Abstract

Compounds that block estrogen action through the estrogen receptor (ER) or downregulate ER levels are useful for the treatment of breast cancer and endocrine disorders. In our search for structurally novel estrogens having three-dimensional core scaffolds, we found some compounds with a 7-oxabicyclo-[2.2.1]heptene core that bound well to the ERs. The best of these compounds, a phenyl sulfonate ester (termed OBHS for oxabicycloheptene sulfonate), was a partial antagonist on both ERα and ERβ. Although OBHS bears no structural resemblance to other estrogen antagonists, it appears to achieve its partial antagonist character by stabilizing a novel conformation of the ER that involves a significant distortion of helix-11. To enhance the antagonist properties of these oxabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane core ligands, we expanded the functional diversity of OBHS by replacing the sulfonate with secondary or tertiary sulfonamides (–SO2NR–), isoelectronic and potentially isostructural molecular replacements. An array of 16 OBHS sulfonamide analogues were prepared through a Diels–Alder reaction of a 3,4-diarylfuran using various N-aryl vinyl sulfonamide dienophiles. While the more polar secondary sulphonamides were weak ligands, certain of the tertiary sulfonamides had very good ER binding affinity. In HepG2 cell reporter gene assays, the sulphonamides had moderate potency, but they showed lower intrinsic transcriptional activity on ERα than the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) hydroxytamoxifen or OBHS, and they were inverse agonists on ERβ. Thus, the behaviour of these OBH-sulfonamides more closely mirrors the activity of full antagonists like the drug fulvestrant (ICI 182 780), and their greater antagonist biocharacter appears to arise from an accentuated distortion of helix-11.

Introduction

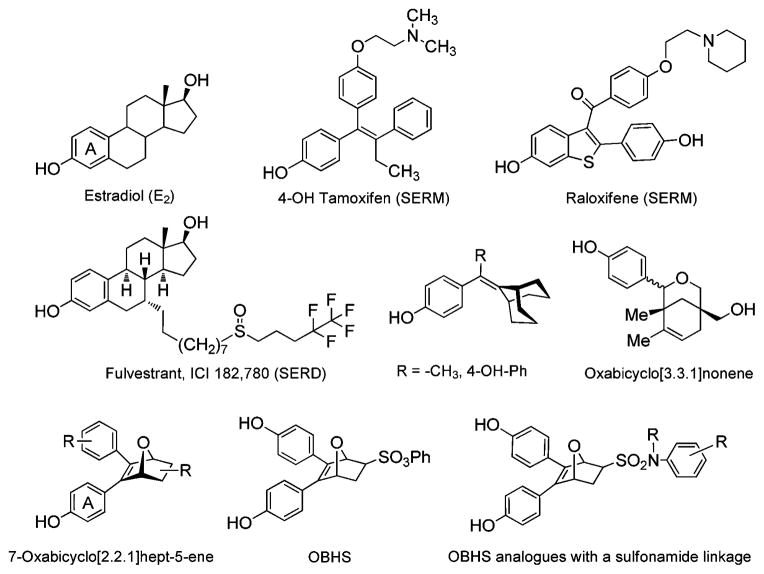

The estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ, regulate a diverse set of physiological and pathological processes and are well established pharmaceutical targets.1,2 In contrast to the pan-agonist activity of 17β-estradiol (E2, Fig. 1), Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) display agonist activity in certain tissues but antagonist activity in others,3,4 and some SERMs, such as tamoxifen and raloxifene, are used for the treatment of breast cancer or for menopausal hormone replacement.5–7 Because activity profiles of these SERM are not ideal and resistance to their effectiveness as antitumor agents can develop with time, there has been interest in finding new SERMs that might prove more effective as hormonal or therapeutic agents.6,7 ER ligands that reduce the level (as well as the activity) of ER are termed Selective Estrogen Receptor Downregulators (SERDs),8,9 and because they actually lower ER levels, SERDs are distinct from SERMs. SERDs such as fulvestrant (Fig. 1, ICI 182 780) are showing promise in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer, because they can inhibit the growth of tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells.10 Fulvestrant, however, has a poor oral bioavailability; so, there is also a need for improved SERDs.

Fig. 1.

The structure of estradiol, 4-OH tamoxifen, fulvestrant (ICI 182 780) and representative three-dimensional ER ligands, OBHS and title compounds.

In a new approach to develop novel SERMs and SERDs, we prepared compounds having a more three-dimensional central hydrophobic core topology than is typically found in steroidal and non-steroidal ER ligands. This design was inspired by structural studies of ligand complexes with ER that reveal ample unoccupied space above and below the mean plane of E2, particularly near the middle of this molecule.11,12 A number of structural motifs, such as the bridged bicyclo[3.3.1]nonene core systems (Fig. 1), have been explored by us13 and others14,15 to probe this extra space and exploit the flexibility of the ligand-binding pocket (LBP).

Recently, we evaluated three-dimensional ER ligands based on a different bridged oxabicyclo[2.2.1]heptene core (Fig. 1).16 The best compound, exo-5,6-bis-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonic acid phenyl ester (OBHS), exhibited relative binding affinity (RBA) values of 9.3% and 1.7% for ERα and ERβ, respectively (RBA[estradiol] = 100%). OBHS also profiled as a partial antagonist on both ER subtypes, even though it was structurally unlike typical ER antagonists. Through our recent structural studies of this compound17 as well as other members of this series,18 it became evident that the high ER binding affinity of OBHS relies on its two 4-hydroxyphenyl substituents, one which mimics the A-ring of estradiol, the other which projects into a subpocket that lies in the 11β direction with respect to estradiol in the complex with ERα. Of greater interest, however, was the fact that the large phenyl sulfonate moiety, which is too long and extended to fit into the ligand-binding pocket found in crystal structures of typical steroidal and non-steroidal estrogens and SERMs, was readily accommodated by a reorganization of the peptide backbone and residues at the end of helix-11. These changes provided sufficient volume to accommodate this large and extended group, without encountering a marked penalty in ligand binding affinity. This distortion of helix-11 was presumed to result in the overall partial antagonist character of OBHS-type ligands by an indirect—rather than a direct—mechanism through which helix-12 becomes displaced from its agonist conformation because of the dislocation of the C-terminus of helix-11, rather than by direct ligand contact with helix-12.19

