Background: Surfactant protein D (SP-D) exists in bladder urothelium.

Results: SP-D decreased uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) adherence to bladder cells and UPEC-induced cytotoxicity both by direct interaction with UPEC and by competing with FimH, a lectin on UPEC, for uroplakin Ia binding.

Conclusion: SP-D protects the urothelium against UPEC infection.

Significance: This report suggests a possible function of SP-D in urinary tract.

Keywords: Bacterial Adhesion, Escherichia coli, Infectious Diseases, Innate Immunity, Surfactant Protein D, FimH, Urinary Tract Infection, Uropathogenic Escherichia coli, Uroplakin

Abstract

The adherence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) to the host urothelial surface is the first step for establishing UPEC infection. Uroplakin Ia (UPIa), a glycoprotein expressed on bladder urothelium, serves as a receptor for FimH, a lectin located at bacterial pili, and their interaction initiates UPEC infection. Surfactant protein D (SP-D) is known to be expressed on mucosal surfaces in various tissues besides the lung. However, the functions of SP-D in the non-pulmonary tissues are poorly understood. The purposes of this study were to investigate the possible function of SP-D expressed in the bladder urothelium and the mechanisms by which SP-D functions. SP-D was expressed in human bladder mucosa, and its mRNA was increased in the bladder of the UPEC infection model in mice. SP-D directly bound to UPEC and strongly agglutinated them in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Co-incubation of SP-D with UPEC decreased the bacterial adherence to 5637 cells, the human bladder cell line, and the UPEC-induced cytotoxicity. In addition, preincubation of SP-D with 5637 cells resulted in the decreased adherence of UPEC to the cells and in a reduced number of cells injured by UPEC. SP-D directly bound to UPIa and competed with FimH for UPIa binding. Consistent with the in vitro data, the exogenous administration of SP-D inhibited UPEC adherence to the bladder and dampened UPEC-induced inflammation in mice. These results support the conclusion that SP-D can protect the bladder urothelium against UPEC infection and suggest a possible function of SP-D in urinary tract.

Introduction

Urinary tract infection (UTI)3 is one of the most common infectious diseases in humans (1–4). The bladder is the primary site of infection in about 95% of all UTIs (4). Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) is the most frequent pathogen of UTI. The binding of UPEC to the host urothelial surface through various fimbrial adhesins is the first step for establishing UPEC infection (1, 2). Type 1 fimbriae and P fimbriae are known as adhesins associated with UPEC (2, 3). Type 1 fimbriae are expressed by the majority of UPEC strains. P fimbriae are considered to play a critical role in upper UTI infections (3).

Urothelium is a stratified epithelium and covers the luminal surface of bladder (5, 6). The apical plasma membrane of urothelial superficial cells, called umbrella cells, is covered by urothelial plaque. The urothelial plaque, which corresponds to a specialized plasma membrane at the lumenal surface of urothelial cells, consists of four membrane proteins, the uroplakins (UPs) Ia, Ib, II, and IIIa (5, 6). UPIa and UPIb possess four transmembrane domains, and UPII and UPIIIa possess a single transmembrane domain. UPII and UPIIIa form heterodimeric complexes with UPIa and UPIb, respectively. UPIa is expressed on the cell surface only when it forms a heterodimeric complex with UPII (5). This unique membrane structure functions as a permeability barrier between blood and urine (6). UPEC takes advantage of UPIa, a glycoprotein expressed on the bladder urothelium. In fact, UPIa plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of UPEC infection by serving as a receptor for FimH, the adhesive subunit at the tip of type1 fimbriae expressed by UPEC (7–9). FimH recognizes terminal mannose units of UPIa. Thus, the binding of UPEC via FimH to UPIa is the first step of UPEC infection.

Surfactant protein D (SP-D) plays important roles in the innate immunity of the lung (10–12). This protein is a member of the collectin subgroup of the C-type lectin superfamily that also includes surfactant protein A (SP-A) and mannose-binding lectin (13, 14). The structure of the collectin is characterized by four distinct domains: 1) an N terminus involved in interchain disulfide bonding, 2) a collagen-like domain, 3) a neck domain, and 4) a carbohydrate recognition domain (13, 14). SP-D exhibits a cruciform structure consisting of four trimeric subunits (15, 16). SP-D has important functions in protecting the lung from microbial infections and inflammation. SP-D-null mice infected with group B Streptococcus or Haemophilus influenzae by intratracheal instillation show increased inflammation and inflammatory cell recruitment in the lung (17). SP-D has been shown to increase calcium-dependent uptake of E. coli by neutrophils (18) and agglutinate the bacteria (19). SP-D is also reported to be expressed in the mucosal membrane of human tissues including the salivary gland, gastrointestinal tract, testis, prostate, cervix, heart, kidney, pancreas, and bladder (20–22). However, the functions of SP-D in the non-pulmonary tissues are poorly understood. Because microorganisms are easily able to invade the body through the urinary tract, it is possible that SP-D protects the bladder against microbes. Because SP-D, as well as FimH, prefers to bind mannosyl ligands, we hypothesized that SP-D binds to UPIa and inhibits the FimH binding to the urothelium.

The purposes of this study were to investigate the possible role of SP-D expressed in the bladder and the mechanisms by which SP-D functions. Thus, we determined whether SP-D directly binds UPEC and agglutinates the bacteria and whether SP-D affects adherence of UPEC to the bladder urothelium and the bacterium-induced cytotoxicity. We then examined whether SP-D directly interacts with UPIa and competes with FimH for UPIa binding and investigated the protective roles of SP-D against UPEC in vivo. We show, from the in vitro and the in vivo data, that SP-D protects the bladder urothelium against UPEC infection both by direct interaction with the bacteria and by competing with FimH for UPIa binding. Hence, this report suggests a possible function of SP-D in urinary tract.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Recombinant SP-D

The 1.181-kb cDNA for human SP-D was inserted into pEE14 plasmid vector, and recombinant human SP-D was expressed in CHO-K1 cells using the glutamine synthetase gene amplification system and purified using a mannose-Sepharose 6B column as described previously (23–25). The endotoxin content in the SP-D preparation was <0.3 pg/μg of protein when determined by Limulus amebocyte assay. Recombinant human SP-D was highly oligomeric (molecular mass of ∼5 MDa) by gel filtration chromatography (25). Electron microscopy indicated that SP-D forms a cruciform dodecamer and a multimerized oligomer, which is the slightly predominant form of SP-D (25).

Preparation of Bacteria

Uropathogenic UPEC strain J96, which expresses type 1 fimbrial adhesin, was obtained from ATCC. J96 was cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and washed with PBS. The concentration of bacterial suspension was determined by measuring absorbance at 600 nm. For preparing UV-killed bacteria, the cultured medium was UV-irradiated for 5 min. The bacteria were then washed and suspended with PBS. The suspension was subdivided into small volumes in tubes and stored at −80 °C. The thawed bacterial stocks were used for the experiments. For preparation of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-expressing J96 strain, a pGEX6-EGFP vector was transformed into J96 by electroporation using an Electro Cell Manipulator 600/630 (BTX) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The EGFP-expressing J96 was cultured in LB broth overnight at 37 °C followed by a 10-fold dilution in LB broth with 1 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 3 h. After the incubation, the EGFP-expressing J96 was washed and resuspended with the PBS.

Immunohistochemistry

Human tissue specimens were obtained from Sapporo Medical University Hospital in agreement with the bioethics at the hospital. These human specimens obtained from a macroscopically normal area (safety margin) distant from the region of carcinoma were used for immunohistochemistry. To produce polyclonal antibody against human SP-D, purified recombinant human SP-D was emulsified with Freund's complete adjuvant and injected into New Zealand White rabbits intramuscularly (25, 26). After boost immunization, serum was harvested. The IgG fraction of antiserum against human SP-D was purified by an affinity column on protein A-Sepharose CL-4B (GE healthcare) as described previously for the preparation of anti-mannose-binding protein polyclonal antibody (27). The anti-SP-D polyclonal antibody reacted with SP-D in human alveolar lavage fluids (data not shown) or recombinant human SP-D (25) but not with recombinant human SP-A (25) or SP-A in human alveolar lavage fluids (data not shown) by Western blotting. Human lung, bladder, and prostate tissues were fixed by 3% (w/v) formaldehyde and paraffin-embedded. After deparaffinization, antigen retrieval was carried out at 105 °C for 10 min by an autoclave treatment in antigen retrieval solution (pH 9) (Nichirei Biosciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan). After antigen retrieval, those sections were stained with an anti-human SP-D polyclonal antibody (100 μg/ml), universal negative control rabbit (100 μg/ml) (Dako), or anti-human uroplakin Ia polyclonal antibody (1:200) (Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

SP-D Expression in Human Urine

Normal human urine from healthy volunteers was used for immunoblot analysis to detect the SP-D protein in urine. Human urine was concentrated 15-fold by centrifugation using AmiconUltra 30 kDa (Merck Millipore). Native human SP-D derived from bronchoalveolar lavage fluids of patients with alveolar proteinosis was purified by affinity chromatography on mannose-Sepharose as described previously (26). The concentrated urine, native SP-D (10 ng), and recombinant SP-D (10 ng) were boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer under reducing conditions. Samples were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore Corp.). The membrane was then incubated with anti-human SP-D polyclonal antibody followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled anti-rabbit antibody. Anti-human β-defensin 4 (FL-72) polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was used as a control antibody.

