Abstract

Genetic analysis of Bacteroides fragilis (BF) is hindered due to the lack of efficient transposon mutagenesis methods. Here we describe a simple method for transposon mutagenesis using EZ∷TN5, a commercially available system that we optimized for use in BF638R. The modified EZ∷TN5 transposon contains an E. coli conditional origin of replication, a kanamycin resistance gene for E. coli, an erythromycin resistance gene for BF and 19 basepair transposase recognition sequences on either ends. Electroporation of the transposome (transposon-transposase complex) into BF638R yielded 3.2± 0.35×103 CFU/μg of transposon DNA. Modification of the transposon by the BF638R restriction/modification system increased transposition efficiency 6-fold. Electroporation of the EZ∷TN5 transposome results in a single copy insertion of the transposon evenly distributed across the genome of BF638R and can be used to construct a BF638R transposon library. The transposon was also effective in mutating a BF clinical isolate and a strain of the related species, B. thetaiotaomicron. The EZ∷TN5 based mutagenesis described here is more efficient than other transposon mutagenesis approaches previously reported for BF.

Keywords: Bacteroides fragilis, transposon mutagenesis, mutant library

INTRODUCTION

Bacteroides fragilis is a Gram-negative, anaerobic bacterium associated with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of animals and humans (Gilmore & Ferretti, 2003) and is the major Bacteroides species isolated from human infections (80%) (Bennion et al., 1990, Wexler et al., 1998, Wexler, 2007). As a commensal, it hydrolyzes complex polysaccharides and produces volatile fatty acids used by the host as source of energy (Wexler, 2007). When BF escapes the GI tract, it can cause serious infections (Gilmore & Ferretti, 2003).

Investigation of the BF genetic makeup and its regulatory processes will aid in understanding how BF can evolve from a benign commensal to a multidrug-resistant pathogen. The function of most genes cannot be determined from primary sequence analysis alone (Cerdeno-Tarraga et al., 2005, Patrick et al., 2010) and the creation of mutants (Mazurkiewicz et al., 2006) is a useful tool for deducing gene function. Since transposons are known for their random insertion into the genome, they have been widely used for construction of mutant libraries (Gallagher et al., 2007, Jacobs et al., 2003).

To date, two transposons (Tn4351 and Tn4400) have been used for generation of random mutations in BF. However, each has certain drawbacks. A Tn4351 transposon derivative (used for BF, B. thetaiotaomicron and related bacteria) may integrate into the genomic DNA along with its vector, thereby complicating the molecular characterization of the mutated gene (Shoemaker et al., 1986, Chen et al., 2000a). In addition, mutants generated by Tn4351 can contain multiple Tn4351 insertions which further hinder characterization of the mutants (Shoemaker et al., 1986). A modified Tn4400 transposon vector, pYT646B (Tang & Malamy, 2000) generates mutants by inverse transposition; however, this transposon can also incorporate at multiple positions in a single mutant, potentially complicating further analysis (Chen et al., 2000b, Tang & Malamy, 2000).

Ease of identifying the disrupted gene is also an important factor in the utility of these transposons. Tn4400 has a HindIII site within the transposon sequence so that sequences flanking IS4400R (right inverted repeat) can be identified by self-ligation of HindIII-digested genomic DNA of the mutant and subsequent rescue cloning and sequencing. However, retrieving the gene fragment adjacent to the IS4400L (left inverted repeat) is more difficult due to the lack of appropriate restriction enzymes (Tang & Malamy, 2000).

Due to the restrictions and drawbacks in the existing systems, we sought to develop an alternative, efficient and reliable transposon tool for BF that would allow easy downstream identification and sequencing of the mutated gene. The EZ∷TN5 transposome (EPICENTRE® Biotechnologies, Madison USA) is an alternative genetic tool for transposon mutant library construction. The EZ∷TN5 transposome can be generated in vitro using purified EZ∷TN5 transposase and a DNA fragment (usually antibiotic cassette) flanked by inverted repeats. This system provides an efficient and reliable method of inserting transposon DNA into the genome of many different microorganisms (www.epibio.com).

