Abstract

Lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) are a large group of more than 50 different inherited metabolic diseases which, in the great majority of cases, result from the defective function of specific lysosomal enzymes and, in cases, of non-enzymatic lysosomal proteins or non-lysosomal proteins involved in lysosomal biogenesis. The progressive lysosomal accumulation of undegraded metabolites results in generalised cell and tissue dysfunction, and, therefore, multi-systemic pathology. Storage may begin during early embryonic development, and the clinical presentation for LSDs can vary from an early and severe phenotype to late-onset mild disease. The diagnosis of most LSDs--after accurate clinical/paraclinical evaluation, including the analysis of some urinary metabolites--is based mainly on the detection of a specific enzymatic deficiency. In these cases, molecular genetic testing (MGT) can refine the enzymatic diagnosis. Once the genotype of an individual LSD patient has been ascertained, genetic counselling should include prediction of the possible phenotype and the identification of carriers in the family at risk. MGT is essential for the identification of genetic disorders resulting from non-enzymatic lysosomal protein defects and is complementary to biochemical genetic testing (BGT) in complex situations, such as in cases of enzymatic pseudodeficiencies. Prenatal diagnosis is performed on the most appropriate samples, which include fresh or cultured chorionic villus sampling or cultured amniotic fluid. The choice of the test--enzymatic and/or molecular--is based on the characteristics of the defect to be investigated. For prenatal MGT, the genotype of the family index case must be known. The availability of both tests, enzymatic and molecular, enormously increases the reliability of the entire prenatal diagnostic procedure. To conclude, BGT and MGT are mostly complementary for post- and prenatal diagnosis of LSDs. Whenever genotype/phenotype correlations are available, they can be helpful in predicting prognosis and in making decisions about therapy.

Introduction

Although the first clinical descriptions of patients with lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) were reported at the end of the nineteenth century by Warren Tay (1881)[1] and Bernard Sachs (1887; Tay-Sachs disease),[2] and by Phillipe Gaucher (1882) (Gaucher disease),[3] the biochemical nature of the accumulated products was only elucidated some 50 years later (1934) in the latter, as glucocerebroside [4]. Considerably more time was then required for the demonstration by Hers (1963) that there was a link between an enzyme deficiency and a storage disorder (Pompe disease) [5]. In the following years, the elucidation of several enzyme defects led to the initial classification of the various types of LSDs according to their clinical pictures, pathological manifestations and the biochemical nature of the undegraded substrates. Although part of this classification is still maintained, it is continually updated on the basis of newly acquired knowledge on the underlying molecular pathology.

At present, more than 50 LSDs are known. The majority of these result from a deficiency of specific lysosomal enzymes. In a few cases, non-enzymatic lysosomal proteins or non-lysosomal proteins involved in lysosomal biogenesis are deficient.

The common biochemical hallmark of these diseases is the accumulation of undigested metabolites in the lysosome. This can arise through several mechanisms as a result of defects in any aspect of lysosomal biology that hampers the catabolism of molecules in the lysosome, or the egress of naturally occurring molecules from the lysosome. Lysosomal accumulation activates a variety of pathogenetic cascades that result in complex clinical pictures characterised by multi-systemic involvement [6-10]. Phenotypic expression is extremely variable, as it depends on the specific macromolecule accumulated, the site of production and degradation of the specific metabolites, the residual enzymatic expression and the general genetic background of the patient. Many LSDs have phenotypes that have been recognised as infantile, juvenile and adult [7].

Table 1 summarises the various defective proteins, the type(s) of main accumulated metabolites and the distinct genes responsible for each specific LSD type/subtype. It also reports screening and diagnostic tests available for each disease.

Table 1.

Lysosomal storage disorders

| OMIM | Disease | Defective protein | Main storage materials |

Preliminary test |

Gene symbol |

MIM ID |

Diagnostic test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPSs) | |||||||

| 607014 607015 607016 |

MPS I (Hurler, Scheie, Hurler/Scheie) |

α-Iduronidase | Dermatan sulphate, heparan sulphate |

GAGs (U) | IDUA | 252800 | BGT, MGT |

| 309900 | MPS II (Hunter) | Iduronate sulphatase | Dermatan sulphate, heparan sulphate |

GAGs (U) | IDS | 309900 | BGT, MGT |

| 252900 | MPS III A (Sanfilippo A) | Heparan sulphamidase | Heparan sulphate | GAGs (U) | SGSH | 605270 | BGT, MGT |

| 252920 | MPS III B (Sanfilippo B) | Acetyl α-glucosaminidase | Heparan sulphate | GAGs (U) | NAGLU | 609701 | BGT, MGT |

| 252930 | MPS III C (Sanfilippo C) | Acetyl CoA: α-glucosaminide N-acetyltransferase |

Heparan sulphate | GAGs (U) | HGSNAT | 610453 | BGT, MGT |

| 252940 | MPS III D (Sanfilippo D) | N-acetyl glucosamine-6-sulphatase |

Heparan sulphate | GAGs (U) | GNS | 607664 | BGT, MGT |

| 253000 | MPS IVA (Morquio A) | Acetyl galactosamine-6-sulphatase |

Keratan sulphate, chondroiotin 6-sulphate |

GAGs (U) | GALNS | 612222 | BGT, MGT |

| 253010 | MPS IV B (Morquio B) | β-Galactosidase | Keratan sulphate | GAGs (U) | GLB1 | 611458 | BGT, MGT |

| 253200 | MPS VI (Maroteaux-Lamy) |

Acetyl galactosamine 4-sulphatase (arylsulphatase B) |

Dermatan sulphate | GAGs (U) | ARSB | 611542 | BGT, MGT |

| 253220 | MPS VII (Sly) | β-Glucuronidase | Dermatan sulphate, heparan sulphate, chondroiotin 6-sulphate |

