Abstract

We report a series of four patients who presented with complaints of diffuse non-scarring alopecia. They had similar clinical features of alopecia, hyperseborrhea, and distinct keratinaceous hair casts that encircled the hair shafts. Propionibacterium acnes was isolated from two of the patients’ scalp, and Gram-positive, Giemsa-positive bacteria were seen in the hair follicles in the scalp biopsy of one of the patients. The patients’ symptoms did not respond to standard treatment for seborrheic dermatitis, but responded to a course of systemic antibiotics targeting P. acnes. We propose a role for P. acnes colonization of the terminal hair follicles in the pathogenesis of hair casts, and possibly diffuse non-scarring alopecia. Possible mechanisms of pathogenesis are discussed with a literature review.

Keywords: Hair casts, non-scarring alopecia, Propionibacterium acnes, systemic antibiotics

INTRODUCTION

Hair casts are rarely reported entities, and do not receive much attention in most dermatological textbooks. Most reports and case series were published before 1990, and link them to either abnormal keratinization of the scalp, or with traction forces applied to the hair follicle. Here, we describe four cases of hair casts with a putative link to Propionibacterium acnes.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 32-year-old Chinese man presented for scalp flakiness and greasiness for a week. He had difficulty removing them despite washing his hair with commercial anti-dandruff shampoos. There was also an increase in hair loss occurring at the same time as the onset of the flaky scalp.

On examination, there was a mild diffuse sparsity of scalp hairs affecting the entire scalp. Numerous greasy, tubular yellowish hair casts coated the hair shaft in a beaded fashion [Figure 1a and b]. These hair casts could be moved along the hair shaft when grasped between the fingers. Hair pull test was positive, and revealed the same greasy, hyperkeratotic material at the end of the hair root. Hair microscopy confirmed that these greasy concretions encased the hair shafts [Figure 1c]. Hair microscopy was negative for fungal elements and nits. Culture of the casts yielded P. acnes.

Figure 1.

(a) Patient 1 with significant hair casts and diffuse alopecia; (b) Significant hair casts in Patient 1; (c) Keratotic material encasing the hair shaft in a beaded fashion, Light microscopy ×100; (d) Significant clearance of hair casts in Patient 1 after treatment with Doxycycline

Initial treatment with Betamethasone scalp lotion and selenium sulfide shampoo for one month was ineffective. After the positive result of P. acnes culture was obtained, he consented to a trial of erythromycin ethylsuccinate (EES) 400 mg twice daily for one month. He noticed less hair casts in the first three weeks of treatment, but recurred upon the last week. He was then prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily as monotherapy, without any topical medications. All hair casts cleared by the end of six weeks of doxycycline, but recurred four weeks after discontinuation of the antibiotic. The patient subsequently developed acne vulgaris over the face and chest. Treatment with a repeat course of doxycycline cleared both the acne and hair casts [Figure 1d].

Case 2

A 22-year-old Chinese man presented with a single localized patch of alopecia areata on the scalp, and extensive “dandruff.” He had previously had another episode of alopecia areata with complete hair regrowth two years prior.

On examination, there were greasy, scaly, hair casts that coated the hair shaft in a beaded fashion [Figure 2a]. There was a 1.5-cm diameter patch of non-scarring alopecia on the scalp.

Figure 2.

(a) Hair casts noted in Patient 2; (b) Clearance of hair casts in Patient 2 after 2 weeks of Doxycycline

He was treated with monthly intralesional steroids and minoxidil 5% lotion for the alopecia areata, with complete regrowth of hairs within the bald patch after four months. Despite resolution of the alopecia areata, he continued to have numerous hair casts along the hair shafts of his scalp, and a mild diffuse alopecia.

Pyogenic cultures of the casts were negative, but culture media specific for P. acnes was not used at the time. Hair microscopy, scrapings, and cultures were negative for fungal elements.

Various treatments including clobetasol shampoo, ciclopirox shampoo, and betamethasone scalp lotion yielded no improvement to the hair casts.

He was subsequently prescribed EES 800 mg twice daily as monotherapy, with significant reduction in hair casts within two weeks [Figure 2b]. He was not on any other topical medications at that time. The EES dose was reduced to 400 mg twice daily and subsequently 400 mg once daily over the next four months. He continued to have significant reduction in hair cast during the course of treatment. He also noticed a decrease in hair loss numbers as the hair casts decreased.