Binding of SP-D to UPEC

The suspension of UV-killed bacteria (107 cfu in 50 μl of ethanol/well) was put into microtiter wells (Immulon 1B; Thermo) and dried. After washing the wells three times with PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 (washing buffer), nonspecific binding was blocked with 5 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.15 m NaCl and 2% (w/v) fatty acid-free BSA. The wells were then incubated with the indicated concentrations of SP-D in 5 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.15 m NaCl, 2 mm CaCl2, and 2% (w/v) fatty acid-free BSA (buffer A) at 37 °C for 2 h. The wells were washed three times with the washing buffer followed by incubation with anti-SP-D polyclonal antibody (5 μg/ml) in the binding buffer at 37 °C for 1 h. After washing three times with the washing buffer, HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was added and further incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Finally, a peroxidase reaction was performed using o-phenylenediamine as a substrate. The binding of SP-D to J96 was detected by measuring absorbance at 492 nm. In some experiments, 2 mm EDTA or 0.2 m α-methyl-d-mannoside was included in buffer A instead of CaCl2.

The binding study was also performed in the solution phase. J96 (109 cfu) was incubated with SP-D (50 μg/ml) in 50 μl of 5 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.15 m NaCl, 5% (w/v) BSA, and 2 mm CaCl2 (buffer B) at 37 °C for 1 h. After the incubation, the mixture of J96 and the protein was washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 by centrifugation. The bacterial pellet obtained by the final centrifugation was suspended with 40 μl of PBS and 10 μl of SDS sample buffer. The suspension of the pellet was boiled for 5 min and centrifuged. The 15-μl supernatant obtained was subjected to SDS-PAGE. Blotting analysis was next performed to detect SP-D cosedimented with the bacteria. Proteins on the gels were transferred onto PVDF membrane. The membrane was immunoprobed with anti-human SP-D polyclonal antibody (3 μg/ml) followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG. The protein bands were visualized by using a chemiluminescence reagent (SuperSignal, Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In some experiments, 5 mm EDTA or 0.2 m α-methyl-d-mannoside was included in buffer B instead of CaCl2.

Agglutination of UPEC by SP-D

J96 (5 × 108 cfu) was mixed with or without SP-D (20 μg/ml) in a cuvette containing 500 μl of 20 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.15 m NaCl and either 5 mm CaCl2 or 5 mm EDTA, and the cuvette was left at rest for the indicated length of time. At each time point (every 1 h), bacterial agglutination was determined by measuring the absorbance at 660 nm. In some experiments, EGFP-expressing J96 was incubated with or without SP-D (20 μg/ml) in the presence of 5 mm CaCl2 for 2 h. After the incubation, the bacteria were observed by fluorescence microscopy.

Adherence of UPEC to the Urothelial Cells

Human urothelial bladder cell line 5637 was maintained in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. Cells (105 cells/well) were seeded into a 24-well plate and allowed to adhere overnight. After being washed with the medium, the cells were incubated with or without SP-D (10 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 1 h. After the incubation, the cells were washed and incubated with EGFP-expressing J96 (106 cfu/well) at 37 °C for 1 h. Non-adherent J96 cells were then removed by washing the cells with PBS, and the 5637 cells were stained with 0.5% (w/v) rhodamine-conjugated concanavalin A (Vector Laboratories) at 37 °C for 15 min to detect cell surfaces. After the cells were washed with PBS, the cells were observed by fluorescence microscopy, and the numbers of J96 adherent cells were counted. In some experiments, EGFP-expressing J96 (106 cfu/well) was preincubated with or without SP-D (10 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 1 h. After the incubation, the mixture was washed with culture medium, and the complex of J96 and SP-D was isolated by centrifugation at 1,700 × g for 3 min and then further incubated with 5637 cells at 37 °C for 1 h.

Cell Membrane Permeability

The 5637 cells were incubated with SP-D (10 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 1 h. The cells were washed and infected with J96 (106 cfu/well) at 37 °C for 1 h. After the incubation, non-adherent J96 was washed with PBS, and the 5637 cells were stained with 25 μg/ml ethidium bromide and 5 μg/ml acridine orange to examine the permeability of cell membranes (23). All cells were stained with acridine orange, whereas only the cells with damaged membrane were stained with ethidium bromide. The cells were observed under fluorescence microscopy, and cytotoxic activity was determined as the percentage of the cells stained with ethidium bromide in total cells counted.

Purification of FimH Receptor-binding Domain

The expression and purification of the FimH receptor-binding domain (FimH-RBD), corresponding to the N-terminal half of the FimH region of Met1–Gly181 (encoding the signal peptide and the first 156 amino acids of mature protein), were performed as reported previously (28). The His-tagged FimH-RBD that contained a C-terminal fusion of the His tag was subcloned into the QE-30 vector (Qiagen). BL21 cells (GE Healthcare) transformed with the plasmid described above were grown until the A600 reached 0.6, and FimH-RBD production was induced with 1 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 1 h. Periplasmic protein fractions were prepared as described previously (28). The FimH-RBD was purified from this periplasmic fraction by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Biotinylation of Cell Surface Protein, Immunoprecipitation, and Immunoblotting

The cDNAs for human UPIa and UPII were generated by RT-PCR from human urothelial bladder cancer cell line RT4. FLAG-tagged UPIa that contained the C-terminal fusion 3XFLAG tag was subcloned into the p3XFLAG-CMVTM-14 expression vector (Sigma-Aldrich). V5-tagged UPII that contained the C-terminal fusion V5 tag was generated by PCR and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen). Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged UPIa (12 μg) with or without V5-tagged UPII (12 μg) by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The total amount of transfected DNA was kept constant with an empty vector. Forty hours after transfection, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS (+) containing 0.1 mm CaCl2 and 1 mm MgCl2, and cell surface proteins were labeled with EZ-Link sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (0.5 mg/ml) (Pierce) in ice-cold PBS (+) at 4 °C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by washing and incubating the cells in PBS (+) containing 100 mm glycine for 10 min at 4 °C. The cells were lysed in a lysis buffer (20 mm Hepes buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.1 m NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 20 mm EGTA, 50 mm NaF, and 2 mm Na3VO4) on ice for 15 min. The cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation and precipitated using streptavidin-agarose (Invitrogen), anti-FLAG antibody-conjugated agarose (Sigma), or monoclonal anti-V5 antibody-conjugated agarose (Medical & Biological Laboratories Corp., Nagoya, Japan). Immunoprecipitates were washed and released after being boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer under reducing conditions. Samples were resolved by 7.5–15% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore Corp.). The membrane was then incubated with anti-FLAG polyclonal antibody or anti-V5 polyclonal antibody followed by incubation with HRP-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibody. For lectin blot analysis, the membranes were blocked with 5% BSA and then incubated with biotin-conjugated concanavalin A (J-Oil Mills, Tokyo, Japan). The lectin-reactive proteins were detected by HRP-labeled streptavidin and visualized using a chemiluminescence reagent as described above.

Binding of SP-D and FimH to UPIa

The p3XFLAG-CMV-7-BAP control plasmid (Sigma-Aldrich), which expresses an N-terminal 3XFLAG-bacterial alkaline phosphatase (BAP) fusion protein in mammalian cells, was used as a control. The 293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged UPIa (12 μg) and V5-tagged UPII (12 μg) or with FLAG-tagged BAP (12 μg) and a pcDNA3.1 vector (12 μg) by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Forty hours after transfection, the cells were lysed in a lysis buffer as described above.

For the binding study, microtiter wells (Immulon 1B, Dynex) were coated with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (100 ng/well). After the wells were blocked with 20 mm Hepes buffer (pH 7.4) containing 3% (w/v) lipid-free BSA, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.1 m NaCl, and 2 mm CaCl2 (blocking buffer), the cell lysates were added, and the suspension was incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The wells were then washed with PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 and incubated with SP-D (1 μg), FimH-RBD (1 μg), or BSA (1 μg) in the blocking buffer. The binding of SP-D or FimH-RBD to UPIa was detected by anti-SP-D polyclonal antibody or anti-His polyclonal antibody followed by an incubated with HRP-labeled anti-rabbit IgG. A peroxidase reaction was carried out by using o-phenylenediamine as a substrate, and the absorbance at 492 nm was measured.

Competition of SP-D with FimH-RBD for UPIa Binding

The 293T cells were co-transfected with FLAG-tagged UPIa (12 μg) and V5-tagged UPII (12 μg) or with p3XFLAG-CMV-14 expression vector (12 μg) and pcDNA3.1 vector (12 μg) by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Forty hours after transfection, the cells were lysed in a lysis buffer as described above. Microtiter wells (Immulon 1B, Dynex) were coated with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (200 ng/well), and the wells were then blocked with PBS containing 10% FCS. The cell lysates were added onto the wells and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The wells were then washed with PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 and incubated with SP-D (1 μg), or BSA (1 μg) in 10 mm Hepes buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.15 m NaCl and 2 mm CaCl2 for 2 h at 37 °C. After the incubation, the wells were washed with PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 and were further incubated with His-tagged FimH-RBD (100 ng) for 2 h at 37 °C. The binding of FimH-RBD to UPIa was detected by using anti-His polyclonal antibody followed by incubation with HRP-labeled anti-rabbit IgG as described above.

Murine Model of UTI

Animal care and experiments were conducted according to the regulations of the Sapporo Medical University Animal Care and Use Committee. Female C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks) were purchased from Sankyo Labo Service Corp. Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. After mice were anesthetized and sterilized in the periurethral area with 70% ethanol, 50 μl of inoculum containing 108 cfu of J96 and 2 mm CaCl2 in saline was instilled transurethrally into the bladder using a 1-ml syringe attached to a sterile 24-gauge catheter (outer diameter, 0.7 mm; length, 19 mm; Terumo Corp., Japan). The external urethral orifices of mice were clamped for 2 h.