GAGs (U) | GUSB | 611499 | BGT, MGT |

| 601492 | MPS IX (Natowicz) | Hyaluronidase | Hyluronan | - | HYAL1 | 607071 | BGT, MGT |

| Sphingolipidoses | |||||||

| 301500 | Fabry | α-Galactosidase A | Globotriasylceramide | - | GLA | 300644 | BGT, MGT |

| 228000 | Farber | Acid ceramidase | Ceramide | - | ASAH1 | 613468 | BGT, MGT |

| 230500 230600 230650 |

Gangliosidosis GM1 (Types I, II, III) |

GM1-β-galactosidase | GM1 ganglioside, Keratan sulphate, oligos, glycolipids |

Oligos (U) | GLB1 | 611458 | BGT, MGT |

| 272800 | Gangliosidosis GM2, Tay-Sachs |

β-Hexosaminidase A | GM2 ganglioside, oligos, glycolipids |

- | HEXA | 606869 | BGT, MGT |

| 268800 | Gangliosidosis GM2, Sandhoff |

β-Hexosaminidase A + B | GM2 ganglioside, oligos |

- | HEXAB | 606873 | BGT, MGT |

| 230800 230900 231000 |

Gaucher (Types I, II, III) |

Glucosylceramidase | Glucosylceramide | Chito+(S) | GBA | 606463 | BGT, MGT |

| 245200 | Krabbe | β-Galactosylceramidase | Galactosylceramide | - | GALC | 606890 | BGT, MGT |

| 250100 | Metachromatic leucodystrophy |

Arylsulphatase A | Sulphatides | Sulphatides (U) |

ARSA | 607574 | BGT, MGT |

| 257200 607616 | Niemann-Pick (type A, type B) |

Sphingomyelinase | Sphingomyelin | - | SMPD1 | 607608 | BGT, MGT |

| Olygosaccharidoses (glycoproteinoses) | |||||||

| 208400 | Aspartylglicosaminuria | Glycosylasparaginase | Aspartylglucosamine | Oligos (U) | AGA | 613228 | BGT, MGT |

| 230000 | Fucosidosis | α-Fucosidase | Glycoproteins, glycolipids, Fucoside-rich oligos |

Oligos (U) | FUCA1 | 612280 | BGT, MGT |

| 248500 | α-Mannosidosis | α-Mannosidase | Mannose-rich oligos | Oligos (U) | MAN2B1 | 609458 | BGT, MGT |

| 248510 | β-Mannosidosis | β-Mannosidase | Man(β1 → 4)GlnNAc | Oligos (U) | MANBA | 609489 | BGT, MGT |

| 609241 | Schindler | N-acetylgalactosaminidase | Sialylated/ asialoglycopeptides, glycolipids |

Oligos (U) | NAGA | 104170 | BGT, MGT |

| 256550 | Sialidosis | Neuraminidase | Oligos, glycopeptides | Bound SA (U), Oligos (U) |

NEU1 | 608272 | BGT, MGT |

| Glycogenoses | |||||||

| 232300 | Glycogenosis II/Pompe | α1,4-glucosidase (acid maltase) | Glycogen | CK (S) | GAA | 606800 | BGT, MGT |

| Lipidoses | |||||||

| 278000 | Wolman/CESD | Acid lipase | Cholesterol esters | - | LIPA | 613497 | BGT, MGT |

| Non-enzymatic lysosomal protein defect | |||||||

| 272750 | Gangliosidosis GM2, activator defect |

GM2 activator protein | GM2 ganglioside, oligos |

- | GM2A | 613109 | MGT |

| 249900 | Metachromatic leucodystrophy |

Saposin B | Sulphatides | Sulphatides (U) |

PSAP | 176801 | MGT |

| 611722 | Krabbe | Saposin A | Galactosylceramide | - | PSAP | 176801 | MGT |

| 610539 | Gaucher | Saposin C | Glucosylceramide | - | PSAP | 176801 | MGT |

| Transmembrane protein defect | |||||||

| Transporters | |||||||

| 269920 604369 |

Sialic acid storage disease; infantile form (ISSD) and adult form (Salla) |

Sialin | Sialic acid | Free SA (U) | SLC17A5 | 604322 | MGT |

| 219800 | Cystinosis | Cystinosin | Cystine | - | CTNS | 606272 | MGT |

| 257220 | Niemann-Pick Type C1 | Niemann-Pick type 1 (NPC1) | Cholesterol and sphingolipids |

Chito+(S) | NPC1 | 607623 | Filipin test, MGT |

| 607625 | Niemann-Pick, Type C2 | Niemann-Pick type 2 (NPC2) | Cholesterol and sphingolipids |

Chito+(S) | NPC2 | 601015 | Filipin test, MGT |

| Structural Proteins | |||||||

| 300257 | Danon | Lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 |

Cytoplasmatic debris and glycogen |

- | LAMP2 | 309060 | MGT |

| 252650 | Mucolipidosis IV | Mucolipin | Lipids | - | MCOLN1 | 605248 | MGT |

| Lysosomal enzyme protection defect | |||||||

| 256540 | Galactosialidosis | Protective protein cathepsin A (PPCA) |

Sialyloligosaccharides | Bound SA (U), Oligos (U) |

CTSA | 613111 | BGTa, MGT |

| Post-translational processing defect | |||||||

| 272200 | Multiple sulphatase deficiency |

Multiple sulphatase | Sulphatides, glycolipids, GAGs |

Sulphatides (U), GAGs (U) |

SUMF1 | 607939 | BGTb, MGT |

| Trafficking defect in lysosomal enzymes | |||||||

| 252500 252600 |

Mucolipidosis IIα/β, IIIα/β |

GlcNAc-1-P transferase | Oligos, GAGs, lipids | Oligos (U) | GNPTAB | 607840 | BGTc, MGT |

| 232605 | Mucolipidosis IIIγ | GlcNAc-1-P transferase | Oligos, GAGs, lipids | Oligos (U) | GNPTG | 607838 | BGTc, MGT |

| Polypeptide degradation defect | |||||||

| 265800 | Pycnodysostosis | Cathepsin K | Bone proteins | X-ray | CTSK | 601105 | MGT |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCLs) | |||||||

| 256730 | NCL 1 | Palmitoyl protein thioesterase (PPT1) |

Saposins A and D | Ultrastructure | PPT1 | 600722 | BGT, MGT |

| 204500 | NCL 2 | Tripeptidyl peptidase 1 (TPP1) | Subunit c of ATP synthase |

Ultrastructure | TPP1 | 607998 | BGT, MGT |

| 204200 | NCL 3 | CLN3, lysosomal transmembrane protein |

Subunit c of ATP synthase |

Ultrastructure | CLN3 | 607042 | MGT |

| 256731 | NCL 5 | CLN5, soluble lysosomal protein |

Subunit c of ATP synthase |

Ultrastructure | CLN5 | 608102 | MGT |

| 601780 | NCL 6 | CLN6, transmembrane protein of ER |

Subunit c of ATP synthase |

Ultrastructure | CLN6 | 606725 | MGT |

| 610951 | NCL 7 | CLC7, lysosomal chloride channel |

Subunit c of ATP synthase |

Ultrastructure | MFSD8 | 611124 | MGT |

| 600143 | NCL 8 | CLN8, transmembrane protein of endoplasmic reticulum |

Subunit c of ATP synthase |

Ultrastructure | CLN8 | 607837 | MGT |

| 610127 | NCL 10 | Cathepsin D | Saposins A and D | Ultrastructure | CTSD | 116840 | MGT |