This study reports the development of a simple EZ∷TN5-based approach for transposon mutagenesis in BF. Mutants generated by this method contain a single mutation and the mutated gene can be easily identified by either rescue cloning or by semi-random primer (SRP) analysis. This improved mutagenesis method will optimize the creation of transposon mutant libraries for use in ascribing function to specific genes in BF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions

All strains were grown as described (Pumbwe et al., 2005). E. coli Top10 (Invitrogen, NY, USA) was used as the host for cloning. Ampicillin (Amp) (100μg/ml), erythromycin (Erm)(10μg/ml), kanamycin (40μg/ml) and gentamycin (40μg/ml) were used for selection as indicated.

DNA analysis

DNA preparation, restriction digestions, gel electrophoresis and analysis were done as previously described (Pumbwe et al., 2006b). Sequencing was done by Laragen (Culver City, CA).

EZ∷TN5 transposon vector construction

The EZ∷Tn5 carrying plasmid pMOD-3 <R6Kγori/MCS> (EPICENTRE® Biotechnologies, Madison USA.) was modified for use in BF638R.

Introduction of ermF into pMOD-3 <R6Kγori/MCS>

The erythromycin resistant gene (ermF) along with its promoter was PCR amplified with ermF F SacI and ermF R SacI primers (Table 1) using the Bacteroides shuttle vector pFD288 as template DNA (Smith et al., 1995) and ligated into pGEM®-T Easy. E. coli Top 10 chemically competent cells were transformed with the ligation mix and transformants selected on LB-Amp agar plate, yielding plasmid pT-ermF-4. The ermF was retrieved from pT-ermF-4 by Sac I digestion and ligated into Sac I-digested pMOD-3 <R6Kγori/MCS>. E. coli Top10 competent cells were transformed with the ligation mix and transformants selected on LB-Amp agar plate, yielding pYV01.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | 301 |

|---|---|---|

| ermF F SacI | GATATCGAGCTCCCTGTAAACAGTGC | 302 |

| ermF R SacI | GATATCGAGCTCAATTTGCCAGCCGTTATG | 303 |

| Km F EcoRV | GATATCGAGCTCGTGGAACGAAAACTCACGTTAAGG | 304 |

| Km R EcoRV | GATATCGAGCTCCATTCAAATATGTATCCGCTC | 305 |

| pFKRepAF | AGATCTGATATCCTTCAATACCTCTCTGGATGGC | 306 |

| pFKRepAR | AGATCTCCCGGGCTGATACCAATATCAAATCTCC | 307 |

| EzTnSeq3R | CGAGCCAATATGCGAGAACACCCGAGAA | 308 |

| EzTnSeqFP | GCCATGAGAGCTTAGTACGTTAGC | 309 |

| SRP1 | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACNNNNNNNNNNGATAT | 310 |

| EnTnSeqNIR | CGATTTTCAGGAAAAGTCAGGTCAG | 311 |

| SRP2 | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTAC | 312 |

| EzTnSeqN2R | GTCTCCAAGTCAATGGTTAAACTG | 313 |

| SRP3 | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACNNNNNNNNNNACGCC | 314 |

| ermF-BamHI-F | TGTAAGAAGGGATCCATGACAAAAAAGAAATTGCCC | 315 |

| ermF-BamHI-R | ACCCGACGGATCCCTACGAAGGATGAAATTTTTCAGGG | 316 |

Introduction of the kanamycin resistance gene (km) into pYV01

The kanamycin gene (km) along with its promoter was PCR amplified with Km F EcoRV and Km R EcoRV primers (Table 1) using pET-27B(+) as template DNA. The amplified PCR product (0.95 kb) was purified and ligated into pGEM®-T Easy. E. coli Top 10 cells were transformed with the ligation mix and transformants were selected on LB-Km agar plate, yielding plasmid pT-Km-2. The km gene was retrieved from pT-Km-2 by EcoRV digestion and ligated into SmaI –digested pYV01. E. coli Top10 competent cells were transformed with the ligation product and transformants select on LB-Km agar plate yielding plasmid pYV02; this plasmid was used for transposome preparation (see below).