For the detection of SP-D mRNA, mice were euthanized at 24 h after challenge. Three mice were used in each group. Bladders were then excised aseptically and washed with saline containing 2 mm CaCl2 (buffer A). Murine bladders and lungs from non-infected mice were preserved in RNAlater RNA Stabilization Reagent (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) for a few days at −80 °C for detection of SP-D mRNA by RT-PCR. The experiment was independently repeated three times.

To analyze the effect of exogenous administration of SP-D in the UTI murine model, 5 × 107 cfu of J96 with or without SP-D (50 μg/ml) was injected into the bladders, and the external urethral orifices were clamped for 2 h. After euthanasia, the bladders were excised, washed, and homogenized in buffer A. The bladder homogenates were serially diluted in PBS and plated onto LB agar for colony counts. The colony number was counted 16 h after plating. To assess UPEC-induced histological changes of the bladder, mice were euthanized at 48 h after administration of UPEC with or without SP-D. The bladders were fixed with 15% buffered formalin phosphate and embedded in paraffin. Bladder sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and examined under light microscopy. In the examinations with the UTI murine model, three independent experiments with three mice in each group were performed.

RT-PCR and Sequence Analysis

Total RNAs from mouse lung and bladder tissues were extracted using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR for SP-D was performed using forward primer 5′-ACTCATCACAGCCCACAACA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TCAGAACTCACAGATAACAAG-3′, corresponding to 903–1125 of mouse SP-D cDNA. PCR for GAPDH was performed using forward primer 5′-CTCATGACCACAGTCCATGC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CACATTGGGGGTAGGAACAC-3′, corresponding to 564–764 of mouse GAPDH cDNA. The expected size of the PCR products for SP-D and GAPDH were 223 and 201 bp, respectively. The UV-illuminated gels were photographed, and densitometric analysis was performed using a LumiVision analyzer (Aishin Seiki Co., Japan). The experiment was independently repeated three times.

The amplified PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel. In some experiments, the amplified PCR products were purified using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). DNA sequencing was carried out using a BigDye terminator V3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI PRISM 3130 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

RESULTS

SP-D and Uroplakin Ia Are Co-expressed in the Bladder

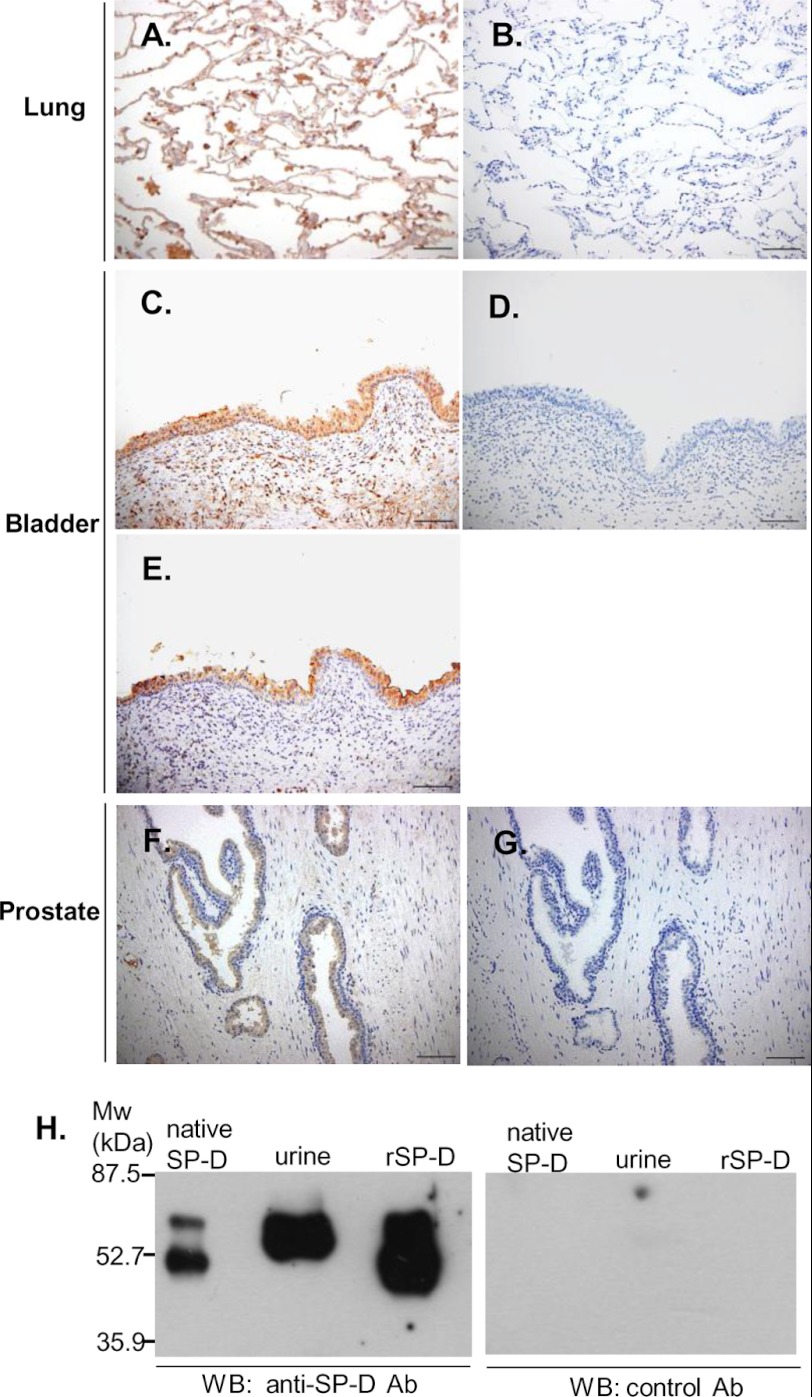

We first determined whether SP-D was expressed in the bladder. The human kidney, prostate, bladder, and lung were examined by immunostaining. Anti-SP-D polyclonal antibody (Fig. 1A) but not control antibody (Fig. 1B) stained SP-D expressed in alveolar type II cells of the lung, indicating the specificity of the anti-SP-D antibody used. SP-D was detected in mucosal epithelium of the bladder (Fig. 1C). In addition, the prostate gland epithelium (Fig. 1F) and distal renal tubular cells (data not shown) were also immunostained with anti-SP-D antibody but not control antibody (Fig. 1, B, D, and G). UPIa was also detected in the mucosal epithelium of the bladder (Fig. 1E). These data indicate that both SP-D and UPIa are expressed in the mucosal epithelium of the bladder.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of human SP-D. A–G, immunostaining of SP-D and uroplakin Ia in human tissue. Human lung (A and B), bladder (C–E), and prostate (F and G) were fixed by 3% formaldehyde and paraffin-embedded. The sections were stained with an anti-human SP-D polyclonal antibody (A, C, and F), control antibody (B, D, and G), or anti-uroplakin Ia polyclonal antibody (E) and observed under light microscopy. Representative specimens are shown from two independent experiments. Scale bars, 100 μm. H, detection of SP-D in human urine. The concentrated urine, native SP-D, and recombinant SP-D (rSP-D) were boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer under reducing conditions. SP-D expression in urine was analyzed by immunoblot using an anti-SP-D polyclonal (Ab) antibody as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Representative results are shown from three independent experiments. WB, Western blot.

SP-D Is Present in Human Urine

SP-D protein is detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in urine (29). We determined whether SP-D was present in human urine by Western blot analysis using anti-SP-D polyclonal antibody. As shown in Fig. 1H, anti-SP-D antibody but not control antibody detected the SP-D protein in urine. The molecular mass of the urine SP-D appeared to be slightly larger than those of native SP-D and recombinant SP-D. This is probably due to the differences of the post-translational glycosylation among individuals as reported previously (30). These results are consistent with the idea that SP-D was expressed in the bladder.

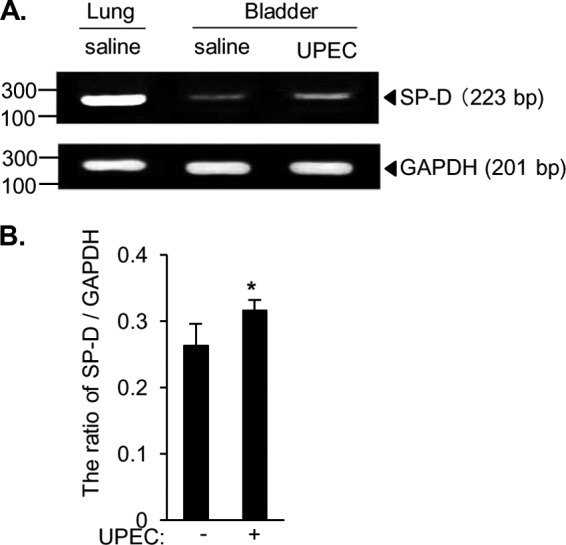

Increased Expression of SP-D mRNA in the Bladder of the UPEC Infection Model in Mice

A previous study has shown that SP-D mRNA and protein are present in the epithelial cells of female reproductive tissues in mice and that mice infected with Chlamydia contain increased amounts of SP-D in the reproductive tract (31). In addition, a rat prostatitis model achieved by direct infection with E. coli increased SP-D expression in the prostate (32). Thus, we examined the effect of UPEC infection on SP-D mRNA expression in the murine bladder. Twenty-four hours after transurethral administration of UPEC or saline, the expression of SP-D mRNA was examined. The 223-bp PCR fragment of mouse SP-D and the 201-bp PCR fragment of mouse GAPDH were excised from the gel and sequenced. The sequence of SP-D or GAPDH obtained from mouse bladder was respectively identical to that obtained from mouse lung. Although SP-D mRNA was less expressed in the bladder than in the lung of uninfected controls, the level of SP-D mRNA was clearly increased in the bladder of mice infected with UPEC when compared with the uninfected bladder (Fig. 2A). The ratio of the SP-D/GAPDH band intensities significantly increased for mice infected with UPEC when compared with the ratio for uninfected bladder (Fig. 2B). The results indicate that the SP-D expression in the bladder is increased in response to UPEC infection, suggesting that SP-D plays important roles against the urinary tract infection as an acute phase reactant.

