Abstract

BACKGROUND

Preeclampsia is considered a disease of immunological origin associated with abnormalities in inflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and activated lymphocytes secreting AT1-AA. Recent studies have also demonstrated that an imbalance of angiogenic factors, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFlt-1), and sEndoglin, exists in preeclampsia; however, the mechanisms that initiate their overproduction are unclear.

METHODS

To determine the role of immune regulation of these factors, circulating and placental sFlt-1 and/or sEndoglin was examined from pregnant rats chronically treated with TNF-α or AT1-AA. On day 19 of gestation blood pressure was analyzed and serum and tissues were collected. Placental villous explants were excised and cultured on matrigel coated inserts for 24 h and sFlt-1 and sEndoglin was measured from media.

RESULTS

In response to TNF-α-induced hypertension, sFlt-1 increased from 180 ± 5 to 2,907 ± 412 pg/ml. sFlt-1 was also increased from cultured placental explants of TNF-α induced hypertensive pregnant rats (n = 12) (2,544 ± 1,132 pg/ml) vs. explants from normal pregnant (NP) rats (n = 12) (2,189 ± 586 pg/ml) where as sEng was undetectable. Circulating sFlt-1 increased from 245 ± 38 to 3,920 ± 798 pg/ml in response to AT1-AA induced hypertension. sFlt-1 levels were higher (3,400 ± 350 vs. 2,480 ± 900 pg/ml) in placental explants from AT1-AA infused rats (n = 12) than NP rats (n = 7). In addition, sEndoglin increased from 30 ± 2.7 to 44 ± 3.3 pg/ml (P < 0.047) in AT1-AA infused rats but was undetectable in the media of the placental explants.

CONCLUSIONS

These data suggest that immune factors may serve as an important stimulus for both sFlt-1 and sEndoglin production in response to placental ischemia.

Keywords: antiangiogenic factors, blood pressure, hypertension, immune activation, pregnancy

Preeclampsia is a complex disease that affects 5–7% of pregnancies in the United States. Although preeclampsia is one of the leading causes of maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity, the pathophysiologic mechanism(s) underlying this disease has yet to be fully elucidated. However, reductions in blood flow to the uteroplacental unit are thought to be an important initiating factor in the etiology of preeclampsia. Thus, the physiologic mechanisms linking placental ischemia with abnormalities in the maternal circulation remain to be an important area of investigation.1,2 Recent clinical evidence has demonstrated an imbalance between proangiogenic (e.g., vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor) and antiangiogenic factors (e.g., soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFlt-1) and sEndoglin (sEng)) in the maternal circulation.3–9 Subsequent research indicates that plasma, placental mRNA and amniotic fluid concentrations of sFlt-1 are increased in preeclamptic patients.3–9 Elevated sFlt-1 and sEng levels in preeclamptic women are associated with increased levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and autoantibodies to the angiotensin II receptor (AT1-AA).10–16 Whereas an abnormality in sFlt-1 and sEng production is thought to be a trigger in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia, the mechanisms that regulate sFlt-1 and sEng production remain unclear.

We have recently reported that the hypertension in response to placental ischemia is associated with increases in plasma levels of sFlt-1, sEng, TNF-α, and AT1-AA.17,18 We also demonstrated that chronic infusion of TNF-α or AT1-AA, at rates to mimic the increase of these factors observed in placental ischemic pregnant rats, significantly contributes to elevated blood pressures.17–21 Moreover, we found that chronic infusion of TNF-α in pregnant rats stimulated the production of AT1-AA and the blood pressure response to TNF-α or AT1-AA were attenuated by treatment with an angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonist.18,21 Although these findings suggest an important interaction between TNF-α and AT1-AA in the blood pressure response to placental ischemia, it is unknown whether these factors interact in regulating sFlt-1 and sEng production. Therefore, we repeated previous studies in order to determine whether chronic infusion of TNF-α or AT1-AA, at a rate to mimic levels previously observed in placental ischemic pregnant rats,18,19 effects placental and plasma levels of sFlt-1 and sEng.

