The overall survival of patients treated with 3 mg/kg ipilimumab was compared with those given alternative systemic therapies in pretreated unresectable stage III or IV melanoma patients. The overall survival times seen with ipilimumab are expected to be greater than those with alternative systemic therapies.

Keywords: Melanoma, Ipilimumab, Survival, Network meta analysis

Abstract

Objective.

To compare the overall survival (OS) of patients treated with 3 mg/kg ipilimumab versus alternative systemic therapies in pretreated unresectable stage III or IV melanoma patients.

Methods.

A systematic literature search was performed to identify relevant randomized clinical trials. From these trials, Kaplan–Meier survival curves for each intervention were digitized and combined by means of a Bayesian network meta-analysis (NMA) to compare different drug classes.

Results.

Of 38 trials identified, 15 formed one interlinked network by drug class to allow for an NMA. Ipilimumab, at a dose of 3 mg/kg, was associated with a greater mean OS time (18.8 months; 95% credible interval [CrI], 15.5–23.0 months) than single-agent chemotherapy (12.3 months; 95% CrI, 6.3–28.0 months), chemotherapy combinations (12.2 months; 95% CrI, 7.1–23.3 months), biochemotherapies (11.9 months; 95% CrI, 7.0–22.0 months), single-agent immunotherapy (11.1 months; 95% CrI, 8.5–16.2 months), and immunotherapy combinations (14.1 months; 95% CrI, 9.0–23.8 months).

Conclusion.

Results of this NMA were in line with previous findings and suggest that OS with ipilimumab is expected to be greater than with alternative systemic therapies, alone or in combination, for the management of pretreated patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma.

Introduction

The global incidence of melanoma is on the rise, with 132,000 new cases each year estimated by the World Health Organization and an associated 46,000 deaths from melanoma worldwide [1, 2]. In the U.S., melanoma of the skin is the most common type of skin cancer, with about 68,130 patients diagnosed and 8,700 deaths in 2010 [3]. Although only 4% of melanoma patients present with advanced disease at their first diagnosis, the median overall survival (OS) time for patients with metastatic melanoma is in the range of 6–9 months [3–5]. The largest meta-analysis of historical data (2,100 patients, 42 phase II studies), by Korn et al. [6], found a median OS time of 6.2 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.9–6.5 months) and 1-year survival rate of 25.5% (95% CI, 23.6%–27.4%) for both pretreated and untreated stage IV melanoma patients. Furthermore, Howlader et al. [7] suggested that 5-year survival for patients with metastasized melanoma was <16%, whereas others estimated this proportion to be <5% as the cancer spreads to distant sites [3, 8].

In the past 40 years, ∼30 phase III trials of different agents have failed to show an OS benefit in patients with advanced melanoma [9–12]. In the absence of approved treatment beyond first-line systemic therapy, enrolment in a clinical trial has remained the standard of care [13, 14].

Ipilimumab—a fully human monoclonal antibody inhibiting cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 to promote antitumor activity—was evaluated for the the treatment of previously treated unresectable stage III or IV melanoma patients in a phase III trial (MDX010–20). Results showed a significantly longer survival time for patients treated with 3 mg/kg ipilimumab alone than for those treated with a glycoprotein 100 (gp100) vaccine, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.66 and median OS times of 10.1 months (95% CI, 8.0–13.8 months) and 6.4 months (95% CI, 5.5–11.5 months), respectively [15]. The most common adverse events were manifestations of ipilimumab's immunological mechanism of action and included diarrhea, rash, pruritus, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, and abdominal pain. These adverse events were considered to be generally medically manageable and usually reversible with topical and/or systemic immunosuppressants [15]. Based on the positive results from the MDX010–20 trial, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ipilimumab (Yervoy®; Bristol-Myers Squibb, Wallingford, CT) for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma on March 25, 2011 and the European Medicines Agency approved ipilimumab on July 13, 2011 as a treatment for patients with advanced (unresectable or metastatic) melanoma in adults who have received prior therapy [16, 17].

Despite the demonstrated survival benefit with ipilimumab relative to the gp100 vaccine, comparisons of ipilimumab with other systemic therapies are also of interest to inform treatment selection [18]. In the absence of head-to-head efficacy comparisons beyond the gp100 vaccine, an indirect treatment comparison, or network meta-analysis (NMA), is a powerful methodology to compare results with ipilimumab with published results of current or previously used therapies for advanced melanoma [19–27].

The objective of this study was to perform a systematic literature review and NMA to compare OS with 3 mg/kg ipilimumab with alternative therapies in the treatment of pretreated patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. A safety comparison was not performed given the poor and inconsistent reporting of adverse events across studies and the manageable safety profile of 3 mg/kg ipilimumab [15].

Methods

Search Strategy, Selection Criteria, and Data Extraction

To identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the efficacy of systemic therapies in the treatment of patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma, a systematic literature search was performed in MEDLINE®, MEDLINE®-In-Process, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. An initial search presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2011 Annual Meeting identified studies published in January 1, 1970 to April 8, 2010 [18]. The cutoff date of 1970 was chosen to ensure all relevant dacarbazine (DTIC) trials were identified. A search update was performed in early June 2011 to ensure the literature search was as recent as possible.

Key words and free text were combined to include the disease-specific search terms “skin-neoplasms” and “melanoma”; the disease-staging terms “metastatic,” “advanced,” and “stage III/3 or IV/4”; and nonproprietary drug names. Studies were restricted to RCTs for which full-text publications or conference abstracts were available in English. To complement searches, abstracts from the ASCO Annual Meetings, the European Association of Dermato-Oncology, and the European Society for Medical Oncology were screened for 2010 to June 2011 to identify recent and ongoing clinical trials. Reference lists from eligible studies and meta-analyses were also reviewed.

Abstract and full-text screening was performed based on the following selection criteria: patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma having previously received at least one treatment in the advanced/metastatic setting, RCTs (blinded or unblinded), and crossover or open-label extensions with parallel design or comparing different drug doses or schedules. Studies were eligible for review if any of the following agents were compared as monotherapies or in combination: ipilimumab, interferon-α (IFN-α/IFN-α2b), interleukin-2 (IL-2), DTIC, temolozomide, cisplatin, carboplatin, paclitaxel, fotemustine, melanoma vaccines, and placebo (or best supportive care). In order to maximize the evidence base obtained from the literature, RCTs that reported a proportion of pretreated patients in their study population were also considered for inclusion; however, trials were excluded if patients had only received prior adjuvant therapy for metastatic melanoma and if the line of therapy was unknown.

