Abstract

The number of children requiring sedation and analgesia for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures has increased substantially in the last decade. Both anesthesiologist and non-anesthesiologists are involved in varying settings outside the operating room to provide safe and effective sedation and analgesia. Procedural sedation has become standard of care and its primary aim is managing acute anxiety, pain, and control of movement during painful or unpleasant procedures. There is enough evidence to suggest that poorly controlled acute pain causes suffering, worse outcome, as well as debilitating chronic pain syndromes that are often refractory to available treatment options. This article will provide strategies to provide safe and effective sedation and analgesia for pediatric trauma patients.

Keywords: Pediatric, adverse events, airway, sedation, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Trauma is one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in children under the age of 14 years. Pain is a universal feature of trauma. Pain is often undertreated in children and this could have serious undesirable long-term effects. The Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium, Society for Pediatric Sedation and other organizations like the Joint Commission have issued guidelines, statements and results from their database that will help in understanding and improving the process of pediatric sedation and sedation outcomes for children. This article reviews the management of traumatized children who require analgesia and sedation for diagnostic and/or therapeutic interventions along with strategies to prevent adverse events during sedation and analgesia.

SEDATION CONTINUUM

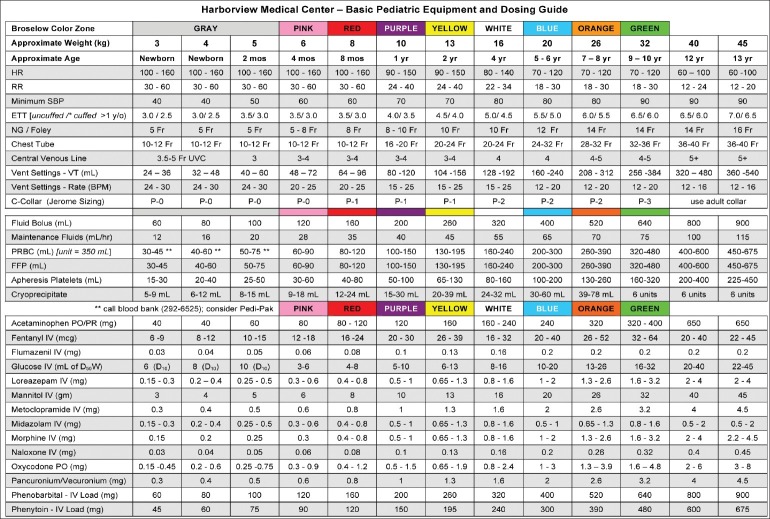

The original guidelines for pediatric sedation were issued by the National Institute of Health and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in 1985. These guidelines were issued in response to the reports of several deaths in a single dental office related to sedation.[1] Besides addressing system issues, they defined three levels of depth of sedation: conscious sedation, deep sedation, and general anesthesia. The choice of this terminology was confusing, as conscious sedation is infrequently attained in children. AAP Committee on drugs revised these guidelines in 1992, and they stated that irrespective of the intended level of sedation or route of administration, children could progress from one level of sedation to another. The same committee published an amendment to these guidelines in 2002.[2] The current guidelines eliminated the use of term conscious sedation and recommended the use of terminology such as minimal sedation, moderate sedation, deep sedation, and general anesthesia to describe the continuum of the sedation spectrum [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Sedation continuum

Many specialty societies and regulatory bodies across the world have published guidelines for procedural sedation and analgesia, however, each one is addressing the guidelines to their perspective. In 2001, the Joint Commission released standards for pain management, sedation, and anesthesia care in the US. They stated that procedural sedation and analgesia practice should be similar across all the locations such as operating room, emergency room, or endoscopy suite. They also recommend US hospitals to develop and enforce institution wide protocols for procedural sedation, and the sedation provider must have skills to manage compromised airway and rescue patients from inadvertent general anesthesia.

Primary goal of sedation and analgesia is to provide anxiolysis, control of pain, and movement during painful or unpleasant procedures. Sedation and analgesia are needed for wide range of procedures in pediatric trauma including but not limited to laceration repair, reduction of bone fractures or joint dislocations, vascular access, or instrumentation (painful procedures) and diagnostic imaging include CT, MRI, and X-rays (non-painful procedures). Some of these procedures may not require sedation and analgesia and can be managed with psychological technique.