Abbreviations: CK, creatine kinase; CLN, with expansion; GAGs, glysosaminoglycans; GLcNAc-1-P, with expansion; Oligos, oligosaccharides; S, serum; SA, sialic acid; U, urine; Chito, chitotriosidase

aDefect of β-galactosidase and neuraminidase and/or cathepsin A

bDecrease in some lysosomal and non-lysosomal sulphatases

cSome lysosomal hydrolase activities increased in plasma and decreased in cultured fibroblasts

†Note that 5-7 per cent of the population have a recessively inherited defect in the chitotriosidase gene, which leads to false-negative values [11].

The endo-lysosomal system

The original concept that the lysosome is only one component of a series of unconnected intracellular organelles of the endo-lysosomal system[12] has been widely modified by recent studies. Lysosomal function is now considered in the larger context of the endosomal/lysosomal system [13]. In this highly dynamic system, which mediates the internalisation, recycling, transport and breakdown of cellular/extracellular components and facilitates dissociation of receptors from their ligands, the lysosome represents the greater degradative compartment of endocytic, phagocytic and autophagic pathways. Although hydrolytic enzymes are present in endosomes and lysosomes, they function optimally in the lysosome, as it is the most acidic compartment.

Lysosomal enzymes: Synthesis and trafficking

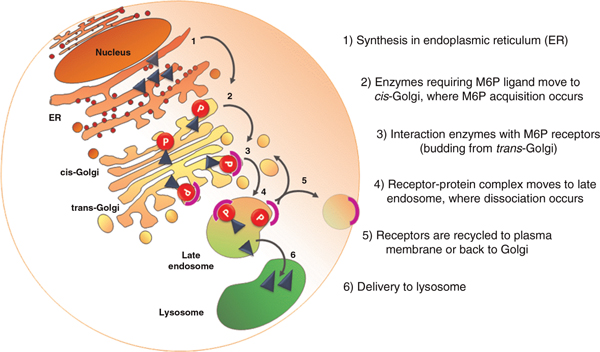

The lysosomal enzymes, which are synthesised in the rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER), move across the ER membrane to the lumen of the ER via an N-terminal signal sequence-dependent translocation. Once in the ER lumen, they are N-glycosylated and their signal sequence is cleaved. They then proceed to the Golgi compartment and, at this stage, the lysosomal enzymes, which require the mannose 6-phosphate (M6P) marker to enter the lysosome, acquire the M6P ligand by the sequential action of a phosphotransferase and a diesterase [14-16]. The receptor-protein complex then moves to the late endosome, where dissociation occurs; the hydrolase translocates into the lysosome and the receptor is recycled either to the Golgi apparatus or to the plasma membrane.

The final steps in the maturation of the lysosomal enzyme include proteolysis, folding and aggregation.

Not all lysosomal enzymes depend on the M6P pathway, however. Recently, it has been shown that the lysosomal integral membrane protein type 2 (LIMP-2)--a ubiquitously expressed transmembrane protein mainly found in the lysosomes and late endosomes--is a receptor for lysosomal M6P-independent targeting of glucocerebrosidase [17]. Figure 1 depicts a simplified scheme of M6P-dependent enzymes sorting to the lysosome.

Figure 1.

Simplified scheme of M6P-dependent enzymes sorting to the lysosome. The enzyme UDP-N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphotransferase, responsible for the initial step in the synthesis of the M6P recognition markers, plays a key role in lysosomal enzyme trafficking. Loss of this activity results in mucolipidoses II/III. Note that not all lysosomal enzymes depend on the M6P pathway.

Epidemiology

To date, worldwide epidemiological data on LSDs are not available or are limited to distinct populations. Apart from selected populations presenting a high prevalence for specific diseases, such as the Ashkenazi Jewish population at high risk for Gaucher disease,[18] Tay-Sachs disease and Niemann-Pick disease;[19] the Finnish population with its high incidence of aspartylglucosaminuria[20] and infantile/juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis,[21] as far as we know, prevalence data on LSDs, as a group, have only been reported in Greece,[22] the Netherlands,[23] Australia,[24] Portugal[25] and the Czech Republic [26]. As a group, overall incidence of LSDs is estimated at around 1:5,000-1:8,000 [24].

Classification: From the nature of the primary stored material to the type of molecular defect

LSDs can be grouped according to various classifications. While, in the past, they were classified on the basis of the nature of the accumulated substrate(s), more recently they have tended to be classified by the molecular defect (Table 1). A classic example of LSDs grouped by storage is the group of mucopolysaccharidoses, resulting from a deficiency of any one of 11 lysosomal enzymes that are involved in the sequential degradation of glycosaminoglycans (or mucopolysaccharides). In the group of sphingolipidoses, undegraded sphingolipids accumulate due to an enzyme deficiency or to an activator protein defect (the latter is classified in Table 1 as a group according to the molecular defect). Among the oligosaccharidoses (also known as glycoproteinoses), a single lysosomal hydrolase deficiency causes storage of oligosaccharides. In some cases, a deficiency in a single enzyme can result in the accumulation of different substrates. For example, GM1 gangliosidosis and Morquio-B disease are both caused by an acid β-galactosidase activity defect, yet results in GM1 ganglioside and keratan sulphate accumulation, respectively.

Table 1 also reports the emerging classification of diseases based on the recent understanding of the molecular basis LSDs. This subset includes groups of disorders due to: (i) non-enzymatic lysosomal protein defects; (ii) transmembrane protein defects (transporters and structural proteins); (iii) lysosomal enzyme protection defects; (iv) post-translational processing defects of lysosomal enzymes; (v) trafficking defects in lysosomal enzymes; and (vi) polypeptide degradation defects. Finally, another group includes the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCLs), which are considered to be lysosomal disorders, even though distinct characteristics exist. While, in the classic LSDs, the deficiency or dysfunction of an enzyme or transporter leads to lysosomal accumulation of specific undegraded substrates or metabolites, accumulating material in NCLs is not a disease-specific substrate but the subunit c of mitochondrial ATP synthase or sphingolipid activator proteins A and D [27].

