Abstract

Objective

Adipose tissue has now emerged as a powerful endocrine organ via the production of adipokines. Visfatin, a novel adipokine with diabetogenic and immunomodulatory properties has been implicated in the pathophysiology of insulin resistance in patients with obesity and Type-2 diabetes mellitus. The aim of this study was to determine whether there are changes in the maternal plasma concentration of visfatin with advancing gestation and as a function of maternal weight.

Study design

In this cross-sectional study, maternal plasma concentrations of visfatin were determined in normal weight and overweight/obese pregnant women in the following gestational age groups: 1) 11–14 weeks (n= 52); 2) 19–26 weeks (n=68); 3) 27–34 weeks (n=93); and 4) >37 weeks (n=60). Visfatin concentrations were determined by ELISA. Non parametric statistics were used for analysis.

Results

1) The median maternal plasma visfatin concentration was higher in pregnant women between 19–26 weeks of gestation than that of those between 11–14 weeks of gestation (p<0.01) and those between 27–34 weeks of gestation (p <0.01); 2) among normal weight pregnant women, the median plasma visfatin concentrations of women between 19–26 weeks of gestation was higher than that of those between 11–14 weeks (p<0.01) and those between 27–34 weeks (p < 0.01); and 3) among overweight/obese patients, the median maternal visfatin concentration was similar between the different gestational age groups

Conclusion

The median maternal plasma concentration of visfatin peaks between 19–26 and has a nadir between 27–34 weeks of gestation. Normal and overweight/obese pregnant women differed in the pattern of changes in circulating visfatin concentrations as a function of gestational age.

Keywords: Visfatin, pregnancy, adipokines, overweight, obesity

Introduction

Adipose tissue, originally considered to be a passive depot for energy storage, has recently emerged as a powerful endocrine organ via the production of adipokines.61;62;154;185–187 The adipokine family includes structurally and functionally diverse and highly active peptides and proteins. Indeed, the adipokines encompass cytokines [e.g. tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α76;77;96;128;190 and interleukin (IL)-639;59;127;151;191;192], chemokines (e.g. monocyte chemoattractant protein-1),122;168 mediators of vascular hemostasis (e.g. plasminogen activator inhibitor-1),5;47;174 blood pressure (e.g angiotensinogen),84;93 and angiogenesis (e.g. vascular endothelial growth factor),37;50 as well as hormones regulating glucose homeostasis (adiponectin,8;15;78;85;86;115;121;130;169 resistin,12;75;97;105;178 and leptin51;60;63;69;110;114;203). Much attention has been focused on the endocrine actions of the adipokines, particularly to their suggested roles in regulating metabolic processes. Adipokines have been implicated in the pathophysiology of insulin resistance,25;99;112;124;158;175;179 obesity,49;100;199 hyperlipidemia,52;189 and atherosclerosis,143–145 thus providing a putative mechanistic linkage between obesity and abnormal metabolic conditions.

Recently, the important role of adipokines has been corroborated in normal human gestation and common complications of pregnancy: 1) increased circulating maternal concentrations of leptin,10;94;99;124 C-reactive protein (CRP),124 TNF-α,7;10;98;99;124;195 resistin35 and visfatin102;107 were reported in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Consistent with these findings, patients with GDM had lower concentrations of adiponectin than normal pregnant women;10;40;98;156;158;184;188;197 2) overweight pregnant women have a lower plasma concentration of adiponectin73;134 and a higher concentration of leptin73 than non-obese pregnant women; and 3) preeclampsia is associated with increased concentrations of leptin,4;33;73;87;113;123;136;137;147;183 visfatin,54 and TNF-α,38;101;172 as well as decreased concentrations of resistin34;40 and altered maternal circulating adiponectin.40;71;73;90;113;131;135;155;180

Visfatin, a newly discovered 52 kDa adipokine, had already been identified more than a decade ago as a growth factor for early B cell, termed pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF).81;119;140;166;200 The re-discovery of visfatin as an adipose tissue derived hormone has facilitated the investigation of its metabolic effects. This adipokine is preferentially produced by visceral adipose tissue,79;171;182 and exerts insulin-mimicking effects171;198 through the activation of an insulin receptor. In vitro exposure of adipocytes to glucose results in increased secretion of visfatin,67 and visfatin deficient mice have an impaired glucose tolerance.159 Studies in humans have demonstrated that administration of glucose results in an increase in circulating visfatin concentration.67 In addition there is a higher circulating concentration of this hormone in patients with Type-2 diabetes mellitus (Type-2 DM) when compared to non-diabetic subjects.36;55;111;167

Only few studies have addressed the concentration of visfatin in pregnant women.31;53;54;65;102;107;116;117;120 Most of these reports are confined to complications of pregnancy such as preeclampsia53;54 fetal growth restriction53;116 and GDM.31;65;102;107 Only a single study reported maternal visfatin concentrations along gestation120 and there is no information available regarding the comparison between circulating visfatin in normal and overweight pregnant women. Thus, the aims of this study were to determine whether there are changes in maternal plasma concentration of visfatin associated with advancing gestation and as a function of maternal weight.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted by searching our clinical database and bank of biological samples. Two-hundred seventy three pregnant women with a normal singleton pregnancy were included in the study. The inclusion criteria were: 1) no medical, obstetrical or surgical complications; 2) intact membranes; 3) delivery of a term neonate (>37 weeks) and 4) birth weight above the 10th percentile.6 Women with multiple pregnancies, GDM and fetal congenital malformations were excluded.

Maternal blood samples were obtained once from each pregnant woman at the following gestational ages: 1) 11–14 weeks (n=52); 2) 19–26 weeks (n=68); 3) 27–34 weeks (n=93); and 4) >37 weeks (n=60). Blood was centrifuged at 1300 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The plasma obtained was stored at −80°C until the assay was performed.

The body mass index (BMI) in the first trimester was calculated according to the following formula: weight (kg)/height (m)2. According to the definitions of the World Health Organization (WHO)1 normal BMI was defined as 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 and overweight/obese as BMI ≥25 kg/m2.

All women provided written informed consent prior to the collection of maternal blood samples. The utilization of samples for research purposes was approved by the institutional review boards of Wayne State University, Sotero del Rio Hospital (Chile) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD/ NIH/DHHS). Many of these samples have been previously employed to study the biology of inflammation, hemostasis, angiogenesis, and growth factors concentrations in normal pregnant women and those with pregnancy complications.

Human visfatin C-terminal immunoassay

The concentrations of visfatin in maternal plasma were determined using specific and sensitive enzyme immunoassays purchased from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc (Belmont, CA, USA). Visfatin C-terminal assays were validated in our laboratory for human plasma prior to the conduction of this study. Validation included spike and recovery experiments, which produced parallel curves indicating that maternal plasma matrix constituents did not interfere with antigen- antibody binding in this assay system. Visfatin enzyme immunoassays are based on the principle of competitive binding and were conducted according to the manufacturer recommendations. Briefly, assay plates are pre-coated with a secondary antibody and the non-specific binding sites have been blocked. Standards and samples were incubated in the assay plates along with primary antiserum and biotinylated peptide. The secondary antibody in the assay plates bound to the Fc fragment of the primary antibody whose Fab fragment competitively bound with both the biotinylated peptide and peptide standard or targeted peptide in the samples. Following incubation, the assay plates were repeatedly washed to remove unbound materials and incubated with a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (SA-HRP) solution. Following incubation, unbound enzyme conjugate was removed by repeated washing and a substrate solution was added to the wells of the assay plates and color developed in proportion to the amount of biotinylated peptide-SA-HRP complex but inversely proportional to the amount of peptide in the standard solutions or the samples. Color development was stopped with the addition of an acid solution and the intensity of color was read using a programmable spectrophotometer (SpectraMax M2, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA USA). Maternal plasma concentrations of visfatin C were determined by interpolation from individual standard curves composed of human visfatin peptide. The calculated inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) for visfatin C-terminal immunoassays in our laboratory were 5.3% and 2.4%, respectively. The sensitivity was calculated to be 0.04 ng/ml.

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were used to test for normal distribution of the data. Data were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) or median and range. Non-parametric methods were used for parameters which were not normally distributed such as maternal visfatin concentrations and comparisons among groups were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test with post hoc test (Mann–Whitney U). For those parameters which were normally distributed, parametric tests were used for analysis and the comparisons among groups were performed using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni adjustment for the calculated p-value in order to maintain the significance level at 0.05.