For each selected study, information on design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, age, gender, performance and M-status, presence of brain metastases, lactate dehydrogenase levels, type(s) of prior therapies received, and interventions compared were extracted. In addition, for each treatment the OS proportions over time were extracted from scanned Kaplan–Meier curves using DigitizeIt® software (share-it!, Eden Prairie, MN). These data were used for the NMA.

NMA of Survival Data

An NMA of the published Kaplan–Meier survival curves was performed for the RCTs according to Jansen [28] and Ouwens et al. [29]. With this approach, the observed data represented with the Kaplan–Meier curve of each drug class in each study was described with a survival function consisting of a scale and shape parameter. Accordingly, the difference in the survival curves of the drug classes compared in a trial can be described by differences in the scale and shape parameters. For the NMA, the differences in the scale and shape parameters of each trial were synthesized and indirectly compared across trials. As a result, we can indirectly compare multiple survival outcomes over time with drug classes not studied in a head-to-head fashion. This method does not rely on the proportional hazards assumption and as such is less prone to result in a biased comparison than indirect comparisons based on the reported constant HR [28, 29]. A Bayesian approach was used to facilitate parameter estimation of the NMA models and allow for the probabilistic interpretation of uncertainty.

NMAs and meta-analyses within the Bayesian framework involve data, a likelihood distribution, a model with parameters, and prior distributions. With a Bayesian framework, prior belief about a treatment effect is combined with a likelihood distribution that summarizes the data to obtain a posterior distribution reflecting the belief about the treatment effect after incorporating the evidence.

From the digitally scanned Kaplan–Meier curves, a dataset was created for each intervention from each trial with the number of patients at risk at the beginning of each consecutive 2-month time window as well as the number of deaths in that window. The corresponding hazard was based on a binomial likelihood distribution [28, 29]. Whenever available, the numbers of patients at risk as reported below the published Kaplan–Meier curves were used to deduct the numbers at risk for specific time windows. If this was not reported for a specific time point, it was assumed that censoring occurred before the event of interest in that window, which allowed back-calculation of the number at risk based on the reported number of patients at risk in a subsequent window. This approach resulted in conservative estimates of the precision of the analysis [28, 29].

For the analysis, fixed and random-effects Weibull and Gompertz NMA models were compared based on goodness-of-fit estimates. The goodness of fit of the model predictions to the observed data was measured by calculating the posterior mean residual deviance [30]. The deviance information criterion (DIC) provides a measure of model fit that penalizes model complexity [31]. The fixed-effects Gompertz model resulted in a lower DIC than the other models and was therefore considered the model of choice.

In order to avoid prior beliefs about the differences in survival outcomes influencing the results of the Bayesian analysis, uninformative prior distributions were used. Prior distributions of all model parameters were normal distributions with a mean of zero and a variance of 104. Model parameters were estimated using a Markov chain Monte Carlo method called Gibbs sampling as implemented in the WinBUGS software package (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK) [32].

The results of the analysis are posterior distributions of the model parameters that can be transformed into meaningful outcomes: HR for 3 mg/kg ipilimumab versus other classes as a function of time and the survival proportions over time and expected survival time (i.e., mean survival time) by treatment. The expected survival time reflects the area under the survival curve until all patients have died and can be considered a summary measure of the complete survival curve, unlike the median survival time, which ignores differences in survival proportions over time beyond the point when 50% of patients are still alive. The posterior distributions were summarized with a point estimate and a 95% credible interval (CrI), reflecting the range of true treatment effects with 95% probability. Because the posterior distribution can be interpreted in terms of probabilities, the probability that a certain treatment of all those compared provides the greatest OS probability over time was also calculated.

Results

Study Identification and Selection

The original search identified 1,793 potentially relevant (nonduplicate) study abstracts. Of the 183 publications selected for full-text review, a further 145 were excluded based on the selection criteria. A previous version of this systematic review identified 38 publications eligible for inclusion: five related to pretreated patients alone and 33 related to a mixed population (i.e., pretreated and untreated patients). One hundred twenty-nine additional citations were captured in the search update. Of these 129 abstracts, only one study was selected for review—that was previously included as an abstract [33]. One study identified in the original review was excluded from the update following contact with the author [4]. The majority of patients received prior therapy in the adjuvant setting; patients had not received prior treatment for metastatic disease. Conference Web site searches for 2008–2011 identified one additional abstract that was not superseded by a full-text publication reporting on pretreated patients. In total, 38 studies were included in this review [15, 33–69]. Only five trials enrolled 100% pretreated patients; the remainder of the evidence base included a mix of treatment-naïve and previously treated patients. It should be noted that the BRAF Inhibitor in Melanoma (BRIM)-2 study, evaluating the new agent vemurafenib in pretreated patients and presented at the ASCO 2011 Annual Meeting, was identified but did not meet the eligibility criteria for this analysis because the study was a nonrandomized trial [70].

