Abstract

Background:

Injuries affect the lives of 10 – 30 million children and adolescents each year and have been acknowledged as the leading cause of mortality among young people in the age range of 15 – 19 years. Injury, as a research problem has been largely ignored in developing countries like Nigeria.

Aims:

This study was aimed at determining injury prevalence, external causes / mechanism of injury, various factors affecting injury occurrence, injury severity, type of treatment received, as well as the most common days and times of injury.

Settings and Design:

The study was conducted in the Agbor Metropolis of the oil-rich Niger delta region of Nigeria and adopted a cross-sectional study design.

Materials and Methods:

Semi-structured questionnaires were distributed to 386 subjects selected using a stratified and simple random technique.

Analysis:

Analysis was done using Social Science Statistical Package, with the level of significance taken at 0.05

Results:

Injury prevalence was 284 (73.6%) with a mean frequency of 1.8 per child. About (221) 57.3% of the injuries sustained resulted in 1+ day's activity loss, with about 136 (35.2%) requiring medical attention. The top injury sites were street / road, 49 (12.69%) and school environment and sporting arena, 47 (12.18%), respectively, followed by home vicinity, 43 (11.14%). The key causes of injury were collision, 53 (13.73%), falling, 41 (10.62%), and cut / stabbing, 41 (7.51%). Most treatments were at the hospital, 136 (47.72%). Most injuries occurred in the afternoons, 108 (28%) and evenings, 89 (23.1%). Injury experience was associated with Respondents / Parents level of education, family type, alcohol consumption, and age (P < 0.05 for all).

Conclusion:

Injury experience was relatively high and varied with site, activity, age, family type, alcohol consumption, and parental educational status.

Keywords: Epidemiology, injury, non-fatal, Nigeria, young people, adolescents

INTRODUCTION

Injuries represent 12% of the global burden of disease with almost 16000 people dying every day from injuries.[1] With epidemiological transition being experienced by many developing countries, injury is assuming importance.[2] It is rapidly becoming one of the leading causes of deaths and disability especially among adolescents and young adults despite the recent spread of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and resurgence of malaria except perhaps in some countries.[3–5] Injury is the most common cause of death and permanent disability in the age group of 1 – 40 years, in industrialized countries, and is also becoming common in low-income countries such as Nigeria.[6] Compared with other age groups, young people of age 15 to 29 years have been reported to account for the highest proportion of all unintentional injuries and resultant deaths.[7]

Injuries affect the lives of 10 – 30 million children and adolescents each year. Reducing this substantially preventable burden requires the collation and interpretation of the existing data on childhood injury, to contribute to hypothesis generation and intervention development.[8] Injury, as a research problem has been largely ignored in developing countries[9,10] It is obvious that with increasing urbanization, poverty, and interest in sports in Nigeria, injury prevalence is bound to increase, especially among adolescents. It is therefore the aim of this article to describe the injury situation among urban Nigerian adolescents, with the implicit aim of drawing the attention of the stakeholders to the risk imposed by injury, hence setting the stage for injury surveillance advocacy. The study reports injury prevalence, mechanism / external causes, activities leading to injury, injury severity, place of injury, treatment received, time and days of injury, and so forth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study location

The study was conducted in the Agbor metropolis — the local government headquarters of Ika south, very close to Asaba, the capital city of Delta state — a core state in the Nigerian oil-rich Niger Delta region. With a population of about 1.2 million according to the 2001 census, it is rich in trade, educational and sporting activities, and so on.

Study design / sample size

A cross-sectional study design was used to collect data on the 386 subjects determined, based on the prevalence of 41.3% obtained from a similar published study.[11] A confidence interval of 95% and absolute precision of 0.05 were used

Study population

The study population were adolescent in senior secondary schools in the metropolis, Which of course constitutes the dominant population of adolescents in the metropolis.

Data collection instrument / Informed consent

A 21-item questionnaire was developed based on questions adapted from related published studies and those selected based on discretion. Information was collected on the sociodemographic data, injury prevalence, site, time of day, external causes / mechanism, activity when injured, severity, treatment received, and the like. The informed consent from the School and various school authorities was obtained in writing, while those of the individual students were obtained verbally. The questionnaires were self-administered, but explanations and assistance were given to those who needed it. They were collected on the spot by the researcher.

