Background: VirB4 ATPases are involved in protein transport in T4SS.

Results: The structure of the conjugative VirB4 homologue TrwK has been determined by single-particle electron microscopy.

Conclusion: TrwK forms hexamers and binds preferentially G4-quadruplex DNA as the coupling protein TrwB.

Significance: The results provide structural and biochemical evidence for a common evolutionary scenario between DNA and protein translocases.

Keywords: ATPases, Bacterial Conjugation, Electron Microscopy (EM), Secretion, Structural Biology

Abstract

VirB4 proteins are ATPases essential for pilus biogenesis and protein transport in type IV secretion systems. These proteins contain a motor domain that shares structural similarities with the motor domains of DNA translocases, such as the VirD4/TrwB conjugative coupling proteins and the chromosome segregation pump FtsK. Here, we report the three-dimensional structure of full-length TrwK, the VirB4 homologue in the conjugative plasmid R388, determined by single-particle electron microscopy. The structure consists of a hexameric double ring with a barrel-shaped structure. The C-terminal half of VirB4 proteins shares a striking structural similarity with the DNA translocase TrwB. Docking the atomic coordinates of the crystal structures of TrwB and FtsK into the EM map revealed a better fit for FtsK. Interestingly, we have found that like TrwB, TrwK is able to bind DNA with a higher affinity for G4 quadruplex structures than for single-stranded DNA. Furthermore, TrwK exerts a dominant negative effect on the ATPase activity of TrwB, which reflects an interaction between the two proteins. Our studies provide new insights into the structure-function relationship and the evolution of these DNA and protein translocases.

Introduction

Type IV secretion systems (T4SS)3 mediate the exchange of genetic material in bacterial conjugation and the delivery of virulence effectors into eukaryotic cells (1). Conjugative T4SS are essential for the widespread dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes among pathogenic bacteria (2). T4SS consist of large macromolecular assemblies formed by 11 different proteins (VirB1 to VirB11 in the nomenclature of Agrobacterium tumefaciens) (3) and a coupling protein, VirD4, involved in ssDNA transport among cells. Three of these proteins, VirB4, VirB11, and VirD4, are ATPases that provide the energy for pilus assembly and DNA/protein transport (4–8).

VirB4 proteins are the most conserved component of T4S systems (9), and they are essential for plasmid transfer and virulence (10). The proposed biological function of VirB4 proteins is to mediate pilin dislocation from the inner membrane (11), thus promoting pilus assembly, but they have also been proposed to play a direct role in the transfer of substrates to the membrane translocase complex (12).

VirB4 proteins are large proteins with two clear distinct domains: a well conserved C-terminal domain (CTD), containing the Walker A and Walker B motifs, and a less conserved N-terminal domain (NTD) which, depending on the species, could contain predicted transmembrane spans (7, 13). On the basis of computer predictions, molecular models of the CTD have been proposed (14, 15). These models have been built using the structure of TrwB, the coupling protein of conjugative R388, as a template. TrwB is a DNA-dependent hexameric ATPase (4, 16) that couples the relaxosome processing machinery toward the translocating complex (17). TrwB structure (18) is related to other hexameric helicases, F1-ATPases and FtsK, a DNA translocase involved in bacterial division. Comparative genomic analysis revealed that VirB4, VirD4/TrwB, and FtsK/SpoIIIE proteins are closely related (19). Despite the variability in size and biological functions, all of them contain a motor domain that seems to have evolved from a common evolutionary ancestor (20). This ring-shaped motor domain converts the energy of ATP hydrolysis into mechanical work, facilitating the wide variety of functions carried out by this family of proteins.