Study Characteristics

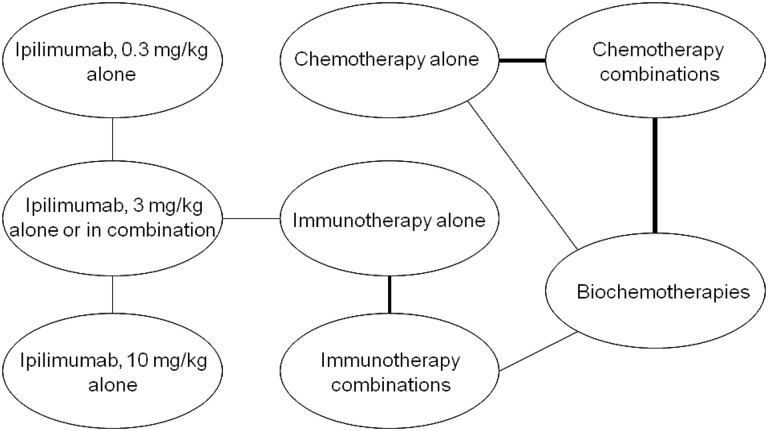

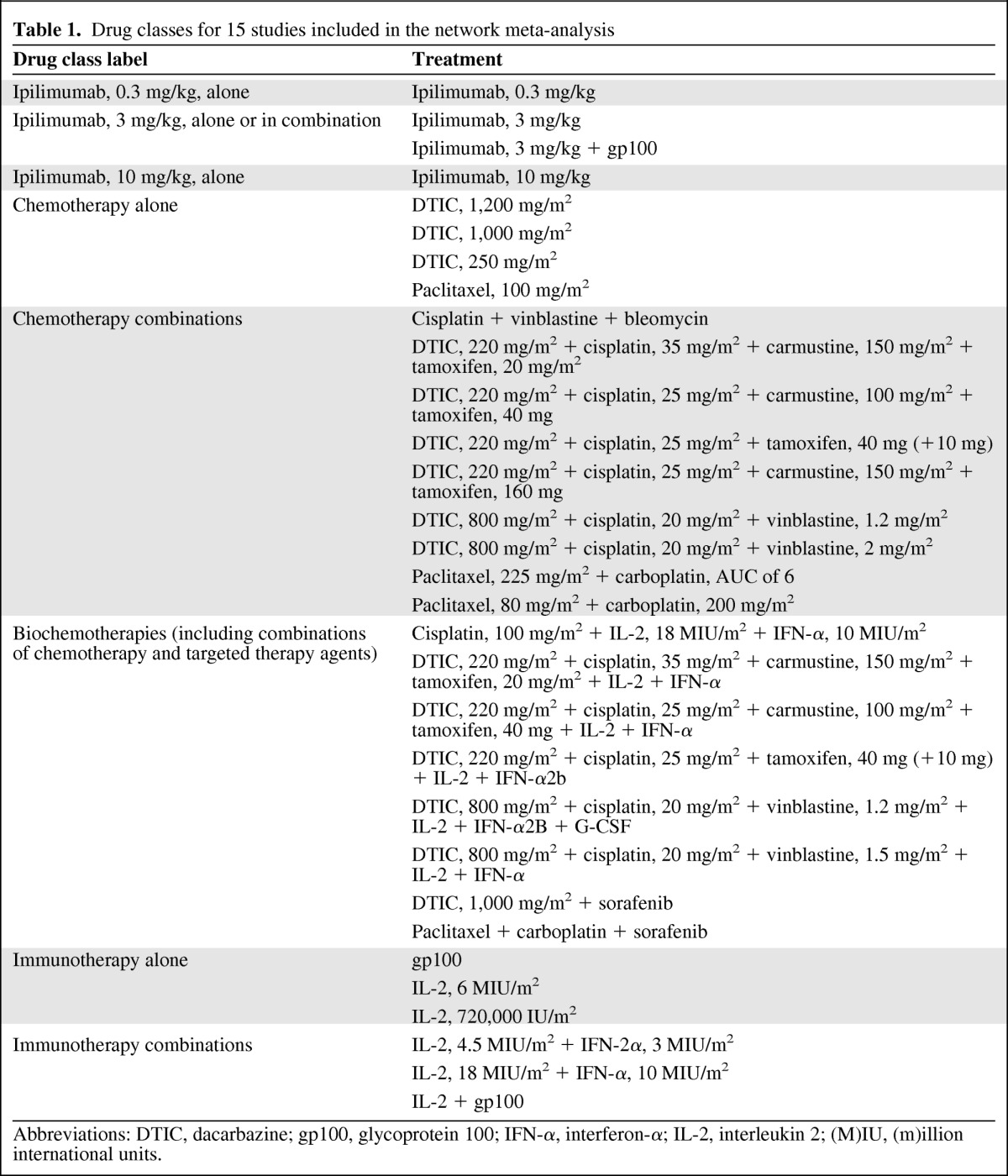

The identified studies evaluated a wide range of interventions. Trials primarily evaluated the efficacy of adding another agent, most commonly IFN-α or IL-2, to an existing or experimental treatment regimen. The majority of the evidence was came from “stand-alone” trials, meaning that the trials did not have interventions in common and therefore did not form one network of interlinked RCTs. Based on expert clinical opinion and the findings of a previous analysis by Kotapati et al. [18], treatments were grouped into eight drug classes, allowing 15 RCTs to form one interlinked network and allowing the reported Kaplan–Meier OS curves to be used in an NMA (Table 1, Fig. 1). However, comparing across classes implies that only RCTs evaluating treatments within two or more classes could be included for analysis, reducing our evidence base from 38 to 15 studies and excluding landmark trials such as that of Eisen et al. [45], which is the only RCT in patients with metastatic malignant pretreated melanoma that is placebo controlled, and as such did not provide a link with the drug classes in the other studies.

Table 1.

Drug classes for 15 studies included in the network meta-analysis

Abbreviations: DTIC, dacarbazine; gp100, glycoprotein 100; IFN-α, interferon-α; IL-2, interleukin 2; (M)IU, (m)illion international units.

Figure 1.

Network of 15 studies included in network meta-analysis based on treatment class.

