Abstract

Alopecia is a rare manifestation of Hodgkin's disease. It may be due to follicular destruction due to direct infiltration by the disease, or it may be a secondary or paraneoplastic manifestation. In this patient, hair loss, diffuse yperpigmentation, and generalized itching preceded other manifestations of the disease. The pattern of hair loss was diffuse and generalized in nature involving scalp, eyebrows, axilla, and groin. Subsequently, the patient was diagnosed to be a case of Hodgkin's lymphoma, based on clinical and histopathological features. Earlier reports on alopecia accompanying Hodgkin's disease have also been discussed. This case highlights the importance of keeping a high suspicion of an underlying malignancy in patients presenting with such cutaneous manifestations.

Keywords: Alopecia, Hodgkin's disease, paraneoplastic

INTRODUCTION

Hodgkin's disease is a lymphoproliferative malignant disorder presenting as painless lymph node swellings. Direct skin involvement is rare, usually occurring in the setting of advanced nodal or visceral disease.[1,2] Associated skin lesions are seen in 17% to 53% of patients, that are usually paraneoplastic findings rather than cutaneous infiltration of the tumor.[3,4] Paraneoplastic involvement may be in the form of pruritus, urticaria, erythroderma, hyperpigmentation, and erythema nodosum. Direct infiltration may give rise to nodules, ulcers, plaques, or tumors. Alopecia may represent either of the two forms of skin involvement. In this case of Hodgkin's disease, the patient presented with severe pruritus, diffuse hyperpigmentation, and generalized hair loss much before the disease symptoms per se. This was a heralding sign of serious underlying malignant disorder.

CASE REPORT

A 30-year-old female presented with 6 months history of generalized itching, diffuse hair loss, and progressive darkening of skin all over the body. Itching was associated with excoriation that healed by scarring. Within 2 months, she also developed dry cough, intermittent high grade fever, and progressive loss of weight and appetite. She also noticed multiple, painless swellings of varying sizes in the neck, axilla, and groin for the last 15 days. There was no history of skin eruptions, hemoptysis, breathlessness, joint pain, oral ulcerations, photosensitivity, menstrual abnormalities, or fetal loss. No past history of tuberculosis or any similar complaints in the patient or another family member was present. History of chronic drug intake for any illness was insignificant. General examination [Figure 1] revealed pallor, diffuse hyperpigmentation, and generalized hair loss with non-scarring alopecia. She also had generalized lymphadenopathy; the nodes being mobile, firm, discrete, and non-tender. Only significant systemic finding was the presence of hepatomegaly, with liver span being 18 cm. The hematological profile revealed normal complete blood count and kidney function tests. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was raised (43 mm/h) and hypoalbuminemia (27 g/L) was present. Serum iron, total iron binding capacity, vitamin B12, and folate levels were normal. Viral markers (HIV, HbSAg, and anti HCV), antinuclear antibodies, and anti-double stranded DNA antibodies were negative. Thyroid profile, fasting serum cortisol, serum testosterone, and serum zinc level were normal. Bone marrow aspiration revealed hypercellular marrow with the myeloid:erythroid ratio being 5:1. No marrow infiltration by atypical cells was present. Contrast-enhanced computerised tomography (CECT) of abdomen [Figure 2] revealed hepatomegaly, multiple enlarged mesenteric, pre-para aortic, retrocrural, bilateral inguinal, and bilateral iliac lymph nodes. Spenic involvement was in the form of multiple subcentimeric hypodense, homogenous, soft tissue density nodules. CECT of thorax [Figure 3] revealed bilateral pleural effusion (left > right) with subsegmental passive atelectasis of lower lobe of left lung. Multiple enlarged heterogeneous pre-paratracheal, paraesophageal, aortopulmonary, subcarinal, and bilateral supraclavicular lymphnodes were noted, largest one measuring 2.5 cm in diameter. MRI brain was normal. Histopathological examination of the lymph node biopsy revealed partial effacement of lymphoid architecture with dilated sinuses. Polymorphous lymphoid infiltrates with fair number of eosinophils were seen in the background. Few large hystiocytoid cells with prominent vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli, resembling variant Reed-Sternberg cells [Figures 4 and 5] were present. Immunohistochemistry revealed strong positivity for CD 30 [Figure 6] and CD 45. Subsequently, a diagnosis of Hodgkin's lymphoma was made. She was started on ABVD (Adriamycin, Bleomycin, Vinblastine, Dacarbazine) regimen and on follow-up after first cycle, significant clinical improvement was noticed. Clinical examination did not reveal any lymph nodes, hepatomegaly, or pleural effusion.

