Abstract

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer in which patients with metastatic disease have a five year survival-rate of less than 10%. Recently the over expression of a beta galactoside binding protein, galectin-3 (LGALS3), has been correlated with metastatic melanoma in patients. We have previously shown that silencing galectin-3 in metastatic melanoma cells reduces tumor growth and metastasis. Gene expression profiling identified the pro-tumorigenic gene autotaxin (ENPP2) to be down regulated after silencing galectin-3. Here we report that galectin-3 regulates autotaxin expression at the transcriptional level by modulating the expression of the transcription factor NFAT1 (NFATC2). Silencing galectin-3 reduced NFAT1 protein expression which resulted in decreased autotaxin expression and activity. Reexpression of autotaxin in galectin-3 silenced melanoma cells rescues angiogenesis, tumor growth and metastasis in vivo. Silencing NFAT1 expression in metastatic melanoma cells inhibited tumor growth and metastatic capabilities in vivo. Our data elucidate a previously unidentified mechanism by which galectin-3 regulates autotaxin, and assign a novel role for NFAT1 during melanoma progression.

Introduction

Galectins are a family of carbohydrate binding proteins that bind with a high affinity to β-galactoside sugars (1). Of these carbohydrate-binding proteins, galectin-3 has a unique chimeric molecular structure which consists of 3 domains: an NH2-terminal domain, a proline, glycine, and tyrosine-rich domain, and a COOH-terminal carbohydrate-binding domain (1). The NH2-terminal domain is post translationally modified via phosphorylation at ser6 by casein kinase 1 and this controls its cellular compartmentalization, transcriptional regulation of specific genes, anti-apoptotic function, and its carbohydrate binding properties (2, 3). Both MMP-2 and MMP-9 cleave extracellular galectin-3 in the intermediate domain, and a NWGR “anti-death” motif within its carbohydrate binding domain inhibits Cytochrome C release and apoptosis in cancer cells (4, 5). Along with binding to N-glycosylated surface proteins, galectin-3 has been reported to form intracellular protein complexes with different molecules to induce K-Ras nanoclustering, WNT / β-catenin signaling, or mRNA spliseosome complexes (6–8).

In cancers, increased expression of galectin-3 has been correlated with the progression of glioma, melanoma, thyroid, pancreatic, and breast cancer (9–13). Its expression in breast cancer cells contributes to the up regulation of cell cycle molecules such as Cyclin D1, and chemotherapeutic insults in breast cancer cells induces phosphorylation of galectin-3 which translocates it to the cytoplasm to inhibit Cytochrome C release and apoptosis (13, 14). Cleavage of galectin-3 by MMP-2 within the tumor microenvironment has been reported to induce angiogenesis, and exogenous galectin-3 increases capillary tube formation of endothelial cells in a carbohydrate binding dependent manner (15). As we reported previously, this phenomenon has also been identified in the C8161 melanoma cell line by a different mechanism, i.e. by regulating VE-Cadherin expression (16). Silencing galectin-3 in C8161 cells also reduced the pro-angiogenic chemokine IL-8 and MMP-2, indicating its role in invasion and metastasis (16). Indeed, C8161 melanoma cells transduced with galectin-3 shRNA significantly decreases experimental lung metastasis (16). Furthermore, mice fed with Modified Citrus Pectin, a carbohydrate binding inhibitor of galectin-3, significantly reduced spontaneous metastasis of MDA-MB-431 breast cancer cells (17).

In the present study, we sought out to identify novel downstream molecules that are regulated by galectin-3 which contribute to melanoma growth and metastasis. To that end, we stably transduced WM2664 and A375SM metastatic melanoma cell lines with lentiviral based short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting galectin-3. These cells were subjected to gene expression profiling. Of the genes deregulated by galectin-3 shRNA, we identified a down regulation of autotaxin. Autotaxin was originally identified as a motility factor in A2058 melanoma cells (18). The mechanism in which autotaxin induced motility remained elusive until it was identified that its phosphodiesterase catalytic site was required to enhance cell migration (19). It was later realized that autotaxin was identical to lysophospholipase D purified from fetal bovine serum which catalyzes lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) to the bioactive lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) (20). LPA acts as a ligand for three of the EDG family G-protein coupled receptors, LPA1, LPA2, and LPA3, or the non EDG GPCRs that belong in the purinergic receptor family such as LPA4, LPA5, LPA6 to induce downstream signaling which promotes chemotaxis, migration, invasion, angiogenesis, and tumorigenesis of multiple types of cancers (21–23). A strong enhancer of autotaxin expression in cancer is the transcription factor Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells (NFAT1). Here we report that silencing galectin-3 decreases the protein expression of NFAT1 which reduces the transcriptional activation of autotaxin in melanoma cells, thus decreasing melanoma growth and metastasis. Our data unravel a novel mechanism by which galectin-3 contributes to the acquisition of the melanoma metastatic phenotype by enhancing autotaxin expression. Our studies also assign a mechanistic role for NFAT1 in melanoma growth and metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

The A375SM melanoma cell line was established through intravenous injection of A375-P in which the pooled lung metastasis were collected and grown. The WM2664 melanoma cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, and is highly metastatic in nude mice. The non-metastatic SB-2 melanoma cell line was isolated from a primary cutaneous lesion. The culture conditions for the melanoma cell lines and the 293T cells were previously described (24). Cells were tested and authenticated by STR.

Lentiviral expression vectors, shRNA, and siRNA

galectin-3 shRNA was prepared as previously described (16). Briefly, galectin-3 targeting shRNA 5′-GTACAATCATCGGGTTAAA-3′ and Non Targeting shRNA 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′ were designed with a hairpin and inserted into a pLVTHm lentiviral vector. Galectin-3, autotaxin and NFAT1 genes were cloned from A375SM cDNA. Either gene was cut with the designated restriction enzymes (Table S1), inserted into a PcDH vector and packaged in a lentiviral virus. The galectin-3 shRNA targeting site was mutated to ATATAACCACCGTGTCAA (underlined nucleotide designates mutated sites). Transduction methods into melanoma cells were performed as previously described (16). NFAT1 siRNA was purchased from Sigma and transfected into WM2664 and A375SM melanoma cells by using HiPerFect Transfection Reagent (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The siRNA sequence from Sigma targeting 5′-CTGATGAGCGGATCCTTAA-3′ was used to stably silence NFAT1 by inserting it or NT shRNA into a PcDH vector and packaged within the lentiviral system as described above.