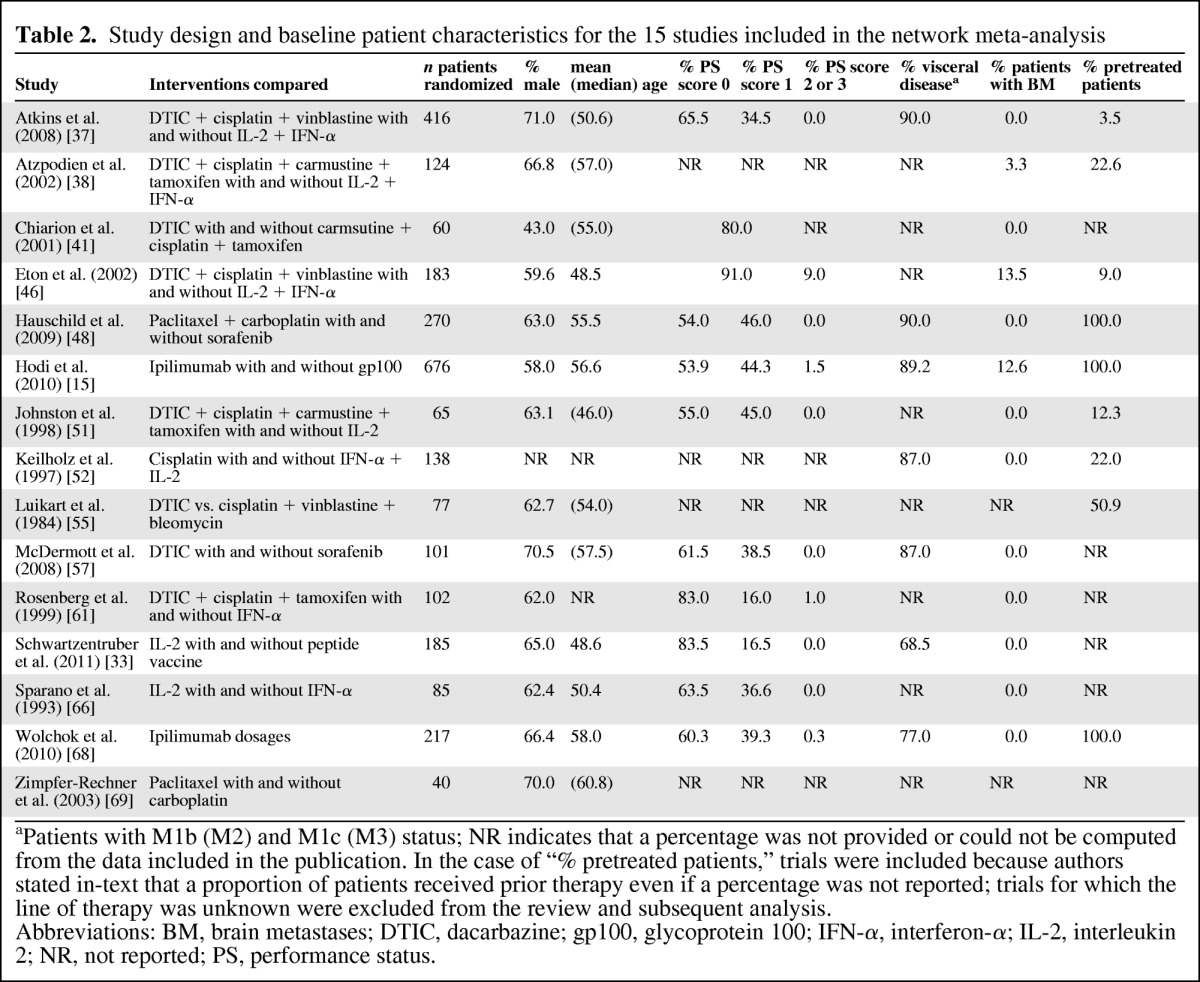

Table 2 provides an overview of the study and patient characteristics of the 15 studies included in the NMA. The supplemental online data provide information for the other 23 studies. Study populations were of broadly comparable age, gender, race, and disease severity composition, but differed with regard to previous systemic therapies received and allowance of patients with brain metastases. The type of systemic treatment received prior to second-line treatment varied substantially, and data regarding previous therapies, such as the percentage of pretreated patients and the number of lines received, were often not reported.

Table 2.

Study design and baseline patient characteristics for the 15 studies included in the network meta-analysis

aPatients with M1b (M2) and M1c (M3) status; NR indicates that a percentage was not provided or could not be computed from the data included in the publication. In the case of “% pretreated patients,” trials were included because authors stated in-text that a proportion of patients received prior therapy even if a percentage was not reported; trials for which the line of therapy was unknown were excluded from the review and subsequent analysis.

Abbreviations: BM, brain metastases; DTIC, dacarbazine; gp100, glycoprotein 100; IFN-α, interferon-α; IL-2, interleukin 2; NR, not reported; PS, performance status.

NMA

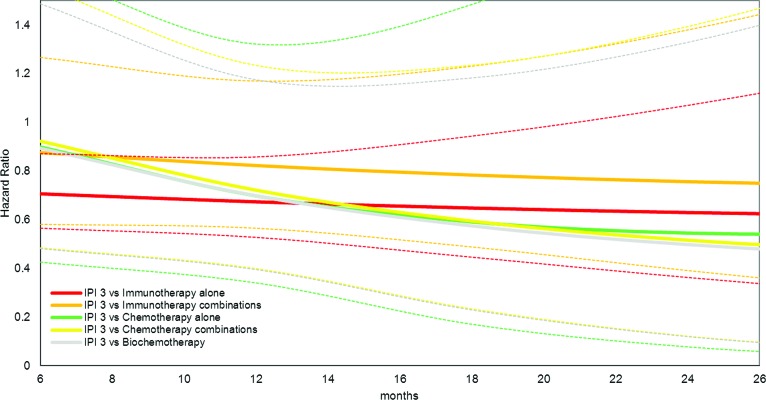

In Figure 2, the results of the NMA are reflected with HRs and associated 95% CIs of 3 mg/kg ipilimumab versus other drug classes. As reflected with an HR<1, treatment with 3 mg/kg ipilimumab is expected to result in a lower mortality rate than with other treatments. Ipilimumab's survival advantage increases over time, particularly versus chemotherapies and biochemotherapies, with HRs reaching ∼0.5. The HR for 3 mg/kg ipilimumab versus another immunotherapy alone remained relatively constant over time, at ∼0.7. It is important to note that the longer the “path” between two treatment groups in the network of Figure 1, the greater the amount of uncertainty associated with the relative effect estimate (i.e., the HR) of this pairwise comparison. If the treatments compared are more closely located in the network, then the uncertainty for a given effect estimate is smaller.

Figure 2.

Hazard ratio of 3 mg/kg ipilimumab (IPI 3) versus other drug classes, fixed effects Gompertz network meta-analysis model. Dotted lines reflect the 95% credible limits (low and high) of the same colored solid hazard ratio curves.