Figure 1.

Patient in the left panel before illness and in the right panel showing diffuse hair loss and hyperpigmentation

Figure 2.

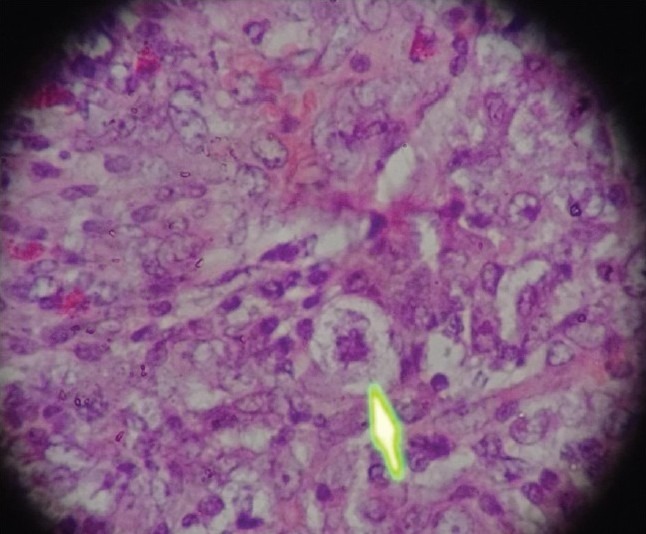

High magnification microscopy of the axillary lymph node showing a histiocytoid cell with prominent nuclei and nucleoli (arrow) representing variant Reed–Sternberg (RS) cell (H and E, 40×)

Figure 3.

CECT thorax showing left-sided pleural effusion and multiple para-tracheal lymph nodes

Figure 4.

CECT abdomen showing hepatomegaly and multiple hypoechoic areas in spleen suggesting splenic involvement

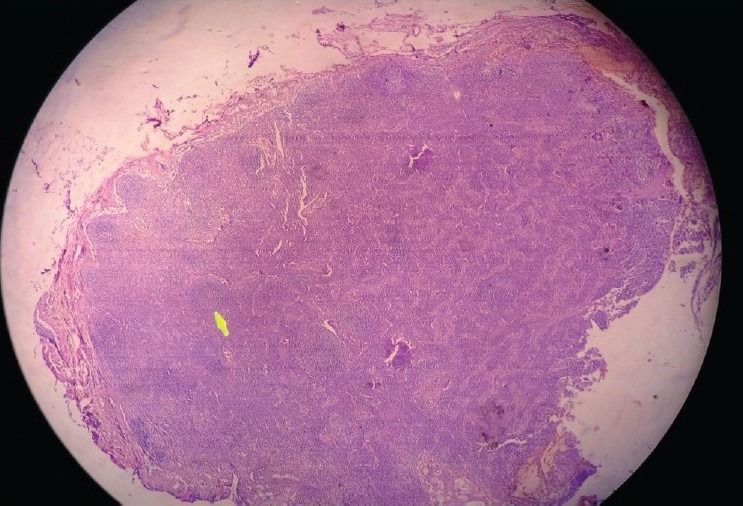

Figure 5.

Low magnification microscopy of an axillary lymph node showing effacement of lymph node architecture with a preserved lymphoid follicle (arrow) (H and E, 10×)

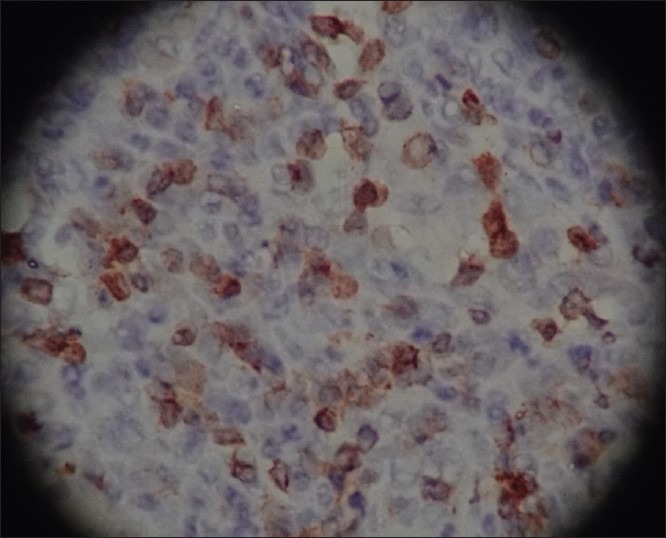

Figure 6.

