Abstract

Context:

Though some studies have described traumatic brain injuries in tertiary care, urban hospitals in India, very limited information is available from rural settings.

Aims:

To evaluate and describe the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with traumatic brain injury and their clinical outcomes following admission to a rural, tertiary care teaching hospital in India.

Settings and Design:

Retrospective, cross-sectional, hospital-based study from January 2007 to December 2009.

Materials and Methods:

Epidemiological and clinical data from all patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) admitted to the neurosurgery service of a rural hospital in district Wardha, Maharashtra, India, from 2007 to 2009 were analyzed. The medical records of all eligible patients were reviewed and data collected on age, sex, place of residence, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, mechanism of injury, severity of injury, concurrent injuries, length of hospital stay, computed tomography (CT) scan results, type of management, indication and type of surgical intervention, and outcome.

Statistical Analysis:

Data analysis was performed using STATA version 11.0.

Results:

The medical records of 1,926 eligible patients with TBI were analyzed. The median age of the study population was 31 years (range <1 year to 98 years). The majority of TBI cases occurred in persons aged 21 - 30 years (535 or 27.7%), and in males (1,363 or 70.76%). Most patients resided in nearby rural areas and the most frequent external cause of injury was motor vehicle crash (56.3%). The overall TBI-related mortality during the study period was 6.4%. From 2007 to 2009, TBI-related mortality significantly decreased (P < 0.01) during each year (2007: 8.9%, 2008: 8.5%, and 2009: 4.9%). This decrease in mortality could be due to access and availability of better health care facilities.

Conclusions:

Road traffic crashes are the leading cause of TBI in rural Maharashtra ffecting mainly young adult males. At least 10% of survivors had moderate or more severe TBI-related disabilities. Future research should include prospective, population based studies to better elucidate the incidence, prevalence, and economic impact of TBI in rural India.

Keywords: Head injury, India, rural, traumatic brain injury

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) are a steadily increasing and major cause of morbidity, mortality, and loss of productivity in resource-limited settings, particularly among younger age groups in the second to fourth decades of life.[1–4] Economic development has resulted in rapid urbanization, motorization, and population migration, altering traditional methods of living and working.[5] The rapid motorization of India, especially during the past two decades, has resulted in increasing numbers of injuries and deaths due to road traffic crashes.[5] After injuries occur, many challenges exist for appropriate and effective pre-hospital and trauma care including an inadequate transport system, and logistical and infrastructure deficiencies. Many studies from India have described the epidemiology of TBI and discussed related issues, including the need for public awareness campaigns and enforcement of legislation to reduce the number of injuries.[2,5–15] Most of these studies have been conducted in large urban trauma centers. There is a lack of reliable data regarding TBI in rural settings.[5,14,15] The present study is aimed to describe epidemiological characteristics of TBI and selected related clinical outcomes in this rural setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting

The Vidarbha region in Maharashtra state (includes Akola, Buldana, Washim, Amravati, Nagpur, Chandrapur, Gondia, Bhandara, Yavatmal, Gadchiroli, and Wardha districts) is a rural area in central India and home to approximately 3.4 million cotton farmers.[16] Many residents are economically disadvantaged, often because they are struggling with significant agricultural debt.[17,18] The Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences (DMIMSU) and the associated Acharya Vinoba Bhave Rural Hospital (AVBRH) comprise a 1215 -bed tertiary care teaching hospital organization serving the rural population of Wardha and surrounding districts. Wardha district (population 1.2 million) has 108 kilometers of four-lane highway and 1200 kilometers of state and district roads (Source Wardha district website http://wardha.nic.in).[16] There are about 70000 registered vehicles in the district (84% two wheelers, 11% cars and light motored vehicles, and 5% tractors and heavy motored vehicles) (Source Wardha district website http://wardha.nic.in).[16] Because of the agrarian nature of the region, roads are shared by agricultural workers, livestock, and personal vehicles (Source Wardha district website http://wardha.nic.in).

