Abstract

The hallmark of the histology of epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma (EMC) is the presence of a regular repetitive mixture of bilayered duct-like structures with an outer layer of myoepithelial cells and inner ductal epithelial cells. Clear cell change in the myoepithelial component is common, but clearing of both cell types, giving an impression of a monocellular neoplasm, is rare. A parotid biopsy was received from an 83-year-old male and subject to routine histologic processing for conventional staining and immunohistochemistry. The encapsulated tumour was composed of sheets of PAS/diastase negative clear cells, separated by fibrous septae. The clear myoepithelial cells were positive for S-100 protein, SMA, and p63 and negative for CK19 and surrounded CK19-positive luminal cells. It is important to utilise immunohistochemistry to differentiate this tumour from others with a similar histologic pattern. Information about the behaviour of the double-clear EMC is limited since there are few cases reported.

Keywords: Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, Salivary gland tumour, Clear cell tumours

Introduction

Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma (EMC) is a rare malignant salivary gland neoplasm accounting for less than 1% of all salivary gland tumours [1]. This tumour was originally described by Donath et al. [2] and later reviewed by other investigators including Seethala et al. [3] and Corio et al. [4]. EMC is defined as a malignant tumour with biphasic morphology with clear myoepithelial cells surrounding small lumina or ducts, which are lined by ductal epithelial cells [5]. Due to this tubular morphology, it has been postulated that EMC is derived from the intercalated ducts of salivary glands. Although classified as a malignant neoplasm, EMC is typically a low-grade tumour that occurs mainly in the parotid gland (62.1%) [3], although it can also occasionally arise from the submandibular gland and minor salivary glands.

The morphology of EMC can be variable and the lesion may be arranged in lobular, solid, cystic, or papillary architectural patterns, but the hallmark of the histology is the presence of bilayered duct-like structures with an outer layer of myoepithelial cells. Cases of a dedifferentiated variant with cellular atypia have been reported with concurrent poor prognosis [3, 6]. Seethela et al. [3] described two other novel variations, a double-clear cell variant and a variant with myoepithelial anaplasia. These morphologic disparities cause difficulty in diagnosis as the patterns can overlap with those seen in other salivary gland tumours. Immunohistochemistry may be a useful tool in separating EMC from other salivary tumours; however, it often is diagnostically challenging to correctly diagnose EMC with differentiation between the variants. Whether the histologic variations of EMC have any clinical implication is too early to tell, as only two cases have previously been reported.

The purpose of this paper is to report the rare double-clear variant of EMC arising in the parotid gland and to highlight the difficulty in identifying this tumour.

Case Report

An 83-year-old man was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon with a painless swelling in the right subauricular region of unknown duration. Other than cardiovascular disease, he had no known illnesses. Upon examination, his facial movement was intact and there was a mobile swelling in the right subauricular region. The patient was sent for fine needle aspiration cytology, which was reported elsewhere as pleomorphic adenoma. Imaging was performed and the patient underwent a superficial parotidectomy with removal of the parotid duct and accessory parotid gland. The gross appearance was a brownish white mass with encapsulation, 15 × 9 × 6 mm, surrounded by adipose tissue and lobules of salivary gland.