METHODS

All studies were performed in 250 g first timed pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). Animals were housed in a temperature controlled room (23 °C) with a 12:12 light:dark cycle. All experimental procedures executed in this study were in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for use and care of animals. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Protocol 1a: Effect of chronic TNF on sFlt-1 in pregnant rats

This portion of the experiment was performed to determine the role of TNF-α induced hypertension in stimulating sFlt-1 production. Previous experiments show significant increases in mean arterial pressure (MAP) with TNF-α infusion from day 14 to 19 of gestation.18–20 These experiments were performed in normal pregnant (NP) rats divided into two groups: NP, n = 12, and chronic TNF-α infused rats, n = 12. TNF-α (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA) was infused at a rate of 50 ng/day for 5 days (day 14–19 gestation) via mini-osmotic pumps (model 2002; Alzet Scientific, Palto Alto, CA) inserted into the intraperitoneal cavity of NP rats. On day 18 of gestation, these rats were surgically instrumented with a carotid catheter for subsequent arterial pressure measurement. At day 19 of gestation, the arterial pressure was measured and blood samples and placentas were collected for cultivation and sFlt-1 measurements.

Protocol 1b: Effect of chronic AT1-receptor antagonism on TNF-α induced sFlt-1 in pregnant rats

Previous experiments show that AT1-receptor blockade blunts hypertension in response to chronic TNF-α. This portion of the study was performed in order to determine the role of the AT1-receptor activation in mediating TNF-α induced sFlt-1. TNF-α was infused into NP rats treated with the AT1-receptor antagonist, losartan (Merck & Co., Whitehouse Station, NJ), in the drinking water. Experiments were performed in two groups of rats: NP rats treated orally with losartan (10 mg/day) (n = 8), and chronic TNF-α infused rats treated orally with losartan (10 mg/day) (n = 8).

Isolation and purification of rat AT1-AA

The female hAogen × male hRen (MDC, Berlin) pregnant transgenic rats (MDC, Berlin) were used as the source of rat AT1-AA.19,21,22 This model develops hypertension associated with the AT1-AA. On day 18 of gestation, blood was collected and immunoglobulin was isolated from 1 ml of serum by specific anti-rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) column purification. AT1-AA was purified from rat IgG by epitope binding to the amino acid sequence corresponding to the second extracellular loop of the AT1 receptor covalently linked to Sepharose 4B CNBr-activated gel. Unbound IgG was washed away and bound IgG was eluted with 3 M potassium thiocyanate. AT1-AA activity was measured utilizing a bioassay that evaluates the beats per minute (bpm) of neonatal cardiomyocytes in culture.14–16,21,22

Protocol 2: Effect of chronic rat AT1-AA on sFlt-1 in pregnant rats

Previously published experiments demonstrate significant increases in MAP with in this fusion of AT1-AA from day 12 to day 19 of gestation. Twelve microliters/day of (1:50) purified rat AT1-AA fraction (collected as described above) diluted in saline was infused into pregnant rats for 7 days.19,21–23 We have shown this procedure to produce hypertension during pregnancy. Purified rat AT1-AA was infused intraperitoneally from day 12 to 19 of gestation via miniosmotic pumps (model 2002, Alzet Scientific Corporation) into NP rats.21 Serum AT1-AA concentrations and activity was determined utilizing the procedure outlined above from 1 ml of serum collected on day 19 of gestation from NP control rats (n = 15) and pregnant rats treated chronically with AT1-AA (n = 17). On day 18 of gestation, all rats were surgically instrumented with a carotid catheter for subsequent arterial pressure measurement. At day 19 of gestation, arterial pressure was measured, a blood sample was collected, kidneys and placentas were harvested and litter size and pup weights were recorded.