We were intrigued by the role that the phenyl sulfonate moiety played in engendering the partial antagonist activity of OBHS ligands,17 and because of our interest in finding ER ligands that have more complete antagonist, even SERD activity, we have, in this study, queried the structure of OBHS at this very position by substituting the sulfonate with secondary and tertiary sulfonamide (–SO2NR–) linkages, keeping the remainder of the 7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene skeleton intact. While the secondary phenyl sulphonamides are isostructural to the phenyl sulfonate, the tertiary sulphonamides introduce an additional substituent that, as will be seen, is of consequence. We prepared a set of 16 OBHS sulfonamides (11a–q) by an efficient Diels–Alder approach,16 and we evaluated them for ER binding affinity, for transcriptional activity in a relevant cell culture assay system, and by computational modelling for structural analysis. In the process, we have identified some oxabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane sulphonamides that are more complete antagonists than even hydroxytamoxifen, having biological character more like that of fulvestrant (ICI 182 780). Computational modelling indicates that this more complete antagonist biocharacter arises from a more accentuated distortion of helix-11 by the sulphonamides than was effected by the phenylsulfonate of OBHS.

Results

Synthesis

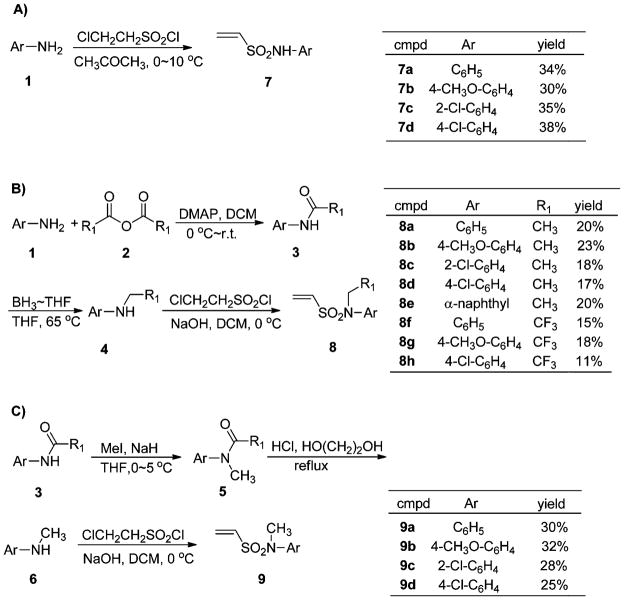

The target sulfonamides were prepared by Diels–Alder cycloaddition16 of 3,4-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)furan 10 with various sulfonamide dienophiles (7a–d, 8a–h and 9a–d, see ESI† for details),20,21 readily obtained from anilines (Scheme 1). Dienophiles with a secondary sulfonamide –SO2NH– system (7a–d) were prepared in a single-step by the reaction of 2-chloroethanesulfonyl chloride (1.2 equiv.) with the aniline 1 (Scheme 1A);22 tertiary sulfonamides (N-substituents CH3, CH2CH3, CH2CF3) were synthesized as shown (Scheme 1B and C). Acylation of anilines 1 with acetic anhydride or trifluoroacetic anhydride gave compounds 3a–h,23,24 and compounds 4 were obtained by borane reduction of compounds 3, under optimized conditions.25–27 The compounds 6 were prepared from 3 in two steps.28 In the first step, amide 3 was methylated by methyl iodide in the presence of sodium hydride in THF to afford 5. In the second step, deacylation of 5 in 10% HCl (0.25 mL for 1 mmol amide) and glycol (0.75 mL for 1 mmol amide) with refluxing for 24 h gave the compounds 6. Reaction of compounds 1, 4 and 6 with 2-chloroethanesulfonyl chloride gave dienophiles 7–9.

Scheme 1.

The synthesis of various dienophiles 7–9. (Yields given are for the final sulfonation step; yields for the other steps are given in the ESI†.)

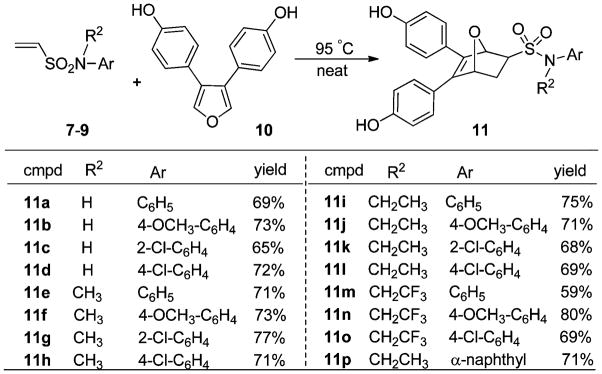

As was the case with the sulfonamides, the Diels–Alder cycloaddition with furan 10 proceeded well at 95 °C without solvent or catalysts, giving isolated yields of 60–80% (Scheme 2).16 As noted in the earlier sulfonate series, the products are almost exclusively exo diastereomers (see ESI† for 1H NMR assignments of exo 11p); apparently, the high rate and ready reversibility of this reaction results in the predominant formation of the product of thermodynamic control. All of the products are racemates.16

Scheme 2.

Diels–Alder reaction of 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl 10 with dienophiles 7–9.

Binding affinities

ER binding affinities, determined radiometrically,29 are expressed as relative binding affinity (RBA) values, with estradiol = 100 (Table 1). The ER binding affinities depend on the nature of substituents on both the sulfonamide nitrogen and phenyl group. The RBA values of the secondary sulfonamide – SO2NH– compounds (11a–d) are all rather low (entries 1–4), but all of the tertiary sulfonamides (11e–o) bound much better. The N-methyl compounds 11e–h, in particular, showed moderate to high binding affinities (entries 5–8), with compound 11g being best (7.17% and 1.59% for ERα and ERβ, respectively). Affinity decreased with increasing alkyl chain length, however, with the trifluoroethyl compounds (11m–o) having binding affinities similar to or somewhat lower than those of the ethyl compounds (11i–l).

