Abstract

This study evaluated the quality and bacteriologic safety of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) produced by 3 simple, inexpensive tube centrifugation methods and a commercial system. Citrated equine blood collected from 26 normal horses was processed by 4 methods: blood collection tubes centrifuged at 1200 and 2000 × g, 50-mL conical tube, and a commercial system. White blood cell (WBC), red blood cell (RBC), and platelet counts and mean platelet volume (MPV) were determined for whole blood and PRP, and aerobic and anaerobic cultures were performed. Mean platelet concentrations ranged from 1.55- to 2.58-fold. The conical method yielded the most samples with platelet concentrations greater than 2.5-fold and within the clinically acceptable range of > 250 000 platelets/λL. White blood cell counts were lowest with the commercial system and unacceptably high with the blood collection tubes. The conical tube method may offer an economically feasible and comparatively safe alternative to commercial PRP production systems.

Résumé

Centrifugation en tube pour le traitement du plasma riche en plaquettes chez le cheval. Cette étude a évalué la qualité et l’innocuité bactériologique du plasma riche en plaquettes (PRP) produit par 3 méthodes simples et économiques de centrifugation en tube et un système commercial. Du sang équin citraté prélevé de 26 chevaux normaux a été traité à l’aide de 4 méthodes : des tubes de prélèvement du sang centrifugés à 1200 et à 2000 × g, un tube conique de 50 ml et un système commercial. La numération des globules blancs, des globules rouges et des plaquettes ainsi que le volume moyen des plaquettes ont été déterminés pour le sang total et le PRP et des cultures bactériennes en aérobiose et en anaérobiose ont été réalisées. Les concentrations moyennes des plaquettes s’échelonnaient d’un ordre de grandeur variant de 1,55 à 2,58. La méthode conique a donné le plus d’échantillons avec des concentrations de plaquettes supérieures à un ordre de 2,5 et dans la fourchette cliniquement acceptable de > 250 000 plaquettes/μL. La numération des globules blancs était la plus basse avec le système commercial et était trop élevée par la méthode avec les tubes de prélèvement du sang. La méthode du tube conique peut offrir une méthode de remplacement abordable et d’innocuité comparable aux systèmes de production commerciaux de PRP.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Introduction

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is a blood product made by concentrating platelets in a small volume of plasma and is used for a wide variety of applications (1–3). In equine practice, PRP has gained popularity for the treatment of wounds and tendon and ligament injuries (4–7). The mechanism of action of PRP is unknown; however, the release of high concentrations of growth factors from platelet alpha granules as platelets degranulate is believed to play a critical role (8,9). Alpha granules contain several growth factors known to have beneficial effects on tissue healing, including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor β-1, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and insulin-like growth factor-I (4,10,11).

In vitro and in vivo studies investigating the effects of PRP on healing collagenous tissues in horses are limited (4,7,12–14). Treatment of equine distal limb wounds with PRP has shown variable results from improved healing through the promotion of cell differentiation and the formation of organized collagen (7,12) to the stimulation of excessive granulation tissue and delayed wound healing (13). Treatment of superficial digital flexor tendon explants with PRP showed enhanced tendon matrix gene expression (4). In surgically created superficial digital flexor tendon lesions, PRP resulted in higher strength at failure and improved collagen fiber organization and biochemical properties (6). Two small clinical case series of horses treated with PRP showed promising results for treating tendon and ligament injuries (5,15).

A number of commercial systems are available that result in platelet products with a wide range of platelet and WBC concentrations. There is limited information available regarding the optimal platelet and WBC content necessary to achieve a desired biologic effect and it may be that specific products are better for certain applications (10,16–18). Both fold changes in platelet numbers compared with whole blood, and absolute platelet numbers are used for determining adequacy of platelet concentration (9). Without measuring growth factor levels in individual samples, platelet numbers are the best estimate of the growth factor levels expected within a tissue following platelet degranulation (19–21).

There is no single definition of PRP in the human or veterinary literature and “PRP” products include wide ranges of platelet and WBC concentrations that reflect the various separation methods and the lack of consensus on specific composition of the final product. Platelet numbers are the primary concern, but optimal WBC concentrations in PRP is a topic of discussion (17,18,22). The presence of WBCs in stored human platelet concentrates has been associated with post-transfusion complications such as febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions due to the accumulation of inflammatory cytokines (23,24). Prestorage leukocyte removal prevents increasing cytokine levels (25,26). How this information may apply to equine applications of PRP is not known; however, consideration must be given to avoiding excessive WBC concentrations in PRP for clinical applications.