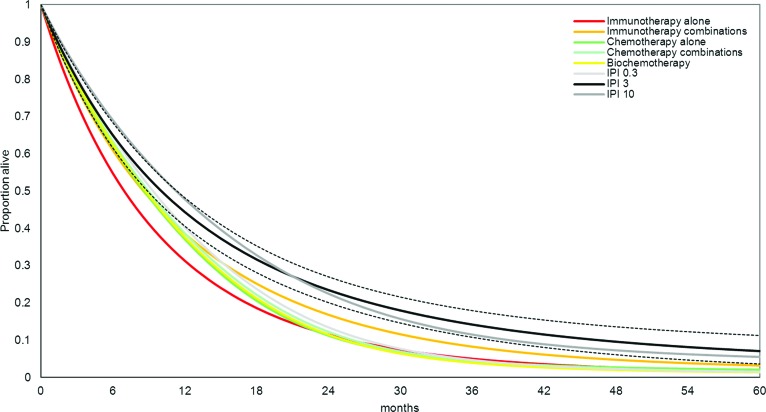

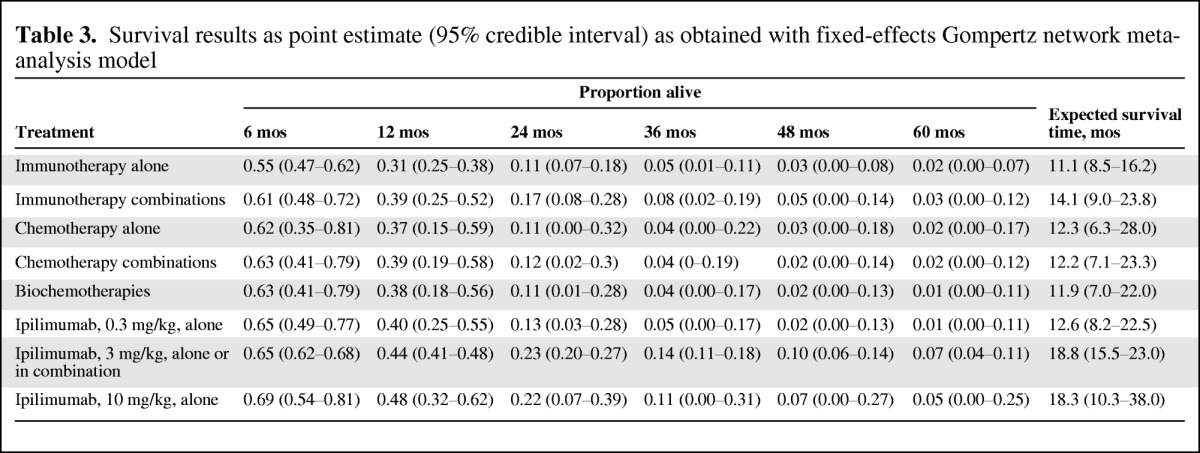

In Table 3 and Figure 3, the estimated survival proportions are mapped over time for each of the eight drug classes. At any point in time, a greater proportion of patients treated with 10 mg/kg ipilimumab and 3 mg/kg ipilimumab are expected to be alive than with all other drug classes. This corresponds to an expected survival time >18 months associated with ipilimumab in this patient population. The expected survival times with other drug classes varied in the range of 11.1–14.1 months. The corresponding median survival time estimates can be read from Figure 3 at the point when 50% of the patients are still alive.

Table 3.

Survival results as point estimate (95% credible interval) as obtained with fixed-effects Gompertz network meta-analysis model

Figure 3.

Survival probability over time as obtained with fixed-effects Gompertz network meta-analysis model. Dotted black lines reflect the 95% credible limits (low and high) of the 3 mg/kg ipilimumab (IPI 3) solid black survival curve. High and low estimates for Kaplan–Meier curves are only included for IPI 3 to ensure readability of the figure.

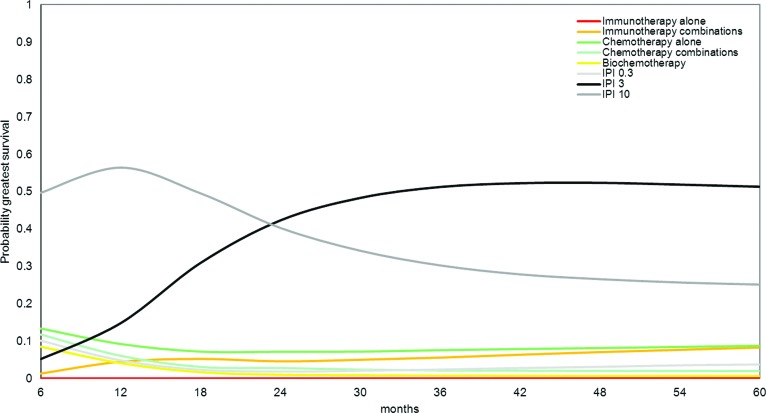

Figure 4 shows the probability that each drug class shown is the most efficacious of the eight classes at different time points. This is a reflection of the survival estimates and associated uncertainty. Patients treated with 3 mg/kg ipilimumab and 10 mg/kg ipilimumab have the greatest probability of having the greatest OS gains over time.

Figure 4.

Probability of greatest survival benefit over time with each treatment as obtained with fixed effects Gompertz network meta-analysis model.

Abbreviation: IPI, ipilimumab.

Discussion

The objective of this analysis was to compare the efficacy of ipilimumab and alternative therapies in the treatment of pretreated patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. A systematic search of the clinical literature provided an up-to-date overview of the available evidence for treatment of this disease. By grouping different treatments into drug classes, an NMA could be performed, which allowed for the comparison of the OS probabilities with ipilimumab relative to those with single-agent chemotherapy, chemotherapy combinations, biochemotherapies, single-agent immunotherapy, and immunotherapy combinations. Patients treated with 3 mg/kg ipilimumab and 10 mg/kg ipilimumab are expected to have the longest OS times than patients treated with any other drug class.

Results show the relative gain with ipilimumab in terms of the OS probability over time compared with other drug classes. HRs for ipilimumab versus other immunotherapies and chemotherapies were consistently <1 for >2 years, suggesting that patients treated with ipilimumab have a lower mortality risk than those treated with any other drug class. This translated into an expected OS time >18 months. In this pretreated patient population, no significant difference in the expected OS probabilities between 3 mg/kg ipilimumab and 10 mg/kg ipilimumab was observed. The impact of the ipilimumab dose on survival outcomes is currently being investigated in a randomized trial comparing ipilimumab administered at 3 mg/kg with ipilimumab administered at 10 mg/kg in patients with previously treated or untreated unresectable or metastatic melanoma [72]. On August 17, 2011, the FDA approved vemurafenib for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with the BRAFV600E mutation based on an RCT versus DTIC (1,000 mg/m2) [71]. However, this BRIM-3 trial was conducted in previously untreated patients, which is different from studies included in the NMA, and was therefore excluded from this analysis. In the BRIM-2 study, however, vemurafenib was evaluated in previously treated patients with the BRAFV600E mutation, which showed OS probabilities of 77% at 6 months and 58% at 1 year. Although these survival estimates may appear more favorable than those obtained with ipilimumab in the NMA, the absence of a control arm in the BRIM-2 study does not allow for a valid indirect comparison of OS between vemurafenib and ipilimumab. Without a control arm, it is unknown how much of the reported OS benefit is attributable to the efficacy of vemurafenib.