The structure of the VirB4 CTD from Thermoanaerobacter pseudethanolicus has been obtained recently (21). The structure is very similar to the computer-generated models on the basis of TrwB (14, 15). A negative stain model of a complex formed by a VirB4 monomer bound to the core subunits VirB7/VirB9/VirB10 of plasmid pKM101 has also been reported (21). However, in these structures, the VirB4 NTD cannot be distinguished clearly. The structure of the VirB4 CTD has been obtained in its monomeric form, but dimeric and hexameric forms of the protein have also been reported (7, 8, 22). Here, we have obtained the first structure of full-length TrwK, the VirB4 homologue in conjugative R388, by single-molecule electron microscopy. The structure consists of a hexameric double ring forming a barrel-shaped structure. The two hexameric rings are different in size, corresponding to the N-terminal and C-terminal ends of the protein, as determined by gold labeling electron microscopy. Docking the crystal structures of TrwB and FtsK on the EM map revealed a better fit for FtsK.

TrwB and FtsK both act as DNA pumps. We wondered whether the structural similarity with VirB4 proteins would be accompanied by similar biochemical functions. We were intrigued by recent findings showing the ability of two VirB4 homologues to bind DNA (8, 23). In this work, we show that TrwK is also able to bind DNA, but, even more surprisingly, we found that the affinity of TrwK for G4 quadruplex DNA was much higher than for single-stranded DNA, similar to what has been observed for TrwB (23). Furthermore, we have found that the DNA-dependent activity by TrwB is inhibited by TrwK, which demonstrates a direct interaction between these proteins. These results are in accordance with recent studies on PrgJ, the VirB4 homologue in Enterococcus faecalis pCF10 system (23).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning, Protein Expression, and Purification

TrwK, TrwBΔN70, and TrwBΔN70 (W216A) were cloned, overproduced in the Escherichia coli C41(DE3) strain (24), and purified as described previously (4, 7). Fractions used for EM were eluted from a Superdex200 GL 3.2/30 column in a buffer consisting of 50 mm PIPES-NaOH (pH 6.45), 75 mm potassium acetate, 5% (w/v) glycerol, 10 mm magnesium acetate, 0.1 mm EDTA, and 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride.

ATP Hydrolysis Assays

ATPase activities by TrwK and TrwBΔN70 were measured by a coupled enzyme assay (25) as described previously (4, 7). For inhibition assays, mixtures of proteins were incubated for 5 min and then added to the ATP assay buffer as described in Ref. 15.

DNA Binding Assays

TrwK DNA binding activity was measured by gel shift assays. G4 DNA and ssDNA substrates were prepared, and 5′-radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP as described previously (16). TrwBΔN70 and TrwK were added to the binding buffer (16), and, after incubation at 37 °C for 10 min, reaction mixtures were loaded onto a 10% native PAGE gel (1× Tris-borate-EDTA). Gels were analyzed using a Molecular Imager FX ProSystem (Bio-Rad). For quantification, the intensity of bands corresponding to free DNA and TrwK-DNA complexes was determined using ImageQuant software.

Electron Microscopy and Image Analysis

Aliquots of TrwK (0.1 mg/ml) were applied onto freshly glow-discharged carbon-coated grids. Samples were negatively stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate. Electron micrographs were recorded at ×60,000 nominal magnification on Kodak SO-163 film using a JEOL 1200EX-II electron microscope operated at 100 kV. The micrographs were digitized in a Zeiss SCAI scanner with a final sampling rate of 4.66 Å/pixel. The defocus and astigmatism of the images were determined with CTFFIND3 (26), and phases were corrected for the contrast transfer function effect. A total of 4548 particles were selected manually and normalized using XMIPP image processing software (27). The alignment and classification were performed by maximum likelihood multireference refinement methods (28). A neural network self-organizing map was used as the main classification tool (29) to analyze the variability of the images, resulting in a final data set of 1179 particles. A rotational spectrum was done as defined in Ref. 30. Reference models and first refinements steps during three-dimensional reconstruction were performed using the EMAN software package (31) until a volume with the general shape of the complex became evident. The XMIPP software package (27) was used in the subsequent iterative angular refinement procedure.