Design and ethics statement

We conducted a retrospective medical record review of all patients having head injury admitted to AVBRH between January 2007 to December 2009. The study protocol was approved by the DMIMSU institutional ethical committee, who provided a waiver of consent.

Study variables

Medical records of all patients admitted to the neurosurgery service of the hospital and receiving a diagnosis of TBI were examined. Abstraction of medical records included entering the following variables into an electronic database: age, sex, place of residence, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score,[19] mechanism of injury, severity of head injury [defined as mild (GCS- 13-15), moderate (GCS- 9-12) and severe (GCS-3-8)], associated injuries, length of hospital stay (days), computed tomography (CT) results, type of management, surgical intervention (if any), discharge disposition (died vs. discharged alive), and Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score.[20]

All patients were evaluated and resuscitated following established hospital guidelines for management of TBI. In circumstances where CT scan was indicated but unavailable, (e.g. equipment maintenance, operator unavailability, etc) skull X-ray was performed. When indicated, cervical spine X-rays were performed. Long-term outcome data were not available as most patients were lost to follow-up.

Statistical analysis

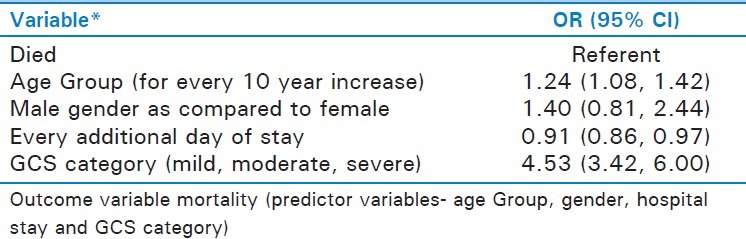

We performed a descriptive analysis of the collected variables to understand the age-group, cause of injury, and imaging findings among patients. We also described the outcome with respect to the Glasgow coma scale on admission. Appropriate tests of significance were used (t-test for difference in means for continuous variables and chi square test for difference in proportions for dichotomous variables). Further, we performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis, to identify significant independent predictors of mortality. Four plausible explanatory variables were included in the model (age group in 10-year intervals), sex, duration of hospital stay in days, and neurological severity as measured by the standard GCS categories. These variables were selected as these were likely to be most plausible reasons for mortality, and these were consistently collected from most patients in the chart review. This was the only model which was evaluated, with an aim to identify which of these variables is most predictive of mortality. Data analysis was performed using STATA version 11.0 (College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