Restriction/modification (R/M) of pYV02 in BF638R

pYV02 was passed through BF638R so that the transposon would be properly modified by the host methylation system to avoid subsequent degradation. For this purpose, repA (for replication in BF) was PCR-amplified using primers pFKRepAF and pFKRepAR using pKF12 as template DNA (Haggoud et al., 1995). The amplified PCR product (1.68 kb) was purified, digested with SmaI/Eco RV and ligated into SmaI site of pYV02. BF638R was transformed with the ligation mix by electroporation and transformants selected on BHI-Erm agar plate yielding pYV03.

EZ∷TN5 transposome preparation and transposon mutagenesis of BF638R

Transposomes were prepared according to manufacturers’ protocol with the following modifications. EZ∷TN5 transposon DNA was retrieved from either pYV02 or pYV03 (BF- R/M vector) following PvuII digestion. The resulting 2.6 kb fragment was gel-purified and column eluted (Qiaquick Gel Extraction Kit, QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, CA) with TE buffer (10mM Tris-HCL [pH7.5], 1mM EDTA). For transposome preparation, 2 μl of EZ∷TN5 transposon DNA (100ng/μl) was mixed with 4 U (4μl) of En-Tn5™ transposase (EPICENTRE® Biotechnologies, Madison, WI) plus 2μl of glycerol (100%) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The resulting transposon-EZ∷TN5 transposase mixture (transposome) was stored at −20°C and used for mutagenesis of BF.

BF electrocompetent cell preparation

A single colony of BF638R grown on BHI was inoculated in 5 ml BHI broth and incubated anaerobically overnight (16h) at 37°C. Cultures were diluted (1:100) in 100ml BHI broth and allowed to grow to an OD600 of 0.3-0.4. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 5020 g for 5 min and washed 5 times with 50 ml of ice-cold 10% glycerol. Cells were finally suspended in 1 ml of 10% glycerol and 100 μl aliquots were used for electroporation.

Electroporation conditions

Transposome (2μl) was mixed with 100 μl BF638R competent cells in a 0.2 cm electroporation cuvette and incubated on ice for 30 min. Electroporation was performed using a BioRad Gene Pulser™ (200 Ohms, 25μF and 2.5 kV.) Following electroporation, 900μl of pre-reduced BHI broth was added and the mixture incubated anaerobically for 3h at 37°C. The cells were then plated on BHI-Erm agar plate (to select for transposon mutants) and incubated anaerobically for 3 days at 37°C.

Southern blot analysis

The probe, ermF, was PCR amplified using ermF-BamHI-F and ermF-BamHI-R primers with pFD288 as template DNA. Biotin-16-dUTP (Roche Applied Bioscience, Indianapolis, IN) was incorporated into the probe during PCR amplification. Genomic DNA was isolated using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Genomic DNA (2mg) was digested overnight with Bgl II, electrophoresed (0.8% agarose) and transferred to Nytran SuperCharge Nylon membrane (Whatman, Piscataway, N.J.) using the Turboblotter Rapid Downward Transfer Systems (Whatman, Piscataway, N.J). DNA was cross-linked to the membrane by baking at 80°C for 2 hours. Hybridization and detection of probe was done with the biotin Chromogenic kit (Fermantas, Glen Burnie, Md.).