PRE-PROCEDURAL FASTING

American society of anesthesiologist (ASA) first published fasting guidelines in 1980s with the main aim of reducing aspiration in anesthetized patients. The initial guideline was developed for healthy patients, undergoing elective surgical procedures, who need general anesthesia and excluded emergency department (ED) patients. Subsequently these guidelines have been extrapolated without adaptation to include procedural sedation and analgesia. The fasting guidelines recommend at least 2 h of fasting for clear liquids, 4 h for breast milk and 6 h for solids.[3] Emergency physicians use more liberal fasting guidelines based on urgency of the procedure, intended level, and duration of sedation and patient associated aspiration risk factors.[4] Three hours fasting is considered sufficient for all levels of sedation for emergency procedures and minimal to moderate sedation for semi-urgent and non-urgent procedure. Unlike other sedatives ketamine preserves protective airway reflexes and may be preferred agent in some clinical situations.

PREPROCEDURAL ASSESSMENT

Pre-procedural health evaluation should be performed by a provider who is appropriately licensed and reviewed by the sedation team.[5] In the US, the Joint Commission has mandated that all children undergoing sedation should have pre-procedural assessment and the hospitals are expected to develop specific documentation records of such evaluation. Pre-sedation health evaluation will also screen children who will require more advanced airway management, special cardiovascular monitoring, or changes to the dose and type of medication used for procedural sedation.

Pre-procedural evaluation should include:

Age and weight of the patient

Obtaining underlying medical history and medication allergies

Performing system review with main focus on cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, and hepatic function, understanding that child's response to medication may be altered

Vital signs should be recorded and documented

A physical examination including airway assessment for abnormalities (obesity, short neck, small mandible, enlarged tonsils, large tongue, and trismus) that might impair airway management

Obtaining contact details of the child's medical guardian

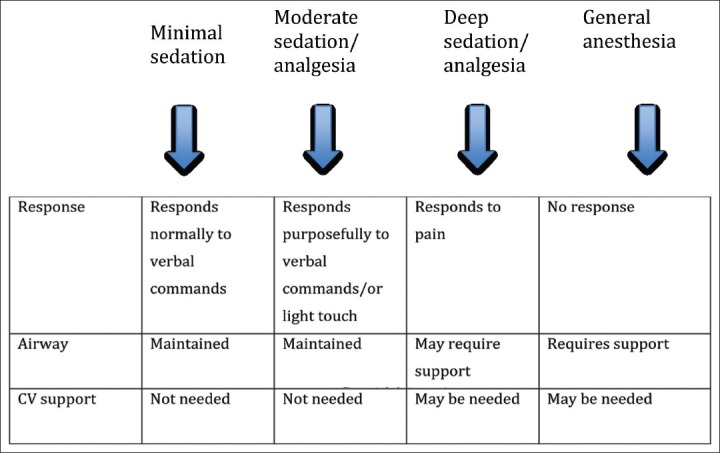

ASA physical status, children with ASA classes 1 and 2 are more likely to be appropriate candidates for all levels of sedation. On the other hand, ASA classes 3 and 4, or those children with special needs require additional and individual considerations, particularly for moderate and deep sedation [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sedation suitability in children

PREPARATION AND SETUP FOR SEDATION AND ANALGESIA

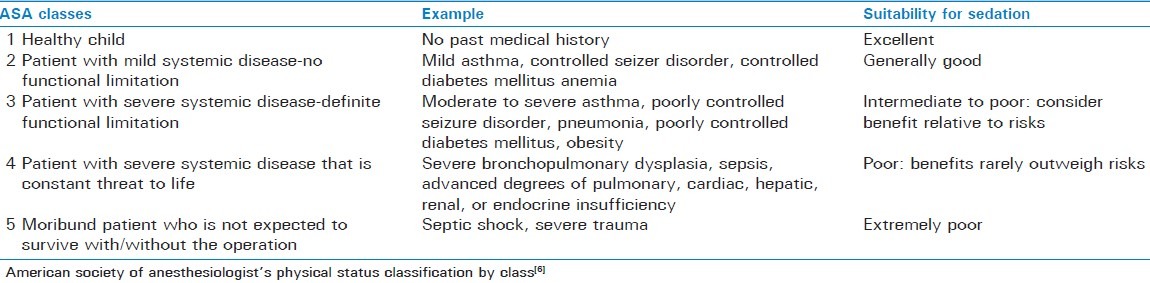

Selection of age appropriate equipment, medication dose, and monitors is critical for safe conduct of procedural sedation in children. A commonly used acronym that is useful in planning and preparation for procedural sedation is SOAPME [Table 2].

