Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the technical success, clinical outcome and safety of percutaneously placed totally implantable venous power ports (TIVPPs) approved for high-pressure injections, and to analyse their value for arterial phase CT scans.

Methods

Retrospectively, we identified 204 patients who underwent TIVPP implantation in the forearm (n=152) or chest (n=52) between November 2009 and May 2011. Implantation via an upper arm (forearm port, FP) or subclavian vein (chest port, CP) was performed under sonographic and fluoroscopic guidance. Complications were evaluated following the standards of the Society of Interventional Radiology. Power injections via TIVPPs were analysed, focusing on adequate functioning and catheter's tip location after injection. Feasibility of automatic bolus triggering, peak injection pressure and arterial phase aortic enhancement were evaluated and compared with 50 patients who had had power injections via classic peripheral cannulas.

Results

Technical success was 100%. Procedure-related complications were not observed. Catheter-related thrombosis was diagnosed in 15 of 152 FPs (9.9%, 0.02/100 catheter days) and in 1 of 52 CPs (1.9%, 0.002/100 catheter days) (p<0.05). Infectious complications were diagnosed in 9 of 152 FPs (5.9%, 0.014/100 catheter days) and in 2 of 52 CPs (3.8%, 0.003/100 catheter days) (p>0.05). Arterial bolus triggering succeeded in all attempts; the mean injection pressure was 213.8 psi. Aortic enhancement did not significantly differ between injections via cannulas and TIVPPs (p>0.05).

Conclusions

TIVPPs can be implanted with high technical success rates, and are associated with low rates of complications if implanted with sonographic and fluoroscopic guidance. Power injections via TIVPPs are safe and result in satisfying arterial contrast. Conventional ports should be replaced by TIVPPs.

Totally implantable venous access ports (TIVAPs) are widely used and allow for administration of chemotherapy and artificial nutrition as well as blood sampling [1]. These devices have been evaluated extensively in various locations, e.g. the chest, upper arm and forearm, generally showing excellent results as to technical success and low rates of complications [1-3]. Two studies have compared results of port placement in the chest using a conventional non-image-guided surgical technique and in the arm using a percutaneous image-guided technique by interventional radiologists [4,5], but until now data comparing the outcome of percutaneous image-guided port implantation in the chest and forearm seem to be limited.

Traditionally, TIVAPs were not approved for power contrast injections, e.g. during contrast-enhanced CT (ceCT), or were limited regarding injection pressure and flow [6]. Power contrast injections via TIVAPs have been evaluated in vitro, but only a few data on in vivo use of power injections via TIVAPs exist [6-8]. Recently, devices approved for power contrast injections (totally implantable venous power ports, TIVPPs) have been developed, but until today literature regarding the safety and use of power injections via these devices is limited to only one study on chest ports [9]. To satisfy the need for more data, we conducted a study to compare the technical success and safety of TIVPPs implanted in the forearm and the chest by interventional radiologists using image guidance and to analyse the safety of power contrast injections via TIVPPs as well as the feasibility of bolus triggering during arterial phase scans for ceCT.

Methods and materials

In this retrospective study, we identified 204 oncological patients (98 men, 106 women; mean age, 58.8±13.6 years; range, 18–88 years) who underwent percutaneous TIVPP implantation between November 2009 and May 2011. Patients' demographic and baseline characteristics are highlighted in Table 1. Indications for TIVPP insertion included chemotherapy and frequent blood sampling. All patients were examined and treated as part of routine care, and provided informed consent. Institutional review board approval was not required.

Table 1. Patients' demographic and baseline characteristics (n=204).

| Characteristic | Result | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 98 | |

| Female | 106 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 58.8 (13.6) | |

| Range | 18–88 | |

| Underlying malignancy | Chest port (n=52) | Forearm port (n=152) |

| Lymphoma | 13 (6.4) | 43 (21.1) |

| Breast cancer | 14 (6.9) | 20 (9.8) |

| Ovarian cancer | 2 (1.0) | 24 (11.8) |

| Uterine cancer | 1 (0.5) | 17 (8.3) |

| Leukaemia | 2 (1.0) | 11 (5.4) |

| Airway cancer | 3 (1.5) | 7 (3.4) |

| Gastric cancer | 0 (0.0) | 10 (4.9) |

| Colorectal cancer | 10 (4.9) | 5 (2.5) |

| Osteosarcoma | 2 (1.0) | 4 (2.0) |

| Oesophagus cancer | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.5) |

| Melanoma | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| Sarcoma | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other malignancies | 3 (1.5) | 6 (2.9) |

SD, standard deviation.