FIGURE 2.

Increased expression of SP-D mRNA in the bladder of the UPEC infection model in mice. A, J96 (108 cfu) or saline was injected into the bladder of female C57BL/6 mice, and the external urethral orifices were clamped for 2 h. Twenty-four hours after infection, the bladders from infected and non-infected mice and the lungs from non-infected mice were excised and used for detection of SP-D mRNA by RT-PCR as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Representative results are shown. B, densitometric analysis of the PCR bands shown as the ratio of SP-D/GAPDH. The data shown are the means ± S.D. (error bars) from three separate experiments. *, p < 0.05 when compared with uninfected bladder.

Direct Interaction of SP-D with UPEC Decreases the Bacterial Adherence to the Urothelial Bladder Cells and the Bacterial Cytotoxicity

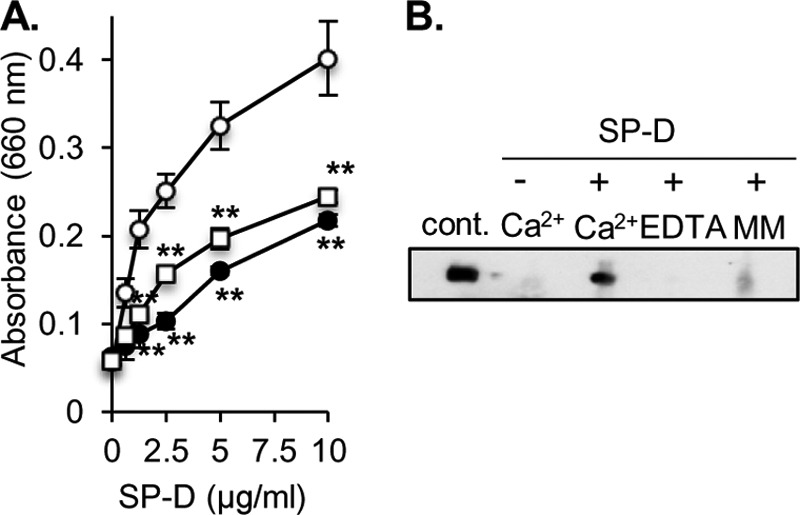

We examined the binding of recombinant SP-D to UPEC strain J96 coated onto microtiter wells. SP-D exhibited a concentration-dependent binding to J96 in the presence of 2 mm CaCl2 (Fig. 3A). Because SP-D belongs to the C-type lectin family, it recognizes ligands via the carbohydrate recognition domain in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Thus, we next examined the binding of SP-D to UPEC in the presence of EDTA or excess α-methyl-d-mannoside (Fig. 3A). The binding was inhibited in the buffer containing 2 mm EDTA or α-methyl-d-mannoside instead of CaCl2 (Fig. 3A). The interaction of SP-D with UPEC was also examined in solution phase. J96 was incubated with or without SP-D in the presence of 2 mm CaCl2, 5 mm EDTA, or 0.2 m α-methyl-d-mannoside, and SP-D co-sedimented with the bacteria was detected. SP-D was co-sedimented with J96 in the presence of Ca2+ (Fig. 3B) but not in the presence of EDTA, indicating that SP-D binds to J96 in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Moreover, the association of SP-D with J96 was attenuated by the presence of 0.2 m α-methyl-d-mannoside, indicating the possibility that the carbohydrate recognition domain is involved in the interactions of SP-D with UPEC. These results clearly indicate that SP-D binds UPEC.

FIGURE 3.

Recombinant human SP-D binds to UPEC. A, the indicated concentrations of SP-D were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h with UV-killed J96 coated onto microtiter wells (107 cfu/well) in the presence of 2 mm CaCl2 (open circles), 2 mm EDTA (closed circles), or 0.2 m α-methyl-d-mannoside (open squares). The SP-D binding to the solid phase UPEC was detected using an anti-human SP-D polyclonal antibody as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data shown are the means ± S.D. (error bars) from three to six separate experiments. **, p < 0.01 when compared with 2 mm CaCl2. B, J96 (109 cfu) was incubated with or without 2 μg of SP-D in the presence of 2 mm CaCl2, 5 mm EDTA, or 0.2 m α-methyl-d-mannoside (MM) at 37 °C for 1 h. After the incubation, the mixture of J96 and protein was washed and centrifuged. The bacterial pellet obtained was subjected to SDS-PAGE, and blotting analysis was performed to detect SP-D co-sedimented with the bacteria as described under “Experimental Procedures.” As a positive control, recombinant SP-D (20 ng) was loaded. Representative results are shown from three independent experiments. cont., control.

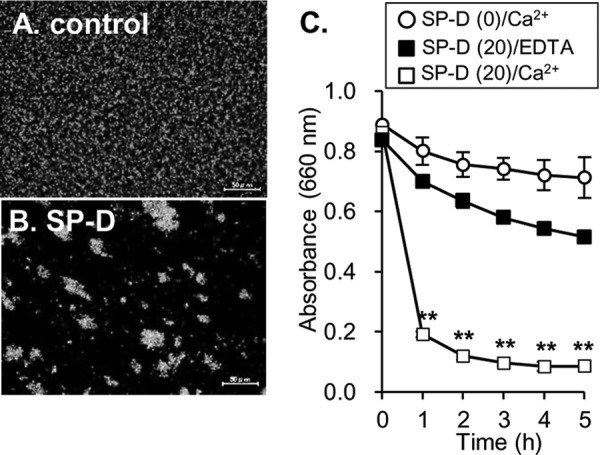

Because SP-D was shown to agglutinate E. coli (18, 19), we next examined whether SP-D agglutinated and precipitated J96. EGFP-expressing J96 was incubated with or without SP-D and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Fig. 4, A and B). SP-D strongly agglutinated J96 in the presence of Ca2+ (Fig. 4B). J96 and SP-D were co-incubated in the cuvette, which was then left at rest, and the turbidity was measured at 660 nm. Co-incubation of the bacteria with 20 μg/ml SP-D decreased the turbidity (Fig. 4C). This indicates that SP-D can agglutinate and precipitate UPEC, resulting in the increased transparency in the cuvette. When 20 μg/ml SP-D was co-incubated in the presence of EDTA, decreased turbidity was not observed (Fig. 4C), indicating that agglutination of the bacteria by SP-D is Ca2+-dependent. Taken together, these results show that SP-D agglutinates and precipitates UPEC.

FIGURE 4.

SP-D agglutinates UPEC in a Ca2+-dependent manner. A and B, EGFP-expressing J96 (109 cfu) was incubated with or without SP-D (20 μg/ml) in the presence of 5 mm CaCl2. After the incubation, the bacteria were observed by fluorescence microscopy (original magnification, ×400). Scale bars, 50 μm. C, J96 (5 × 108 cfu) was mixed with or without SP-D (20 μg/ml) in a cuvette containing 5 mm CaCl2 or 5 mm EDTA, and the cuvette was left at rest for the indicated length of time. At each time point, bacterial precipitation was determined by measuring the absorbance at 660 nm. The data shown are the means ± S.D. (error bars) from three separate experiments. **, p < 0.01 when compared with the absorbance at time 0.