Identification of transposon-disrupted gene by rescue cloning

Genomic DNA was prepared from transposon mutants and digested with BglII (any enzyme that does not cut within the transposon could be used). Subsequently, the digested DNA was purified, self-ligated with T4 DNA ligase and introduced into electrocompetent EC100D pir- 116 E. coli (EPICENTRE® Biotechnologies, Madison WI) by electroporation. The circularized fragments containing the transposon replicate as plasmids and the transformants were recovered on LB agar plates containing kanamycin (LB-Km). Transposon junction plasmids were isolated from selected transformants and sequenced using transposon specific outward primers EZTNSeq3R and EZTNSeqFP (Table 1) which anneal to ≤100 bp upstream of the mosaic end left (MEL) and the mosaic end right (MER), respectively. Sequences were then compared to the protein sequence database (GenBank) using the BlastX algorithm. For each mutant, the junction between the transposon sequence (the Tn5 inverted repeat sequence ending with CTGTCTCTTATACACATCT or AGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG) and the genomic DNA sequence as well as the 9-bp target duplication (a characteristic of Tn5 insertions) were identified.

Identification of the transposon-disrupted gene by nested PCR using semi-random primers (SRP)

The SRP-PCR was developed as described by Chen et al. (2000b). The first round of PCR was performed using OneTaq™ Hot Start 2X master mix (New England Biolabs MA USA.) with SRP1 and EnTnSeqN1R (transposon specific) primers and template DNA from the mutant. The first round PCR conditions were 10 min at 95°C, 6 cycles of 30s at 95°C, 30s at 30°C, and 1.5 min at 68°C with 5s increments per cycle; 30 cycles of 30s at 95°C, 30s at 45°C, and 2 min at 68°C with 5s increments per cycle; and 5 min at 68°C. One microliter of the first round PCR product was used as the template in the second round PCR with primers SRP2 and EzTnSeqN2R with. The product of second round PCR was column purified and sequenced with primer EzTnSeq3R. Sequences which contained the MEL sequence were considered bona fide transposon-disrupted genes. SRP3 was used as an alternative to SRP1 in the first round PCR in cases where SRP1 did not yield the desired PCR product.

RESULTS

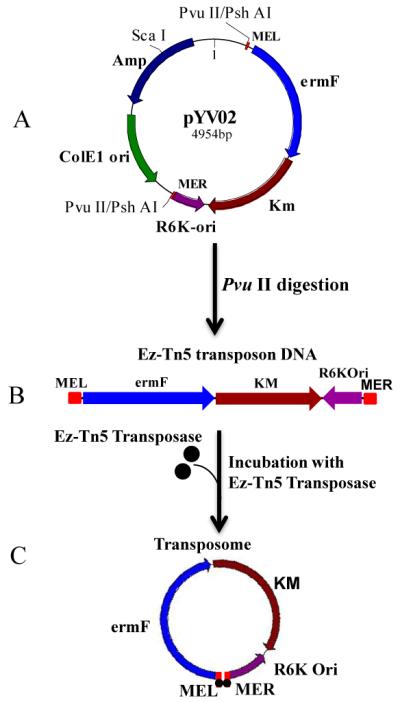

Transposon mutagenesis of BF638R using modified EZ∷TN5 transposome

The transposon vector pYV02 (Fig. 1A) was constructed as described in Materials and Methods. Digestion of pYV02 with PvuII yielded a transposon that contained the E. coli conditional origin of replication (R6K-ori), the kanamycin resistance gene (km), ermF (erythromycin resistance gene for selection of transposon insertion in BF) and 19 basepair transposase recognition sequences (mosaic ends, ME) on either ends (Fig. 1B). R6K-ori and km enable rescue of the transposon with the surrounding mutated gene sequence in E. coli. Transposase was added to the customized EZ∷TN5 product forming the transposome which was then introduced into BF638R by electroporation (Fig. C). The transformants were selected on BHI/Erm. About twenty randomly selected transformants were tested for the presence of ermF; all potential mutants showed the expected PCR product (1.2 kb band) (Data not shown). The efficiency of EZ∷TN5 transposon insertion in BF638R was 3.2± 0.35 × 103 /μg of transposon DNA.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of EZ∷TN5 transposome preparation. A) pYV02, the transposon carrying plasmid: mosaic end left (MEL), erythromycin resistance gene (ermF), kanamycin resistance gene (Km), E. coli conditional origin of replication (R6Kori), mosaic end right (MER), E. coli origin of replication (ColE1 ori), ampicillin resistance gene (amp). B) Digestion of pYV02 with PvuII/PshAI which cuts near mosaic ends yield the EZ∷TN5 transposon. C) Incubation of transposon with EZ∷TN5 transposase (•) yields the transposome (which is then used for electroporation).