Data are given as number or number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

Inclusion criteria were age >18 years, port placement in our department as described below, and follow-up >30 days from the last power injection. The exclusion criterion was use of the TIVPP for chemotherapy outside our clinic.

Devices and technique of implantation

Implantation was performed by four interventional radiologists with several years of experience (2, 4 and 12 years) as well as by an interventional radiologist in training under supervision (with 6 months' experience). All procedures were carried out in our angiography suite under local anaesthesia and sterile conditions. No patient received sedation.

Whenever possible, the device was placed on the non-dominant side or hand. In patients who had undergone lymphadenectomy for breast cancer, the device was placed on the contralateral side, regardless of whether or not it was the dominant hand. The type and location of port implantation was subject to patients' decisions following informed consent. All patients received 2 g of ceftriaxone-dinatrium (broad-spectrum cephalosporin) intravenously for infection prophylaxis. In cases of a known allergy to penicillin (n=4), the patient received an alternative antibiotic [100 mg of ciprofloxacin (third-generation fluoroquinolone)] from the referring physician on the ward.

At the end of the procedure, all TIVPPs were accessed with a non-coring puncture needle, and after aspiration of blood, a contrast agent (Imeron 300; Bracco Imaging, Milan, Italy) was injected under fluoroscopy to verify a tight connection of the port stem and the catheter as well as adequate contrast agent distribution centrally. Before needle removal, the catheter was flushed with 3–4 ml of heparinised sodium chloride (100 U ml−1). Following pectoral implantation, pneumothorax was ruled out by chest X-ray after expiration.

Two different devices were used. For pectoral placement (n=52), the PowerPort® (Bard Access Systems, Salt Lake City, UT) was used. Following local anaesthesia (mepivacaine 1%) and under sonographic guidance, the subclavian vein was accessed using the Micropuncture® Introducer Set (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN). Subsequently, an 8-F peel-away sheath was placed in the subclavian vein. Following preparation of the port pocket in the chest, a tunnelling device was used to cross the distance between the pocket and the initial puncture site subcutaneously. The catheter tip was inserted via the peel-away sheath under fluoroscopic guidance and placed centrally with the tip aiming at the vertebral body below the carina. After tunnelling the distance between the initial vascular access site and the pocket, the catheter was cut to adequate length and connected to the port chamber. Correct and central placement of the catheter tip as well as the loop-free run of the catheter in the tunnelled area was documented by fluoroscopy (Figure 1). The port was not fixed to the pectoral muscle fascia. The pocket was closed with two layers of suture, while the vascular access site was closed with one cutaneous stitch only.

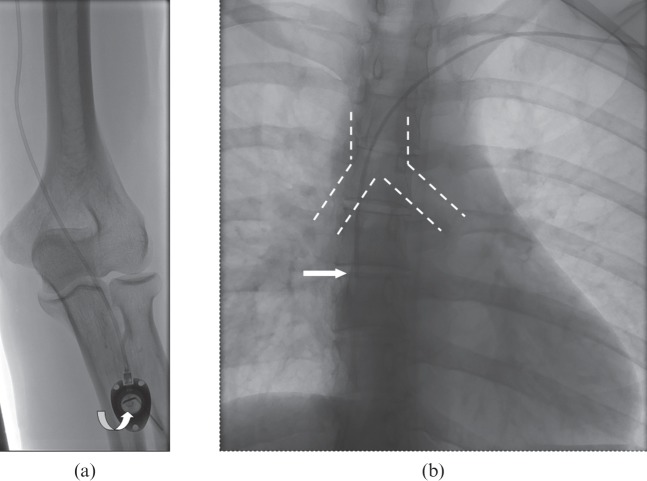

Figure 1.