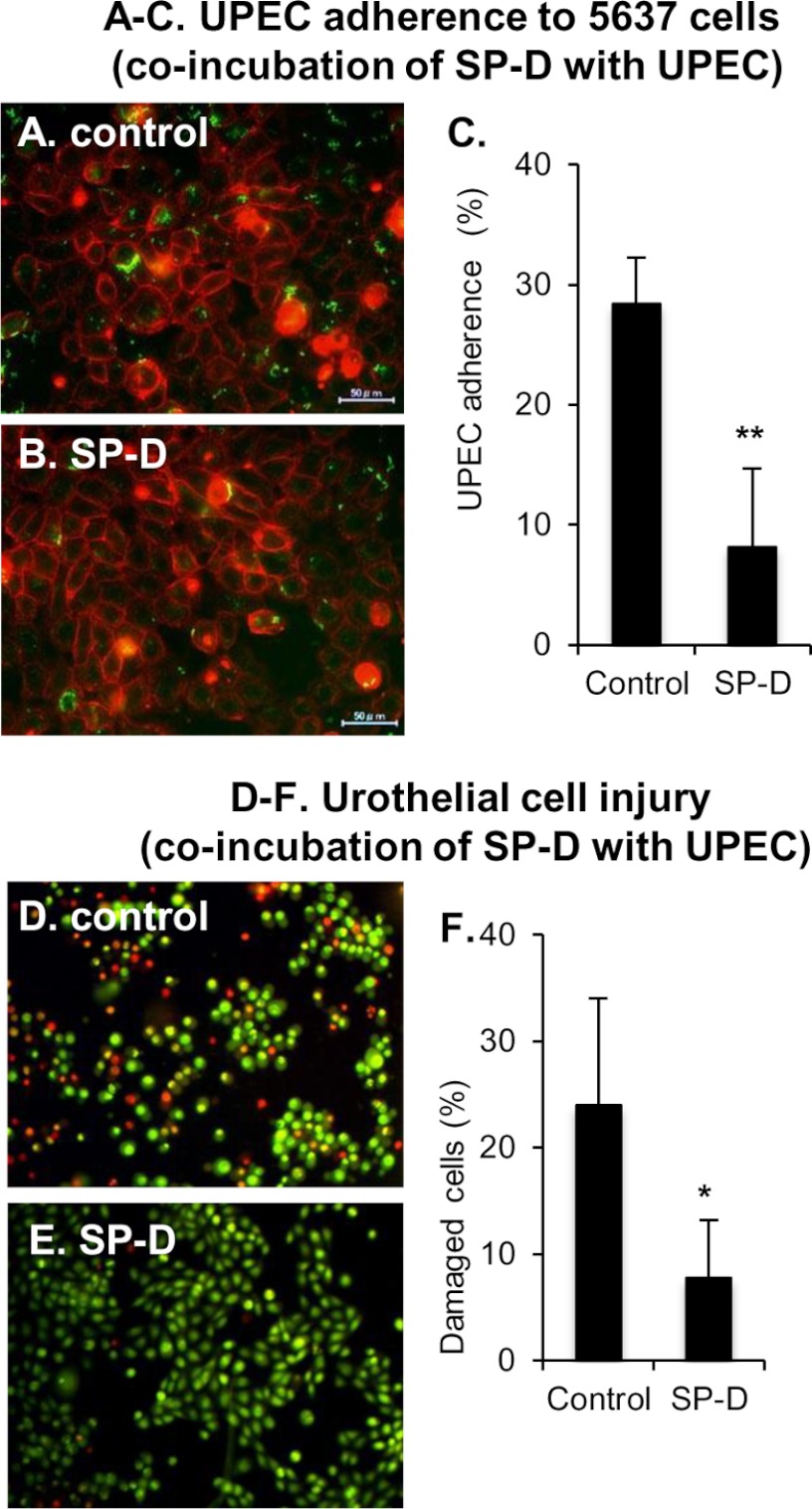

The binding of UPEC to urothelium is the first step of UPEC infection. The results described above prompted us to examine whether SP-D affected adherence of UPEC to the urothelial bladder cell line 5637 when SP-D and the bacteria exist as a complex. The EGFP-expressing J96 was incubated with or without SP-D at 37 °C for 1 h. After the incubation, the J96 and SP-D complex was isolated by centrifugation and then further incubated with 5637 cells at 37 °C for 1 h. J96-adherent cells were observed (Fig. 5, A and B) and counted (Fig. 5C) by fluorescence microscopy. A significant number of J96 isolated without SP-D adhered to the 5637 cells (Fig. 5A). In contrast, J96 that was isolated after the incubation with SP-D exhibited much less adherence to the cell (Fig. 5, B and C). We next examined the UPEC-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 5, D–F). The cells with permeabilized membranes were stained in red, whereas the cells with intact membrane were stained in green. Consistent with the results obtained from adherence experiments (Fig. 5, A–C), the incubation of J96·SP-D complex significantly decreased the number of the damaged cells (Fig. 5, D–F). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the direct interaction of SP-D with UPEC significantly attenuates the bacterial adherence to the urothelial cells and results in the reduction of UPEC-induced cytotoxicity in vitro. This suggests that SP-D plays a protective role against UPEC infection by its direct action on the microbes.

FIGURE 5.

Co-incubation of UPEC and SP-D inhibits the bacterial adherence to urothelial cells and its cytotoxicity. EGFP-expressing J96 (106 cfu/well) was incubated with or without SP-D (10 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 1 h. After the incubation, the complex of J96 and SP-D was isolated and further incubated with 5637 cells. A–C, UPEC adherence. The 5637 cells were stained with 0.5% (w/v) concanavalin A and observed by fluorescence microscopy (A and B). Scale bars, 50 μm. The percentage of J96-adherent cells is shown (C). The data shown are the means ± S.D. (error bars) from three separate experiments. **, p < 0.01 when compared with control. D–F, urothelial cell injury. The 5637 cells were stained with 25 μg/ml ethidium bromide and 5 μg/ml acridine orange to examine the permeability of cell membranes (D and E). The percentage of cells stained with ethidium bromide in total cells counted is shown (F). The data shown are the means ± S.D. (error bars) from three separate experiments. *, p < 0.05 when compared with the control.

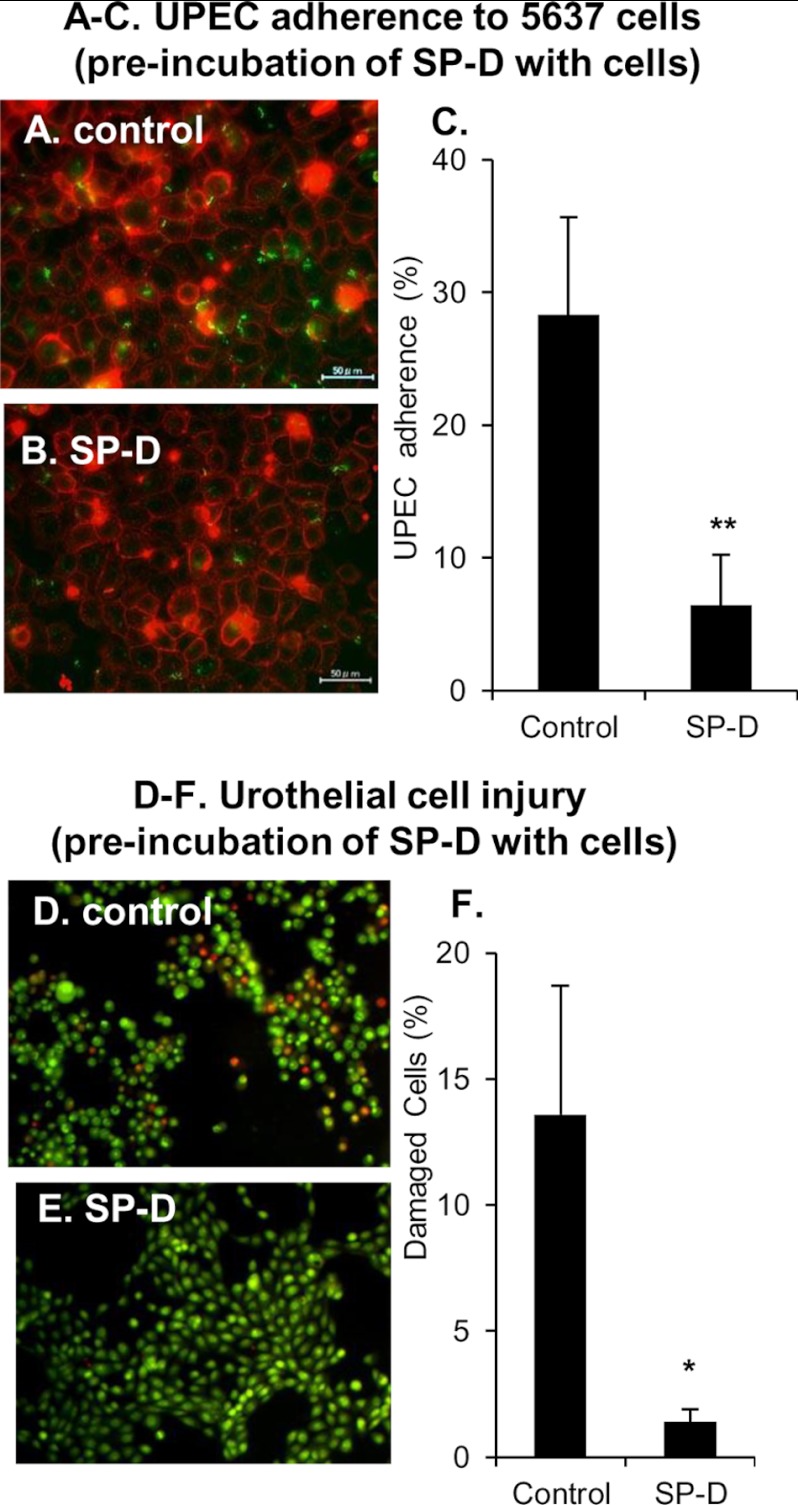

SP-D Protects the Urothelial Bladder Cells against UPEC by Competing with FimH for the Binding to Uroplakin Ia

Because SP-D binds to cell surface receptors and modulates inflammatory cellular responses (10–12, 25, 33), we next examined whether direct interaction between SP-D and the bladder epithelial cells protected urothelium against UPEC. The 5637 cells were preincubated with or without SP-D (10 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 1 h. After the incubation, the cells were washed and infected with EGFP-expressing J96 (106 cfu/well) at 37 °C for 1 h. The 5637 cells were finally observed by fluorescence microscopy. The numbers of J96-adherent cells were clearly decreased in SP-D-treated cells when compared with the control (Fig. 6, A and B). Preincubation of the 5637 cells with SP-D reduced the numbers of UPEC-adherent cells by ∼78% when compared with the control (Fig. 6C). Similarly, preincubation with SP-D and washing the cells clearly decreased the numbers of ethidium bromide-staining cells when compared with the control (Fig. 6, D and E). The percentage of damaged cells in SP-D-treated cells was approximately one-tenth of that in control (Fig. 6F). These results indicate that the direct actions of SP-D not only on UPEC but also on the cells inhibit UPEC adherence and urothelial cell injury.

FIGURE 6.

