This study examines evolving policies toward truth-telling in cancer diagnoses in the Arab world, through a study in Qatar.

Keywords: Cancer, Truth disclosure, Cross-cultural practice, Islamic countries

Learning Objectives

After completing this course, the reader will be able to:

Compare physician-stated and actual disclosure practices with respect to cancer diagnoses.

Identify variables that influence physician truth-telling practices with respect to cancer diagnoses.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com

Abstract

There is limited information regarding physicians' attitudes toward revealing cancer diagnoses to patients in the Arab world. Using a questionnaire informed by a seminal study carried out by Oken in 1961, our research sought to determine present-day disclosure practices in Qatar, identify physician sociodemographic variables associated with truth-telling, and outline trends related to future practice. A sample of 131 physicians was polled. Although nearly 90% of doctors said they would inform cancer patients of their diagnosis, ∼66% of respondents stated that they made exceptions to their policy, depending on patient characteristics. These data suggest that clinical practices are somewhat discordant on professed beliefs about the ethical propriety of disclosure.

Introduction

Over the past half century, evolving medical ethics has identified the patient's right to know his or her diagnosis and the physician's reciprocal duty of disclosure as key elements of the informed consent process. But what began in the U.S. and has taken deep cultural roots in medical practice there, has not been universally assimilated into medical practices and cultural norms across the globe. In this paper, we review the historical evolution of truth-telling with an emphasis on this evolving practice in the Arabic-speaking world. To that end, we offer an empirical study—and ethical analysis—of current attitudes of physicians practicing in Qatar with specific reference to the disclosure of a cancer diagnosis.

Background

“No problem is more vexing than the decision about what to tell the cancer patient,” writes Oken at the start of his groundbreaking 1961 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association on how much to say to patients diagnosed with cancer [1]. In Oken's study, the inspiration for subsequent studies on truth-telling, the majority of physicians (88%) agreed not to inform a cancer patient of his or her diagnosis. Eighteen years later, Novack and others replicated Oken's study and found a radical change in professed beliefs: 98% of physicians said that their general policy was to tell patients their diagnosis [2]. This divergence underscored how physicians' personal policies had transformed over time, going from a “practically never inform” policy in 1961 to a “nearly always inform” policy in 1979. In the brief course of two decades, there was a sea change in how doctors broke bad news.

This change has been attributed to the social transformation of the 1960s and 1970s, decades in which a broad questioning of hierarchies and the U.S. civil rights movement fostered a greater concern for patient self-determination and, with it, the notion of a patient's need to know his or her diagnosis so as to make informed choices. These evolving norms coalesced in legal standards for disclosure [3], a trend fostered by an enhanced ability to detect and treat many forms of cancer [4].

Despite a radical change in practice in the U.S., this trend has been neither universal nor temporally concordant across the globe, reflecting differing cultural norms. A cross-European study concluded, in 1993, that doctors from northern Europe disclosed diagnoses to patients and families almost without exception, whereas southern and eastern European doctors preferred not to disclose any information [5]. Researchers in Norway showed that the great majority of physicians fully informed their cancer patients of their diagnosis [6]. Scholars such as the Spanish bioethicist and medical historian Diego Gracia Guillen have traced such differences to the extent of the northward expansion of the Roman Empire and the subsequent divide between the communitarianism of southern Europe and the individualism of northern Europe [7]. An example of this variance is seen in Gracia's native Spain, where only 30% of physicians informed cancer patients of their diagnosis according to a study by Rodríguez-Marín and others published in 1996 [8]. Cases of intentional nondisclosure—indeed of ingenious schemes to deceive patients—have been reported from Spain [9], indicating, at the very least, the incomplete penetration of North American norms relating to truth-telling.

Disclosure in the Arab World

There is rather limited information on physicians' attitudes toward informing patients of cancer diagnoses in the Arabic-speaking and Muslim world, although there seems to be a mismatch between what patients prefer and what doctors and families actually do. Al-Amri showed, in 2009, that an overwhelming majority of Saudi nationals wanted to be fully informed of their cancer diagnosis [10], whereas Younge et al. [11] reported that consent for cancer treatment is usually given by a family member, rather than by the patient, and that families and doctors agree that this approach avoids upsetting the patient.