Gold Labeling

His-tagged TrwK was incubated for 30 min with Ni-NTA-conjugated 5-nm gold (Nanoprobes, NY) at a 1:10 TrwK hexamer:Ni-gold molar ratio. Samples were applied onto freshly glow-discharged carbon-coated grids and negatively stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate. Electron micrographs were recorded at ×150,000 nominal magnification on a camera GATAN model ORIUS SC 1000 CCD using a JEOL JEM-1011 electron microscope operated at 80 kV with a final sampling rate of 6.4 Å/pixel.

Docking of Atomic Models into the EM Map

Atomic coordinates of monomeric VirB4 CTD (PDB code 4AG5) (21), hexameric TrwBΔN70 (PDB code 1E9R) (18), and FtsK of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PDB code 2IUU) (32) were fitted with UCSF Chimera (33) into the TrwK EM volume, previously filtered to 22-Å resolution. Docking was further optimized with colacor (cross-correlation-based low resolution rigid-body refinement of molecular dockings), which is part of the Situs program package (34). Hexameric VirB4 was constructed by aligning each monomer of the VirB4 CTD to the hexameric structure of FtsK. For fitting of volumes, atomic structures were filtered to 20-Å resolution and then fitted into the EM map with UCSF Chimera. In the case of Pa-FtsK, the handle loop (comprising residues 570–582) was not included in the volume, as TrwK does not share any sequence similarity with FtsK in this region.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Protein sequences were retrieved from Uniprot, aligned, and clustered as described previously (20). Clusters corresponding to FtsK/SpoIIIE, VirD4/TraD, and VirB4 members were selected to generate a library of 1072 sequences. Unpredicted, uncharacterized, and putative sequences were removed from this library (669 sequences). Then a database was created including sequences of the best known members (mainly those annotated in the Swiss-Prot database or those characterized genetically or biochemically). The sequences of Pa-FtsK, TrwB, and VirB4, for which x-ray structure information is available, were used to identify the motor domains of these proteins. Then the motor domain sequences were aligned with T-coffee (35). Phylogenetic analysis was performed with FastTree using default settings (36). Tree representations were carried out using Archaeopteryx (37). For rooting purposes, four RecA sequences (E. coli, Thermotoga maritima, P. aeruginosa, and Ureaplasma urealyticum) were selected and included in the analysis.