Passage of the transposon DNA through BF638R increases efficiency of transposon mutagenesis

The BF genome contains extensive endogenous R/M systems that protect host DNA by recognizing and cleaving foreign DNA (Cerdeno-Tarraga et al., 2005, Patrick et al., 2010). Since the transposon DNA was prepared from E. coli, the BF638R R/M system might degrade the transposon DNA which would impair transposition efficiency (Salyers et al., 2000). Therefore, pYV02 was electroporated into BF638R so that it would be restriction modified by the BF638R system in order to increase transposon efficiency, as described in Materials and Methods. The transposomes were then prepared from pYV03 and electroporated to BF638R. The BF638R modified transposon was nearly 6-times more efficient (1.9±0.3×104) than before modification, confirming that bypassing the host R/M system can increase transposon efficiency.

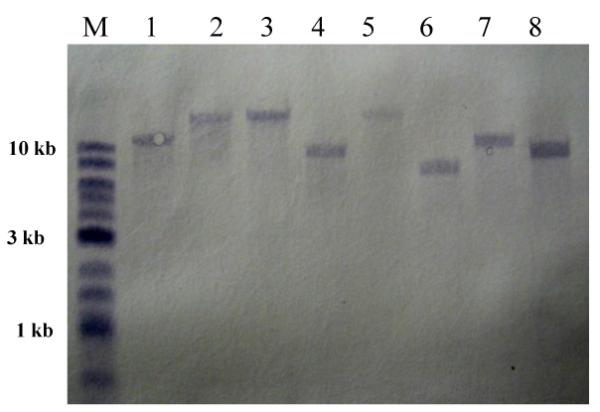

Southern hybridization confirmed that EZ∷TN5 delivered a single copy of transposon per genome

Chromosomal DNA was prepared from eight randomly selected mutants, digested with BglII (which has no recognition site within the ermF gene). Following Southern hybridization using a biotin-labeled ermF probe (Fig. 2), all strains contained only a single hybridizing DNA fragment, demonstrating that each mutant contain only single copy of ermF. This property of the transposon is very important as it enables the study of the effect of a single gene disruption in a given mutant. This modified EZ∷TN5 system is superior to other transposon systems described for BF in consistently delivering only a single copy per chromosome.

Figure 2.

Transposition of transposome in BF638R. Southern hybridization: DNA from transposon mutant was digested with BglII and transferred to a nylon membrane. The ermF gene present on chromosomal DNA was probed with the biotin Chromogenic kit. Lane 1. M Biotinylated 2-Log DNA Ladder, Lanes 2-7 are EZY mutants.

Modified EZ∷TN transposon inserts properly into the BF638R chromosome

Externally added DNA may undergo illegitimate recombination with the bacterial chromosome (Desomer et al., 1991, Kalpana et al., 1991, Chua et al., 2000). To confirm that this was not occurring, we rescued the genomic region flanking the EZ∷TN transposon from the mutants and looked for a 9-bp target site duplication in the mutant DNA. Analysis of the DNA sequence flanking the EZ∷TN transposon at MEL and MER revealed that each insertion was flanked by the 9-bp duplication characteristic of the Tn5 insertion (Table 2) (Berg & Berg, 1983), confirming that that the antibiotic-resistant transconjugants arose by transposition of the EZ∷TN transposon into the host chromosome.

Table 2.

