Abstract

Sexual identity development is a central task of adolescence and young adulthood and can be especially challenging for sexual minority youth. Recent research has moved from a stage model of identity development in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth to examining identity in a non-linear, multidimensional manner. In addition, although families have been identified as important to youth's identity development, limited research has examined the influence of parental responses to youth's disclosure of their LGB sexual orientation on LGB identity. The current study examined a multidimensional model of LGB identity and its links with parental support and rejection. One hundred and sixty-nine LGB adolescents and young adults (ages 14–24, 56% male, 48% gay, 31% lesbian, 21% bisexual) described themselves on dimensions of LGB identity and reported on parental rejection, sexuality-specific social support, and non-sexuality-specific social support. Using latent profile analysis (LPA), two profiles were identified, indicating that youth experience both affirmed and struggling identities. Results indicated that parental rejection and sexuality-specific social support from families were salient links to LGB identity profile classification, while non-sexuality specific social support was unrelated. Parental rejection and sexuality-specific social support may be important to target in interventions for families to foster affirmed LGB identity development in youth.

Keywords: Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Sexual Minority, Parental Rejection, Social Support

Developing a sense of identity is a central task of adolescence and young adulthood (Meeus, 2011). Although well studied among heterosexual youth, it is only in the past couple of decades that there has been a growing interest in understanding psychosocial development, in general, and identity development, in particular, among sexual minority youth. Although progress is being made in our understanding of the critical elements of identity for lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth, less well understood are the factors that influence identity development. Few would dispute the importance of the family context for youth development, but as yet, little is known about how parental behavior relates to identity development for LGB youth. The current study uses latent profile analysis to better understand how dimensions of identity group together and examines parental rejection and parental support as statistical predictors of these identity clusters.

LGB Identity

Sexual identity development is conceptualized as the process by which a person comes to recognize his or her sexual attractions and incorporates this awareness into his or her self-identity (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000). While all individuals engage in the process of sexual identity development, typically in adolescence and young adulthood (Worthington, Navarro, Savoy, & Hampton, 2008), LGB youth are presented with a unique set of challenges during this process. In particular, LGB youth may find the development of a positive sexual identity challenging in the face of social stigma and marginalization (Mohr & Kendra, 2011).

Although not well-understood in LGB populations (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2011), the broader identity literature (i.e. adolescent identity, ethnic identity, etc.) suggests that identity processes have important implications for youth outcomes; and stagnated identity development is associated with poorer adjustment (Archer & Grey, 2009; Marcia, 1966). Preliminary empirical evidence among LGB individuals supports this claim. Aspects of identity integration, defined as the process by which individuals increase commitment to their new LGB identity and further incorporate it into their sense of self, are linked to psychological adjustment for LGB youth (Morris, 1997; Rosario, Hunter, Maguen, Gwadz, & Smith, 2001; Rosario et al., 2011). Facets of LGB identity, including more positive attitudes towards homosexuality (Balsam & Mohr, 2007), greater outness (D'Augelli, 2002), and increased involvement in the LGB community (Morris, Waldo, & Rothblum, 2001), are linked to better adjustment (i.e., Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010).

With the establishment of identity as important to functioning, several theoretical approaches have been applied to understanding LGB identity. Although LGB identity development was historically thought of as a series of stages (Cass, 1979; Marcia, 1966; Troiden, 1988), recent work suggests that a hierarchical, linear stage model may not best characterize LGB identity development (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2008). Evidence indicates that not all LGB youth experience the same aspects of identity formation in the same way, at the same time, and some of the hypothesized stages (such as identity pride, which connotes a feeling of superiority over heterosexuals) may not be experienced at all. As such, researchers have shifted to conceptualizing identity development as a multidimensional, non-linear process (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000) in which there may be multiple trajectories and components to healthy identity formation. With the move toward a multidimensional framework has come the issue of understanding what variables constitute LGB identity (Mohr & Kendra, 2011). A preponderance of the research in this area has assessed identity through the single dimension of internalized homophobia (Mohr & Kendra, 2011). Internalized homophobia is the application of anti-LGB stigma to the self, though in recent years, it has been redefined as internalized homonegativity in order to distinguish internalized negative feelings and perceptions from internalized fear (Herek, 1994). While internalized homonegativity is critically important to include, it is also likely an overly restricted measure of identity.

Although support is growing for a multi-dimensional approach to understanding sexual identity, there is not always uniformity across studies in what dimensions constitute “identity.” One of the more comprehensive models, however, was developed by Mohr and Fassinger (2000) and later revised by Mohr and Kendra (2011). These authors identify six dimensions of identity development, including internalized homonegativity (rejection of one's LGB identity), concealment motivation (concern with and motivation to protect one' privacy as LGB person), acceptance concerns (concern with the potential for stigmatization as an LGB person), identity uncertainty (uncertainty about one's sexual orientation identity), identity superiority (view favoring LGB people over heterosexual people), and finding the experience of developing an LGB identity to be a difficult process. This multi-dimensional approach supports a well-rounded and thorough understanding of LGB identity.

Several recent studies highlight the range and diversity of identity development for LGB youth. Floyd and Stein (2002) identified five developmental trajectories that included aspects of identity and varied in terms of age of coming out, timing of milestones, parental attitudes, comfort with sexual orientation, and emotional distress. Rosario and colleagues (2008) also identified different patterns of sexual identity development and grouped LGB adolescents into high, middling, and low levels of identity integration. The groups differed in terms of high, moderate, and low levels of social support from others, gay-related stress, attitudes toward sexual minorities, and comfort with same sex attractions. Willoughby, Doty & Malik (2010) assessed multiple dimensions of LGB identity using Mohr's model (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000), but the dimensions were averaged, thus precluding the ability to examine any individual differences. Although expert panels recommend the inclusion of more than one dimension of sexual orientation identity in measurement (LGB Youth Sexual Orientation Measurement Work Group, 2003; Badgett, 2009), the above multivariate studies tend to be the exception rather than the rule in the literature (Saewyc, 2011).