Western Blot Analysis

To detect galectin-3 and NFAT1, 20ug of whole cell protein lysate was loaded on SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. To detect autotaxin protein expression, 1.5 million cells were plated in a 10cm dish and were incubated with 8ml of serum free MEM for 48hrs. The supernatant from cell culture was concentrated to 100ul, was protein precipitated as previously described, and resuspended in 6M urea lysis buffer (24). Blots were incubated with primary antibodies rabbit polyclonal anti-galectin-3; anti-NFAT1 Santa Cruz Biotechnology; anti-autotaxin Abcam. To confirm equal loading of the supernatant, the membrane was coomassie blue stained and destained with 40% methanol, 60% water, and 10% acetic acid until protein bands were visible. Replicates of westerns were analyzed by densitometry and the mean and S.D. are shown as bar graphs underneath the corresponding blots.

Semi quantitative RT-PCR

Isolation of RNA was performed with the RNAqueous kit (Ambion) and reverse transcribed with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Real time PCR was performed with the autotaxin Taqman Gene Expression Assay and standardized to 18s (Applied Biosystems).

Autotaxin Activity Assay

To analyze autotaxin lysophospholipase D activity, the fluorescent compound FS-3 (L-2000; Echelon) was used as previously described (25). A volume of 25 ul supernatant and 25 ul 2x loading buffer for each sample were run on SDS-PAGE and silver stained with Silverquest™ Silver Staining Kit (LC6070; Invitrogen) to confirm equal total protein concentration.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

ChIP assays were performed with the ChIP-IT Express Enzymatic kit (53009; Active Motive) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and as previously described (24). Fixed protein DNA complexes were pulled down with anti-NFAT1 antibody (sc-7296; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), were Protein-DNA reverse cross-linked, and prepared for PCR. PCR was performed surrounding both NFAT1 binding sites.

Reporter Constructs and Luciferase Activity Analysis

The autotaxin promoter was cloned from A375SM melanoma cells to encompass 930 base pairs upstream of the transcriptional initiation site. Direct site mutagenesis of NFAT1 binding sites were carried out using QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Transfection with Lipofectin (Invitrogen) was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. The Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence

Anti-CD31 staining was used in mouse frozen sections to identify tumor blood vessels. TUNEL staining was performed using the DeadEnd Fluoremetric TUNEL system (Promega) with paraffin sections according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Tumor Growth and Metastasis

Female Athymic Balb/c nude mice were purchased from Tanomics and were housed in pathogen free conditions. All studies were approved and supervised by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). For the tumor growth model, 1×106 cells were injected subcutaneously and tumor size was monitored twice a week for 27 days for galectin-3 shRNA and 32 days for NFAT1 shRNA studies. Ten mice per group and eight mice per group for galectin-3 and NFAT1 in vivo studies respectively were used. Mice were then sacrificed and tumors were collected. For experimental lung metastasis, eight mice per group were sacrificed four weeks after 5×105 cells were injected intravenously as previously described (24).

Expression Microarray

Total RNA was isolated from WM 2664 NT and galectin-3 shRNA melanoma cells. RNA was converted into cRNA using the Illumina TotalPrep Amplificatin Kit (Ambion) and hybridized in triplicate to the HT-12 Version 3 Illumina chip. Gene expression analysis was performed between the two samples.

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test was performed for the analysis of in vitro assays +/−SE. The Mann-Whitney U test was performed for statistical analysis of the in vivo tumor growth and metastasis results.

Results

Silencing Galectin-3 Decreases Autotaxin Expression

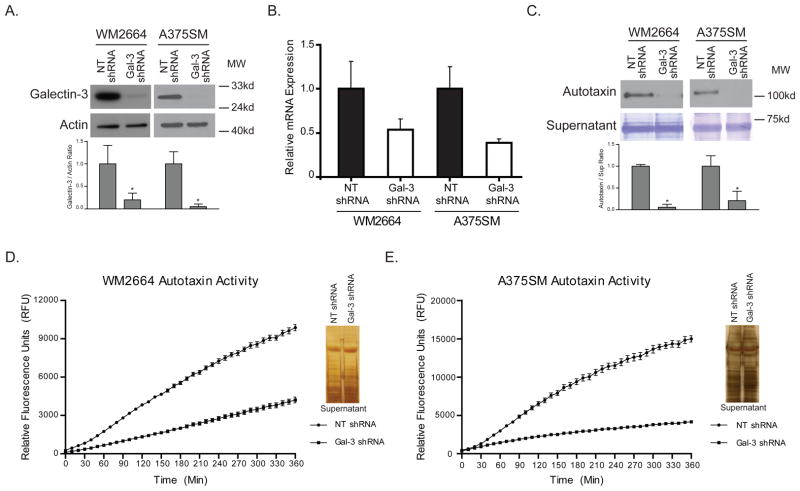

We have previously reported that galectin-3 expression is increased in highly metastatic melanoma cell lines and tissue specimens (10). To further investigate how galectin-3 contributes to melanoma progression, we stably silenced galectin-3 by greater than 80% in two metastatic human melanoma cell lines, WM2664 and A375SM (Figure 1A). We then corroborated that silencing galectin-3 reduces the migratory and invasive phenotype of melanoma cells in vitro (Supplemental Figure S1A and B) Furthermore, silencing galectin-3 significantly reduced their ability to grow in soft agar, indicating that galectin-3 plays a role in anchorage independent growth (Supplemental Figure S1C).

Figure 1. Autotaxin expression is decreased in melanoma cells after silencing galectin-3.

(A) More than 80% of galectin-3 protein within WM2664 and A375SM melanoma cells is silenced with Lentiviral galectin-3 shRNA (*P < 0.05). (B) Relative mRNA expression is decreased by approximately 2 fold in WM2664 cells and 2.4 fold in A375SM melanoma cells after silencing galectin-3. (C) Protein expression of autotaxin within the supernatant is drastically reduced by more than 5 fold in both cell lines after galectin-3 silencing (*P < 0.05). Coomassie blue staining is shown for equal loading. The higher rate of fluorescent activity indicates a higher rate of FS-3 cleavage by autotaxin. As compared to NT shRNA, silencing galectin-3 (Gal-3 shRNA) decreases the fluorescent activity within the supernatant of both (D) WM2664 and (E) A375SM melanoma cells. A silver stain was performed with equal volumes of supernatant as a loading control.