Case 3

A 25-year-old Chinese lady presented with gradual hair loss over one year, losing more than 100 strands per day. Her general health was good and menstrual cycles were regular. Thyroid function test, ferritin and hemoglobin levels were normal.

On examination, there was minimal diffuse sparsity of the scalp. Notably, there were hair casts along the hair shaft in a beaded fashion. Hair pull test was negative.

Culture of the hair casts yielded P. acnes.

She was initially prescribed minoxidil 2% lotion twice daily to the scalp, with no improvement of hair loss. She was also treated with selenium sulfide shampoo, betamethasone scalp lotion, and ketoconazole shampoo, with no improvement to the hair casts. She was subsequently prescribed EES 400 mg twice daily with clearance of hair casts after a four-week course. However, hair casts recurred a month after EES was stopped. A repeat course of EES for four weeks resulted in reduction of hair casts again. The patient also reported that hair loss numbers had also decreased while on the oral antibiotic.

Case 4

A 25-year-old Chinese lady presented with one year of worsening “dandruff” and increased hair loss over the last six months. She was noted to have hair casts and mild diffuse sparsity of her hair [Figure 3]. Hair pull test was also positive. A scalp biopsy was performed, which showed intact follicular units with minimal inflammation, and Gram-positive, Giemsa-positive cocci in the follicular canals, consistent with P. acnes [Figure 4a–d]. One fungal culture yielded Microsporum canis, which was likely a contaminant as fungal elements were not seen on scalp biopsy or hair microscopy, and all subsequent fungal cultures were negative without specific anti-fungal therapy.

Figure 3.

Hair casts along the hair shafts of Patient 4

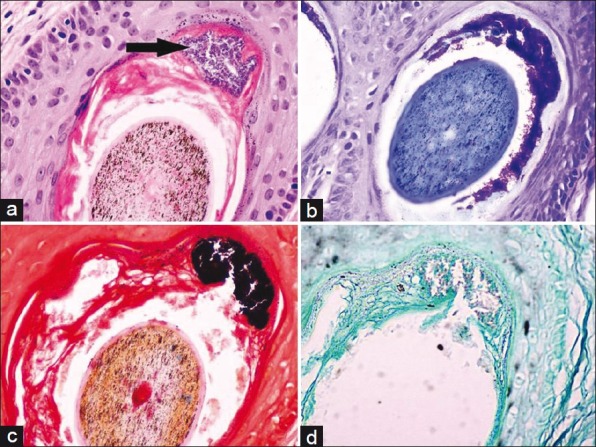

Figure 4.

(a) Hair follicle at the level of the isthmus showing hyperkeratinization within the follicular canal, encircling the hair shaft. There is a foci of bacterial cocci (arrow). The bacterial coccal colonies stain positively with (b) Giemsa stain and (c) Gram stain (d) The bacteria stain negatively with GMS stain, ×400

She was prescribed EES, and her hair casts and alopecia resolved in four months. Two months after cessation of antibiotics, the hair casts recurred, and this was again successfully treated within 1 month of restarting EES.

DISCUSSION

Hair casts are cylindrical structures that encircle the hair shaft (peripilar) and can be freely moved up and down the shaft. This entity was first described by Kligman in 1957, who described the casts as “parakeratotic comedones of the scalp.”[1] Subsequently, the literature describes hair casts in two main groups of patients: those with a hyperkeratotic scalp condition (for example, psoriasis,[2] seborrheic dermatitis,[3] or lichen planus) and those who have subjected their hair to continuous traction forces (like tying of hairs in tight pony-tails[4] or braids). Interestingly, hair casts are not a feature of trichotillomania, where the traction forces on the hair are forceful and intermittent.[5,6] Hair casts have also been referred to as “pseudonits” as they have been misdiagnosed as pediculosis capitis in school-going children. Unlike nits that are firmly adherent to the hair shaft, hair casts can be moved up and down the shaft like beads on a string.