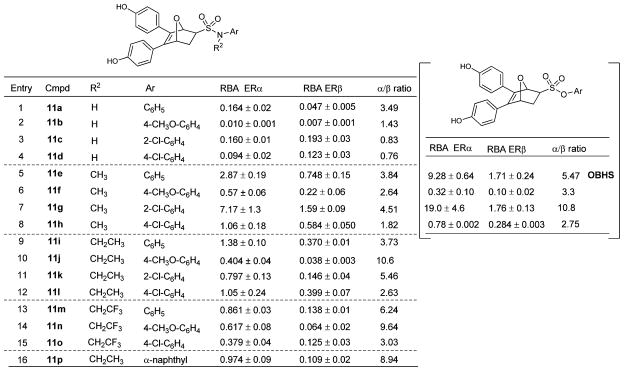

Table 1.

Relative binding affinities (RBAs) of the compounds 11a–p for ERα and ERβa

|

Relative binding affinity (RBA) values, determined by radiometric assays, are expressed as IC50 estradiol/IC50 compound × 100 ± the range or standard deviation (RBA, estradiol = 100%). The Kd for estradiol is 0.2 nM (ERα) and 0.5 nM (ERβ).

Substituents on the pendant phenyl group of the tertiary sulfonamides also affected binding affinity and selectivity, with most ligands showing moderate to good binding affinity; those with no substitution (11a, 11e, 11i and 11m) were overall the best, with the exception of the ortho-chloro phenyl analogue 11g. The para chloro and methoxyl phenyl analogues usually gave lower binding affinities; nevertheless, the sulfonamide with the bulkiest substituent (α-naphthyl) still bound well. The tertiary sulfonamides showed 2.5–11-fold affinity preferences for ERα. It is notable that the affinities of the N-methyl sulfonamides (11e–h) were comparable with those of the corresponding sulfonates, on which we have recently reported (Table 1, right, data in square brackets),17 the best sulfonamide (11g) being comparable to the original OBHS compound, 7.2% and 1.6% (11g) vs. 9.3% and 1.7% (OBHS), for ERα and ERβ, respectively.16

Transcriptional activity

While SERMs generally profile as antagonists in breast cancer cells, they display considerable gene activation in other cell lines that correlates more accurately with their uterotrophic activity in vivo.30 For this reason, we profiled these compounds in human hepatocarcinoma (HepG2) cells, using expression plasmids for full-length human ERα or ERβ and an estrogen-responsive luciferase reporter gene.31 Compounds were assayed alone for direct activation (agonism) and in the presence of 10 nM E2 for antagonism. Since none of the compounds activated ERβ, we report only ERβ antagonist data. Agonist and antagonist potencies are given as EC50 and IC50 values, respectively. The intrinsic activity, noted as the % efficacy (%Eff) compared to 100 nM E2, is given in all cases. (Note, when efficacy is low, it is difficult to determine EC50 values for agonists, and when efficacy is high, it is difficult to determine IC50 values for antagonists.)

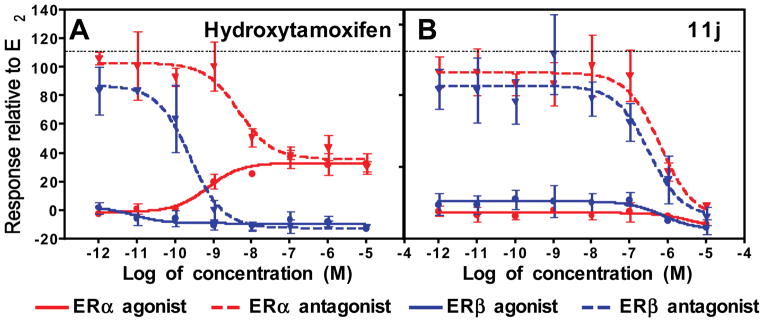

In these cells, the SERD, fulvestrant (ICI 182 780), acts as a full antagonist on both receptors (Table 2), while 4-OH tamoxifen (an active tamoxifen metabolite) displays the expected ERα-selective partial-activation profile (Table 2, Fig. 2A). While OBHS is a full antagonist in HEC-1 cells,16 in HepG2 cells it profiles with greater agonist efficacy than 4-OH tamoxifen. Because ERα and especially ERβ have considerable basal activity in HepG2 cells, compounds can show inverse agonist activity; those with intrinsic activity less than that of the apo-ER are reported with negative efficacy values.

Table 2.

Effects of compounds 11a–p on ER-mediated transcription

| Compounde | Agonist modea

|

Antagonist modeb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERα

|

ERα

|

ERβ

|

||||

| EC50 (μM) | Eff (%E2) | IC50 (μM) | Eff (%E2) c | IC50 (μM) | Eff (%E2) c | |

| 11a | 0.10 | 78 ± 1 | — | 83 ± 5 | 0.37 | 21 ± 6 |

| 11c | 0.20 | 81 ± 4 | — | 89 ± 4 | 0.10 | −5 ± 3 |

| 11d | — | 42 ± 3 | — | 65 ± 3 | 0.10 | −15 ± 1 |

| 11e | — | 31 ± 3 | 0.74 | 56 ± 2 | 0.01 | −25 ± 3 |

| 11g | 0.008 | 33 ± 1 | 0.45 | 41 ± 1 | 0.12 | −24 ± 3 |

| 11i | — | 11 ± 1 | 0.35 | 10 ± 2 | 0.33 | −10 ± 2 |

| 11j | — | 3 ± 1 | 0.72 | 3 ± 1 | 0.37 | −4 ± 4 |

| 11k | — | 13 ± 1 | 0.75 | 20 ± 4 | — | 3 ± 3 |

| 11l | — | 1 ± 1 | 0.43 | 7 ± 1 | 0.16 | −12 ± 1 |

| 11m | — | 9 ± 2 | 0.19 | 3 ± 1 | 2.14 | 0 ± 2 |

| 11nd | — | 0 ± 0 | n.d. | −12 ± 0 | n.d. | 45 ± 5 |

| 11o | — | 3 ± 3 | 0.93 | 3 ± 2 | 4.08 | 7 ± 2 |

| 11p | 0.086 | 24 ± 0 | 6.49 | 23 ± 2 | 2.36 | 31 ± 2 |

| Fulvestrant | — | 1 ± 1 | 0.00033 | −7 ± 1 | 0.00058 | −23 ± 0 |

| 4-OH TAM | 0.0011 | 35 ± 3 | 0.0030 | 35 ± 3 | 0.00063 | −20 ± 2 |

| OBHS | 0.028 | 57 ± 3 | 0.014 | 70 ± 12 | 0.16 | −2 ± 5 |

Transcriptional activity in HepG2 cells transfected with 3X-ERE-driven luciferase reporter and ERα or ERβ expression vectors treated in triplicate with doses of the compounds (up to 10−5 M). Average efficacy (mean ± s.e.m.) is shown as a percentage of 10−7 M E2.