Correlation between visfatin and gestational age at sampling, maternal age, maternal BMI, birth weight and storage time was conducted with the Spearman’s rank test. The statistical package employed was SPSS 14 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL USA). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The clinical and obstetrical characteristics of the study groups are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in maternal age, first trimester BMI, gestational age at delivery and birth weight among the four gestational age groups.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population

| 11–14 weeks (n = 52) |

19–26 weeks (n = 68) |

27–34 weeks (n = 93) |

≤37 weeks (n = 60) |

P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 25.0 (22.0–31.0) | 27.0 (22.0–33.0) | 25.0 (21.0–31.0) | 27.0 (22.0–30.0) | 0.81 |

| Parity | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | 0.74 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.7 (23.2–27.0) | 22.8 (21.0–25.2) | 23.4 (21.6–26.3) | 23.5 (22.0–25.6) | 0.45 |

| Gestational age at sampling (weeks) | 13.0 (12.2–13.5) | 20.7 (20.0–21.5) | 31.7 (27.8–33.0) | 39.5 (38.6–40.4) | <0.01 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 39.4 (38.7–40.4) | 39.7 (38.7–40.4) | 40.0 (39.0–40.4) | 39.5 (38.6–40.1) | 0.33 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3420 (3205–3660) | 3380 (3120–3740) | 3470 (3235–3702) | 3415 (3157–3717) | 0.67 |

Values are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR); BMI – Body Mass Index

Kruskal-Wallis test

Maternal plasma concentrations of visfatin in normal pregnancy

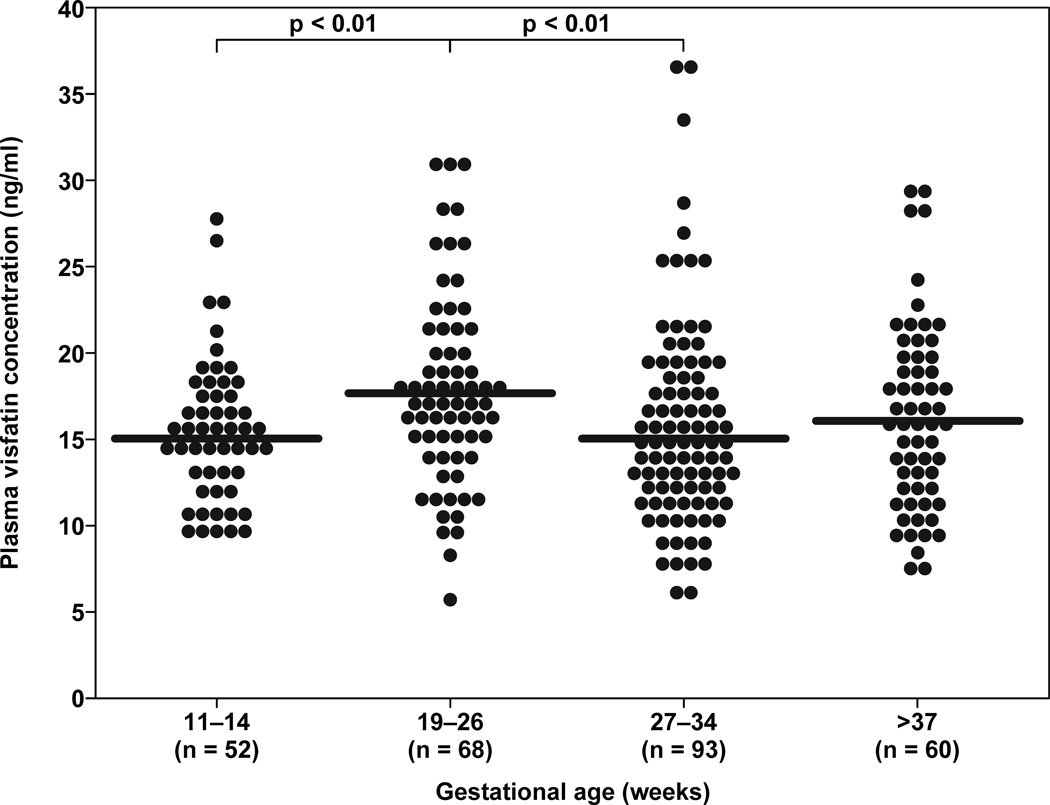

Visfatin was detected in the plasma of all subjects. Pregnant women between 19–26 weeks of gestation had a higher median concentration of visfatin than those between 11–14 weeks of gestation (median: 17.5 ng/ml range: 5.6–31.0 vs. 15.0 ng/ml, 9.3–27.8, respectively; p<0.01). Similarly, pregnant women between 19–26 weeks of gestation had a higher median concentration of visfatin than those between 27–34 weeks of gestation (median: 17.5 ng/ml range: 5.6–31.0 ng/ml vs. 14.8 ng/ml, 5.6–37.0, respectively p <0.01) (Figure 1). There was no significant difference in the median maternal plasma visfatin concentration among the other groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of median maternal plasma concentrations of visfatin between 11–14, 19–26, 27–34, and ≥37 weeks of gestation. Pregnant women between 19–26 weeks of gestation had a higher median concentration of visfatin than women between 11–14 weeks of gestation (median: 17.5 ng/ml range: 5.6–31.0 vs. 15.0 ng/ml, 9.3–27.8, respectively; p<0.01). Similarly, pregnant women between 19–26 weeks of gestation had a higher median concentration of visfatin than women between 27–34 weeks of gestation (median: 17.5 ng/ml range: 5.6–31.0 vs. 14.8 ng/ml, 5.6–37.0, respectively; p <0.01). There was no difference in the median maternal plasma visfatin concentration between the other groups.

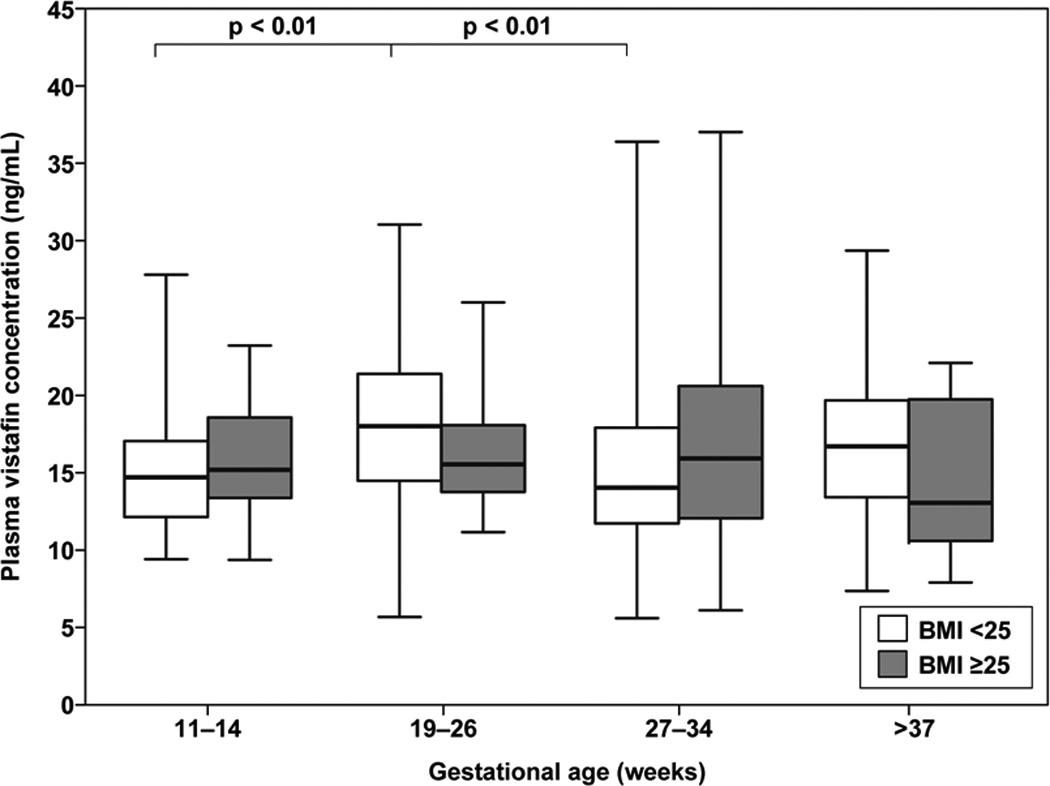

Comparison between maternal visfatin in normal and overweight/obese women

Among normal weight pregnant women, the median plasma visfatin concentrations between 19–26 weeks of gestation was higher than that of those between 11–14 weeks (median: 18.1 ng/ml, range: 5.6–31.0 vs. 14.7 ng/ml, 9.4–27.8, respectively; p < 0.01) and those between 27–34 weeks (median: 18.1 ng/ml, range: 5.6–31.0 vs. 13.9 ng/ml, 5.6–36.4, respectively; p < 0.01) (Figure 2). In contrast, among overweight/obese patients, the median maternal plasma visfatin concentration did not significantly different among the various gestational age groups.

