History

A 19-year-old Asian male presented with facial pain of 2 1/2 months duration that was believed to be dental-related. Root canal therapy and multiple extractions failed to alleviate the patient’s discomfort. Subsequent CT images demonstrated an extensive mass in the left maxillary sinus.

Radiographic Features

Computed tomography of the paranasal sinuses using Landmarx protocol was performed using axial images without the administration of intravenous contrast material. Axial, sagittal and coronal reformatted images of the paranasal sinuses were obtained. CT images revealed opacification of the left maxillary sinus by a lesion with a calcific rim. There were additional areas of punctate calcifications within the lesion which represented matrix mineralization (Fig. 1). The lesion induced moderate expansile remodeling of the left maxillary sinus and mucosal thickening surrounding the lesion (Fig. 2). There were additional mucosal thickenings of the nasal cavity, ethmoid sinus, and left frontal sinus (Fig. 3). The left osteomeatal complex was also obstructed by a soft tissue density.

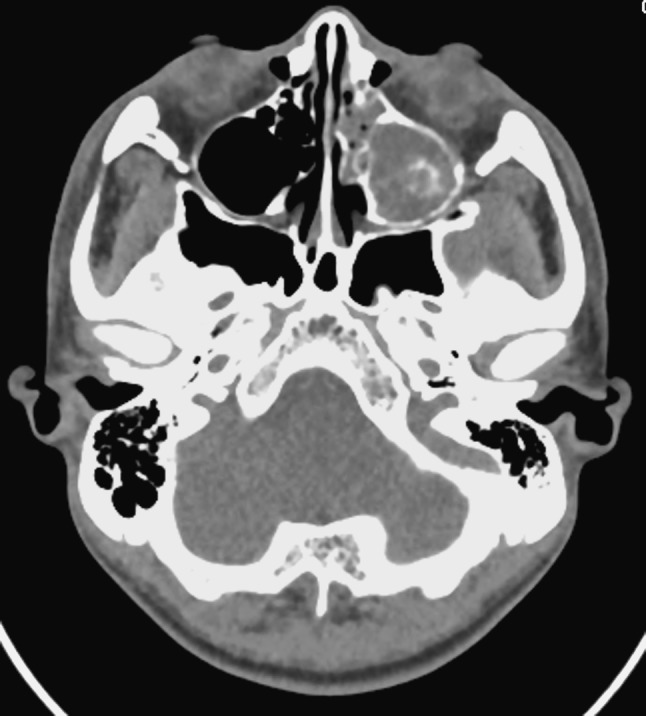

Fig. 1.

Axial CT soft tissue window demonstrating a mass with a peripheral rim of calcification opacifying the left maxillary sinus. Central calcification representing matrix mineralization is evident

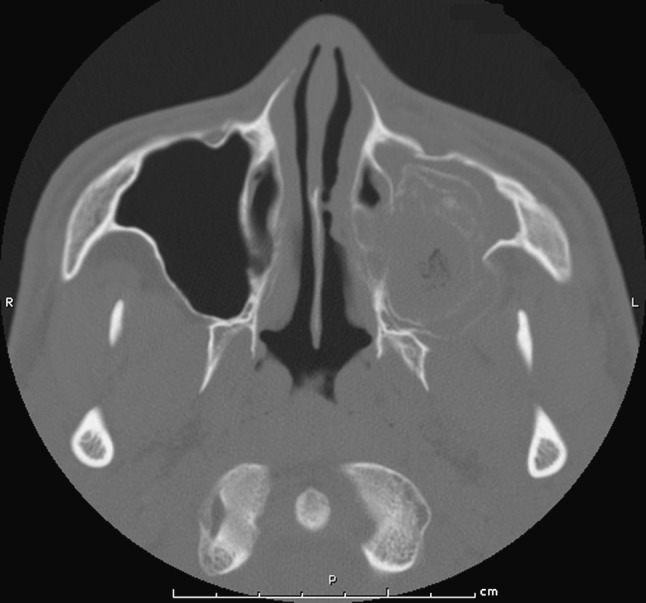

Fig. 2.