Measurement of MAP in chronically instrumented conscious rats

Arterial pressure was determined in all groups of rats at day 19 of gestation.18–21 Pregnant rats were catheterized on day 18 of gestation under anesthesia using isoflurane (Webster, Sterling, MA) delivered by an anesthesia apparatus (Vaporizer for Forane Anesthetic, Ohio Medical Products, Madison, WI). A catheter of V-3 tubing (SCI, Lake Havasu City, AZ) was inserted into the carotid artery for blood pressure monitoring. The catheter was tunneled to the back of the neck and exteriorized after implantation. On day 19 of gestation, pregnant rats were placed in individual restraining cages for arterial pressure measurements. Arterial pressure was monitored with a pressure transducer (Cobe III Transducer CDX Sema, Birmingham, AL) and was recorded continuously for a 2 h period following 1 h stabilization.18–21

Placental explant model

Freshly harvested placentas were rinsed in cold phosphate buffered saline and the myometrium layer was isolated from the decidua and the vascular bundle was excised. Villous explants were plated on matrigel 6-well cell culture filter inserts, and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F12 supplemented with 0.25 µg/ml ascorbate and 10U Pen/Strep at 37 °C, 6% O2, 89% N2, 5% CO2 conditions. Culture media was removed, stored at −80 °C, and later used to determine sFlt-1 and sEng concentrations.

Determination of serum TNF-α levels

A rat tumor necrosis factor-α colorimetric sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was used for quantification of serum TNF-α levels between 12.5 and 800 pg/ml. This assay displayed a sensitivity level of 5 pg/ml with an interassay variability of 10% and intra-assay of 5.1%, as defined by the manufacturer.

Determination of AT1-AA levels

Antibodies were detected by the chronotropic responses to AT1 receptor–mediated stimulation of cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes coupled with receptor-specific antagonists as previously described above. Chronotropic responses were measured and expressed in beats per minute (bpm).14–16,19–21

Determination of sFlt-1 and sEng levels

Circulating sFlt-1 was determined from plasma isolated on ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Placental sFlt-1 was determined from cell culture supernatant collected following 24 h of cultivation. sFlt-1 levels were determined using the murine vascular endothelial growth factor R1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay from R&D Systems. The variability for intra-assay was 7.2% and interassay was 8.4%. Circulation sEndoglin was determined from plasma isolated on ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid using the human sEndoglin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay purchased from R&D Systems. Rat endoglin shares 71% identity with human endoglin and is appropriately detectable by the RnD kit human endoglin. The lower detection limit is 156 pg/ml and the variability for intra-assay was 3.0% and interassay was 6.7%.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± s.e. Differences between control and experimental groups were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. Differences between multiple groups were analyzed via one-way analysis of variance and post hoc analyses were obtained through the utilization of the Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test. Associations were considered significant if the P value was <0.05.

RESULTS

Protocol 1a: Effect of Chronic TNF-α on sFlt-1 and sEng production

Serum sFlt-1 increased significantly from 180 ± 5 pg/ml in NP rats to 2,907 ± 412 pg/ml in response to TNF-α induced hypertension (Figure 1). Chronic infusion of TNF-α into pregnant rats resulted in significant increases in MAP relative to NP control rats18–20 when circulating TNF-α levels were elevated two- to threefold at day 19 of pregnancy.18–20 Pregnant control rats had a MAP of 101 ± 2 mm Hg and circulating TNF-α levels at 55.6 pg/ml. MAP increased with TNF-α administration to 115 ± 3 mm Hg (P ≤ 0.01 vs. NP), while circulating TNF-α increased to 106 ± 34 pg/ml. sEng was undetectable, below the detection limits of the assay, in response to chronic TNF-α.

Figure 1.

Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. (a) Plasma sFlt-1 levels in response to TNF-α infusion. (b) Treatment with an angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonist compared to controls (*P < 0.05).