IC50 and average efficacy (mean ± s.e.m.) determined in the presence of 10−8 M E2 on ERα or ERβ.

ERs have considerable basal activity in HepG2 cells; compounds with inverse agonist activity are given negative efficacy values.

A single dose (10−5 M) of 11n was tested.

Compounds 11b, 11f, and 11h were not assayed.

Fig. 2.

Luciferase activity was measured in HepG2 cells transfected with 3X-ERE-driven luciferase reporter and expression vectors encoding ERα or ERβ, and treated in triplicate with increasing doses (up to 10−5 M) of A. Hydroxytamoxifen; B. Compound 11j. The average efficacy (mean ± s.e.m.) is shown as a percentage of 10−7 M 17β-estradiol (E2). For the antagonist mode the average efficacy (mean ± s.e.m.) of the compounds was determined in the presence of 10−8 M E2 and is shown as a percentage of 10−8 M E2.

With ERα there is a clear trend where agonist activity decreased with an increase in the N-alkyl chain length (11a > 11e > 11i). Overall, the N-ethyl and trifluoroethyl compounds have very low efficacy, with those having a 2-chlorophenyl substitution (11c, 11g, 11k) showing greater agonist activity than those with substitutions at the 4-position. Also, the naphthyl derivative (11p) induced nearly full agonist activity on ERα, despite the bulky N-ethyl sulfonamide substitution, highlighting that both substituents on nitrogen are important. Shown in Fig. 2B is a representative assay curve for a low-efficacy compound (11j), which has an intrinsic activity on both ERα and ERβ as low as that for fulvestrant (Table 2).

On ERβ, most of the compounds profiled as inverse agonists, similar to fulvestrant. The inability to fully displace E2 for a few compounds may reflect their low affinity, as they did not activate ERβ on their own.

Discussion

In this work, we have expanded the chemical diversity of OBHS-type ligands by substitution of the sulfonate moiety with a sulfonamide (–SO2NR–) linkage, a molecular replacement that is isoelectronic and potentially isostructural. A small array of 16 OBHS analogues (11a–p) were prepared in moderate to good yield, through a Diels–Alder reaction of a 3,4-diarylfuran with various dienophiles of N-aryl vinyl sulfonamides under neat, mild conditions, without catalysts.

The structure–activity relationships that emerge for these OBHS sulfonamide analogues from binding and cell-based activity assays reveal that the affinities depend on the nature of the substituents on both the nitrogen atom and the phenyl group of the sulfonamides; the highest affinity being observed in tertiary sulfonamides having small N-alkyl groups and binding enhancing groups on the phenyl group.

Even though the secondary sulphonamides are more isostructural to the sulfonates than are the tertiary sulphonamides, their lower affinity is not surprising. The N–H group in the secondary sulphonamides presents a hydrogen bond donor in a region of the receptor that has no available hydrogen bond acceptor. It is well known that introduction of strong hydrogen bonding groups, both donors and acceptors, in the “middle” of ER ligands generally results in significantly reduced binding affinities.32,33 The tertiary sulphonamides, however, have masked this hydrogen bond donor with an alkyl group, and some of these compounds demonstrated affinities and ERα selectivity comparable to those of the parent sulfonate systems, OBHS and its analogues.

The second substituent, which can be added in the sulphonamide—but not the sulfonate—system, not only improves binding affinity, but also leads to enhanced antagonist activity, giving compounds that are full antagonists of both ER subtypes, similar to the drug fulvestrant (ICI 182 780), by a novel mechanism.

Structural analysis of the origin of the enhanced antagonist character of OBH-sulfonamides

E2 supports transcriptional activation of ERs by stabilizing helix 12 in a conformation forming one side of a binding groove for transcriptional coactivator proteins (Fig. 3A), while its high affinity derives both from its relatively flat shape and hydrogen bonding on both ends of the ligand: helix-3/E353, R394 and helix 11/H524 in ERα.11 SERMs and full ER antagonists have typically been developed by starting with an agonist, and then adding a bulky side group that physically relocates helix-12 out of this position by direct displacement (Fig. 3B), thus blocking the recruitment of transcriptional coactivator proteins, such as histone acetyl transferases (HATs).12 The residual agonist activity seen with tamoxifen is due to an allosteric activation of a second coactivator-binding site on the ER N-terminus, termed AF-1, via an unknown mechanism.

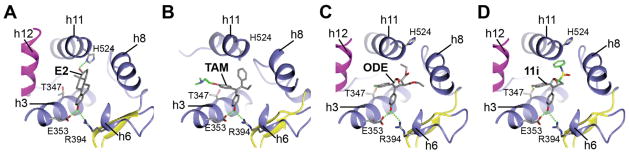

Fig. 3.

Modeling of ERα bound to oxabicyclic heptane sulphonamide (OBH-sulfonamide). ERα bound to A. E2 (pdb.1ERE); B. 4-Hydroxytamoxifen; C. ODE (pdb.2QH6),18 which has the same oxabicyclic core as the sulfonamides. D. Model of the sulfonamide 11i based on the ODE structure. The model was constructed by substitution of the ODE ester functions with the N-ethyl phenyl sulfonamide; the strong hydrogen bonding patterns of the phenols maintained the position of the ligand core. Accommodation of the aryl sulfonamide would require a shift in helix 11, predicted to disrupt the helix 11–helix 12 interface and block agonist activity by an indirect antagonism mechanism.19

Previously, we reported crystal structures of much smaller oxabicyclic core derivatives, such as the diethyl ester ODE (pdb.2QH618), as well as, more recently, that for OBHS itself.17 These structures revealed a novel mechanism of antagonism without the use of the bulky side chain traditionally found in SERMs: ligand-induced repositioning of helix-11 indirectly modulates helix-12 positioning and receptor activity, a process we had previously termed “passive antagonism”,19 but might more appropriately be called “indirect antagonism”.