Platelet concentrations in PRP commonly range from a 3- to 5-fold increase over whole blood or a minimum concentration of 300 000 to 1 000 000 platelets/μL (8,27–29). These values proposed for human PRP are educated estimations from the limited data available in vitro and in vivo (9,30). More recently, some studies suggest that high platelet numbers are no better than moderate numbers or may actually have detrimental effects (31,32). Proposed minimum platelet numbers for equine PRP have been extrapolated from the human literature. Key species differences in average platelet counts and platelet physiology between humans and horses preclude an accurate extrapolation from the human literature (33,34). Equine platelet counts are amongst the lowest reported for mammals (33). The average platelet count for humans is 200 000/μL (9) compared with 142 000/μL for horses (33). Because of these species differences, there are no established cut-off values for platelet numbers in equine PRP, merely suggested values.

The final platelet and WBC concentration in PRP is dependent on the method of preparation and the original platelet concentration in whole blood. Methods of PRP preparation include apheresis, fully automated systems, and centrifugation using commercial systems or blood collection tubes (10,35,36). Apheresis and automated methods are relatively closed systems that minimize operator error, have high repeatability, yield consistently high platelet concentrations, and have a low risk of contamination (4,10,18); however, they require expensive specialized equipment and disposables. Commercial tube centrifugation systems provide a means of processing PRP with minimal manipulation and a relatively low risk of contamination; however, the equipment and disposables are also expensive and can achieve inconsistent platelet yields as a result of operator error (18).

Techniques using blood collection tubes do not require special equipment and are inexpensive; however, removal of PRP manually is prone to greater operator error and greater potential for bacterial contamination because of the open nature of the final PRP harvest. Development of an inexpensive point-of-care alternative to commercial systems capable of producing a product free of bacterial contamination would make PRP therapy more widely available to horse owners of all economic means.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the quality and bacteriologic safety of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) produced by 3 simple, inexpensive tube centrifugation methods and compare the results to those produced by a commercial system. We hypothesized that one of the 3 tube methods would concentrate platelets within a clinically useful range with acceptable WBC concentration.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

This project was approved by and performed according to the guidelines of the Virginia Tech Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Informed consent was obtained from the owner for each horse in the study. Twenty-six healthy horses without clinical signs of disease were used for the study [7 mares, 19 geldings; 2 to 12 years old (mean: 6.4 ± 2.2 y)]. Breeds included Quarter horse (n = 2), American Paint horse (n = 4), Tennessee Walking horse (n = 5), Thoroughbred (n = 5), Standardbred (n = 1), and mixed breed (n = 9). Horses used for the study were owned by clients and staff of the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine (VMRCVM).

Blood collection and laboratory set-up

Blood was collected from either the left or right jugular vein. The venipuncture site was prepared using standard aseptic technique. Sterile technique was maintained throughout the collection process. Blood (180 mL) was collected into three 60-mL syringes each containing 8 mL of acid citrate dextrose-A anticoagulant, using an 18-gauge, 1.5-inch hypodermic needle and a sterile extension set. Syringes were gently rocked during collection and transport to the lab to ensure proper mixing. Platelet-rich plasma was processed using 4 techniques: 2 blood tube centrifugation methods, a conical tube method, and a commercial method (GenesisCS; Vet-Stem, Poway, California, USA). Samples were processed using sterile technique on a laboratory bench top cleaned with 70% ethanol. Prior to harvest of PRP using the various techniques described, the cap of the blood collection tube was disinfected with alcohol, allowed to dry, and removed. Centrifuges were calibrated prior to starting the study. Before aliquotting blood for processing, a 3-mL sample of whole blood was saved for complete blood (cell) count (CBC) and culture.

Blood tube centrifugation methods for processing PRP

The protocols utilized for the blood tube centrifugation method were selected based on the equine literature and preliminary studies. For each of the blood tube centrifugation methods, 3 glass blood tubes (red top, BD Vacutainer Serum Tubes; Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) were each filled with 10 mL of blood. The amount of blood in each tube was standardized by weight. The tubes were centrifuged in a table top centrifuge for 3 min at either 1200 × g (red top 1200g) or 2000 × g (red top 2000g). The platelet poor plasma (PPP) was removed from the top of the tube using a sterile 14-gauge pipetting needle (blunt end pipetting needle; Poppers and Sons, New Hyde Park, New York, USA), and a 6-mL syringe, leaving a standardized 1-mL volume of PRP. The remaining plasma, buffy coat, and top 1 mm of the packed RBCs was collected for a total of 1 mL of PRP from each tube. Platelet-rich plasma samples from the 3 tubes were pooled, yielding a total of 3 mL of PRP for each tube centrifugation method.