The current analysis builds upon a previous systematic review performed by Kotapati et al. [18] and presented at ASCO 2011 Annual Meeting. They performed a meta-analysis of 25 of 38 studies reviewed and reported results by treatment, rather than drug class. Because the available studies did not form one interlinked network of RCTs, an NMA by treatment was not possible. The advantage of an NMA based on a network of trials that have interventions in common is that study effects can be separated from treatment effects, thereby limiting bias in a comparison of treatment effects of interventions evaluated in different trials. As an alternative to an NMA, Kotapati et al. [18] used the risk equation of Korn et al. [6] to adjust for differences in prognostic factors across studies not linked in one network. This relies on the assumption that all differences in prognostic factors across trials, other than treatments compared, are captured by the Korn et al. [6] risk equation. Unlike the NMA approach used in the present analysis, the approach by Kotapati et al. [18] does not capture differences across studies in all measured and unmeasured prognostic factors. The analysis by Kotapati et al. [18] arguably has some limitations to comparing survival outcomes seen with different treatments. It did, however, provide reliable information to help inform the allocation of treatments into different drug classes to facilitate the NMA presented in this paper. Furthermore, it is important to note that the findings of Kotapati et al. [18] are consistent with the current analysis by the fact that that treatment with 3-mg/kg dose of ipilimumab results in the greatest OS probability estimates.

Although grouping of interventions into drug classes allowed for an NMA of a network of RCTs, thereby limiting bias in indirect comparisons caused by possible differences in study effects, a number of limitations remain. Most importantly, the current NMA relies on an appropriate classification of treatments into drug classes. If there are systematic (i.e., true) differences in OS outcomes for treatments grouped into one class, the indirect comparisons obtained with the NMA will still be biased—the HRs obtained between the different drug classes will be either over- or underestimated. Although the grouping of the treatments can be debated, results from the previously performed analysis by Kotapati et al. [18] suggest that treatments within drug classes are sufficiently homogeneous in terms of expected OS probabilities, and as such the grouping of treatment is most likely not a relevant source of bias in the NMA.

Although with an NMA of RCTs differences in prognostic factors across studies are taken into account, there is still the risk that there are systematic differences across trials. If the differences in patient (or study) characteristics across comparisons are modifiers of the relative survival probability (i.e., the HR), then the indirect or mixed relative effect estimates obtained with the NMA will be biased. The selection criteria for enrollment of patients appeared consistent for the majority of the included trials; however, some issues were identified that suggest that the included studies may not be perfectly comparable in terms of patient characteristics, particularly in terms of the presence of brain metastases and previous systemic treatment (e.g., pretreated versus a mix of pretreated and untreated patients). The question is whether or not these differences in patient characteristics are effect modifiers and sufficiently large to be considered a source of confounding bias. Possible residual bias resulting from differences in effect modifiers across comparisons can only be ruled out with access to patient-level data for all the included trials; unfortunately, these data could not be obtained.

For the systematic literature search, a cutoff date of 1970 was chosen to ensure all relevant DTIC trials were identified. As a result, the oldest trial included in the study was published in 1984, which raises the question of whether or not the older trials are representative for the comparisons performed. In the past 30 years, the evolution of clinical trials occurred in a relatively ad hoc fashion driven in part by higher response rates with combination therapies and promising data from phase II studies of immunotherapy agents. However, the standard of care for melanoma remained, until 2011, referral to a clinical trial. This resulted in many trials using different treatment approaches and a lack of a common comparator. Despite improvements in supportive care, the included studies do not show a pattern indicating better survival outcomes with active therapies used in the second-line treatment of patients with advanced melanoma prior to the pivotal phase III trial for 3 mg/kg ipilimumab (MDX010–20). As such, including older studies can be considered valid and representative of the expected OS probabilities with interventions other than 3 mg/kg ipilimumab.

For the purpose of this analysis, an RCT comparing different treatments of the same drug class does not provide relevant evidence for the comparison of drug classes. Criteria for inclusion were the availability of Kaplan–Meier curves and that RCTs needed to compare treatments of different drug classes (Table 1). Therefore, the studies included in the NMA—15 in total—might be a nonrepresentative selection of the 38 studies identified.

All these limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this analysis. That being said, the comparative survival estimates obtained with the current NMA, which are in line with the findings of Kotapati et al. [18], are the best possible given the available evidence and can be used to inform treatment choices. The treatment of patients with malignant melanoma has been changed by the recognition of BRAF mutations and the development of inhibitors of deregulated BRAF. However, the results of the current indirect comparison and previous analysis by Kotapati et al. [18] reflect the average survival benefit obtained with ipilimumab versus other treatments across the whole distribution of pretreated melanoma patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma [18]. Data are currently not available to evaluate the OS probability with ipilimumab compared with novel agents such as vemurafenib in the BRAF+ patient subgroup.

In conclusion, 3 mg/kg ipilimumab is expected to result in greater OS than other existing therapies for the management of pretreated patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma.

See www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The manuscript was previously presented, in part, as Kotapati S, Dequen P, Ouwens M et al. Overall survival (OS) in the management of pretreated patients with unresectable stage III/IV melanoma: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2011;29(15 suppl):8580.

Footnotes

- (C/A)

- Consulting/advisory relationship

- (RF)

- Research funding

- (E)

- Employment

- (H)

- Honoraria received

- (OI)

- Ownership interests

- (IP)

- Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder

- (SAB)

- Scientific advisory board

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Jeroen P. Jansen, Pascale Dequen, Mario J.N.M. Ouwens

Collection and/or assembly of data: Pascale Dequen

Data analysis and interpretation: Jeroen P. Jansen, Pascale Dequen, Paul Lorigan, Mario J.N.M. Ouwens, Srividya Kotapati

Manuscript writing: Jeroen P. Jansen, Pascale Dequen, Paul Lorigan, Marc van Baardewijk

Final approval of manuscript: Jeroen P. Jansen, Pascale Dequen, Paul Lorigan, Marc van Baardewijk, Mario J.N.M. Ouwens, Srividya Kotapati

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Skin Cancers - How Common Is Skin Cancer? [accessed August 10, 2011]. Available at http://www.who.int/uv/faq/skincancer/en/index1.html.