Studies consistently highlight that sociocultural elements in the Arab and Muslim world play a role in determining how much—or how little—information should be shared with a patient diagnosed with cancer. A study on cancer and truth-telling in Lebanon showed that 47% of physicians disclosed the truth to cancer patients whereas 53% did not [12]. An editorial article from Iran asserted that there were positive benefits, such as the prevention of psychological harm, when a terminal diagnosis is withheld from the patient [13].

Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to assess physicians' policies and practices toward informing patients of their cancer diagnosis. We also aimed at exploring whether or not physicians' disclosure policies and practices are associated with their sociodemographic, religious, cultural, and educational backgrounds.

Methods

The study was cross-sectional in nature, whereby a convenience sample of 131 physicians from nine different Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) hospitals and outpatient centers were given the study instrument to complete. HMC is the de facto national health service of Qatar. It provides a comprehensive spectrum of health care services to 100% of Qatar's 1.7 million national and foreign residents. The corporation consists of a conglomerate of seven hospitals and 22 satellite outpatient centers, staffed by 2,685 physicians representing 46 medical and surgical specialties and subspecialties [14].

Physicians were contacted during departmental meetings or individually in their offices. Although all physicians in the sample could theoretically have cancer patients in their practices, only 13% were oncologists. The time period for data collection was May to June 2011.

The study instrument was developed using the basic structure of Oken [1] and later Novack et al. [2]. In addition to the information collected by those studies, our study added questions to capture cultural and religious factors that might be associated with a respondent's attitudes and practices. The instrument can be found in supplemental online data.

An earlier version of the questionnaire was piloted for clarity and relevance on 10 doctors with faculty appointments at the Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar (WCMC-Q). Several edits were made. Data from the pilot test were not used for this analysis. There was no need to translate the instrument to Arabic because all physicians were fluent in English, which is the working language of medicine in Qatar. The study was confidential, voluntary, and anonymous. It was self-administered. The institutional review boards of WCMC-Q and HMC approved the study.