Protocol 1b: sFlt-1 in response to AT 1-receptor blockade of TNF-α induced hypertension

As we have shown previously, treatment with an AT1-receptor antagonist blunted the increase in blood pressure in response to the twofold increase in circulating TNF-α.18 MAP of losartan treated control rats was 99 ± 3 mm Hg with circulating TNF-α levels of 62 ± 21 pg/ml. MAP in response to TNF-α in losartan treated rats was 107 ± 3 mm Hg even though circulating TNF-α was increased to 112 ± 30 pg/ml. In addition, circulating sFlt-1 stimulated in response to TNF-α induced hypertension was completely abolished with an AT1-receptor antagonist. sFlt-1 was 388 ± 266 pg/ml in NP + AT1-receptor antagonist and levels in the TNF-α infused pregnant rats were 491 ± 212 pg/ml with AT1-receptor antagonism (Figure 1).

Placental sFlt-1 in response to chronic TNF-α

Placental explants from NP and TNF-α infused pregnant rats were cultured overnight and sFlt-1 concentrations were determined from cell culture media. sFlt-1 production was elevated in cultured placental explants of TNF-α induced hypertensive pregnant rats (3,090 ± 932 pg/ml) (n = 9) compared to NP rats (2,189 ± 586 pg/ml) (n = 7) (Figure 2). In addition, AT1-receptor blockade blunted placental sFlt-1 secretion in the response to TNF-α induced hypertension.

Figure 2.

Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Placental sFlt-1 levels in response to TNF-α infusion compared to the normal pregnant (NP) control group (*P < 0.05).