Totally implantable venous power port of the chest. The image was taken following implantation of the device via the left subclavian vein. The smooth curve of the port catheter and catheter tip (arrow) can be seen in the cavo-atrial junction. The curved arrow marks the letters “CT”, which are imprinted on the port chamber to clearly identify the port as a high-pressure tolerating device.

For TIVPP placement in the forearm (n=152), the P.A.S. PORT® T2 POWER P.A.C. (Smiths Medical, St Paul, MN) was used (Figure 2). Deep vein thrombosis of the upper arm was excluded by colour duplex and compression sonography. A blood pressure cuff was placed on the upper arm and inflated just below systolic pressure using colour duplex sonography. Using sonographic guidance, the largest vein of the upper arm was punctured with an 18-G (gauge) introducer needle at the midpoint of the medial upper arm. Following local anaesthesia (mepivacaine 1%), a 0.035-inch guidewire was inserted under fluoroscopic control and a peel-away sheath was established. Subsequently, an incision was made at the previously anaesthetised area on the forearm and a subcutaneous pocket was prepared distal to the incision site. Then the tunnelling device (“tunneller”) was inserted subcutaneously between the prepared pocket and the initial puncture site on the upper arm. The catheter tip was inserted and placed centrally via the peel-away sheath, with the tip aiming at the vertebral body below the carina. The tunneller with the catheter was then pulled distally, tunnelling subcutaneously the distance between initial vascular access on the upper arm and the prepared pocket on the forearm. After this, the catheter end was connected to the port, which was then implanted in the subcutaneous pocket. Correct and central placement of the catheter tip as well as the loop-free run in the tunnelled elbow area was documented by fluoroscopy. The port was not fixed with suture material in the subcutaneous pocket.

Figure 2.

Totally implantable venous power port of the forearm. (a) Image after implantation of the device distal to the cubital fossa with a smooth curve of the catheter crossing the elbow. As with the pectoral device, the letters “CT” (curved arrow) are imprinted on the port chamber to identify the port as a high-pressure tolerating device. The port needle is still in place. (b) The catheter tip is located at the height of the vertebral body below the carina (broken lines).

Evaluation of power contrast injections via power ports

Examinations were carried out using a 64-row CT scanner (SOMATOM Sensation64w; Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) and a contrast agent containing 300 mg ml−1 of iodine (Imeron 300; Bracco Imaging SpA, Milan, Italy). The high-pressure injector was connected to the port needle using a Luer locking device (Original-Perfusor® tubing; B Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany). We fixed the port needle with an adhesive tape (as we do regularly), although the manufacturers do not specifically instruct this. In all cases, a saline chase of 40 ml was used and the arterial phase was part of a multiphase scan. Bolus triggering was carried out with the region of interest localised in the proximal abdominal aorta. The trigger threshold was set at 120 HU. Our protocol for arterial scans includes a 5 s delay after the threshold level has been reached and before the scan is initiated. The protocol for contrast injection via a TIVPP in our radiology department includes aspiration of blood after the TIVPP has been accessed with our standard non-coring 20 G needle (EZ HUBER®; Pfm Medical, Inc, Oceanside, CA), and evaluation of the initial anteroposterior scout view to confirm correct localisation of the catheter tip. Injections were performed at 3 ml s−1 and the injection pressure limit was set at 300 psi. The non-coring needle was fixed with adhesive tape to the top of the needle. Peak injection pressures were given by our standard power injector (Stellant®; MedRad, Warrendale, PA) at the end of the injection. Catheter tip location before and after the power injection was analysed by reviewing either the CT scan of the chest or, if this was not available (e.g. after a CT scan of the abdomen only), any chest X-ray performed after the injection. Catheter dislocation was defined as tip location cranial to the carina in a previously correctly (infracarinally) placed TIVPP or a reverse movement of >2 cm in any catheter located cranial to the carinal level. Special attention was given as to whether or why a TIVPP needed explantation following power injections. If bolus triggering for arterial scans was carried out, attenuation levels of the abdominal aorta at the origin of the coeliac trunk were measured in the arterial phase. Further attention was given as to whether the threshold in the region of interest was reached and the scan was triggered automatically, or whether manual scan initiation had become necessary.