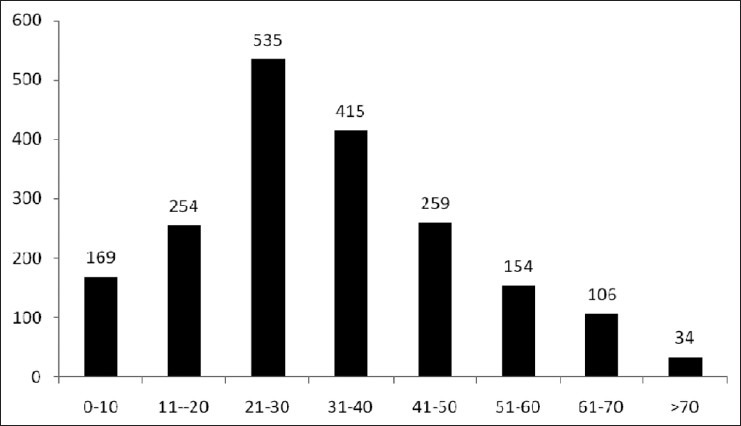

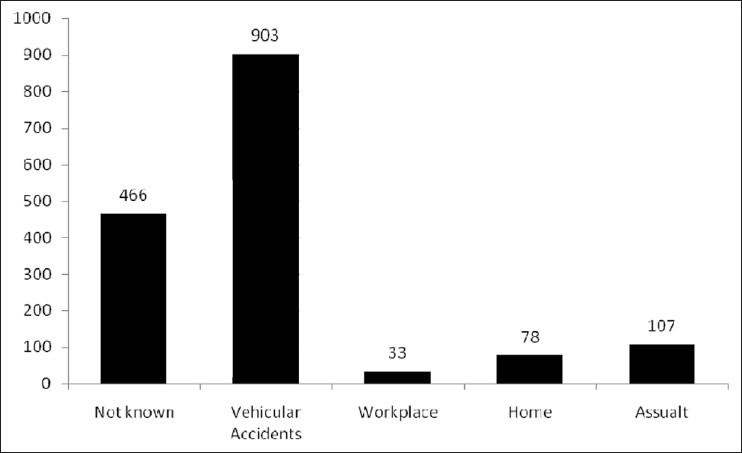

During the study period, 1,926 patients with TBI were admitted to the neurosurgery service. The median age was 31 years (range < 1 year to 98 years). Persons aged 21 to 30 and 31 to 40 years comprised 535 (27.7%) and 415 (21.5%) of the patients, respectively [Figure 1]. Most patients were males (1461 or 75.9%). The number of patients admitted with TBI during the study period, increased by year (376 patients in 2007, 612 patients in 2008 and 938 patients in 2009, respectively). Mean duration between the time since injury and the time elapsed before seeking medical consultation was 8.6 hours in present study. Additionally, during each year of the study, TBI admissions experienced a bimodal peak, during the months of March to June and from October to November. The most common mechanism of injury was road traffic crashes 903 (46.8%), however the mechanism of injury was not available for 466 (29.4%) of patients [Figure 2]. Most patients (90%) presenting with TBI resided within a 35 kilometer radius of the hospital. The mean hospital stay was 6.2 ± 8.1 days (range < 1 day to 87 days).

Figure 1.

Numbers of patients with traumatic brain injury by age group admitted to Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences - Acharya Vinoba Bhave Rural Hospital, Maharashtra, India, January 2007 – December 2009

Figure 2.

Numbers of patients with traumatic brain injury admitted to Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences by selected injury mechanism and injury locale - Acharya Vinoba Bhave Rural Hospital, Maharashtra, India, January 2007 – December 2009