Table 2.

SOAPME checklist

EQUIPMENT AND MONITORING

Use of modern monitors has greatly enhanced the safety of procedural sedation especially in remote location with unfamiliar atmosphere. Continuous monitoring of oxygenation using pulse oximeter with audible alarm, respiration-using capnograhy and heart rate (EKG) and intermittent measurement of blood pressure should be documented. Modern pulse oximeters are less susceptible to motion artifact and the oximeters that change the tone with change in the hemoglobin saturation provide immediate warning to everyone within hearing distance.[7] Capnography is an important device to monitor respiration, especially in children undergoing sedation and analgesia in less accessible location, such as MRI, CT scan or in locations with poor light and it has been shown to improve patient safety by reducing number of apnea/hypoxia events during sedation and analgesia.[8] Some of the newer monitors such as BIS (bispectral index) have been useful in titrating propofol dosage to targeted level of sedation in children.[9] All the sedation locations in the hospital should have age appropriate equipment for airway management and resuscitation, including oxygen, a bag-valve mask, working suction and all the medications, and reversal agents with color-coded labels.

PAIN ASSESSMENT IN CHILDREN

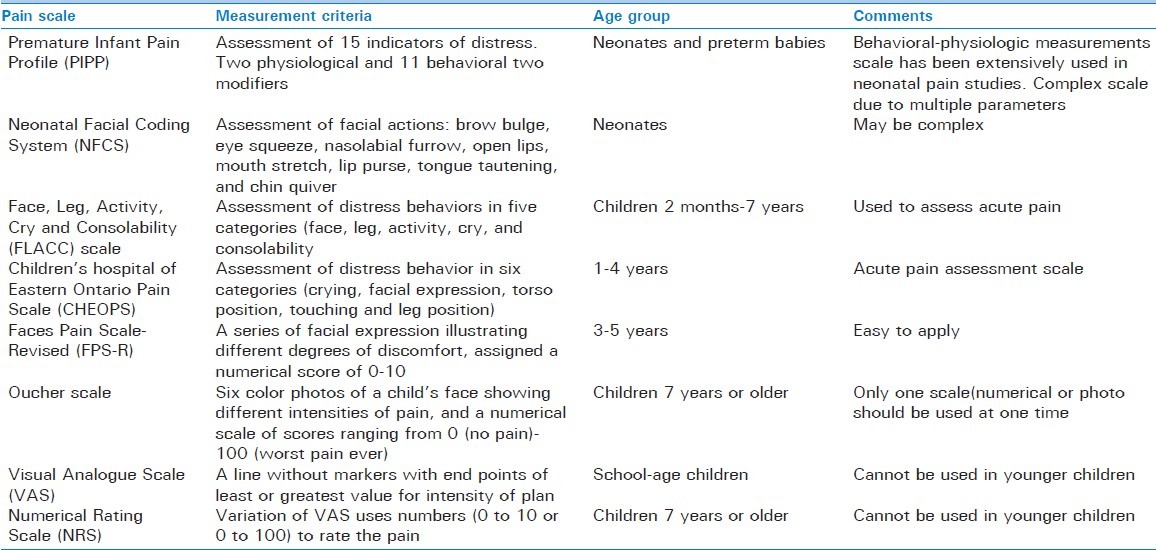

It has been more than a decade since the Joint Commission cited inadequate pain control is the first non-disease healthcare crisis in the United States. Pain research in children in the last three decades has observed that children are given analgesics less often than adults for similar conditions and that they are prescribed only approximately 50% of the weight based equivalent of analgesics.[10] Furthermore, younger children received lower milligram per kilogram dosing regardless of their intensity of pain.[11] It is critical that clinicians make frequent assessment of pain intensity in children to establish the severity and effectiveness of analgesic medication and titrate the dosage. Pain assessment in children is challenging, as there is no single tool available for all age groups, hence age appropriate pain assessment scales should be used. Most validated pain assessment tool such as Wong-Baker Faces scale is generally considered unreliable in younger children (less than 3 years). The visual analog scale is not useful in children younger than 6 years [Table 3]. Besides self-reporting pain assessment scales, consideration should be given to the behavioral and physiological changes while assessing pain in children. Commonly used pain assessment scales and tool are shown in Table 3. International Association for the Study of Pain has revised faces pain scale; a self reported measure to assess the pain intensity in children this was originally adopted from Faces Pain Scale[12] [Figure 2]. This revised scale incorporates several changes from original faces pain scale, including adaptation of common metric (0-10),[13] and the removal of “smiling face and tears” anchors to avoid the confounding of affect and pain intensity. Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R) consist of six faces, visually representing increasing changes in the intensity of pain with extreme left side being no pain and extreme right side is very much pain as shown in Figure 2. FPS-R can be used to assess pain intensity in children age group 4 years to 16 years.

Table 3.

Pain assessment tools in children of different ages

Figure 2.

Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R) @2001 International Association for the Study of Pain