Confirmation of transposon insertion in BF638R transposon mutants: the mutated genes in eight randomly selected mutants were retrieved by rescue cloning and sequenced with forward (EzTnSeqFP) and reverse ( EzTnSeq3R) primers that read fromMER and MEL respectively. The nine nucleotides next to the mosaic ends are shown.

| Mutant name | 9bp duplication |

|---|---|

| EZY4 | MER: ATATAAGAG |

| MEL: CTCTTATAT | |

| EZY5 | MER: GGTTAATGG |

| MEL: CCATTAACC | |

| EZY6 | MER: CTCCAGAAC |

| MEL: GTTCTGGAG | |

| EZY7 | MER: GGGTTAAGT |

| MEL: ACTTAACCC | |

| EZY8 | MER: GTACGGAGC |

| MEL: GCTCCGTAC | |

| EZY9 | MER: GTTCTCGGC |

| MEL: GCCGAGAAC | |

| EZY10 | MER: GGGCTACAC |

| MEL: GTGTAGCCC | |

| EZY11 | MER: GGATCGTAT |

| MEL: ATACGATCC |

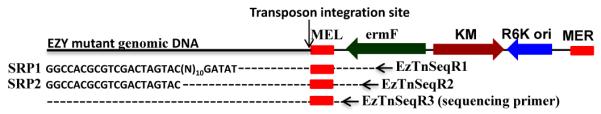

Modified EZ∷TN can be used to construct a mutant library in BF638R and the resultant mutants can be rapidly identified by SRP-PCR

The library was screened for auxotrophic mutants in order to demonstrate the usefulness of the modified EZ∷TN 5 transposome in mutant library construction. Five hundred BF638R transposon mutants were replica plated onto minimal media with or without Casamino acids (0.5% wt/vol) (Baughn & Malamy, 2002). One of 500 transposon mutants screened failed to grow on minimal medium without Casamino acids, suggesting that a gene in an amino acid biosynthesis pathway was disrupted (Mutant EZY6).

The disrupted gene in the auxotrophic mutant was identified by the SRP-PCR (Fig. 3). The identification of the 19 bp inverted repeat on the amplified PCR products confirmed that isolated auxotrophic mutant was a “true” transposon insertant. We also identified the transposon disrupted gene using the alternative rescue cloning method described in Materials and Methods. Both the methods independently indicated that EZY6 had a mutation in argC (acetylglutamyl phosphate reductase, BF638R_0529), a gene in the arginine biosynthesis pathway. We found that the SRP-PCR technique was faster and simpler than the rescue cloning method for identifying the disrupted gene.

Figure 3.

Identification of mutated gene in BF638R. A) Schematic representation of SRP-PCR. The first round PCR was done with SRP1 and EzTnSeqR1 with template DNA from the mutant. The second round PCR was done with SRP2 and EzTnSeqR2 primers with 1μl template from the first round PCR. The product of second round PCR was column purified and sequenced with the EzTnSeqR3 primer.

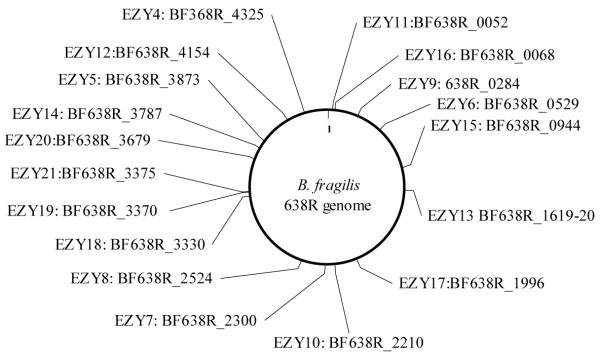

Selected mutants which grew slowly on minimal medium were also chosen for further study. The mutated genes were identified by SRP-PCR and results are presented in Fig. 4. Mutants had transposon insertions in two-component regulators (EZY7), cell division proteins (EZY11), aminotransferase (EZY17), GMP biosynthesis pathway (EZY19), transport related proteins (EZY21) and various other genes. The disrupted genes were scattered throughout the genome of BF638R (Fig.4), confirming that the custom EZ∷TN5 transposome described here can randomly insert the transposon into the B. fragilis chromosome.