RESULTS

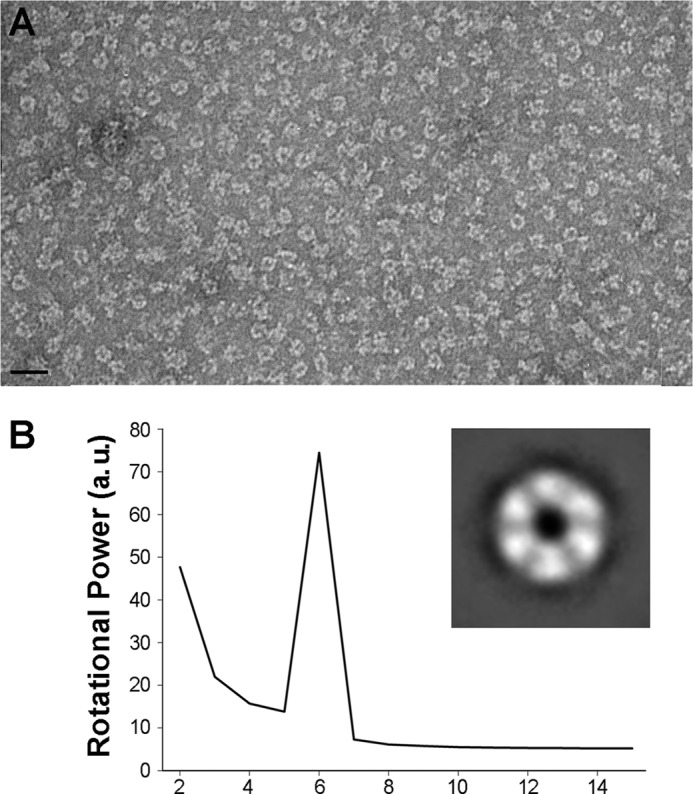

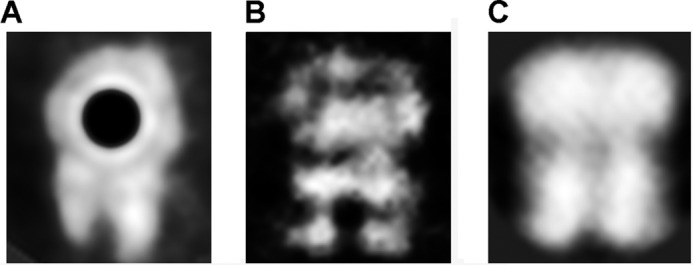

Three-dimensional Reconstruction of TrwK

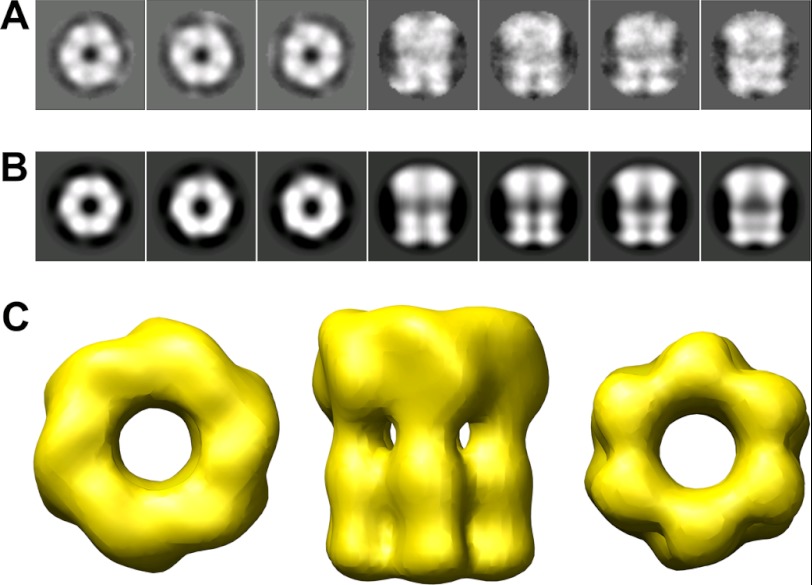

Purified TrwK, eluted from a gel filtration column at a molecular weight compatible with a hexamer, was analyzed by EM. Negatively stained specimens showed a widespread of individual particles with a ring-shaped structure (Fig. 1A). In addition, dumbbell-shaped particles were also observed and were interpreted as side views of the analyzed specimen. Images were subjected to reference-free classification to align and average similar views. Rotational symmetry analysis of the rings clearly identified a 6-fold symmetry along the z axis (Fig. 1B). As the size and shape of the rings was not uniform, possibly reflecting top and bottom views, C6 symmetry was applied in the following three-dimensional reconstruction. Unbiased class averages (Fig. 2A) were matched by projections of the final volume (Fig. 2B), supporting the correctness of the reconstruction. The three-dimensional reconstruction revealed a structure consisting of a double hexameric ring (Fig. 2C). The dimensions of the final reconstruction were 165 Å along the large axis with an inner diameter of 42 Å and outer diameters of 132 Å and 124 Å for the top and bottom ends, respectively. To discriminate which of these ends corresponded to the N- and C- terminal halves of the protein, TrwK was cloned with a His tag in the N terminus and labeled with Ni-NTA-conjugated gold. Image analysis of the gold-labeled particles (Fig. 3) allowed us to clearly identify the top end as the N terminus of the protein.

FIGURE 1.

EM of TrwKwt of conjugative plasmid R388 in its hexameric form. A, TrwK was negatively stained with uranyl acetate and analyzed by EM. Scale bar = 30 nm. B, rotational power analysis of TrwK rings class averages (inset) with harmonic energy percentage as a function of the radius. a.u., arbitrary units.