Microscopic Findings from the Surgical Specimen

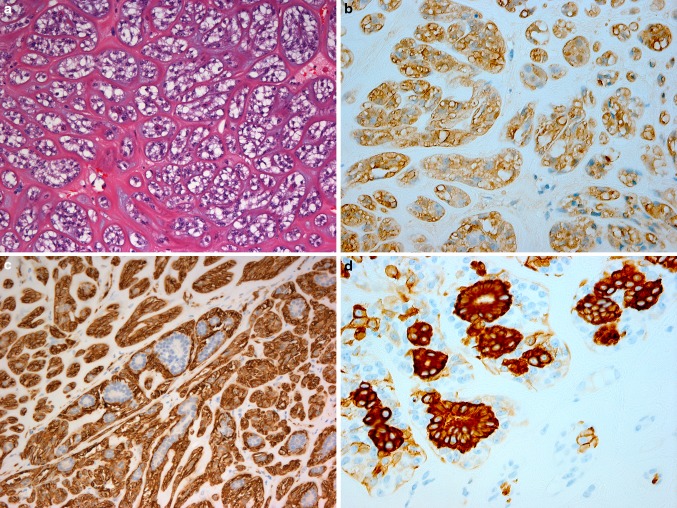

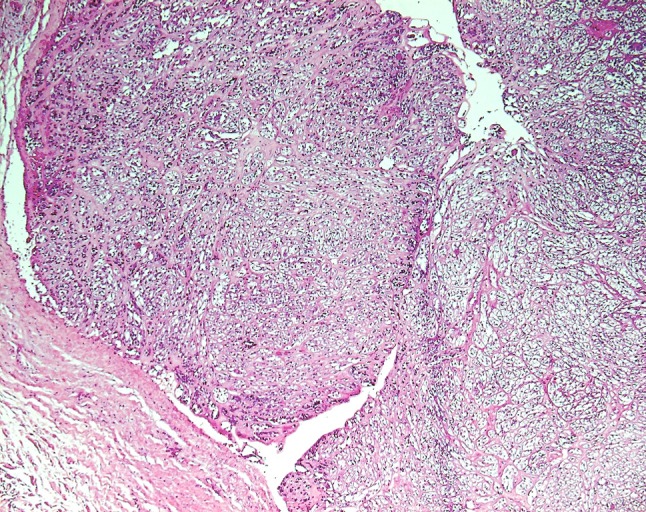

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections revealed that the tumour was circumscribed and well-encapsulated by thick fibrous tissue. It was composed of islands, sheets, and strands of cells all showing abundant clear cytoplasm (Fig. 1). Eosinophilic hyalinised tissue was present between the clear cells forming thick bands as well as thin septae (Fig. 2a). There was variation in the size and shape of the nuclei, with many showing a prominent vesicular nucleolus. Occasional duct-like structures and blood vessels were present. Mitotic activity was minimal. The clear cells were repeatedly negative in periodic acid-Schiff-stained sections, with and without diastase. Immunohistochemistry showed strong staining of the lesional clear cells with S-100 protein (Fig. 2b). The peripheral (myoepithelial) cells were smooth muscle actin (SMA) positive (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 1.

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections showing sheets and strands of large clear cells with a well-encapsulated margin

Fig. 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections showing hyalinised strands separating the clear cells (a). Immunohistochemical staining showing S-100 protein positivity of the clear lesional (myoepithelial and luminal) cells (b), SMA positivity of the clear myoepithelial cells, surrounding the luminal cells (c) and CK19 positivity of the clear luminal cells, surrounded by non-stained myoepithelial cells (d)

With most areas showing clear myoepithelial cells with a minimal ductal component, coupled with surrounding encapsulation, a working diagnosis of clear cell myoepithelioma was made. However, due to the rarity of these types of lesions further opinions were sought (from CA and PS) and further immunohistochemistry undertaken.

Aggregates of 2–5 cells, which were positive for pan-cytokeratin and CK19 (Fig. 2d) were seen scattered diffusely throughout the specimen with one focal area showing aggregates of these cells with distinct duct-like structures. Only with immunohistochemistry could the myoepithelial cell and ductal epithelial relationship and distinction be visualized clearly and even then the distribution was sparse. This was due to clear cell change occurring in both luminal and myoepithelial cells, thereby creating a false solid architecture. The solid growth pattern of this particular lesion emphasises the difficulty in distinguishing and recognising the biphasic component that characterizes this entity. Subsequent immunostains performed, including p63 and epithelial markers, confirmed these findings.

With this additional information the diagnosis of epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma double-clear variant was made and conveyed to the surgeon, who carried out further surgery with a wider excision margin. The patient has been disease free for the past 2 years, since the additional surgery.