Axial CT with bone window demonstrating moderate expansile remodeling of the involved maxillary sinus

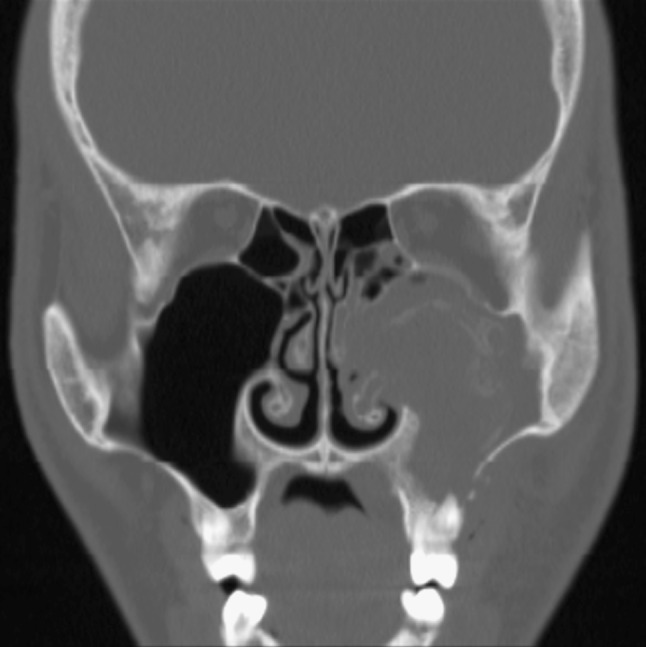

Fig. 3.

Coronal CT with bone window demonstrating involvement of the maxillary alveolar process with extension to the maxillary sinus, nasal cavity, and ethmoid sinus. Prominent mucosal thickening of the maxillary sinus surrounding the lesion and the adjacent nasal cavity and ethmoid sinus is noted