Conical tube method for processing PRP

A 30-mL aliquot of blood was placed into a sterile, skirted, polypropylene, 50-mL conical centrifuge tube (Corning Life Sciences, Lowell, Massachusetts, USA). The tubes were centrifuged for 15 min at 720 × g (conical 720g). The PPP was removed using a sterile 14-gauge pipetting needle (as described) and a 20-mL syringe, leaving a standardized 3 mL volume of PRP. The remaining plasma, buffy coat, and top 1 mm of the packed RBCs were collected for a total of 3 mL of PRP.

Commercial method for processing PRP

The sterile disposable (GenesisCS) was filled with 30 mL of blood and centrifuged for 15 min at 720 × g (Genesis 720g) in a specialized centrifuge (Hermle Z300; Labnet, Woodridge, New Jersey, USA) designed to accommodate the disposable and according to manufacturer’s instructions. A 3-way stopcock with attached 20-mL and 6-mL syringes was connected to the access port on the disposable. A line drawn 3 mm above the packed RBCs was used to standardize the amount of PPP removed. The 20-mL syringe was used to aspirate the PPP until the aspiration disc reached the line drawn on the tube, the stopcock was turned, and the remaining plasma, buffy coat, and top 1 mm of the packed RBCs were collected for a total of 3 mL of PRP.

Sample analysis

Whole blood and PRP samples for all horses were submitted to the VMRCVM Clinical Pathology Laboratory for automated quantification of platelet, WBC and RBC counts, and MPV (Advia 2120 Hematology Analyzer; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Tarrytown, New York, USA). All samples were placed on a rocker for 10 min prior to analysis to ensure adequate mixing.

Bacteriologic culture of PRP samples

Samples of whole blood and PRP from each horse were reserved for aerobic and anaerobic culture. A 250-μL aliquot of each sample was transferred to a 5% sheep blood agar plate and a pre-reduced anaerobic plate (Anaerobe Systems, Morgan Hill, California, USA). All plates were incubated at 37°C; blood agar plates were maintained in an atmosphere of 7% CO2. Cultures were checked daily for growth and reported as negative if there was no visible growth by day 7. Positive cultures were submitted to the VMRCVM Microbiology Laboratory for identification.

Statistical analysis

Data for platelets and WBCs were analyzed by 2 statistical methods. Normal probability plots were generated to verify that MPV and fold change for RBC, WBC, and platelets, and the ratio of fold changes for WBC and platelets (WBC:Platelet) followed an approximately normal distribution. The effect of method on these outcomes (MPV and fold change for RBC, WBC, and platelets, and WBC:Platelet) was then assessed using mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s procedure for multiple comparisons (Proc MIXED; SAS version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). The linear model specified method as a fixed effect, horse as a random effect and Kenward-Roger denominator degrees of freedom. For each model, residual plots were inspected to verify model adequacy (i.e., that the errors followed a normal distribution with constant variance).

Estimates of what might be considered clinically useful products were extrapolated from the literature (6,8,27–31,33,37). Most products produced by point-of-care devices used commonly in equine and human practice are leukocyte rich and were therefore deemed a relevant comparison for this study (6,38–41). Absolute numbers of platelets and WBC were categorized as either clinically “acceptable” or “unacceptable” using cutoff points for clinically acceptable platelet and WBC values as > 250 000 platelets/μL and < 30 000 WBC/μL, respectively. Subsequently, the number of “acceptable” samples (separately for platelets or WBCs) was compared between the methods using binary logistic generalized estimating equations (GEE) (Proc GENMOD, SAS version 9.2). The model specified sample classification (“acceptable” versus “unacceptable”) as outcome, method as a predictor, logit as the link function, binomial as the distribution, and horse as a blocking factor (with an independent working correlation matrix). P-values were based on type 3 Wald statistics. Statistical significance for all analyses was set at P < 0.05.