Protocol 2: Effect of chronic AT 1-AA on sFlt-1 and sEng production

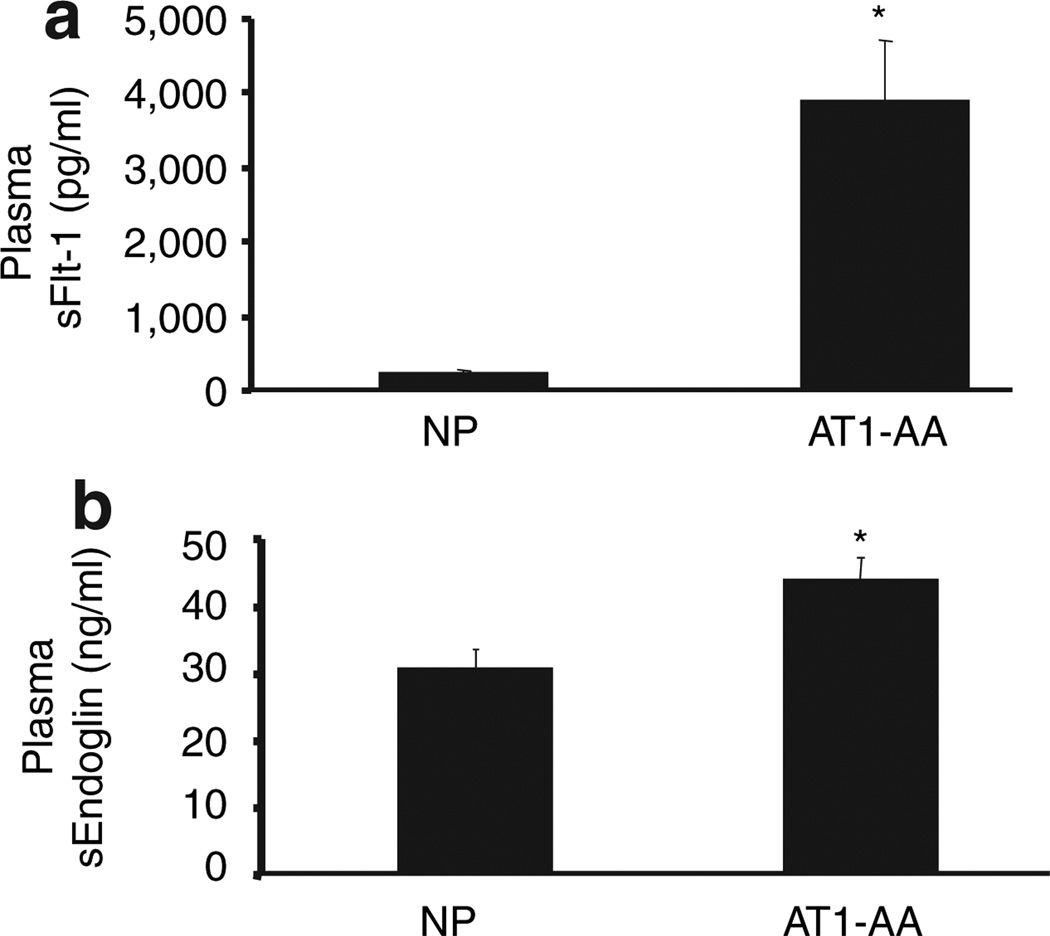

With chronic infusion of rat AT1-AA from day 12 to 19 of gestation, the MAP was significantly higher (114 ± 1 mm Hg) compared to NP controls (97 ± 2 mm Hg) (P < 0.001) (Figure 3). AT1-AA levels increased from 0.88 ± 5 beats per minute (NP) to 14 ± 1 beats per minute (AT1-AA infused) (P < 0.01). sFlt-1 values were significantly (P < 0.001) increased in the AT1-AA induced hypertensive group (3,920 ± 800 pg/ml) compared to the NP control group (246 ± 38) (Figure 4). In addition, sEndoglin increased from 30 ± 2.7 to 44 ± 3.3 pg/ml (P < 0.047) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

All data are expressed as mean ±s.e.m. (a) Changes in mean arterial pressure in response to AT1-AA infusion compared to the normal pregnant control group (NP) (*P < 0.001). (b) AT1-AA increased significantly in response to chronic infusion, indicated by increased beats per minute (bpm) of the cultured rat neonatal cardiomyocyte assay.

Figure 4.

All data are expressed as mean ±s.e.m. (a) Circulating sFlt-1 increased in response to AT1-AA induced hypertension vs. normal pregnant controls. (*P < 0.001). (b) Circulating sEng increased in response to AT1-AA induced hypertension vs. normal pregnant controls. (*P < 0.047).

Placental sFlt-1 and sEng in response to chronic AT 1-AA

Placental explants from NP and AT1-AA infused pregnant rats were cultured overnight and sFlt-1 concentrations were determined from cell culture media. Basal sFlt-1 increased from 2,480 ± 257 (NP) to 3,421 ± 125 pg/ml (AT1-AA). In addition, after 22 h of incubation, sFlt-1 from NP placentas was 2,189 ± 221 (n = 12) compared to 3,369 ± 152 pg/ml (P < 0.0014) (n = 7) from placental explants from AT1-AA induced hypertensive pregnant rats (Figure 5). This response was completely attenuated with AT1-receptor antagonism. Interestingly, there was no difference in sEndoglin secretion from placental explants from NP and AT1-AA infused pregnant rats (33 ± 2.7 vs. 31 ± 3.1 ng/ml).

Figure 5.

Placental sFlt-1 increases in response to AT1-AA infusion compared to normal pregnant control rats (*P < 0.05).

Effect of chronic TNF-α or AT 1-AA on pup and placental weights

As with previous studies from our laboratory,18–21 chronic administration of either TNF-α or the purified rat AT1-AA, no effects on pup or placental weights were seen in pregnant rats. In all groups, average pup weights were 2.2 g and placental weights were 0.56 g whereas average litter sizes were 15 pups per litter.