Next, we sought to identify whether galectin-3 can regulate the expression of genes that play a role in migration, invasion, and cell growth. To that end, WM2664 melanoma cells were subjected to Illumina gene expression microarray analysis by which we identified the pro tumorigenic gene autotaxin to be down regulated by 2.5 fold after silencing galectin-3. It has previously been reported that autotaxin enhances invasion and induces tumorigenesis in mice (20, 26). Therefore, galectin-3 can have a pro-tumor effect by modulating the expression of autotaxin during melanoma progression. To confirm our initial microarray studies, qRT-PCR was performed on both WM2664 and A375SM melanoma cells after silencing galectin-3. Autotaxin mRNA expression is decreased by 2 – 2.5 fold in both cell lines, thus corroborating the cDNA microarray analysis (Figure 1B). Autotaxin is primarily a secreted protein where it performs its enzymatic function by converting LPC to LPA. Therefore, we collected the supernatant from the galectin-3 silenced melanoma cell lines and we observed less protein secretion of autotaxin by more than 5 fold in both melanoma cell lines as compared to control cells (Figure 1C). The fold decrease in the secreted autotaxin was much higher than the 2.5 fold decrease observed in the cDNA microarray.

Decreased Autotaxin Activity is Observed after Silencing Galectin-3

As autotaxin is a lysophospholypase D enzyme, converting LPC to LPA, we next sought to evaluate the effect of silencing galectin-3 on autotaxin activity. To that end, a fluorescent compound, FS-3, was used. FS-3 resembles LPC, the natural substrate of autotaxin, and is cleaved by autotaxin to release the fluorescence from the quencher (27). Therefore, in the presence of higher concentrations of autotaxin, we expect to see a faster rate of FS-3 cleavage and higher fluorescent activity. Indeed, supernatant from NT shRNA transduced WM2664 and A375SM cells have a higher rate of FS-3 cleavage as compared to galectin-3 shRNA transduced cells (Figure 1D, and 1E). Therefore, we conclude that silencing galectin-3 reduces LPA production within the tumor microenvironment by decreasing autotaxin expression..

Galectin-3 Regulates Autotaxin Expression at the Transcriptional Level

To determine whether the regulation of autotaxin is transcriptionally or post-transcriptionally regulated, a nuclear run-on assay was performed with the A375SM melanoma cells after silencing galectin-3. A significant decrease in the mRNA expression of autotaxin was identified after silencing galectin-3 indicating that autotaxin is regulated at the transcriptional level (Supplemental Figure S2A). To corroborate these results, the promoter of autotaxin was inserted into a PGL3 luciferase reporter vector and transiently transfected in WM2664 and A375SM melanoma cells. Luciferase reporter activity was reduced in melanoma cell lines transduced with galectin-3 shRNA (Supplemental Figure S2B and C). These data suggest that galectin-3 shRNA down regulates autotaxin expression at the transcriptional level.

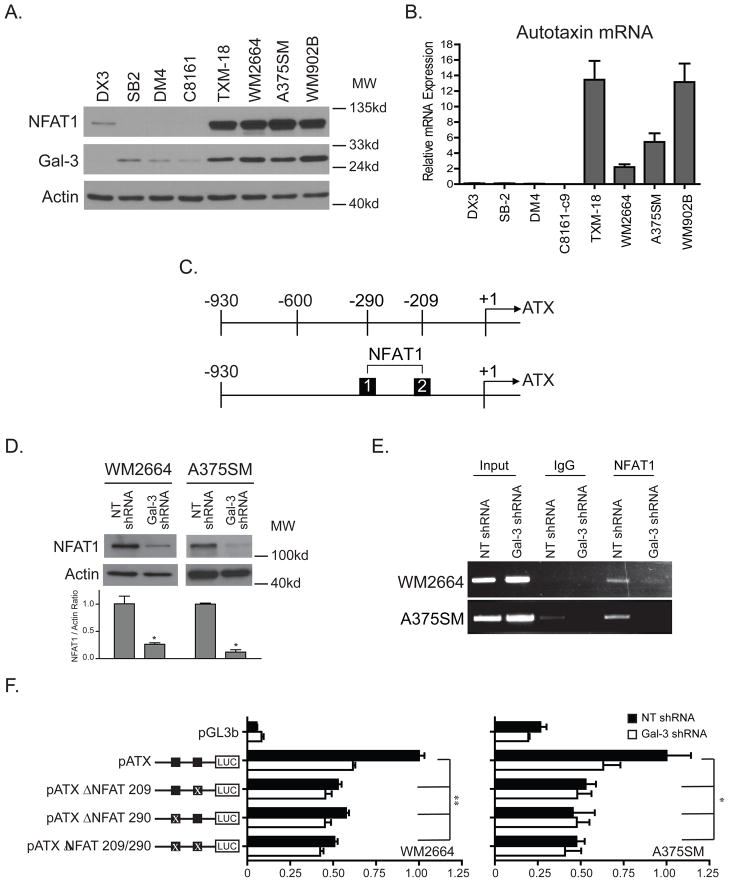

Galectin-3 Silencing Decreases the Protein Levels of NFAT1: A Transcriptional Regulator of Autotaxin

The transcription factor NFAT1 has previously been reported to bind to the autotaxin Promoter (28). Therefore, we decided to focus on NFAT1 in our studies. To that end, we first analyzed the protein expression status of NFAT1 in several melanoma cell lines with different metastatic potential. We identified that NFAT1 protein expression is positively correlated with galectin-3 (Figure 2A). Interestingly, only the highly metastatic melanoma cell lines that have high levels of NFAT1 and galectin-3 express autotaxin (Figure 2B). NFAT1 expression in DX3 is evident, however, its expression is low, likely due to the cells lacking galectin-3, and this results in no autotaxin expression (Figure 2A and B). Two NFAT1 binding sites are located within 300bp from the transcription initiation site of autotaxin at approximately positions −290 and −209 respectively (Figure 2C). It is likely that galectin-3 drives the expression of NFAT1, which binds to the autotaxin promoter. Therefore, we investigated the status of NFAT1 expression after silencing galectin-3. NFAT1 protein expression was significantly reduced by 3.8 and 8.5 fold in both WM2664 and A375SM cell lines respectively, p < 0.05 (Figure 2D). To determine whether NFAT1 directly affects autotaxin expression at the transcriptional level, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) targeting the NFAT1 transcription factor identified that NFAT1 binds to the autotaxin promoter, and silencing galectin-3 decreased the amount of NFAT1 binding in both cell lines (Figure 2E).

Figure 2. Effect of galectin-3 silencing on NFAT1 expression and binding to the Autotaxin promoter.

(A) A melanoma cell panel depicting the positive correlation between NFAT1 and galectin-3 protein expression. (B) Autotaxin mRNA expression in the same cell panel is only expressed in cell lines with high galectin-3 and NFAT1 expression. (C) Two NFAT1 binding sites are located within 300bp upstream of the autotaxin transcription start site. (D) Silencing galectin-3 significantly reduces total NFAT1 protein expression in WM2664 and A375SM melanoma cells (*P < 0.05). (E) This leads to a reduction in NFAT1 binding to the autotaxin promoter as observed by ChIP in both cell lines. (F) Mutations at either NFAT1 binding site reduce the luciferase promoter activity to the same levels as galectin-3 shRNA melanoma cells (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05). Double mutations do not have an additive effect, indicating that both sites are critical for autotaxin transcription.