Sampling procedure

Purposive, stratified, and simple random sampling were employed in selecting the subjects. Six schools in six wards, out of 12 wards making up the Agbor Metropolis, were purposively selected, based on their strategic position and population size. These were Ward 1 (Imeobi Secondary School), Ward 2 (Gbenoba Grammar School), Ward 6 (Baptist Girls High School), Ward 8 (Mary Mount Girls College), Ward 9 (Ika Grammar School), and Ward 12 (Ogbemudia Secondary School). A sample of 386 was then stratified based on the population strength of each school, taking into consideration gender and class population differences. A simple random technique was used to select subjects from each class, based on the sample determined by stratification, starting from the first student met on entering each class.

Statistical analysis

Data generated from this study were analyzed using the Statistical Package For Social Science Students (SPSS) version 16. The association between variables was found by Chi square test of independence, with level of significance generally taken at the 0.05 level of significance.

Measures

Injury

Injury was defined as a bodily lesion that resulted in any form of treatment or led to the disruption of normal activity. Subjects who reported one or more injuries in the past one year were assumed to be injured. Each subject was asked to provide injury-related information for the single most serious injury sustained.[11]

Severity

Severity was measured on two criteria — injuries that resulted in loss of one or more days of activity, loss or absence from school, and injury that resulted in any of the following treatments, placement of a cast, stitches, use of crutches, and surgery or injury that resulted in overnight hospitalization[11,12]

RESULTS

The result was based on 386 questionnaire retrieved. Response rate was 100%. Extra data were collected to make up for a few invalid questionnaire experienced.

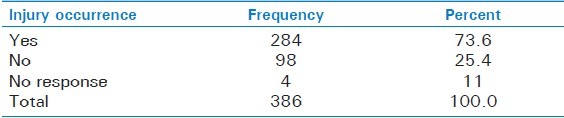

Table 1 shows that about 284 (73.6%) of respondents have experienced an injury that disrupted normal activity in the past 12 months. Of the number of injuries reported, 227 (78.3%) occurred more than once. For those who sustained injury, a mean injury frequency of 2.5 was recorded while 1.8 was recorded for all subjects.

Table 1.

Injury prevalence

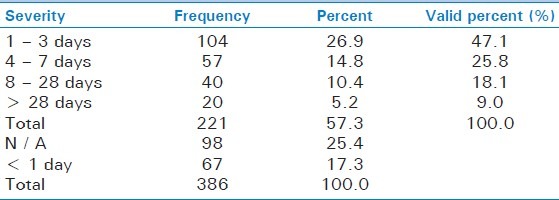

Table 2 shows that 221 (57.3%) of the injuries sustained resulted in ‘1+ days’ of activity loss with about 104 (47.1%) who reported injuries resulting in 1 – 3 days of activity loss, 25.8% in 4 – 7 days of activity loss, 18.1% in 8 – 28 days of activity loss, and 9% in > 28 days of activity loss.

Table 2.

Severity of injuries sustained (Day's activity loss)

Moreover 136 (35.2%) of the injuries required medical attention, with about 58 (15%) resulting in overnight hospitalization, 41 (10.6%) required stitching, 19 (4.9%) required placement of cast, and 18 (4.7%) required use of crutches.

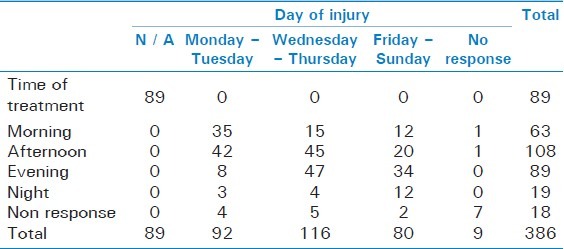

The table shows that most injuries (108 (36.4%)) occurred in the afternoon, followed by 89 (29.9%) in the evening. Wednesdays and Thursdays recorded higher number of injuries, 116 (39.1%), followed by Mondays and Tuesdays, 92 (31%), and Fridays and Sundays (26.9%). These reflected the role school-associated activities tended to play in injury occurrence. The highest number of injuries occurred on Wednesday and Thursday evenings (47) followed by Wednesday and Thursday afternoons (45).