DISCUSSION

Hypertension in response to placental ischemia is associated with excessive production of inflammatory cytokines, agonistic autoantibodies to the angiotensin II type I receptor, and an imbalance in angiogenic factors (vascular endothelial growth factor/placental growth factor) and antiangiogenic factors (sFlt-1 and sEng).17–24 One mechanism whereby TNF-α mediates hypertension during pregnancy appears to be via production of AT1-AA through activation of the AT1 receptor.18 This study, an extension of latter, in which we demonstrate that chronic, moderate increases in TNF-α, stimulates the overexpression of sFlt-1 during pregnancy. In addition, placental explants collected from TNF-α induced hypertensive pregnant rats, secreted excess sFlt-1 implicating the placenta as one potential source of this antiangiogenic factor. Finally, we have demonstrated that like TNF-α induced hypertension, TNF-α stimulated sFlt-1 can be attenuated by blockade of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Although this study is the first to demonstrate a role for TNF-α to stimulate circulating and placental sFlt-1 it does not identify the cellular source responsible for the sFlt-1 overproduction during pregnancy. Interestingly, although treatment with the AT1-receptor antagonist blocked circulating increases in sFlt-1, in corroboration with what we have previously shown18 AT1-receptor antagonism only blunted the hypertensive response, as well as the placental sFlt-1 production. Although these data indicate the importance of other placental and vascular factors mediating the blood pressure and placental sFlt-1 response in the pathophysiology of hypertension associated with increased TNF-α during pregnancy, they also led us to examine the role of AT1-receptor activation mediated by the AT1-AA as a potential stimulus for excess sFlt-1 and sEndoglin. We found both circulating sFlt-1 and sEndoglin to be significantly elevated in AT1-AA-induced hypertensive pregnant rats and (Figure 4). We also examined the media of placental explants from AT1-AA induced hypertensive pregnant rats and found significant increases in sFlt-1, again indicating the placenta as a potential source of excess sFlt-1. However, when we examined sEng from placental explant media, there was no difference when compared to the media collected from placentas of NP control rats, indicating another cellular source for the sEng production. These data support the hypothesis that chronic immune activation in association with placental ischemia leads to sFlt-1 and sEng overexpression via stimulation of the AT1-receptor possibly by production of the AT1-AA. These studies demonstrate an important interaction between inflammatory and angiogenic markers found to be produced excessively in response to placental ischemia.

Considerable clinical evidence has accumulated that preeclampsia is strongly linked to an imbalance between proangiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in the maternal circulation.3–9 Both plasma and amniotic fluid concentrations as well as placental sFlt-1 mRNA are increased in preeclamptic patients.3–9 Recently, studies have reported that increased sFlt-1 may have a predictive value in diagnosing preeclampsia as concentrations seem to increase before manifestation of overt symptoms (e.g., hypertension, proteinuria).10,12,13 These same clinical findings and imbalances in angiogenic factors were found to be reproducible in the rat model via lentiviral overexpression of sFlt-1.24,25 Following this discovery, other investigators revealed that infusion of a proangiogenic factor (e.g., vascular endothelial growth factor) into pregnant rats would attenuate blood pressure elevations and renal damage observed in pregnant rats overexpressing sFlt-1.26 Thus, these studies suggest that sFlt-1 and alterations in angiogenic factors may contribute to the clinical symptoms observed in preeclampsia. However, their observations did not address the mechanisms whereby sFlt-1 overexpression occurs.

Recent studies in rats by Gilbert et al. and in primates by Makris et al. demonstrate that placental ischemia is an important stimulus for sEng and sFlt-1.24,27 A significant elevation in the placental and peripheral blood mononuclear cell sFlt-1 mRNA expression was noted, translating to a significant elevation in circulating sFlt-1.27 It was these observations that instigated our investigation into the role of inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, as a stimulus for sFlt-1. This is one of the first studies to demonstrate that chronic TNF-α infusion stimulates an increase in circulating sFlt-1 and that treatment with an AT1-receptor antagonist abolishes TNF-α stimulated sFlt-1 production. In addition, we demonstrate placental secretion of sFlt-1 to be enhanced in response to chronic infusion of TNF-α during pregnancy. However, one limitation of the study is that we did not determine a possible cellular source, such as monocytes or lymphocytes, as contributors to sFlt-1 or sEng production.

Previous studies by Zhou et al. demonstrated that human IgG from preeclamptic women injected into pregnant mice increased circulating sFlt-1 and this could be attenuated by a one time administration of an AT1-receptor antagonist.28,29 In addition, placental villous explants incubated with human IgG stimulated sFlt-1. In contrast to Zhou et al., our laboratory administers column purified rat AT1-AA systemically for 7 days into NP rats to induce hypertension which is attenuated with chronic administration of an AT1-receptor antagonist. Nevertheless, in agreement with Zhou et al., we found serum and placental secretion of sFlt-1 to be significantly elevated from AT1-AA induced hypertensive pregnant rats. We also demonstrate a role for the AT1-AA to stimulate circulating sEng, however our data indicates a source other than the placenta for the excess sEng. One potential source could be circulating monocytes or other immune cells.

