Background: The ATP synthase of Pyrococcus has an unusual gene encoding rotor subunit c.

Results: The c ring is made of protomers with one ion-binding site in four transmembrane helices and is highly Na+-specific.

Conclusion: Unprecedented subunit c topology and ion configuration in an ATP synthase.

Significance: Archaeal ATP synthases are a remnant of primordial bioenergetics.

Keywords: Archaea, ATP Synthase, Homology Modeling, Membrane Proteins, Sodium Transport, <I>c</I> Ring, Ion-binding Site

Abstract

The ion-driven membrane rotors of ATP synthases consist of multiple copies of subunit c, forming a closed ring. Subunit c typically comprises two transmembrane helices, and the c ring features an ion-binding site in between each pair of adjacent subunits. Here, we use experimental and computational methods to study the structure and specificity of an archaeal c subunit more akin to those of V-type ATPases, namely that from Pyrococcus furiosus. The c subunit was purified by chloroform/methanol extraction and determined to be 15.8 kDa with four predicted transmembrane helices. However, labeling with DCCD as well as Na+-DCCD competition experiments revealed only one binding site for DCCD and Na+, indicating that the mature c subunit of this A1AO ATP synthase is indeed of the V-type. A structural model generated computationally revealed one Na+-binding site within each of the c subunits, mediated by a conserved glutamate side chain alongside other coordinating groups. An intriguing second glutamate located in-between adjacent c subunits was ruled out as a functional Na+-binding site. Molecular dynamics simulations indicate that the c ring of P. furiosus is highly Na+-specific under in vivo conditions, comparable with the Na+-dependent V1VO ATPase from Enterococcus hirae. Interestingly, the same holds true for the c ring from the methanogenic archaeon Methanobrevibacter ruminantium, whose c subunits also feature a V-type architecture but carry two Na+-binding sites instead. These findings are discussed in light of their physiological relevance and with respect to the mode of ion coupling in A1AO ATP synthases.

Introduction

Archaea produce ATP using an ATP synthase that is distinct from the well known F1FO ATP synthase found in bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts (1). Archaeal A1AO ATP synthases are evolutionary more closely related to vacuolar V1VO ATPases, notwithstanding the fact that these act as ATP-driven ion pumps and are therefore functionally different (2–4). Like F-ATP synthases and V-ATPases, A-ATP synthases comprise a membrane motor, AO, which is driven by downhill translocation of H+ or Na+, and a soluble domain, A1, where ATP is synthesized from ADP and Pi. A1 and AO are mechanically coupled by three protein stalks: one central and two peripheral. Under suitable conditions A1 can also hydrolize ATP and function as a motor for uphill ion translocation across AO (2, 5, 6).

The membrane-bound AO motor contains subunits a and c (2, 7). Subunit c consists at least of two transmembrane helices and is expressed in multiple copies, which form a ring-like structure that, like the FO motor (8), functions as a rotating turbine driven by the movement of ions across the membrane. In most A-type ATP synthases, subunit c has a single-hairpin topology as seen in F-type ATP synthases. By contrast, in V-type ATPases (9, 10) the c subunit apparently underwent gene duplication, resulting in a protein with four transmembrane helices (11). Moreover, one ion-binding site was lost during the duplication event leading to a rotor with only half the number of ion-binding sites. These missing binding sites have been seen as the reason for the inability of V-ATPases to act as ATP synthases. Instead, the rotor favors generation of large ion gradients, a function important for the cellular physiology of eukaryotes (3, 4).

In recent years, however, the determination of the genome sequences of several archaea have revealed an unexpected feature of A1AO ATP synthases: the gene encoding for subunit c underwent duplication (12, 13), triplication (14), and even greater multiplication, so far up to 13-fold (15–17). Moreover, in some species the sequence motif characteristic of the ion-binding site is absent in one hairpin, which would result in c subunits with one ion-binding site within four transmembrane helices or two within six transmembrane helices (10, 18). In particular, the DNA data for Pyrococcus furiosus implies that its c subunit has a typical V-type topology with two hairpins but only one Na+-binding site per subunit (10, 19). The implication, according to common wisdom, would be that the enzyme lost its function as an ATP synthase. However, the A1AO ATP synthase from P. furiosus is the only ATP synthase encoded in the genome and functions as an ATP synthase in vivo (19, 20).

The structural rationale for the ATP synthesis activity of the P. furiosus enzyme, despite the predicted V-type c subunit, is unknown. It could involve post-transcriptional modifications as well as additional, yet hidden ion-binding sites in the mature protein. Because the primary structure and number of ion-binding sites are assumed based on predictions from the DNA sequence, it was important to isolate the mature c subunit and determine experimentally its primary structure, molecular mass, and ion-binding sites. These studies culminate in a three-dimensional computational model of the c ring from P. furiosus, which provides a structural interpretation for our biochemical experiments, and enables us to assess the physiological ion specificity of this and other archaeal A1AO ATP synthases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strain and Cultivation Condition

P. furiosus DSM 3638 was obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung für Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (Braunschweig, Germany) and was grown anaerobically in a 300 liter enamel-coated fermenter at 98 °C in medium without sulfur, but with yeast extract, starch, and pepton as energy source and N2/CO2 (80:20, v/v) as described before (21). The cells were harvested and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Membrane Preparation and Protein Determination

20–40 g of P. furiosus cells (wet weight) were resuspended in buffer A (25 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm PMSF) containing 0.1 mg DNase I/ml. The cells were homogenized and disrupted by three passages through a French pressure cell (Aminco) at 3000 p.s.i. Cell debris and the thermosome, a cytoplasmatic heat shock protein present at high temperatures, were removed by four centrifugation steps (Beckman Avanti J-25, JA 14 rotor; 7,500, 7,900, 8,200, and 8,500 rpm each for 20 min at 4 °C). The membranes were sedimented from the crude extract by centrifugation (Beckman Optima L90-K, 50.2 Ti rotor; 12,000 rpm for 16 h at 4 °C) and were washed with buffer B (100 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 5% glycerol (v/v), 100 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm PMSF). The washed membranes were collected by centrifugation (Beckman Optima L90-K, 50.2 Ti rotor; 16,000 rpm, 5 h, 4 °C) and resuspended in buffer C (100 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 5% glycerol (v/v), 0.1 mm PMSF), and the protein concentration was determined as described (62).

Purification of the A1AO ATP Synthase

Washed membranes were resuspended in buffer C and used for membrane protein solubilization. Triton X-100 was added to a concentration of 3% (v/v) (1 g of Triton X-100/g of membrane protein), and membranes were incubated for 2 h at 40 °C and then overnight at room temperature under shaking. The membranes were collected by ultracentrifugation (Beckman Optima L90-K, TFT 65.13 rotor; 42,000 rpm for 2 h at 4 °C), and contaminating proteins were precipitated with PEG 6000 (4.1%, w/w) for 30 min at 4 °C. The precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation (Beckman Optima L90-K, TFT 65.13 rotor; 38,000 rpm for 2 h at 4 °C), and the supernatant was loaded onto a sucrose gradient (20–66%) and centrifuged for 19 h in a vertical rotor (Beckman Optima L90-K, VTi50 rotor; 43,000 rpm at 4 °C). ATP hydrolysis activity of each sucrose gradient fraction was tested as described before (21). Fractions with the highest ATPase activity were pooled and applied to anion exchange chromatography using DEAE-Sepharose, which was equilibrated with buffer D (50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.1 mm PMSF, 0.1% (v/v) reduced Triton X-100). A salt gradient (0–1 m NaCl) in buffer D was used for protein elution at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Fractions with the highest ATPase activity were pooled, concentrated (molecular mass cutoff, 100 kDa), and applied to gel filtration using a Superose 6 column (10/300 GL; GE Healthcare). Gel filtration was performed in buffer E (50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.1 mm PMSF, 0.05% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside) at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min. Again, fractions with the highest ATP hydrolysis activity were pooled.