In addition to variability emanating from conceptual or methodological differences, identity development also has been found to vary across a number of demographic covariates, including gender, sexual orientation, age, and ethnicity. Although early research primarily relied only on gay males, as an increasing number of studies include females and bisexuals, important gender differences have been noted. For example, females have been found to be more likely to engage in identity-centered development, while males more commonly engage in sex-centered development (Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000). Research also indicates that females are more likely to identify as bisexual and to vacillate between identity labels (Diamond, 2007). Age also has been identified as a factor related to identity development, and several researchers have found younger age of disclosure to be related to greater comfort with sexual orientation (Floyd & Stein, 2002). Very limited data on identity development among ethnic minority LGB youth exist, although one of the few studies to examine ethnicity found no differences in most milestones, including age of first identification as LGB, first same-sex attraction, and first time having sex with someone of the same-sex, for Caucasian, African-American, and Hispanic/Latino groups (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2004). In the present study, we examine how gender, sexual orientation, age and ethnicity relate to identity profiles.

One of the main goals of the present study is to assess and understand LGB identity in a novel, non-linear, multi-dimensional manner. Based on past literature suggesting that LGB identity is composed of numerous elements (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000; Mohr & Kendra, 2011; Rosario et al., 2008), including internalized homonegativity, concealment motivation, acceptance concerns, identity uncertainty, and difficult process, we examined patterns of response across these dimensions using latent profile analysis (LPA). Typically, dimensions of LGB identity have been examined using a variable-centered approach, such as regression. Although commonly used, a limitation of this technique is that it assumes that the effect of a particular dimension operates independent of other dimensions, providing no information about how levels of multiple dimensions naturally cluster within a population. As LPA allows for variability and interrelationships among dimensions, we sought to understand whether youth were uniformly high or low on all dimensions, or whether they exhibited diverse responses across dimensions.

Family Influences on LGB Identity

In the past decade, there has been increased interest in trying to understand what factors affect LGB identity. Symbolic interaction theory, a classical theory of identity development (Cooley, 1902; Mead, 1934), argues that individuals conceive a sense of identity through their interactions with others. Specifically, self-perceptions are highly influenced by the way that individuals perceive others to view them, such that if one feels disliked by others, that individual is more likely to feel more negatively about oneself. Empirical evidence supports this theory among adolescent samples more generally. For example, Berenson, Crawford, Cohen, & Brook (2005) and Robertson & Simons (1989) both found that adolescents and young adults who experience parental rejection have lower self-esteem. Furthermore, adolescents who perceive support from parents have been found to have increased global self-worth (Robinson, 1995). Taken together, symbolic interaction theory and empirical studies of parenting suggest that parental responses will significantly influence sexual minority identity development in adolescents and young adults.

Parental responses to youth's sexual minority status have been found to vary widely (Beeler & DiProva, 1999; D'Augelli, Hershberger, & Pilkington, 1998; Floyd, Stein, Harter, Allison, & Nye, 1999). Though data are limited with families of LGB adolescents, parental rejection and parental support both appear to be important factors to consider in understanding LGB youth functioning. Parental rejection focuses specifically on negative reactions from parents in regard to youth LGB status, and functions not as the direct inverse of acceptance (i.e., low parental rejection does not guarantee high parental acceptance), but as a distinct, although highly related, dimension. Parental rejection of youth's sexuality is considered one of the most important problems facing gay and lesbian youth (D'Augelli & Hershberger, 1993; Savin-Williams, 1989). Caitlin Ryan and her colleagues have established an important line of research that documents the importance of both parental rejection (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009) and parental support (Ryan, Russell, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2010) as predictors of a variety of mental health and physical health outcomes in LGB youth. For example, family rejection was found to be associated with an increased likelihood of having depression, suicidal ideation, illicit substance use, and unprotected sex with casual partners (Ryan et al., 2009).

In addition to studies focusing on general mental and physical health outcomes, preliminary evidence also shows that parental rejection and other family reactions are linked to LGB identity development (i.e. Savin-Williams, 1989). In a sample of 317 gay and lesbian youth aged 14–23 years, Savin-Williams (1989) found that youths' perceptions of relatively positive parental attitudes regarding sexual orientation were associated with personal comfort with orientation, increased self-esteem for the youths, and fewer self-critical behaviors. In a study of 72 LGB youth ages 16–27, parental acceptance of and attitudes toward their child's same sex attractions were linked to a greater consolidation of a sexual orientation identity in youth, which was defined as more openness and comfort with sexual orientation (Floyd et al., 1999). A third study of 81 LGB youth ages 14–25 found that family rejection of sexual orientation is related to negative LGB identity, operationalized by a summary score across six dimensions, including internalizing homonegativity, identity confusion, and need for acceptance (Willoughby et al., 2010). These studies, although few in number, provide consistent support for a relationship between parental rejection and LGB identity.

Social support from parents is another important factor with regard to family response to youth sexuality. In general, support within one's family of origin, and particularly support from parents, is proposed to play a critical role in the development of a person's internal sense of support (Branje, van Aken, & van Lieshout, 2002). Specific to sexual minority youth, it has been suggested that a supportive social context may promote sexual identity development (Mohr & Fassinger, 2003; Rosario et al., 2008), though only one empirical study was found in this area. In a study of 146 LGB youth, Rosario and colleagues (2008) found that family social support facilitated optimal identity development. Yet, this study assessed general family social support, and new research indicates that sexuality-specific social support may be more salient for LGB youth (Doty, Willoughby, Lindahl, & Malik, 2010). Thus, the current study aims to understand how sexuality-specific and non-sexuality-specific social support are distinctively related to LGB identity.

While the above studies offer important first steps towards understanding the ways that parental responses influence youth sexual identity, these findings are qualified by several areas of omission. First, most studies operationalize identity with a single variable. As previously discussed, sexual identity may be best characterized by many different dimensions (i.e. Mohr & Fassinger, 2000). Therefore, limiting the assessment of identity to comfort and openness about sexual orientation or internalized homonegativity, as a majority of studies have done, may not portray the full spectrum of identity. Second, time since youth disclosed their sexual minority status to their parents is rarely studied. As preliminary studies consistently suggest that parental responses fluctuate considerably over time following disclosure (Beals & Peplau, 2006; Beeler & DiProva, 1999), it is critical to consider how much time has passed and to account statistically for the length of time if it varies across participants. Third, little is known about how parental responses relate to identity development in adolescent and young adult LGB youth. Further research should address these areas of omission to more accurately establish how parental responses are linked to youth LGB identity.