Figure 4.

Transposon mutants of BF638R. There are 4,535 genes in the BF638R genome. Twenty random transposon mutants were identified by SRP-PCR and named EZY-4 thru 21. The locus tag of the gene in which the transposon was inserted is shown.

Modified EZ∷TN5 transposome can be used to create mutants in BF clinical isolates as well as in the related species, B. thetaiotaomicron

The utility of the customized EZ∷TN5 transposon for generating mutants in BF 9343 (ATCC 25285), BF clinical isolates and B. thetaiotaomicron (Pumbwe et al., 2006a) was examined. The transposome was prepared from BF638R- modified pYV03. The efficiencies of the transposition in the clinical strain BF14412 and B. thetaiotaomicron were 3.6±0.67×103 and 6.3±1.2×103, respectively, indicating that the system may be useful for some clinical strains of BF as well as B. thetaiotaomicron. No mutants were generated in BF 9343 or the clinical isolate BF7320. It is possible that pYV03 DNA modified by the BF638R R/M system was recognized as foreign and cleaved by the resident type I and II R/M system of BF 9343 (Cerdeno-Tarraga et al., 2005). Other plasmids frequently used in BF638R are also difficult or impossible to introduce into BF 9343 (data not shown). In general, more efficient transposon mutagenesis is achieved by prior modification of plasmid carrying the transposon by the host of interest.

DISCUSSION

We developed an improved system for transposon mutagenesis in BF using the EZ∷TN5 system. Previous attempts to mutagenize BF by transposons have been hindered by either vector integration and/or multiple insertions (Shoemaker et al., 1986, Chen et al., 2000a). Also, those methods often used labor-intensive filter mating techniques to introduce the DNA. The method described here has several advantages: 1) transposons can be introduced into BF by electroporation, 2) all insertion events are independent, 3) no vector delivery system is required and vector cointegration can be completely avoided, and 4) no suicide vector or native inducible promoters to drive transposase expression are needed. We found that the transposon inserts evenly across the chromosome. Also, analysis of the insertion points of the EZ∷TN5 transposon indicates that although there is some sequence context preferred of insertion by Tn5, the insertion is sufficiently random for its effective use in construction a library of transposon mutants (Shevchenko et al., 2002).

EZ∷TN5 transposon mutagenesis also provides flexibility for subsequent identification of the transposon-disrupted gene. For example, if the genome sequence is not available for the organism of interest, the genes adjacent to the mutated gene can be retrieved and identified by rescue cloning and sequencing. On the other hand, if the genome sequence is available, the mutated gene can be amplified by SRP-PCR, identified by genomic means and large numbers of mutants can be easily screened. Prior passage of the transposon vector in related strains increases downstream efficiency of transposon mutagenesis. This system provides a useful genetic tool which will facilitate deeper understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms of this important human commensal/pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research is based upon work supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development and in part by the NIAID (NIH) Grant Number 1R56AI083649-01A2. We would like to thank Drs. Elizabeth Tenorio and Yi Wen for their helpful comments and advice regarding mutant identification and Southern Blots, respectively.