Chloroform/Methanol Extraction of Subunit c of Membranes from P. furiosus

The membranes resuspended in buffer C were mixed with 20 volumes of chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) for 20 h at 4 °C and filtered. 0.2 volume of H2O was added to the filtrate and mixed for another 20 h at 4 °C. The organic phase was separated from the aqueous and interphase using a separation funnel and was washed twice with 0.5 volume of chloroform/methanol/H2O (3:47:48, v/v/v). The washed organic phase was filled up with 1 volume of chloroform. Methanol was added until the turbid solution cleared up. The volume of the solution was reduced to 1 ml using vacuum evaporation. Protein was precipitated with 4 volumes of diethylether at −20 °C for 12 h and sedimented by centrifugation (Eppendorf 5417R, FA-45–24-11 rotor; 8,000 rpm at −8 °C). Sedimented protein was resolved in 1 ml of chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v).

N,N′-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide Labeling Experiments

For labeling experiments with N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCD, dissolved in ethanol),3 purified A1AO ATP synthase was used. 1 ml of ATP synthase was dialyzed in a dialysis tube (molecular mass cutoff, 3.5 kDa) against 1000 ml of buffer F (25 mm Tris, 25 mm MES, 5 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol) adjusted to pH 5.5, 6.0, or 6.5 with HCl or KOH for 12 h at 4 °C. 20 μl of ATP synthase (9 μg of protein) was incubated with 250 or 500 μm DCCD at pH levels of 5.5, 6.0, or 6.5 for 60 min at room temperature. For competition experiments between DCCD and NaCl or KCl, the salts were added to the ATP synthase solution in concentrations of 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, or 25 mm, directly before labeling. After labeling with DCCD, the ATP synthase was purified using C4 Zip Tips to remove excessive DCCD and salts. The C4 matrix (bed volume, 0.6 μl) of a 10-μl Zip Tip was first equilibrated with 20 μl of 100% acetonitrile and 20 μl of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. ATP synthase was coupled to the equilibrated matrix and washed with 30 μl of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The A1A0 ATP synthase was eluted with 10 μl of 90% acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. To desintegrate the ATP synthase and the c ring of P. furiosus into c monomers, 10 μl of chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) was added and mixed. The solution containing the c monomers were dried by vacuum evaporation for 1.5 h at room temperature. The dried protein pellet was mixed with 1 μl of 2,5-dihydroxyacetophenone matrix and applied to MALDI-TOF-MS as described below.

MALDI-TOF-MS Measurements

Chloroform/methanol extracts for protein m/z determination were mixed in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio with matrix 2,5-dihydroxyacetophenone (15 mg/ml 2,5-dihydroxyacetophenone in 75% ethanol in 20 mm sodium citrate; Bruker Daltonics) or 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (30 mg of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid/100 μl of TA solution (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid/acetonitrile, 1:2 (v/v); Bruker Daltonics)) and spotted on ground steel target plates (Bruker Daltonics). MALDI mass spectra were recorded in a mass range of 5–20 kDa using a Bruker Autoflex III Smartbeam mass spectrometer. Detection was optimized for m/z values between 5 and 20 kDa and calibrated using calibration standards (protein molecular weight calibration standard 1; Bruker Daltonics).

Protein Identification and Quantification Using Mass Spectrometry (Peptide Mass Fingerprinting)

Chloroform/methanol extracts of P. furiosus membranes were mixed in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio with 20 mm MES, pH 5.5, containing 0.5% n-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside, and the organic phase was removed by a gentle N2 stream until the turbid solution was getting clear. The protein extract was then submitted to 12.5% SDS-PAGE (22) and stained with silver, suitable for mass spectrometry (23). Bands of interest were excised, reduced, alkylated, and digested using trypsin, chymotrypsin or both proteases according to standard mass spectrometry protocols (24). Proteolytic digests were applied to reverse phase columns (trapping column C18: particle size, 3 μm; length, 20 mm; and analytical column C18: particle size, 3 μm; length, 10 cm) (NanoSeparations, Nieuwkoop, Netherlands) using a nano-HPLC (Proxeon easy nLC), eluted in gradients of water (0.1% formic acid, buffer A) and acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid, buffer B) in 50 min at flow rates of 300 nl/min and ramped from 5 to 65% buffer B. Eluted peptides were ionized using a Bruker Apollo electrospray ionization source with a nanoSprayer emitter and analyzed in a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Bruker maxis). The proteins were identified by matching the mass lists on a Mascot server (version 2.2.2; Matrix Science) against NCBInr database.

Modeling of the P. furiosus c Ring Structure

Homologous sequences of the P. furiosus target c subunit sequence were obtained after five PSI-BLAST iterations (25) on the nonredundant database, using 0.001 as the E-value cutoff. For scoring we used the BLOSUM62 matrix (26), a gap open penalty of 11 and a gap extension penalty of 1. The results were then clustered at 65% sequence identity using CD-HIT (27, 28). Representative sequences of each cluster, plus target and template sequences, were used as input for a multiple alignment, using T-Coffee (29). The pairwise target-template alignment used for homology modeling was derived from this multiple alignment. Two-thousand structural models of the c10 ring of P. furiosus were constructed using the structure of the c ring from Enterococcus hirae V-type ATPase (30) as template (Protein Data Bank entry 2BL2; 36% sequence identity with P. furiosus c subunit). Modeler 9v8 was employed to generate these models. The scoring functions GA341 (31) and DOPE (discrete optimized potential energy) (32) were used to select the best three models. The coordinates of the bound Na+ were translated from the template to the target structure. Secondary structure and transmembrane predictions for the P. furiosus c ring, obtained with Psipred v2.5 (33) and TopCons (34), respectively, were compared with the actual secondary structure (determined with the DSSP algorithm (35)) and transmembrane spans (estimated with OPM (36)) of the template.

Modeling of a c3 Subconstruct of the c Ring of Methanobrevibacter ruminantium

A pairwise alignment of M. ruminantium target sequence with the c subunit from E. hirae (33% sequence identity) was generated as for the P. furiosus sequence. We then generated and selected the best model of a c3 subconstruct of M. ruminantium in the same manner as explained previously for the P. furiosus c10 ring (the stoichiometry of M. ruminantium c ring is unknown). Secondary structure and transmembrane predictions for the target were compared with the secondary structure and transmembrane regions of the template as mentioned above.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Calculations of the Ion Selectivity of the c Ring Binding Sites

The c10 rings of E. hirae and P. furiosus and the c3 construct of M. ruminantium were inserted in a hydrated palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylcholine membrane (540, 542, and 189 lipid molecules and 38499, 38319, and 11763 water molecules, respectively), using GRIFFIN (37). The c10 rings have a single Na+ in each c subunit, coordinated by Glu-139/Glu-142. The c3 construct of M. ruminantium, however, carries one Na+ coordinated by Glu-140 in each c subunit and another coordinated by Glu-59 in between adjacent c subunits. The protein/membrane systems were equilibrated using constrained all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. The strength of the constraints on the protein were gradually weakened over 12 ns for the c10 rings and 7 ns for the c3 construct. Subsequently, unconstrained simulations were carried out for 40 and 10 ns, respectively. The conformations obtained after the unconstrained equilibrations were used as input of all-atom free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations of the exchange between Na+ and H+ in each binding site and vice versa. The FEP calculations were performed in the forward and backward direction, in 32 intermediate steps; each of these steps consists of 500 ps of sampling time, including 100 ps of equilibration. Both molecular dynamics and FEP calculations were carried out with NAMD2.7 (38) using the CHARMM27 force field for proteins and lipids (39, 40). All simulations were at constant pressure (1 atmosphere) and temperature (298 K), and with periodic boundary conditions in all directions. The dimensions of the simulation box in the plane of the membrane (150 × 150 Å for the c10 rings and 72 × 96 Å for the c3 construct) were kept constant. The particle mesh Ewald method was used to compute the electrostatic interactions, with a real space cutoff of 12 Å. A cutoff of 12 Å was also used for van der Waals interactions, computed with a 6–12 Lennard-Jones potential. During the molecular dynamics and FEP simulations of the M. ruminantium c3 construct, the conformations of the first (residues 6–77) and last hairpins (residues 86–161) were preserved using a weak harmonic restraint on the root mean square deviation of the backbone, relative to the initial model.