FIGURE 2.

3D reconstruction of TrwK of conjugative plasmid R388. Class averages of TrwK (A) and matching projections of the final volume (B). C, final volume obtained by projection matching and angle refinement and low-passed filtered to 22 Å. Top (left panel), side (center panel), and bottom (right panel) views of the volume. The top and bottom views, corresponding to the N-terminal and C-terminal ends of the protein, respectively, differ in size (132 Å and 124 Å, respectively), and the longitudinal dimension is 165 Å.

FIGURE 3.

Gold labeling electron microscopy. His-tagged TrwK was incubated with Ni-NTA-conjugated gold (5 nm), negatively stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate, and analyzed by electron microscopy. Class averages of gold-labeled TrwK (A), comparison with unlabeled TrwK (B), and projection images of the 3D reconstruction (C).

Phylogenetic Relationship between TrwK and TrwB/FtsK DNA Translocases

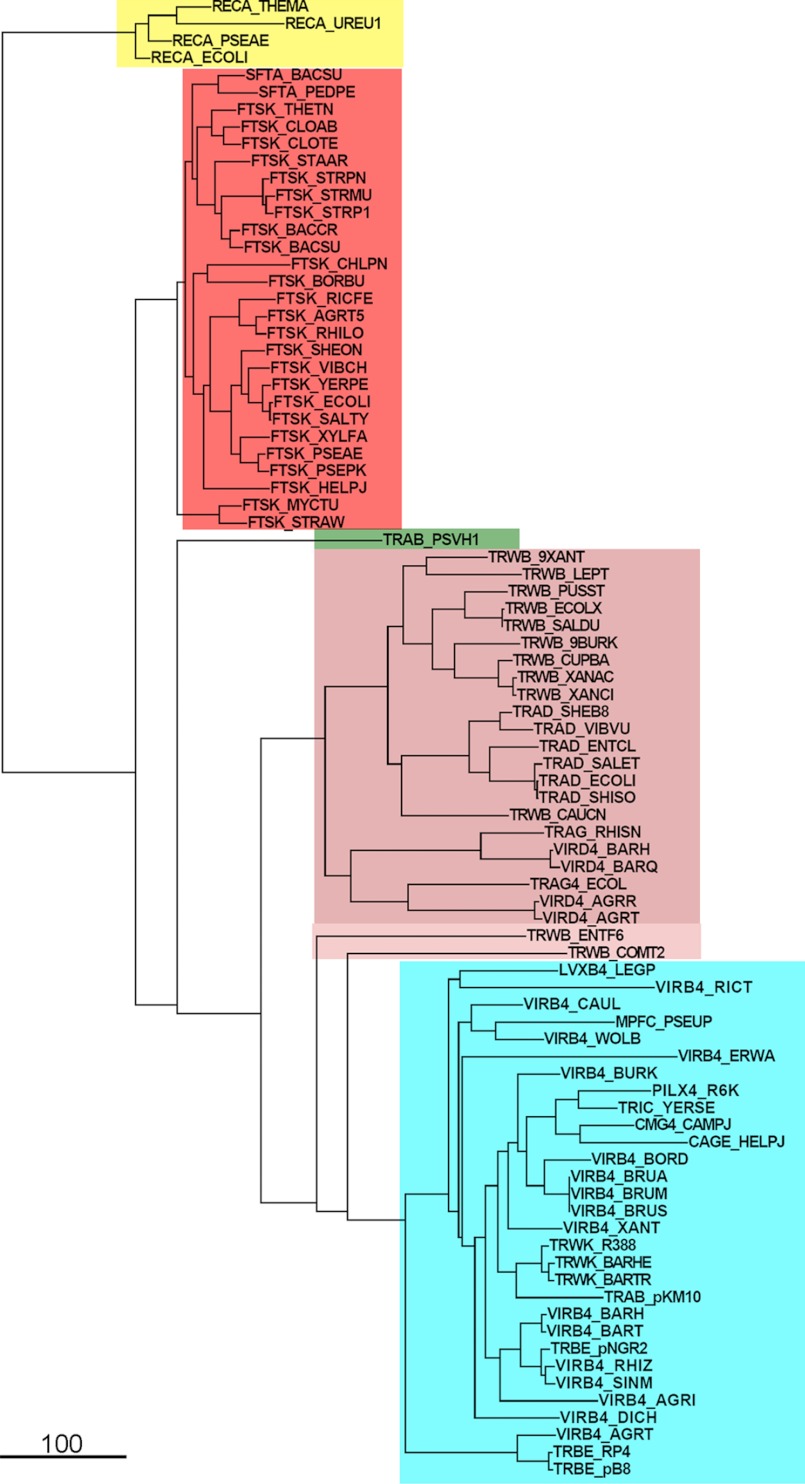

VirB4 proteins belong to a family of P-loop ATPases that also includes FtsK/SpoIIIE and their archaea relatives HerA and VirD4/TrwB-like proteins (19). These proteins contain a motor domain that is well conserved, suggesting an evolutionary common ancestor (20). However, the N-terminal halves of FtsK/SpoIIIE and VirB4 proteins are not that well conserved, and the size and sequence of these N termini are variable. Here, we have selected sequences corresponding to the