Preincubation of urothelial cells with SP-D inhibits UPEC adherence and cell injury. The 5637 cells were incubated with or without SP-D (10 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 1 h. After the incubation, the cells were washed to remove non-adherent SP-D and infected with EGFP-expressing J96 (106 cfu/well) at 37 °C for 1 h. A–C, UPEC adherence. The 5637 cells were stained with 0.5% (w/v) concanavalin A and observed by fluorescence microscopy (A and B). Scale bars, 50 μm. The percentage of J96-adherent cells is shown (C). The data shown are the means ± S.D. (error bars) from three separate experiments. **, p < 0.01 when compared with the control. D–F, urothelial cell injury. The 5637 cells were stained with 25 μg/ml ethidium bromide and 5 μg/ml acridine orange to examine the permeability of cell membranes (D and E). The percentage of cells stained with ethidium bromide in total cells counted is shown (F). The data shown are the means ± S.D. (error bars) from three separate experiments. *, p < 0.02 when compared with control.

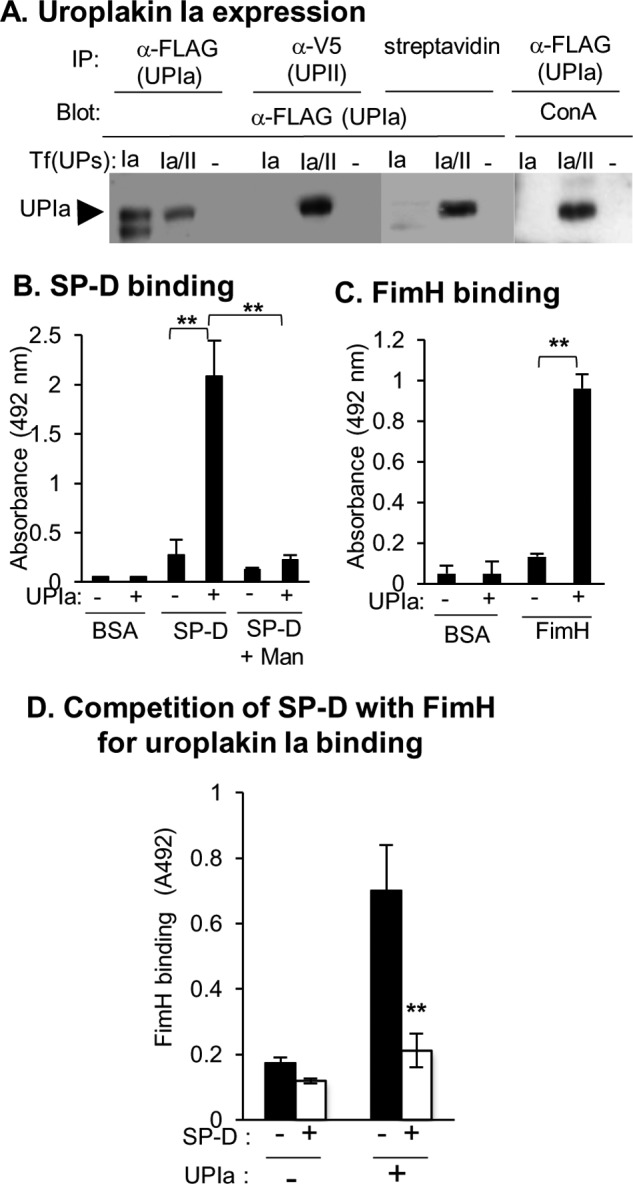

We attempted to clarify the mechanisms by which the interaction of SP-D with the cells protected urothelium against UPEC. UPIa contains high mannose glycans that are capable of interaction with FimH (7). Because SP-D as well as FimH prefers to bind mannosyl ligands, we examined whether SP-D directly bound to UPIa. First, we tested the expression of UPIa with high mannose glycans. The 293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged UPIa with or without V5-tagged UPII. The cell surface proteins were labeled with biotin. Although UPIa was expressed regardless of the presence or absence of UPII (Fig. 7A, IP: α-FLAG/Blot: α-FLAG), UPIa possessed high mannose glycans (Fig. 7A, IP:α-FLAG/Blot: ConA) and was expressed on the cell surface (Fig. 7A, IP: streptavidin/Blot: α-FLAG) only when UPII was co-transfected. Thus, UPIa was co-transfected with UPII in the following experiments.

FIGURE 7.

SP-D and FimH bind to UPIa. A, the 293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged uroplakin Ia with or without V5-tagged uroplakin II (Tf(UPs): Ia/II or Ia) or with the p3XFLAG-CMV-14 expression vector and pcDNA3.1 vector (Tf(UPs): −). The cell surface proteins were biotinylated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using an anti-FLAG antibody or anti-V5 antibody or pulled down using streptavidin-agarose. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot (Blot) using an anti-FLAG antibody, anti-V5 antibody, or concanavalin A (ConA). B and C, the 293T cells were co-transfected with FLAG-tagged uroplakin Ia and V5-tagged uroplakin II (UPIa: +) or with FLAG-tagged BAP and the pcDNA3.1 vector (UPIa: −). Forty hours after transfection, the cells were lysed, and the cell lysate was incubated with the anti-FLAG antibody coated onto microtiter wells. The binding of SP-D (B) and receptor-binding domain of FimH (C) to uroplakin Ia captured by the anti-FLAG antibody was analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” In some experiments, 0.2 m α-methyl-d-mannoside (Man) was added instead of CaCl2. The data shown are means ± S.D. (error bars) from three to six separate experiments. **, p < 0.01 when compared with the indicated samples. D, SP-D competes with FimH for the binding to uroplakin Ia. The 293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged uroplakin Ia and V5-tagged uroplakin II (UPIa: +) or with a p3XFLAG-CMV-14 expression vector (UPIa: −). Forty hours after transfection, the cell lysates were incubated with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody coated onto microtiter wells. After the incubation, SP-D (1 μg; open squares) or BSA (1 μg; closed squares) was added to the wells and incubated for 1 h. After the wells were washed, the His-tagged FimH-RBD (100 ng) was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The binding of FimH-RBD to uroplakin Ia was detected using the anti-His polyclonal antibody followed by incubation with HRP-labeled anti-rabbit IgG as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data shown are the means ± S.D. (error bars) from four separate experiments. **, p < 0.01 when compared with the experiments with UPIa (+) and SP-D (−).

We next examined whether SP-D directly bound to UPIa captured by anti-FLAG antibody coated onto microtiter wells. As shown in Fig. 7B, SP-D but not BSA directly bound to UPIa. The interaction was inhibited by 0.2 m mannose (Fig. 7B). In addition, we analyzed FimH binding to UPIa captured by the anti-FLAG antibody. We confirmed that FimH-RBD but not BSA directly bound to UPIa (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that both SP-D and FimH directly bind to UPIa.

We next examined whether SP-D affected the FimH binding to UPIa. After preincubation of SP-D or BSA with UPIa captured by anti-FLAG antibody coated onto microtiter wells, the wells were further incubated with His-tagged FimH-RBD. The binding of FimH-RBD to the UPIa was ultimately detected by the anti-His antibody. Preincubation of SP-D with UPIa significantly decreased the binding of FimH-RBD to UPIa (Fig. 7D). SP-D reduced the FimH binding to UPIa by ∼70% when compared with BSA. The binding of FimH-RBD to the cell lysate from the cells transfected with the p3XFLAG empty vector was weak and exhibited no difference between the preincubations with or without SP-D. The results clearly indicate that SP-D competes with FimH for UPIa binding.

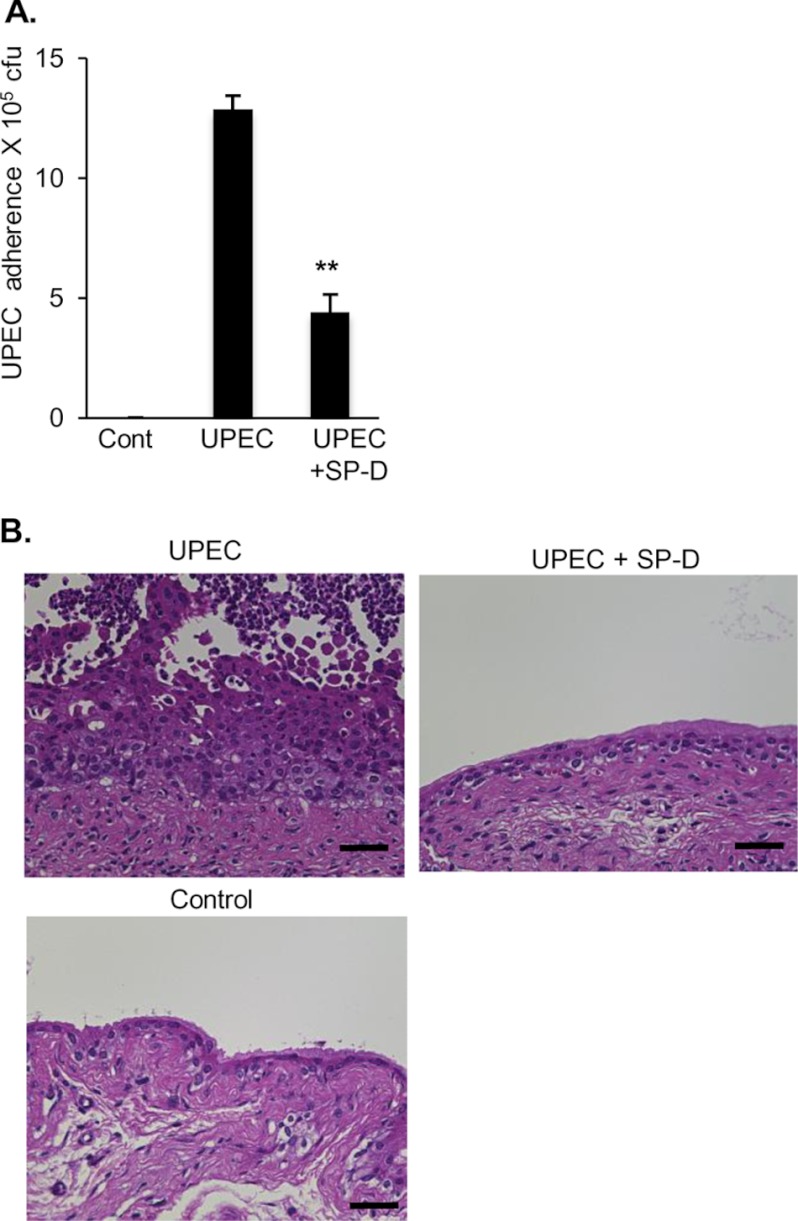

Exogenous Administration of SP-D Attenuates UPEC Adherence to the Bladder and Dampens UPEC-induced Inflammation in Mice