RESULTS

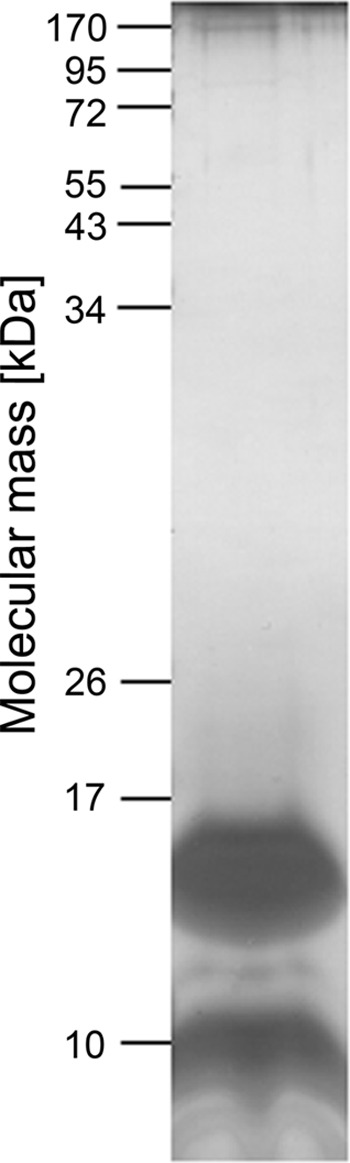

Purification of Subunit c and Mass Determination

Subunit c of ATP synthases/ATPases is a very hydrophobic protein that can be isolated from membranes using organic solvents such as chloroform/methanol (12, 41, 42). Membranes of P. furiosus were thus extracted by chlorofom/methanol, and the extract was applied to an SDS gel. As can be seen in Fig. 1, this procedure yielded two bands with apparent molecular masses of 16 and 10 kDa. To identify these proteins, peptide mass fingerprinting was used, and their molecular masses were determined by MALDI-TOF-MS. Analysis of the 10-kDa band showed that it actually consists of two proteins. One is the subunit K of the RNA polymerase (PF1642) with an apparent molecular mass of 6,269 Da, and the other is subunit F of a putative monocation/H+ antiporter (PF1452) with an apparent mass of 9,076 Da. The 16-kDa band in the SDS gel was identical to subunit c of the A1AO ATP synthase (PF0178). Its apparent molecular mass was 15,853 Da, which matches almost exactly the mass deduced from the genome sequence (Mr = 15,806). The difference in the molecular mass, of around 50 Da, is likely caused by a low signal intensity of the peak and multiple nonresolved oxidations of subunit c. Nevertheless, this is evidence that the mature c subunit of P. furiosus is indeed a duplication of the “classical” 8-kDa c subunit of F-type ATP synthases.

FIGURE 1.

Protein composition of the chloroform/methanol extract. The extract was subjected to SDS-PAGE on 12.5% gels and stained with silver. On the left, molecular mass markers are provided.

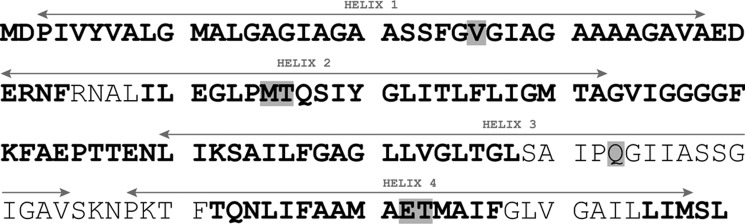

Validation of the Amino Acid Sequence Predicted from DNA Data

Peptide mass fingerprinting was used to verify the predicted sequence of the P. furiosus subunit c (Fig. 2). Subunit c was digested by trypsin, chymotrypsin, and a combination of both, and the fragments were analyzed by electrospray ionization-MS. The sequence coverage was 78.6%, and only one large fragment, from Ser-109 to Phe-131, was not resolved. The experimental data not only verified the predicted start codon but also unequivocally confirmed the predicted amino acid sequence. As will be discussed later, the absence of a glutamine at position 26 (replaced by valine) and a glutamate at position 55 (replaced by methionine) are particularly noteworthy. Of special interest is the presence of a second glutamate at position 51.

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of amino acid sequence of subunit c of P. furiosus. To analyze the amino acid sequence of subunit c, the protein was excised from 12.5% silver-stained gels, destained, reduced, alkylated, and digested using trypsin, chymotrypsin, or both proteases. The amino acids whose identities were determined are marked in bold type. Those potentially involved in ion-binding sites are shaded in grey.

Quantitative DCCD Labeling Indicates That Each c Subunit Carries a Single Na+ Site

DCCD inhibits ATP synthases/ATPases by covalently binding to a key carboxylate side chain found in the ion-binding sites in the c subunit. In H+-driven ATP synthases, this carboxylate is the site of H+ binding, through protonation (43). In Na+-coupled c subunits, this side chain can also be protonated in the absence of Na+, but otherwise it is deprotonated and coordinates the Na+ directly (30, 44, 45). DCCD reacts with this carboxylate side chain only in its protonated state; therefore, in Na+-driven c subunits, DCCD and Na+ compete for this common binding site, in a manner that is pH-dependent (46, 47). Thus, a DCCD labeling assay can in principle be used to quantify the number of ion-binding sites in the c subunit, as well as to reveal whether or not they bind Na+.

We first measured DCCD labeling to individual c subunits extracted with chloroform/methanol from P. furiosus membranes. The c subunits were transferred from the organic phase to a water phase with different pH levels of 5.5, 7.0, and 10.0 (25 mm MES, pH 5.5, Tris, pH 7.0, CHES, pH 10.0, containing 1% n-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside) by mixing both phases and removing the chloroform/methanol by a N2 stream, because the DCCD labeling reaction does not proceed readily in this organic solvent. After the addition of 500 μm DCCD, samples (1 μl of sample mixed with 1 μl of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid) were taken at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 150 min and examined with MALDI-TOF-MS. This analysis revealed one DCCD molecule bound to each c subunit, as is evident from the increase in molecular mass by 206 Da, which corresponds to one molecule of DCCD. DCCD labeling was time-dependent (34% after 30 min, 46% after 60 min, and 53% after 90 min) and dependent on pH. Labeling was only observed at pH 5.5 and not at pH 7.0 or 10.0.