Study Aims and Hypotheses

The present study has three principle aims. The first aim of the study is to use LPA to identify identity profiles, or patterns of response across multiple dimensions of LGB identity. We hypothesized that some youth patterns would be characterized by identity struggles, while other youth would portray an affirmed or positive identity. We were particularly interested in the pattern of relationships among dimensions, and expected to find different levels of each dimension within each profile, such that youth within the affirmed identity profile, for instance, might show especially low levels of internalized homonegativity, yet moderate levels of concealment motivation.

The second aim of the study was to understand the role of demographic and contextual covariates in sexual minority identity. As previous research identified differences in development across gender, sexual orientation, and age (Diamond, 2007; Floyd & Stein, 2002; Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000), these factors were expected to be related to LGB identity in the present study. Specifically, females and older youth were expected to be more likely to show affirmed LGB identity, and bisexual youth were expected to engage in more identity struggles. Given the dearth of information regarding LGB ethnic minority youth, ethnic differences in identity profiles were examined, though differences were not expected, in keeping with findings from Rosario, Schrimshaw & Hunter (2004). Time since disclosure, an often critically overlooked variable in previous research, also was examined as a covariate.

The third aim of the study was to examine links between parental rejection and support with youth sexual identity. As preliminary research has linked parental rejection and LGB identity (Floyd et al., 1999; Willoughby et al., 2010; Savin-Williams, 1989), we expected parental rejection to be related to less positive LGB identity. Based on limited research suggesting that social support is important for LGB identity (Mohr & Fassinger, 2003; Rosario et al., 2008), and a single study showing that sexuality specific-social support is most salient for LGB youth (Doty et al., 2010), we also hypothesized that sexuality-specific social support would be related to more positive LGB identity, while general non-sexuality-specific social support would be unrelated.

Methods

Participants

One hundred and sixty-nine LGB adolescents and young adults participated in the current study. Youth ranged in age from 14 to 24. Fifty-six percent of the youth sample was male. Self-identified sexual orientations of participants included gay (48%), lesbian (31%), and bisexual (21%). Of those who identified as bisexual, 36% were male and 64% were female. Participants represented a diverse range of ethnicities, including White: Non-Hispanic (40%), White: Hispanic (38%), and Black (including African American and Caribbean American) (22%), reflecting the surrounding community. Years of education for the youth ranged from completing 7th grade to completing graduate school. Time since first disclosure to a parent ranged from 0 to 11 years (M = 3.05, SD = 2.49). For those youth who were “out” to a parent, the average age, in years, at initial disclosure to a parent was 16.23 (SD = 2.67).

Procedure

IRB approval of the study was secured. As part of a larger longitudinal study on the peer and family relationships of LGB young people, participants were recruited via fliers in the community, websites, and community organizations. Interested participants were instructed to contact research staff by phone or e-mail. All questionnaires included in the current study were from the initial assessment of the longitudinal study. Only the procedures relevant to the current study are described here. Youth under 18 were required to get parental consent in order to participate, and therefore all youth under 18 who participated were out to at least one parent. Consent was obtained for youth over 18. All participants completing the study protocol were offered four free counseling sessions with clinically trained project staff, as incentive for participation as well as to aid with human subject issues. Youth were compensated $50 for study participation.

Measures

Demographic information

To collect relevant demographic information, participants were asked to complete a background information questionnaire. This questionnaire assessed age, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and time since youth disclosed sexual minority status to a parent.

LGB identity

LGB identity difficulty was assessed using six subscales from the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale (LGBIS; Mohr & Fassinger, 2000). The LGBIS consists of twenty-seven items using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“disagree strongly”) to 7 (“agree strongly”), and subscales scores are computed by taking the mean of the items. The present study uses five of the six LGBIS subscales: Internalized Homonegativity/Binegativity (five items), Concealment Motivation (six items), Acceptance Concerns (five items), Identity Uncertainty (four items), and Difficult Process (five items). The Feelings of Superiority subscale was omitted due to inadequate psychometric properties, specifically poor internal consistency, similar to Mohr and Kendra (2011). Initial evidence of satisfactory reliability and validity has been established for the LGIS (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000), which was later adapted for use with bisexual individuals and renamed the LGBIS. There were no missing data on any of the LGBIS scales. The five LGBIS scales used in this study are described in further detail below.

Internalized Homonegativity/Binegativity

The Internalized Homonegativity/Binegativity Scale assesses the degree of negativity the participant associates with their sexual minority identity. The scale also measures to what extent one favors heterosexuality over LGB sexual orientations. Items include “I would rather be straight if I could” and “Homosexual lifestyles are not as fulfilling as heterosexual lifestyles.” Adequate internal consistency was found in the current study (α = .66) and in prior research (α = .79; Mohr & Fassinger, 2000).

Concealment Motivation

The Concealment Motivation scale measures how much the participant prefers to keep their same-sex romantic relationships private, and to what degree the participant fears a lack of control over disclosure of their sexual orientation. Items include “I prefer to keep my same-sex romantic relationships rather private” and “My private sexual behavior is nobody's business.” Good internal consistency was found in the current study (α = .75) and in prior research (α = .81; Mohr & Fassinger, 2000).

Acceptance Concerns

The Acceptance Concerns scale assesses how much the participant feels insecure around straight people, and how worried the participant feels with others' views of their sexual orientation. Items include “I often wonder whether others judge me for my sexual orientation” and “I can't feel comfortable knowing that others judge me negatively for my sexual orientation.” The current study (α = .78) and prior research (α = .75; Mohr & Fassinger, 2000) established good internal consistency of this scale.

Identity Uncertainty

The Identity Uncertainty scale measures how certain the participant is about his or her own sexual orientation. Items include “I'm not totally sure what my sexual orientation is” and “I keep changing my mind about my sexual orientation.” The current study (α = .83) and prior research (α = .77; Mohr & Fassinger, 2000) established good internal consistency of this scale.

Difficult Process

The Difficult Process scale assesses how uncomfortable and challenging the process of sexual orientation development has been for the participant. Items include “Coming out to my friends and family has been a very lengthy process” and “Admitting to myself that I'm an LGB person has been a very painful process.” Good internal reliability was established in the current study (α = .76) and prior research (α = .79; Mohr & Fassinger, 2000).