Multiple sulphatase deficiency (MSD) is also worth mentioning. It has been shown that MSD results from a post-translational processing defect due to the failure of the Cα-formylglycine-generating enzyme to convert a specific cysteine residue, at the catalytic centre of all sulphatases, to a Cα-formylglycine residue [28,29]. Another rare LSD, galactosialidosis, is associated with the defective activity of two enzymes, β-galactosidase and sialidase. In these diseases--classified as 'lysosomal enzyme protection defects'--a multi-enzyme complex between the two lysosomal enzymes and the protective protein, cathepsin A (PPCA), forms improperly [30].

The breakdown of certain glycosphingolipids by their respective hydrolases requires the presence of activator proteins, known as sphingolipid activator proteins or saposins, encoded by two different genes. The defective function of the GM2 activator protein results in the AB variant of GM2 gangliosidosis [31]. The prosaposin is processed to four homologous saposins (Sap A, Sap B, Sap C and Sap D) [32]. Deficiency of Sap A, Sap B and Sap C results in variant forms of (i) Krabbe disease, involving abnormal storage of galactosylceramide;[33] (ii) meta-chromatic leucodystrophy (MLD), associated with sulphatide storage;[34] and (iii) Gaucher's disease, involving glucosylceramide storage,[35] respectively. Rarely, a total deficiency of prosaposin has been reported, resulting in a very severe phenotype [36].

Mucolipidoses result from defects in the enzymeUDP-N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphotransferase, which plays a key role in lysosomal enzyme trafficking [37]. This enzyme is responsible for the initial step in the synthesis of the M6P recognition markers essential for receptor-mediated transport of newly synthesised lysosomal enzymes to the endosomal/prelysosomal compartment (Figure 1). Failure to attach this recognition signal leads to the mistargeting of all lysosomal enzymes that require the M6P marker to enter the lysosome.

Laboratory diagnosis

Like other metabolic diseases, LSDs show remarkably varied clinical signs and symptoms, which may occur from the in utero period to late adulthood, depending on the complexity of the storage products and differences in their tissue distribution. Indeed, the recognition of LSD clinical features requires clinical expertise, as most of them are not specific and can be caused by defects in other metabolic pathways (mitochondrial and peroxisomal), or by environmental factors. Even in the presence of typical clinical signs and symptoms, samples and diagnostic tests are different for each group of lysosomal disorders and often are specific to a given disease.

The definitive diagnosis of LSDs therefore requires close collaboration between laboratory specialists and clinicians. For laboratory diagnosis, the clinician must select the appropriate test to be performed on the basis of a comprehensive evaluation that includes not only a physical assessment of the patient but also paraclinical test results (peripheral blood smears, radiological/neurophysiological findings etc). Additionally, each sample that is sent for testing should be accompanied by a detailed patient case history and family history, to allow the laboratory specialist to make a reliable evaluation of the results that might include indications for other potential investigations.

Before considering specific analyses (enzymatic and/or molecular), preliminary screening tests should be performed (Table 1). Increased urinary excretion of glycosaminoglycans is mainly found in the mucopolysaccharidoses group, while abnormal urinary oligosaccharide excretion patterns mostly characterise the oligosaccharidoses (glycoproteinoses). There are also more specific preliminary tests, such as the qualitative assessment of urinary sulphatide storage, which can give indications for MLD (due to arylsulphatase A enzyme deficiency or saposin B activator defect); increased urinary excretion of free sialic acid is suggestive of the sialic acid storage disorders (the severe infantile form [ISSD] or the slowly progressive adult form [Salla]). Abnormal serum levels of metabolites/proteins can be used as ancillary tests in some LSDs. Serum creatine kinase (CK) concentrations can be elevated in Pompe disease, while high levels of chitotriosidase can indicate Gaucher disease and, to a lesser extent, other lipidoses, such as Niemann-Pick C (NPC). All of these preliminary (urine and serum) tests carry the risk of producing false positives/negatives, however, and need to be followed up with specific enzymatic and/or molecular analyses performed on suitable samples, leucocytes and/or cell lines (fibroblasts and/or lymphoblasts).

As about 75 per cent of LSDs are due to a deficiency in lysosomal hydrolase activity, the demonstration of reduced/absent lysosomal hydrolase activity by a specific enzyme assay is an effective and reliable method of diagnosis. In these cases, molecular analysis can refine the enzymatic diagnosis. The remaining LSDs, resulting from non-enzymatic protein defects, require molecular analysis to be performed on the specific gene for a conclusive diagnosis (Table 1).

Generally, an inherited deficiency of a lysosomal enzyme is associated with an LSD. There are, however, individuals who show greatly reduced enzyme activity but remain clinically healthy. This condition, termed as enzymatic 'pseudodeficiency' (Pd), is known in some lysosomal hydrolases. Conversely, there are circumstances in which affected individuals with a clinical/paraclinical picture resembling some glycosphingolipidoses show normal activity of the relevant lysosomal enzyme. These patients should be investigated for a potential defect of an activator protein involved in glycosphingolipid breakdown.

Pseudodeficiency

To date, Pds due to polymorphic genetic variants, have been reported for at least nine lysosomal enzymes, including: arylsulphatase A (ARSA gene),[38] β-hexosaminidase (HEXA gene),[39] α-iduronidase (IDUA gene),[40] α-glucosidase (GAA gene),[41] α-galactosidase (GLA gene),[42,43] β-galactosidase (GLB1 gene),[44] a-fucosidase (FUCA1 gene)[45] and β-glucuronidase (GUSB gene) [46,47].

While some of these genetic conditions are rare, the arylsulphatase A Pd has been estimated to have a frequency of 7.3-15 per cent [48-50]. Since the Pd allele is more frequent than the alleles causing MLD (estimated to be 0.5 per cent), individuals presenting with neurological symptoms and homozygous for arylsulphatase A Pd are likely to be misdiagnosed as MLD [51]. Additionally, it should be noted that Pd polymorphisms can occur on the same gene as MLD-causing mutations. It is therefore necessary to perform a combination of enzymatic and molecular analyses to determine the actual genetic make-up of MLD patients and their family members, in order to distinguish individuals carrying Pd alleles from those carrying MLD alleles.