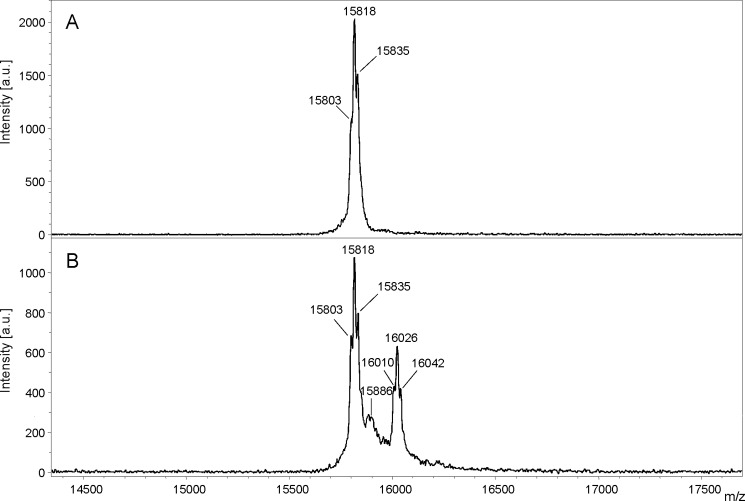

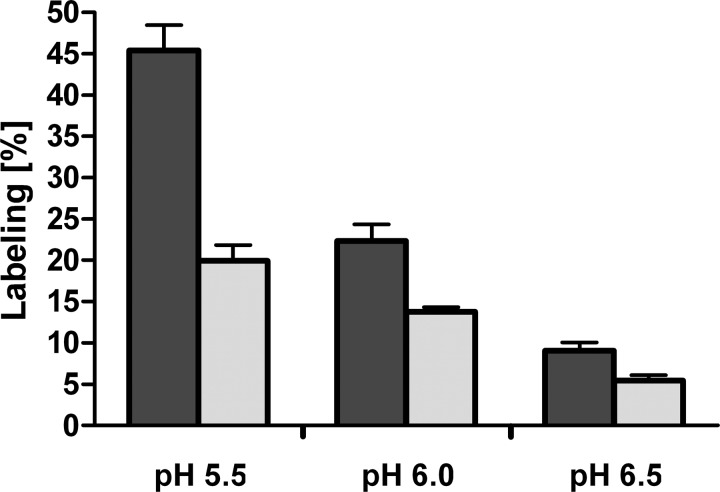

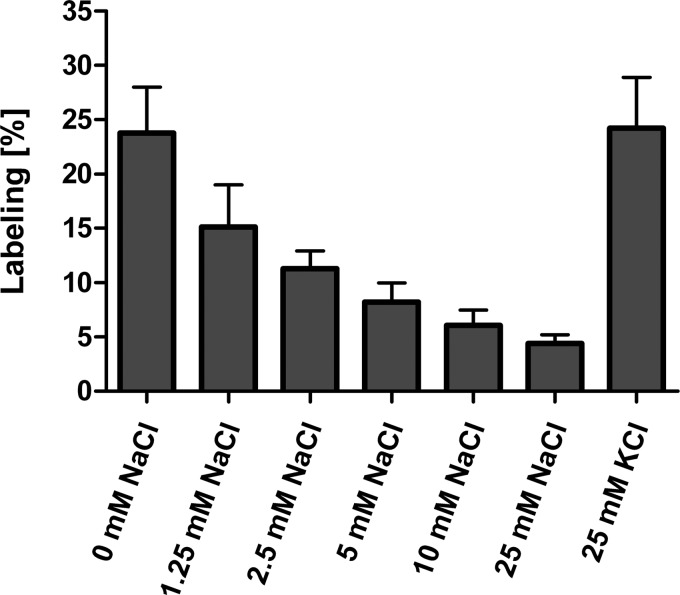

Unfortunately, DCCD labeling of c subunits isolated by chloroform/methanol was not protected by NaCl, even when smaller amounts of DCCD (50 or 100 μm) were used. This is likely due to the partial unfolding of subunit c as a result of the harsh purification procedure in chloroform/methanol. Instead, we labeled the purified A1AO ATP synthase with DCCD, and the c subunit was isolated by chloroform/methanol afterwards. Upon incubation of the enzyme with DCCD, the molecular mass of subunit c increased from 15,803 to 16,010 Da (for the unoxidized protein), from 15,818 to 16,026 Da (for the one time oxidized protein), and from 15,835 to 16,042 Da (for the two times oxidized protein), indicating again that one c subunit had bound one DCCD molecule (Fig. 3). The extent of DCCD labeling was clearly dependent on the DCCD concentration and the pH used (Fig. 4). The labeling efficiency with 500 μm DCCD after 60 min was roughly twice that observed with 250 μm, for the same pH. For the same DCCD concentration, the labeling efficiency at pH 6.5 was one-fourth of that at pH 5.5. Again, only one DCCD-reactive site was identified. Crucially, DCCD labeling was prevented by Na+, but not K+ (Fig. 5). The competing effect of Na+ on DCCD modification was clearly pH-dependent: the higher the pH, the less Na+ was required to prevent DCCD labeling.

FIGURE 3.

Subunit c of P. furiosus binds one DCCD. Purified A1AO ATP synthase/ATPase of P. furiosus was incubated with 250 μm DCCD at room temperature for 60 min. Subunit c was extracted by chloroform/methanol from unlabeled (A) and DCCD-labeled (B) ATP synthase/ATPase. The molecular mass of both c subunits was determined by MALDI-TOF-MS.

FIGURE 4.

pH- and dosis-dependent DCCD labeling of subunit c. The purified A1AO ATP synthase of P. furiosus was incubated with 250 μm DCCD (light gray bars) or 500 μm DCCD (dark gray bars) at room temperature and at pH 5.5, 6.0, or 6.5 for 60 min. Subunit c was extracted by chloroform/methanol and examined with MALDI-TOF-MS.

FIGURE 5.

DCCD labeling of subunit c is Na+-dependent. The purified A1AO ATP synthase of P. furiosus was incubated with different concentrations of NaCl or KCl and labeled with 250 μm DCCD at room temperature and at pH 5.0 for 60 min. Then subunit c was extracted by chloroform/methanol and examined with MALDI-TOF-MS.

Structural Model of the c Ring of P. furiosus with Its Na+-binding Sites

After the primary structure predicted from the DNA sequence had been verified, we generated a structural model of the c ring of P. furiosus. The model is based on the structure of the c ring from E. hirae, which also consists of V-type c subunits. Supplemental Fig. S1 shows the alignment of the c subunit sequences from the V-type ATPase from E. hirae and the A-type ATP synthase from P. furiosus. The known secondary structure and the transmembrane spans (TM1 to TM4) of the E. hirae c subunit match well those predicted for the P. furiosus sequence. Furthermore, given that laser-induced liquid beam ion desorption-mass spectroscopy (LILBID-MS) data suggest that the c ring of P. furiosus assembles as decamer (7), it is reasonable to employ the crystallographic structure of the c10 rotor from E. hirae (30) as a template to model the archaeal ring.

As explained under “Experimental Procedures,” we produced a large ensemble of tentative models and ranked them according to two independent scoring functions, namely DOPE and GA341. Among these, we selected the two models with top ranks according to either score, plus a third one that was also highly ranked in both scoring schemes. For all of them, the GA341 score was >0.8 (the closer to 1, the better is the model). All these three models are highly similar in their transmembrane region (Cα-trace root mean square deviation, ∼1.2 Å) but differ elsewhere (root mean square deviation, ∼9 Å). Mostly they vary in the long loop that connects the second and third transmembrane spans, where there is a gap in the target-template alignment. Importantly, the ion-binding sites, clearly located within the membrane domain, do not vary significantly in the different models. In sum, given the high confidence in the sequence alignment, the quality of the template structure, and the convergence in the calculations toward a unique prediction, we expect these models of the P. furiosus c ring to be very realistic, particularly in the transmembrane domain.

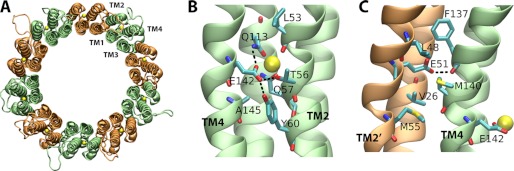

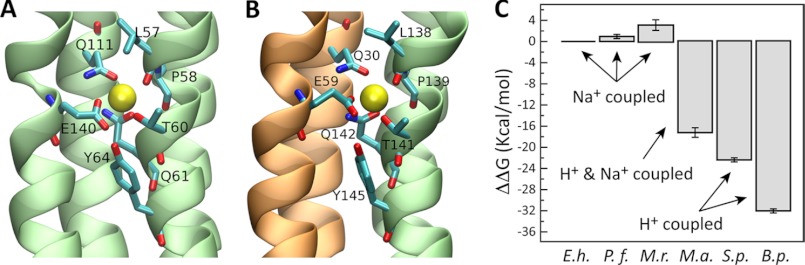

One of these equivalent models is depicted in Fig. 6. The model is perfectly consistent with the notion that ATP synthesis in this archaeon is driven by Na+ gradients. The ion-binding sites are located within each c subunit, flanked by TM2 and TM4 (Fig. 6B). The Na+ is coordinated by the side chains of Glu-142 (TM4), Gln-113 (TM3), Thr-56 (TM2), and Gln-57 (TM2) and by the backbone of Leu-53 (TM2). In addition, the side chain of Tyr-60 (TM2) forms a hydrogen bond with Glu-142 and contributes to stabilize the geometry of the ion coordination shell. This network of interactions is identical to that revealed by the crystal structure of the c10 rotor from the E. hirae V-type ATPase, which has been established to function as a Na+ pump under physiological conditions (48).