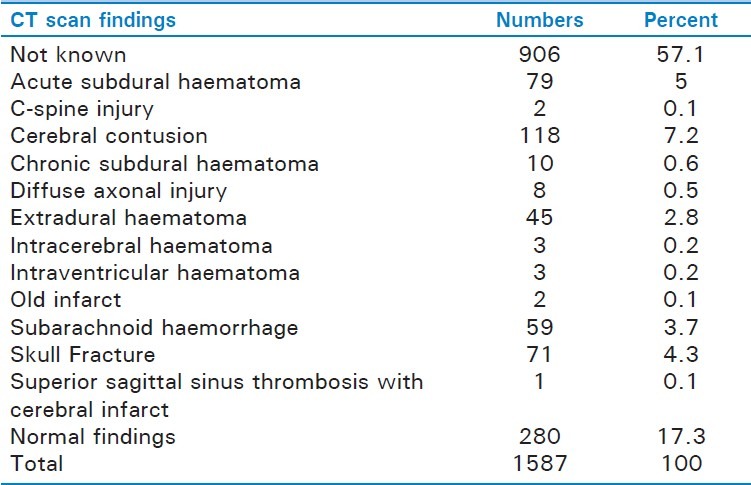

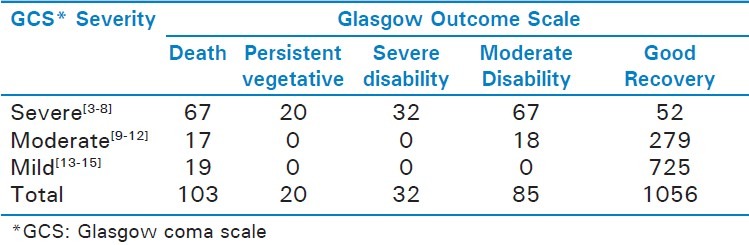

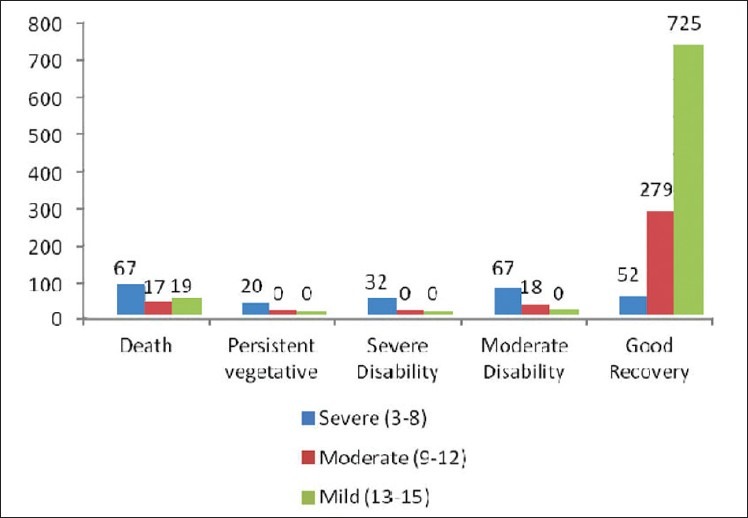

Although the overall mortality was 6.4%, during the study period there was a significant decrease in TBI mortality observed (8.9% in 2007, 8.5% in 2008, and 4.9 in 2009; P value = 0.01). Of the 123 deaths, 86 (69.9%) were among persons aged 21-50 years. Mild TBI occurred in 921 (58%) patients; moderate in 314 (21.5%); and 238 (15.0%) had severe TBI.[19] Cerebral contusions and skull fractures were the most common available radiological diagnoses (7.2 and 4.3%, respectively); results were not available for approximately 57% of the 1587 available CT scan [Table 1]. Concurrent injuries included facial and spinal injuries (643, 40.5%; 11, 0.8%; respectively). Most of the patients (89.5%) were managed conservatively and the main indications for surgery were acute subdural hematomas, extradural hematomas, cerebral contusions and compound depressed fractures. Good recovery (independent for day-to-day activities) was seen in 1056 (66.5%), mild disability was seen in 31.1% patients and severe disability (dependent for day-to-day activities) was seen in 32 (2.4%) of the patients [Table 2]. Of the available data on severity of TBI and mortality (103/123 deaths), the majority (67, 54.4%) occurred in patients presenting with severe TBI followed by in moderate and minor head injuries [Figure 3]. Multivariate logistic regression for risk of mortality suggests that increased TBI severity had a significant association with mortality, and every additional day of hospital stay was associated with decrease in mortality [Table 3].

Table 1.

Number and percent of computerized tomography scan findings among traumatic brain injury patients admitted to Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences-Acharya Vinoba Bhave Rural Hospital, Maharasthra, India, January 2007-December 2009

Table 2.

Numbers of patients with traumatic brain injury by glasgow coma scale and glasgow outcome scale admitted to Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences-Acharya Vinoba Bhave Rural Hospital, Maharasthra, India, January 2007-December 2009

Figure 3.

Severity of head injury and outcome (n= 1587)

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis results of evaluation of association between selected demographic characteristic and mortality among patients with traumatic brain injury admitted to Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences - Acharya Vinoba Bhave Rural Hospital, Maharashtra, India, January 2007-December 2009

DISCUSSION

This study found that in rural Vidarbha head injury mostly affects young men, mostly due to vehicular accidents. These injuries resulted in a spectrum of imaging features and expected pathology. Low Glasgow coma score at admission was significantly associated with mortality as an outcome. This report is similar to many other reports from urban India, and other parts of the world, as there is a disproportionate burden of motor vehicle-related injury morbidity and mortality.[4,6,7,21–23]

This retrospective chart review, is one of the firsts from rural India, and included all consecutive cases which presented to a teaching hospital. This study also has certain limitations. First, being a retrospcetive study only those variables could be studied, which are collected for standard clinical care. We could not collect information about important indicators such as velocity of impact, type of road where accident ocurred, and post-discharge outcome of patients. Second, it is plausible that only a certain proportion of all traumatic brain injuries will reach the hospital, and many of those with severe injuries may have died in the pre-hospital setting, and many with mild injuries may not have sought clinical care. Further, as this was the only neurosurgery equipped hospital in the district at the time of the study, referral bias is also possible. Last, while the results may be typical of rural India, but being a single center study the findings may not be generalizable to other settings.