Results

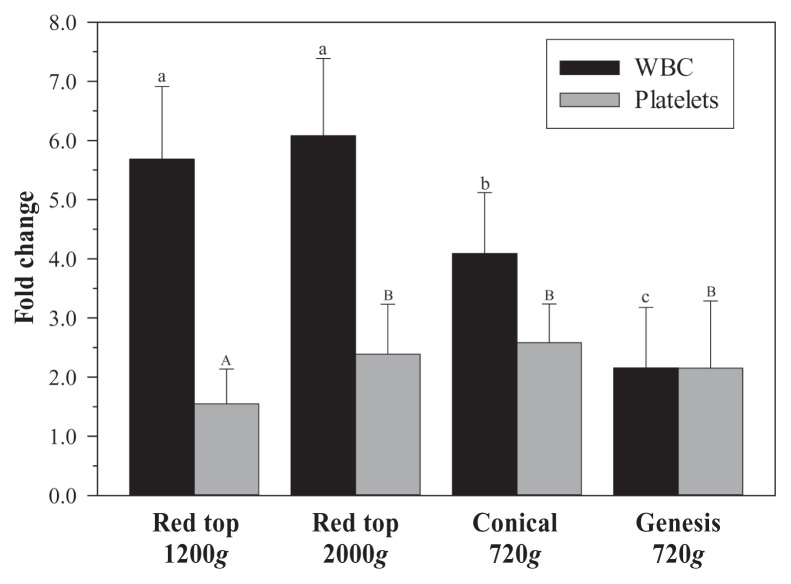

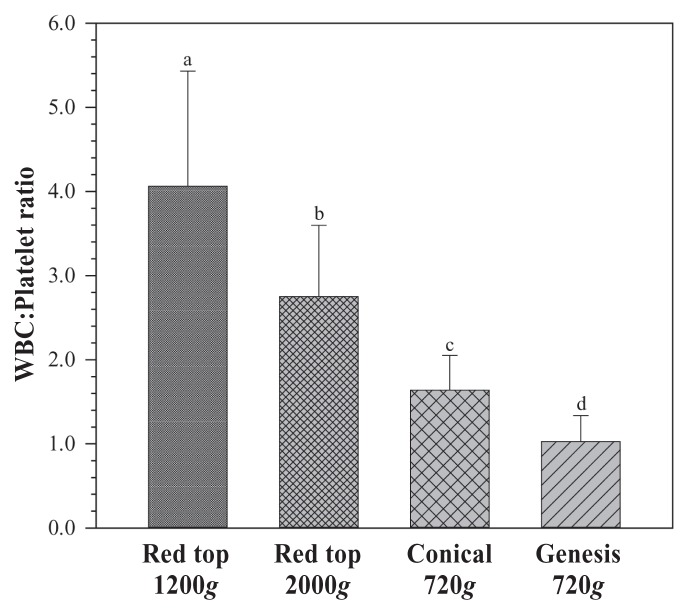

Mean platelet fold change was greatest for the conical method (2.58×); however, this difference only reached statistical significance in comparison to 1200g (P < 0.0001; Figure 1). Mean WBC fold change for the Genesis method was significantly lower than for the other 3 methods (P < 0.0001; Figure 1). Mean WBC fold change for the conical method was significantly lower than the means of either red top 1200g or 2000g. Mean WBC:Platelet ratios were significantly different between each of the groups (P < 0.0001; Figure 2); red top 1200g and 2000g were significantly greater than either conical or Genesis method and the conical method was significantly greater than Genesis.

Figure 1.

Fold change of white blood cells (WBCs) and platelets for 4 methods of preparing platelet rich plasma (PRP). Mean ± standard deviation (SD). Superscript letters indicate significant differences between groups.

Figure 2.

White blood cell:platelet ratio for 4 methods of preparing platelet rich plasma (PRP). Mean ± standard deviation (SD). Superscript letters indicate significant differences between groups.

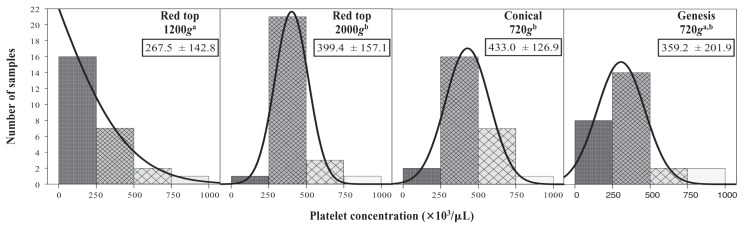

Mean total platelet counts were significantly different between groups (P < 0.0001; Figure 3). Platelet counts for red top 1200g were significantly less than for red top 2000g and conical 720g. Because the mean platelet count for a group may not accurately represent the number of samples containing platelets at clinically relevant concentrations (> 250 000/μL), the frequency of samples considered “acceptable” versus “unacceptable” was analyzed and compared in pairwise fashion to determine an odds ratio (OR) (Table 1). Odds ratios for all pairwise comparisons are reported; however, only that comparing the conical and Genesis methods is considered clinically relevant because of the unacceptably high WBC numbers in the 2 red top tube methods. The conical method resulted in a significantly greater number of “acceptable” samples (92.3%) compared with the Genesis method (69.2%) when considering platelet number alone (OR = 3.67, P = 0.04).