Parental Rejection

The Perceived Parental Reactions Scale (PPRS) is a 32-item measure that assesses youth perceptions of parental response to their sexual orientation (Willoughby, Malik, & Lindahl, 2006). Items include “My parent supports me” and “My parent says I am no longer his/her child,” and positive stated items are reverse scored. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale indicating degree of agreement with the item. Higher total scores on the PPRS indicate more parental rejection. Scores on the PPRS ranged from 32 to 150 (M = 83.68, SD = 34.11). Adequate reliability has been demonstrated (α = 97; Willoughby et al., 2006) and was established in the current sample (α = .97). Participants who were not out of a parent (13%) did not complete the PPRS.

Family Social Support

A modified version of the Social Support Behaviors Scale (SSB) was used to measure the perceived availability of sexuality-specific and non-sexuality-specific social support (Doty et al., 2010; Vaux, Riedel, & Stewart, 1987), though none of the items refer to LGB sexual orientation specifically. The scale consisted of 44 items, half of which asked about family support for problems not related to sexuality and half of which asked about family support for problems related to sexuality. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, indicating the likelihood of their family providing various types of assistance (e.g. “would comfort me,” “try to cheer me up”). Good internal consistency has been demonstrated for both sexuality-specific and non-sexuality specific composites (α = .97–.98; Doty et al., 2010) and was established in the current sample (α = .98). There were no missing data on the SSB.

Analyses

Preliminary analyses were conducted to obtain descriptive data, examine correlations, and assess psychometric properties of the measures used. To test study hypotheses, LPA was used to investigate the number of classes underlying the multi-dimensional assessment of LGB identity. LPA is a person-centered, latent variable approach used to classify participants into optimal grouping categories, based on common endorsement of continuous identity dimensions. LPA allows identification of discrete latent variables based on the scores from two or more observed variables (McCutcheon, 1987), and uses these latent variables to characterize LGB youth by a pattern of complex identity attributes.

All analyses were conducted using Mplus 6.0 software (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). The first set of analyses identified LGB identity subgroups within the sample, with five identity dimensions as indicators, using LPA. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to identify the latent classes, under the assumption that the data are missing at random (Little, 1995), which is a commonly recommended way of handling missing data (Muthén & Shedden, 1999; Schafer & Graham, 2002). Multiple start values were provided to encourage a proper solution and avoid local maxima (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). LPA provides several fit indices to help assess the fit of various solutions to the data, including the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978, Sclove, 1987), entropy, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001), and the parametric bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (McLachlan, 1987). Lower AIC and BIC, higher entropy, and significant Lo-Mendel-Rubin and bootstrap likelihood ratio test values are indicative of better model fit (Henson, Reise, & Kim, 2007; Lo et al., 2001; McLachlan & Peel, 2000; Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007; Yang, 2006). As previous research warns against the sole use of goodness-of-fit indices to determine the ideal number of profiles, ease of interpretability, parsimony, and match to theory were also strongly considered in choosing a profile solution (Muthén, 2001; Muthén & Muthén, 2000; Vermunt & Magidson, 2002). Once a profile solution was selected, the second and third study hypotheses were examined by conducting latent class regressions to determine if demographic and parent response variables were associated with class membership.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means, standard deviations, frequencies, and zero-order correlations among all study variables are provided in Table 1. Mean levels of all identity dimensions fell within the low to moderate range, meaning that participants in this study, on average, did not experience high levels of identity problems, which was expected given that it was a community sample. Youth reported moderate levels of sexuality-specific social support from parents, but significantly higher levels of non-sexuality-specific social support, t (167) = −9.09, p < .001. Youth also reported moderate levels of parental rejection.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Between Study Variables (N = 169)

| Mean | SD | Frequency (%) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | - | - | - | ||||||||||

| (Hispanic/ | 38.1 | ||||||||||||

| Caucasian/ | 39.3 | ||||||||||||

| African-American) | 22.6 | ||||||||||||

| Sexual Orientation | - | - | |||||||||||

| (Gay/ | 47.6 | ||||||||||||

| Lesbian/ | 31.2 | ||||||||||||

| Bisexual) | 21.2 | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 1. Age | 19.46 | 2.60 | - | - | |||||||||

| 2. Time since Disclosure | 2.99 | 2.42 | - | 40*** | - | ||||||||

| 3. Gender (Male/Female) | - | - | 55.3/44.7 | −.05 | .08 | - | |||||||

| 4. Internalizing Homonegativity | 1.96 | 1.08 | - | −.00 | −.38 | −.27*** | - | ||||||

| 5. Concealment Motivation | 4.11 | 1.32 | - | .09 | −.21** | .01 | .26** | - | |||||

| 6.Acceptance Concerns | 2.88 | 1.34 | - | −.00 | −.19* | −.14 | .43*** | .56*** | - | ||||

| 7. Identity Uncertainty | 1.61 | 1.09 | - | −.09 | −.21** | .08 | .13 | .19* | .18* | - | |||

| 8. Difficult Process | 3.01 | 1.27 | - | −.01 | −.23** | −.20** | .53*** | .38*** | .54*** | .13 | - | ||

| 9. Parental Rejection | 66.61 | 31.20 | - | −.15 | −.13 | −.16 | .349*** | .13 | .22* | .02 | .29** | - | |

| 10. Sexuality-Specific Social Support | 69.89 | 26.56 | - | .13 | .14 | −.07 | −.22** | −.21** | −.11 | .01 | −.21** | −.56*** | - |

| 11. Non-Sexuality-Specific Social Support | 85.07 | 24.07 | - | .15 | .06 | −.06 | −.07 | −.15 | .00 | .02 | −.04 | −.38*** | .65*** |

p≤.05.

p≤.01.

p≤.001.

A series of MANOVAs were used to examine demographic group differences on the five LGBIS identity scales. The overall main effect of ethnicity was not significant, F (2, 165) = .64, p = .81, ns, indicating that Hispanic/Latino, White, non-Hispanic/Latino, and African-American participants reported similar levels of functioning across the five subscales of the LGBIS. However, the overall main effects of sexual orientation, F(2, 167) = 5.37, p < .001, and gender, F(1, 168) = 3.54, p < .01, were significant, indicating that gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth, and male and female youth, significantly differed on the measures of identity. Follow-up univariate analyses indicated that gay youth reported more internalized homonegativity than lesbian youth (p < .01), and bisexual youth reported more identity uncertainty than both gay and lesbian youth (ps < .001. Also, males reported greater identity difficulties than females (p < .01). Correlations between youth age and time since disclosure with identity dimensions were also examined. As seen in Table 1, youth age did not correlate significantly with any of the LGBIS identity scales, while time since disclosure was negatively correlated with identity difficulties on the following scales: concealment motivation, acceptance concerns, identity uncertainty, and difficult process. Sexual orientation, gender, and time since disclosure were retained as covariates in all future analyses. For sexual orientation, to aid in interpretability and avoid overlap with gender, a dummy code where gay/lesbian were coded as one group and bisexual as the other was used. Although not significantly related to identity dimensions, youth age was retained as a covariate based on prior research.