It is important to understand the dynamics of vehicular injuries in rural India. Most vehicle ownership is in the urban areas, and those vehicles which are owned by rural population are typically low-speed (such as tractors and two-wheelers. However, a vast number of highways pass through rural and remote areas with extensive use of heavy motor vehicles travelling at high speed. Residential areas and highways are not segregated, and safety laws are not universally applied. Many interventions (e.g., road lighting, traffic signals, guard railing, seatbelts, helmets, airbags, and antilock brakes) have also demonstrated success in more industrialized setting and are likely to be valuable in resource-constrained setting such as India.[5,24–28] For example, in the United States, the rate of motor vehicle-related TBI fatalities decreased substantially from 11.4/100,000 in 1979 to 6.6/100,000 in 1992.[29] This decrease was largely attributed to an increase in seat belt and child safety seat use, standardized implementation of air bags, infrastructure investments and improved safety engineering.[30] In India, vehicles, especially those designed locally; do not conform to international safety standards in materials or design (e.g., roll-over prevention or passenger ejec tion).[6]

There is a need to improve pre-hospital care to reduce morbidity and mortality.[31] Apart from safety laws, prompt transport to a hospital after an accident is another important measure to reduce mortality.[32,33] The majority of patients in India are brought to the emergency department by relatives or bystanders in private vehicles, and pre-hospital emergency medical services remain under-organized. Field triage often relies on bystanders who transport injured victims to the nearest clinic, which is often unable to provide appropriate treatment.[15] Major urban areas also have a loosely networked trauma system, untrained emergency medical services personnel and unequipped ambulances.[15] Our observation of family and bystander transport supports the notion that pre-hospital care in rural India requires much improvement. In the present study the mortality in patients with shorter stay was higher probably due to rapid patient death from more severe injuries. Although alcohol use-related data were not available in our study, identifying alcohol-related TBI rates would be crucial to develop public health intervention programs in India.

Additionally, during each year of the study, TBI admissions experienced a bimodal peak, during the months of March to June and from October to November. These months coincide with the planting and harvesting season of the province. However, there is further need to confirm this pattern as it would be useful to plan preventive strategies.