Statistical Analysis

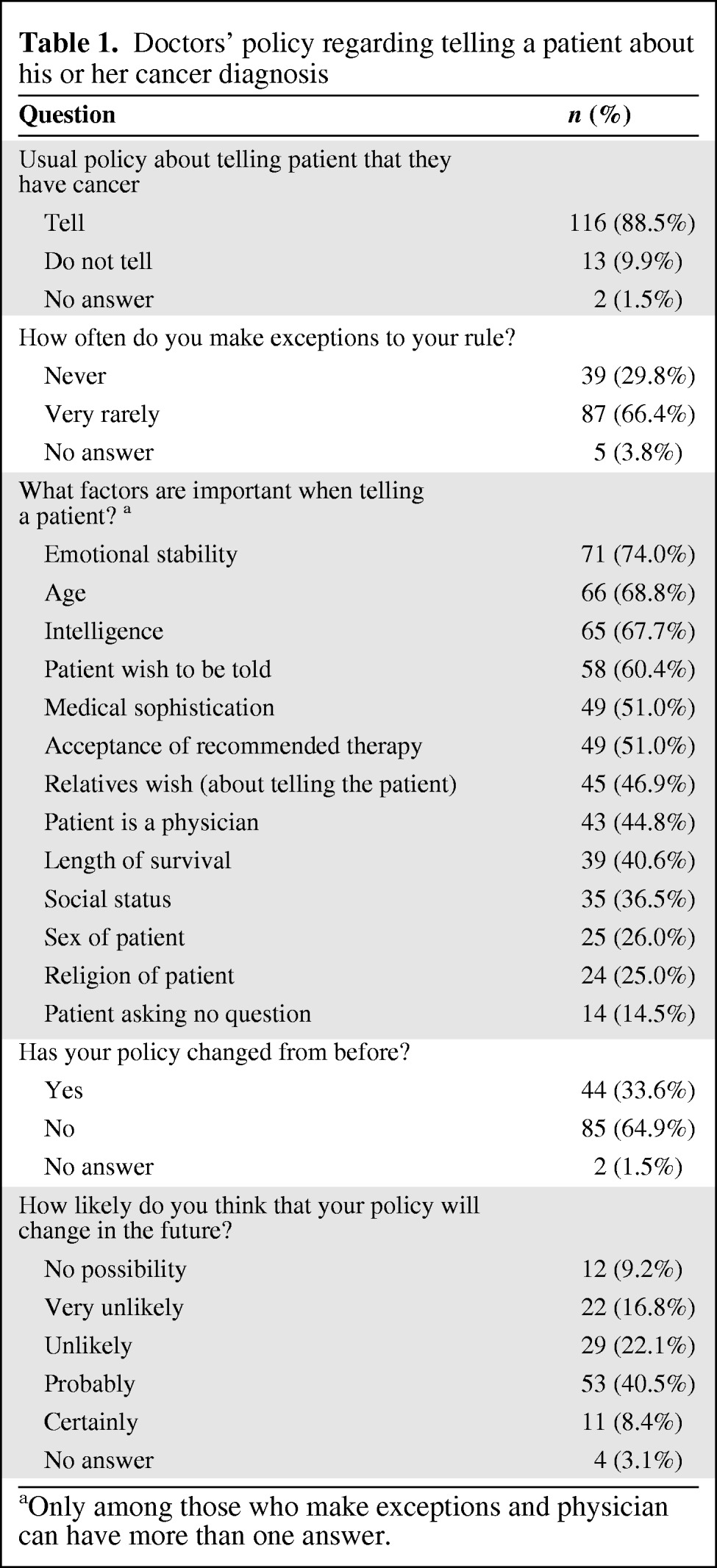

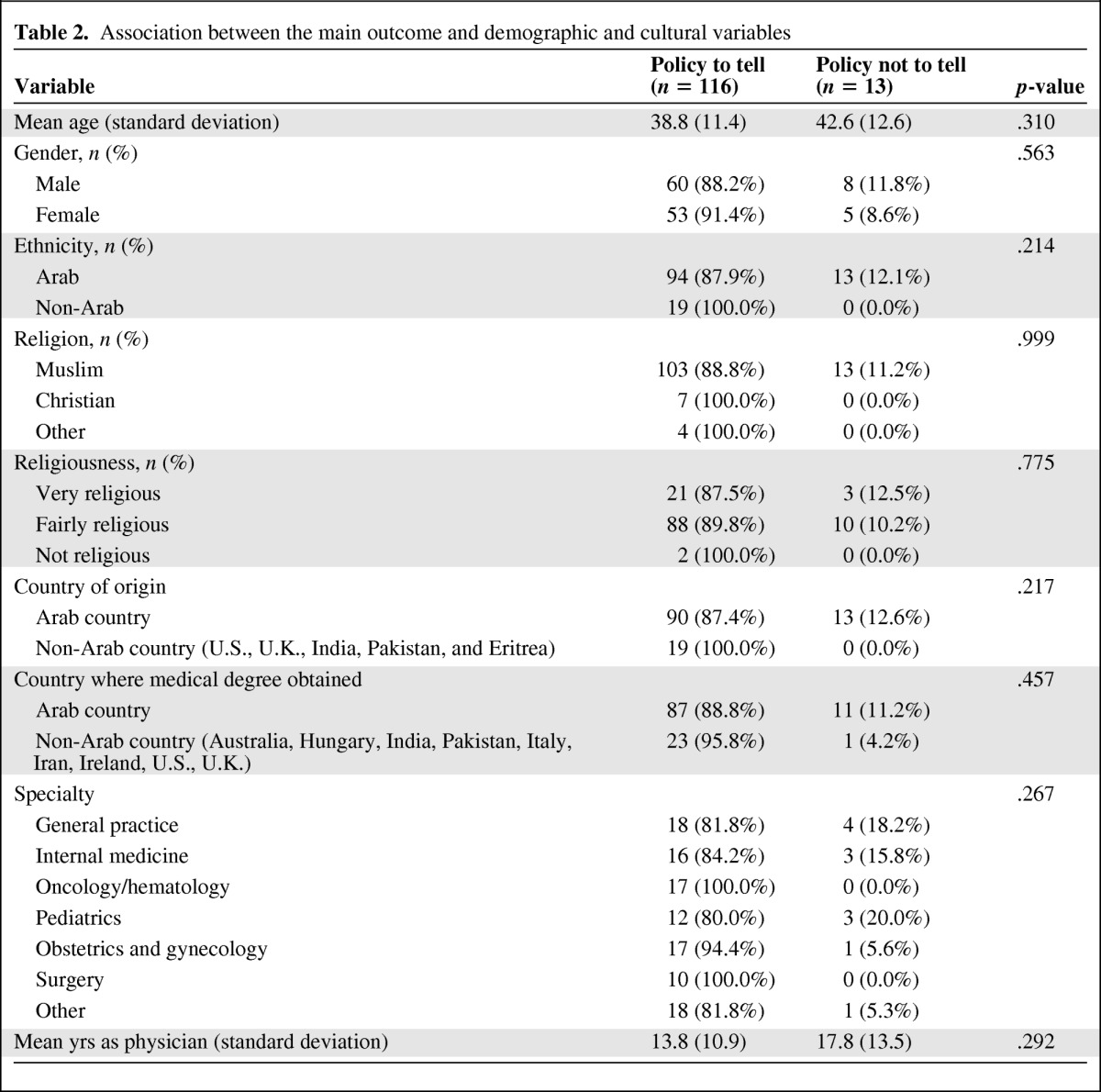

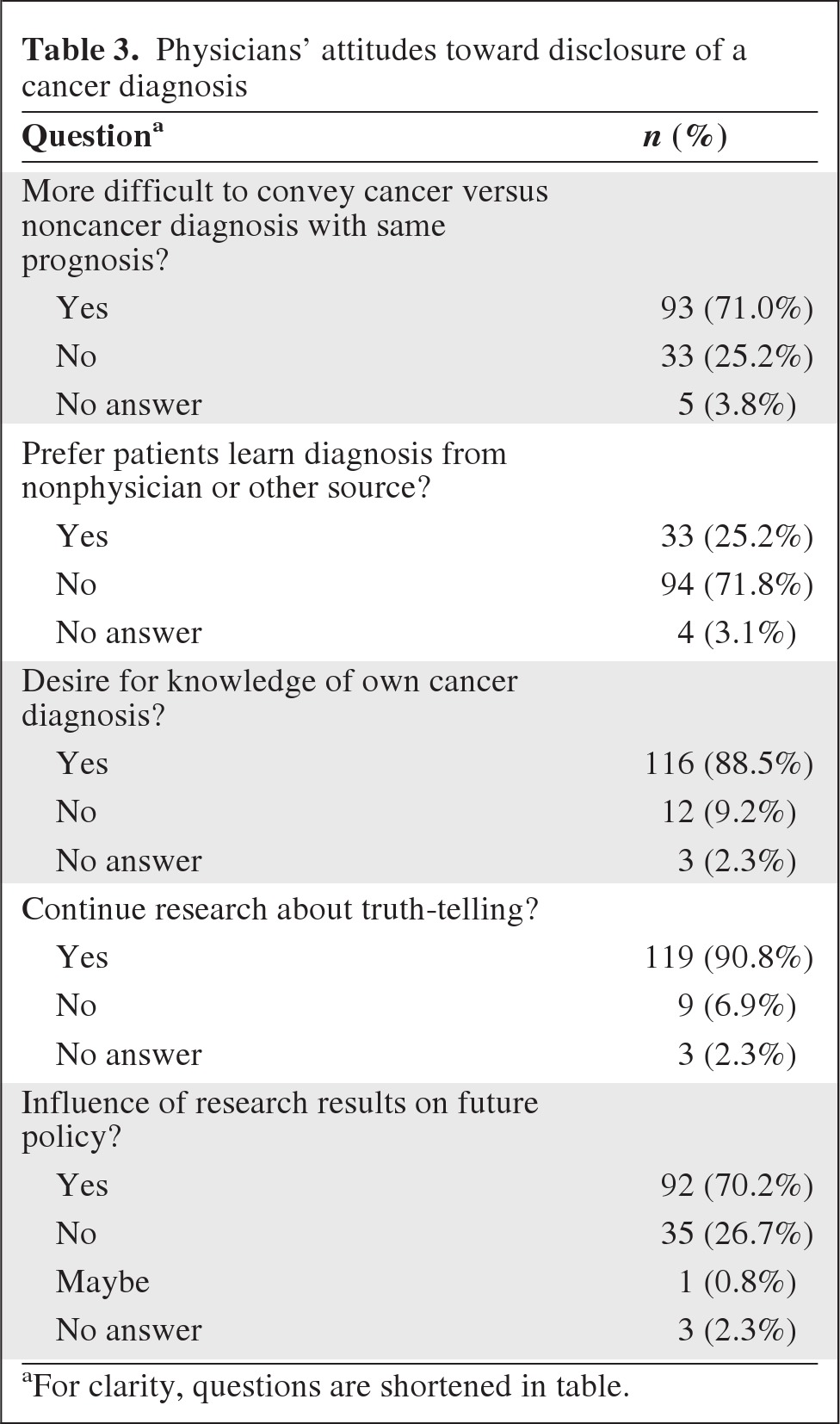

Sample characteristics were summarized using means and standard deviations for numerical variables such as age and frequency distributions for categorical variables such as policy and gender. The prevalence of physicians who usually tell their patients about their cancer diagnosis was computed along with its 95% confidence interval (CI). Moreover, we computed the prevalence and 95% CI of those who, in rare cases, make exceptions to their stated policy and tested whether or not making exceptions was different between those who usually tell and those who do not tell using Fisher's exact test. Rationales for making exceptions were summarized using frequency distributions (Table 1). Associations between doctors' policies and demographic, religious, cultural, and educational variables were evaluated using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for numeric variables (Table 2). Doctors' attitudes toward truth-telling to patients and future research in the field were summarized using frequency distributions (Table 3). All analyses were done using IBM SPSS, version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Significance was set at the 0.05 level.

Table 1.

Doctors' policy regarding telling a patient about his or her cancer diagnosis

aOnly among those who make exceptions and physician can have more than one answer.

Table 2.

Association between the main outcome and demographic and cultural variables

Table 3.

Physicians' attitudes toward disclosure of a cancer diagnosis

aFor clarity, questions are shortened in table.

Results