MEDICATIONS FOR SEDATION AND ANALGESIA

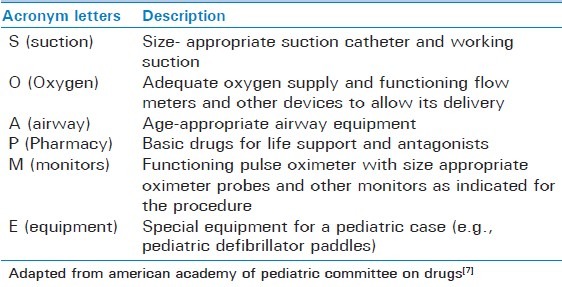

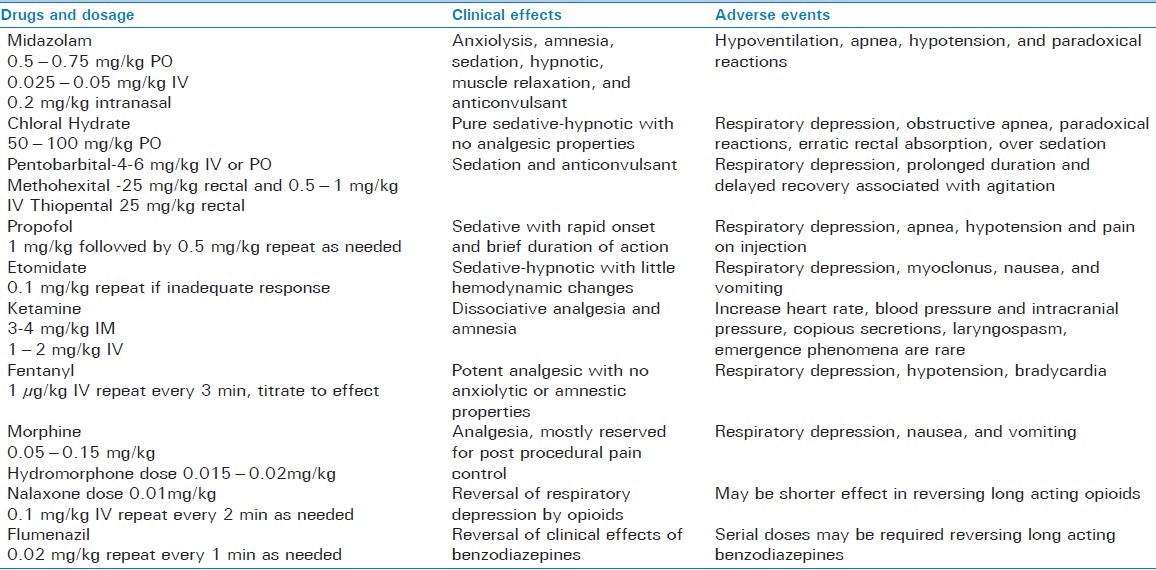

Selection of medication and targeted level of sedation should depend on individual needs and whether the procedure is going to painful or non-painful. Painful procedures require deeper level of sedation along with analgesic; on the other hand, non-painful procedures such as diagnostic imaging will need minimal to moderate sedation. The medication used for sedation and analgesia includes sedatives-hypnotics, analgesics, and/or dissociative agents to relieve anxiety and pain associated with diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in children with injury. Careful planning in selection of medication and monitoring in infants and children less than 6 months and in children with hepatic or renal impairment is critical, as these patients will have delayed metabolism and excretion. Commonly used drugs and their adverse event are shown in Table 4 along with antagonists. Basic pediatric sedation equipment and dosing guide are shown in Figure 3. Most widely used medications are sedative-hypnotics such as benzodiazepines (e.g., midazolam), barbiturates (e.g., pentobarbitol, methohexitol and thiopental) and other classes of medication (e.g., propofol, ketamine, etomidate, and chloral hydrate).[14] Ultra-short acting agents such as propofol, etomidate, methohexitol, and thiopental have rapid onset with brief duration of action and allow additional doses if it is required for the procedure. Use of propofol for pediatric sedation is well established due to its favorable pharmacokinetic properties such as rapid onset and recovery along with the absence of nausea and emergence phenomenon.[15,16] All the sedative-hypnotic agents do not have specific analgesic properties and when they are used for painful procedures, and frequently need supplementation with opioids (e.g., fentanyl, morphine).[14] Other sedation technique includes dissociative sedation using ketamine and inhalational sedation with use of nitrous oxide alone or in combination with opioids/nerve blocks. In the recent years there is much excitement to use “ketofol” (combination of ketamine and propofol) in ED in North America as their primary sedation regime, however there is some controversy regarding its use in the ED. Pro argument is that there is substantial evidence to support use of ketofol in the ED. It is safe, effective, and popular among ED physicians. Ketamine mitigates propofol-induced hypotension and propofol mitigates ketamine-induced vomiting and recovery agitation. Ketofol exhibits synergistic property with smoother sedation and reducing total dose of propofol and obviating need for opioid use. Con argument is that ketofol is nothing more than standard propofol sedation where fentanyl is replaced by subdissociative dose of ketamine.[17] Before ketofol can be recommended for pediatric sedation in ED, there need to be more evidence that combination of drugs offer a tangible benefit over either agent alone.