Table 3 Shows a possible association between age and injury occurrence (P = 0.003). Injury experience tends to increase with age (64.2% for those aged 13 – 15 years, 68.9% (16 – 19 years), 88.2% (> 20 years). Although not significant (P = 0.478), male students marginally sustained higher number of injuries (71.3%) compared to females (70.5%). The type of family very significantly affected injury experience (P = 0.001), with nuclear family (84.1%) posing a higher risk compared to a polygamous family (63.1%). The level of education of the respondents’ parents tend to affect injury occurrence in the respondents i.e. the adolescents and this was stronger for female parents than for male parents. Injury occurrence was generally lower in students whose parents had a tertiary education (68% for female and 69.9% for male parents) compared to those whose parents who had just secondary education (83.9% for male and 81.8% for female parents). A very strong association tended to exist between alcohol consumption and injury experience (P = 0.001). About 59 (95.2%) of the 62 of those who consumed alcohol were injured, compared to 191 (64.7%) out 295 of those who did not. Injury severity increased consistently with the increasing number of students who consumed alcohol (P = 0.001). There was an extremely significant association between sex and injury severity (P = 0.001). Females had a higher experience of injuries that resulted in 1 – 3 days activity loss (60.7% compared to 35.2% for males), However for injuries lasting 4 – 28 days males had a higher percetnage (56.3%) than females (29.4%). Age also significantly affected the severity based on activity loss (P = 0.012). Injuries resulting in 8 – 28 days of activity loss consistently increased with age. The same applied to those resulting in > 28 days of activity loss, except in those aged 10 – 13 years. However, injuries that resulted in 4 – 7 days of activity loss consistently decreased with age.

Table 3.

Time of treatment and days of injury

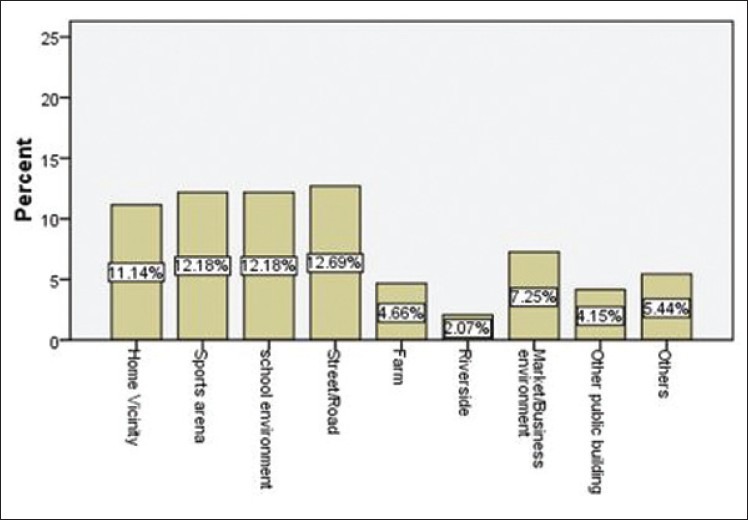

Figure 1 shows that sites reported for injury: The highest injury occurrence was street / road, 49 (12.69%), followed closely by school environment and sporting arena 47 (12.18% respectively), and then home vicinity 43 (11.14%).

Figure 1.

Injury sites

Analysis also showed that while females had higher share of injuries that occurred at home (13% compared to males, 9%), males had a higher share of injuries that occurred at the sports facility (16.8% compared to females (8%)) and on the street / road (13.5% compared to females (5%)).

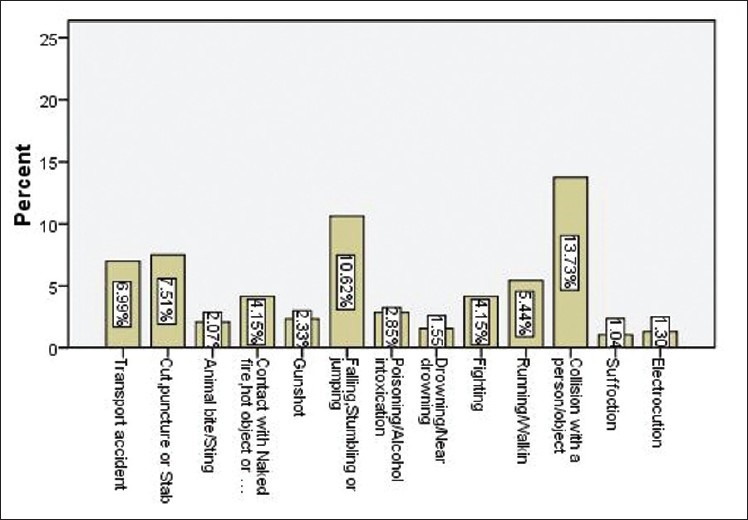

Figure 2 shows that collision with a person / object, 53 (13.73%), was the greatest mechanism followed by falling / stumbling, 41 (10.62%), cut, puncture or stabbing 29 (7.51%), and transport injury, 27 (6.99%). Note that for all key mechanisms of injuries except running / walking (female 10% compared to males 5%) males ranked higher. However, females had a higher number of non-response (21.3%) compared to males (4.3%)

Figure 2.