The diaryl oxabicyclic core ligands achieve this indirect antagonism in a unique way: one of the phenols mimics the role of the A-ring phenol of E211 or one of the phenols in diethylstilbestrol,12 engaging in strong hydrogen bonds with E353 and R394 and a structured water in ERα. The second phenol of OBHS makes a distinct hydrogen bonding interaction involving helix-3/T347. This latter interaction is energetically favourable, because deletion of the second phenolic OH or its etherification greatly reduces ER binding affinity.16 While this second phenol points in the E2 11β direction, as do the third aryl groups in the SERMs, hydroxytamoxifen and raloxifene, it is not long enough to interact directly with helix-12 and displace it, as do these SERMs. Consequently, OBHS does not have a hydrogen bonding interaction to constrain helix 11 by interaction with H524 (Fig. 3C). The crystal structures show that the large, non-polar phenyl sulfonate group in OBHS,17 and to a lesser extent the ethyl carboxylate group in the smaller analogues,18 make strong steric clashes with helix-11, displacing H524 and repositioning helix-11 in a manner that indirectly modulates helix-12 positioning and reduces receptor agonist activity, which is the essence of indirect antagonism.19

Molecular modelling indicates that the aryl sulfonamide substituents could be accommodated in a manner similar to that of aryl sulfonate groups in the OBHS analogues (Fig. 3D). The additional bulk of the tertiary sulphonamides, however, would be expected to accentuate this clash with helix-11, which would result in a greater reduction in agonistic efficacy than that shown by the sulfonates. This is illustrated with the N-ethyl sulfonamide 11i, which is a low efficacy compound that is an analogue of both ODE and OBHS.

Thus, it appears that the enhanced indirect antagonism of the OBH-sulfonamides compared to the OBH-sulfonates, can account for their ability to achieve full antagonism, without the need for a bulky side chain that disrupts helix-12 directly. While it is possible that the scaffold flips to allow the sulfonamide to exit towards helix 12, this would require accommodation of the L-shaped configuration of the two phenols within the pocket, which up to now has never been seen with an ER ligand, as well as the loss of the key hydrogen bonding interaction with T347. Thus, the oxabicyclic heptane sulfonamides may represent a novel binding epitope to generate full antagonists on both ERα and ERβ.

Conclusion

Oxabicyclic heptane sulfonamides appear to represent a novel binding epitope that can generate full ERα and ERβ antagonists with intrinsic activity as low as that of fulvestrant (and possibly also SERD activity). This is an issue that we are exploring further.

Experimental section

Materials and methods

Unless otherwise noted, reagents and materials were obtained from commercial suppliers and were used without further purification. Tetrahydrofuran and toluene were dried over Na and distilled prior to use. Dichloromethane was dried over CaH2 and distilled prior to use. Glassware was oven-dried, assembled while hot, and cooled under an inert atmosphere. Unless otherwise noted, all reactions were conducted in an inert atmosphere. Reaction progress was monitored using analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Visualization was achieved by UV light (254 nm). 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were obtain on Bruker Biospin AV400 (400 MHz) instrument. The chemical shifts are reported in ppm and are referenced to either tetramethylsilane or the solvent. Mass spectra were recorded under electron impact conditions at 70 eV. Melting points were obtained on SGW X-4 melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. Flash chromatography was performed with silica gel (0.040–0.063 mm) packing.

General procedure for the synthesis of dienophiles 7–9

The synthesis of dienophiles 7. 2-Chloroethanesulfonyl chloride (1.2 equiv.) was added slowly to a solution of aniline (0.5 equiv.) in acetone at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred overnight at 0–10 °C, then evaporated in vacuo. The residue was dissolved into a mixture of CH2Cl2 (25 mL) and water (25 mL), then extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with saturated NaCl, dried over Na2SO4, filtered and evaporated in vacuo. The product 7 was purified by column chromatography.

The synthesis of dienophiles 8 and 9

A solution of N-substituted anilines (4 or 6, 1.0 equiv.) in methylene chloride (10 mL) and water (10 mL) was stirred at 0 °C, and 25% NaOH (2 mL for 1 mmol 2-chloroethanesulfonyl chloride) and 2-chloroethanesulfonyl chloride (1.2 equiv.) were added simultaneously and slowly under 0 °C, keeping the pH between 8.5 and 9.5. After 12 h, the mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with saturated NaCl and dried with Na2SO4, filtered, evaporated in vacuo, and purified by flash chromatography on silica gel to give the dienophiles 8 and 9.

General procedure for the Diels–Alder reaction of dienophiles 7–9 and 10

3,4-Diphenol furans 10 (1.0 equiv.) and dienophiles 7–9 (1.2 equiv.) were placed in a round flask, and the mixture was stirred under Ar2 atmosphere at 95 °C for 24 h. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography (EtOAc–petroleum ether = 1 : 3).

5,6-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-N-phenyl-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11a)

Yellow solid (69% yield; mp 94–96 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.82 (s, 1H), 8.68 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.34–7.27 (m, 2H), 7.20–7.08 (m, 3H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.77 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 4H), 6.73 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 5.48 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 1H), 5.31 (dd, J = 4.4, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 3.49 (dd, J = 8.4, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.30 (dt, J = 12.0, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 1.98 (dd, J = 12.4, 8.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.26, 158.17, 139.34, 138.27, 130.18, 129.66, 129.46, 125.26, 125.08, 124.53, 121.56, 121.49, 116.43, 116.37, 85.03, 83.62, 68.10, 26.18; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C24H21NO5SNa, 458.1031 (M + Na+); found, 458.10327.