Evaluation of power contrast injections via standard peripheral venous access

CT scans of 50 consecutive cancer patients (19 women, 31 men; mean age, 64±13 years) who underwent power injections with bolus triggering via classic peripheral 18-G (n=25) or 20-G (n=25) catheters (Braunüle®; Braun, Melsungen, Germany) for arterial phase scans were evaluated. These examinations were carried out on the scanner mentioned above using the same contrast agent and injector, also with a flow rate of 3 ml s−1, an injection pressure limit of 300 psi and a saline flush of 40 ml. Attenuation levels of the aorta were measured at the same level as described earlier.

Data evaluation and endpoint definition

Angiograms and angiographic and medical records after percutaneous port implantation were reviewed to gather information on technical success, clinical outcome and complication rates. The primary endpoints of our study were technical success, clinical outcome, procedure-related complications and rates of minor and major complications. The secondary endpoints included the performance of power contrast injections and aortic contrast enhancement during arterial phase scans.

Technical success was defined as catheter introduction into the venous system with the tip position 1–2 cm below the carina, and adequate catheter function indicated by aspiration of blood, infusion of saline into the device without significant resistance and angiographic documentation of a correct position. Clinical outcome was reflected by device failure that was determined by any limitation in catheter function despite technically successful catheter placement. The initial device service interval was defined as the number of catheter-days from the implantation procedure until removal at completion of therapy, patient death, end of study with the catheter still functioning or device failure. Minor and major complications were categorised on the basis of outcome according to the reporting standards of the Society of Interventional Radiology [10]. Complications were classified as early (<30 days from implantation) or late (>30 days from the procedure).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were presented as mean ± standard deviation and range, if appropriate; categorical data were provided as counts and percentages. For comparison of complication rates between the chest and forearm groups within this study sample, the non-parametric two-sample Mann–Whitney test was used. For calculation of complication-free survival, the Kaplan–Meier method was used. The relationship between power injections via a classic peripheral cannula and TIVPP regarding the aortic enhancement was tested using the independent samples t-test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Statistical analysis was performed by a specialised computer algorithm (SPSS v. 11.5; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

In total, 63 588 (FP: 50 834; CP: 12 754) catheter-days were observed. 156 of 204 (76.5%) ports were implanted on the left side and 48 of 204 (23.5%) ports were implanted on the right side. Device placement was successful in all patients, resulting in a technical success of 100%. Procedure-related complications such as pneumothorax or accidental arterial puncture were not observed. We observed no malrotation of the port in the subcutaneous pocket. In total, 36 of 204 (17.6%) TIVPPs showed a complication; 11 (5.4%) were classified as having an early complication and 25 (12.3%) were classified as having a late complication. Table 2 summarises the type and number of complications observed during device service intervals. In total, 19 of 204 TIVPPs (9.3%) were removed. Table 3 highlights the indications for explantation (n=21) of those devices. Complication-free survival of patients with FPs and CPs is highlighted in a Kaplan–Meier graph (Figure 3).

Table 2. Type and number of complications in patients with chest and forearm ports.

| Patients with chest ports (n=52) |

Patients with forearm ports (n=152) |

||||||

| Complication | Number | Percentage | Per 100 catheter-days | Number | Percentage | Per 100 catheter-days | p-value |

| CRT | 1 | 1.9 | 0.002 | 15 | 9.9 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Infection | 3 | 5.8 | 0.005 | 9 | 5.9 | 0.014 | 0.46 |

| Thrombus at catheter tip | 1 | 1.9 | 0.002 | 6 | 4.0 | 0.009 | 0.16 |

| Dislocation of catheter tip | 1 | 1.9 | 0.002 | 0 | 0.0 | N/A | N/A |

CRT, catheter-related thrombosis; N/A, not applicable.