- 2.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwala SS. Current systemic therapy for metastatic melanoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:587–595. doi: 10.1586/era.09.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedikian AY, Millward M, Pehamberger H, et al. Bcl-2 antisense (oblimersen sodium) plus dacarbazine in patients with advanced melanoma: The Oblimersen Melanoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4738–4745. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsao H, Atkins MB, Sober AJ. Management of cutaneous melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:998–1012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korn EL, Liu PY, Lee SJ, et al. Meta-analysis of phase II cooperative group trials in metastatic stage IV melanoma to determine progression-free and overall survival benchmarks for future phase II trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:527–534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review. 1975–2008. [accessed August 8, 2011]. Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008.

- 8.Sasse AD, Sasse EC, Clark LG, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy versus chemotherapy for metastatic malignant melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD005413. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005413.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eggermont AM, Robert C. New drugs in melanoma: It's a whole new world. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2150–2157. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggermont AM, Kirkwood JM. Re-evaluating the role of dacarbazine in metastatic melanoma: What have we learned in 30 years? Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:1825–1836. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrella T, Quirt I, Verma S, et al. Melanoma Disease Site Group of Cancer Care Ontario's Program in Evidence-based Care. Single-agent interleukin-2 in the treatment of metastatic melanoma: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:484–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trinh VA. Current management of metastatic melanoma. Am J Health System Pharm. 2008;65(suppl 9):S3–S8. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Bichakjian CK, et al. NCCN Melanoma Panel. Melanoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:250–275. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dummer R, Hauschild A, Guggenheim M, et al. ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Melanoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 5):v194–v197. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA News Release: FDA Approves New Treatment for a Type of Late-Stage Skin Cancer. [accessed August 8, 2011]. Available at http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm1193237.htm.

- 17.European Medicines Agency. Yervoy (ipilimumab) [accessed November 3, 2011]. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002213/human_med_001465.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124.