5,6-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-7-oxabicyclo-[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11b)

Yellow solid (73% yield; mp 96–98 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.70 (s, 1H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.83 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.77 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.7 Hz, 4H), 5.48 (s, 1H), 5.30 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 3.39 (dd, J = 8.4, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.28 (dt, J = 12.1, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 1.69 (dd, J = 11.5, 4.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.24, 158.21, 141.84, 138.34, 131.58, 129.77, 129.50, 125.21, 125.15, 124.87, 124.78, 116.49, 116.39, 115.22, 85.10, 83.59, 61.80, 55.74, 20.93; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C25H23NO6SNa, 488.1135 (M + Na+); found, 488.11383.

N-(2-Chlorophenyl)-5,6-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-7-oxabicyclo-[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11c)

Yellow solid (65% yield; mp 93–95 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.70 (s, 1H), 8.38 (s, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H), 7.36–7.29 (m, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 7.09 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 6.77 (dd, J = 8.7, 7.1 Hz, 4H), 5.49 (s, br, 1H), 5.34 (dd, J = 4.4, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (dd, J = 8.0, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 2.36 (dt, J = 12.0, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 1.98–1.96 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.29, 158.18, 142.12, 138.26, 135.54, 135.46, 130.71, 129.66, 129.57, 128.77, 127.26, 125.39, 125.31, 124.47, 116.45, 116.37, 85.15, 83.65, 63.80, 18.85; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C24H20NO5SClNa, 492.0656 (M + Na+); found, 492.06429.

N-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5,6-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-7-oxabicyclo-[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11d)

Yellow solid (72% yield; mp 121–123 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.96 (s, 1H), 8.72 (s, 1H), 7.40–7.37 (m, 2H), 7.34–7.31 (m, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.76 (dd, J = 8.7, 6.0 Hz, 4H), 5.47 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 1H), 5.31 (dd, J = 4.4, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 3.52 (dd, J = 8.4, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.28 (dt, J = 12.0, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.02 (dd, J = 8.7, 3.3 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.27, 158.17, 141.95, 138.18, 130.10, 130.01, 129.64, 129.51, 125.04, 124.50, 123.09, 123.02, 116.43, 116.36, 85.03, 83.62, 62.65, 18.85; HRMS calcd for C24H20NO5SClNa, 492.0643 (M + Na+); found, 492.06429.

5,6-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-N-methyl-N-phenyl-7-oxabicyclo-[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11e)

Yellow solid (71% yield; mp 86–88 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.71 (s, 1H), 8.67 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.35 (dd, J = 8.0, 3.0 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.13 (m, 4H), 6.79 (dd, J = 10.9, 8.6 Hz, 4H), 5.45 (s, 1H), 5.29 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (dd, J = 8.1, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.39 (s, 3H), 2.43–2.27 (m, 1H), 1.97 (dd, J = 8.2, 3.7 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.31, 158.25, 141.88, 138.27, 130.40, 129.80, 129.77, 129.49, 127.66, 127.37, 125.17, 124.59, 116.50, 116.34, 85.24, 83.61, 61.71, 39.18, 18.84; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C25H23-NO5SNa, 472.1191 (M + Na+); found, 472.11892.

5,6-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11f)

Yellow solid (73% yield; 89–91 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.70 (s, 1H), 8.64 (s, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (dd, J = 8.6, 3.4 Hz, 4H), 6.86 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.78 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 5.45 (s, br, 1H), 5.30 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.53 (dd, J = 8.3, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.33 (s, 3H), 2.16 (dt, J = 11.8, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.01 (dd, J = 8.8, 3.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 159.49, 158.31, 158.22, 141.85, 138.30, 135.61, 129.89, 129.48, 129.20, 125.22, 124.64, 116.58, 116.41, 114.94, 85.31, 83.63, 60.67, 55.79, 32.66, 20.93; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C26H25NO6SNa, 502.1282 (M + Na+); found, 502.12948.

N-(2-Chlorophenyl)-5,6-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-N-methyl-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11g)

Yellow solid (77% yield; mp 97–99 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.70 (s, 1H), 8.67 (s, 1H), 7.52 (ddd, J = 7.2, 6.3, 4.3 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (ddd, J = 6.4, 3.4, 2.2 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (dd, J = 8.7, 3.3 Hz, 4H), 6.81 (dd, J = 8.6, 7.2 Hz, 4H), 5.56 (s, br, 1H), 5.36 (dd, J = 4.4, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 3.68 (dd, J = 8.3, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.29 (s, 3H), 2.36 (dt, J = 11.1, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 2.20 (dd, J = 11.9, 8.3 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.29, 158.21, 140.11, 138.46, 134.96, 132.74, 131.33, 130.64, 130.39, 129.91, 129.49, 128.88, 125.26, 124.61, 116.52, 116.36, 85.42, 83.68, 60.62, 39.33, 18.85; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C25H22NO5SClNa, 506.0787 (M + Na+); found, 506.07994.

N-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5,6-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-N-methyl-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11h)

Yellow solid (71% yield; mp 86–88 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ = 8.70 (s, 1H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 8.8, 2H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.7, 2H), 7.17 (t, J = 8.6, 4H), 6.80 (dd, J = 12.7, 8.6, 4H), 5.46 (s, 1H), 5.30 (d, J = 4.2, 1H), 3.60 (dd, J = 8.3, 4.5, 1H), 3.39 (s, 3H), 2.42–2.31 (m, 1H), 2.27 (dd, J = 8.6, 4.7, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.32, 158.26, 142.00, 138.14, 132.70, 130.43, 130.31, 129.81, 129.52, 128.83, 125.10, 124.54, 116.55, 116.39, 85.24, 83.67, 60.56, 39.15, 20.94; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C25H22NO5SClNa, 506.0793 (M + Na+); found, 506.07994.

N-Ethyl-5,6-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-N-phenyl-7-oxabicyclo-[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11i)

Yellow solid (75% yield; mp 102–104 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.72 (s, 1H), 8.67 (s, 1H), 7.37–7.33 (m, 4H), 7.33–7.30 (m, 1H), 7.19 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.7 Hz, 4H), 6.80 (dd, J = 14.2, 8.6 Hz, 4H), 5.47 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H), 5.31 (dd, J = 4.4, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.51 (dd, J = 8.3, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.17 (dt, J = 11.9, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.05–2.00 (m, 1H), 1.03 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.35, 158.24, 140.32, 138.33, 130.40, 130.10, 129.91, 129.89, 129.44, 128.40, 125.21, 124.57, 116.56, 116.37, 85.30, 83.63, 62.59, 47.10, 18.86, 14.94; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C26H25NO5SNa, 486.1334 (M + Na+); found, 486.13457.