FIGURE 6.

Structural model of the c10 rotor from the A1AO ATP synthase from P. furiosus. A, view of the complete c10 ring from P. furiosus, from the periplasmic side. The bound sodium ions are shown as yellow spheres; alternate colorings (orange and green) indicate different c subunits. B, close-up view of the Na+-binding site, flanked by TM4 and TM2 within each c subunit. Residues involved in ion coordination are highlighted. Hydrogen bonds are indicated with dashed lines. C, close-up view of the interface between TM2′ and TM4 in adjacent c subunits, at the level of the Na+-binding sites in B. Hydrophobic side chains in this region are indicated. Also, note the protonated Glu-51 side chain, one helix turn away, toward the cytoplasmic side. This side chain hydrogen bonds to a carbonyl group in the backbone of TM4.

As mentioned, the c subunit from the P. furiosus ATP synthase also resembles that from the E. hirae ATPase in that it consists of four transmembrane helices. It is therefore reasonable to ask whether Na+-binding sites may be found not only within each c subunit, but also in between them, as occurs in rotor rings whose c subunits have a two-helix topology (49). Our structural model suggests that this is highly unlikely, because this region is markedly hydrophobic, namely Val-26 (TM1′), Leu-48 (TM2′), Met-55 (TM2′), and Met-140 (TM4) (Fig. 6C). Such an environment could not possibly counter the cost of dehydration incurred upon Na+ binding within the membrane domain. Consistently, the analogous location in the crystal structure of the E. hirae rotor lacks a bound Na+; in that structure, all of these hydrophobic residues are conserved, except for Met-55, which is substituted by Gly-63.

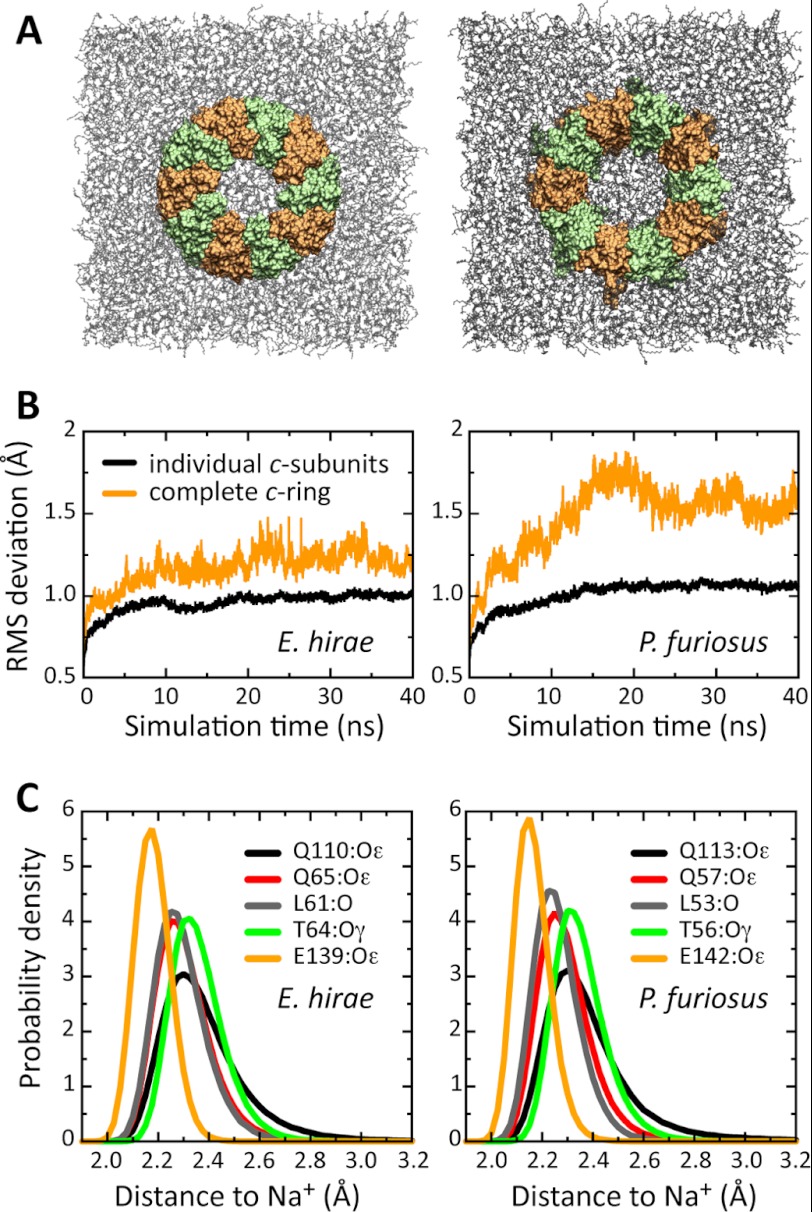

Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the P. furiosus c Ring in the Membrane

To further assess the verisimilitude of the c10 model of the P. furiosus c ring, we carried out a molecular dynamics simulation of this model embedded in a phospholipid membrane and compared the outcome with an analogous simulation of the c ring from the E. hirae ATPase (Fig. 7A). The rationale here is that if the model is a realistic approximation of the actual structure, its behavior in simulation ought to be comparable with that of an experimentally determined structure. What we observe is that the dynamical range of the individual c subunits is essentially identical when comparing the model from P. furiosus and the structure from E. hirae (Fig. 7B). Likewise, the structure and dynamics of the Na+-binding sites in both c rings are largely undistinguishable (Fig. 7C). These results indicate that the internal structure of the c subunits in the P. furiosus model is indeed very plausible. The relative orientation of the c subunits in the initial model of the ring, however, seems to be somewhat suboptimal. In the first half of the simulation, the structure of the ring as a whole departs from the starting model more than the c ring from E. hirae does, i.e., more than the magnitude of the natural room temperature fluctuations. Nevertheless, also this overall structural arrangement becomes stable in the second half of the simulation (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Molecular dynamics simulations of the c rings from P. furiosus and E. hirae in a lipid membrane. A, simulation systems for the c rings from the E. hirae ATPase (left panel) and the P. furiosus ATP synthase (right panel), each embedded in a phospholipid membrane (gray). The individual c subunits are colored alternately (orange and green). Water molecules and other details are omitted for clarity. The view is from the cytoplasmic side. B, variability in the structure of the c rings during the simulation, in terms of the root mean square (RMS) difference relative to the starting structure. The data are shown for the rings evaluated as a whole and for the c subunits analyzed individually and then averaged. C, ion-protein coordination distances in the Na+-binding site, shown as probability distributions. The distributions derive from the complete time span of the simulation, i.e., they reflect not only the variability among different binding sites in the ring but also the structural dynamics of each site.

A Second, Constitutively Protonated Glutamate within the Membrane Domain

A noteworthy feature of the P. furiosus sequence is the presence of a second glutamate side chain in TM2′ (Glu-51), one helix turn toward the cytoplasmic side of the rotor (Fig. 6C). Could this be a second ion-binding site? Our model suggests that this side chain is constitutively protonated and that it contributes to the stability of the interface between adjacent c subunits in the assembled ring, by forming a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl group of residue Phe-137 (in TM4). Consistently, this nonconserved side chain is replaced by glutamine in homologous sequences, for example in E. hirae. Indeed, in the crystal structure of the E. hirae rotor, this glutamine side chain is seen to form the same interaction, across from TM2′ to TM4 of the adjacent c subunit. Therefore we hypothesize that protonation of Glu-51 is structurally important, but not functionally relevant.