External causes / Mechanism of injury

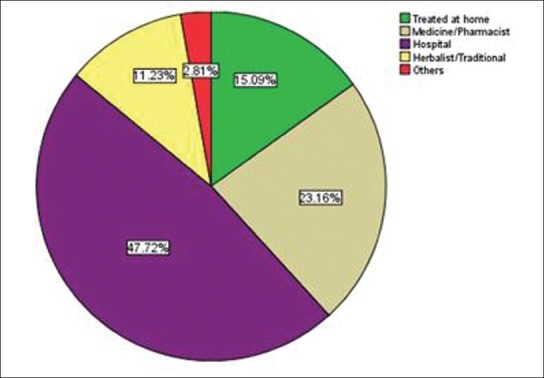

Figure 3 showed that of the reported injuries, the greater number, 136 (47.72%) received hospital treatment, followed by 66 (23.16%) who patronized medicine / pharmacists, 43 (15.09%) were treated at home by either a nurse or family member.

Figure 3.

Type of treatment received

DISCUSSION

About 284 (73.6%) of the respondents according to Table 1 have experienced an injury that disrupted normal activity in the past 12 months compared to 98 (25.4%) who did not. This prevalence was high, probably due to the broader definition used for injury. However, there was a prevalence of 70.8% in previous studies, but this was among urban children.[13] There was a tendency for multiple injuries among the respondents, with a mean frequency of 1.8% per child and 2.5% for those who sustained injury. Hence, any child that sustained an injury had a tendency to sustain approximately two other injuries by the end of the year. According to Table 2, 221 (57.3%) of the respondents sustained injuries resulting in ‘1+ days’ of activity loss, while about 136 (35.2%) sustained injuries requiring treatment. These imply absenteeism from school activity, economic loss to the family, inability to perform duties and assist parents at home, as well as removing the mother or other siblings from school or family duties, to care for the injured. These were high compared to 41.3% that reported activity loss and 13.3% that reported injuries requiring medical attention in the previous studies.[11] Plugg et al.[14] reported that 16% of injuries required medical attention. The discrepancies may be attributed to the definitions. Treatment as used in this study was not restricted to hospital or doctor's attention.

Figure 1 shows that of the injuries reported, the site with the highest injury occurrence was street / road 49, (12.69%), followed closely by school environment and sporting arena, 47 (12.18% respectively), and then home vicinity, 43 (11.14%). Similar results have been reported in the literature.[15] It is obvious that in many Nigerian urban environments, the streets constitutes a beehive of activity for adolescents; plays, fights, soccer, and so on, could all take place on the streets. This coupled with its traffic injury propensity could explain why streets / roads topped the list. School environment and sporting arenas could reflect the role and opportunities these environments could provide for injury control among young school people. Young people spent more than half of their days around the school environment, most times and in their leisure times playing games, which could be school-related. Home / yard (26.3%), sport facilities (23.4%), schools or school ground (21.8%), and street (15.8%) have been reported as high injury sites,[11] while another study reported home (41.2%) road (38.8%), And recreation / sports area (9.7%) as high injury sites.[16] Sports has been reported as the greatest causation among 18 – 24 year olds.[14] The result highlights areas or environments where injury reduction intervention among adolescents can be targeted in Nigeria and other African countries. The fact that females dominate in injury experience around the home is consistent with the fact that they are attached to the home more than males, who dominate activities in the sports arenas and streets of Nigeria. A similar result has been noted in the previous studies.[14,11]

According to Figure 2 collision with a person / object, 53 (13.73%) was the greatest mechanism followed by falling / stumbling, (10.62%), cut, puncture or stabbing, 29 (7.51%), transport crash, 27 (6.99%). Knowing what caused an injury and how the injuries were caused provide opportunities for prevention. The first two mechanisms could be related with play and sporting events usually associated with streets, school environment, sports arenas, and around the home, among adolescents. An Iranian study identified transport crash, falls, and collision as the leading causes of injury.[17] However in an injury study among adolescents and young people in four countries, ‘fall’ was the dominant mechanism, while collision ranked second in two countries.[18] Cut, puncture, and stabbing have also been prominently noticed in previous studies[19] and constitute a leading cause among males.[20] The few discrepancies in the present study may be due to environmental differences.