Latent Profile Analysis

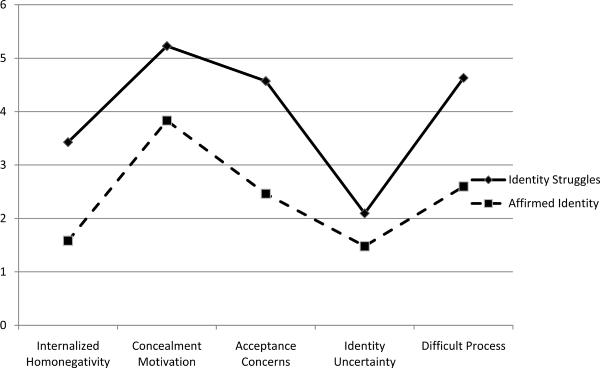

A LPA was conducted to determine the optimal number of classes of LGB identity and the dimensional characteristics associated with each class. Five indicators were included in these analyses: Internalized Homonegativity, Concealment Motivation, Acceptance Concerns, Identity Uncertainty, and Difficult Process. To determine the optimal solution, we iteratively estimated one- to four-profile solutions, which are summarized in Table 2. Fit indices, interpretability, and theoretical match were evaluated, and it was determined that the two-profile solution was optimal because of the better distribution of participants across classes, acceptable fit indices, and interpretability of the solution. Figure 1 presents the two patterns of identity identified through LPA, using LGBIS subscales (scales range from 1–7). The largest group (n = 135), labeled affirmed identity, displays minimal internalized homonegativity (M = 1.58), acceptance concerns (M = 2.44), identity uncertainty (M = 1.47), and difficult process (M = 2.59), and moderate levels of concealment motivation (M = 3.82). The smaller group (n = 35), labeled identity struggles, reported moderately low identity uncertainty (M = 2.10), moderate levels of internalized homonegativity (M = 3.40), and moderately high levels of concealment motivation (M = 5.21), acceptance concerns (M = 4.57), and difficult process (M = 4.61).

Table 2.

Fit Indices for Latent Profile Analyses on Sexual Identity Development

| Log-likelihood | No. Free Parameters | AIC | BIC | Adjusted LMR_LRT | BLRT | Entropy | Profile Sample Sizes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Profile | −1360.342 | 10 | 2740.685 | 2771.984 | - | - | - | 169 |

| 2 Profiles | −1268.721 | 16 | 2569.443 | 2619.521 | .0039 | <.0001 | .899 | 136/33 |

| 3 Profiles | −1231.691 | 22 | 2507.383 | 2576.241 | .2585 | <.0001 | .941 | 134/22/13 |

| 4 Profiles | −1189.983 | 28 | 2435.966 | 2523.603 | .5092 | −<.0001 | .961 | 118/24/16/11 |

Note. Fit indices for the final solution are in bold. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; LMR _LRT = Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test; BLRT = Bootstrap likelihood ratio test.

Figure 1.

Identity Characteristics of Affirmed Identity and Identity Struggles Profiles

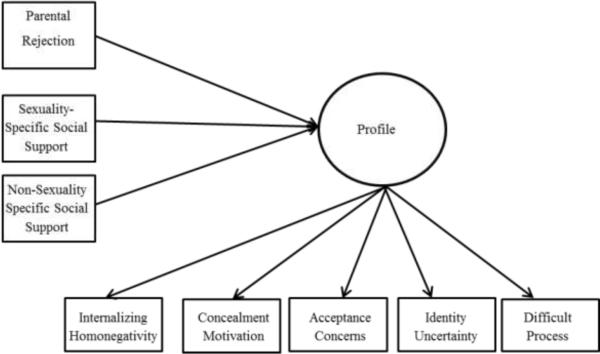

Predictors of Profile Membership

Based on prior literature and preliminary analyses, we hypothesized that several demographic and parental response variables would be associated with identity, and consequently, profile membership. Youth age, sexual orientation, gender, length of time since disclosure to a parent, parental rejection, non-sexuality-specific social support, and sexuality-specific social support were entered as predictors of profile membership to determine if these demographics or parental responses distinguished among the groups (see Figure 2). With regard to demographic covariates, time since disclosure was significantly related to profile membership, such that youth who had more recently disclosed their sexual orientation to a parent were more likely to be in the identity struggles profile. Youth age, sexual orientation, and gender were unrelated to profile membership.

Figure 2.

Path model of Parental Response Multivariate Predictors of Profile Comparisons

With regard to parental responses, results indicated that parental rejection and sexuality-specific social support were significantly related to profile membership, though gender was no longer significant. Less parental rejection and more sexuality-specific social support were associated with a greater likelihood of membership in the affirmed identity profile than the identity struggles profile (see Table 3). These findings suggest the salience of parental rejection, even after length of time since disclosure has been controlled for, and the importance of sexuality-specific social support, as opposed to general social support, on identity development.

Table 3.

Demographic/Contextual and Parental Response Multivariate Predictors of Profile Comparisons

| Affirmed Identity vs. Identity Struggles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | b | SE | z | OR |

| Demographic/Contextual + Parental Responses | ||||

| 1.Age | 0.29 | 0.15 | 1.93 | 1.34 |

| 2. Gender | −0.77 | 0.77 | −1.00 | 0.46 |

| 3. Sexual Orientation | 0.18 | 1.03 | 0.18 | 1.20 |

| 4. Time since Disclosure | −0.65** | 0.23 | −2.81 | 0.52 |

| 5. Parental Rejection | 0.03** | 0.01 | 2.81 | 1.03 |

| 6. Sexuality-Specific Social Support | 0.01* | 0.02 | 0.51 | 1.01 |

| 7. Non-Sexuality-Specific Social Support | −0.03 | 0.02 | −1.93 | 0.97 |

Note. OR = Odds Ratio.

p≤.05.

p≤.01.