Activator proteins

Another complication that can potentially lead to missed diagnoses is represented by defects of those cofactors (mentioned above) required for the function of certain lysosomal enzymes involved in glycosphingolipid breakdown. Variant forms of GM2 gangliosidosis, Krabbe disease, MLD and Gaucher disease can result not only from a deficiency of an enzymatic activity, but also from defects of sphingolipid activator proteins or saposins [52]. In these cases, conclusive diagnosis requires a comprehensive evaluation based on a range of diagnostic procedures, including neuroradiological, neurophysiological, biochemical/enzymatic and molecular tests [53].

Biochemical genetic testing

Biochemical genetic testing (BGT), including the assay of enzymatic proteins, is feasible for most LSDs and is essential for the diagnosis of primary lysosomal enzyme deficiency.

Lysosomal enzymes are present in almost all tissues and biological samples. The choice of the sample type to be analysed is based on (i) the level of an enzyme's activity in a specific tissue, (ii) the sample stability during its transfer to the referring laboratory and (iii) the time of diagnosis.

Although enzyme activity can be assayed in some biological fluids, such as plasma, serum and urine, several enzymatic Pds have been reported in serum or plasma, so their use can lead to pitfalls in diagnosis [43,54].

Leucocytes are often appropriate biological samples, although possible interference between isoenzymes should be taken into consideration. Fibroblast samples represent the gold standard in diagnosis, since they express the optimum enzyme activity; however, they require an invasive skin biopsy and culturing. Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B-lymphoblast culture obtained from a non-invasive blood sampling can be useful, bearing in mind, however, that lymphoblasts do not express some enzymatic activities, such as arylsulphatase A. Lysosomal enzyme assays are usually performed using synthetic (fluorimetric or colorimetric) substrates showing undetectable or very low enzyme activity in cell lines of affected individuals.

The complete absence of lysosomal enzyme activity generally confirms diagnosis. Conversely, the presence of normal lysosomal enzyme activity cannot exclude a specific diagnosis if it is accompanied by suggestive clinical symptoms and/or the abnormal presence of metabolites in the urine and/or storage in peripheral smear and/or tissue biopsy. For example, a patient who presents with a clinical profile resembling Gaucher disease, with high levels of chitotriosidase activity and increased concentrations of glucosylceramide in plasma and normal β-glucosidase activity in skin fibroblasts, should be referred for a molecular genetic study of the prosaposin gene (PSAP), which codes for the cofactor Sap C required for the function of β-glucosidase [55]. Findings of normal arylsulphatase A activity and abnormal patterns of urinary sulphatides in a suspected MLD patient do not exclude the disease and should be followed up by the molecular analysis of PSAP [52,53]. The detection of residual lysosomal enzyme activity should be carefully evaluated, together with clinical and instrumental findings. Molecular genetic testing (MGT) can reveal polymorphisms that potentially lead to an enzymatic Pd.

Molecular genetic testing

MGT performed on DNA and/or RNA comprises a range of different molecular approaches for investigating the entire gene-coding regions and exonintron boundaries, as well as 5'- and 3'-untranslated regions (UTRs). It can confirm the enzymatic diagnosis of an LSD, and is essential for the definitive diagnosis of LSDs resulting from non-enzymatic lysosomal proteins (Table 1) and in post-mortem diagnoses when the only suitable specimens available are DNA samples. MGT can also contribute to elucidating the findings of high biochemical residual enzyme activity in affected patients and very low enzyme activities in unaffected patients (enzymatic Pds) [38-47]. Moreover, it is useful in genotype-phenotype correlation studies for some diseases and for indentifying at-risk family members.

MGT can clarify the type of genetic variation and its impact on the protein and on the presence of residual enzyme activity. This information is crucial in evaluating treatment options, such as enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), to date only available for some disorders, and alternative treatments such as pharmacological chaperones or substrate reduction therapy (SRT), for which clinical trials are still in progress [56,57].

Particular care should be taken when interpreting genotype-phenotype correlations, even in the context of a recurrent mutation, as some patients carrying the same lesion may present with different clinical phenotypes, suggesting that other factors, such as polymorphic variants, genetic modifiers or RNA editing-like mechanisms,[58] can lead to changes in protein function which could influence the clinical phenotype.

In general, the interpretation of a molecular result should depend on a comprehensive evaluation that includes related clinical, paraclinical and biochemical data. For instance, additional molecular studies are needed in the case of an ascertained enzymatic deficiency that is not supported by the detection of the underlying genetic lesion in a patient with a picture suggestive of an LSD. Expression gene profiling and RNA and/or protein analyses can be helpful in revealing deletions/insertions, gross rearrangements and potential transcription defects. This could be the case in patients affected by X-linked Fabry diseases in which no mutations have been identified by traditional MGT on DNA samples. RNA analysis and real-time polymerase chain reaction have revealed an unbalanced α-galactosidase A mRNAs ratio of two unexpected alternatively spliced mRNAs, which resulted in the successive identification of a new intronic lesion affecting transcription and new pathogenetic mechanisms of Fabry disease [59,60].

The detection of a known mutation should also be supported by a comparison of the patient's biochemical and clinical data with those available in the literature. For instance, a genotype-phenotype miscorrelation could signal incorrect genotyping. Reports of an additional nucleotide change in cis on a mutated allele, which potentially modifies the phenotype, are not infrequent. A somatic mosaicism was reported to be the underlying molecular mechanism for an unexpectedly severe form of Gaucher disease (type 2) in a patient in whom the beneficial effect of the mild p.N409S (traditionally named as N370S) mutation was experimentally demonstrated to be reversed by the in cis presence of the severe p.L483P (traditionally named as L444P) mutation [61]. A modulating action was also reported for a novel polymorphism (p.L436F), identified in cis with the known p.R201C mutation, in a patient affected by the juvenile form of GM1 gangliosidosis with a severe outcome. In vitro expression studies and Western blot analysis showed that the novel polymorphism dramatically abrogated the residual enzyme activity predicted to be associated with the common p.R201C mutation, explaining the severe outcome [62].