Figure 3 shows that of the reported injuries, a greater percentage, 43 (47.72%) received hospital treatment, followed by 66 (23.16%) that patronized medicine / pharmacists, 43 (15.09%) were treated at home, while 32 (11.23%) consulted herbalist / traditional procedures. The place where injuries were treated could play a role in recovery experiences, due to differences in expertise. Previous studies have reported a greater number (58%) of injuries as having been treated at the hospital / health center; while 3% of the treatment was by untrained traditional practitioners.[20]

According to Table 3 there was a positive association between age and injury occurrence (P = 0.003), possibly due to increasing involvement in events associated with injury as a child grows up. This was, however, in contrast with a previous study, where injury was found to decline with age among those aged between 18 and 64 years.[14] In another previous study, the injury rates were lower among older children compared to younger ones in Israel, the United States, Switzerland, and Lithuania, whereas, in Canada and Belgium the opposite trend was found, that is, rates were higher for older students than for younger ones.[11] It has been reported that injury prevalence among children does not decline with age, as even though their capacity to avoid injury increases with age, the complexity of environmental exposure also increases with age.[21,22]

Age and sex also affected injury severity (P = 0.012 and 0.000, respectively), which generally tended to increase with age, possibly due to the increasing tendency for risky activity that came with age. In relation to sex it could be a reflection of differences in behavioral tendencies. There was no significant difference between males and females in injury occurrence (P = 0.478), although males marginally experienced a greater number of injuries. The type of family very significantly affected injury experience, (P = 0.000), with the nuclear family (84.1%) posing a higher risk compared to a polygamous family (63.1%). This could suggest a higher level of freedom enjoyed by children from nuclear families, giving them more opportunities to be involved in a wide variety of activities compared to those from polygamous families, who were at most times attached to their mothers’ business. This, however was in contrast to the opinions of previous studies where children of polygamous families were found to be at a higher risk.[21,23] However, the subjects of that study were lower in age that those in this study. The parents’ level of education seemed to affect injury risk in their wards, with the relationship being stronger for female parents rather than male parents. This may be related to the dominant role and influence mothers have over the behavior and attitude of their children. Injury occurrences were generally lower in students whose parents had tertiary education. A very strong association tended to exist between alcohol consumption and injury experience (P = 0.000). About 95.2% of those who consumed alcohol were injured compared to 64.7% of those who did not. The presence of alcohol in the body at the time of injury could also be associated with a greater severity of injury and less positive outcomes.[14,24,25]

The table shows that most injuries occurred in the afternoon (36.4%) followed by evening (29.9%). — Wednesdays and Thursdays recorded a higher number of injuries, followed by Mondays and Tuesdays (31%) and then Fridays and Sundays (26.9%). These reflected the role school-associated activities played in injury occurrence. Most times, games and manual labor were scheduled on Wednesdays and Thursdays, and their period almost always coincided with or lasted till the afternoon periods. Sometimes students engage in injury-prone activities as they return home in the afternoons. Sometimes also games, fetching of water, and other home activities were done in the evenings, making this period also prone to injury. Weekends were less prone to injuries as adolescents tended to be confined at home assisting parents or engaged in less injury-prone, religious activities. Some researchers reported a higher occurrence of injuries during late afternoons and early evenings.[21,26,27]