Table 3. Reasons for removal of totally implantable venous power ports (n=204).

| Reason for removal | Chest port (n=52) | Forearm port (n=152) |

| Infection | 3 (5.8) | 9 (5.9) |

| End of therapy | 3 (5.8) | 3 (2.0) |

Data are given as number (percentage).

Figure 3.

Freedom from complication after totally implantable venous power port (TIVPP) implantation in the forearm (FP) and the chest (CP) displayed as a Kaplan–Meier graph.

Evaluation of power contrast injections

In 203 of 204 (99.5%) patients, the catheter tip was located caudal to the carina. 1 (2.1%) catheter tip was located in the contralateral brachiocephalic vein, although the device had not been used for high-pressure injections.

Altogether, 90 of 204 (44.1%) port devices were used for 117 high-pressure injections. Of 90 patients, 73 (81.1%) had 1, 10 (11.1%) had 2, 5 (5.6%) had 3, 1 (1.1%) had 4 and 1 (1.1%) had 5 power injections via the TIVPP during repetitive ceCT scans. In 36 of 117 (30.8%) power injections, arterial bolus triggering was attempted and succeeded in all (100%) attempts. In 3 of 204 (1.5%) patients, a high-pressure injection was used to exclude pulmonary embolism; image quality was found to be satisfying regarding pulmonary artery contrast. Neither detachment of port catheter from port stem nor from the needle and the port was observed. Extravasation following high-pressure injections was not observed. The mean injection pressure of all injections via TIVPPs was 213.8 psi. The aortic enhancement during the arterial phase scans did not significantly differ between injections via cannulas (214.7±33.8 HU) or TIVPPs (223.7±38.8 HU) (p=0.27).

Discussion

TIVAPs represent an integral part of therapy for oncological patients and offer several advantages over externalised catheter systems [11]. In numerous studies, these devices were evaluated at various implantation sites such as the chest, upper arm and forearm [1,2,12]. Literature comparing the outcome after arm and chest port placement is rare, and in present studies chest ports were mostly implanted using conventional non-image-guided surgical techniques (internal jugular or cephalic vein access), while a percutaneous image-guided technique was used for implantation in the upper arm [4,5]. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to compare technical and clinical data of TIVPP implantation in the chest and the forearm by interventionists using sonographic and fluoroscopic guidance.

Regarding implantation in the chest, the high rate of technical success in our study concurs with results from other trials reporting technical success rates between 71% and 100% [13,14]. Although it has been hypothesised that implantation via the subclavian vein results in a higher rate of pneumothorax than access via the internal jugular vein [1,15], we observed no cases of pneumothorax in our series. In this context, two technical factors appear to be crucial. Firstly, the needle for vessel puncture should be as small as possible, e.g. as included in the micropuncture set used in our study, to minimise the risk of pneumothorax. Secondly, image guidance should be used for target vessel puncture as well as for catheter insertion and tip placement [16]. As demonstrated in our series, a combination of both not only helps to avoid the risk of pneumothorax but also averts accidental arterial puncture. Therefore, chest port placement using a percutaneous image-guided technique (e.g. as used by many interventionists) may result in higher rates of technical success and lower rates of complications than the conventional non-image-guided surgical technique, as hypothesised by others before [17,18]. Another advantage of radiological placement could be the fact that no operating theatre time is necessary and implantation can be performed in an outpatient setting [11]. Both facts may reduce overall procedure-related costs.

In our study, infectious complications did not differ significantly between TIVPPs implanted in the chest and those implanted in the forearm. Catheter-related thrombosis was found significantly more frequently in patients with forearm ports, a fact that has been described in previous studies and which represents a disadvantage of (fore)arm port placement [3,5]. On the other hand, compared with implantation in the chest, the forearm position may offer advantages, e.g. more desirable cosmetic results, absence of interference during mammographic or chest imaging, less perceived pain during implantation and reduced foreign body perception [19,20]. In addition, for patients with head and neck cancer, the arm has been described as the preferable implantation site [21].

