiazepines (with appropriate monitoring) can be used successfully for procedural sedation, as daily wound care and dressing changes are commonplace and can be associated with significant pain. Table 2 shows a protocol for pain management in burn children from our institution, which is a burn center for the northwest United States.

Table 2.

Harborview Medical Center (WA, USA) for pain management of a pediatric (<40 kg) burn patient

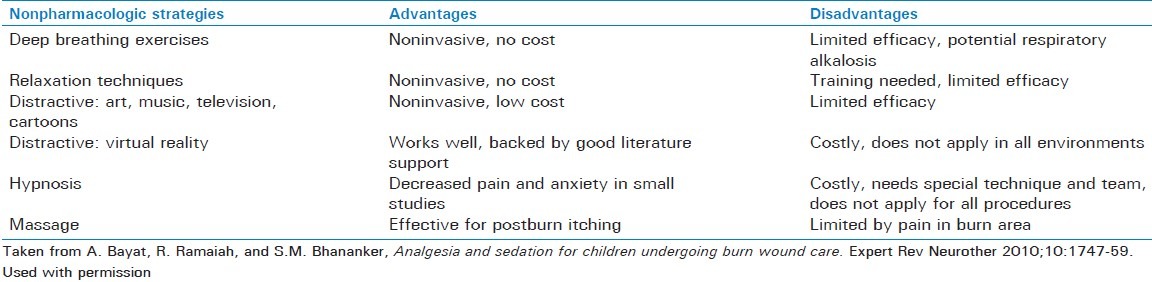

Due to the concerns of tolerance, withdrawal, and opioid-induced hyperalgesia,[52] the use of a multimodal pain management regimen has been advocated. For background analgesia, analgesics such as acetaminophen can be used for their opioid-sparing effect. Ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) antagonist has been used with increased frequency for procedural sedation. Advantages for its use include preserved muscle tone and protective airway reflexes, reduced risk of respiratory depression, and reduced hemodynamic effects.[53] Regional anesthetic techniques may also serve as a useful opioid-sparing adjunct for burn injuries limited to an extremity. Lastly, a variety of other techniques including music therapy, hypnotherapy, massage, behavioral techniques, and even virtual reality techniques have been successfully used to reduce pain during wound care.[54] Table 3 lists some of these techniques, their advantages, and disadvantages.

Table 3.