- 18.Kotapati S, Dequen P, Ouwens M, et al. Overall survival (OS) in the management of pretreated patients with unresectable stage III/IV melanoma: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15 suppl):8580. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, et al. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:683–691. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lumley T. Network meta-analysis for indirect treatment comparisons. Stat Med. 2002;21:2313–2324. doi: 10.1002/sim.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salanti G, Higgins JP, Ades AE, et al. Evaluation of networks of randomized trials. Stat Methods Med Res. 2008;17:279–301. doi: 10.1177/0962280207080643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansen JP, Fleurence R, Devine B, et al. Interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis for health-care decision making: Report of the ISPOR Task Force on Indirect Treatment Comparisons Good Research Practices: Part 1. Value Health. 2011;14:417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoaglin DC, Hawkins N, Jansen JP, et al. Conducting indirect-treatment-comparisons and network-meta-analysis studies: Report of the ISPOR Task Force on Indirect Treatment Comparisons Good Research Practices: Part 2. Value Health. 2011;14:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu G, Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Med. 2004;23:3105–3124. doi: 10.1002/sim.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caldwell DM, Ades AE, Higgins JP. Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: Combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ. 2005;331:897–900. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7521.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ades AE. A chain of evidence with mixed comparisons: Models for multi-parameter synthesis and consistency of evidence. Stat Med. 2003;22:2995–3016. doi: 10.1002/sim.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salanti G, Dias S, Welton NJ, et al. Evaluating novel agent effects in multiple-treatments meta-regression. Stat Med. 2010;29:2369–2383. doi: 10.1002/sim.4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jansen JP. Network meta-analysis of survival data with fractional polynomials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouwens M, Philips Z, Jansen JP. Network meta-analysis of parametric survival curves. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1:258–271. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dempster AP. The direct use of likelihood for significance testing. Stat Comput. 1997;7:247–252. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, et al. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 2002;64:583–639. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lunn DJ, Thomas A, Best N, et al. WinBUGS—a Bayesian modelling framework: Concepts, structure, and extensibility. Stat Comput. 2000;10:325–337. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartzentruber DJ, Lawson DH, Richards JM, et al. gp100 peptide vaccine and interleukin-2 in patients with advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2119–2127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agarwala SS, Glaspy J, O'Day SJ, et al. Results from a randomized phase III study comparing combined treatment with histamine dihydrochloride plus interleukin-2 versus interleukin-2 alone in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:125–133. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agarwala SS, Ferri W, Gooding W, et al. A phase III randomized trial of dacarbazine and carboplatin with and without tamoxifen in the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 1999;85:1979–1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmann DL, Hahn RG, Bisel HF. Clinical evaluation of 5-(3,3-dimethyl-1-triazeno)imidazole-4-carboxam-ide (NSC-45388), melphalan (NSC-8806), and hydroxyurea (NSC-32065) in the treatment of disseminated malignant melanoma. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1972;56:369–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atkins MB, Hsu J, Lee S, et al. Phase III trial comparing concurrent biochemotherapy with cisplatin, vinblastine, dacarbazine, interleukin-2, and interferon alfa-2b with cisplatin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine alone in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma (E3695): A trial coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5748–5754. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atzpodien J, Neuber K, Kamanabrou D, et al. Combination chemotherapy with or without s.c. IL-2 and IFN-α: Results of a prospectively randomized trial of the Cooperative Advanced Malignant Melanoma Chemoimmunotherapy Group (ACIMM) Br J Cancer. 2002;86:179–184. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carter RD, Krementz ET, Hill GJ, 2nd, et al. DTIC (nsc-45388) and combination therapy for melanoma. I. Studies with DTIC, BCNU (NSC-409962), CCNU (NSC-79037), vincristine (NSC-67574), and hydroxyurea (NSC-32065) Cancer Treat Rep. 1976;60:601–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melanoma Study Group of the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, Celis E. Overlapping human leukocyte antigen class I/II binding peptide vaccine for the treatment of patients with stage IV melanoma: Evidence of systemic immune dysfunction. Cancer. 2007;110:203–214. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiarion Sileni V, Nortilli R, Aversa SM, et al. Phase II randomized study of dacarbazine, carmustine, cisplatin and tamoxifen versus dacarbazine alone in advanced melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2001;11:189–196. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200104000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costanza ME, Nathanson L, Schoenfeld D, et al. Results with methyl-CCNU and DTIC in metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 1977;40:1010–1015. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197709)40:3<1010::aid-cncr2820400308>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dorval T, Négrier S, Chevreau C, et al. Randomized trial of treatment with cisplatin and interleukin-2 either alone or in combination with interferon-α-2a in patients with metastatic melanoma: A Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer Multicenter, parallel study. Cancer. 1999;85:1060–1066. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1060::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Du Bois JS, Trehu EG, Mier JW, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of high-dose interleukin-2 in combination with a soluble p75 tumor necrosis factor receptor immunoglobulin G chimera in patients with advanced melanoma and renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1052–1062. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eisen T, Trefzer U, Hamilton A, et al. Results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind phase 2/3 study of lenalidomide in the treatment of pretreated relapsed or refractory metastatic malignant melanoma. Cancer. 2010;116:146–154. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eton O, Legha SS, Bedikian AY, et al. Sequential biochemotherapy versus chemotherapy for metastatic melanoma: Results from a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2045–2052. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glover D, Ibrahim J, Kirkwood J, et al. Phase II randomized trial of cisplatin and WR-2721 versus cisplatin alone for metastatic melanoma: An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study (E1686) Melanoma Res. 2003;13:619–626. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200312000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hauschild A, Agarwala SS, Trefzer U, et al. Results of a phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of sorafenib in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel as second-line treatment in patients with unresectable stage III or stage IV melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2823–2830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hersh EM, O'Day SJ, Powderly J, et al. ePub 2010) A phase II multicenter study of ipilimumab with or without dacarbazine in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced melanoma. Investig New Drugs. 2011;29:489–498. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hill GJ, 2nd, Metter GE, Krementz ET, et al. DTIC and combination therapy for melanoma. II. Escalating schedules of DTIC with BCNU, CCNU, and vincristine. Cancer Treat Rep. 1979;63:1989–1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnston SR, Constenla DO, Moore J, et al. Randomized phase II trial of BCDT [carmustine (BCNU), cisplatin, dacarbazine (DTIC) and tamoxifen] with or without interferon α (IFN-α) and interleukin (IL-2) in patients with metastatic melanoma. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:1280–1286. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keilholz U, Goey SH, Punt CJ, et al. Interferon alfa-2a and interleukin-2 with or without cisplatin in metastatic melanoma: A randomized trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Melanoma Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2579–2588. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.7.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kirkwood JM, Lee S, Moschos SJ, et al. Immunogenicity and antitumor effects of vaccination with peptide vaccine+/-granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor and/or IFN-α2b in advanced metastatic melanoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Phase II Trial E1696. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1443–1451. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koretz MJ, Lawson DH, York RM, et al. Randomized study of interleukin 2 (IL-2) alone vs IL-2 plus lymphokine-activated killer cells for treatment of melanoma and renal cell cancer. Arch Surg. 1991;126:898–903. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410310108017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luikart SD, Kennealey GT, Kirkwood JM. Randomized phase III trial of vinblastine, bleomycin, and cis-dichlorodiammine-platinum versus dacarbazine in malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:164–168. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.3.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maio M, Mackiewicz A, Testori A, et al. Large randomized study of thymosin alpha 1, interferon alfa, or both in combination with dacarbazine in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1780–1787. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.5208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDermott DF, Sosman JA, Gonzalez R, et al. Double-blind randomized phase II study of the combination of sorafenib and dacarbazine in patients with advanced melanoma: A report from the 11715 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2178–2185. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mornex F, Thomas L, Mohr P, et al. A prospective randomized multicentre phase III trial of fotemustine plus whole brain irradiation versus fotemustine alone in cerebral metastases of malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:97–103. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200302000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nicholson S, Guile K, John J, et al. A randomized phase II trial of SRL172 (Mycobacterium vaccae) +/- low-dose interleukin-2 in the treatment of metastatic malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:389–393. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200308000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O'Day S, Gonzalez R, Lawson D, et al. Phase II, randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial of weekly elesclomol plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone for stage IV metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5452–5458. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Schwartzentruber DJ, et al. Prospective randomized trial of the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma using chemotherapy with cisplatin, dacarbazine, and tamoxifen alone or in combination with interleukin-2 and interferon alfa-2b. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:968–975. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Yang JC, et al. Prospective randomized trial of high-dose interleukin-2 alone or in conjunction with lymphokine-activated killer cells for the treatment of patients with advanced cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:622–632. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.8.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rusthoven JJ, Quirt IC, Iscoe NA, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing the response rates of carmustine, dacarbazine, and cisplatin with and without tamoxifen in patients with metastatic melanoma National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2083–2090. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.7.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Slingluff C, Lee SJ, Chianese-Bullock KA, et al. First report of a randomized phase II trial of multi-epitope vaccination with melanoma peptides for cytotoxic T cells and helper T cells in patients with metastatic melanoma: An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study (E1602) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15 suppl):8508. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Slingluff CL, Jr, Petroni GR, Yamshchikov G, et al. Clinical and immunologic results of a randomized phase II trial of vaccination using four melanoma peptides either administered in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in adjuvant or pulsed on dendritic cells. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4016–4026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sparano JA, Fisher RI, Sunderland M, et al. Randomized phase III trial of treatment with high-dose interleukin-2 either alone or in combination with interferon alfa-2a in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1969–1977. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.10.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weber J, Thompson JA, Hamid O, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II study comparing the tolerability and efficacy of ipilimumab administered with or without prophylactic budesonide in patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5591–5598. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wolchok JD, Neyns B, Linette G, et al. Ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2, dose-ranging study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:155–164. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zimpfer-Rechner C, Hofmann U, Figl R, et al. Randomized phase II study of weekly paclitaxel versus paclitaxel and carboplatin as second-line therapy in disseminated melanoma: A multicentre trial of the Dermatologic Co-operative Oncology Group (DeCOG) Melanoma Res. 2003;13:531–536. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200310000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ribas A, Kim KB, Schuchter LM, et al. BRIM-2: An open-label, multicenter phase II study of vemurafenib in previously treated patients with BRAF V600E mutation-positive metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15 suppl):8509. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. BRIM-3 Study Group. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clinicaltrials.gov. Phase 3 Trial in Subjects With Metastatic Melanoma Comparing 3 mg/kg Ipilimumab Versus 10 mg/kg Ipilimumab. BMS Clinical Trials Disclosure. [accessed February 28, 2012]. Available at http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01515189.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.