Table 4.

Pharmacological agents used for sedation and analgesia and reversal drugs

Figure 3.

The Broselow length-based system as modified for use at the Pediatric Level 1 Trauma Center at Harborview Medical Center (Seattle WA)

ROUTES OF ADMINISTRATION

If the intended level of sedation is deep, than child should have intravenous access placed at the start of the procedure. Titration of medication to patient's response using intravenous route provides rapid action and safe analgesia and sedation. Establishing intravenous access may be difficult especially in children who are very anxious or combative. Oral, transmucosal (intranasal, rectal), and intramuscular routes are more convenient especially in children who are uncooperative or have difficult intravenous access. These routes of administration are also useful in non-painful procedures such as diagnostic imaging; however, they are less reliable for dose titration and can result in erratic absorption with variable onset and duration of action. Individual needs can vary and application of arbitrary ceiling of medication doses whether an absolute dose in mg or doses based on body weight may not be appropriate to achieve the targeted level of sedation. Dosage should be titrated to the dose required to provide adequate control of pain or sedation without major cardiorespiratory adverse events.

AFTER PROCEDURE

Following sedation and analgesia all children should be monitored in a well-equipped recovery location until they are no longer at risk for cardiorespiratory depression and their vital signs are stable.[5] The recovery location should have at minimum suction apparatus, capability to provide more than 90% oxygen, and positive pressure ventilation (pediatric breathing circuit or bag-valve mask). If the child is not fully awake and alert, monitoring should be continued until appropriate discharge criteria are met. Children who have received long acting medication (e.g., chloral hydrate) or reversal agents (e.g., naloxone, flumazenil) will require extended period of observation, since the half life of reversal agents is short. Many hospitals utilize same recovery-scoring system, as used in surgical post anesthesia care unit. Appropriate instructions should be given to reliable adult regarding diet, medication, and activity level in the next 24 h.