According to a proposed classification by Scott and Roenigk,[7] they can be classified into keratin or non-keratin casts. Peripilar keratin casts (PKC) are composed of either inner root sheath keratins, outer root sheath keratins, or a combination of both (compound PKC). Non-keratin casts may be mycotic, bacterial, or artefactual.

P. acnes is a Gram-positive aerotolerant, anaerobic bacillus that produces propionic acid as a metabolic byproduct. It is ubiquitous in sebaceous glands of human beings, and derives energy from fatty acids found in sebum. It has been linked to the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris, folliculitis, and rarely systemic infections complicated by endocarditis or SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis).[8]

Our patients presented with hair casts and diffuse alopecia, with two patients demonstrating presence of P. acnes in the culture of hair casts. The hair casts and alopecia also resolved following treatment with antibiotics against P. acnes in all cases. Although Case 2 had alopecia areata, we believe that the mild diffuse hair loss he experienced was of a different etiology and likely associated with the hair casts, and not diffuse alopecia areata. This is supported by the improvement of the diffuse hair loss in line with decrease of his hair casts with antibiotic treatment. We propose a role for P. acnes in the pathogenesis of hair casts.

The isolation of P. acnes requires special culture medium such as Reinforced Clostridial agar or Mueller-Hinton agar, and the bacteria do not grow well on routine aerobic or anaerobic bacterial culture media. Furthermore, P. acnes requires special conditions (anaerobic, with temperatures just below 37°C) for optimal growth. This may explain the negative bacterial culture results in cases 2 and 4, even though case 4 showed P. acnes colonies on biopsy, as only routine culture media were used.

Hyperkeratinization

P. acnes has been implicated in the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris, a disorder of the pilosebaceous unit, by way of maintaining the inflammation of the comedones. It may also contribute to the process of hyperkeratinization of the hair follicle in the production of hair casts. P. acnes has also been associated with hyperkeratotic follicular spicules on the neck that cultured positively for P. acnes had resolved treatment with oral erythromycin.[9]

Loss of the b1-integrin from basal keratinocytes has been associated with reduction in basal proliferation in vivo.[10] Jarousse et al. went on to demonstrate that P. acnes extracts could induce an increase in b1-integrin expression in keratinocyte explants in vitro, as well as an increase in the expression of filaggrin in differentiated keratinocytes.[11] Although this study was performed on skin from discarded abdominoplasties, the findings could be extrapolated to suggest a stimulatory role for P. acnes in keratinization of sebaceous skin.

Hyperseborrhea

Another feature our patients had in common was the greasiness and flakiness of their scalp, for which they all received standard treatment for seborrheic dermatitis. Selenium sulfide, ketoconazole, and ciclopirox shampoos were ineffective in our patients, but systemic antibiotic treatment was successful in reducing this symptom.

Iinuma et al. addressed this in an experiment whereby they showed that six different strains of P. acnes were able to induce lipogenesis in hamster sebocytes, leading to increased sebum secretion.[12] This has been attributed in part to the stimulation of the peroxisome proliferation-activating receptors by prostaglandins by P. acnes products.[13]

This effect of P. acnes on sebaceous glands, in addition to hyperkeratinization of the hair follicle, may contribute to the pathogenesis of the greasy hair casts. The excess material from the pilosebaceous unit may accumulate to form excrescences that coat the hair shaft.

Alopecia

All our patients experienced alopecia, with positive hair pull test on examination. Although one patient (Case 2) had a history of alopecia areata, this had resolved by the time the diagnosis of hair casts was made. Patients with seborrheic dermatitis rarely experience alopecia.

Before its genome was sequenced in 2005, P. acnes was thought to be a ubiquitous commensal of the skin.[14] Even its role in the pathogenesis of acne was tentative. With information from its genome, mechanisms by which P. acnes colonizes and causes local tissue destruction are better understood. For example, P. acnes synthesizes many enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix (hyaluronate lyase) and cornified envelope (endoglycoceramidases, sialidase), heat-shock proteins that activate the innate immune system (GroEL, DnaK), and other enzymes involved in the metabolism of porphyrins. Porphyrins released from P. acnes are activated by ultraviolet light to produce reactive oxygen species, which in turn may contribute to follicular inflammation via the complement cascade. Interestingly, porphyrins and C3 in the pilosebaceous canal were more frequently associated with patients with androgenetic alopecia than in controls,[15] suggesting it may play a role in alopecia.