Figure 3.

Total number of samples for each of 4 methods of preparing platelet rich plasma (PRP) achieving relevant ranges for platelet concentration and associated Gaussian curves demonstrating distribution of samples. Superscript letters indicate significant differences between groups. Small boxes: Mean platelet count ± standard deviation (SD) (× 103/μL).

Table 1.

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals for platelet and white blood cell (WBC) numbers based on pairwise comparisons between groups. An OR greater than 1.00 indicates that the first member of the pair has a greater number of “acceptable” samples. An OR less than 1.00 indicates that the second member of the pair has a greater number of “acceptable” samples

| Platelet numbers | WBC numbers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Pairwise comparison | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

| Red top 1200g versus Genesis 720g | 0.27 (0.08–0.93) | 0.04 | 0.003 (0.001–0.014) | < 0.001 |

| Red top 2000g versus Genesis 720g | 2.44 (0.89–6.69) | 0.08 | 0.003 (0.001–0.011) | < 0.001 |

| Conical 720g versus Genesis 720g | 3.67 (1.07–12.63) | 0.04 | 0.049 (0.013–0.189) | < 0.001 |

| Red top 2000g versus Red top 1200g | 8.88 (3.49–22.60) | < 0.001 | 0.85 (0.50–1.47) | 0.57 |

| Conical 720g versus Red top 1200g | 13.37 (4.42–40.43) | < 0.001 | 15.13 (3.41–67.01) | 0.001 |

| Conical 720g versus Red top 2000g | 1.50 (0.60–3.78) | 0.38 | 17.70 (3.83–81.75) | 0.001 |

White blood cell counts for red top 1200g and 2000g were significantly greater than for either conical or Genesis method and WBC counts for the conical method were significantly greater than for Genesis. The Genesis system had more samples with WBC within the “acceptable” range (96.1%) than the other methods and the conical method had significantly more WBC within the “acceptable” range (69.2%) than red top 1200g or 2000g (26.9% each) based on the GEE analysis (P < 0.0001; Table 1).

Mean MPV for the red top tube methods was not significantly different from whole blood, and mean MPV for the conical and Genesis methods were significantly lower than for whole blood (Table 2; P = 0.0001). Mean RBC fold change for Genesis was significantly lower than for the other groups (Table 2; P < 0.0001). There was no bacterial growth on any plates up to day 6. A single small colony was present on 6/280 samples (2.1%) on day 7: whole blood, red top 1200g, and Genesis (2 each). Isolated organisms included Kocuria rosea (n = 3), Micrococcus species (n = 2), and Propionibacterium sp (n = 1).

Table 2.

Mean platelet volume (MPV) and red blood cell (RBC) fold change for whole blood and 4 methods of preparing platelet rich plasma (PRP). Mean ± standard deviation (SD). Superscript letters indicate significant differences between groups

| Preparation method | MPV (fL) | RBC fold change |

|---|---|---|

| Whole blood | 9.63 ± 1.29a | N/A |

| Red top 1200g | 9.20 ± 1.05a,b | 0.79 ± 0.23a |

| Red top 2000g | 9.11 ± 1.29a,b | 0.84 ± 0.19a |

| Conical 720g | 8.33 ± 1.38c | 1.06 ± 0.31b |

| Genesis 720g | 8.56 ± 0.98b,c | 0.63 ± 0.27c |

NA — not applicable

Discussion

The goal of the study was to identify a simple, inexpensive means of producing bacteria-free PRP for clinical applications in the horse that would make this regenerative medicine therapy more widely available. We chose only protocols involving a single centrifugation rather than double centrifugation to minimize the potential for bacterial contamination and to keep the processing as simple as possible for application in clinical practice. The 2 methods utilizing blood collection tubes were capable of marginal platelet concentration but were deemed clinically unacceptable due to excessive concentration of WBCs. The conical tube method had adequate ability to concentrate platelets without undue WBC concentration and may be a suitable alternative to commercial systems for selected equine applications.

Equine-specific parameters for platelet and WBC counts for clinical applications of PRP are lacking. Although fold change is commonly used to evaluate the quality of platelet concentrates, absolute numbers of platelets may provide a more accurate standard of quality. Statistical analyses performed in this study yielded comparable results for both fold change and raw platelet numbers as a means of comparison. Target values for platelet concentrations in PRP described in the equine literature are extrapolated from the human literature and do not take into account potentially important species differences in platelet counts or physiology such as mechanism of degranulation or growth factor contents per platelet (33,34). Neither human nor equine values suggested in the literature have a basis in controlled scientific studies and are instead inferred from in vitro studies (28,30), suggesting that further work be done to identify optimal doses of platelets for specific applications. Studies involving in vivo use of PRP in horses are limited and reported platelet numbers are highly variable (5–7,13). Additional equine-specific research is needed to define the minimum platelet concentration necessary to achieve beneficial biologic effects.