Discussion

EMC is a relatively rare low-grade malignant salivary gland tumour. More than 300 cases have been described since EMC was first reported [3] and it has a wider histomorphology than was previously recognised. EMC is a biphasic tumour, comprising a regular repetitive mixture of two cells type, myoepithelial cells and ductal epithelial cells [7]. Immunohistochemistry is useful in recognising the two cell types. The outer myoepithelial cells express p63, which is generally agreed to be a sensitive myoepithelial cell marker in typical EMC [3, 4, 8]. A traditional marker of myoepithelial cells is SMA, a good indicator of their smooth muscle characteristics. Other myoepithelial markers, such as S100, calponin and CK14 have been used, although they are less informative than p63 and SMA [3, 8]. The inner luminal epithelial cells are negative for SMA and positive with cytokeratin markers, e.g. AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2 [8]. Pancytokeratin is not specific, but is considered to be reliable. In this case, SMA, S100, and p63 were used in assessing the myoepithelial component and a keratin stain, specifically CK19, to indicate epithelial luminal cells. Roy et al. [8]. recommended that dedifferentiated EMC may warrant a more extensive immunohistochemistry panel to fully characterise the disease.

Differentiation from one or both of the EMC cell types gives rise to the divergent histologic spectrum that is observed in these lesions. Clear cell change of the myoepithelial component is observed in almost 80% of EMC [9]. However, Seethala et al. [3] observed two cases of EMC where the columnar or stratified luminal epithelial cells also showed clearing. Clearing of both cell types gives an impression of a monocellular neoplasm composed of clear myoepithelial cells, as in our case. Coupled with the encapsulation of the tumour mass and the lobular pattern, is it not unexpected that the diagnosis of pleomorphic adenoma or myoepithelioma has been given to many of these tumours.

Before the definitive diagnosis can be made, several other tumours that can contain clear cells should be considered. For example, clear cell carcinoma must be considered in the differential, as well as the clear cell variants of several salivary gland neoplasms, including acinic cell carcinoma, oncocytoma/oncocytic carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and myoepithelioma or myoepithelial carcinoma. Metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma is also in the differential. The observation of a distinct biphasic pattern, the clear cell morphology and known preponderance for occurring in the parotid (60–80%) [10], all of which fit with the current case, helped distinguish EMC from the rest, along with the histochemical and immunohistochemical findings. In this case, the negative staining with PAS/diastase and immunoreactivity with S-100 protein and SMA meant that most other diagnoses were excluded. It is not understood why the clear cells in this case, and in the two cases described by Seethala et al. [3], were repeatedly PAS negative. Particular care needs to be taken when only an incisional biopsy is available. In these circumstances, the importance of integrating the clinical history, histologic features, and immunophenotypic profile is undeniable. One should also consider other variants of EMC, such as dedifferentiated EMC, oncocytic EMC, EMC arising from pleomorphic adenoma, and EMC with myoepithelial hyperplasia [3].

The initial working diagnosis in this case, based on H&E stains and the encapsulated nature of the lesion, was clear cell myoepithelioma. It was only after careful examination of the immunohistochemical profile and appreciation of this novel variant that a diagnosis of double-clear variant of EMC was made. We believe that immunohistochemistry is required to confidently diagnose this variant. While most EMC are not encapsulated, the double-clear cell variant may be [3]. Provided that there is no or minimal cellular atypia, the diagnosis of double-clear variant of EMC can be made upon fulfilling these criteria. Sebaceous differentiation of the double-clear variant was emphasized by Cheuk and Chan [9], however, we did not observe any sebaceous change in our case. The prognosis of the double-clear EMC variant appears to be similar to conventional EMC, but this observation is based on only the few cases reported.

Other EMC variants that have been reported are the oncocytic variant where oncocytic change is observed mainly in the luminal cells alone or in both the luminal and abluminal cells [9, 11]. This variant is at the opposite end of the spectrum in comparison to the double-clear variant, where it is the myoepithelial cells that normally undergo clear cell changes. A variant with ancient change has been reported where the myoepithelial component in EMC exhibited marked pleomorphism with occasional nuclei showing enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei without increased mitotic activity. The behaviour of both these variants is unknown since so few cases have been reported, although those reported to date have behaved in a similar manner to conventional EMC [3, 9].