Figure 2.

Median maternal plasma visfatin concentrations during pregnancy in women of normal weight (BMI ≥25) and overweight/obese (BMI >25). Among normal weight pregnant women, the median plasma visfatin concentration of women between 19–26 weeks of gestation was higher than those between 11–14 weeks (median: 18.1 ng/ml range: 5.6–31.0 vs. 14.7 ng/ml, 9.4–27.8, respectively; p < 0.01) and those between 27–34 weeks (median: 18.1 ng/ml range: 5.6–31.0 vs. 13.9 ng/ml, 5.6–36.4, respectively; p < 0.01). Among overweight/obese patients, the median maternal visfatin concentration was comparable between the different gestational age groups.

The median maternal plasma visfatin concentration was compared between normal and overweight/obese patients regardless of gestational age group (Figure 2). There was no correlation between the maternal plasma visfatin concentration and maternal age, gestational age at blood collection or birthweight irrespective of BMI category or gestational age group.

Discussion

Principal findings of the study

1) Pregnant women between 19–26 weeks of gestation had a significantly higher median plasma concentration of visfatin than those between 11–14 weeks and 27–34 weeks of gestation; 2) among normal weight women, the median plasma visfatin concentration at 19–26 weeks of gestation was higher than those between 11–14 weeks and those between 27–34 weeks; 3) among overweight patients, the median maternal visfatin concentration was similar between the different gestational age groups.

Adipokines - a new culprit in insulin resistance during pregnancy

Pregnancy is a unique physiologic state characterized by profound and transitory insulin resistance.17;21–23;26–28;42;58;64;103;104;106;109;149;157;164;177 This important metabolic alteration is thought to be induced by placental hormones. Several lines of evidence support this view: 1) in vitro, exposure of adipocytes to progesterone, cortisol, prolactin, or human placental lactogen, induced post binding defect in insulin action;163 2) insulin resistance can be induced by administration of human placental lactogen (HPL),92;165 progesterone,14;41;91 estrogen41;150 and glucocorticosteroids92 to non-pregnant subjects and mice;13 and 3) insulin resistance during pregnancy rises in the third trimester17;21;29;164;176;193 with the increase in the placental hormone secretion.

Previously, placental hormones thought to be the only culprits for insulin resistance in pregnancy. However, with the recognition of the adipose tissue as a powerful endocrine organ,45;88;89;161 its role in the pathophysiology of insulin resistance via the production and secretion of adipokines61;62;154;185–187 has been established. The adipokine family includes highly active molecules such as: IL-6,191;192 TNF-α,77;190 leptin,51;60 adiponectin,8;15;85;121 resistin,12;75;97;105;178 and others.16;105;146;160;161 Accumulating evidence suggests that adipokines play a role in the regulation of insulin resistance during human pregnancy: 1) maternal serum concentrations of leptin,120;124;126 adiponectin,7;25;43;112;124;158 TNF-α,7;19;99;124–126 resistin71 and visfatin120 are correlated with insulin resistance indices such as homeostasis model of assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR); 2) patients with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) have increased concentrations of leptin,10;94;99;124 C-reactive protein (CRP),124 TNF-α,7;10;98;99;124;195 resistin35 and visfatin,102;107 and lower concentrations of adiponectin than normal pregnant women;10;40;98;156;158;184;188;197 and 3) high concentrations of CRP152;196 and leptin,153 as well as low concentrations of adiponectin194 in first and early second trimester, are associated with increase risk for GDM, suggesting a role for these adipokines in the pathophysiology of this condition.

Visfatin is a novel adipokine with metabolic and immunoregulatoric properties

Visfatin, a newly discovered 52 kDa adipokine, is preferentially produced by visceral adipose tissue.79;171;182 However, this protein is not tissue specific, and it can be expressed in placenta, fetal membranes95;119;132;133;139–142 and myometrium,48 as well as in bone marrow, liver, muscle,166 heart, lung, kidney,166 macrophages,44 and neutrophils.81;166;200 The specific physiologic role of visfatin has eluded elucidation; nevertheless, increasing body of evidence suggests that this hormone has immunoregulatory and metabolic properties.

The role of visfatin in the regulation of the inflammatory response has been highlighted in several reports: 1) visfatin promotes the growth of B cell precursors;166 2) in vitro, visfatin up-regulates the production of the pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-10) by human monocytes, in a dose dependent manner;129 3) the expression of visfatin is increased following exposure to TNF-α (in monocytes,44 macrophages80 and neutrophils81), IL-6 (synovial138 and amniotic epithelial139 cells), IL-8, as well as granulocyte/macrophage colony stimulating factor (in neutrophils81); 4) the expression of visfatin increased in cells retrieved by bronchoalveolar lavage from patients with acute lung injury200 in neutrophils of septic patients,81 and in lung tissue of animals with acute lung injury;201 5) patients with the -1001G allele in the visfatin gene have increased risk of developing ARDS than wild-type homozygotes, while the -1543T allele is associated with decreased risk of developing ARDS in septic shock patients;11 and 6) patients with chronic inflammatory disorders (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis) have an elevated serum visfatin concentration.81;200;201

The evidence for the metabolic effect of this hormone includes: 1) visfatin has insulin mimetic properties;171;198 2) in vitro exposure of adipocytes to glucose results in increase secretion of visfatin;67 3) serum concentration of visfatin in humans correlates with the amount of intra-visceral fat as determined by computerized tomography scan;167 4) administration of glucose to human subjects results in an increase in circulating visfatin concentration;67 5) patients with Type-2 diabetes mellitus or metabolic syndrome56;57 have higher circulating visfatin concentrations than non-diabetic subjects;36;55;111;167 and 6) visfatin serum concentrations are higher in patients with GDM102;107 than in normal pregnant women.

Changes in plasma visfatin concentration during normal pregnancy

Our findings that the median maternal plasma concentration of visfatin peaks between 19–26 weeksand has a nadir between 27–34 weeks of gestation only in normal weight women, are novel. There are only a few reports regarding circulating visfatin concentrations in pregnant women.31;53;65;102;107;116;117;120 Indeed, only a single study reported the results of comparison of maternal visfatin concentrations between the three trimesters of pregnancy,120 and none included a comparison of circulating maternal visfatin concentrations between normal and overweight pregnant women. Our results are in agreement with the findings reported by Mastorakos et al.120 in which median concentration of visfatin were higher in the second (24–26 weeks) and third trimester (34–36 weeks) than those in the first trimester (10–12 weeks) in a longitudinal study of 80 normal lean women. Our findings extend the latter report by demonstrating that the increase in the median plasma visfatin concentration is confined to normal weight pregnant women. In addition, we included pregnant women with a wide range of gestational age; thus, we were able to report a nadir in maternal visfatin concentrations during the early third trimester.

Why are there fluctuations in circulating visfatin with advancing gestation?

Given the diabetogenic effect of visfatin, it is tempting to suggest that the median visfatin concentration increase during pregnancy in association with insulin resistance and the increase in maternal weight. Indeed, several reports concerning non-pregnant subjects have argued in favor of this association.18;36;55;66–68;111;167 Our findings regarding the nadir in the median plasma concentration of visfatin in the early third trimester, does not support this hypothesis. Of note, recent reports have challenged the association between visfatin and insulin resistance,9;20;46;70;148 BMI or obesity.46;148 Hence, additional explanations must be thought in order to explain our results.

Prima facie, our findings indicate that there is no association between weight gain during pregnancy and the fluctuations in the median visfatin concentrations along gestation. However, previous studies have indicted that the highest maternal weight gain rate (expresses as the increase in body weight per week) occurs during the second trimester.3;72;74;170 Furthermore, the fetal weight gain is lower during the second trimester than in the third trimester; thus, second trimester maternal weight gain reflects mainly maternal tissue growth. In summary, the pattern of the alteration in maternal plasma visfatin concentration with advancing gestation in normal weight pregnant women may follow the changes in the rate of maternal weight gain rather than weight gain per se.