To further establish autotaxin regulation by NFAT1, the autotaxin promoter was cloned in a PGL3 vector with mutations at either single or both NFAT1 binding sites. Luciferase activity after mutating either NFAT1 binding site was decreased by approximately 50% in both melanoma cell lines (Figure 2F). This is comparable to the luciferase activity of the autotaxin promoter after silencing galectin-3. However, mutating both binding sites did not have an additive effect, concluding that both binding sites are equally required for NFAT1 transcriptional activity.

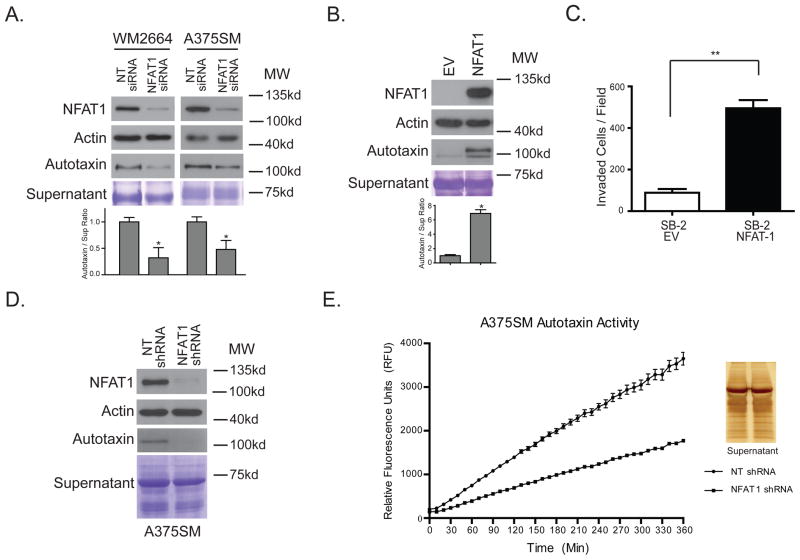

Silencing NFAT1 Decreases Autotaxin Protein Expression

To corroborate our initial studies that NFAT1 is responsible for autotaxin expression, we transiently silenced NFAT1 with siRNA in WM2664 and A375SM parental cell lines. We achieved approximately 90% silencing of NFAT1 in these cells. This resulted in decreased expression of autotaxin within the supernatant (Figure 3A). Furthermore, enforced expression of NFAT1 in SB-2 melanoma cells (non-metastatic, NFAT1 negative) induces the expression of autotaxin by approximately 6 fold (Figure 3B) and significantly enhanced their invasive potential in Matrigel coated filters (Figure 3C). A second band is seen underneath autotaxin, and could be one of the shorter isoforms 2 or 3. However, the larger band appears to be isoform 1. Interestingly, the smaller isoform is only seen in the SB-2 melanoma cells and not in the more metastatic cell lines. In addition, stable NFAT1 silencing with shRNA in A375SM cells also diminishes autotaxin expression at the mRNA and protein level (Supplemental Figure S3 and Figure 3D) which results in reduced FS-3 fluorescence (Figure 3E).

Figure 3. NFAT1 regulates Autotaxin protein expression in melanoma cells.

(A) Transient silencing of NFAT1 in WM2664 and A375SM melanoma cells reduces autotaxin expression by 3 and 2 fold respectively (*P < 0.05). (B) Over expression of NFAT1 in SB-2 melanoma cells (non-metastatic, NFAT1 negative) induces autotaxin expression (*P < 0.05). (C) Over expression of NFAT1 alone significantly increases the invasive phenotype of melanoma cells, (**P < 0.001). (D) NFAT1 silencing decreases NFAT1 protein levels in A375SM cells. This results in decreased levels of autotaxin protein expression within the supernatant. (E) Reduced levels of autotaxin results in decreased activity as observed in the autotaxin activity assay. A silver stain was performed with equal volumes of supernatant used for the autotaxin activity assay as a loading control.

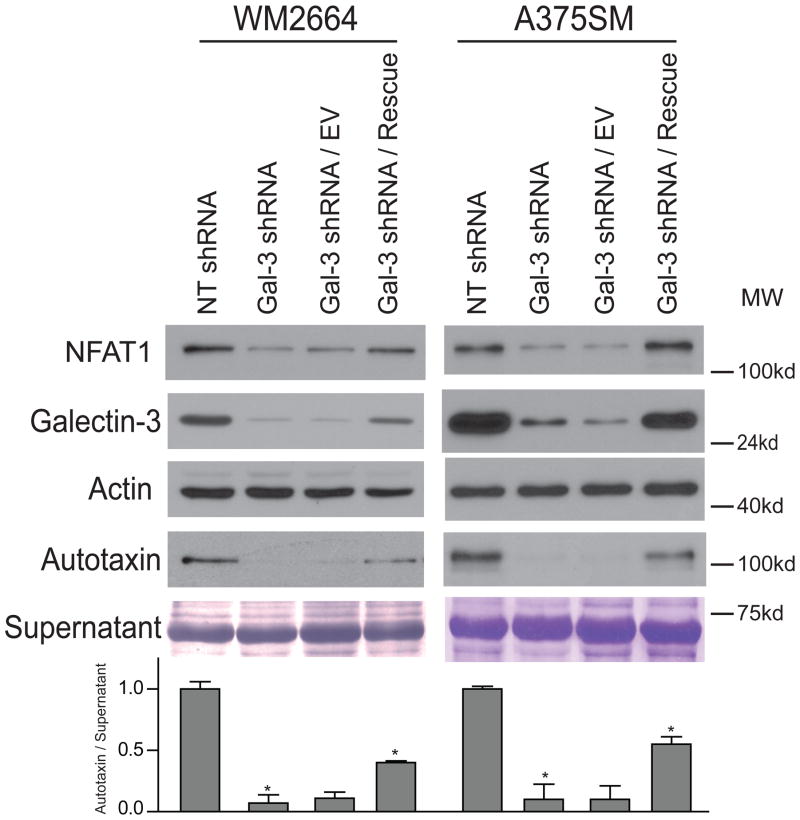

Rescue of Galectin-3 Reverts NFAT1 and Autotaxin Expression

Introducing small hairpin RNA has been reported to have nonspecific off-target effects. Therefore, galectin-3 was rescued in both melanoma cell lines to determine whether this can re-express NFAT1 and autotaxin expression. Indeed, after rescuing galectin-3 in both WM2664 and A375SM, both autotaxin and NFAT1 expression were reverted and rescued (Figure 4). This confirms that galectin-3 is indeed responsible for regulating NFAT1 and autotaxin protein expression.