N-Ethyl-5,6-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11j)

Yellow solid (71% yield; mp 92–93 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.85 (s, 1H), 8.79 (s, 1H), 7.25 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 4H), 6.89–6.76 (m, 6H), 5.46 (s, 1H), 5.31 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.76 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 3.47 (dd, J = 7.7, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 2.20 (dt, J = 8.9, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 1.72 (dd, J = 13.8, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 1.03 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 159.90, 158.22, 141.83, 138.43, 132.65, 131.99, 131.51, 129.97, 129.39, 125.28, 124.64, 116.56, 116.36, 114.95, 85.34, 83.59, 62.29, 55.74, 47.29, 31.29, 14.90; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C27H27NO6SNa, 516.1450 (M + Na+); found, 516.14513.

N-(2-Chlorophenyl)-N-ethyl-5,6-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11k)

Yellow solid (68% yield; mp 92–94 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.78 (s, 1H), 8.75 (s, 1H), 7.51 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (dd, J = 9.1, 4.1 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H), 6.80 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 4H), 5.53 (s, 1H), 5.34 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (dd, J = 22.3, 14.8 Hz, 2H), 3.62 (dd, J = 8.1, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.30–2.24 (m, 1H), 2.20 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 1.06 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.39, 158.29, 142.09, 139.71, 138.50, 137.38, 134.30, 131.36, 130.69, 129.93, 129.42, 128.56, 125.26, 124.59, 116.55, 116.38, 85.50, 83.65, 64.10, 47.05, 32.66, 14.580; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C26H24NO5SClNa, 520.0960 (M + Na+); found, 520.09559.

N-(4-Chlorophenyl)-N-ethyl-5,6-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11l)

Yellow solid (69% yield; mp 107–109 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.70 (s, 1H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 4H), 7.19 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.7 Hz, 4H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.78 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 5.48 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H), 5.32 (dd, J = 4.3, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.53 (dd, J = 8.3, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.27 (dd, J = 13.0, 7.1 Hz, 1H), 2.15 (dt, J = 11.9, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 1.04 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.34, 158.24, 141.87, 139.21, 138.24, 133.54, 131.59, 129.92, 129.90, 129.47, 125.17, 124.57, 116.57, 116.39, 85.29, 83.65, 62.90, 47.06, 20.94, 14.85; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C26H24NO5SClNa, 520.0953 (M + Na+); found, 520.09559.

5,6-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-N-phenyl-N-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11m)

Yellow solid (59% yield; mp 91–93 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.76 (s, 1H), 8.70 (s, 1H), 7.48–7.45 (m, 2H), 7.36 (dd, J = 5.2, 2.0 Hz, 3H), 7.19 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 2H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.78 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 5.53 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 1H), 5.33 (dd, J = 4.3, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 4.59 (q, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 3.58 (dd, J = 8.3, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.50–2.40 (m, 1H), 2.14 (dd, J = 8.2, 3.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.47, 158.32, 142.10, 140.54, 138.07, 130.19, 130.04, 129.85, 129.35, 129.18, 125.03, 124.36, 116.56, 116.36, 85.20, 83.59, 62.99, 60.59, 30.62; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C26H22NO5-SF3Na, 540.1076 (M + Na+); found, 540.10630.

5,6-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11n)

Yellow solid (80% yield; 117–119 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.80 (s, 1H), 8.73 (s, 1H), 7.35–7.32 (m, 2H), 7.19 (dd, J = 8.6, 6.6 Hz, 4H), 6.85 (t, J = 9.1 Hz, 4H), 6.78 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 5.52 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H), 5.33 (dd, J = 4.3, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (q, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.55–3.53 (m, 1H), 2.50–2.41 (m, 1H), 2.17 (dd, J = 8.2, 3.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 160.37, 158.45, 158.27, 142.10, 138.13, 132.78, 131.29, 130.16, 129.33, 125.11, 124.45, 116.59, 116.37, 115.21, 85.25, 83.57, 62.62, 60.59, 55.79, 31.37; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C27H24NO6SF3Na, 570.1173 (M + Na+); found, 570.11687.

N-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5,6-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-N-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11o)

Yellow solid (69% yield; mp 93–95 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone- d6) δ 8.80 (s, 1H), 8.73 (s, 1H), 7.33 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (dd, J = 8.6, 6.6 Hz, 4H), 6.85 (t, J = 9.1 Hz, 4H), 6.78 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 5.52 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H), 5.33 (dd, J = 4.3, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (q, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 3.56–3.53 (m, 2H), 2.50–2.41 (m, 1H), 2.17 (dd, J = 8.2, 3.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.41, 158.37, 142.14, 139.40, 137.98, 134.43, 131.46, 130.24, 130.02, 129.37, 124.95, 124.35, 116.56, 116.37, 85.22, 83.61, 63.38, 60.59, 31.37; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C26H21NO5SF3ClNa, 574.0665 (M + Na+); found, 574.06733.

N-Ethyl-5,6-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-N-(naphthalen-2-yl)-7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-sulfonamide (11p)

Yellow solid (71% yield; mp 165–167 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 8.80 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.32 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.82–6.68 (m, 6H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 5.32 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 5.27 (s, br, 1H), 3.66 (dd, J = 8.3, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 3.47 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.41 (dt, J = 11.8, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 1.89 (dd, J = 11.8, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 1.39 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 158.28, 157.92, 150.59, 141.99, 138.45, 134.76, 131.66, 129.88, 129.02, 128.84, 125.95, 125.53, 125.11, 124.59, 123.95, 122.89, 120.67, 116.41, 116.31, 116.22, 101.72, 85.01, 83.83, 65.83, 38.91, 14.28; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C30H27NO5SNa, 536.1513 (M + Na+); found, 536.15022.