Conventional MGT techniques have also been reported to be responsible for accidental misgenotyping of patients in cases of genomic lesions such as insertion/deletions, complex rearrangements and uniparental disomy. In particular, additional techniques were necessary to ascertain various gene-pseudogene rearrangements in Hunter syndrome patients which had been missed by conventional methods [63]. Partial/total gene deletions and various gene-pseudogene rearrangements led to incorrect genotyping in Gaucher disease during routine diagnostic mutation analysis [64,65].

Finally, it is important to underline that MGT results should be interpreted with caution, even in the presence of a change previously reported as a disease-causing mutation. For years, the c.1151G > A (p.S384N) mutation was considered to be disease-causing in patients with Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome but, recently, segregation studies in a family at risk for the syndrome conclusively revealed c.1151G > A (p.S384N) to be a polymorphism [66].

Screening tests on dried blood spot specimens

The availability of analyses of acylcarnitines and amino acids using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry technology on dried blood spot specimens (DBS) led to screening for treatable inborn errors of metabolisms (IEM) in newborns. At present, the expanded newborn screening based on DBS identifies more then 30 IEM and represents an important step forward [67].

A few years ago, screening tests for several LSDs by BGT on DBS using fluorescent methods[68-70]were reported. Subsequently, multiplex assays of lysosomal enzymes on DBS by tandem mass spectrometry have been described [71-73].

The availability of multiplex technology has facilitated the technical aspects of testing, making it easier to identify LSDs and to introduce newborn screening programmes for treatable LSDs [74,75].A DBS control quality for these tests has recently been developed [76].Attempts to widen screening programmes to include other LSDs are essential for patients in whom an early and presymptomatic diagnosis can provide better outcomes by reducing clinically significant disabilities [77].

Obviously, reduced residual enzyme activity detected in a presymptomatic patient at newborn screening also should be investigated by standard laboratory diagnostic procedures.

Genetic counselling

All LSDs are inherited as autosomal recessive traits, except for Fabry disease, Hunter syndrome (or mucopolysaccharidosis II) and Danon disease. These are X-linked disorders.

Once the laboratory diagnosis (enzymatic and/or molecular) of an LSD patient is ascertained, genetic counselling for at-risk couples includes prenatal testing on chorionic villi (at 11-12 weeks) or amniocytes (at 16 weeks). Genotyping individual LSD patients also allows carriers in the family to be identified and can sometimes predict phenotypes in the patients.

Biobanking

Sample and clinical/instrumental data banking is important for all rare genetic diseases--including LSDs--which often lead to death at an early age. Since it is likely that our understanding of genes, diseases and testing methodology will improve in the future, consideration should be given to biobanking appropriate biological material from patients affected or suspected to be affected by LSDs, as well as from their parents and other first-degree relatives, for future diagnostic and research purposes.

Biological material such as urine, whole blood, plasma, serum, leucocytes, DNA and cell lines (fibroblasts from skin biopsy and/or lymphoblasts from blood) should be stored. Effective interaction between clinicians and biobank staff is essential, since future results rely not only on the availability of appropriate biological samples, but also on the accurate recording of associated clinical/paraclinical data.

Hydrops foetalis, an extreme presentation of many LSDs, represents the best example of a complex case in which diagnosis can be achieved only if appropriate samples are stored. Indeed, hydrops foetalis can be associated with a wide spectrum of phenotypes, including mucopolysaccharidosis VII and IVA, Gaucher disease, sialidosis, GM1 gangliosidosis, galactosialidosis, ISSD, Niemann-Pick disease type C (and A), mucolipidosis II (I-cell disease), Wolman disease and disseminated lipogranulomatosis (Farber disease) [78].Frequently, these LSDs are only recognised after the recurrence of hydrops foetalis in several pregnancies [79,80].In order to arrive at a conclusive diagnosis and to optimise the storage of the most appropriate biological material in such complex cases, many skilled experts, including clinicians, genetics, biochemists, molecular biologists etc, must cooperate.

Conclusions

In conclusion, BGT and MGT must be considered as complementary analyses for the diagnosis of most LSDs, for genotype-phenotype correlations and for prenatal diagnosis. MGT is essential for carrier detection, and can sometimes predict prognosis and support therapeutic choices, including the application of new therapeutic approaches.

References

- Tay W. Symmetrical changes in the region of the yellow spot in each eye of an infant. Trans Opthalmol Soc. 1881;1:55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs B. On arrested cerebral development with special reference to cortical pathology. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1887;14:541–554. [Google Scholar]

- Gaucher PCE. De l'epithelioma primitif de la rate, hypertrophie idiopathique de la rate sans leucemie. Academic thesis, Paris, France. 1882.

- Capper A, Epstein H, Schless RA. Gaucher's disease. Report of a case with presentation of a table differentiating the lipoid disturbances. Am J Med Sci. 1934;188:84. doi: 10.1097/00000441-193407000-00012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hers HG. Alpha-glucosidase activity in generalized glycogen storage disease (Pompe's disease) Biochem J. 1963;86:11. doi: 10.1042/bj0860011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballabio A, Gieselmann V. Lysosomal disorders: From storage to cellular damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:684–696. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wraith JE. Lysosomal disorders. Semin Neonatol. 2002;7:75–83. doi: 10.1053/siny.2001.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futerman AH, van Meer G. The cell biology of lysosomal storage disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:554–565. doi: 10.1038/nrm1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellodi A. Lysosomal storage disorders. Br J Haematol. 2005;128:413–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitner EB, Platt FM, Futerman AH. Common and uncommon pathogenic cascades in lysosomal storage diseases. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20423–20427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.134452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boot RG, Renkema H, Verhoek M, Strijland A. et al. The human chitotriosidase gene. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25680–25685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Duve C, Wattiaux R. Functions of lysosomes. Annu Rev Physiol. 1966;28:435–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.28.030166.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield FR, McGraw TE. Endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman S, Neufeld EF. A hypothesis for I-cell disease: Defective hydrolases that do not enter lysosomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;49:992–999. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(72)90310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitman ML, Kornfeld S. UDP-N-acetylglucosamine: glycoprotein N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphotransferase. Proposed enzyme for the phosphorylation of the high mannose oligosaccharide units of lysosomal enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:4275–4281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waheed A, Hasilik A, von Figura K. Processing of the phosphorylated recognition marker in lysosomal enzymes. Characterization and partial purification of a microsomal alpha-N-acetylglucosaminyl phosphodiesterase. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:5717–5721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek D, Schwake M, Schröder J, Hughes H. et al. LIMP-2 is a receptor for lysosomal mannose-6-phosphate-independent targeting of beta-glucocerebrosidase. Cell. 2007;131:770–783. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler E, Grabowski G. In: The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8. Scriver CR, et al, editor. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY; 2001. Gaucher disease; pp. 3635–3668. [Google Scholar]