Reference List

- Baughn AD, Malamy MH. A mitochondrial-like aconitase in the bacterium Bacteroides fragilis: implications for the evolution of the mitochondrial Krebs cycle. PG -. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99 doi: 10.1073/pnas.052710199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennion RS, Baron EJ, Thompson JE, Jr., Downes J, Summanen P, Talan DA, Finegold SM. The bacteriology of gangrenous and perforated appendicitis--revisited. Ann Surg. 1990;211:165–171. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199002000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg DE, Berg CM. The prokaryotic transposible element Tn5. Nature Biotechnology. 1983;1:417–435. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Patrick S, Crossman LC, et al. Extensive DNA inversions in the B. fragilis genome control variable gene expression. Science. 2005;307:1463–1465. doi: 10.1126/science.1107008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Dong H, Tang YP, Dallas MM, Malamy MH, Duncan MJ. Identification and cloning of genes from Porphyromonas gingivalis after mutagenesis with a modified Tn4400 transposon from Bacteroides fragilis. Infect Immun. 2000a;68:420–423. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.420-423.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Dong H, Yong R, Duncan MJ. Pleiotropic pigmentation mutants of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microb Pathog. 2000b;28:235–247. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1999.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua G, Taricani L, Stangle W, Young PG. Insertional mutagenesis based on illegitimate recombination in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E53. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.11.e53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desomer J, Crespi M, Van MM. Illegitimate integration of non-replicative vectors in the genome of Rhodococcus fascians upon electrotransformation as an insertional mutagenesis system. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2115–2124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher LA, Ramage E, Jacobs MA, Kaul R, Brittnacher M, Manoil C. A comprehensive transposon mutant library of Francisella novicida, a bioweapon surrogate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1009–1014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606713104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore MS, Ferretti JJ. Microbiology. The thin line between gut commensal and pathogen. Science. 2003;299:1999–2002. doi: 10.1126/science.1083534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggoud A, Trinh S, Moumni M, Reysset G. Genetic analysis of the minimal replicon of plasmid pIP417 and comparison with the other encoding 5-nitroimidazole resistance plasmids from Bacteroides spp. Plasmid. 1995;34:132–143. doi: 10.1006/plas.1995.9994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MA, Alwood A, Thaipisuttikul I, et al. Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14339–14344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036282100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalpana GV, Bloom BR, Jacobs WR., Jr Insertional mutagenesis and illegitimate recombination in mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5433–5437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurkiewicz P, Tang CM, Boone C, Holden DW. Signature-tagged mutagenesis: barcoding mutants for genome-wide screens. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:929–939. doi: 10.1038/nrg1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick S, Blakely GW, Houston S, et al. Twenty-eight divergent polysaccharide loci specifying within- and amongst-strain capsule diversity in three strains of Bacteroides fragilis. Microbiology. 2010;156:3255–3269. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.042978-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumbwe L, Chang A, Smith RL, Wexler HM. Clinical significance of overexpression of multiple RND-family efflux pumps in Bacteroides fragilis isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006a;58:543–548. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumbwe L, Ueda O, Chang A, Smith R, Wexler HM. Bacteroides fragilis BmeABC Efflux transporters are coordinately expressed and additively confer intrinsic multi-substrate resistance; Abstracts of the 2005 Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; Washington, D C. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pumbwe L, Ueda O, Yoshimura F, Chang A, Smith R, Wexler HM. Bacteroides fragilis BmeABC Efflux Systems Additively Confer Intrinsic Antimicrobial Resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006b;58:37–46. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyers AA, Bonheyo G, Shoemaker NB. Starting a new genetic system: lessons from Bacteroides. Methods. 2000;20:35–46. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko Y, Bouffard GG, Butterfield YS, Blakesley RW, Hartley JL, Young AC, Marra MA, Jones SJ, Touchman JW, Green ED. Systematic sequencing of cDNA clones using the transposon Tn5. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2469–2477. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.11.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker NB, Getty C, Gardner JF, Salyers AA. Tn4351 transposes in Bacteroides spp. and mediates the integration of plasmid R751 into the Bacteroides chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:929–936. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.929-936.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJ, Rollins LA, Parker AC. Nucleotide sequence determination and genetic analysis of the Bacteroides plasmid, pBI143. Plasmid. 1995;34:211–222. doi: 10.1006/plas.1995.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YP, Malamy MH. Isolation of Bacteroides fragilis mutants with in vivo growth defects by using Tn4400', a modified Tn4400 transposition system, and a new screening method. Infect Immun. 2000;68:415–419. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.415-419.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler HM. Bacteroides--The Good, the Bad, and the Nitty-Gritty. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:593–621. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler HM, Molitoris E, Molitoris D, Finegold SM. In vitro activity of levofloxacin against a selected group of anaerobic bacteria isolated from skin and soft tissue infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:984–986. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]