We have collectively demonstrated that one important ramification of chronic inflammation during pregnancy is stimulation of sFlt-1. In this study, we have shown that circulating and placental sFlt-1 levels are enhanced in response to TNF-α induced hypertension. Both TNF-α induced hypertension and TNF-α stimulated sFlt-1 production were significantly blunted with AT1-receptor blockade, suggesting a role for the AT1-AA as a stimulus for sFlt-1 production. Moreover, in conjunction with studies from Zhou et al., we demonstrate that hypertension in response to the AT1-AA serves as a stimulus for circulating and placental sFlt-1. Although these studies suggest a role for chronic immune activation in stimulating sFlt-1 and sEng in response to placental ischemia, it does not quantify the importance of endogenous TNF-α, AT1-AA, or immune cell activation in mediating sFlt-1 or sEng in response to reductions in uterine perfusion. Future studies are designed to determine the effect of chronic immunosuppression on sFlt-1 and sEng production in response to placental ischemia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL51971 and AHA 0835472N.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Conrad KP, Benyo DF. Placental cytokines and the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1997;37:240–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1997.tb00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granger JP, Alexander BT, Bennett WA, Khalil RA. Pathophysiology of pregnancy-induced hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:178S–185S. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karumanchi SA, Bdolah Y. Hypoxia and sFlt-1 in preeclampsia: the “chicken-and-egg” question. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4835–4837. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karumanchi SA, Maynard SE, Stillman IE, Epstein FH, Sukhatme VP. Preeclampsia: a renal perspective. Kidney Int. 2005;67:2101–2113. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajakumar A, Michael HM, Rajakumar PA, Shibata E, Hubel CA, Karumanchi SA, Thadhani R, Wolf M, Harger G, Markovic N. Extra-placental expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1, (Flt-1) and soluble Flt-1 (sFlt-1), by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in normotensive and preeclamptic pregnant women. Placenta. 2005;26:563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rana S, Karumanchi SA, Levine RJ, Venkatesha S, Rauh-Hain JA, Tamez H, Thadhani R. Sequential changes in antiangiogenic factors in early pregnancy and risk of developing preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2007;50:137–142. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.087700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thadhani RI, Johnson RJ, Karumanchi SA. Hypertension during pregnancy: a disorder begging for pathophysiological support. Hypertension. 2005;46:1250–1251. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000188701.24418.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam C, Lim KH, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors in the pathogenesis and prediction of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2005;46:1077–1085. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000187899.34379.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindheimer MD, Romero R. Emerging roles of antiangiogenic and angiogenic proteins in pathogenesis and prediction of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2007;50:35–36. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herse F, Verlohren S, Wenzel K, Pape J, Muller DN, Modrow S, Wallukat G, Luft FC, Redman CW, Dechend R. Prevalence of agonistic autoantibodies against the angiotensin II type 1 receptor and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 in a gestational age-matched case study. Hypertension. 2009;53:393–398. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.124115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benyo DF, Smarason A, Redman CW, Sims C, Conrad KP. Expression of inflammatory cytokines in placentas from women with preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2505–2512. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kupferminc MJ, Peaceman AM, Wigton TR, Rehnberg KA, Socol ML. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is elevated in plasma and amniotic fluid of patients with severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:1752–1757. discussion 1757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Visser W, Beckmann I, Bremer HA, Lim HL, Wallenburg HC. Bioactive tumour necrosis factor alpha in pre-eclamptic patients with and without the HELLP syndrome. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:1081–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1994.tb13587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallukat G, Homuth V, Fischer T, Lindschau C, Horstkamp B, Jüpner A, Baur E, Nissen E, Vetter K, Neichel D, Dudenhausen JW, Haller H, Luft FC. Patients with preeclampsia develop agonistic autoantibodies against the angiotensin AT1 receptor. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:945–952. doi: 10.1172/JCI4106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dechend R, Homuth V, Wallukat G, Müller DN, Krause M, Dudenhausen J, Haller H, Luft FC. Agonistic antibodies directed at the angiotensin II, AT1 receptor in preeclampsia. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006;13:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dechend R, Müller DN, Wallukat G, Homuth V, Krause M, Dudenhausen J, Luft FC. Activating auto-antibodies against the AT1 receptor in preeclampsia. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaMarca BD, Gilbert J, Granger JP. Recent progress toward the understanding of the pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2008;51:982–988. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.108837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaMarca B, Wallukat G, Llinas M, Herse F, Dechend R, Granger JP. Autoantibodies to the angiotensin type I receptor in response to placental ischemia and tumor necrosis factor alpha in pregnant rats. Hypertension. 2008;52:1168–1172. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.120576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaMarca BB, Bennett WA, Alexander BT, Cockrell K, Granger JP. Hypertension produced by reductions in uterine perfusion in the pregnant rat: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Hypertension. 2005;46:1022–1025. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000175476.26719.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keiser SD, Veillon EW, Parrish MR, Bennett W, Cockrell K, Fournier L, Granger JP, Martin JN, Jr, Lamarca B. Effects of 17-hydroxyprogesterone on tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced hypertension during pregnancy. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:1120–1125. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaMarca B, Parrish M, Ray LF, Murphy SR, Roberts L, Glover P, Wallukat G, Wenzel K, Cockrell K, Martin JN, Jr, Ryan MJ, Dechend R. Hypertension in response to autoantibodies to the angiotensin II type I receptor (AT1-AA) in pregnant rats: role of endothelin-1. Hypertension. 2009;54:905–909. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dechend R, Gratze P, Wallukat G, Shagdarsuren E, Plehm R, Bräsen JH, Fiebeler A, Schneider W, Caluwaerts S, Vercruysse L, Pijnenborg R, Luft FC, Müller DN. Agonistic autoantibodies to the AT1 receptor in a transgenic rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2005;45:742–746. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000154785.50570.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dragun D, Müller DN, Bräsen JH, Fritsche L, Nieminen-Kelhä M, Dechend R, Kintscher U, Rudolph B, Hoebeke J, Eckert D, Mazak I, Plehm R, Schönemann C, Unger T, Budde K, Neumayer HH, Luft FC, Wallukat G. Angiotensin II type 1-receptor activating antibodies in renal-allograft rejection. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:558–569. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilbert JS, Babcock SA, Granger JP. Hypertension produced by reduced uterine perfusion in pregnant rats is associated with increased soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 expression. Hypertension. 2007;50:1142–1147. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.096594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, Libermann TA, Morgan JP, Sellke FW, Stillman IE, Epstein FH, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:649–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Zhang Y, Ying Ma J, Kapoun AM, Shao Q, Kerr I, Lam A, O’Young G, Sannajust F, Stathis P, Schreiner G, Karumanchi SA, Protter AA, Pollitt NS. Recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor 121 attenuates hypertension and improves kidney damage in a rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2007;50:686–692. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.092098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makris A, Thorton T, Thompson J, Thompson S, Martin R, Ogle R, Waugh R, Mackenzie P, Kirwan P, Hennessey A. Uteroplacental ischemia results in proteinuric hypertension and elevated sFLT-1. Kidney Int. 2007;10:959–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou CC, Ahmad S, Mi T, Abbasi S, Xia L, Day MC, Ramin SM, Ahmed A, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Autoantibody from women with preeclampsia induces soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 production via angiotensin type 1 receptor and calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T-cells signaling. Hypertension. 2008;51:1010–1019. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.097790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou CC, Zhang Y, Irani RA, Zhang H, Mi T, Popek EJ, Hicks MJ, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibodies induce pre-eclampsia in pregnant mice. Nat Med. 2008;14:855–862. doi: 10.1038/nm.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]