Recently, TIVPPs, which are approved for power contrast injections, have been introduced. This additional feature of a port device may increase patient comfort, given that oncological patients undergo repetitive ceCT examinations for staging, restaging and evaluation of complications during the course of chemotherapy. Our data show that nearly half of the devices are used for contrast application for diagnostic imaging.

So far, data on high-pressure tolerating ports are limited, with only one study having evaluated the outcome of chest ports implanted via the internal jugular vein [9]; like these authors, we also observed the same high technical success rate as with conventional TIVAPs. In addition, we also observed no adverse effects during or following power injections via TIVPPs. Similar to Wieners et al [9], we found more satisfying aortic contrast enhancement after injections via TIVPPs than via classic peripheral cannulas. Furthermore, our data show that bolus triggering during power injections in TIVPPs is feasible: a clear advantage over conventional TIVAPs, in which bolus triggering is an off-label use and has been shown to succeed in only one-third of attempts [8]. An adequate aortic contrast enhancement, which relies on sufficient flow rates and injection pressure during contrast administration, is important because it correlates with detection rates of liver lesions with hypervascularisation, e.g. metastasis [22]. Because oncological patients are prone to thrombo-embolic incidents, pulmonary embolism frequently needs to be excluded. To attain this, adequate contrast of the pulmonary arteries is mandatory during CT scans and can be achieved only by following a high-pressure injection with a flow rate of 3–4 ml s−1 or more, which is now possible with these devices.

Surprisingly, we did not observe an increased rate of catheter tip dislocation in TIVPPs, although one may expect that with increasing injection pressures and flow rates, catheter tips may be pushed backwards more easily than with lower injection pressures and flow rates. Furthermore, we did not observe disconnection of the port catheter from the port stem, although some patients underwent repeated high-pressure injections. In concordance with others, we observed no malrotation of the port chamber, so fixation to the fascia seems unnecessary for both locations used in this study [3,23].

If ports are to be used for high-pressure injections, qualified personnel are required to access the device, locate the catheter tip on the anterior–posterior scout and flush the device after injection followed by needle removal. Comparing the costs of both TIVPPs, the forearm port (€79) is less expensive than the pectoral device (€185 plus the micropuncture set at €39); as a result, the peripheral approach is more cost-effective.

There are significant limitations to this study. Firstly, this series is retrospective and lacks randomisation. Therefore, patient selection bias may be present in our findings. A prospective randomised trial would be beneficial to define the exact value, clinical outcome and complication rates of TIVPP implantation in the forearm and chest. Furthermore, only clinically relevant complications could be analysed, owing to the retrospective character of this study; silent thrombosis or intravascular port catheter rupture might have occurred without being detected in our study sample. The fact that most of our patients were categorised as having been pre-treated with chemotherapeutic agents may have influenced our overall results. Therefore, heterogeneous study samples would be advantageous to make a clear segregation between non-treated and pre-treated patients.

We conclude that implantation of TIVPPs in the chest or forearm is a safe and feasible procedure with a high technical success rate when using a percutaneous image-guided approach. Bolus triggering during power injections via high-pressure tolerating devices is feasible and safe, and results in adequate aortic enhancement. Given the choice, TIVPPs should be preferred and should replace conventional devices. If a TIVPP has been implanted, it can be used for power injections without increased risks instead of establishing an additional peripheral venous access. This may increase patient comfort during diagnostic imaging.