In addition to the in vitro experiments, we examined the protective roles of SP-D against UPEC in vivo. The murine bladders were infected transurethrally with UPEC in the presence or absence of SP-D. Two hours after the infection, the bladders were excised, washed to remove non-adherent UPEC, and homogenized. The homogenates were spread onto an LB agar plate, and the colony number on the plate was counted. Mice that were given SP-D in addition to UPEC exhibited markedly decreased UPEC adherence to the bladder (Fig. 8A).

FIGURE 8.

Exogenous administration of SP-D attenuates UPEC adherence to the bladder and dampens UPEC-induced inflammation in mice. An inoculum containing 5 × 107 cfu of J96 with or without SP-D (50 μg/ml) was injected transurethrally into the bladders of female C57BL/6 mice, and the external urethral orifices were clamped for 2 h. Three independent experiments with three mice in each group were performed. A, UPEC adherence. After euthanasia, the bladders were excised, washed to remove non-adherent UPEC, and then homogenized. The bladder homogenates were serially diluted in PBS and plated onto LB agar for colony counts. The data are the means ± S.D. (error bars) of three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01 when compared with the absence of SP-D. B, UPEC-induced histological changes of the bladder. Mice were euthanized at 48 h after administration of UPEC with or without SP-D as described above. The bladders were fixed with 15% buffered formalin phosphate and embedded in paraffin. Bladder sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and observed under light microscopy. Scale bars, 40 μm. Representative results are shown from three independent experiments. Cont, control.

We next determined whether co-administration of SP-D with UPEC protected the bladder against UPEC-induced inflammation. Transurethral injection of UPEC induced abrasion of umbrella cells and exudates including neutrophils in the lumen and resulted in increased basal layer and reactive atypical epithelium (Fig. 8B), whereas saline-treated murine bladders did not show any findings indicative of inflammation. When SP-D was co-administered with UPEC, the histological findings indicative of UPEC-induced inflammation were not observed (Fig. 8B).

Taken together, the results indicate that transurethral administration of SP-D not only inhibits UPEC adherence to the bladder but also dampens the UPEC-induced inflammation in vivo. These data suggest a possible important role of SP-D against UPEC infection.

DISCUSSION

SP-D plays important roles in innate immunity of the lung (10–12). In this study, anti-SP-D antibody prepared against recombinant SP-D stained non-pulmonary tissues including the bladder, prostate, and kidney. Other previous studies (20–22) also indicated that various mucosal tissues besides the lung express SP-D. However, the roles of SP-D in non-pulmonary tissues are poorly understood. Both the present study (see Fig. 1) and another study (20) show that SP-D is expressed in the bladder urothelium. This study (see Fig. 1H) and a previous study (29) indicate the presence of SP-D protein in human urine. The results from immunochemistry and immunoblot analysis are consistent with the idea that SP-D is expressed in the bladder.

The SP-D expression in the bladder of mice is increased in response to UPEC infection (see Fig. 2). Previous studies have shown that SP-D expression is increased in the mouse reproductive tract (31) and rat prostate (32) infected with Chlamydia and E. coli, respectively. A recent report showed that the urine SP-D levels were decreased in patients with recurrent urinary tract infection compared with healthy individuals (29). Taken together with the results obtained from this study and previous studies (29, 31, 32), the endogenous lectin SP-D possesses potential functions to protect against the bacterial infection. We investigated the protective role of SP-D in adherence of UPEC to the bladder urothelium, which is the first critical step for establishing UPEC infection, and examined the mechanisms of SP-D-dependent defense against UPEC infection.

In this study, we show that SP-D directly binds to UPEC and agglutinates the bacteria (see Figs. 3 and 4). SP-D has been shown to bind with broad specificity to bacteria including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Mycobacterium avium (10–12). SP-D interacts with a variety of ligands on these microorganisms. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on UPEC is a likely ligand for SP-D because SP-D binds to the LPS moiety on E. coli (34). SP-D binds to specific O-antigens of the smooth form of LPS (35). The serotype of J96, which was used in this study, is O4:K6, making it a smooth strain. A previous study has shown that O4-specific polysaccharides from E. coli O4:K6 are composed of d-glucose, l-rhamnose, 2-acetamido-2,6-dideoxy-l-galactose, and 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-d-glucose (36). On the other hand, SP-D binds lipoarabinomannan on M. tuberculosis and M. avium (37–39) and lipids on Mycoplasma pneumonia (40). O-antigen, a glycolipid, or a lipid on UPEC could be a candidate for an SP-D ligand. An attempt to identify the SP-D ligand on UPEC is being made in our laboratory.

SP-D was incubated with UPEC, and the bacteria that bound to SP-D were sedimented. The complex of UPEC and SP-D was then used for bacterial adherence experiments (see Fig. 5). Incubation of the urothelial cells with the complex of SP-D and UPEC but not with UPEC alone inhibited bacterial adherence to the urothelial cells and the bacterium-induced cytotoxicity. Because SP-D agglutinates UPEC (see Fig. 4), it is likely that the agglutinated UPEC may not be able to adhere to the bladder urothelial cells. These results clearly indicate that the direct interaction of SP-D with UPEC protects the bladder cells against UPEC invasion.

We next focused on the interaction of SP-D with the bladder epithelium. UPIa on the urothelium possesses high mannose glycans and serves as a receptor for FimH, a lectin located at the tip of pili in UPEC (7). SP-D has been shown to interact with cell surface receptors including a receptor complex of Toll-like receptor 4 and MD-2, and signal-inhibitory regulatory protein α, resulting in regulation of inflammatory signals (25, 33). Therefore, we hypothesized that SP-D may interact with UPIa and affect the interaction of FimH with its receptor, UPIa. Because UPIa is expressed on the cell surface and possesses high mannose glycans only when it forms a heterodimeric complex with UPII (5), UPIa tagged with FLAG and UPII were co-expressed (see Fig. 7A). UPIa captured by an anti-FLAG antibody was used for the binding study of SP-D and FimH-RBD because of the difficulty of UPIa purification. As a control for UPIa, FLAG-tagged BAP was used. SP-D and FimH showed negligible binding to BAP captured by the anti-FLAG antibody, but SP-D and FimH significantly bound to UPIa captured by the antibody (see Fig. 7, B and C). Under these conditions, SP-D was found to compete with FimH for the binding to UPIa (see Fig. 7D). These results are consistent with those obtained from the experiments involving preincubation of the urothelial cells with SP-D followed by washing (see Fig. 6). After the urothelial cells were incubated with SP-D, the cells were washed to remove non-adherent SP-D and then infected with UPEC. The results indicated that SP-D inhibited the UPEC adherence to the urothelial cells and the bacterium-induced cytotoxicity. Taken together, competition of SP-D with FimH of UPEC for binding to cell surface receptor UPIa on urothelial cells is a likely mechanism by which the SP-D/urothelial cell interaction inhibits UPEC adherence.

SP-D is a member of the collectin group that prefers mannose ligands (10–14). SP-D activity is also sensitive to a variety of mannosides including α-methyl-mannoside, and any beneficial effects might be offset by deleterious effects on SP-D-dependent host defense (see Figs. 3, A and B, and 7B).

We finally conducted in vivo experiments using the UPEC infection model in mice. Consistent with the in vitro results, SP-D markedly decreased the adherence of UPEC to the bladder (see Fig. 8A) and dampened UPEC-induced inflammation (see Fig. 8B) in mice, indicating that SP-D can protect the bladder against UPEC infection. Because UTI by UPEC is one of the most common infections, there have been many attempts to overcome UTIs. In addition, the exogenously supplied SP-D decreases mortality of a mouse model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (41). SP-D may contribute to the prevention of not only local infections but also invasive infections. The present study indicates that the endogenous lectin SP-D possesses potential functions to protect the urinary tract against UPEC. Therefore, the exogenous administration of SP-D and/or an attempt to increase the SP-D expression in the urinary tract may be a therapeutic strategy to overcome UTIs.

In conclusion, SP-D decreases UPEC adherence to the bladder epithelial cells and UPEC-induced cytotoxicity both by direct interaction with UPEC and by competing with FimH for UPIa binding. This study demonstrates that SP-D can protect the bladder urothelium against UPEC infection and suggests a possible function of SP-D in the urinary tract.

Acknowledgments

The pGEX6-EGFP vector was a kind gift from Dr. Ikuo Wada (Fukushima Medical University School of Medicine, Fukushima, Japan). We also thank Dr. Shin-ichi Yokota and Dr. Kotaro Sugimoto (Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, Sapporo, Japan) for helpful suggestions in this study.