All 131 physicians surveyed agreed to participate, for a 100% participation rate. The average age of participants was 39.3 ± 11.5 years (range, 23–68 years). The majority were male (54.7%). The vast majority were Arabs (85.2%) and Muslims (90.7%). Most of the physicians considered themselves “fairly religious” (78.6%), whereas 19% considered themselves “very religious” and 2.4% considered themselves “not religious.”

Regarding specialty, 13.0% were oncologists or hematologists, 14.5% were internists, 16.8% were general practitioners, 11.5% were pediatricians, 13.7% were obstetrician–gynecologists, 7.6% were surgeons, 15.3% had another specialty, and 7.6% had an undeclared specialty. Nearly one in five participants (19.5%) received their medical training in a non-Arab country. Most of the doctors in this study (61.3%) had practiced in Qatar for the majority of their career.

With regard to the central question of truth-telling, a large majority of respondents (88.5%; 95% CI, 81.8%–93.4%) reported that their usual policy was to tell patients of their cancer diagnosis but, notably, a majority also revealed that they would make exceptions in rare cases (66.4%; 95% CI, 57.6%–74.4%). The percentage of physicians who would make exceptions to their policy was significantly higher among physicians whose usual policy was to tell (74.3%) than among those whose usual policy was not to tell (23.1%). Moreover, there was fluidity in their views. A third of respondents said that their policy had changed over the years and about half thought that their policy would probably or certainly change in the future, although they did not specify whether the direction would be more forthcoming or not.