References

- 1.Kock HJ, Pietsch M, Krause U, Wilke H, Eigler FW. Implantable vascular access systems: experience in 1500 patients with totally implanted central venous port systems. World J Surg 1998;22:12–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawamura J, Nagayama S, Nomura A, Itami A, Okabe H, Sato S, et al. Long-term outcomes of peripheral arm ports implanted in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2008;13:349–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goltz JP, Scholl A, Ritter CO, Wittenberg G, Hahn D, Kickuth R. Peripherally placed totally implantable venous-access port systems of the forearm: clinical experience in 763 consecutive patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010;33:1159–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcy PY, Magne N, Castadot P, Bailet C, Macchiavello JC, Namer M, et al. Radiological and surgical placement of port devices: a 4-year institutional analysis of procedure performance, quality of life and cost in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2005;92:61–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuriakose P, Colon-Otero G, Paz-Fumagalli R. Risk of deep venous thrombosis associated with chest versus arm central venous subcutaneous port catheters: a 5-year single-institution retrospective study. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2002;13:179–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herts BR, O'Malley CM, Wirth SL, Lieber ML, Pohlman B. Power injection of contrast media using central venous catheters: feasibility, safety, and efficacy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;176:447–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gebauer B, Teichgräber UK, Hothan T, Felix R, Wagner HJ. Contrast media pressure injection using a portal catheter system—results of an in vitro study. Rofo 2005;177:1417–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goltz JP, Machann W, Noack C, Hahn D, Kickuth R. Feasibility of power contrast injections and bolus triggering during CT scans in oncologic patients with totally implantable venous access ports of the forearm. Acta Radiol 2011;52:41–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wieners G, Redlich U, Dudeck O, Schütte K, Ricke J, Pech M. First experiences with intravenous port systems authorized for high pressure injection of contrast agent in multiphasic computed tomography. Rofo 2009;181:664–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sacks D, McClenny TE, Cardella JF, Lewis CA. Society of Interventional Radiology clinical practice guidelines. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2003;14:S199–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vardy J, Engelhardt K, Cox K, Jacquet J, McDade A, Boyer M, et al. Long-term outcome of radiological-guided insertion of implanted central venous access port devices (CVAPD) for the delivery of chemotherapy in cancer patients: institutional experience and review of the literature. Br J Cancer 2004;91:1045–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenhart M, Schätzler S, Manke C, Strotzer M, Seitz J, Gmeinwieser J, et al. Radiological placement of peripheral central venous access ports at the forearm. Technical results and long term outcome in 391 patients. Rofo 2010;182:20–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nocito A, Wildi S, Rufibach K, Clavien PA, Weber M. Randomized clinical trial comparing venous cutdown with the Seldinger technique for placement of implantable venous access ports. Br J Surg 2009;96:1129–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teichgraber UK, Streitparth F, Cho CH, Benter T, Gebauer B. A comparison of clinical outcomes with regular- and low-profile totally implanted central venous port systems. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2009;32:975–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakamoto N, Arai Y, Takeuchi Y, Takahashi M, Tsurusaki M, Sugimura K. Ultrasound-guided radiological placement of central venous port via the subclavian vein: a retrospective analysis of 500 cases at a single institute. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2012; in press. E-pub ahead of print April 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plumhans C, Mahnken AH, Ocklenburg C, Keil S, Behrendt FF, Gunther RW, et al. Jugular versus subclavian totally implantable access ports: catheter position, complications and intrainterventional pain perception. Eur J Radiol 2011;79:338–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gebauer B, El-Sheik M, Vogt M, Wagner HJ. Combined ultrasound and fluoroscopy guided port catheter implantation—high success and low complication rate. Eur J Radiol 2009;69:517–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cil BE, Canyigit M, Peynircioglu B, Hazirolan T, Carkaci S, Cekirge S, et al. Subcutaneous venous port implantation in adult patients: a single center experience. Diagn Interv Radiol 2006;12:93–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goltz JP, Kickuth R. Reply to letter: further data about upper extremity ports. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2011;34:659–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcy PY, Figl A, Ianessi A, Chamorey E. Central and peripheral venous port catheters: evaluation of patients' satisfaction under local anesthesia. J Vasc Access 2010;11:177–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcy PY, Chamorey E, Amoretti N, Benezery K, Bensadoun RJ, Bozec A, et al. A comparison between distal and proximal port device insertion in head and neck cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2008;34:1262–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanaga Y, Awai K, Nakayama Y, Nakaura T, Tamura Y, Funama Y, et al. Optimal dose and injection duration (injection rate) of contrast material for depiction of hypervascular hepatocellular carcinomas by multidetector CT. Radiat Med 2007;25:278–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNulty NJ, Perrich KD, Silas AM, Linville RM, Forauer AR. Implantable subcutaneous venous access devices: is port fixation necessary? A review of 534 cases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010;33:751–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]