Discussion

LGB youth form their sexual identity through the “coming out” process to themselves and others, and this process can be fraught with significant stress (Savin-Williams, 2001). There has been significant variability in the assessment of LGB identity development, although recent research suggests that non-linear, multidimensional measurement best characterizes the process, and that identity is impacted by parental reactions (Rosario et al., 2008; Saewyc, 2011). The current study is among the first to examine LGB identity in a person-centered, multidimensional manner, which allows for multiple patterns and individuality in identities. Most studies that create a single composite or use only a single dimension fail to capture the complexity of sexual identities in LGB youth. The LPA provides information about the patterns of identity within a person, such that a single person can be high on certain dimensions and low on others. The study also provides initial evidence for the link between parental rejection and support and LGB identity among adolescents and young adults.

Patterns of Sexual Minority Identity

Consistent with our first hypothesis, LGB identity was found to occur in one of two patterns. Most of the youth were classified in an affirmed identity pattern, while a smaller subset was classified in a pattern of identity struggles. Youth in the affirmed identity profile were characterized by lower levels of all five identity dimensions, as compared to the identity struggles profile, while variability across dimensions remained within each profile. Youth in the affirmed identity profile reported very low internalized homonegativity and identity uncertainty, suggesting that they feel confident in their identification as a LGB person and do not feel negatively about being a sexual minority. In addition, they reported low levels of difficulty coming out to friends and family and they had minimal concerns about being accepted by others because of their sexuality. Despite fairly low levels of difficulty across other dimensions of identity, in the affirmed identity profile, concealment motivations fell in the moderate range, suggesting that moderate levels of privacy needs occur in the same individuals who report especially low levels of internalized homonegativity, acceptance concerns, identity confusion, and difficulties with the coming out process. Needs for privacy are likely to be fairly normative in young adults (Margulis, 2003; Westin, 1976), and therefore these data may reflect a developmentally appropriate expectation for privacy about sexuality that may transcend sexual orientation.

The identity struggles profile indicates that some youth struggle with their LGB identity. In the identity struggles profile, identity confusion was relatively low, while all other areas were moderately high. This suggests that even when individuals experience other difficulties with regard to their LGB identity, they are fairly certain about their LGB status. While youth in this profile are, like the affirmed identity group, fairly certain of their sexual orientation, youth who fit the identity struggles profile also reported higher levels of internalized homonegativity, concerns about how well they are accepted as LGB people, and they indicated that the coming out process has been difficult for them. Finally, the identity struggles profile shows high levels of concealment motivation. While moderate levels of privacy can be considered normative, the very high endorsement of need for privacy in this group may reflect negative feelings and discomfort with their orientation, and perhaps a desire to stay “closeted” to avoid confronting these feelings or risking negative reactions from others.

The affirmed identity profile is the larger of the two profiles (n = 135 vs. n = 35), with means on the identity dimensions similar to the standardization sample (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000). These data are encouraging in that they suggest that the majority of LGB youth may be likely to experience affirmed identity. This is an important finding, as there is significant controversy regarding how “at risk” LGB youth are (Savin-Williams, 2001), and how vulnerable to maladjustment they may be in terms of identity, given the challenges that they face as sexual minority individuals. One of the important contributions of the LPA, however, is that it allowed for an understanding that not one but two profiles fit the data provided by the youth in the sample. The presence of a group classified as struggling with their identities provides empirical evidence that there may be legitimate concerns for a sizable minority LGB youth (21% in the present sample), as they come to terms with who they are. While most LGB youth may not be at risk for a negative sense of self, these data suggest that not all are immune to the difficulties that may exist. If the LGB identity dimensions were examined using a more traditional variable-centered approach, such as a path analysis, the intraindividual variability across dimensions could not be established. The identification of these patterns provides essential information about which levels are fairly normative within each profile. Furthermore, the use of profiles generated by LPA across multiple dimensions helps differentiate those individuals who may report similar levels on some dimensions (i.e. identity uncertainty), but drastically different levels on others (i.e. internalized homonegativity). In this study, both the affirmed and the struggling profile groups reported low identity uncertainty, but they differed substantially in terms of internalized homonegativity, acceptance concerns, concealment motivations, and how difficult the coming out process has been for them. Recognizing whether or not there is a group of LGB youth who are vulnerable to identity problems, and what might constitute areas of identity particularly at risk, was one of the major goals of the current study.

Multiple factors may contribute to variability in LGB identity development. Our second hypothesis related to demographic variables, examining gender, sexual orientation, age, time since coming out, and ethnicity as possible predictors of sexual identity. Only time since disclosure remained important in predicting identity classification, such that youth who had more recently disclosed their sexual orientation to a parent were more likely to be classified into the identity struggles profile. It is also of note that despite a moderate correlation with age, only time since disclosure was a significant demographic covariate with the LGB identity profiles. No matter the age of an individual, the length of time that he or she has been out to a parent plays a more salient role with regard to their LGB identity. This is particularly important information for interventionists to keep in mind when providing services for LGB youth, as they may need to focus treatment more on family responses early after disclosure, and less after time passes.

The Impact of Family Responses on Identity Patterns

Data supported the third hypothesis that family responses are related to LGB identity profile membership. Parental rejection and sexuality-specific social support were both associated with affirmed profile membership. Consistent with prior research (Doty et al., 2010), non-sexuality-specific social support was unrelated to profile membership. Even though adolescence and young adulthood are distinguished by increasing autonomy from parents (Arnett, 2000), study findings indicate that parental acceptance and sexuality-specific support remain critical protective resources for LGB youth in these developmental stages. Furthermore, results suggest that even if families provide non-sexuality-specific support, sexuality related identity struggles and high parental rejection remain linked to LGB identity. By identifying parental rejection and sexuality-specific social support as the more salient family influences of LGB identity, interventions can directly target these factors, instead of broadly targeting parental support in general. Working with families of sexual minority youth may help guide family members to become skilled at providing appropriate and useful support to their child, which may promote positive identity development for youth. Limited interventions exist that are informed by science for families with LGB youth. Data such as these in the present study can be used to inform and increase specificity of family interventions, which will likely result in increased benefit for both LGB youth and their families alike. Importantly, these dimensions of the family support system were linked with identity processes, even after controlling for time since disclosure. Thus, while LGB sense of identity does seem to improve with time (though only longitudinal data can truly demonstrate this), parental responses still matter.