motor domain of FtsK/SpoIIIE, SftA, a FtsK homologue in Bacillus subtilis, VirB4, and TrwK-like relatives and VirD4/TraD/TrwB coupling proteins. We also included TraB, a conjugal double-stranded DNA transfer protein in Streptomyces that resembles FtsK (38). The phylogenetic analysis was performed in the presence of four RecA proteins that were used to root the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4). The results suggest that the motor domain of FtsK-like proteins diverged separately from that of VirD4 and VirB4 proteins. Interestingly, we found that the conjugative dsDNA translocase TraB of Streptomyces venezolae pSHV1 plasmid (Fig. 4, dark olive) seems to have diverged from the coupling proteins before the speciation between VirD4 and VirB4 proteins and after the diversification between FtsK and VirB4-VirD4 families.

FIGURE 4.

Phylogenetic tree of the motor domain of FsK/SpoIIIE- VirD4/TrwB- and VirB4-like proteins. Protein sequences were retrieved from Uniprot and clustered as described in Ref. 20. Sequences corresponding to the motor domain of these proteins were selected and aligned with T-coffee (35). Phylogenetic trees were built with FastTree (36) and represented with Archeopteryx (37). The tree was rooted with RecA sequences (yellow). FtsK/SpoIIIE, VirD4/TrwB, and VirB4 clades are colored in red, salmon, and cyan, respectively. TraB, the conjugative dsDNA transfer protein in Streptomyces, is shown in dark olive.