Nonpharmacologic strategies for pediatric burn pain

CONCLUSION

Burn injury in children continues to be a major epidemiologic problem. Care for these particularly vulnerable patients requires a sound understanding of the multisystemic pathophysiological effects of burn injury on virtually every organ system. In addition, close attention must be paid to initial evaluation and management, resuscitation, and pain control. Through the use of multidisciplinary teams, burn centers, and advancement of knowledge through sustained research efforts, we can continue to offer these patients an excellent chance for recovery.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayat A, Ramaiah R, Bhananker SM. Analgesia and sedation for children undergoing burn wound care. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10:1747–59. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlsson A, Udén G, Håkansson A, Karlsson ED. Burn injuries in small children, a population-based study in Sweden. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:129–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheridan RL, Remensnyder JP, Schnitzer JJ, Schulz JT, Ryan CM, Tompkins RG. Current expectations for survival in pediatric burns. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:245–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrow RE, Spies M, Barrow LN, Herndon DN. Influence of demographics and inhalation injury on burn mortality in children. Burns. 2004;30:72–7. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheridan RL, Ryan CM, Petras LM, Lydon MK, Weber JM, Tompkins RG. Burns in children younger than two years of age: An experience with 200 consecutive admissions. Pediatrics. 1997;100:721–3. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mertens DM, Jenkins ME, Warden GD. Outpatient burn management. Nurs Clin North Am. 1997;32:343–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali SN, O’Toole G, Tyler M. Milk bottle burns. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004;25:461–2. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000138652.29557.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izamis ML, Uygun K, Uygun B, Yarmush ML, Berthiaume F. Effects of burn injury on markers of hypermetabolism in rats. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30:993–1001. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181bfb7b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barber RC, Maass DL, White DJ, Horton JW. Increasing percent burn is correlated with increasing inflammation in an adult rodent model. Shock. 2008;30:388–93. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318164f1cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bessey PQ, Watters JM, Aoki TT, Wilmore DW. Combined hormonal infusion simulates the metabolic response to injury. Ann Surg. 1984;200:264–81. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198409000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill GL, Jonathan E. Rhoads Lecture. Body composition research: Implications for the practice of clinical nutrition. JPEN. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1992;16:197–218. doi: 10.1177/0148607192016003197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill AG, Hill GL. Metabolic response to severe injury. Br J Surg. 1998;85:884–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeschke MG, Chinkes DL, Finnerty CC, Kulp G, Suman OE, Norbury WB, et al. Pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Ann Surg. 2008;248:387–401. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181856241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zak AL, Harrington DT, Barillo DJ, Lawlor DF, Shirani KZ, Goodwin CW. Acute respiratory failure that complicates the resuscitation of pediatric patients with scald injuries. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1999;20:391–9. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199909000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kane TD, Greenhalgh DG, Warden GD, Goretsky MJ, Ryckman FC, Warner BW. Pediatric burn patients with respiratory failure: Predictors of outcome with the use of extracorporeal life support. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1999;20:145–50. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199903000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao SC, Zhu SH, Xia ZF, Lu W, Wang GQ, Ben DF, et al. Prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal dysfunction following severe burns: A summary of recent 30-year clinical experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3231–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yadav RP, Agrawal CS, Gupta RK, Rajbansi S, Bajracharya A, Adhikary S. Perforated duodenal ulcer in a young child: An uncommon condition. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2009;48:165–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sallam HS, Oliveira HM, Liu S, Chen JD. Mechanisms of burn-induced impairment in gastric slow waves and emptying in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R298–305. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00135.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider DF, Dobrowolsky A, Shakir IA, Sinacore JM, Mosier MJ, Gamelli RL. Predicting acute kidney injury among burn patients in the 21st century: A classification and regression tree analysis. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:242–51. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318239cc24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber JM, Sheridan RL, Fagan S, Ryan CM, Pasternack MS, Tompkins RG. Incidence of Catheter-Associated Bloodstream Infection After Introduction of Minocycline and Rifampin Antimicrobial-Coated Catheters in a Pediatric Burn Population [Epub ahead of print] J Burn Care Res. 2012 doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31823c4cd5. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanchet B, Jullien V, Vinsonneau C, Tod M. Influence of burns on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs used in the care of burn patients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47:635–54. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847100-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osta WA, El-Osta MA, Pezhman EA, Raad RA, Ferguson K, McKelvey GM, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene expression is altered in burn patients. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:1355–9. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d41512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perreault S, Choiniere M, du Souich PB, Bellavance F, Beauregard G. Pharmacokinetics of morphine and its glucuronidated metabolites in burn injuries. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:1588–92. doi: 10.1345/aph.10251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madnani DD, Steele NP, de Vries E. Factors that predict the need for intubation in patients with smoke inhalation injury. Ear Nose Throat J. 2006;85:278–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caruso TJ, Janik LS, Fuzaylov G. Airway management of recovered pediatric patients with severe head and neck burns: A review. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22:462–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2012.03795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turnage RH, Nwariaku F, Murphy J, Schulman C, Wright K, Yin H. Mechanisms of pulmonary microvascular dysfunction during severe burn injury. World J Surg. 2002;26:848–53. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-4063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fidkowski CW, Fuzaylov G, Sheridan RL, Cote CJ. Inhalation burn injury in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19(Suppl 1):147–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jauncey-Cooke JI, Bogossian F, East CE. Lung protective ventilation strategies in paediatrics-A review. Aust Crit Care. 2010;23:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cartotto R, Ellis S, Smith T. Use of high-frequency oscillatory ventilation in burn patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(3 Suppl):S175–81. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000157232.31910.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Askegard-Giesmann JR, Besner GE, Fabia R, Caniano DA, Preston T, Kenney BD. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a lifesaving modality in the treatment of pediatric patients with burns and respiratory failure. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1330–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.02.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silver GM, Freiburg C, Halerz M, Tojong J, Supple K, Gamelli RL. A survey of airway and ventilator management strategies in North American pediatric burn units. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004;25:435–40. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000138294.39313.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstein AM, Weber JM, Sheridan RL. Femoral venous access is safe in burned children: An analysis of 224 catheters. J Pediatr. 1997;130:442–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheridan RL, Weber JM. Mechanical and infectious complications of central venous cannulation in children: Lessons learned from a 10-year experience placing more than 1000 catheters. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:713–8. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000238087.12064.E0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheridan RL. Burns. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(11 Suppl):S500–14. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200211001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fodor L, Fodor A, Ramon Y, Shoshani O, Rissin Y, Ullmann Y. Controversies in fluid resuscitation for burn management: Literature review and our experience. Injury. 2006;37:374–9. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts I, Alderson P, Bunn F, Chinnock P, Ker K, Schierhout G. Colloids versus crystalloids for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD000567. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000567.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitra B, Fitzgerald M, Cameron P, Cleland H. Fluid resuscitation in major burns. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:35–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holm C, Melcer B, Horbrand F, Worl HH, von Donnersmarck GH, Muhlbauer W. Haemodynamic and oxygen transport responses in survivors and non-survivors following thermal injury. Burns. 2000;26:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klein GL, Herndon DN. Burns. Pediatr Rev. 2004;25:411–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunter GR, Chang FC. Outpatient burns: A prospective study. J Trauma. 1976;16:191–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wasiak J, Cleland H, Campbell F. Dressings for superficial and partial thickness burns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD002106. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002106.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klasen HJ. A review on the nonoperative removal of necrotic tissue from burn wounds. Burns. 2000;26:207–22. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D’Avignon LC, Saffle JR, Chung KK, Cancio LC. Prevention and management of infections associated with burns in the combat casualty. J Trauma. 2008;64(3 Suppl):S277–86. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318163c3e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kesting MR, Wolff KD, Hohlweg-Majert B, Steinstraesser L. The role of allogenic amniotic membrane in burn treatment. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29:907–16. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31818b9e40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shelley OP, Van Niekerk W, Cuccia G, Watson SB. Dual benefit procedures: Combining aesthetic surgery with burn reconstruction. Burns. 2006;32:1022–7. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kennedy P, Brammah S, Wills E. Burns, biofilm and a new appraisal of burn wound sepsis. Burns. 2010;36:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munster AM, Smith-Meek M, Sharkey P. The effect of early surgical intervention on mortality and cost-effectiveness in burn care, 1978-91. Burns. 1994;20:61–4. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(94)90109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ong YS, Samuel M, Song C. Meta-analysis of early excision of burns. Burns. 2006;32:145–50. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singer AJ, Thode HC., Jr National analgesia prescribing patterns in emergency department patients with burns. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2002;23:361–5. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin-Herz SP, Patterson DR, Honari S, Gibbons J, Gibran N, Heimbach DM. Pediatric pain control practices of North American Burn Centers. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2003;24:26–36. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cuignet O, Pirson J, Soudon O, Zizi M. Effects of gabapentin on morphine consumption and pain in severely burned patients. Burns. 2007;33:81–6. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gregoretti C, Decaroli D, Piacevoli Q, Mistretta A, Barzaghi N, Luxardo N, et al. Analgo-edation of patients with burns outside the operating room. Drugs. 2008;68:2427–43. doi: 10.2165/0003495-200868170-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stoddard FJ, Sheridan RL, Saxe GN, King BS, King BH, Chedekel DS, et al. Treatment of pain in acutely burned children. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2002;23:135–56. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200203000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]