Pregnancy, maternal BMI and circulating visfatin concentration - is increased BMI associated with alteration in circulating visfatin?

The finding that normal and overweight/obese pregnant women had a comparable median visfatin concentration is novel. The association between circulating visfatin and obesity, BMI and visceral fat depot is still shrouded with uncertainty. Indeed, the lack of an association between circulating visfatin and BMI,36;46;53;55;83;102;118;173;181;202 as well as a positive 18;32;108;167 and negative31 association between the two have been reported. Other investigators could not demonstrate an association between visceral fat mass and plasma visfatin concentrations.18 Moreover, both higher18;32;56;57;66;83;167;202 and lower82;148 concentrations of visfatin in obese, than in normal subjects, were reported. Although one can explain some of the discrepancies by differences in the methods and the characteristics of the various study groups, currently, it is unclear whether or not circulating visfatin concentrations are associated with body weight and adipose tissue. In summary, the comparable median maternal visfatin concentration between normal and overweight/obese women reported herein, support the recent studies challenging the suggested association between visfatin and overweight and obesity.

We hypothesized that, in normal weight healthy pregnant women, the alteration in visfatin concentrations with advancing gestation corresponds with the rate of maternal weight gain. Interestingly, during pregnancy, overweight and obese patients gain less weight2;24;30;162 and at a slower rate3 than normal weight women. Thus, it is tempting to suggest that the different pattern of maternal circulating visfatin concentrations with advancing gestation in overweight than in normal weight women reflects the decreased rate and the lower absolute weight gain in overweight pregnant patients.

Currently, clinical data concerning maternal circulating visfatin concentrations is scant. Indeed, this is the first description of a nadir in maternal visfatin concentrations in the early third trimester and a blunted change in maternal circulating visfatin with advancing gestational age in overweight pregnant women. A cause and effect relationship between BMI and maternal circulating visfatin concentrations cannot be discern from the data of the present study; however, a plausible explanation for our result can be the differences in weight gain rate in the different trimesters and between normal and overweight pregnant women, suggesting a role for visfatin in physiologic metabolic alterations of human pregnancy.

Acknowledgment

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS.