Figure 4. Rescue of galectin-3 causes re-expression of autotaxin and NFAT1.

Rescue of galectin-3 reverts the expression of NFAT1 and autotaxin (*P < 0.05), thus, confirming that this is not an off target effect. A more efficient rescue of galectin-3 in A375SM melanoma cells shows a more dramatic re-expression of NFAT1 and autotaxin compared to less efficient rescue of WM2664 melanoma cells.

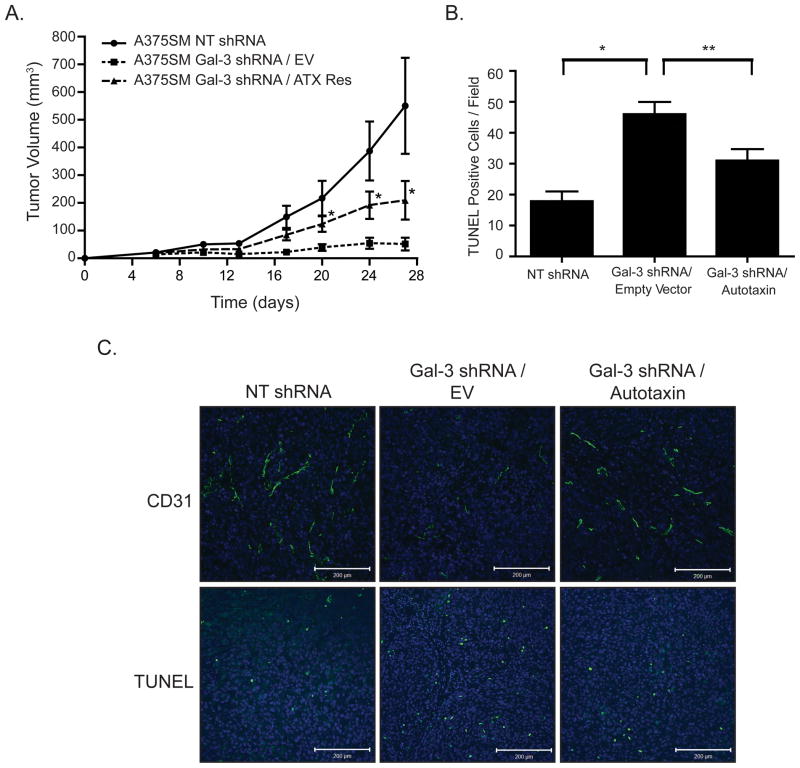

Re-expression of Autotaxin Partially Rescues Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis In Vivo

To correlate whether galectin-3 regulates melanoma progression in part by modulating autotaxin expression and activity, we stably re-expressed autotaxin in galectin-3 silenced melanoma cells and injected them subcutaneously in nude mice (Supplemental Figure S4). Re-expression of autotaxin partially rescues tumor growth as compared to galectin-3 shRNA melanoma cells transduced with an empty vector (p<0.05) (Figure 5A). Furthermore, silencing galectin-3 increases TUNEL positive cells within the tumor, indicating there is more cell death. Re-expression of autotaxin decreases the number of TUNEL positive cells (p<0.05) thus, indicating that autotaxin contributes to cell survival in vivo (Figure 5B and C). Mice injected with A375SM melanoma cells expressing the NT shRNA vector grew at a faster rate than those with autotaxin re-expression (Figure 5A). This suggests that galectin-3 regulates the expression of other genes and signaling pathways along with autotaxin to enhance tumor growth and cell survival as shown in our previous publication (16).

Figure 5. Regulation of Autotaxin by galectin-3 directly affects tumor growth, angiogenesis, and apoptosis.

(A) Induced expression of autotaxin with the stable lentiviral system partially rescues tumor growth as compared to an empty vector control in A375SM melanoma cells (*P < 0.05). (B) TUNEL analysis shows that silencing galectin-3 increases the number of TUNEL positive cells (*P < 0.01), and re-expression of autotaxin reduces the total number of apoptotic cells within the tumor (**P < 0.05). (C) The number of blood vessels, as indicated by CD31 staining, is also increased to comparable levels as NT shRNA with the rescue of autotaxin expression.

Previous studies have shown that galectin-3 can act as a pro-angiogenic molecule (15, 29). This same phenomenon occurs with autotaxin and LPA during development and cancer (30, 31). This could partially be due to decreased autotaxin expression. Indeed, silencing galectin-3 decreases the number of CD31 positive staining within the tumor, indicating there are fewer blood vessels (Figure 5C). Re-expression of autotaxin increases the amount of CD31 staining in tumors obtained from Figure 5A on day 27 suggesting that galectin-3 can regulate autotaxin expression and enhance angiogenesis in vivo (Figure 5C and Supplemental Figure S5). The increased number of blood vessels could be a contributing factor in which we see reduced TUNEL positive cells, and it is likely that our Gal-3/EV has increased apoptosis due to the lack of oxygen and nutrients within the tumor microenvironment. Our IHC staining confirmed that galectin-3 remained silenced on day 27 after tumor injections, and that autotaxin was rescued in these cells (Figure S3).

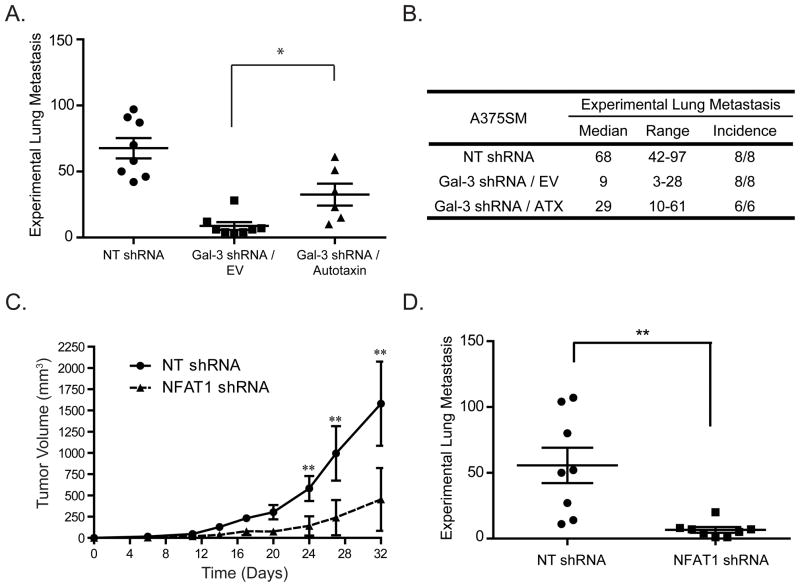

Galectin-3 Contributes to the Metastatic phenotype in part by regulating Autotaxin Expression