The most frequently reported factors that physicians would take into account when making an exception to truth-telling were the patient's emotional stability (74.0%), age (68.8%), and perceived intelligence (67.7%). To a lesser extent, the patient's sex (26%) and religion (25%) were still considered when making an exception to the truth-telling practice.

In this rather homogeneous sample, there were no clear associations between the propensity to disclose and sociodemographic or cultural or religious variables (Table 2). Nevertheless, some trends were observed. For example, we noticed that only Arab and Muslim doctors, or doctors who had studied in the region, reported that their usual policy was to not tell. Moreover, although not statistically significant, physicians who reported that their usual policy was to tell patients about their cancer diagnosis were, on average, 5 years younger than their nondisclosing counterparts.

As shown in Table 3, a majority (71.0%) of participants responded with “yes” to the question of whether or not it is more difficult to inform a cancer patient of his or her diagnosis than a patient who has another disease with the same prognosis. One in four physicians reported that they would prefer that patients learn of their diagnosis from “other people.”

When asked whether or not they would like to be informed of their diagnosis if they were the patient, most doctors (88.5%) responded that they would want to know the truth.

The vast majority of physicians (90.8%) felt that more research should be carried out in this area of biomedical ethics to guide practice. The majority responded that their policy might change (70.2%) based on the results of empirical research.