Diagnosis

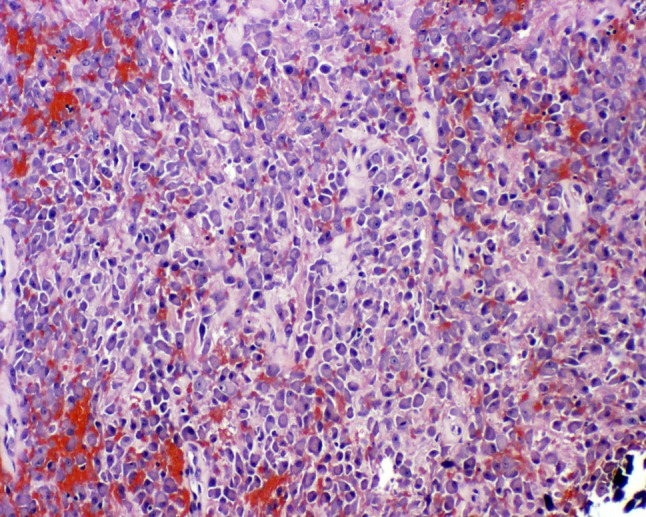

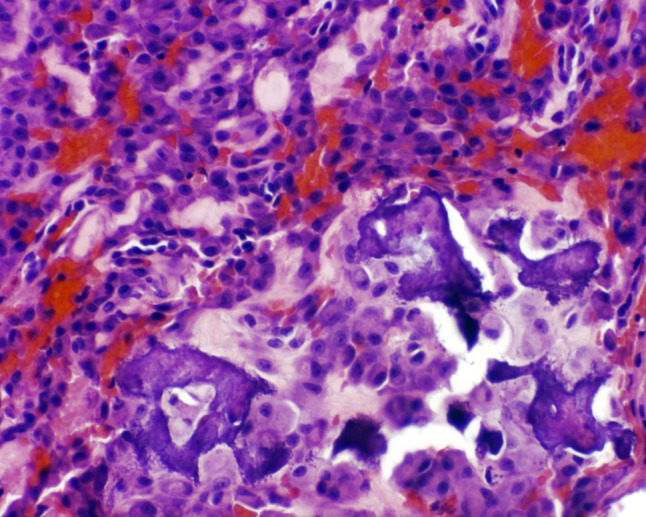

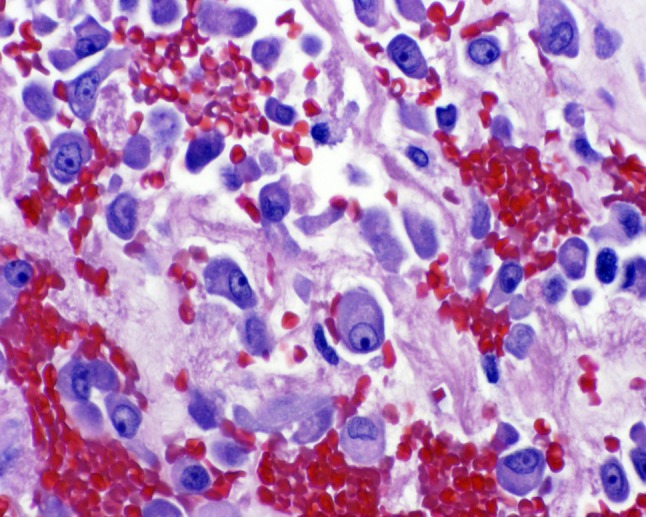

The hematoxylin and eosin-stained surgical specimens from the left maxillary sinus and alveolus demonstrated irregular deposits of osteoid and trabeculae of woven bone with adjacent and peripherally placed islands of epithelioid osteoblasts (Fig. 4). Solid sheets of epithelioid cells were present within the intertrabecular areas (Fig. 5) and scattered deposits of immature “blue bone” were identified as admixed with the neoplastic cells (Fig. 6). The epithelioid cells displayed an eccentrically-placed nucleus and abundant eosinophilic appearing cytoplasm, thereby resembling a plasma cell. Prominent nucleoli, an occasional cytoplasmic inclusion and mild cellular pleomorphism also characterized the lesional cells (Fig. 7). While rare mitotic figures were present, no atypical mitotic figures were identified. There was no evidence of obvious tumor invasion of host lamellar bone.

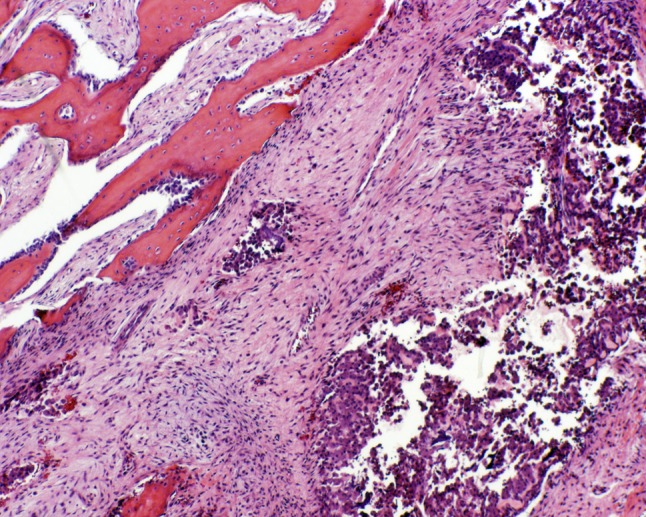

Fig. 4.

Irregular deposits of osteoid and trabeculae of woven bone are rimmed by epithelioid osteoblasts

Fig. 5.

Solid sheets of epithelioid cells are present within the intertrabecular areas

Fig. 6.

Focal deposit of immature “blue bone” admixed with the neoplastic cells

Fig. 7.

Epithelioid osteoblasts possess prominent nucleoli and demonstrate mild pleomorphism

Discussion

Epithelioid osteoblastoma (EO) is a rare histologic variant of osteoblastoma comprised of numerous large epithelioid osteoblasts that rim the periphery of bony trabeculae and are organized into large sheets within intertrabecular areas [1]. EO is also referred to as aggressive osteoblastoma due to its propensity for locally-invasive growth and high rate of recurrence [2–4]. Previously, the term “malignant osteoblastoma” was utilized to denote this lesion; however, none of these tumors have been reported to have metastasized and, thus, the preferable term is aggressive osteoblastoma [3].