As autotaxin expression enhances migration and invasion in vitro (18, 32) and high levels of LPA or the over expression of autotaxin and LPA receptors induce metastasis in vivo (26, 33), we sought to determine whether the down regulation of autotaxin after silencing galectin-3 contributes to a reduced metastatic phenotype. When compared to NT shRNA A375SM, significantly fewer Gal-3 shRNA/EV A375SM cells metastasized to the lung with a median of 68 vs. 9 (p<0.05). When we re-express autotaxin there are significantly more metastatic lesions as compared to the empty vector with a median of 29 and 9 respectively (p<0.05) (Figure 6A and B). As in our subcutaneous model, we do not see a complete rescue of the metastatic potential after inducing autotaxin expression. Galectin-3 most likely regulates other genes, and performs other functions such as carbohydrate binding on cell surface glycoproteins during circulatory transport and extravasation into the lung parenchyma, or it can inhibit apoptosis to enhance cell survival. Taken together, our data show that the transcriptional regulation of autotaxin by galectin-3 contributes to melanoma growth and metastasis. However, autotaxin up regulation by galectin-3 is not the only mechanism in which galectin-3 contributes to metastasis, and galectin-3 enhances melanoma progression through additional mechanisms, such as the regulation of IL-8 and VE-cadherin as we previously demonstrated (16).

Figure 6. Galectin-3/NFAT1/Autotaxin axis contributes to the metastatic phenotype of A375SM melanoma cells.

(A) A graphical representation of the number of experimental lung metastasis formed after autotaxin is rescued in galectin-3 shRNA cells. The number is significantly increased as compared to empty vector transduced galectin-3 shRNA cells, *p<0.01. (B) A table representing the median and range of metastatic colonies on the lung surface along with the incidence of lung metastasis. (C) Tumor growth in A375SM cells decreases when silencing NFAT1 (**P < 0.001). (D) The number of experimental lung metastasis is significantly reduced after silencing NFAT1 in A375SM melanoma Cells (**P < 0.001).

It is also likely that NFAT1 regulates multiple genes that affect melanoma growth and metastasis. We therefore decided in the last set of experiments to intravenously and subcutaneously inject A375SM melanoma cells transduced with NT or NFAT1 shRNA. Silencing of NFAT1 also results in a significant inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis (Figure 6C and D). Taken together, our data supports the notion that NFAT1 plays a major role in melanoma growth and metastasis.

Discussion

We have previously shown that increased galectin-3 expression is correlated with the progression of melanoma in human patients, and its expression increases in highly metastatic cell lines (10, 16). Earlier reports from our lab identified that silencing galectin-3 decreases VE-Cadherin and IL-8 expression along with reducing tumor growth and experimental lung metastasis of C8161-c9 melanoma cells (16). In this study, we sought to identify whether galectin-3 expression can regulate previously unknown genes that are vital for melanoma growth and metastasis. By utilizing cDNA microarray profiling after silencing galectin-3 we identified autotaxin as a novel downstream target.

Our data represent a novel mechanism in which autotaxin is regulated by galectin-3. After silencing galectin-3 we observed reduced protein expression of the transcriptional regulator NFAT1. Indeed, the autotaxin promoter contains two NFAT1 binding sites within 300bp upstream from the transcription initiation site. Here we validate NFAT1 regulation of autotaxin by utilizing dual luciferase promoter analysis, NFAT1 siRNA, and NFAT1 over expression methods. Furthermore, we add another layer to this mechanism by confirming that galectin-3 expression in metastatic melanoma cell lines regulates NFAT1 protein expression.

NFAT1 exists within the cytoplasm in a highly phosphorylated, inactive state. Dephosphorylation is regulated by the phosphatase activity of the calcium-regulated protein calcineurin which induces nuclear localization and enhances transcriptional activity (34). NFAT1 kinases such as casein kinase 1 and GSK3B revert this process by phosphorylating and inactivating NFAT1 (34). However, conflicting data has been reported on GSK3B. Yoeli-Lerner et. al. reported that silencing GSK3B decreased the NFAT1 transcriptional activity. They also show that GSK3B shRNA decreased the protein expression of NFAT1 and its downstream target Cox-2 (35). In our system, we also observe decreased protein expression of NFAT1 after silencing galectin-3. Others have shown that galectin-3 can complex with and be phosphorylated by CK1 and GSK3B (7, 36). This implicates galectin-3, GSK3B, and NFAT1 within the WNT signaling pathway. In metastatic melanoma cells, galectin-3 expression could be required within this pathway to maintain NFAT1 protein expression.

Autotaxin is primarily secreted into the microenvironment where it performs its LysoPLD function. We report that silencing galectin-3 decreases autotaxin expression within the supernatant of melanoma cell lines, thus, supporting the notion that decreased autotaxin levels in the supernatant reduces the amount of cleaved FS-3. However, our FS-3 assay is semi quantitative since only FS-3 is used without the addition of LPC. FS-3 is then used as a substrate quickly and the rate of fluorescence is not linear. Furthermore, LPA can inhibit autotaxin in a negative feedback loop and NT shRNA cells produce more LPA within the media. This makes it difficult to directly correlate activity with expression in biological samples. Nonetheless, this assay demonstrates that the autotaxin activity levels correlate with the supernatant protein expression. LPA contributes to diverse physiological processes by activating multiple LPA receptors and induces various downstream signaling pathways via coupling to an array of G protein alpha subunits (37, 38). These molecular changes include PKC and NF-κB activation, RAS-MAPK signaling, activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kanses (PI3K), and activation of GTPases such as RAC and RhoA (39–41). LPA production leads to physiological processes such as cancer cell invasion, endothelial cell migration, and the up regulation of the chemokine IL-8 (16, 42–44).