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan; by the Adaptable and Seamless Technology Transfer Program through Target-driven Research and Development from the Japan Science and Technology Agency, Japan; and by a grant from the Gohtaro Sugawara Research Fund for Urological Diseases.

- UTI

- urinary tract infection

- SP

- surfactant protein

- UPEC

- uropathogenic E. coli

- UP

- uroplakin

- RBD

- receptor-binding domain

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- BAP

- bacterial alkaline phosphatase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hooton T. M., Scholes D., Hughes J. P., Winter C., Roberts P. L., Stapleton A. E., Stergachis A., Stamm W. E. (1996) A prospective study of risk factors for symptomatic urinary tract infection in young women. N. Engl. J. Med. 335, 468–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Connell I., Agace W., Klemm P., Schembri M., Mrild S., Svanborg C. (1996) Type 1 fimbrial expression enhances Escherichia coli virulence for the urinary tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 9827–9832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lane M. C., Mobley H. L. (2007) Role of P-fimbrial-mediated adherence in pyelonephritis and persistence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) in the mammalian kidney. Kidney Int. 72, 19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mulvey M. A. (2002) Adhesion and entry of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Cell. Microbiol. 4, 257–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tu L., Sun T. T., Kreibich G. (2002) Specific heterodimer formation is a prerequisite for uroplakins to exit from the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 4221–4230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu X. R., Kong X. P., Pellicer A., Kreibich G., Sun T. T. (2009) Uroplakins in urothelial biology, function, and disease. Kidney Int. 75, 1153–1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhou G., Mo W. J., Sebbel P., Min G., Neubert T.A., Glockshuber R., Wu X. R., Sun T. T., Kong X. P. (2001) Uroplakin Ia is the urothelial receptor for uropathogenic Escherichia coli: evidence from in vitro FimH binding. J. Cell Sci. 114, 4095–4103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xie B., Zhou G., Chan S. Y., Shapiro E., Kong X. P., Wu X. R., Sun T. T., Costello C. E. (2006) Distinct glycan structures of uroplakins Ia and Ib: structural basis for the selective binding of FimH adhesin to uroplakin Ia. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 14644–14653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu X. R., Sun T. T., Medina J. J. (1996) In vitro binding of type 1-fimbriated Escherichia coli to uroplakins Ia and Ib: relation to urinary tract infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 9630–9635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Crouch E., Hartshorn K., Ofek I. (2000) Collectins and pulmonary innate immunity. Immunol. Rev. 173, 52–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crouch E., Wright J. R. (2001) Surfactant proteins A and D and pulmonary host defense. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 63, 521–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuroki Y., Takahashi M., Nishitani C. (2007) Pulmonary collectins in innate immunity of the lung. Cell. Microbiol. 9, 1871–1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Persson A., Chang D., Crouch E. (1990) Surfactant protein D is a divalent cation-dependent carbohydrate-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 5755–5760 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Day A. J. (1994) The C-type carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) superfamily. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 22, 83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kuroki Y., Voelker D. R. (1994) Pulmonary surfactant proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 25943–25946 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Crouch E., Chang D., Rust K., Persson A., Heuser J. (1994) Recombinant pulmonary surfactant protein D. Post-translational modification and molecular assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 15808–15813 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. LeVine A. M., Whitsett J. A., Gwozdz J. A., Richardson T. R., Fisher J. H., Burhans M. S., Korfhagen T. R. (2000) Distinct effects of surfactant protein A or D deficiency during bacterial infection on the lung. J. Immunol. 165, 3934–3940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hartshorn K. L., Crouch E., White M. R., Colamussi M. L., Kakkanatt A., Tauber B., Shepherd V., Sastry K. N. (1998) Pulmonary surfactant proteins A and D enhance neutrophil uptake of bacteria. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 274, L958–L969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu H., Kuzmenko A., Wan S., Schaffer L., Weiss A., Fisher J. H., Kim K. S., McCormack F. X. (2003) Surfactant proteins A and D inhibit the growth of Gram-negative bacteria by increasing membrane permeability. J. Clin. Investig. 111, 1589–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Madsen J., Kliem A., Tornoe I., Skjodt K., Koch C., Holmskov U. (2000) Localization of lung surfactant protein D on mucosal surfaces in human tissues. J. Immunol. 64, 5866–5870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stahlman M. T., Gray M. E., Hull W. M., Whitsett J. A. (2002) Immunolocalization of surfactant protein-D (SP-D) in human fetal, newborn, and adult tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 50, 651–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oberley R. E., Goss K. L., Dahmoush L., Ault K. A., Crouch E. C., Snyder J. M. (2005) A role for surfactant protein D in innate immunity of the human prostate. Prostate 65, 241–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sawada K., Ariki S., Kojima T., Saito A., Yamazoe M., Nishitani C., Shimizu T., Takahashi M., Mitsuzawa H., Yokota S., Sawada N., Fujii N., Takahashi H., Kuroki Y. (2010) Pulmonary collectins protect macrophages against pore-forming activity of Legionella pneumophila and suppress its intracellular growth. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 8434–8443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kingstone R. E., Kaurman R. J., Bebbington C. R., Rolfe M. R. (1992) in Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (Ausbel F. M., Brent R., Kingstone R. E., Moore D. D., Sediman L. G., Smith J. A., Struhl K., eds) Unit 16. 14, 16.14.1–16.14.13, John Wiley and Sons, New York [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamazoe M., Nishitani C., Takahashi M., Katoh T., Ariki S., Shimizu T., Mitsuzawa H., Sawada K., Voelker D. R., Takahashi H., Kuroki Y. (2008) Pulmonary surfactant protein D inhibits lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory cell responses by altering LPS binding to its receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35878–35888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ohya M., Nishitani C., Sano H., Yamada C., Mitsuzawa H., Shimizu T., Saito T., Smith K., Crouch E., Kuroki Y. (2006) Human pulmonary surfactant protein D binds the extracellular domains of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 through the carbohydrate recognition domain by a mechanism different from its binding to phosphatidylinositol and lipopolysaccharide. Biochemistry 45, 8657–8664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuroki Y., Honma T., Chiba H., Sano H., Saitoh M., Ogasawara Y., Sohma H., Akino T. (1997) A novel type of binding specificity to phospholipids for rat mannose-binding proteins isolated from serum and liver. FEBS Lett. 414, 387–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schembri M. A., Hasman H., Klemm P. (2000) Expression and purification of the mannose recognition domain of the FimH adhesin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 188, 147–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu J., Hu F., Liang W., Wang G., Singhal P. C., Ding G. (2010) Polymorphisms in the surfactant protein a gene are associated with the susceptibility to recurrent urinary tract infection in chinese women. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 221, 35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mason R. J., Nielsen L. D., Kuroki Y., Matsuura E., Freed J. H., Shannon J. M. (1998) A 50-kDa variant form of human surfactant protein D. Eur. Respir. J. 12, 1147–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oberley R. E., Goss K. L., Hoffmann D. S., Ault K. A., Neff T. L., Ramsey K. H., Snyder J. M. (2007) Regulation of surfactant protein D in the mouse female reproductive tract in vivo. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 13, 863–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oberley R. E., Goss K. L., Quintar A. A., Maldonado C. A., Snyder J. M. (2007) Regulation of surfactant protein D in the rodent prostate. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 5, 42–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gardai S. J., Xiao Y. Q., Dickinson M., Nick J. A., Voelker D. R., Greene K. E., Henson P. M. (2003) By binding SIRPα or calreticulin/CD91, lung collectins act as dual function surveillance molecules to suppress or enhance inflammation. Cell 115, 13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kuan S. F., Rust K., Crouch E. (1992) Interactions of surfactant protein D with bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Surfactant protein D is an Escherichia coli-binding protein in bronchoalveolar lavage. J. Clin. Investig. 90, 97–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sahly H., Ofek I., Podschun R., Brade H., He Y., Ullmann U., Crouch E. (2002) Surfactant protein D binds selectively to Klebsiella pneumonia lipopolysaccharides containing mannose-rich O-antigens. J. Immunol. 169, 3267–3274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jann B., Shashkov A. S., Kochanowski H., Jann K. (1993) Structural comparison of the O4-specific polysaccharides from E. coli O4:K6 and E. coli O4:K52. Carbohydr. Res. 248, 241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ferguson J. S., Voelker D. R., McCormack F. X., Schlesinger L. S. (1999) Surfactant protein D binds to Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli and lipoarabinomannan via carbohydrate-lectin interactions resulting in reduced phagocytosis of the bacteria by macrophages. J. Immunol. 163, 312–321 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kudo K., Sano H., Takahashi H., Kuronuma K., Yokota S., Fujii N., Shimada K., Yano I., Kumazawa Y., Voelker D. R., Abe S., Kuroki Y. (2004) Pulmonary collectins enhance phagocytosis of Mycobacterium avium through increased activity of mannose receptor. J. Immunol. 172, 7592–7602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ariki S., Kojima T., Gasa S., Saito A., Nishitani C., Takahashi M., Shimizu T., Kurimura Y., Sawada N., Fujii N., Kuroki Y. (2011) Pulmonary collectins play distinct roles in host defense against Mycobacterium avium. J. Immunol. 187, 2586–2594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chiba H., Pattanajitvilai S., Evans A. J., Harbeck R. J., Voelker D. R. (2002) Human surfactant protein D (SP-D) binds Mycoplasma pneumoniae by high affinity interactions with lipids. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 20379–20385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Madan T., Kishore U., Singh M., Strong P., Hussain E. M., Reid K. B., Sarma P. U. (2001) Protective role of lung surfactant protein D in a murine model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Infect. Immun. 69, 2728–2731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]