Limitations

Because this is a cross-sectional study, no direction of the association found can be claimed definite. The sample was convenient in nature, yet diverse in terms of demographics and representative in terms of ethnicity. The size of the sample might have limited our ability to assert the observed trends with statistical significance. However, this is the first study of its kind in Qatar, and possibly the Gulf region, and although more research is needed in this area, the results address the main research questions. The study also establishes baseline values for current practices in Qatar, which could allow for future longitudinal studies of truth-telling and disclosure.

Discussion

It is clear from the study that most doctors in Qatar support truth-telling when there is a cancer diagnosis; their practices are all statistically similar and the majority declare a policy of full disclosure. However, this policy seems to be elastic and contingent upon circumstances. We note that 74.3% of respondents stated that they would make exceptions to their general norm of disclosure, although they asserted that this would only happen in very rare situations, a situation which itself is ill-defined and open to interpretation. This suggests that the stated views may not equate with actual practice, a point substantiated by the fact that ∼50% of doctors responded that their stance on truth-telling was likely to change or might certainly change in the future.

Our study suggests that, even though most doctors believe as a matter of principle that patients should be informed, in reality they make room for exceptions. These exceptions, which could undermine the principle, warrant further study and need to be understood in a cultural context. This is especially salient because of physicians' willingness to change policy depending upon circumstance. This speaks to the frailty of the norm.

Disclosure policy is, thus, still a shifting issue for most doctors. This may be why there are generally no fixed institutional policies about truth-telling and why doctors seem open to embracing new norms.

Nevertheless, we found it notable that, despite the above-mentioned uncertainties—or perhaps because of them—most doctors believe that patients should learn about their diagnosis from a physician and not from someone else. This indicates to us that doctors in Qatar accept this professional responsibility and appreciate that there may be adverse consequences when disclosure is left in the hands of nonphysicians. It may also call attention to the fact that physicians in Qatar underestimate the role of allied professions—psychology and social work—in patient care, a topic worthy of further exploration.

Exceptions to truth-telling to patients were less prompted by the patient's gender (26%), religion (25%), and social status (36.5%) than by his or her emotional stability (74%), age (68.8%), and intelligence (67.7%). In addition, about half of the physicians who made exceptions took into consideration the wishes and preferences of relatives, which may be a result of the nature of familial ties in the Arab region. In other words, the context of care seems to come into play. Doctors define a particular policy for each case, depending on contextual information. This pattern is consistent with what two of us (P.R.P. and J.J.F.) have discussed elsewhere, in the sense that in so-called high-context cultures, such as those of the Mediterranean basin and the Arabic-speaking countries, individuals are highly sensitive to contextual clues [15, 16].

Although there were no associations between the physicians' policy and their sociodemographic and cultural backgrounds, we noted that 100% of non-Arab and non-Muslim doctors had a policy of always telling patients of their cancer diagnosis, whereas >11% of Arab and Muslim doctors were categorical about a nondisclosure policy. Conversely, most physicians who attended medical school in non-Arab countries—except for one outlier—favored full disclosure. More data are needed to confirm this putative correlation between education and beliefs. Although our sample size did not reach statistical significance, our findings could indicate that cultural background and education play a role in shaping disclosure policies. More research is needed to fully understand a possible correlation.

The data suggest that relative youth correlates with a more forthcoming attitude toward disclosure. This may reflect a generational shift in practice or perhaps be covariant with the greater likelihood that young physicians were trained abroad.

Yet, irrespective of their background and professed beliefs, a high percentage of physicians would make exceptions to their generally stated disclosure norm. That 74.3% of physicians reported resorting to what in the West is described as the “therapeutic privilege,” that is, taking the prerogative of nondisclosure, shows the fragility of the norm in this context. We do not have data on the percentage of cases for which the therapeutic privilege was actually invoked or on the specific circumstances. This could be the object of a prospective analysis.

Conclusions

Despite all the progress in cancer therapy and its increasingly favorable prognosis in many cases, informing patients about their diagnosis of cancer is still vexing for many doctors. But no matter how challenging, doctors in Qatar report that informing patients of this diagnosis is their responsibility and one they are willing to assume.

Our study provides insight into this process in Qatar and reveals that doctors, more or less independently of their nationality, religion, or place of study, are in principle all equally inclined to inform patients about their diagnosis of cancer. But importantly, we also found that physicians are ready to adjust their policies by making exceptions on a case-by-case, patient-by-patient basis.