Osteoblastomas are more commonly seen in males with a 2.5:1 ratio when compared to prevalence in females. This benign bone-forming neoplasm typically affects patients between the ages of 10–30 years and is most commonly found in the vertebral column and long bones [5, 6]. When present in the head and neck, the most common site of involvement is the gnathic skeleton with the mandible being affected 2–3 times more frequently than the maxilla. The majority of mandibular osteoblastomas arise within the body of the mandible [7]. Clinically, aggressive osteoblastomas demonstrate rapid growth and are locally destructive, and present as expansile osteolytic lesions with focal radiopacities that can be clinically and radiographically mistaken for osteosarcoma. Jaw lesions often present with significant pain and may induce tooth mobility, thus leading to misdiagnosis of early lesions as a dental-related infection or osteomyelitis [2, 4].

The histologic differential diagnosis for EO includes conventional osteoblastoma (CO) and low-grade osteosarcoma (LG-OS). The hallmark histologic feature of EO is the presence of plump epithelioid osteoblasts arranged in large sheets encompassing intertrabecular spaces as well as lining the periphery of lesional bony trabeculae. The epithelioid osteoblasts typically have a plasmacytoid appearance with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, well-defined cell borders, and eccentric round to oval nuclei with occasional nucleoli. The presence of these epithelioid osteoblasts is the primary criterion utilized to distinguish CO from EO. Examination of the interface between the lesion and host cortical bone is important in differentiating between EO and LG-OS. Tumor infiltration and entrapment of host bone indicates a more ominous pathologic process and is suggestive of LG-OS. While mild cellular pleomorphism and a low mitotic rate (less that 4 mitotic figures for 20 high-power fields) are acceptable findings in EO, the presence of atypical mitotic figures and/or chondroid differentiation (features of osteosarcoma) are absent in EO and favor the diagnosis of LG-OS [2–4, 8].

The radiologic differential diagnosis for osteoblastoma includes ossifying fibroma, chondrosarcoma, and osteosarcoma. The lesion typically presents as a radiolucent, well-circumscribed, expansile mass with focal calcification [1]. However, EO has also been reported to present with a more aggressive radiologic appearance. Occasionally, the locally aggressive lesion may present as a poorly-circumscribed, bone-producing mass demonstrating cortical destruction and an associated soft tissue mass, features of which are worrisome for malignancy [1, 8, 9]. Histologic examination of the tissue is required for definitive diagnosis.

Due to the aggressive behavior and propensity for recurrence associated with EO, the recommended treatment for these lesions is surgical resection with wide margins and subsequent reconstruction. Adjuvant radiation and/or chemotherapy are contraindicated [1, 2, 4, 5]. The patient in this case underwent resection of the lesion and currently has an oral-antral fistula. He is being closely followed with serial exams and imaging studies to evaluate for recurrence. A separate reconstruction procedure will be performed, providing the patient does not exhibit signs of recurrence.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as official or representing the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense. I certify that all individuals who qualify as authors have been listed; each has participated in the conception and design of this work, the writing of the document, and the approval of the submission of this version; that the document represents valid work; that if we used information derived from another source, we obtained all necessary approvals to use it and made appropriate acknowledgements in the document; and that each takes public responsibility for it.

We are military service members. This work was prepared as part of our official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that ‘Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.’ Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a United States Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties.

References

- 1.Gnepp DR. Diagnostic surgical pathology of the head and neck. 2. Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier; 2009. pp. 732–734. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vigneswaran N, Fernandes R, Rodu B, et al. Aggressive osteoblastoma of the mandible closely simulating calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor. Pathol Res Pract. 2001;197:569–576. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorfman H, Weiss S. Borderline osteoblastic tumors: problems in the differential diagnosis of aggressive osteoblastoma and low-grade osteosarcoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1984;1:215–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrington C, Accurso B, Kalmar JR, et al. Aggressive osteoblastoma of the maxilla: a case report and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2011;5:165–170. doi: 10.1007/s12105-010-0234-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lypka MA, Goos RR, Yamashita D-DR, Melrose R. Aggressive osteoblastoma of the mandible. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37:675–678. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malcolm AJ, Schiller AL, Schneider-Stock R. Osteoblastoma. In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. pp. 262–263. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jundt G, Bertoni F, Unni KK, et al. Osteoblastoma. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, et al., editors. World Health Organization classifications of tumours: pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohkubo T, Hernandez JC, Ooya K, Krutschkoff DJ. Aggressive osteoblastoma of the maxilla. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filippi RZ, Swee RG, Unni KK. Epithelioid multinodular osteoblastoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1265–1268. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31803402e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]