- Vallance H, Ford J. Carrier testing for autosomal-recessive disorders. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2003;40:473–497. doi: 10.1080/10408360390247832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvio M, Autio S, Louhiala P. Early clinical symptoms and incidence of aspartylglucosaminuria in Finland. Acta Paediatr. 1993;82:587–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santavuori P. Neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses in childhood. Brain Dev. 1988;10:80–83. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(88)80075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelakakis H, Dimitriou E, Tsagaraki S, Giouroukos S. et al. Lysosomal storage diseases in Greece. Genet Couns. 1995;6:43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorthuis BJ, Wevers RA, Kleijer WJ, Groener JE. et al. The frequency of lysosomal storage diseases in The Netherlands. Hum Genet. 1999;105:151–156. doi: 10.1007/s004399900075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ, Clague AE, Carey WF. Prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders. JAMA. 1999;281:249–254. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto R, Caseiro C, Lemos M, Lopes L. et al. Prevalence of lysosomal storage diseases in Portugal. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:87–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poupětová H, Ledvinová J, Berná L, Dvoráková L. et al. The birth prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders in the Czech Republic: Comparison with data in different populations. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33:387–396. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9093-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalanko A, Braulke T. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:697–709. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma MP, Pepe S, Annunziata I, Newbold RF. et al. The multiple sulfatase deficiency gene encodes an essential and limiting factor for the activity of sulfatases. Cell. 2003;113:445–456. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierks T, Schmidt B, Borissenko LV, Peng J. et al. Multiple sulfatase deficiency is caused by mutations in the gene encoding the human Cα-formylglycine generating enzyme. Cell. 2003;113:435–444. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00347-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Azzo A, Andria G, Strisciuglio P, Galjaard H. In: The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Diseases. 8. Scriver CR, et al, editor. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY; 2001. Galactosialidosis; pp. 3811–3826. [Google Scholar]

- Conzelmann E, Sandhoff K. Partial enzyme deficiencies: Residual activities and the development of neurological disorders. Dev Neurosci. 1983;6:58–71. doi: 10.1159/000112332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien JS, Kretz KA, Dewji N, Wenger DA. et al. Coding of two sphingolipid activator proteins (SAP-1 and SAP-2) by same genetic locus. Science. 1988;41:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.2842863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel R, Bach G, Sury V, Mengistu G. et al. A mutation in the saposin A coding region of the prosaposin gene in an infant presenting as Krabbe disease: First report of saposin A deficiency in humans. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;84:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger DA, De Gala G, Williams C, Taylor HA. et al. Clinical, pathological, and biochemical studies on an infantile case of sulfatide/GM1 activator protein deficiency. Am J Med Genet. 1989;33:255–265. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320330223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christomanou H, Chabas A, Pampols T, Guardiola A. Activator protein deficient Gaucher's disease. A second patient with the newly identified lipid storage disorder. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1989;67:999–1003. doi: 10.1007/BF01716064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradova V, Smid F, Ulrich-Bott B, Roggendorf W. et al. Prosaposin deficiency: Further characterization of the sphingolipid activator protein-deficient sibs. Multiple glycolipid elevations (including lactosylceramidosis), partial enzyme deficiencies and ultrastructure of the skin in this generalized sphingolipid storage disease. Hum Genet. 1993;92:143–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00219682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld S, Sly WS. In: The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Diseases. 8. Scriver CR, et al, editor. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY; 2001. I-cell disease and pseudo-Hurler polydystrophy: Disorders of lysosomal enzyme phosphorylation and localization; pp. 3469–3505. [Google Scholar]

- Gieselmann V, Polten A, Kreysing J, von Figura K. Arylsulfatase A pseudodeficiency: Loss of a polyadenylation signal and N-glycosylation site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9436–9440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Petroulakis E, Salo T, Triggs-Raine B. Benign HEXA mutations, C739T(R247W) and C745T(R249W), cause betahexosaminidase A pseudodeficiency by reducing the alpha-subunit protein levels. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14975–14982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronovich EL, Pan D, Whitley CB. Molecular genetic defect underlying alpha-L-iduronidase pseudodeficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:75–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto J, Inui K, Okada S, Ishigami W. et al. A family with pseudodeficiency of acid alpha-glucosidase. Clin Genet. 1988;33:254–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1988.tb03446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froissart R, Guffon N, Vanier MT, Desnick RJ. et al. Fabry disease: D313Y is an alpha-galactosidase A sequence variant that causes pseudodeficient activity in plasma. Mol Genet Metab. 2003;80:307–314. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7192(03)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann B, Georg Koch H, Schweitzer-Krantz S, Wendel U. et al. Deficient alpha-galactosidase A activity in plasma but no Fabry disease -- A pitfall in diagnosis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:1276–1277. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gort L, Santamaria R, Grinberg D, Vilageliu L. et al. Identification of a novel pseudodeficiency allele in the GLB1 gene in a carrier of GM1 gangliosidosis. Clin Genet. 2007;72:109–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wauters JG, Stuer KL, Elsen AV, Willems PJ. α-L-fucosidase in human fibroblasts. I. The enzyme activity polymorphism. Biochem Genet. 1992;30:131–141. doi: 10.1007/BF02399704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabas A, Giros ML, Guardiola A. Low β-glucuronidase activity in a healthy member of a family with mucopolysaccharidosis VII. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1991;14:908–914. doi: 10.1007/BF01800472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort R, Islam MR, Sly W, Chabas A. et al. A pseudo-deficiency allele (D152N) of the human beta-glucuronidase gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:798–804. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieselmann V. An assay for the rapid detection of the arylsulfatase A pseudodeficiency allele facilitates diagnosis and genetic counseling for metachromatic leukodystrophy. Hum Genet. 1991;86:251–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00202403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabás A, Castellvi S, Bayés M, Balcells S. et al. Frequency of the arylsulphatase A pseudodeficiency allele in the Spanish population. Clin Genet. 1993;44:320–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1993.tb03908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regis S, Filocamo M, Stroppiano M, Corsolini F. et al. Molecular analysis of the arylsulfatase A gene in late infantile metachromatic leukodystrophy patients and healthy subjects from Italy. J Med Genet. 1996;33:251–252. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.3.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen N, Li ZG, Waye JS, Francis G. et al. Complications in the genotypic molecular diagnosis of pseudoarylsulfatase A deficiency. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:631–637. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320450523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhoff K, Kolter T, Harzer K. In: The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Diseases. 8. Scriver CR, et al, editor. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY; 2001. Sphingolipid activator proteins; pp. 3371–3388. [Google Scholar]