CONCLUSION

The study indicated relatively high injury prevalence among the respondents. It highlighted the need to pay particular attention to injuries resulting from collision, falls, and sharp objects, which were the three top mechanisms of injuries according to this study. Interventions should focus, among other targets, streets / roads, sport arenas, and school compounds, with the aim of reducing injury-prone factors in these areas.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peden M, Scurfield R, Sleet D, Mohan D, Hyder AA, Jarawan E, et al. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Last accessed on Oct 2010]. World report on road traffic injury prevention; p. 3. Available from: http://www.who.int/worldhealth-day/2004/infomaterials/world_report/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon S, Barss S, Barss P. Untintentional Injuries in Developing Countries. The Epidemiology of a neglected Problem. [Last retrieved on 2011 Jan 23];Epidemiol Rev. 1991 13:228–66. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036070. Available from: http://www.epirevoxfordjournals.org . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frenk J, Bobadilla JL, Sepulveda J, Cervantes ML. Health Transition in Middle Income Countries: New challenges for health Care. Health Policy Plan. 1989;4:29–39. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barss PG. Doctorial dissertation. Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health; 1991. Health Impact Of Injuries in the highlands of Papua New Guinea: A verbal autopsy study. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivara FP, Grossman DC, Cummings P. Injury prevention. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:543–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708213370807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hang HM, Ekman R, Back TT, Byass P, Svantrom L. Community based assessment of unintentional injuries.A pilot study in rural Vietnam. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2003;62:38–44. doi: 10.1080/14034950310015095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norton R, Hyder AA, Bishai D, Peden M. Unintentional Injuries. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. [Last Retrieved on 2011]. pp. 737–750. Available from: http://Worldbank.org/HEALTHNUTRITION AND POPULATION/RESOURCES/281627-1114107818507injurycontrol.pdf .

- 8.AIHW, Moller J. Injury among 15 to 19 year old males. Canberra: AIHW; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mock CN, Boland E, Acheampong F, Adjei S. Long term injury-related disability in Ghana. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:732–41. doi: 10.1080/0963828031000090524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krug EG, Dawlberg LL, Mercy JA. World report on violence and health. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molcho M, Harel Y, Pickett W, Scheldt J, Mazur MD, Overpeck PC. The epidemiology of non-fatal injuries among 11, 13 and 15-year old youth in 11 countries: Findings from the 1998 WHO-HBSC cross national survey. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2006;13:205–11. doi: 10.1080/17457300600864421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overpeck MD, Kotch JB. The effect of US children's access to care on medical attention for injuries. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:402–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.3.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang HC, Stallones L, Keefe TJ. Childhood Injury deaths.Rural urban differences, Colarodo 1980-8. Inj Prev. 1997;3:35–7. doi: 10.1136/ip.3.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plugg E, Steward-Brown S, Knight M, Fletcher L. Injury Morbidity in 18-64-year-old: Impact and Risk factors. J Public Health Med. 2002;24:27–33. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/24.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AIHW, Eldridge D. AIHW bulletin series no. 60.Cat. no. AUS 102. Canberra: AIHW; 2008. Injury among young Australians. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moshiro C, Heuch I, Astrom AN, Setel P, Hemed Y, Kwale G. Injury Morbidity in an Urban and rural area in Tanzania; an epidemiological survey. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soori H, Akbari ME, Ainy E, Zali AR, Naghavi M, Shiva N. Epidemiological pattern of non-fatal Injuries in Iran. Pak J Med Sci. 2010;26:206–11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bangdiwala S, Arizola-Perez E, Romer CC, Schmidt B, Valdez-Lazo F, d’Suze C. Incidence of Injury in Young People: Methodology and Results of a Collaborative Study in Brazil, Chile, Cuba and Venezuala. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19:115–24. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobusingye O, Guwatudde D, Let R. Injury Patterns in rural and Urban Uganda. Inj Prev. 2001;7:46–50. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omoniyi OA, Owoaje ET. Incidence and Patterns of Injuries among residence of a rural area in South-Western Nigeria. [Last retrieved on March 2011];BMC Public Health. 2007 7:246. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-246. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartlett SN. The problem of children's injury in low – income countries: A review. Health Policy Plan. 2002;17:1–13. doi: 10.1093/heapol/17.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan JR, Valdes-Lazo F. Injurys in Childhood and adolescence: The role of research. In: Manciaux M, Romer CJ, editors. Injurys in Childhood and adolescence. Geneva: WHO; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmed MK, Rahman M, Van Ginnekem J. Epidemiology of Child deaths due to Drowning in Matlab, Bangladesh. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:306–11. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rehn J, Taylor B, Patra J. Volume of alcohol consumption, pattern of drinking and burden of disease in the European region 2002. Addiction. 2006;101:1086–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glucksman C. Alcohol and Injurys. Br Med Bull. 1994;56:76–84. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bass D, Albertyn R, Melis J. Child Pedestrian Injuries In the Cae Metropolitan area-Final results of a hospital based Study. S Afr Med J. 1998;85:96–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janson S, Aleco M, Beetar A, Bodin A, Shami S. Injury's risks for suburban Preschool Jordanian Children. J Trop Pediatr. 1994;40:88–93. doi: 10.1093/tropej/40.2.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]