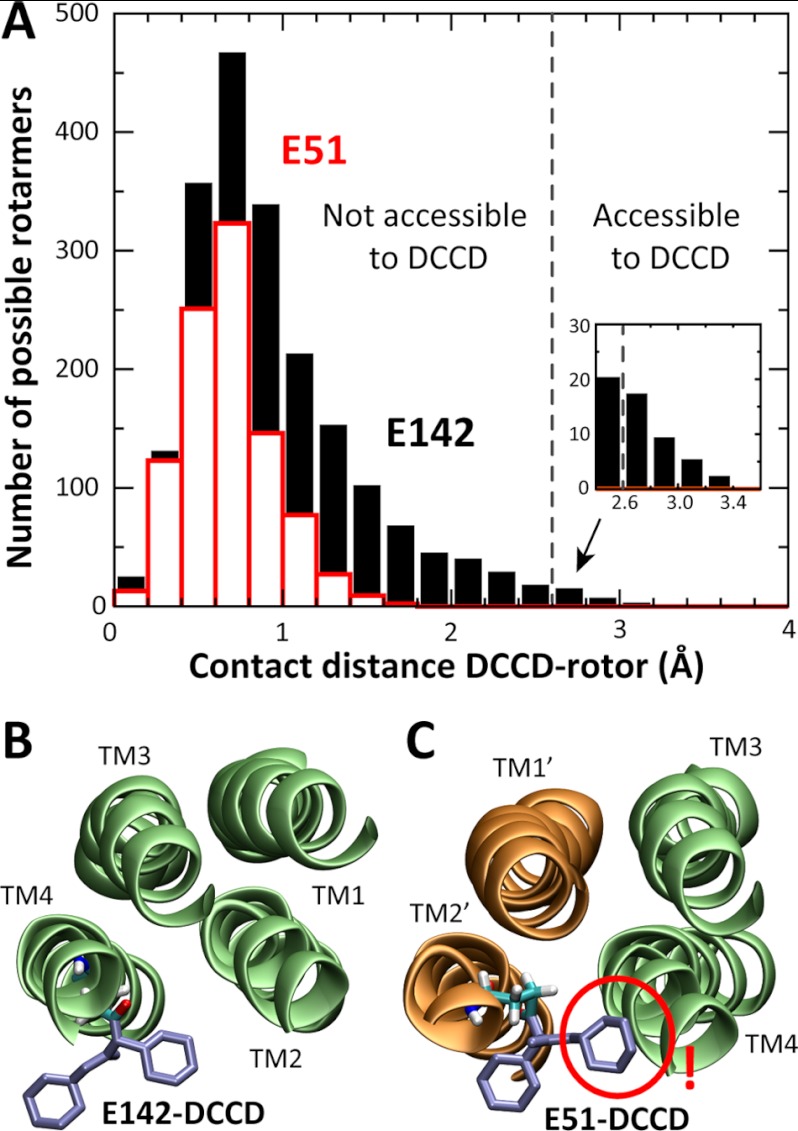

In support of this view, DCCD labeling of the assembled rotor results in one residue modification per subunit (Fig. 3). Based on our structural model, we interpret this result to reflect the reaction of DCCD with Glu-142, which can be expected to be transiently protonated at low Na+ concentrations, rather than the modification of Glu-51. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 8, DCCD modification is structurally viable in the case of Glu-142, upon an outwards rotation of the carboxylate group. This minor but necessary rearrangement is essentially identical to that seen in crystal structures of DCCD-modified c rings (50, 51). In the case of Glu-51, however, we find that DCCD modification would be sterically impossible in all rotamers of the side chain (in χ1, χ2, and χ3). Thus, Glu-51 cannot be modified in the context of the assembled rotor. Consistent with this interpretation, increasing concentrations of Na+ inhibit DCCD labeling of the rotor (Fig. 5), because Na+ binding precludes protonation of Glu-142 (but not Glu-51).

FIGURE 8.

DCCD accessibility to Glu-142 and Glu-51. A, two libraries of 5832 possible rotamers of DCCD-modified Glu-142 and Glu-51 were created by rotation of χ1, χ2, and χ3 angles (in 18° increments). For each rotamer, the contact distance between DCCD and the rest of the protein was computed. DCCD modification can occur only if the resulting contact distance is larger than ∼2.5 Å. B and C, two snapshots of the rotamer libraries generated for Glu-142 and Glu-51. The conformation in B is very similar to that found in crystal structures of DCCD-modified rotor rings; in C, the DCCD label clashes with the outer helices TM2′ and TM4.

P. furiosus Is Not the Only Archaeon That Has a 16-kDa c Subunit with Only One Na+-binding Site

An alignment of all c subunit sequences available for archaea (supplemental Fig. S2) indicates that c subunits with four transmembrane helices are found in Crenarchaeota and Euryarchaeota, but not in Korarchaeota and Thaumarchaeota. Pyrococci and Thermococci are the only archaea of the Euryarchaeota with a c subunit containing four transmembrane helices and a single Na+-binding site between TM2 and TM4 of the same subunit, like P. furiosus. In the Crenarchaeota phylum, the Desulfurococci and Staphylothermus species, as well as Ignisphaera aggregans, also feature a duplicated c subunit with a single Na+-binding site. Interestingly, among the archaeal c subunits with four transmembrane helices, only those from methanogens contain two Na+-binding sites per c subunit. Methanobrevibacter, Methanothermobacter, and Methanobacterium species, as well as Methanosphaera stadtmanae, feature a binding site analogous to that in P. furiosus, i.e., formed within the c subunit, and a second one, identical in its amino acid composition, which would appear between adjacent c subunits in the assembled ring, i.e., mediated by a glutamate in TM2, a glutamine in TM1 and the prototypic set of additional coordinating groups in TM3′ and TM4′. A close-up view of the structure of these two binding sites, derived from simulations of a homology model of the M. ruminantium c ring is shown in Fig. 9 (A and B) (see also supplemental Fig. S3).

FIGURE 9.

Ion selectivity of the c ring from P. furiosus and other representative cases. A and B, close-up views of the two Na+-binding sites in a model of a c3 construct from the M. ruminantium ATP synthase. One is flanked by TM4 and TM2 within a single c subunit, and the second is formed in between adjacent c subunits in the context of the ring. Residues involved in ion coordination are highlighted. C, ion selectivity scale of representative c ring rotors, relative to the c ring from the E. hirae ATPase, including those from P. furiosus and M. ruminantium. The data derive from free energy calculations based on all-atom molecular dynamics simulations of complete c rings (E. hirae (E.h.), P. furiosus (P.f.), and S. platensis (S.p.)) or c3/4 constructs (M. ruminantium (M.r.), M. acetivorans (M.a.), and B. pseudofirmus (B.p.) OF4) in phospholipid membranes.

The Rings of E. hirae, P. furiosus, and M. ruminantium Have Equivalent Na+ Specificity

Although most ATP synthases are driven by transmembrane gradients of either protons or Na+, recent studies of the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans have revealed that its c ring is coupled to both gradients, i.e., its c subunit is effectively nonspecific under typical in vivo concentrations of H+ and Na+ (52). This is to say that the ion-binding sites in the M. acetivorans c ring are sufficiently H+ selective to counter the large physiological excess of Na+ over H+, but not so much as to preclude Na+ binding altogether. Because methanogenesis in this cytochrome-containing organism is coupled to primary Na+ and H+ translocation, the ability of M. acetivorans ATP synthase to use both seems to be a very efficient bioenergetic adaptation. However, the generality of this solution is unclear. It has been suggested that the c ring from M. ruminantium might also be able to utilize both gradients (53), but this methanogen does not have cytochromes and therefore does not have a primary proton but only a Na+ gradient generated by the methyltetrahydromethanopterin-coenzyme M methyltransferase, and thus its ATP synthase should be Na+-specific.