High power microscopy showing CD30 positivity on immunohistochemistry for RS cells (brown areas) (H and E, 40×)

DISCUSSION

Hair loss in Hodgkin's disease (HD) can be non-specific (paraneoplastic) or specific. The former is more common and a diverse variety of hair loss patterns has been seen. It can be due to direct follicular infiltration and destruction by lymphomatous cells.[5] Alopecia may also be caused by excessive scratching to relieve itching. Other causes may be an associated icthyosiform atrophy or endocrine dysfunction secondary to pituitary or adrenal infiltration. A similar case was reported by Cannon, in which there was alopecia of scalp with loss of pubic and axillary hair and loss of lateral eyebrows.[6] Similarly, a case of alopecia of scalp followed by total body alopecia was reported by Jones and Alden.[7] Cases of alopecia areata and telogen effluvium occurring concomitantly with Hodgkin's disease have been reported.[3,8,9]

Pruritus is seen in 10–25% of the cases, and may even precede the diagnosis of lymphoma.[10] It is characterized by burning and intense itching, usually on the lower limbs and can become generalized. It alone is not a prognostic marker of lymphoma, but may become so if associated with other systemic signs. The hypothesized mechanism is the stimulation of free nerve endings at the dermo-epidermal junction by histamine, enkephalins, and prostaglandins.[11] Hyperpigmentation in Hodgkin's disease is usually localized to flexural areas and nipples. It is akin to Addisonian pigmentation and is melanin in origin, but mucous membranes are usually spared.

In our case, pruritus and hyperpigmentation was generalized along with diffuse hair loss involving scalp, lateral eyebrows, axilla, and groin. After ruling out the other causes of alopecia by extensive investigations, it could definitely be attributed to the underlying lymphoproliferative condition that the patient was suffering from. This highlights the importance of alopecia as a heralding sign of a serious underlying systemic illness.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors mentioned in the manuscript.

Manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors.

Requirements for authorship as stated in the guidelines have been met by each author.

Each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaw MT, Jacobs SR. Cutaneous Hodgkin's disease in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Cancer. 1989;64:2585–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19891215)64:12<2585::aid-cncr2820641229>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White RM, Patterson JW. Cutaneous involvement in Hodgkin's disease. Cancer. 1985;55:1136–45. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850301)55:5<1136::aid-cncr2820550532>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shelmire B. Hodgkin's disease of the skin. South Med J. 1925;18:511–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barron M. Unique features of Hodgkin's disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1926;2:659–90. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Primary Hodgkin's disease of the scalp, Society Transactions. Arch Derm Syph. 1950;62:759–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon AB. Practical points on the diagnosis and treatment of the so-called lymphoblastoma group of diseases. J Med Assoc State Ala. 1932;1:454–67. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones JW, Alden HS. Generalized lymphogranulomatosis of the skin: Report of a case in a Negro. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1929;20:212–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan PD, Berk MA, Kucuk O, Singh S. Simultaneously occurring alopecia areata and Hodgkin's lymphoma: Complete remission of both diseases with MOPP/ABV chemotherapy. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1992;20:345–8. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950200416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein AW, Rudolph RI, Leyden JJ. Telogen effluvium as a sign of Hodgkin disease. Arch dermatol. 1973;108:702–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan HS. Hodgkin's disease. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lydon J, Purl S, Goodman M. Integumentary and mucous membrane alterations. In: Groenwald SL, Frogge MH, Goodman M, Yarbro CH, editors. Cancer Nursing: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. Boston, Mass: Jones and Bartlett; 1990. pp. 594–635. [Google Scholar]