Recent studies in pigs and humans suggest that lower platelet concentrations may be equally or more effective than higher concentrations and that high platelet concentrations may even have detrimental effects (31,32). There was no significant difference in the mechanical properties in a porcine model of anterior cruciate ligament repair between 3× and 5× platelet concentration (32). Human osteoblasts and fibroblasts had maximal cell proliferation at 2.5× platelet concentration compared to 3.5× and 4.2 to 5.5× (31). The mean platelet concentration achieved using the conical method was within the range of those described in these studies and another equine study (4).

The importance of low WBC numbers in autologous platelet concentrates is controversial; the use of leukocyte reduced PRP (< 3000 WBC/μL) has been suggested for use in specific applications (16–18,21,37). White blood cells were positively correlated with expression of catabolic cytokines and negatively correlated with matrix gene expression in human PRP products (19) and in equine tendon and ligament explants treated with PRP (21). Although this in vitro work is compelling, the clinical relevance is unknown because of the lack of direct clinical comparison between leukocyte rich and leukocyte depleted products in vivo (18).

White blood cells do play a beneficial role in enhancing tissue repair as a result of their immunomodulatory and antimicrobial effects. Myeloperoxidase contained within neutrophils and monocytes contributes to the antimicrobial activity of PRP (42–45). Leukocyte rich PRP reduced wound drainage when applied following coronary artery bypass surgery (40) and has shown beneficial effects in human and equine studies, including application during open subacromial decompression (39), chronic elbow tendinosis (41), and delayed bone union (38) in human patients and mechanically induced tendon lesions in horses (6). Human patients reported diminished pain and inflammation at the treated sites (39,41). In addition, leukocytes release VEGF and PDGF themselves and stimulate platelets to release growth factors, enhancing the growth factor concentration over leukocyte-reduced PRP (17,20,46).

Mean platelet volume (MPV) is a measure of average platelet size in a sample and increases as platelets become activated and change from a discoid to spherical shape (47). Platelet activation may be undesirable for applications where slow release of growth factors from gradual platelet degranulation is considered beneficial. A PRP sample with an MPV similar to whole blood implies that processing did not cause platelet activation. Mean platelet volume in our PRP samples was not significantly higher than that from whole blood for any of the processing methods, suggesting lack of platelet activation.

Despite using clean, but not strictly aseptic techniques (i.e., processing the samples in a laminar flow hood), only 2.1% of samples had bacterial growth. The bacterial species that were cultured were most likely environmental contaminants associated with the culture process itself. The ability to process PRP samples without contamination is critical due to the inability to filter-sterilize the end product prior to injection. Use of a laminar flow hood for processing may be ideal; however, in most practice situations this may not be a realistic option. Based on our results, the methods described in this study appear to be adequate, when strictly adhered to, to produce a clinically safe product free from bacterial contamination. These results are consistent with previous reports (48).

The repeatability of a technique should be considered when selecting a method for clinical applications. Evaluation of platelet and WBC counts in whole blood and platelet concentrates should be performed on each sample to more accurately detail the quality of the product used, regardless of the method of concentration. The conical tube method described in this study achieved the highest number of samples with platelet numbers exceeding 250 000/μL and platelet fold change greater than 2.5. Recent studies suggest that these values, although lower than what some authors propose as the therapeutic range, may be clinically relevant (31,32). The WBC numbers achieved using this method may also be within a clinically acceptable range based on available information (6,38). The supplies needed for the conical tube method cost less than $20 US dollars per sample and are readily available, including the centrifuge. Based on the results of this study, the conical tube method of PRP processing is bacteriologically safe when performed under controlled aseptic conditions and may be a suitable clinical alternative to commercial systems in low budget cases.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Vet-Stem, Inc. for their generous donation of GenesisCS kits. CVJ

Footnotes

Presented at the American College of Veterinary Surgeons Veterinary Symposium, Chicago, Illinois, November 2011.

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

Funded by the Virginia Horse Industry Board and the American College of Veterinary Surgeons Foundation Surgeon-in-Training Grant.