CONCLUSION

The study highlights the TBI in rural areas is mostly among the young male population and is increasing every year with majority coming from nearby villages which is very alarming and highlights the need for taking urgent steps for establishing good pre-hospital care and provision of trauma services at site in India. Mortality is 6.4% with the majority of deaths occurring among persons in the most productive age groups. Recovery with minimal disability was observed in only approximately 60% of cases in this sample. Availability of good neurosurgical care is essential for these patients. A computerized trauma registry is urgent required to bring out the risk factors, circumstances, chain of events leading to the accidents and will be extremely helpful in policy making and health management at the national level in India.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Donagi A, Bing Y. Road traffic accidents in Israel: A report prepared for the Conference on Road Traffic Accidents in Developing Countries, Mexico City, 9-13 November 1981, upon request of WHO. [Tel-Aviv]: State of Israel Israel Police. 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gururaj G. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injuries: Indian scenario. Neurol Res. 2002;24:24–8. doi: 10.1179/016164102101199503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oertel M, Kelly DF, McArthur D, Boscardin WJ, Glenn TC, Lee JH, et al. Progressive hemorrhage after head trauma: Predictors and consequences of the evolving injury. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:109–16. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.1.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajracharya A, Agrawal A, Yam B, Agrawal C, Lewis O. Spectrum of surgical trauma and associated head injuries at a university hospital in eastern Nepal. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2010;1:2–8. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.63092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gururaj G. Burden of disease in India: Equitable development—Healthy future. New Delhi: National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2005. Injuries in India: A National Perspective; pp. 325–47. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coronado VG, Thurman DJ, Greenspan AI, Weissman BM. Epidemiology. In: Jallo E, Loftus CM, editors. Neurotrauma and Critical Care of the Brain. Thieme, New York: Stutgart; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pathak A, Desania NL, Verma R. Profile of Road Traffic Accidents & Head Injury in Jaipur (Rajasthan) J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 2008;30:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghosh PK. Epidemiological study of the victims of vehicular accidents in Delhi. J Indian Med Assoc. 1992;90:309–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh H, Dhattarwal SK. Pattern and distribution of injuries in fatal road traffic accidents in Rohtak (Haryana) J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 2004;26:20–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srivastav AK, Gupta RK. A study of fatal road accidents in Kanpur. J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 1989;11:24–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biswas G. Pattern of road traffic accidents in North-East Delhi. J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2003;20:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menon A, Pai VK, Rajeev A. Pattern of fatal head injuries due to vehicular accidents in Mangalore. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008;15:75–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santhanam R, Pillai SV, Kolluri SV, Rao UM. Intensive care management of head injury patients without routine intracranial pressure monitoring. Neurol India. 2007;55:349–54. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.37094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bither S, Mahindra U, Halli R, Kini Y. Incidence and pattern of mandibular fractures in rural population: A review of 324 patients at a tertiary hospital in Loni, Maharashtra, India. Dent Traumatol. 2008;24:468–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2008.00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhole AM, Potode R, Agrawal A, Joharapurkar SR. Demographic profile, clinical presentation, management options in cranio-cerebral trauma: An experience of a rural hospital in Central India. Pak J Med Sci. 2007;23:724–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Source Wardha district website. [Last accessed on 2010 August 31]. http://wardha.nic.in .

- 17.Behere PB, Bhise MC. Farmers’ suicide: Across culture. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:242–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behere PB, Behere AP. Farmers’ suicide in Vidarbha region of Maharashtra state: A myth or reality? Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:124–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.42401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet. 1975;1:480–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92830-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nantulya VM, Reich MR. The neglected epidemic: Road traffic injuries in developing countries. BMJ. 2002;324:1139–41. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7346.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzharris M, Dandona R, Kumar GA, Dandona L. Crash characteristics and patterns of injury among hospitalized motorised two-wheeled vehicle users in urban India. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garg N, Hyder AA. Exploring the relationship between development and road traffic injuries: A case study from India. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16:487–91. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luna GK, Copass MK, Oreskovich MR, Carrico CJ. The role of helmets in reducing head injuries from motorcycle accidents: A political or medical issue? West J Med. 1981;135:89–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thurman DJ, Burnett CL, Beaudoin DE, Jeppson L, Sniezek JE. Risk factors and mechanisms of occurrence in motor vehicle-related spinal cord injuries: Utah. Accid Anal Prev. 1995;27:411–5. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(94)00059-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lateef F. Riding motorcycles: Is it a lower limb hazard? Singapore Med J. 2002;43:566–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eid HO, Abu-Zidan FM. Biomechanics of road traffic collision injuries: A clinician's perspective. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:693–700. quiz 700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gururaj G. Road traffic deaths, injuries and disabilities in India: Current scenario. Natl Med J India. 2008;21:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sosin DM, Sniezek JE, Waxweiler RJ. Trends in death associated with traumatic brain injury, 1979 through 1992.Success and failure. JAMA. 1995;273:1778–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nantulya VM, Sleet DA, Reich MR, Rosenberg M, Peden M, Waxweiler R. Introduction: The global challenge of road traffic injuries: Can we achieve equity in safety? Inj Control Saf Promot. 2003;10:3–7. doi: 10.1076/icsp.10.1.3.14109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhatoe HS. Brain Injury and prehospital care: Reachable goals in India. Indian J Neurotrauma (IJNT) 2009;6:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knudson P, Frecceri CA, DeLateur SA. Improving the field triage of major trauma victims. J Trauma. 1988;28:602–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198805000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.West JG, Murdock MA, Baldwin LC, Whalen E. A method for evaluating field triage criteria. J Trauma. 1986;26:655–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]