Reference List

- 1.Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. World Health Organ Tech.Rep.Ser. 2003;916 i-149, backcover. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Supplement 1. American Diabetes Association: clinical practice recommendations 2000. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(Suppl 1):S1–S116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrams B, Carmichael S, Selvin S. Factors associated with the pattern of maternal weight gain during pregnancy. Obstet.Gynecol. 1995;86:170–176. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00119-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acromite M, Ziotopoulou M, Orlova C, Mantzoros C. Increased leptin levels in preeclampsia: associations with BMI estrogen and SHBG levels. Hormones.(Athens.) 2004;3:46–52. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.11111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alessi MC, Peiretti F, Morange P, Henry M, Nalbone G, Juhan-Vague I. Production of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 by human adipose tissue: possible link between visceral fat accumulation and vascular disease. Diabetes. 1997;46:860–867. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.5.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet.Gynecol. 1996;87:163–168. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altinova AE, Toruner F, Bozkurt N, Bukan N, Karakoc A, Yetkin I, et al. Circulating concentrations of adiponectin and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in gestational diabetes mellitus. Gynecol.Endocrinol. 2007;23:161–165. doi: 10.1080/09513590701227960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Miyagawa J, et al. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun. 1999;257:79–83. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arner P. Visfatin--a true or false trail to type 2 diabetes mellitus. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2006;91:28–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ategbo JM, Grissa O, Yessoufou A, Hichami A, Dramane KL, Moutairou K, et al. Modulation of adipokines and cytokines in gestational diabetes and macrosomia. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2006;91:4137–4143. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajwa EK, Yu CL, Gong MN, Thompson BT, Christiani DC. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor gene polymorphisms and risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1290–1295. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260243.22758.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee RR, Rangwala SM, Shapiro JS, Rich AS, Rhoades B, Qi Y, et al. Regulation of fasted blood glucose by resistin. Science. 2004;303:1195–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1092341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbour LA, Shao J, Qiao L, Pulawa LK, Jensen DR, Bartke A, et al. Human placental growth hormone causes severe insulin resistance in transgenic mice. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2002;186:512–517. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beck P. Progestin enhancement of the plasma insulin response to glucose in Rhesus monkeys. Diabetes. 1969;18:146–152. doi: 10.2337/diab.18.3.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg AH, Combs TP, Scherer PE. ACRP30/adiponectin: an adipokine regulating glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Endocrinol.Metab. 2002;13:84–89. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00524-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berg AH, Scherer PE. Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Circ.Res. 2005;96:939–949. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163635.62927.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergman RN, Finegood DT, Ader M. Assessment of insulin sensitivity in vivo. Endocr.Rev. 1985;6:45–86. doi: 10.1210/edrv-6-1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berndt J, Kloting N, Kralisch S, Kovacs P, Fasshauer M, Schon MR, et al. Plasma visfatin concentrations and fat depot-specific mRNA expression in humans. Diabetes. 2005;54:2911–2916. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bo S, Signorile A, Menato G, Gambino R, Bardelli C, Gallo ML, et al. C-reactive protein and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in gestational hyperglycemia. J.Endocrinol.Invest. 2005;28:779–786. doi: 10.1007/BF03347566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bottcher Y, Teupser D, Enigk B, Berndt J, Kloting N, Schon MR, et al. Genetic variation in the visfatin gene (PBEF1) and its relation to glucose metabolism and fat-depot-specific messenger ribonucleic acid expression in humans. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2006;91:2725–2731. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchanan TA, Metzger BE, Freinkel N, Bergman RN. Insulin sensitivity and B-cell responsiveness to glucose during late pregnancy in lean and moderately obese women with normal glucose tolerance or mild gestational diabetes. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1990;162:1008–1014. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91306-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.BURT RL. Peripheral utilization of glucose in pregnancy. III. Insulin tolerance. Obstet.Gynecol. 1956;7:658–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butte NF. Carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in pregnancy: normal compared with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 2000;71:1256S–1261S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1256s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catalano PM. Increasing maternal obesity and weight gain during pregnancy: the obstetric problems of plentitude. Obstet.Gynecol. 2007;110:743–744. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000284990.84982.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catalano PM, Hoegh M, Minium J, Huston-Presley L, Bernard S, Kalhan S, et al. Adiponectin in human pregnancy: implications for regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1677–1685. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Catalano PM, Huston L, Amini SB, Kalhan SC. Longitudinal changes in glucose metabolism during pregnancy in obese women with normal glucose tolerance and gestational diabetes mellitus. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1999;180:903–916. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70662-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Catalano PM, Roman-Drago NM, Amini SB, Sims EA. Longitudinal changes in body composition and energy balance in lean women with normal and abnormal glucose tolerance during pregnancy. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1998;179:156–165. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catalano PM, Tyzbir ED, Roman NM, Amini SB, Sims EA. Longitudinal changes in insulin release and insulin resistance in nonobese pregnant women. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1991;165:1667–1672. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90012-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Catalano PM, Tyzbir ED, Wolfe RR, Calles J, Roman NM, Amini SB, et al. Carbohydrate metabolism during pregnancy in control subjects and women with gestational diabetes. Am.J.Physiol. 1993;264:E60–E67. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.264.1.E60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cedergren MI. Optimal gestational weight gain for body mass index categories. Obstet.Gynecol. 2007;110:759–764. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000279450.85198.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan TF, Chen YL, Lee CH, Chou FH, Wu LC, Jong SB, et al. Decreased plasma visfatin concentrations in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J.Soc.Gynecol.Investig. 2006;13:364–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan TF, Chenb Sc YL, Chen HH, Lee CH, Jong SB, Tsai EM. Increased plasma visfatin concentrations in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil.Steril. 2007;88:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chappell LC, Seed PT, Briley A, Kelly FJ, Hunt BJ, Charnock-Jones DS, et al. A longitudinal study of biochemical variables in women at risk of preeclampsia. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2002;187:127–136. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen D, Dong M, Fang Q, He J, Wang Z, Yang X. Alterations of serum resistin in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Clin.Sci.(Lond) 2005;108:81–84. doi: 10.1042/CS20040225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen D, Fang Q, Chai Y, Wang H, Huang H, Dong M. Serum resistin in gestational diabetes mellitus and early postpartum. Clin.Endocrinol.(Oxf) 2007;67:208–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen MP, Chung FM, Chang DM, Tsai JC, Huang HF, Shin SJ, et al. Elevated plasma level of visfatin/pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2006;91:295–299. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Claffey KP, Wilkison WO, Spiegelman BM. Vascular endothelial growth factor. Regulation by cell differentiation and activated second messenger pathways. J.Biol.Chem. 1992;267:16317–16322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conrad KP, Miles TM, Benyo DF. Circulating levels of immunoreactive cytokines in women with preeclampsia. Am.J.Reprod.Immunol. 1998;40:102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1998.tb00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coppack SW. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipose tissue. Proc.Nutr.Soc. 2001;60:349–356. doi: 10.1079/pns2001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cortelazzi D, Corbetta S, Ronzoni S, Pelle F, Marconi A, Cozzi V, et al. Maternal and foetal resistin and adiponectin concentrations in normal and complicated pregnancies. Clin.Endocrinol.(Oxf) 2007;66:447–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costrini NV, Kalkhoff RK. Relative effects of pregnancy, estradiol, and progesterone on plasma insulin and pancreatic islet insulin secretion. J.Clin.Invest. 1971;50:992–999. doi: 10.1172/JCI106593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coustan DR, Carpenter MW. The diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(Suppl 2):B5–B8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cseh K, Baranyi E, Melczer Z, Kaszas E, Palik E, Winkler G. Plasma adiponectin and pregnancy-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:274–275. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dahl TB, Yndestad A, Skjelland M, Oie E, Dahl A, Michelsen A, et al. Increased expression of visfatin in macrophages of human unstable carotid and coronary atherosclerosis: possible role in inflammation and plaque destabilization. Circulation. 2007;115:972–980. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.665893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Despres JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006;444:881–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dogru T, Sonmez A, Tasci I, Bozoglu E, Yilmaz MI, Genc H, et al. Plasma visfatin levels in patients with newly diagnosed and untreated type 2 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Res.Clin.Pract. 2007;76:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eriksson P, Reynisdottir S, Lonnqvist F, Stemme V, Hamsten A, Arner P. Adipose tissue secretion of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in non-obese and obese individuals. Diabetologia. 1998;41:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s001250050868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Esplin MS, Fausett MB, Peltier MR, Hamblin S, Silver RM, Branch DW, et al. The use of cDNA microarray to identify differentially expressed labor-associated genes within the human myometrium during labor. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2005;193:404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Esposito K, Pontillo A, Di Palo C, Giugliano G, Masella M, Marfella R, et al. Effect of weight loss and lifestyle changes on vascular inflammatory markers in obese women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:1799–1804. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fain JN, Madan AK, Hiler ML, Cheema P, Bahouth SW. Comparison of the release of adipokines by adipose tissue, adipose tissue matrix, and adipocytes from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissues of obese humans. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2273–2282. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farooqi IS, Keogh JM, Kamath S, Jones S, Gibson WT, Trussell R, et al. Partial leptin deficiency and human adiposity. Nature. 2001;414:34–35. doi: 10.1038/35102112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farvid MS, Ng TW, Chan DC, Barrett PH, Watts GF. Association of adiponectin and resistin with adipose tissue compartments, insulin resistance and dyslipidaemia. Diabetes Obes.Metab. 2005;7:406–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2004.