To clarify this question, we used molecular dynamics simulations to compute the free energy of selectivity for H+ over Na+ of the binding sites in the c rings of P. furiosus and M. ruminantium, relative to the selectivity of the c ring of the Na+-pumping ATPase from E. hirae (Fig. 9C). From this analysis, we conclude that the ion specificity of the c rings in these three species is largely identical, consistent with the similarity in the amino acid make-up of their ion-binding sites. That is, the M. ruminantium ATP synthase is very likely to be coupled exclusively by Na+ under in vivo conditions. The H+ selectivity of the M. acetivorans c ring is, by contrast, much more pronounced. As mentioned, this enables this ATP synthase to utilize the proton gradient even under conditions of Na+ excess. Organisms such as the cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis and the alkaliphilic bacterium Bacillus pseudofirmus have c rings with an even greater H+ selectivity (43, 54), so much so that Na+ binding is no longer viable, despite its excess, and therefore these ATP synthases are exclusively coupled to H+.

DISCUSSION

Archaea not only inhabit environments with extreme temperatures, pH, and/or salinity, but some can also live autotrophically. They are believed to be early life forms (55), implying that also their bioenergetics is ancient. Methanogenesis (and acetogenesis), processes in which carbon dioxide is reduced to acetyl-CoA via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, are seen as ancient pathways in which carbon dioxide formation is coupled to the synthesis of ATP via a transmembrane sodium ion gradient (56). In the simplest methanogens that do not contain cytochromes, the sodium-motive methyltetrahydromethanopterin-coenzyme M methyltransferase is the only energetic coupling site, and the ΔμNa+ established the only driving force for ATP synthesis (57, 58). This is consistent with our view that the ATP synthase from M. ruminatium is highly Na+-specific under in vivo conditions (because it is only weakly H+ selective). With the advent of additional proton bioenergetics in methanogens because of the evolution of methanophenazine and cytochromes (59), the advantages of evolving an ATP synthase that can couple to both Na+ and H+ gradients arose. As exemplified in M. acetivorans, its ATP synthase is concurrently driven by Na+ and H+ (52).

In contrast to the autotrophic methanogens, P. furiosus is heterotrophic and grows by fermentation. However, glycolysis is coupled to the reduction of the low potential electron carrier ferredoxin (E0′ = −480 mV) (60). Oxidation of reduced ferredoxin with subsequent reduction of protons to hydrogen gas was experimentally shown to be coupled to the generation of a transmembrane electrochemical ion gradient able to drive the synthesis of ATP (20). The nature of the ion translocated has not been determined yet, but it was assumed to be H+. However, in light of the finding that its ATP synthase is Na+-dependent, the gradient energizing the membrane ought to be of Na+. Anyway, this experiment clearly demonstrated that the enzyme is capable of ATP synthesis.

Here we have demonstrated that the rotor subunit c of P. furiosus is indeed a protein with four transmembrane helices but only one ion-binding site. Therefore, the solution to the enigma of how this enzyme synthesizes ATP is neither a post-transcriptional/post-translational modification of the mature c subunit, nor the presence of an unexpected second ion-binding site. The explanation may be the number of c subunits in the c ring, which LILBID-MS and EM data indicate to be 10 (7). If this interpretation was correct, the V1VO ATPase of E. hirae with its 10 c subunits in the ring should also be able to synthesize ATP. An additional piece that could contribute to the solution of the enigma is a lower phosphorylation potential in these archaea. Indeed, calculation of the ΔGp in Methanothrix soehngenii based on measurement of the nucleotides revealed a value of 45 kJ/mol for ΔGp (61). Indeed, this would drop the number of ions required for ATP synthesis from 3.4 at 60 kJ/mol down to 2.5.

The data presented here are not only consistent with our previous hypothesis that the A1AO ATP synthase of P. furiosus is Na+-motive (21) but also predict the presence of V-type Na+-dependent c subunits in a number of archaea. Only in methanogens are two ion-binding sites found in the four transmembrane helices of subunit c. This most likely reflects their autotrophic life style at the thermodynamic limit of life. The other archaea with V-type c subunits are metabolically more versatile, and the prominent function of the enzyme may be that of an ATP-driven ion pump. In P. furiosus, for example, the amount of ATP synthesized by chemiosmosis is probably much less than that by substrate level phosphorylation linked to sugar degradation. Thus, in vivo, such a c ring may be an adaptation to growth at thermodynamic equilibrium.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Thomm and Harald Huber (University of Regensburg) for supplying cells of P. furiosus.

This work was supported by Grants SFB807 (to V. M.) and EXC115 (to J. D. F.-G.) from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- DCCD