Notably, the majority of doctors seem to feel that their policy on informing patients of their diagnosis of cancer could change in the future, depending on what research shows. This is a welcome development and shows the openness of the Qatari medical community to empirical evidence and the evolving knowledge of practice norms.

Knowledge from empirical studies in bioethics can inform strategies aimed at enhancing doctor–patient communication in Qatar, an essential step in furthering patient rights in a culturally sensitive fashion and in providing better care for patients from this region in an increasingly globalized world.

See www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by grant UREP 08-131-3-026 from the Qatar National Research Fund under its Undergraduate Research Experience Program. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Qatar National Research Fund. Dr. Fins gratefully acknowledges the support of Clinical and Translational Science Center (UL1)-Cooperative Agreement (CTSC) 1UL1 RR024996 to Weill Cornell Medical College (New York).

Footnotes

- (C/A)

- Consulting/advisory relationship

- (RF)

- Research funding

- (E)

- Employment

- (H)

- Honoraria received

- (OI)

- Ownership interests

- (IP)

- Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder

- (SAB)

- Scientific advisory board

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Pablo Rodriguez del Pozo, Joseph J. Fins, Ziyad Mahfoud

Provision of study material or patients: Ismail Helmy

Collection and/or assembly of data: Pablo Rodriguez del Pozo, Rim El Chaki, Tarek El Shazly, Deena Wafadari, Ziyad Mahfoud

Data analysis and interpretation: Pablo Rodriguez del Pozo, Joseph J. Fins, Ismail Helmy, Rim El Chaki, Tarek El Shazly, Deena Wafadari, Ziyad Mahfoud

Manuscript writing: Pablo Rodriguez del Pozo, Joseph J. Fins, Ismail Helmy, Rim El Chaki, Tarek El Shazly, Deena Wafadari, Ziyad Mahfoud

Final approval of manuscript: Pablo Rodriguez del Pozo, Joseph J. Fins, Ismail Helmy, Rim El Chaki, Tarek El Shazly, Deena Wafadari, Ziyad Mahfoud

References

- 1.Oken D. What to tell cancer patients. A study of medical attitudes. JAMA. 1961;175:1120–1128. doi: 10.1001/jama.1961.03040130004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novack DH, Plumer R, Smith RL, et al. Changes in physicians' attitudes toward telling the cancer patient. JAMA. 1979;241:897–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faden R, Beauchamp T. A History and Theory of Informed Consent. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. pp. 1–392. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arruebo M, Vilaboa N, Sáez-Gutierrez B, et al. Assessment of the evolution of cancer treatment therapies. Cancers. 2011;3:3279–3330. doi: 10.3390/cancers3033279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomsen OO, Wulff HR, Martin A, et al. What do gastroenterologists in Europe tell cancer patients? Lancet. 1993;341:473–476. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loge JH, Kaasa S, Ekeberg O, et al. Attitudes toward informing the cancer patient—a survey of Norwegian physicians. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1344–1348. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gracia D. Spanish bioethics comes into maturity: Personal reflections. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2009;18:219–227. doi: 10.1017/S0963180109090367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez-Marin J, Lopez-Roig S, Pastor MA. Doctors' decision-making on giving information to cancer patients. Psychol Health. 1996;11:839–844. doi: 10.1080/08870449608400279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fins JJ. Bruera E, Portenoy RK. Topics in Palliative Care. Volume 5. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. Truth telling and reciprocity in the doctor-patient relationship: A North American perspective; pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Amri AM. Cancer patients' desire for information: A study in a teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Younge D, Moreau P, Ezzat A, Gray A. Communicating with cancer patients in Saudi Arabia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;809:309–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamadeh GN, Adib SM. Changes in attitudes regarding cancer disclosure among medical students at the American University of Beirut. J Med Ethics. 2001;27:354. doi: 10.1136/jme.27.5.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghavamzadeh A, Bahar B. Communication with the cancer patient in Iran. Information and truth Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;809:261–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamad Medical Corporation. Annual Health Report 2010. Doha, Qatar: HMC; 2011. Jul, Department of Epidemiology and Medical Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodríguez del Pozo P, Fins JJ. Islam and informed consent: Notes from Doha. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2008;17:273–279. doi: 10.1017/S096318010808033X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fins JJ, Rodríguez del Pozo P. The hidden and implicit curricula in cultural context: New insights from Doha and New York. Acad Med. 2011;86:321–325. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318208761d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.