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fasshauer M, Bluher M, Stumvoll M, Tonessen P, Faber R, Stepan H. Differential regulation of visfatin and adiponectin in pregnancies with normal and abnormal placental function. Clin.Endocrinol.(Oxf) 2007;66:434–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fasshauer M, Waldeyer T, Seeger J, Schrey S, Ebert T, Kratzsch J, et al. Serum levels of the adipokine visfatin are increased in preeclampsia. Clin.Endocrinol.(Oxf) 2007;69:69–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fernandez-Real JM, Moreno JM, Chico B, Lopez-Bermejo A, Ricart W. Circulating visfatin is associated with parameters of iron metabolism in subjects with altered glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:616–621. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Filippatos TD, Derdemezis CS, Gazi IF, Lagos K, Kiortsis DN, Tselepis AD, et al. Increased plasma visfatin levels in subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Eur.J.Clin.Invest. 2008;38:71–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Filippatos TD, Derdemezis CS, Kiortsis DN, Tselepis AD, Elisaf MS. Increased plasma levels of visfatin/pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor in obese and overweight patients with metabolic syndrome. J.Endocrinol.Invest. 2007;30:323–326. doi: 10.1007/BF03346300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fisher PM, Sutherland HW, Bewsher PD. The insulin response to glucose infusion in normal human pregnancy. Diabetologia. 1980;19:15–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00258304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fried SK, Bunkin DA, Greenberg AS. Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese subjects release interleukin-6: depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 1998;83:847–850. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395:763–770. doi: 10.1038/27376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fruhbeck G. The Sir David Cuthbertson Medal Lecture. Hunting for new pieces to the complex puzzle of obesity. Proc.Nutr.Soc. 2006;65:329–347. doi: 10.1017/s0029665106005106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fruhbeck G, Gomez-Ambrosi J, Muruzabal FJ, Burrell MA. The adipocyte: a model for integration of endocrine and metabolic signaling in energy metabolism regulation. Am.J.Physiol Endocrinol.Metab. 2001;280:E827–E847. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.6.E827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fruhbeck G, Jebb SA, Prentice AM. Leptin: physiology and pathophysiology. Clin.Physiol. 1998;18:399–419. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.1998.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gabbe SG. Management of diabetes mellitus in pregnancy. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1985;153:824–828. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haider DG, Handisurya A, Storka A, Vojtassakova E, Luger A, Pacini G, et al. Visfatin response to glucose is reduced in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1889–1891. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haider DG, Holzer G, Schaller G, Weghuber D, Widhalm K, Wagner O, et al. The adipokine visfatin is markedly elevated in obese children. J.Pediatr.Gastroenterol.Nutr. 2006;43:548–549. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000235749.50820.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haider DG, Schaller G, Kapiotis S, Maier C, Luger A, Wolzt M. The release of the adipocytokine visfatin is regulated by glucose and insulin. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1909–1914. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haider DG, Schindler K, Schaller G, Prager G, Wolzt M, Ludvik B. Increased plasma visfatin concentrations in morbidly obese subjects are reduced after gastric banding. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2006;91:1578–1581. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hamilton BS, Paglia D, Kwan AY, Deitel M. Increased obese mRNA expression in omental fat cells from massively obese humans. Nat.Med. 1995;1:953–956. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hammarstedt A, Pihlajamaki J, Rotter S, V, Gogg S, Jansson PA, Laakso M, et al. Visfatin is an adipokine, but it is not regulated by thiazolidinediones. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2006;91:1181–1184. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haugen F, Ranheim T, Harsem NK, Lips E, Staff AC, Drevon CA. Increased plasma levels of adipokines in preeclampsia: relationship to placenta and adipose tissue gene expression. Am.J.Physiol Endocrinol.Metab. 2006;290:E326–E333. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00020.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hediger ML, Scholl TO, Ances IG, Belsky DH, Salmon RW. Rate and amount of weight gain during adolescent pregnancy: associations with maternal weight-for-height and birth weight. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 1990;52:793–799. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.5.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hendler I, Blackwell SC, Mehta SH, Whitty JE, Russell E, Sorokin Y, et al. The levels of leptin, adiponectin, and resistin in normal weight, overweight, and obese pregnant women with and without preeclampsia. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2005;193:979–983. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hickey CA, Cliver SP, McNeal SF, Hoffman HJ, Goldenberg RL. Prenatal weight gain patterns and birth weight among nonobese black and white women. Obstet.Gynecol. 1996;88:490–496. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Holcomb IN, Kabakoff RC, Chan B, Baker TW, Gurney A, Henzel W, et al. FIZZ1, a novel cysteine-rich secreted protein associated with pulmonary inflammation, defines a new gene family. EMBO J. 2000;19:4046–4055. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hotamisligil GS, Arner P, Caro JF, Atkinson RL, Spiegelman BM. Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. J.Clin.Invest. 1995;95:2409–2415. doi: 10.1172/JCI117936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.7678183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hu E, Liang P, Spiegelman BM. AdipoQ is a novel adipose-specific gene dysregulated in obesity. J.Biol.Chem. 1996;271:10697–10703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hug C, Lodish HF. Medicine. Visfatin: a new adipokine. Science. 2005;307:366–367. doi: 10.1126/science.1106933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iqbal J, Zaidi M. TNF regulates cellular NAD+ metabolism in primary macrophages. Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun. 2006;342:1312–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jia SH, Li Y, Parodo J, Kapus A, Fan L, Rotstein OD, et al. Pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor inhibits neutrophil apoptosis in experimental inflammation and clinical sepsis. J.Clin.Invest. 2004;113:1318–1327. doi: 10.1172/JCI19930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jian WX, Luo TH, Gu YY, Zhang HL, Zheng S, Dai M, et al. The visfatin gene is associated with glucose and lipid metabolism in a Chinese population. Diabet.Med. 2006;23:967–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jin H, Jiang B, Tang J, Lu W, Wang W, Zhou L, et al. Serum visfatin concentrations in obese adolescents and its correlation with age and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Diabetes Res.Clin.Pract. 2008;79:412–418. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jones BH, Standridge MK, Taylor JW, Moustaid N. Angiotensinogen gene expression in adipose tissue: analysis of obese models and hormonal and nutritional control. Am.J.Physiol. 1997;273:R236–R242. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.1.R236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocr.Rev. 2005;26:439–451. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K, Ueki K, Tobe K. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. J.Clin.Invest. 2006;116:1784–1792. doi: 10.1172/JCI29126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kafulafula GE, Moodley J, Ojwang PJ, Kagoro H. Leptin and pre-eclampsia in black African parturients. BJOG. 2002;109:1256–1261. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.02043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kahn BB, Flier JS. Obesity and insulin resistance. J.Clin.Invest. 2000;106:473–481. doi: 10.1172/JCI10842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kahn SE, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2006;444:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature05482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kajantie E, Kaaja R, Ylikorkala O, Andersson S, Laivuori H. Adiponectin concentrations in maternal serum: elevated in preeclampsia but unrelated to insulin sensitivity. J.Soc.Gynecol.Investig. 2005;12:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kalkhoff RK, Jacobson M, Lemper D. Progesterone, pregnancy and the augmented plasma insulin response. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 1970;31:24–28. doi: 10.1210/jcem-31-1-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kalkhoff RK, Richardson BL, Beck P. Relative effects of pregnancy, human placental lactogen and prednisolone on carbohydrate tolerance in normal and subclinical diabetic subjects. Diabetes. 1969;18:153–163. doi: 10.2337/diab.18.3.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Karlsson C, Lindell K, Ottosson M, Sjostrom L, Carlsson B, Carlsson LM. Human adipose tissue expresses angiotensinogen and enzymes required for its conversion to angiotensin II. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 1998;83:3925–3929. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.11.5276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kautzky-Willer A, Pacini G, Tura A, Bieglmayer C, Schneider B, Ludvik B, et al. Increased plasma leptin in gestational diabetes. Diabetologia. 2001;44:164–172. doi: 10.1007/s001250051595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kendal-Wright CE, Hubbard D, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Chronic Stretching of Amniotic Epithelial Cells Increases Pre-B Cell Colony-Enhancing Factor (PBEF/Visfatin) Expression and Protects Them from Apoptosis. Placenta. 2008;29:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kern PA, Saghizadeh M, Ong JM, Bosch RJ, Deem R, Simsolo RB. The expression of tumor necrosis factor in human adipose tissue. Regulation by obesity, weight loss, and relationship to lipoprotein lipase. J.Clin.Invest. 1995;95:2111–2119. doi: 10.1172/JCI117899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim KH, Lee K, Moon YS, Sul HS. A cysteine-rich adipose tissue-specific secretory factor inhibits adipocyte differentiation. J.Biol.Chem. 2001;276:11252–11256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kinalski M, Telejko B, Kuzmicki M, Kretowski A, Kinalska I. Tumor necrosis factor alpha system and plasma adiponectin concentration in women with gestational diabetes. Horm.Metab Res. 2005;37:450–454. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kirwan JP, Hauguel-De MS, Lepercq J, Challier JC, Huston-Presley L, Friedman JE, et al. TNF-alpha is a predictor of insulin resistance in human pregnancy. Diabetes. 2002;51:2207–2213. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Klok MD, Jakobsdottir S, Drent ML. The role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans: a review. Obes.Rev. 2007;8:21–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kocyigit Y, Atamer Y, Atamer A, Tuzcu A, Akkus Z. Changes in serum levels of leptin, cytokines and lipoprotein in pre-eclamptic and normotensive pregnant women. Gynecol.Endocrinol. 2004;19:267–273. doi: 10.1080/09513590400018108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Krzyzanowska K, Krugluger W, Mittermayer F, Rahman R, Haider D, Shnawa N, et al. Increased visfatin concentrations in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Clin.Sci.(Lond) 2006;110:605–609. doi: 10.1042/CS20050363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kuhl C. Aetiology of gestational diabetes. Baillieres Clin.Obstet.Gynaecol. 1991;5:279–292. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3552(05)80098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kuhl C. Glucose metabolism during and after pregnancy in normal and gestational diabetic women. 1. Influence of normal pregnancy on serum glucose and insulin concentration during basal fasting conditions and after a challenge with glucose. Acta Endocrinol.(Copenh) 1975;79:709–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kusminski CM, McTernan PG, Kumar S. Role of resistin in obesity, insulin resistance and Type II diabetes. Clin.Sci.(Lond) 2005;109:243–256. doi: 10.1042/CS20050078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Langer O, Anyaegbunam A, Brustman L, Guidetti D, Mazze R. Gestational diabetes: insulin requirements in pregnancy. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1987;157:669–675. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lewandowski KC, Stojanovic N, Press M, Tuck SM, Szosland K, Bienkiewicz M, et al. Elevated serum levels of visfatin in gestational diabetes: a comparative study across various degrees of glucose tolerance. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1033–1037. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Li L, Yang G, Li Q, Tang Y, Yang M, Yang H, et al. Changes and relations of circulating visfatin, apelin, and resistin levels in normal, impaired glucose tolerance, and type 2 diabetic subjects. Exp.Clin.Endocrinol.Diabetes. 2006;114:544–548. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-948309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lind T, Bell S, Gilmore E, Huisjes HJ, Schally AV. Insulin disappearance rate in pregnant and non-pregnant women, and in non-pregnant women given GHRIH. Eur.J.Clin.Invest. 1977;7:47–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1977.tb01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lonnqvist F, Arner P, Nordfors L, Schalling M. Overexpression of the obese (ob) gene in adipose tissue of human obese subjects. Nat.Med. 1995;1:950–953. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lopez-Bermejo A, Chico-Julia B, Fernandez-Balsells M, Recasens M, Esteve E, Casamitjana R, et al. Serum visfatin increases with progressive beta-cell deterioration. Diabetes. 2006;55:2871–2875. doi: 10.2337/db06-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lopez-Bermejo A, Fernandez-Real JM, Garrido E, Rovira R, Brichs R, Genaro P, et al. Maternal soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor type 2 (sTNFR2) and adiponectin are both related to blood pressure during gestation and infant's birthweight. Clin.Endocrinol.(Oxf) 2004;61:544–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lu D, Yang X, Wu Y, Wang H, Huang H, Dong M. Serum adiponectin, leptin and soluble leptin receptor in pre-eclampsia. Int.J.Gynaecol.Obstet. 2006;95:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.MacDougald OA, Hwang CS, Fan H, Lane MD. Regulated expression of the obese gene product (leptin) in white adipose tissue and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1995;92:9034–9037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Maeda K, Okubo K, Shimomura I, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Matsubara K. cDNA cloning and expression of a novel adipose specific collagen-like factor, apM1 (AdiPose Most abundant Gene transcript 1) Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun. 1996;221:286–289. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Malamitsi-Puchner A, Briana DD, Boutsikou M, Kouskouni E, Hassiakos D, Gourgiotis D. Perinatal circulating visfatin levels in intrauterine growth restriction. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1314–e1318. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Malamitsi-Puchner A, Briana DD, Gourgiotis D, Boutsikou M, Baka S, Hassiakos D. Blood visfatin concentrations in normal full-term pregnancies. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:526–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Manco M, Fernandez-Real JM, Equitani F, Vendrell J, Valera Mora ME, Nanni G, et al. Effect of massive weight loss on inflammatory adipocytokines and the innate immune system in morbidly obese women. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2007;92:483–490. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Marvin KW, Keelan JA, Eykholt RL, Sato TA, Mitchell MD. Use of cDNA arrays to generate differential expression profiles for inflammatory genes in human gestational membranes delivered at term and preterm. Mol.Hum.Reprod. 2002;8:399–408. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.4.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mastorakos G, Valsamakis G, Papatheodorou DC, Barlas I, Margeli A, Boutsiadis A, et al. The role of adipocytokines in insulin resistance in normal pregnancy: visfatin concentrations in early pregnancy predict insulin sensitivity. Clin.Chem. 2007;53:1477–1483. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.084731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Matsuzawa Y, Funahashi T, Kihara S, Shimomura I. Adiponectin and metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler.Thromb.Vasc.Biol. 2004;24:29–33. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000099786.99623.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mazurek T, Zhang L, Zalewski A, Mannion JD, Diehl JT, Arafat H, et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue is a source of inflammatory mediators. Circulation. 2003;108:2460–2466. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099542.57313.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.McCarthy JF, Misra DN, Roberts JM. Maternal plasma leptin is increased in preeclampsia and positively correlates with fetal cord concentration. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1999;180:731–736. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.McLachlan KA, O'Neal D, Jenkins A, Alford FP. Do adiponectin, TNFalpha, leptin and CRP relate to insulin resistance in pregnancy? Studies in women with and without gestational diabetes, during and after pregnancy. Diabetes Metab Res.Rev. 2006;22:131–138. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Melczer Z, Banhidy F, Csomor S, Kovacs M, Siklos P, Winkler G, et al. Role of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in insulin resistance during normal pregnancy. Eur.J.Obstet.Gynecol.Reprod.Biol. 2002;105:7–10. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(02)00108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Melczer Z, Banhidy F, Csomor S, Toth P, Kovacs M, Winkler G, et al. Influence of leptin and the TNF system on insulin resistance in pregnancy and their effect on anthropometric parameters of newborns. Acta Obstet.Gynecol.Scand. 2003;82:432–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mohamed-Ali V, Goodrick S, Rawesh A, Katz DR, Miles JM, Yudkin JS, et al. Subcutaneous adipose tissue releases interleukin-6, but not tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in vivo. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 1997;82:4196–4200. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Montague CT, Prins JB, Sanders L, Zhang J, Sewter CP, Digby J, et al. Depot-related gene expression in human subcutaneous and omental adipocytes. Diabetes. 1998;47:1384–1391. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.9.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Moschen AR, Kaser A, Enrich B, Mosheimer B, Theurl M, Niederegger H, et al. Visfatin, an adipocytokine with proinflammatory and immunomodulating properties. J.Immunol. 2007;178:1748–1758. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Nakano Y, Tobe T, Choi-Miura NH, Mazda T, Tomita M. Isolation and characterization of GBP28, a novel gelatin-binding protein purified from human plasma. J.Biochem.(Tokyo) 1996;120:803–812. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Naruse K, Yamasaki M, Umekage H, Sado T, Sakamoto Y, Morikawa H. Peripheral blood concentrations of adiponectin, an adipocyte-specific plasma protein, in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. J.Reprod.Immunol. 2005;65:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Nemeth E, Millar LK, Bryant-Greenwood G. Fetal membrane distention: II. Differentially expressed genes regulated by acute distention in vitro. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2000;182:60–67. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70491-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Nemeth E, Tashima LS, Yu Z, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Fetal membrane distention: I. Differentially expressed genes regulated by acute distention in amniotic epithelial (WISH) cells. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2000;182:50–59. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70490-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Nien JK, Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Erez O, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, et al. Plasma adiponectin concentrations in non-pregnant, normal and overweight pregnant women. J.Perinat.Med. 2007;35:522–531. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2007.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Nien JK, Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Erez O, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, et al. Adiponectin in severe preeclampsia. J.Perinat.Med. 2007;35:503–512. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2007.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.nim-Nyame N, Sooranna SR, Steer PJ, Johnson MR. Longitudinal analysis of maternal plasma leptin concentrations during normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Hum.Reprod. 2000;15:2033–2036. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.9.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ning Y, Williams MA, Muy-Rivera M, Leisenring WM, Luthy DA. Relationship of maternal plasma leptin and risk of pre-eclampsia: a prospective study. J.Matern.Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;15:186–192. doi: 10.1080/14767050410001668293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Nowell MA, Richards PJ, Fielding CA, Ognjanovic S, Topley N, Williams AS, et al. Regulation of pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor by STAT-3-dependent interleukin-6 trans-signaling: implications in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2084–2095. doi: 10.1002/art.21942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ognjanovic S, Bao S, Yamamoto SY, Garibay-Tupas J, Samal B, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Genomic organization of the gene coding for human pre-B-cell colony enhancing factor and expression in human fetal membranes. J.Mol.Endocrinol. 2001;26:107–117. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0260107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ognjanovic S, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor, a novel cytokine of human fetal membranes. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2002;187:1051–1058. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.126295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ognjanovic S, Ku TL, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor is a secreted cytokine-like protein from the human amniotic epithelium. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2005;193:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ognjanovic S, Tashima LS, Bryant-Greenwood GD. The effects of pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor on the human fetal membranes by microarray analysis. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2003;189:1187–1195. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00591-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Okamoto Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Nishida M, Arita Y, Kumada M, et al. Adiponectin reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2002;106:2767–2770. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000042707.50032.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Okamoto Y, et al. Novel modulator for endothelial adhesion molecules: adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin. Circulation. 1999;100:2473–2476. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.25.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Nishida M, Matsuyama A, Okamoto Y, et al. Adipocyte-derived plasma protein, adiponectin, suppresses lipid accumulation and class A scavenger receptor expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Circulation. 2001;103:1057–1063. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.8.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Nakamura T, Nishida M, Kumada M, et al. Reciprocal association of C-reactive protein with adiponectin in blood stream and adipose tissue. Circulation. 2003;107:671–674. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055188.83694.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Ouyang Y, Chen H, Chen H. Reduced plasma adiponectin and elevated leptin in pre-eclampsia. Int.J.Gynaecol.Obstet. 2007;98:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Pagano C, Pilon C, Olivieri M, Mason P, Fabris R, Serra R, et al. Reduced plasma visfatin/pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor in obesity is not related to insulin resistance in humans. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2006;91:3165–3170. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Phelps RL, Metzger BE, Freinkel N. Carbohydrate metabolism in pregnancy. XVII. Diurnal profiles of plasma glucose, insulin, free fatty acids, triglycerides, cholesterol, and individual amino acids in late normal pregnancy. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1981;140:730–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Polderman KH, Gooren LJ, Asscheman H, Bakker A, Heine RJ. Induction of insulin resistance by androgens and estrogens. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 1994;79:265–271. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.1.8027240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Purohit A, Ghilchik MW, Duncan L, Wang DY, Singh A, Walker MM, et al. Aromatase activity and interleukin-6 production by normal and malignant breast tissues. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 1995;80:3052–3058. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.10.7559896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Qiu C, Sorensen TK, Luthy DA, Williams MA. A prospective study of maternal serum C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Paediatr.Perinat.Epidemiol. 2004;18:377–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Qiu C, Williams MA, Vadachkoria S, Frederick IO, Luthy DA. Increased maternal plasma leptin in early pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet.Gynecol. 2004;103:519–525. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000113621.53602.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Rajala MW, Scherer PE. Minireview: The adipocyte--at the crossroads of energy homeostasis, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3765–3773. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Ramsay JE, Jamieson N, Greer IA, Sattar N. Paradoxical elevation in adiponectin concentrations in women with preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2003;42:891–894. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000095981.92542.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Ranheim T, Haugen F, Staff AC, Braekke K, Harsem NK, Drevon CA. Adiponectin is reduced in gestational diabetes mellitus in normal weight women. Acta Obstet.Gynecol.Scand. 2004;83:341–347. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Reece EA, Homko C, Wiznitzer A. Metabolic changes in diabetic and nondiabetic subjects during pregnancy. Obstet.Gynecol.Surv. 1994;49:64–71. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199401000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Retnakaran R, Hanley AJ, Raif N, Connelly PW, Sermer M, Zinman B. Reduced adiponectin concentration in women with gestational diabetes: a potential factor in progression to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:799–800. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.3.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Revollo JR, Korner A, Mills KF, Satoh A, Wang T, Garten A, et al. Nampt/PBEF/Visfatin regulates insulin secretion in beta cells as a systemic NAD biosynthetic enzyme. Cell Metab. 2007;6:363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Ronti T, Lupattelli G, Mannarino E. The endocrine function of adipose tissue: an update. Clin.Endocrinol.(Oxf) 2006;64:355–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. Adipocytes as regulators of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Nature. 2006;444:847–853. doi: 10.1038/nature05483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Rosso P. A new chart to monitor weight gain during pregnancy. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 1985;41:644–652. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/41.3.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Ryan EA, Enns L. Role of gestational hormones in the induction of insulin resistance. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 1988;67:341–347. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-2-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Ryan EA, O'Sullivan MJ, Skyler JS. Insulin action during pregnancy. Studies with the euglycemic clamp technique. Diabetes. 1985;34:380–389. doi: 10.2337/diab.34.4.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Samaan N, Yen SC, Gonzalez D, Pearson OH. Metabolic effects of placental lactogen (HPL) in man. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 1968;28:485–491. doi: 10.1210/jcem-28-4-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Samal B, Sun Y, Stearns G, Xie C, Suggs S, McNiece I. Cloning and characterization of the cDNA encoding a novel human pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor. Mol.Cell Biol. 1994;14:1431–1437. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Sandeep S, Velmurugan K, Deepa R, Mohan V. Serum visfatin in relation to visceral fat, obesity, and type 2 diabetes mellitus in Asian Indians. Metabolism. 2007;56:565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Sartipy P, Loskutoff DJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in obesity and insulin resistance. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2003;100:7265–7270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Scherer PE, Williams S, Fogliano M, Baldini G, Lodish HF. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. J.Biol.Chem. 1995;270:26746–26749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Sekiya N, Anai T, Matsubara M, Miyazaki F. Maternal weight gain rate in the second trimester are associated with birth weight and length of gestation. Gynecol.Obstet.Invest. 2007;63:45–48. doi: 10.1159/000095286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Sethi JK, Vidal-Puig A. Visfatin: the missing link between intra-abdominal obesity and diabetes? Trends Mol.Med. 2005;11:344–347. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Sharma A, Satyam A, Sharma JB. Leptin, IL-10 and inflammatory markers (TNF-alpha, IL-6 and IL-8) in pre-eclamptic, normotensive pregnant and healthy non-pregnant women. Am.J.Reprod.Immunol. 2007;58:21–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Shea J, Randell E, Vasdev S, Wang PP, Roebothan B, Sun G. Serum retinol-binding protein 4 concentrations in response to short-term overfeeding in normal-weight, overweight, and obese men. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 2007;86:1310–1315. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Shimomura I, Funahashi T, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Kotani K, Nakamura T, et al. Enhanced expression of PAI-1 in visceral fat: possible contributor to vascular disease in obesity. Nat.Med. 1996;2:800–803. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Silha JV, Krsek M, Skrha JV, Sucharda P, Nyomba BL, Murphy LJ. Plasma resistin, adiponectin and leptin levels in lean and obese subjects: correlations with insulin resistance. Eur.J.Endocrinol. 2003;149:331–335. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1490331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Sivan E, Chen X, Homko CJ, Reece EA, Boden G. Longitudinal study of carbohydrate metabolism in healthy obese pregnant women. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1470–1475. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.9.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.SPELLACY WN, GOETZ FC, GREENBERG BZ, ELLS J. PLASMA INSULIN IN NORMAL "EARLY" PREGNANCY. Obstet.Gynecol. 1965;25:862–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, Brown EJ, Banerjee RR, Wright CM, et al. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature. 2001;409:307–312. doi: 10.1038/35053000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Steppan CM, Lazar MA. Resistin and obesity-associated insulin resistance. Trends Endocrinol.Metab. 2002;13:18–23. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Suwaki N, Masuyama H, Nakatsukasa H, Masumoto A, Sumida Y, Takamoto N, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia and circulating angiogenic factors in overweight patients complicated with pre-eclampsia. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2006;195:1687–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Tan BK, Chen J, Digby JE, Keay SD, Kennedy CR, Randeva HS. Increased visfatin messenger ribonucleic acid and protein levels in adipose tissue and adipocytes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: parallel increase in plasma visfatin. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2006;91:5022–5028. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Tanaka M, Nozaki M, Fukuhara A, Segawa K, Aoki N, Matsuda M, et al. Visfatin is released from 3T3-L1 adipocytes via a non-classical pathway. Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun. 2007;359:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Teppa RJ, Ness RB, Crombleholme WR, Roberts JM. Free leptin is increased in normal pregnancy and further increased in preeclampsia. Metabolism. 2000;49:1043–1048. doi: 10.1053/meta.2000.7707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Thyfault JP, Hedberg EM, Anchan RM, Thorne OP, Isler CM, Newton ER, et al. Gestational diabetes is associated with depressed adiponectin levels. J.Soc.Gynecol.Investig. 2005;12:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Adipocytokines: mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat.Rev.Immunol. 2006;6:772–783. doi: 10.1038/nri1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Trayhurn P. Endocrine and signalling role of adipose tissue: new perspectives on fat. Acta Physiol Scand. 2005;184:285–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2005.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Trayhurn P, Wood IS. Adipokines: inflammation and the pleiotropic role of white adipose tissue. Br.J.Nutr. 2004;92:347–355. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Tsai PJ, Yu CH, Hsu SP, Lee YH, Huang IT, Ho SC, et al. Maternal plasma adiponectin concentrations at 24 to 31 weeks of gestation: negative association with gestational diabetes mellitus. Nutrition. 2005;21:1095–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Unger RH. Hyperleptinemia: protecting the heart from lipid overload. Hypertension. 2005;45:1031–1034. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000165683.09053.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Uysal KT, Wiesbrock SM, Marino MW, Hotamisligil GS. Protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking TNF-alpha function. Nature. 1997;389:610–614. doi: 10.1038/39335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Vidal H. Gene expression in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues. Ann.Med. 2001;33:547–555. doi: 10.3109/07853890108995965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Wang B, Jenkins JR, Trayhurn P. Expression and secretion of inflammation-related adipokines by human adipocytes differentiated in culture: integrated response to TNF-alpha. Am.J.Physiol Endocrinol.Metab. 2005;288:E731–E740. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00475.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Williams CM, Pipe NG, Coltart TM. A longitudinal study of adipose tissue glucose utilization during pregnancy and the puerperium in normal subjects. Hum.Nutr.Clin.Nutr. 1986;40:15–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Williams MA, Qiu C, Muy-Rivera M, Vadachkoria S, Song T, Luthy DA. Plasma adiponectin concentrations in early pregnancy and subsequent risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2004;89:2306–2311. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Winkler G, Cseh K, Baranyi E, Melczer Z, Speer G, Hajos P, et al. Tumor necrosis factor system in insulin resistance in gestational diabetes. Diabetes Res.Clin.Pract. 2002;56:93–99. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(01)00355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Wolf M, Sandler L, Hsu K, Vossen-Smirnakis K, Ecker JL, Thadhani R. First-trimester C-reactive protein and subsequent gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:819–24. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Worda C, Leipold H, Gruber C, Kautzky-Willer A, Knofler M, Bancher-Todesca D. Decreased plasma adiponectin concentrations in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2004;191:2120–2124. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198.Xie H, Tang SY, Luo XH, Huang J, Cui RR, Yuan LQ, et al. Insulin-like effects of visfatin on human osteoblasts. Calcif.Tissue Int. 2007;80:201–210. doi: 10.1007/s00223-006-0155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.Yang WS, Lee WJ, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Matsuzawa Y, Chao CL, et al. Weight reduction increases plasma levels of an adipose-derived anti-inflammatory protein, adiponectin. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2001;86:3815–3819. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200.Ye SQ, Simon BA, Maloney JP, Zambelli-Weiner A, Gao L, Grant A, et al. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor as a potential novel biomarker in acute lung injury. Am.J.Respir.Crit Care Med. 2005;171:361–370. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-563OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 201.Ye SQ, Zhang LQ, Adyshev D, Usatyuk PV, Garcia AN, Lavoie TL, et al. Pre-B-cell-colony-enhancing factor is critically involved in thrombin-induced lung endothelial cell barrier dysregulation. Microvasc.Res. 2005;70:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 202.Zahorska-Markiewicz B, Olszanecka-Glinianowicz M, Janowska J, Kocelak P, Semik-Grabarczyk E, Holecki M, et al. Serum concentration of visfatin in obese women. Metabolism. 2007;56:1131–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 203.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372:425–432. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]