The recurrence rate of typical EMC is between 35 and 40%, with low risk of metastasis [3, 5]. However, EMC may change their features with progression towards a more malignant phenotype and this is associated with a poorer prognosis. Two forms of progression of EMC are observed [9]; the first is the progression to high-grade myoepithelial carcinoma characterized by overgrowth of the myoepithelial component with nuclear anaplasia. This has been reported as EMC with myoepithelial anaplasia or myoepithelial carcinoma arising from EMC. Fonseca and Soares [12] showed that atypia of more than 20% of lesional cells was predictive of poor outcome. The second form of progression is dedifferentiation into high-grade carcinoma without evidence of myoepithelial differentiation [13] and is known as dedifferentiated EMC [14]. It is thought that the ductal component transforms into a high-grade carcinoma with high mitotic activity and areas of necrosis [3]. The prognosis is generally poor in this type of EMC [15]. The use of immunohistochemistry may be helpful in identifying the cell components in both types of high-grade carcinoma; however, the ability to express proteins usually seen in EMC may be lost with loss of differentiation [8]. Due to this fact, the criteria for defining dedifferentiated EMC can be difficult. It has been suggested that both dedifferentiated EMC and EMC with myoepithelial anaplasia be classified as EMC with high-grade transformation and that they should be treated more radically compared to typical low-grade EMC [16].

In summary, we report a case of a double-clear EMC variant that developed in the parotid salivary gland. This case report is only one of a very small number of total reports of this variant of EMC. It is important to utilise immunohistochemistry to differentiate this tumour from pleomorphic adenoma and myoepthelioma, for which it can be mistaken, due to the similarity of the histologic pattern. Although appearing to have a similar outcome to typical EMC, information about the behaviour of the double-clear variant of EMC is limited since there are so few cases reported.

References

- 1.Ellis GL. Tumors of the salivary glands. AFIP Atlas of tumor pathology, series 4, Fasc 9. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donath K, Seifert G, Schmitz R. Zur diagnose und ultrastruktur des tubulaeren speichelgangkarzinoms epithelial/myoepitheliales shaltstueckkarzinom. Virchows Arch A. 1972;356:10–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seethala R, Barnes L, Hunt JL. Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma: a review of the clinicopathologic spectrum and immunophenotypic characteristics in 61 tumors of the salivary glands and upper aerodigestive tract report and review. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:44–57. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213314.74423.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chorio RL, Sciubba JJ, Brannon RB, Batsakis JG. Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of intercalated duct origin. A clinicopathologic and ultrastructural assessment of sixteen cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;53:280–287. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fonseca I, Soares J, et al. Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, et al., editors. World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 225–226. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kusafuka K, Takizawa Y, Ueno T, Ishiki H, Asano R, Kamijo T, et al. Dedifferentiated epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland: a rare case report of immunohistochemical analysis and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seifert G, Donath K. Hybrid tumours of salivary glands. Definition and classification of five rare cases. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1996;32B:251–259. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(95)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy P, Bullock MJ, Perez-Ordoez B, Dardick I, Weinreb I. Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma with high grade transformation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1258–1265. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e366d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheuk W, Chan JKC. Advances in salivary gland pathology. Histopathology. 2007;51:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters P, Repanos C, Earnshaw J, Stark P, Burmeister B, McGuire L, Jeavons S, Coman WB. Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of tongue base: a case for case-report and review of literature. Head Neck Oncol. 2010;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savera AT, Salama ME. Oncocytic epithelial–myoepithelial carcinoma of the salivary gland: an underrecognized morphologic variant. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(Suppl. 1):217A. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fonseca I, Soares J. Epithelial–myoepithelial carcinoma of the salivary glands. A study of 22 cases. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;422:389–396. doi: 10.1007/BF01605458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fonseca I, Soares J. Epithelial–myoepithelial carcinomas [letter;comment] Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;101:242. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/101.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato K, Ueda Y, Sakurai A, Ishikawa Y, Kaji S, Nojima T, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the maxillary sinus with gradual histologic transformation to high-grade adenocarcinoma: a comparative report with dedifferentiated carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2006;448:204–208. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-0054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alos L, Carrillo R, Ramos J, Baez JM, Mallofre C, Fernandez PL, et al. High-grade carcinoma component in epithelial–myoepithelial carcinoma of salivary glands clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and flow-cytometric study of three cases. Virchows Arch. 1999;434:291–299. doi: 10.1007/s004280050344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagao T, Gaffey TA, Kay PA, Unni KK, Nascimento AG, Sebo TJ, et al. Dedifferentiation in low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the parotid gland. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:10. doi: 10.1053/S0046-8177(03)00418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]