Limitations and Future Directions

While this study offers a clear contribution to the literature on LGB identity in LGB young people, it remains subject to several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of this study limits interpretation of the directionality of links between family processes and LGB identity. Prior research (Rosario et al., 2008) with a prospective sample of youth found that family support was an important predictor of positive aspects of LGB identity over time, consistent with study findings. Additional research with longitudinal designs will be important to evaluate the relationship between family processes (including parental acceptance or rejection and sexuality specific social support, among other variables) with LGB identity development over time. Such studies will be able to identify both the order of effects and the degree of consistency and change in sexual identity development.

Another important limitation relates to the generalizability of study findings. Attempts were made in the current study to diversify the sample with multiple recruitment strategies. Nevertheless, the majority of participants, similar to other studies, were recruited through community organizations that serve sexual minority youth. Participants of such organizations may not represent the larger LGB population who are not involved in community or university-based organizations (Meyer & Colten, 1999). Furthermore, participants only were included in the study if they identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. Therefore, sexual minority individuals who do not identify with LGB labels, but do experience same-sex attractions, may not be represented by the study sample. Additionally, youth under 18 were required to obtain parental consent and consequently were required to be out to at least one parent; in fact, the majority of study participants were out to a parent. These participants may not be representative of youth who are not out to a parent. In particular, one might expect youth who are not out to a parent, or who are out but were hesitant to ask for parental consent to participate in the study, would report greater identity struggles, such as concealment motivation, acceptance concerns, and possible internalized homonegativity. The inclusion of a substantial number of individuals who are not involved in community organizations, out to a parent, or self-identified as LGB, while challenging to recruit, might reveal additional profiles of identity development.

A third limitation is with regard to sample size. Despite a moderate sample size, sufficient to detect medium to large effect size at power = .80 (Cohen, 1992), analyses may have neglected to detect smaller effect sizes. Some research has begun to examine the interaction between ethnic and sexual minority statuses (i.e., gay and African-American; Gallor & Fassinger, 2010). Despite ethnic and sexual orientation diversity in this sample, this study could not evaluate these types of interactions due to sample size limitations. Additionally, the LPA revealed some results that might have suggested a three-group solution fit the data, but this solution was unstable due to small profile sizes (i.e., n = 13). An increased number of participants, as well as an increased diversity of participants, might yield additional profile solutions not represented in this study.

Research and Clinical Implications

Results of the current investigation may have important implications for clinical work and policy regarding LGB youth. Although approximately 20% of youth in the study fell into the identity struggles profile, the majority did not. This highlights the considerable resiliency of sexual minority youth against identity struggles in the face of negative family reactions and societal stigma, and it suggests that parental acceptance and sexuality-specific social support may be two protective factors. Results of this study also highlight the need for family-centered approaches to intervention with LGB youth (Willoughby & Doty, 2010). Clinically, treatments that improve parents' ability to offer acceptance and sexuality-specific social support to their youth may be crucial for LGB identity development. Given the implications of identity struggles, such as the data linking internalized homonegativity with mental health difficulties (Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010), it is important to intervene with families and help support acceptance. However, not all parents will be able to offer acceptance, due to their own expectations for their child, as well as their beliefs and values, and, therefore, interventions for youth should focus on barriers to obtaining acceptance. For instance, youth may benefit from “coming out” only to parents whom they perceive would be likely to offer acceptance, or to seek alternative sources of acceptance and support from peers and extended family. From a policy perspective, the present study provides data that suggest that when LGB youth feel that they have support and assistance that is not just general but focused on their sexuality, particularly from parents, fewer youth will experience struggles about who they are. LGB youth are likely to benefit from policies, programs, and interventions that improve their ability to access acceptance and support, especially from their families.

Conclusion

Results of the current investigation highlight that family responses are related in important ways to perceptions of self and identity in LGB youth. In comparison to prior research, which has primarily used single dimensions and variable-centered approaches to assess identity, the current study, by using LPA, was able to show that parental rejection of youth's sexual orientation increases the likelihood of youth experiencing identity struggles. When young people are less sure of themselves and less secure in who they are, it may be difficult for them to assert themselves or protect themselves in vulnerable situations. The adolescent literature has shown consistent links between low self-esteem and victimization (Hawker & Boulton, 2000). Recent suicides of young gay men have shown how devastating the consequences of a combination of low self-esteem and peer victimization can be in LGB youth. Along with a stronger sense of confidence and identity, sexuality-specific social support may provide LGB youth with the strength to feel good about themselves, even if they are in vulnerable situations. Our study found that when youth felt that parents provided support and assistance with solving problems related to their sexual orientation, youth were more likely to feel more positive about their own LGB identity.

Earlier research has established the importance of identity for psychosocial outcomes (Morris, 1997; Rosario et al., 2001; Rosario et al., 2011). This study examines predictors of identity, and in so doing, provides avenues for prevention of LGB youth difficulties by focusing on how important parents are to these youth. Two specific targets for intervention are how parents respond to youth's disclosure of sexual orientation and, over time, how well they are able to help their LGB children cope with the stressors that come from being a sexual minority.The process of accepting that a child may be lesbian, gay, or bisexual may be a very difficult one for parents. Parents even may feel rejected when their children come out. Data from the present study, however, make it clear how strong ties remain between LGB youth and their parents. Particularly for parents who are struggling, understanding how much influence their support has on their children's sense of self may, in many cases, provide the motivation needed to help parents accept and embrace their LGB children.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD055372-01A2) awarded to Neena M. Malik. We thank all of the families who so graciously gave of their time to participate in the research project.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Archer SL, Grey JA. The sexual domain of identity: Sexual statuses of identity in relation to psychosocial sexual health. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2009;9(1):33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. The American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badgett L. Best Practices for Asking Questions about Sexual Orientation on Surveys. The Williams Institute; UC Los Angeles: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Mohr JJ. Adaptation to sexual orientation stigma: A comparison of bisexual and lesbian/gay adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54(3):306–319. [Google Scholar]