- Grossi S, Regis S, Rosano C, Corsolini F. et al. Molecular analysis of ARSA and PSAP genes in twenty-one Italian patients with metachromatic leukodystrophy: Identification and functional characterization of 11 novel ARSA alleles. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:E220–E230. doi: 10.1002/humu.20851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GH. "Pseudodeficiencies" of lysosomal hydrolases. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;54:934–940. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tylki-Szymańska A, Czartoryska B, Vanier MT, Poorthuis BJ. et al. Non-neuronopathic Gaucher disease due to saposin C deficiency. Clin Genet. 2007;72:538–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parenti G. Treating lysosomal storage diseases with pharmacological chaperones: From concept to clinics. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:268–279. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffmann R. Therapeutic approaches for neuronopathic lysosomal storage disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33:373–379. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lualdi S, Tappino B, Di Duca M, Dardis A. et al. Enigmatic in vivo iduronate-2-sulfatase (IDS) mutant transcript correction to wild-type in Hunter syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:1261–1285. doi: 10.1002/humu.21356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii S, Nakao S, Minamikawa-Tachino R, Desnick RJ, Alternative splicing in the alpha-galactosidase A gene: Increased exon inclusion results in the Fabry cardiac phenotype. 2002. pp. 994–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Filoni C, Caciotti A, Carraresi L, Donati MA. et al. Unbalanced GLA mRNAs ratio quantified by real-time PCR in Fabry patients' fibroblasts results in Fabry disease. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:1311–1317. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filocamo M, Bonuccelli G, Mazzotti R, Corsolini F. et al. Somatic mosaicism in a patient with Gaucher disease type 2: Implication for genetic counselling and therapeutic decision-making. Blood Cell Mol Dis. 2000;26:611–612. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2000.0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caciotti A, Bardelli T, Cunningham J, D'Azzo A. et al. Modulating action of the new polymorphism L436F detected in the GLB1 gene of a type-II GM1 gangliosidosis patient. Hum Genet. 2003;113:44–50. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0930-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lualdi S, Regis S, Di Rocco M, Corsolini F. et al. Characterization of iduronate-2-sulfatase gene-pseudogene recombinations in eight patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type II revealed by a rapid PCR-based method. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:491–497. doi: 10.1002/humu.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayebi N, Stubblefield BK, Park JK, Orvisky E. et al. Reciprocal and nonreciprocal recombination at the glucocerebrosidase gene region: Implications for complexity in Gaucher disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:519–534. doi: 10.1086/367850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filocamo M, Regis S, Mazzotti R, Parenti G. et al. A simple non-isotopic method to show pitfalls during mutation analysis of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Med Genet. 2001;38:E34. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.10.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanetti A, Ferraresi E, Picci L, Filocamo M. et al. Segregation analysis in a family at risk for the Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome conclusively reveals c.1151G > A (p.S384N) as to be a polymorphism. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:1160–1164. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehotay DC, Hall P, Lepage J, Eichhorst JC. et al. LC-MS/MS progress in newborn screening. Clin Biochem. 2010;44:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamoles NA, Blanco M, Gaggioli D. Fabry disease: Enzymatic diagnosis in dried blood spots on filter paper. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;308:195–196. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(01)00478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamoles NA, Blanco M, Gaggioli D, Casentini C. Gaucher and Niemann-Pick diseases -- Enzymatic diagnosis in dried blood spots on filter paper: Retrospective diagnoses in newborn-screening cards. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;317:191–197. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(01)00798-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamoles NA, Blanco MB, Gaggioli D, Casentini C. Hurler-like phenotype: Enzymatic diagnosis in dried blood spots on filter paper. Clin Chem. 2001;47:2098–2102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelb MH, Turecek F, Scott CR, Chamoles NA. Direct multiplex assay of enzymes in dried blood spots by tandem mass spectrometry for the newborn screening of lysosomal storage disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006;29:397–404. doi: 10.1007/s10545-006-0265-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Scott CR, Chamoles NA, Ghavami A. et al. Direct multiplex assay of lysosomal enzymes in dried blood spots for newborn screening. Clin Chem. 2004;50:1785–1796. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.035907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Marca G, Casetta B, Malvagia S, Guerrini R. et al. New strategy for the screening of lysosomal storage disorders: The use of theonline trapping-and-cleanup liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;1:6113–6121. doi: 10.1021/ac900504s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM. Screening for lysosomal storage disorders -- A clinical perspective. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006;29:405–408. doi: 10.1007/s10545-006-0246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XK, Elbin CS, Chuang WL, Cooper SK. et al. Multiplex enzyme assay screening of dried blood spots for lysosomal storage disorders by using tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2008;54:1725–1728. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.104711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus VR, Zhang XK, Keutzer J, Bodamer OA. et al. Development and evaluation of quality control dried blood spot materials in newborn screening for lysosomal storage disorders. Clin Chem. 2009;55:158–164. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.111864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dajnoki A, Mühl A, Fekete G, Keutzer J. et al. Newborn screening for Pompe disease by measuring acid alpha-glucosidase activity using tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2008;54:1624–1629. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.107722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooper AJ, Janssens PM, de Groot AN, Liebrand-van Sambeek ML. et al. Lysosomal storage diseases in non-immune hydrops fetalis pregnancies. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;371:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malvagia S, Morrone A, Caciotti A, Bardelli T. et al. New mutations in the PPBG gene lead to loss of PPCA protein which affects the level of the beta-galactosidase/neuraminidase complex and the EBP-receptor. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;82:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froissart R, Cheillan D, Bouvier R, Tourret S. et al. Clinical, morphological, and molecular aspects of sialic acid storage disease manifesting in utero. J Med Genet. 2005;42:829–836. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.029744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]