Our lab has previously shown that silencing galectin-3 in melanoma cells significantly reduced tumor growth and metastasis of C8161 melanoma cells (16). This again is now demonstrated with our A375SM melanoma cell line. We also observed a significant reduction in the number of blood vessels within the tumor after silencing galectin-3. Others have also reported that galectin-3 acts as a pro-angiogenic molecule in breast cancer models (29). It is likely that one mechanism by which galectin-3 induces angiogenesis is through the regulation of autotaxin. In zebrafish autotaxin and its receptors are required for proper vascular development (45). Others have reported that autotaxin can enhance HUVEC migration in the presence of LPC along with inducing angiogenesis (31, 43). Silencing autotaxin expression in HUVECs significantly decreases LPA receptors and VEGFR2 expression (43). It has also been shown that VEGF can increase autotaxin expression and HIF1-α activation by LPA (43, 46). This implies that autotaxin and VEGF signaling can positively regulate each other during the angiogenic process. When we rescue autotaxin in our galectin-3 shRNA melanoma cells, we see a significant increase in blood vessels within the tumor. In our model it is likely that autotaxin expressed by the tumor cells enhances LPA production in the tumor microenvironment, which then acts upon endothelial cells to further increase the expression of LPA and VEGF receptors. This effect enhances endothelial cell migration and increases the number and size of tumor blood vessels. Recently, it has also been shown that autotaxin can regulate melanoma lymphangiogenesis by activating LPA receptors on lymphatic cells (47). Our melanoma cells also express LPA receptors in the EDG (Supplemental Figure S6A) and purinergic (Supplemental Figure S6B) family. As reviewed by Jankowski others have reported that autotaxin can induce melanoma cell motility by activating PI3Kγ and induce the expression of urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Furthermore, LPA can enhance migration through PAK1 phosphorylation and downstream FAK activation (48). These mechanisms result in increased melanoma motility. The production of LPA by autotaxin within the tumor microenvironment can potentially have a direct effect on tumor cells by activating signaling pathways that enhance tumor growth, inflammation, and cell survival. Re-expression of autotaxin partially rescues experimental lung metastasis after silencing galectin-3. Therefore, galectin-3 can regulate metastasis by multiple mechanisms directly, or indirectly through the regulation of autotaxin and the multiple genes and pathways that are deregulated by LPA.

To further establish a link between NFAT1 and melanoma growth and metastasis, we silenced NFAT1 in A375SM melanoma cells. We observed a decrease in tumor growth and the number of experimental lung metastasis after silencing NFAT1. As NFAT1 can potentially regulate multiple genes, further studies are needed to identify what genes NFAT1 regulates that affect tumor growth and metastasis. The genes identified after silencing galectin-3 then might be deregulated through the protein loss of NFAT1. Interestingly, others have reported that galectin-3 KO mice show reduced B16-F10 metastasis to the lung. This is reportedly due to decreased ability of the tumor cells to bind to and extravasate into the lung parenchyma (49). In addition, it has also been shown that NFAT1−/− mice have a reduced number of B16-F10 metastatic lesions (50). Along with our data, this implicates that both galectin-3 and NFAT1 play major roles in modulating the tumor microenvironment to support melanoma growth and metastasis.

Taken together, our data provide novel mechanism by which galectin-3 contributes to melanoma growth and metastasis via the regulation of the NFAT1/ATX/LPA pathway. This is likely to be one of many ways in which galectin-3 can promote melanoma progression. Our data only scratches the surface, as it is still unclear how galectin-3 affects NFAT1 protein expression. Yet, this is the first report to assign a mechanistic role for NFAT1 in melanoma progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Didier Trono (Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland) for providing the lentiviral backbone in which galectin-3 shRNA was inserted. This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH) Grant R01 CA76098, NIH Specialized Programs of Research Excellence in Skin Cancer Grant P50-CA093459 (to M.B.E), and NIH R37CA46120 (to A.R)