Differential diagnoses

Our patients had a distinct hyperkeratotic disorder of the terminal hair follicles of the scalp, resulting in the formation of hair casts and alopecia. The consistent occurrence of P. acnes in cultures from these hair casts, coupled with clearance of hair casts and improvement of alopecia upon treatment with antibiotics against P. acnes suggests that the bacteria is directly involved in the pathogenesis of this condition.

This condition is distinct from seborrheic dermatitis as the latter presents with flakes of skin that do not encircle the hair shaft in a beaded fashion. Hair pull in seborrheic dermatitis is also frequently negative. Our patients were given topical steroid lotion and medicated shampoos used in the routine treatment of seborrheic dermatitis, with no improvement in the hair casts. As for other conditions that might present with hair casts, our patients did not have a history of tying or braiding their hair, had no psoriatic plaques, and had no scarring of the scalp as seen in lichen planopilaris. Hair microscopy, fungal scrapes, and cultures were also negative, ruling out nits, white piedra, and other dermatophytoses.

Although all four patients responded to a course of antibiotics commonly used in the treatment of acne vulgaris, the mechanism by which the drugs took effect is not clear. As in acne vulgaris, the anti-inflammatory properties of the antibiotics might be as significant as their bacteriostatic properties.

We propose role of P. acnes in the pathogenesis of both hair casts and alopecia. A prospective study of similar cases would be helpful in its further characterization. Cases with a similar presentation would benefit from a trial of oral doxycycline or erythromycin to arrest the potentially distressing symptom of alopecia.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kligman AM. Hair casts: Parakeratotic comedones of the scalp. Arch Dermatol. 1957;75:509–11. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1957.01550160035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keipert JA. Peripilar keratin casts in boys. Med J Aust. 1975;2:275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawber RPR. Hair casts. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100:417–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1979.tb01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rollins TG. Traction folliculitis with hair casts and alopecia. Am J Dis Child. 1961;101:639–40. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1961.04020060097013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tosti A. Trichotillomania. In: Tosti A, editor. Dermoscopy of Hair and Scalp Disorders: Pathological and Clinical Correlations. London: Informa Healthcare; 2007. pp. 92–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tosti A, Miteva M, Torres F, Vincenzi C, Romanelli P. Hair casts are a dermoscopic clue for the diagnosis of traction alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1353–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott MJ, Roenigk HH. Hair casts: Classification, staining characteristics and differential diagnois. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:27–32. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaeverbeke T, Lequen L, De Barbeyrac B, Labbé L, Bébéar CM, Morrier Y, et al. Propionibacterium acnes isolated from synovial tissue and fluid in a patient with oligoarthritis association with acne and pustulosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1889–93. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199810)41:10<1889::AID-ART23>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chia HY, Tay HL, Lee JSS. Hyperkeratotic follicular spicules associated with Propionibacterium acnes with response to topical Erythromycin. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00979.x. doi: 101111/j1346-8138201101472x (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brakebusch C, Fassler R. b1 integrain function in vivo: Adehesion, migration and more. Cancer Metastasis Reviews. 2005;24:403–11. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-5132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarrouse V, Castex-Rizzi N, Khammari A. Modulation of integrins and filaggrin expression by Propionibacterium acnes extracts on keratinocytes. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;299:441–7. doi: 10.1007/s00403-007-0774-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iinuma K, Sato T, Akimoto N. Involvement of Propionibacterim acnes in the augmentation of lipogenesis in hamster sebaceous glands in vivo and in vitro. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2113–9. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwata C, Akimoto N, Sato T. Augmentation of lipogenesis by 15 deoxy-Ä12,14 -prostaglandin J2 in hamster sebaceous glands: Identification of cytochrome P450-mediated by 15 deoxy-Ä12,14 -prostaglandin J2 production. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:865–72. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brüggerman H. Insights in the pathogenic potential of Propionibacterium acnes from its complete genome. Cutan Med Surg. 2005;24:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young JW, Conte ET, Leavitt ML, Nafz MA, Scroeter AL. Cutaneous immunopathology of androgenetic alopecia. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1991;91:765–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]