Estrogen receptor binding assays

Relative binding affinities were determined by a competitive radiometric binding assay, as previously described,29 using 2 nM [3H]estradiol as tracer (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) and purified full-length human ERα and ERβ (PanVera/InVitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Incubations were for 18–24 h at 0 °C. Then the receptor–ligand complexes were absorbed onto hydroxyapatite (BioRad, Hercules, CA), and unbound ligand was washed away. The binding affinities are expressed as relative binding affinity (RBA) values, with the RBA of estradiol set to 100. The values given are the average ± range or SD of two or more independent determinations. Estradiol binds to ERα with a Kd of 0.2 nM and to ERβ with a Kd of 0.5 nM.

Luciferase reporter gene assays

HepG2 cells cultured in Dulbecco’s minimum essential medium (DMEM) (Cellgro by Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone by Thermo Scientific, South Logan, UT), and 1% non-essential amino acids (Cellgro), Penicillin–Streptomycin–Neomycin antibiotic mixture and Glutamax (Gibco by Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were transfected with 10 μg of 3X ERE-luciferase reporter plus 1.6 μg of ERα or ERβ expression vector per 10 cm dish using FugeneHD reagent (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN). The next day, the cells were transferred to phenol red-free growth media supplemented with 10% charcoal-dextran sulfate-stripped FBS at a density of 20 000 cells per well, incubated in 384-well plates overnight at 37 °C and 5% CO2, and stimulated with various concentrations of compounds in triplicate. Luciferase activity was measured after 24 h using BriteLite reagent (Perkin-Elmer Inc., Shelton, CT) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the NSFC (91017005, 20972121, 81172935), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-10-0625), the National Mega Project on Major Drug Development (2009ZX09301-014-1), and the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (20100141110021) for support of this research. Research support from the National Institutes of Health (PHS 5R37 DK015556 to J.A.K. and R01 DK077085 to K.W.N.) is gratefully acknowledged. We are grateful to Teresa Martin to help in the binding assays.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Synthetic procedures and characterization of compounds 7–9, and 1H NMR assignment of exo 11. See DOI: 10.1039/c2ob26531a

Contributor Information

Manghong Zhu, Email: zhouhb@whu.edu.cn.

John A. Katzenellenbogen, Email: jkatzene@illinois.edu.

Kendall W. Nettles, Email: knettles@scripps.edu.

Notes and references

- 1.Jordan VC. Sci Am. 1998:60–67. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1098-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:335–344. doi: 10.1186/bcr78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grese TA, Dodge JA. Curr Pharm Des. 1998;4:71–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shang YF, Brown M. Science. 2002;295:2465–2468. doi: 10.1126/science.1068537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black LJ, Sato M, Rowley E, Magee D, Bekele A, Williams D, Cullinan G, Bendele R, Kauffman R, Bensch W. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:63. doi: 10.1172/JCI116985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordan VC. J Med Chem. 2003;46:883–908. doi: 10.1021/jm020449y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan VC. J Med Chem. 2003;46:1081–1111. doi: 10.1021/jm020450x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonnell DP, Wardell SE. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dauvois S, Danielian PS, White R, Parker MG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4037–4041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smolnikar K. Drugs Today (Barc) 2001;37:783–789. doi: 10.1358/dot.2001.37.11.844211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brzozowski AM, Pike AC, Dauter Z, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, et al. Nature. 1997;389:753–758. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiau AK, Barstad D, Loria PM, Cheng L, Kushner PJ, Agard DA, Greene GL. Cell. 1998;95:927–937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muthyala RS, Sheng SB, Carlson KE, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. J Med Chem. 2003;46:1589–1602. doi: 10.1021/jm0204800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamann LG, Meyer JH, Ruppar DA, Marschke KB, Lopez FJ, Allegretto EA, Karanewsky DS. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:1463–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sibley R, Hatoum-Mokdad H, Schoenleber R, Musza L, Stirtan W, Marrero D, Carley W, Xiao H, Dumas J. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:1919–1922. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou HB, Comninos JS, Stossi F, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7261–7274. doi: 10.1021/jm0506773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng Y, Zhu M, Srinivasan S, Nwachukwu JC, Cavett V, Min J, Carlson KE, Wang P, Dong C, Katzenellenbogen JA, Nettles KW, Zhou HB. ChemMedChem. 2012;7:1094–1100. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nettles KW, Bruning JB, Gil G, Nowak J, Sharma SK, Hahm JB, Kulp K, Hochberg RB, Zhou H, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Kim Y, Joachmiak A, Greene GL. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:241–247. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiau AK, Barstad D, Radek JT, Meyers MJ, Nettles KW, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA, Agard DA, Greene GL. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:359–364. doi: 10.1038/nsb787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forgione P, Wilson PD, Fallis AG. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu SJ, Zhou B, Yang HY, He YT, Jiang ZX, Kumar S, Wu L, Zhang ZY. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8251–8260. doi: 10.1021/ja711125p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris J, Wishka DG. J Org Chem. 1991;56:3549–3556. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohtaka J, Sakamoto T, Kikugawa Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:1681–1683. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salazar J, Lepez SE, Rebollo O. J Fluorine Chem. 2003;124:111–113. [Google Scholar]

- 25.La Regina G, Silvestri R, Gatti V, Lavecchia A, Novellino E, Befani O, Turini P, Agostinelli E. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:9729–9740. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato S, Watanabe H, Asami M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2000;11:4329–4340. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou HB, Nettles KW, Bruning JB, Kim Y, Joachimiak A, Sharma S, Carlson KE, Stossi F, Katzenellenbogen BS, Greene GL, Katzenellenbogen JA. Chem Biol. 2007;14:659–669. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng YY, Liu HL, Tang M, Cai LS, Pike V. Chin J Chem. 2009;27:1339–1344. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlson KE, Choi I, Gee A, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1997;36:14897–14905. doi: 10.1021/bi971746l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonnell DP, Connor CE, Wijayaratne A, Chang CY, Norris JD. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002;57:295–316. doi: 10.1210/rp.57.1.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McInerney EM, Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW, Katzenellenbogen BS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10069–10073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anstead GM, Carlson KE, Katzenellenbogen JA. Steroids. 1997;62:268–303. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(96)00242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pike AC, Brzozowski AM, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Thorsell AG, Engstrom O, Ljunggren J, Gustafsson JA, Carlquist M. Embo J. 1999;18:4608–4618. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.