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Barondes SH, Cooper DN, Gitt MA, Leffler H. Galectins. Structure and function of a large family of animal lectins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20807–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gong HC, Honjo Y, Nangia-Makker P, Hogan V, Mazurak N, Bresalier RS, et al. The NH2 terminus of galectin-3 governs cellular compartmentalization and functions in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:6239–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazurek N, Sun YJ, Price JE, Ramdas L, Schober W, Nangia-Makker P, et al. Phosphorylation of galectin-3 contributes to malignant transformation of human epithelial cells via modulation of unique sets of genes. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10767–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ochieng J, Fridman R, Nangia-Makker P, Kleiner DE, Liotta LA, Stetler-Stevenson WG, et al. Galectin-3 is a novel substrate for human matrix metalloproteinases-2 and -9. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14109–14. doi: 10.1021/bi00251a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu F, Finley RL, Jr, Raz A, Kim HR. Galectin-3 translocates to the perinuclear membranes and inhibits cytochrome c release from the mitochondria. A role for synexin in galectin-3 translocation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15819–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200154200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elad-Sfadia G, Haklai R, Balan E, Kloog Y. Galectin-3 augments K-Ras activation and triggers a Ras signal that attenuates ERK but not phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34922–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimura T, Takenaka Y, Fukumori T, Tsutsumi S, Okada K, Hogan V, et al. Implication of galectin-3 in Wnt signaling. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3535–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dagher SF, Wang JL, Patterson RJ. Identification of galectin-3 as a factor in pre-mRNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1213–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Mercier M, Fortin S, Mathieu V, Kiss R, Lefranc F. Galectins and gliomas. Brain Pathol. 2009;20:17–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prieto VG, Mourad-Zeidan AA, Melnikova V, Johnson MM, Lopez A, Diwan AH, et al. Galectin-3 expression is associated with tumor progression and pattern of sun exposure in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6709–15. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu XC, el-Naggar AK, Lotan R. Differential expression of galectin-1 and galectin-3 in thyroid tumors. Potential diagnostic implications. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:815–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayashi T, Shimura T, Yajima T, Kubo N, Araki K, Tsutsumi S, et al. Transient gene silencing of galectin-3 suppresses pancreatic cancer cell migration and invasion through degradation of beta-catenin. Int J Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ijc.25946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honjo Y, Nangia-Makker P, Inohara H, Raz A. Down-regulation of galectin-3 suppresses tumorigenicity of human breast carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:661–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takenaka Y, Fukumori T, Yoshii T, Oka N, Inohara H, Kim HR, et al. Nuclear export of phosphorylated galectin-3 regulates its antiapoptotic activity in response to chemotherapeutic drugs. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4395–406. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4395-4406.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nangia-Makker P, Honjo Y, Sarvis R, Akahani S, Hogan V, Pienta KJ, et al. Galectin-3 induces endothelial cell morphogenesis and angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:899–909. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64959-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mourad-Zeidan AA, Melnikova VO, Wang H, Raz A, Bar-Eli M. Expression profiling of Galectin-3-depleted melanoma cells reveals its major role in melanoma cell plasticity and vasculogenic mimicry. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1839–52. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nangia-Makker P, Hogan V, Honjo Y, Baccarini S, Tait L, Bresalier R, et al. Inhibition of human cancer cell growth and metastasis in nude mice by oral intake of modified citrus pectin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1854–62. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.24.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stracke ML, Krutzsch HC, Unsworth EJ, Arestad A, Cioce V, Schiffmann E, et al. Identification, purification, and partial sequence analysis of autotaxin, a novel motility-stimulating protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2524–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee HY, Clair T, Mulvaney PT, Woodhouse EC, Aznavoorian S, Liotta LA, et al. Stimulation of tumor cell motility linked to phosphodiesterase catalytic site of autotaxin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24408–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umezu-Goto M, Kishi Y, Taira A, Hama K, Dohmae N, Takio K, et al. Autotaxin has lysophospholipase D activity leading to tumor cell growth and motility by lysophosphatidic acid production. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:227–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.An S, Bleu T, Zheng Y, Goetzl EJ. Recombinant human G protein-coupled lysophosphatidic acid receptors mediate intracellular calcium mobilization. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:881–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.5.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park SY, Jeong KJ, Panupinthu N, Yu S, Lee J, Han JW, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid augments human hepatocellular carcinoma cell invasion through LPA1 receptor and MMP-9 expression. Oncogene. 2010;30:1351–9. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanagida K, Ishii S. Non-Edg family LPA receptors: the cutting edge of LPA research. J Biochem. 2011;150:223–32. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobroff AS, Wang H, Melnikova VO, Villares GJ, Zigler M, Huang L, et al. Silencing cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) identifies CYR61 as a tumor suppressor gene in melanoma. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26194–206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris AJ, Smyth SS. Measurement of autotaxin/lysophospholipase D activity. Methods Enzymol. 2007;434:89–104. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)34005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu S, Umezu-Goto M, Murph M, Lu Y, Liu W, Zhang F, et al. Expression of autotaxin and lysophosphatidic acid receptors increases mammary tumorigenesis, invasion, and metastases. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:539–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferguson CG, Bigman CS, Richardson RD, van Meeteren LA, Moolenaar WH, Prestwich GD. Fluorogenic phospholipid substrate to detect lysophospholipase D/autotaxin activity. Org Lett. 2006;8:2023–6. doi: 10.1021/ol060414i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen M, O’Connor KL. Integrin alpha6beta4 promotes expression of autotaxin/ENPP2 autocrine motility factor in breast carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:5125–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nangia-Makker P, Wang Y, Raz T, Tait L, Balan V, Hogan V, et al. Cleavage of galectin-3 by matrix metalloproteases induces angiogenesis in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2530–41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Meeteren LA, Ruurs P, Stortelers C, Bouwman P, van Rooijen MA, Pradere JP, et al. Autotaxin, a secreted lysophospholipase D, is essential for blood vessel formation during development. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5015–22. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02419-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nam SW, Clair T, Kim YS, McMarlin A, Schiffmann E, Liotta LA, et al. Autotaxin (NPP-2), a metastasis-enhancing motogen, is an angiogenic factor. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6938–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaetano CG, Samadi N, Tomsig JL, Macdonald TL, Lynch KR, Brindley DN. Inhibition of autotaxin production or activity blocks lysophosphatidylcholine-induced migration of human breast cancer and melanoma cells. Mol Carcinog. 2009;48:801–9. doi: 10.1002/mc.20524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.David M, Wannecq E, Descotes F, Jansen S, Deux B, Ribeiro J, et al. Cancer cell expression of autotaxin controls bone metastasis formation in mouse through lysophosphatidic acid-dependent activation of osteoclasts. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okamura H, Aramburu J, Garcia-Rodriguez C, Viola JP, Raghavan A, Tahiliani M, et al. Concerted dephosphorylation of the transcription factor NFAT1 induces a conformational switch that regulates transcriptional activity. Mol Cell. 2000;6:539–50. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoeli-Lerner M, Chin YR, Hansen CK, Toker A. Akt/protein kinase b and glycogen synthase kinase-3beta signaling pathway regulates cell migration through the NFAT1 transcription factor. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:425–32. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huflejt ME, Turck CW, Lindstedt R, Barondes SH, Leffler H. L-29, a soluble lactose-binding lectin, is phosphorylated on serine 6 and serine 12 in vivo and by casein kinase I. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26712–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teo ST, Yung YC, Herr DR, Chun J. Lysophosphatidic acid in vascular development and disease. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:791–9. doi: 10.1002/iub.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mutoh T, Chun J. Lysophospholipid activation of G protein-coupled receptors. Subcell Biochem. 2008;49:269–97. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8831-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kranenburg O, Moolenaar WH. Ras-MAP kinase signaling by lysophosphatidic acid and other G protein-coupled receptor agonists. Oncogene. 2001;20:1540–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Leeuwen FN, Olivo C, Grivell S, Giepmans BN, Collard JG, Moolenaar WH. Rac activation by lysophosphatidic acid LPA1 receptors through the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Tiam1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:400–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210151200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hwang YS, Hodge JC, Sivapurapu N, Lindholm PF. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates PC-3 prostate cancer cell Matrigel invasion through activation of RhoA and NF-kappaB activity. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45:518–29. doi: 10.1002/mc.20183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li TT, Alemayehu M, Aziziyeh AI, Pape C, Pampillo M, Postovit LM, et al. Beta-arrestin/Ral signaling regulates lysophosphatidic acid-mediated migration and invasion of human breast tumor cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1064–77. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ptaszynska MM, Pendrak ML, Stracke ML, Roberts DD. Autotaxin signaling via lysophosphatidic acid receptors contributes to vascular endothelial growth factor-induced endothelial cell migration. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:309–21. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalari S, Zhao Y, Spannhake EW, Berdyshev EV, Natarajan V. Role of acylglycerol kinase in LPA-induced IL-8 secretion and transactivation of epidermal growth factor-receptor in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L328–36. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90431.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yukiura H, Hama K, Nakanaga K, Tanaka M, Asaoka Y, Okudaira S, et al. Autotaxin Regulates Vascular Development via Multiple Lysophosphatidic Acid (LPA) Receptors in Zebrafish. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:43972–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.301093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ptaszynska MM, Pendrak ML, Bandle RW, Stracke ML, Roberts DD. Positive feedback between vascular endothelial growth factor-A and autotaxin in ovarian cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:352–63. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mu H, Calderone TL, Davies MA, Prieto VG, Wang H, Mills GB, et al. Lysophosphatidic Acid induces lymphangiogenesis and IL-8 production in vitro in human lymphatic endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:2170–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jankowski M. Autotaxin: its role in biology of melanoma cells and as a pharmacological target. Enzyme Res. 2011;2011:194857. doi: 10.4061/2011/194857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Radosavljevic G, Jovanovic I, Majstorovic I, Mitrovic M, Lisnic VJ, Arsenijevic N, et al. Deletion of galectin-3 in the host attenuates metastasis of murine melanoma by modulating tumor adhesion and NK cell activity. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2011;28:451–62. doi: 10.1007/s10585-011-9383-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Werneck MB, Vieira-de-Abreu A, Chammas R, Viola JP. NFAT1 transcription factor is central in the regulation of tissue microenvironment for tumor metastasis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:537–46. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0964-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.