References

- 1.Sampson S, Gerhardt M, Mandelbaum B. Platelet rich plasma injection grafts for musculoskeletal injuries: A review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1:165–174. doi: 10.1007/s12178-008-9032-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simman R, Hoffmann A, Bohinc RJ, Peterson WC, Russ AJ. Role of platelet-rich plasma in acceleration of bone fracture healing. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61:337–344. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318157a185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikolidakis D, Jansen JA. The biology of platelet-rich plasma and its application in oral surgery: Literature review. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14:249–258. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schnabel LV, Mohammed HO, Miller BJ, et al. Platelet rich plasma (PRP) enhances anabolic gene expression patterns in flexor digitorum superficialis tendons. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:230–240. doi: 10.1002/jor.20278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waselau M, Sutter WW, Genovese RL, Bertone AL. Intralesional injection of platelet-rich plasma followed by controlled exercise for treatment of midbody suspensory ligament desmitis in Standardbred racehorses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;232:1515–1520. doi: 10.2460/javma.232.10.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosch G, van Schie HT, de Groot MW, et al. Effects of platelet-rich plasma on the quality of repair of mechanically induced core lesions in equine superficial digital flexor tendons: A placebo-controlled experimental study. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:211–217. doi: 10.1002/jor.20980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeRossi R, Coelho AC, Mello GS, et al. Effects of platelet-rich plasma gel on skin healing in surgical wound in horses. Acta Cir Bras. 2009;24:276–281. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502009000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anitua E, Andia I, Ardanza B, Nurden P, Nurden AT. Autologous platelets as a source of proteins for healing and tissue regeneration. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:4–15. doi: 10.1160/TH03-07-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: Evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutter WW, Kaneps AJ, Bertone AL. Comparison of hematologic values and transforming growth factor-beta and insulin-like growth factor concentrations in platelet concentrates obtained by use of buffy coat and apheresis methods from equine blood. Am J Vet Res. 2004;65:924–930. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2004.65.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eppley BL, Woodell JE, Higgins J. Platelet quantification and growth factor analysis from platelet-rich plasma: Implications for wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1502–1508. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000138251.07040.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter CA, Jolly DG, Worden CE, Sr, Hendren DG, Kane CJ. Platelet-rich plasma gel promotes differentiation and regeneration during equine wound healing. Exp Mol Pathol. 2003;74:244–255. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4800(03)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monteiro SO, Lepage OM, Theoret CL. Effects of platelet-rich plasma on the repair of wounds on the distal aspect of the forelimb in horses. Am J Vet Res. 2009;70:277–282. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.70.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Bue M, Ricco S, Conti V, Merli E, Ramoni R, Grolli S. Platelet lysate promotes in vitro proliferation of equine mesenchymal stem cells and tenocytes. Vet Res Commun. 2007;31(Suppl 1):289–292. doi: 10.1007/s11259-007-0099-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Bue M, Ricco S, Ramoni R, Conti V, Gnudi G, Grolli S. Equine adipose-tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells and platelet concentrates: Their association in vitro and in vivo. Vet Res Commun. 2008;32(Suppl 1):S51–55. doi: 10.1007/s11259-008-9093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnabel LV, Fortier LA, McCarrel TM, Sundman EA, Boswell S. PRP: What we know and where are we going? Proc Am Col Vet Surg Vet Symp. 2011;21:103. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castillo TN, Pouliot MA, Kim HJ, Dragoo JL. Comparison of growth factor and platelet concentration from commercial platelet-rich plasma separation systems. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:266–271. doi: 10.1177/0363546510387517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLellan J, Plevin S. Does it matter which platelet-rich plasma we use? Equine Vet Educ. 2011;23:101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sundman EA, Cole BJ, Fortier LA. Growth factor and catabolic cytokine concentrations are influenced by the cellular composition of platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:2135–2140. doi: 10.1177/0363546511417792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werther K, Christensen IJ, Nielsen HJ. Determination of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in circulating blood: Significance of VEGF in various leucocytes and platelets. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2002;62:343–350. doi: 10.1080/00365510260296492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarrel T, Fortier L. Temporal growth factor release from platelet-rich plasma, trehalose lyophilized platelets, and bone marrow aspirate and their effect on tendon and ligament gene expression. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1033–1042. doi: 10.1002/jor.20853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: From pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bordin JO, Heddle NM, Blajchman MA. Biologic effects of leukocytes present in transfused cellular blood products. Blood. 