- N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide

- FEP

- free energy perturbation

- CHES

- 2-(cyclohexylamino)ethanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schäfer G., Meyering-Vos M. (1992) F-Type or V-Type? The chimeric nature of the archaebacterial ATP synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1101, 232–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Müller V., Grüber G. (2003) ATP synthases. Structure, function and evolution of unique energy converters. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60, 474–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cross R. L., Müller V. (2004) The evolution of A-, F-, and V-type ATP synthases and ATPases. Reversals in function and changes in the H+/ATP stoichiometry. FEBS Lett. 576, 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forgac M. (2007) Vacuolar ATPases. Rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 917–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grüber G., Marshansky V. (2008) New insights into structure-function relationships between archeal ATP synthase (A1AO) and vacuolar type ATPase (V1VO). Bioessays 30, 1096–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grüber G., Wieczorek H., Harvey W. R., Müller V. (2001) Structure-function relationships of A-, F- and V-ATPases. J. Exp. Biol. 204, 2597–2605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vonck J., Pisa K. Y., Morgner N., Brutschy B., Müller V. (2009) Three-dimensional structure of A1AO ATP synthase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus by electron microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10110–10119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meier T., Polzer P., Diederichs K., Welte W., Dimroth P. (2005) Structure of the rotor ring of F-Type Na+-ATPase from. Ilyobacter tartaricus. Science 308, 659–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Müller V., Lemker T., Lingl A., Weidner C., Coskun U., Grüber G. (2005) Bioenergetics of archaea. ATP synthesis under harsh environmental conditions. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 10, 167–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Müller V. (2004) An exceptional variability in the motor of archaeal A1AO ATPases. From multimeric to monomeric rotors comprising 6–13 ion-binding sites. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 36, 115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mandel M., Moriyama Y., Hulmes J. D., Pan Y. C., Nelson H., Nelson N. (1988) cDNA sequence encoding the 16-kDa proteolipid of chromaffin granules implies gene duplication in the evolution of H+-ATPases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 5521–5524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ruppert C., Schmid R., Hedderich R., Müller V. (2001) Selective extraction of subunit D of the Na+-translocating methyltransferase and subunit c of the A1AO ATPase from the cytoplasmic membrane of methanogenic archaea by chloroform/methanol and characterization of subunit c of Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus as a 16-kDa proteolipid. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 195, 47–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fricke W. F., Seedorf H., Henne A., Krüer M., Liesegang H., Hedderich R., Gottschalk G., Thauer R. K. (2006) The genome sequence of Methanosphaera stadtmanae reveals why this human intestinal archaeon is restricted to methanol and H2 for methane formation and ATP synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 188, 642–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ruppert C., Kavermann H., Wimmers S., Schmid R., Kellermann J., Lottspeich F., Huber H., Stetter K. O., Müller V. (1999) The proteolipid of the A1AO ATP synthase from Methanococcus jannaschii has six predicted transmembrane helices but only two proton-translocating carboxyl groups. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25281–25284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Slesarev A. I., Mezhevaya K. V., Makarova K. S., Polushin N. N., Shcherbinina O. V., Shakhova V. V., Belova G. I., Aravind L., Natale D. A., Rogozin I. B., Tatusov R. L., Wolf Y. I., Stetter K. O., Malykh A. G., Koonin E. V., Kozyavkin S. A. (2002) The complete genome of hyperthermophile Methanopyrus kandleri AV19 and monophyly of archaeal methanogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 4644–4649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lolkema J. S., Boekema E. J. (2003) The A-type ATP synthase subunit K of Methanopyrus kandleri is deduced from its sequence to form a monomeric rotor comprising 13 hairpin domains. FEBS Lett. 543, 47–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lewalter K., Müller V. (2006) Bioenergetics of archaea. Ancient energy conserving mechanisms developed in the early history of life. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1757, 437–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Müller V., Lingl A., Lewalter K., Fritz M. (2005) ATP synthases with novel rotor subunits. New insights into structure, function and evolution of ATPases. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 37, 455–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Robb F. T., Maeder D. L., Brown J. R., DiRuggiero J., Stump M. D., Yeh R. K., Weiss R. B., Dunn D. M. (2001) Genomic sequence of hyperthermophile Pyrococcus furiosus. Implications for physiology and enzymology. Methods Enzymol. 330, 134–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sapra R., Bagramyan K., Adams M. W. (2003) A simple energy-conserving system. Proton reduction coupled to proton translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 7545–7550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pisa K. Y., Huber H., Thomm M., Müller V. (2007) A sodium ion-dependent A1AO ATP synthase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon. Pyrococcus furiosus. FEBS J. 274, 3928–3938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schägger H., von Jagow G. (1987) Tricine-sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166, 368–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shevchenko A., Wilm M., Vorm O., Mann M. (1996) Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68, 850–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buschmann S., Warkentin E., Xie H., Langer J. D., Ermler U., Michel H. (2010) The structure of cbb3 cytochrome oxidase provides insights into proton pumping. Science 329, 327–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Henikoff S., Henikoff J. G. (1992) Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 10915–10919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li W., Jaroszewski L., Godzik A. (2001) Clustering of highly homologous sequences to reduce the size of large protein databases. Bioinformatics 17, 282–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li W., Jaroszewski L., Godzik A. (2002) Tolerating some redundancy significantly speeds up clustering of large protein databases. Bioinformatics 18, 77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Notredame C., Higgins D. G., Heringa J. (2000) T-Coffee. A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 302, 205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murata T., Yamato I., Kakinuma Y., Leslie A. G., Walker J. E. (2005) Structure of the rotor of the V-Type Na+-ATPase from Enterococcus hirae. Science 308, 654–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Melo F., Sali A. (2007) Fold assessment for comparative protein structure modeling. Protein Sci. 16, 2412–2426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shen M. Y., Sali A. (2006) Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures. Protein Sci. 15, 2507–2524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones D. T. (1999) Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 292, 195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bernsel A., Viklund H., Hennerdal A., Elofsson A. (2009) TOPCONS. Consensus prediction of membrane protein topology. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W465–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kabsch W., Sander C. (1983) Dictionary of protein secondary structure. Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22, 2577–2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lomize M. A., Lomize A. L., Pogozheva I. D., Mosberg H. I. (2006) OPM. Orientations of proteins in membranes database. Bioinformatics 22, 623–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Staritzbichler R., Anselmi C., Forrest L. R., Faraldo-Gómez J. D. (2011) GRIFFIN. A versatile methodology for optimization of protein-lipid interfaces for membrane protein simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comp. 7, 1167–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Phillips J. C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R. D., Kalé L., Schulten K. (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. MacKerell A. D., Bashford D., Bellott M., Dunbrack R. L., Evanseck J. D., Field M. J., Fischer S., Gao J., Guo H., Ha S., Joseph-McCarthy D., Kuchnir L., Kuczera K., Lau F. T., Mattos C., Michnick S., Ngo T., Nguyen D. T., Prodhom B., Reiher W. E., Roux B., Schlenkrich M., Smith J. C., Stote R., Straub J., Watanabe M., Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J., Yin D., Karplus M. (1998) All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 102, 3586–3616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mackerell A. D., Jr., Feig M., Brooks C. L., 3rd (2004) Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields. Limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1400–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fillingame R. H. (1976) Purification of the carbodiimide-reactive protein component of the ATP energy-transducing system of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 251, 6630–6637 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Altendorf K. (1977) Purification of the DCCD-reactive protein of the energy-transducing adenosine triphosphatase complex from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 73, 271–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Leone V., Krah A., Faraldo-Gómez J. D. (2010) On the question of hydronium binding to ATP synthase membrane rotors. Biophys. J. 99, L53-L55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pogoryelov D., Yildiz O., Faraldo-Gómez J. D., Meier T. (2009) High-resolution structure of the rotor ring of a proton-dependent ATP synthase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 1068–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Furutani Y., Murata T., Kandori H. (2011) Sodium or lithium ion-binding-induced structural changes in the K-ring of V-ATPase from Enterococcus hirae revealed by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 2860–2863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kluge C., Dimroth P. (1993) Specific protection by Na+ or Li+ of the F1FO-ATPase of Propionigenium modestum from the reaction with dicyclohexylcarbodiimide. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 14557–14560 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Spruth M., Reidlinger J., Müller V. (1995) Sodium ion dependence of inhibition of the Na+-translocating F1FO-ATPase from Acetobacterium woodii. Probing the site(s) involved in ion transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1229, 96–102 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Murata T., Kawano M., Igarashi K., Yamato I., Kakinuma Y. (2001) Catalytic properties of Na+-translocating V-ATPase in Enterococcus hirae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1505, 75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Meier T., Krah A., Bond P. J., Pogoryelov D., Diederichs K., Faraldo-Gómez J. D. (2009) Complete ion-coordination structure in the rotor ring of Na+-dependent F-ATP synthases. J. Mol. Biol. 391, 498–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pogoryelov D., Krah A., Langer J. D., Yildiz Ö., Faraldo-Gómez J. D., Meier T. (2010) Microscopic rotary mechanism of ion translocation in the FO complex of ATP synthases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 891–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mizutani K., Yamamoto M., Suzuki K., Yamato I., Kakinuma Y., Shirouzu M., Walker J. E., Yokoyama S., Iwata S., Murata T. (2011) Structure of the rotor ring modified with N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide of the Na+-transporting vacuolar ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 13474–13479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schlegel K., Leone V., Faraldo-Gómez J. D., Müller V. (2012) Promiscuous archaeal ATP synthase concurrently coupled to Na+ and H+ translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 947–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McMillan D. G., Ferguson S. A., Dey D., Schröder K., Aung H. L., Carbone V., Attwood G. T., Ronimus R. S., Meier T., Janssen P. H., Cook G. M. (2011) A1AO-ATP synthase of Methanobrevibacter ruminantium couples sodium ions for ATP synthesis under physiological conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 39882–39892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Krah A., Pogoryelov D., Langer J. D., Bond P. J., Meier T., Faraldo-Gómez J. D. (2010) Structural and energetic basis for H+ versus Na+ binding selectivity in ATP synthase FO rotors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1797, 763–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stetter K. O. (2006) History of discovery of the first hyperthermophiles. Extremophiles 10, 357–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Poehlein A., Schmidt S., Kaster A. K., Goenrich M., Vollmers J., Thürmer A., Bertsch J., Schuchmann K., Voigt B., Hecker M., Daniel R., Thauer R. K., Gottschalk G., Müller V. (2012) An ancient pathway combining carbon dioxide fixation with the generation and utilization of a sodium ion gradient for ATP synthesis. PLoS One 7, e33439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gottschalk G., Thauer R. K. (2001) The Na+-translocating methyltransferase complex from methanogenic archaea. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1505, 28–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thauer R. K., Kaster A. K., Seedorf H., Buckel W., Hedderich R. (2008) Methanogenic archaea. Ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Deppenmeier U. (2002) Redox-driven proton translocation in methanogenic archaea. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59, 1513–1533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schut G. J., Boyd E. S., Peters J. W., Adams M. W. (2012) The modular respiratory complexes involved in hydrogen and sulfur metabolism by heterotrophic hyperthermophilic archaea and their evolutionary implications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jetten M. S., Stams A. J., Zehnder A. J. (1991) Adenine nucleotide content and energy charge of Methanothrix soehngenii during acetate degradation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 84, 313–317 [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bradford M. M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.