ADVERSE EVENTS DURING PEDIATRIC SEDATION AND ANALGESIA

Patient safety is one of the most important aspects of sedation and analgesia, which can be achieved by minimizing complications. Adverse events in children during procedural sedation can occur secondary to wide range reasons including drug error and/or overdose, inadequate monitoring, inadequate skills of the personnel providing sedation, and premature discharge.[18] Majority of complications (80%) during sedation and analgesia are secondary to adverse airway/respiratory events.[19,20] Most of these adverse events can be managed with simple maneuvers, such as administering supplemental oxygen, opening the airway with jaw thrust, suctioning, and using bag-mask-valve ventilation. Rarely, a more advanced airway support such as endotracheal intubation or use of laryngeal mask airway (LMA) is required. Sedation related adverse events are rare, however at present there are no well-established terminology or definitions to describe adverse events. International sedation taskforce has attempted to address these problems and designed tools to report adverse events related to sedation for widespread adoption.[21] This type of reporting, not only standardize definitions but will provide opportunity to evaluate sedation practice and outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Sedation and analgesia for pediatric trauma are rapidly expanding and is subjected to evolving changes and advances to the way we practice. Anesthesiologist along with other specialty groups have played important role in establishing guidelines for safe practice of sedation. In the future, hospitals will likely to set-up multidisciplinary pediatric sedation teams that will not only administer procedural sedation, but will also be responsible for training and credentialing for all non-anesthesiologists in procedural sedation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goodson JM, Moore PA. Life-threatening reactions after pedodontic sedation: An assessment of narcotic, local anesthetic, and antiemetic drug interaction. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983;107:239–45. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1983.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Drugs. American Academy of Pediatrics. Guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures: Addendum. Pediatrics. 2002;110:836–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green SM, Roback MG, Miner JR, Burton JH, Krauss B. Fasting and emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia: A consensus-based clinical practice advisory. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:454–61. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green SM. Fasting is a consideration--not a necessity--for emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:647–50. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(03)00636-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connor RE, Sama A, Burton JH, Callaham ML, House HR, Jaquis WP, et al. Procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department: Recommendations for physician credentialing, privileging, and practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:365–70. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krauss B, Green SM. Procedural sedation and analgesia in children. Lancet. 2006;367:766–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramaiah R, Bhananker S. Pediatric procedural sedation and analgesia outside the operating room: Anticipating, avoiding and managing complications. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11:755–63. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qadeer MA, Vargo JJ, Dumot JA, Lopez R, Trolli PA, Stevens T, et al. Capnographic monitoring of respiratory activity improves safety of sedation for endoscopic cholangiopancreatography and ultrasonography. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1568–76. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.004. quiz 819-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powers KS, Nazarian EB, Tapyrik SA, Kohli SM, Yin H, van der Jagt EW, et al. Bispectral index as a guide for titration of propofol during procedural sedation among children. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1666–74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schechter NL. The undertreatment of pain in children: An overview. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1989;36:781–94. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36721-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedland LR, Kulick RM. Emergency department analgesic use in pediatric trauma victims with fractures. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:203–7. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bieri D, Reeve RA, Champion GD, Addicoat L, Ziegler JB. The Faces Pain Scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: Development, initial validation, and preliminary investigation for ratio scale properties. Pain. 1990;41:139–50. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. The Faces Pain Scale-Revised: Toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93:173–83. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahyoun C, Krauss B. Clinical implications of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of procedural sedation agents in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012;24:225–32. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283504f88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green SM. Propofol in emergency medicine: Further evidence of safety. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:389–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallory MD, Baxter AL, Yanosky DJ, Cravero JP. Emergency physician-administered propofol sedation: A report on 25,433 sedations from the pediatric sedation research consortium. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:462–8 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green SM, Andolfatto G, Krauss B. Ketofol for procedural sedation.? Pro and con. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:444–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malviya S, Voepel-Lewis T, Tait AR. Adverse events and risk factors associated with the sedation of children by nonanesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:1207–13. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199712000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cote CJ, Notterman DA, Karl HW, Weinberg JA, McCloskey C. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: A critical incident analysis of contributing factors. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 Pt 1):805–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cote CJ. Anesthesia-related cardiac arrest in children. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:933. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200105000-00038. author reply 34-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason KP, Green SM, Piacevoli Q. Adverse event reporting tool to standardize the reporting and tracking of adverse events during procedural sedation: A consensus document from the World SIVA International Sedation Task Force. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:13–20. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]