1994;84:1703–1721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davenport RD, Kunkel SL. Cytokine roles in hemolytic and nonhemolytic transfusion reactions. Transfus Med Rev. 1994;8:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(94)70108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muylle L, Peetermans ME. Effect of prestorage leukocyte removal on the cytokine levels in stored platelet concentrates. Vox Sang. 1994;66:14–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1994.tb00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer DS, Aye MT, Dumont L, et al. Prevention of cytokine accumulation in platelets obtained with the COBE spectra apheresis system. Vox Sang. 1998;75:115–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marx RE, Carlson ER, Eichstaedt RM, Schimmele SR, Strauss JE, Georgeff KR. Platelet-rich plasma: Growth factor enhancement for bone grafts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:638–646. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Kalen A, Risto O, Wahlstrom O. Fibroblast proliferation due to exposure to a platelet concentrate in vitro is pH dependent. Wound Repair Regen. 2002;10:336–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2002.10510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weibrich G, Hansen T, Kleis W, Buch R, Hitzler WE. Effect of platelet concentration in platelet-rich plasma on peri-implant bone regeneration. Bone. 2004;34:665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haynesworth SE, Kadiyala S, Liang L, Bruder SP. Mitogenic stimulation of human mesenchymal stem cells by platelet releasate suggests a mechanism for enhancement of bone repair by platelet concentrate. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 1996;21:462. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graziani F, Cei S, Ducci F, Giuca MR, Donos N, Gabriele M. In vitro effects of different concentration of PRP on primary bone and gingival cell lines. Preliminary results. Minerva Stomatol. 2005;54:15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mastrangelo AN, Vavken P, Fleming BC, Harrison SL, Murray MM. Reduced platelet concentration does not harm PRP effectiveness for ACL repair in a porcine in vivo model. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1002–1007. doi: 10.1002/jor.21375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boudreaux M, Ebbe S. Comparison of platelet number, mean platelet volume and platelet mass in five mammalian species. Comp Haematol Int. 1998;8:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gader AG, Ghumlas AK, Hussain MF, Haidari AA, White JG. The ultrastructure of camel blood platelets: A comparative study with human, bovine, and equine cells. Platelets. 2008;19:51–58. doi: 10.1080/09537100701627151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arguelles D, Carmona JU, Pastor J, et al. Evaluation of single and double centrifugation tube methods for concentrating equine platelets. Res Vet Sci. 2006;81:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christensen K, Vang S, Brady C, et al. Autologous platelet gel: An in vitro analysis of platelet-rich plasma using multiple cycles. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2006;38:249–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCarrel T, Minas T, Fortier L. Optimization of white blood cell concentration in platelet rich plasma (PRP) for the treatment of tendonitis. Vet Surgery. 2011;40:E37. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bielecki T, Gazdzik TS, Szczepanski T. Benefit of percutaneous injection of autologous platelet-leukocyte-rich gel in patients with delayed union and nonunion. Eur Surg Res. 2008;40:289–296. doi: 10.1159/000114967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Everts PA, Devilee RJ, Brown Mahoney C, et al. Exogenous application of platelet-leukocyte gel during open subacromial decompression contributes to improved patient outcome. A prospective randomized double-blind study. Eur Surg Res. 2008;40:203–210. doi: 10.1159/000110862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khalafi RS, Bradford DW, Wilson MG. Topical application of autologous blood products during surgical closure following a coronary artery bypass graft. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:360–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mishra A, Pavelko T. Treatment of chronic elbow tendinosis with buffered platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1774–1778. doi: 10.1177/0363546506288850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bielecki TM, Gazdzik TS, Arendt J, Szczepanski T, Krol W, Wielkoszynski T. Antibacterial effect of autologous platelet gel enriched with growth factors and other active substances: An in vitro study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:417–420. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B3.18491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moojen DJ, Everts PA, Schure RM, et al. Antimicrobial activity of platelet-leukocyte gel against Staphylococcus aureus. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:404–410. doi: 10.1002/jor.20519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cieslik-Bielecka A, Gazdzik TS, Bielecki TM, Cieslik T. Why the platelet-rich gel has antimicrobial activity? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:303–305. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lincoln JA, Lefkowitz DL, Cain T, et al. Exogenous myeloperoxidase enhances bacterial phagocytosis and intracellular killing by macrophages. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3042–3047. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3042-3047.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zimmermann R, Jakubietz R, Jakubietz M, et al. Different preparation methods to obtain platelet components as a source of growth factors for local application. Transfusion. 2001;41:1217–1224. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41101217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laufer N, Grover NB, Ben-Sasson S, Freund H. Effects of adenosine diphosphate, colchicine and temperature on size of human platelets. Thromb Haemost. 1979;41:491–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alvarez ME, Giraldo CE, Carmona JU. Monitoring bacterial contamination in equine platelet concentrates obtained by the tube method in a clean laboratory environment under three different technical conditions. Equine Vet J. 2010;42:63–67. doi: 10.2746/042516409X455221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]