- Beals K, Peplau LA. Disclosure Patterns Within Social Networks of Gay Men and Lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality. 2006;51(2):1–20. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeler J, DiProva V. Family adjustment following disclosure of homosexuality by a member: Themes discerned in narrative accounts. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1999;25:443–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1999.tb00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenson KR, Crawford TN, Cohen P, Brook J. Implications of Identification with Parents and parents' Acceptance for Adolescent and Young Adult Self-esteem. Self and Identity. 2005;4(3):289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Branje ST, van Aken MG, van Lieshout CM. Relational support in families with adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16(3):351–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass VC. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality. 1979;4(3):219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley CH. Human nature and the social order. Scribner's; New York: 1902. [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR. Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths ages 14 to 21. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;7:433–456. [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:361–371. doi: 10.1037/h0080345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Hershberger SL. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings: Personal challenges and mental health problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:421–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00942151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. A dynamical systems approach to the development and expression of female same-sex sexuality. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007;2(2):142–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty N, Willoughby BB, Lindahl KM, Malik NM. Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(10):1134–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Stein TS. Sexual orientation identity formation among gay, lesbian and bisexual youths: Multiple patterns of milestone. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12(2):167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Stein TS, Harter KM, Allison A, Nye CL. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Separation-individuation, parental attitudes, identity consolidation, and well-being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28(6):719–739. [Google Scholar]

- Gallor SM, Fassinger RE. Social support, ethnic identity, and sexual identity of lesbians and gay men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services: The Quarterly Journal of Community & Clinical Practice. 2010;22(3):287–315. [Google Scholar]

- Hawker DJ, Boulton MJ. Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41(4):441–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson JM, Reise SP, Kim K. Detecting mixtures from structural model differences using latent variable mixture modeling: A comparison of relative model-fit statistics. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14:202–226. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Assessing heterosexuals' attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: A review of empirical research with the ATLG scale. In: Greene B, Herek GM, Greene B, Herek GM, editors. Lesbian and gay psychology: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA US: 1994. pp. 206–228. [Google Scholar]

- Lesbian Gay Bisexual Youth Sexual Orientation Measurement Work Group . Measuring Sexual Orientation of Young People in Health Research. Gay and Lesbian Medical Association; San Francisco, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA. Modeling the Drop-Out Mechanism in Repeated-Measures Studies. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90(431):1112–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–778. [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Development and validation of ego identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1966;3:551–558. doi: 10.1037/h0023281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulis ST. Privacy as a social issue and behavioral concept. Journal of Social Issues. 2003;59(2):243–261. [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon AC. Latent class analysis. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan G. On bootstrapping the likelihood ratio test statistic for the number of components in a normal mixture. Applied Statistics. 1987;36:318–324. [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan G, Peel D. Finite mixture models. Wiley; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mead GH. Mind, self and society. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Meeus W. The study of adolescent identity formation 2000–2010: A review of longitudinal research. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(1):75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Colten M. Sampling gay men: Random digit dialing versus sources in the gay community. Journal of Homosexuality. 1999;37(4):99–110. doi: 10.1300/J082v37n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JJ, Fassinger RE. Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2000;33:66–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JJ, Fassinger RE. Self-acceptance and self-disclosure of sexual orientation in lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: An attachment perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2003;50(4):482–495. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JJ, Kendra MS. Revision and extension of a multidimensional measure of sexual minority identity: The Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58(2):234–245. doi: 10.1037/a0022858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JF, Waldo CR, Rothblum ED. A model of predictors and outcomes of outness among lesbian and bisexual women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71(1):61–71. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JF. Lesbian coming out as a multidimensional process. Journal of Homosexuality. 1997;33:1–22. doi: 10.1300/J082v33n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. Second-generation structural equation modeling with a combination of categorical and continuous latent variables: New opportunities for latent class-latent growth modeling. In: Collins LM, Sayer AG, Collins LM, Sayer AG, editors. New methods for the analysis of change. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC US: 2001. pp. 291–322. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Sixth Edition Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24(6):882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;55:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(8):1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JF, Simons RL. Family factors, self-esteem, and adolescent depression. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51(1):125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson NS. Evaluating the nature of perceived support and its relation to perceived self-worth in adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1995;5(2):253–280. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Different patterns of sexual identity development over time: Implications for the psychological adjustment of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Journal of Sex Research. 2011;48(1):3–15. doi: 10.1080/00224490903331067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Predicting different patterns of sexual identity development over time among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: A cluster analytic approach. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;42(3–4):266–282. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9207-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Ethnic/Racial Differences in the Coming-Out Process of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youths: A Comparison of Sexual Identity Development Over Time. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10(3):215–228. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Hunter J, Maguen S, Gwadz M, Smith R. The coming-out process and its adaptational and health-related associations among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Stipulation and exploration of a model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29(1):113–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1005205630978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz R, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, Sanchez J. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;23(4):205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM. Research on adolescent sexual orientation: Development, health disparities, stigma, and resilience. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(1):256–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. A critique of research on sexual-minority youths. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24(1):5–13. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Coming out to parents and self-esteem among gay and lesbian youths. Journal of Homosexuality. 1989;18:1–35. doi: 10.1300/J082v18n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Diamond LM. Sexual identity trajectories among sexual-minority youths: Gender comparisons. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2000;29:419–440. doi: 10.1023/a:1002058505138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(2):147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Sclove L. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika. 1987;52:333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Troiden RR. Gay and Lesbian Identity: A Sociological Analysis. General Hall; Dix Hills, NY: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Vaux A, Riedel S, Stewart D. Modes of social support: The social support behaviors (SS-B) scale. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1987;15:209–237. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, Magidson J. Latent class cluster analysis. In: Hagenaars JA, McCutcheon AL, editors. Advances in Latent Class Analysis. Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Westin AF. Privacy and freedom. Atheneum; New York: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby BB, Doty ND. Brief cognitive behavioral family therapy following a child's coming out: A case report. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(1):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby BB, Doty ND, Malik NM. Victimization, family rejection, and outcomes of gay, lesbian, and bisexual young people: The role of negative GLB identity. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2010;6(4):403–424. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby BB, Malik NM, Lindahl KM. Parental reactions to their sons' sexual orientation disclosures: The roles of family cohesion, adaptability, and parenting style. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2006;7(1):14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington RL, Navarro RL, Savoy H, Hampton D. Development, reliability, and validity of the Measure of Sexual Identity Exploration and Commitment (MOSIEC) Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(1):22–33. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. Evaluating latent class analyses in qualitative phenotype identification. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 2006;50:1090–1104. [Google Scholar]