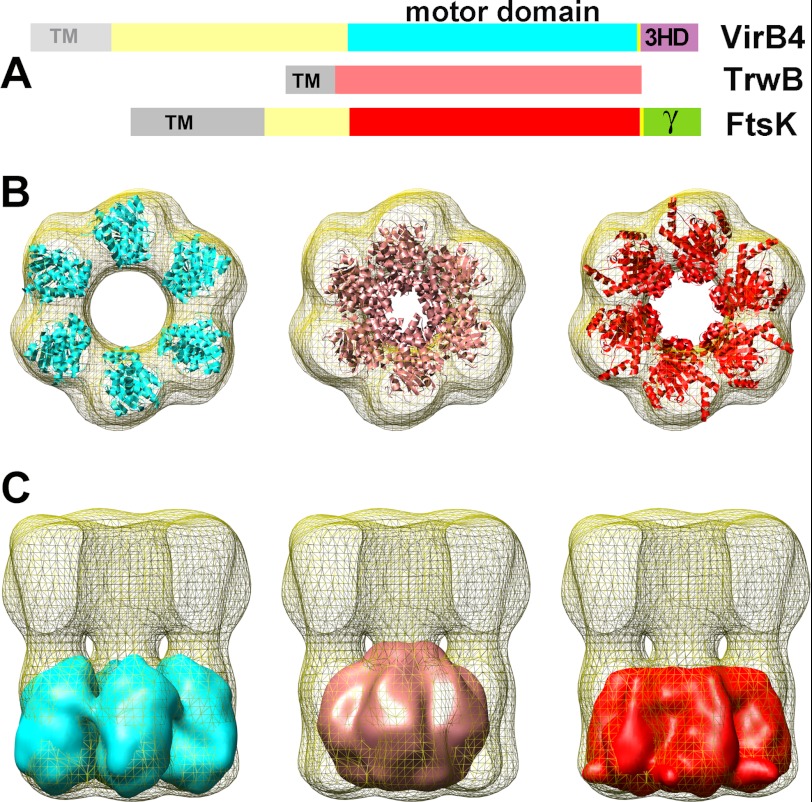

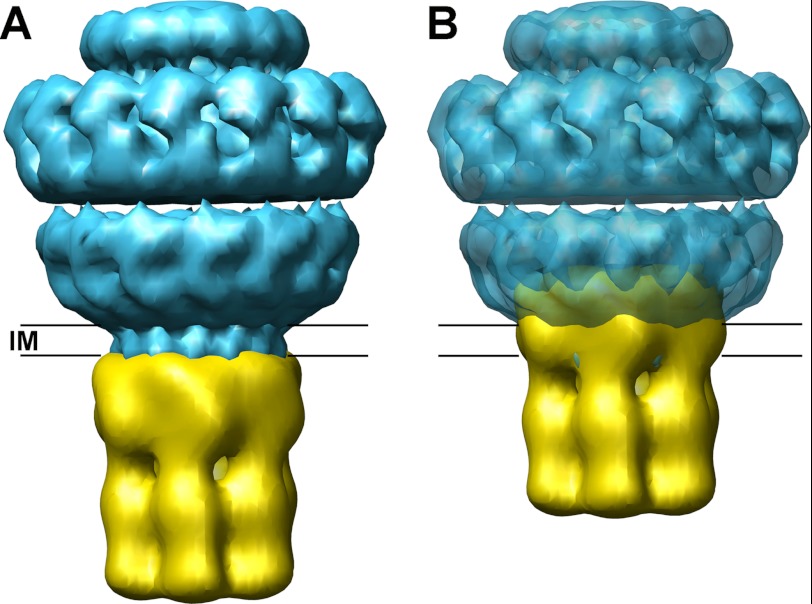

Fitting of Atomic Coordinates into the EM Map

On the basis of the evolutionary relationship between the motor domains of FtsK, TrwB, and TrwK, we decided to dock the atomic structures of hexameric TrwBΔN70 (PDB code 1E9R) (18) and FtsKCTD (PDB code 2IUU) (32) into the EM map. Interestingly, FtsK fits much better than TrwB (the off-lattice Powell cross-correlation values were 73 and 61%, respectively). The dimensions of the inner channel of FtsK (31 Å) were closer to the EM inner diameter volume (42 Å) than the hexameric TrwB (8 Å) (Fig. 5B). Therefore, to fit the atomic coordinates of VirB4CTD from T. pseudethanolicus (PDB code 4AG5) (21) into the EM map, each monomer was aligned using hexameric FtsK as a template. The resulting hexameric VirB4CTD model was fitted into the EM map in the same way as the TrwBΔN70 and FtsKCTD hexameric crystal structures (Fig. 5B). Similar to VirB4CTD, a hexameric model of TrwKCTD was created by aligning the computer-generated model of TrwKCTD (15) to FtsK. The hexamer was fitted into the EM map, showing no differences. In addition, the atomic structures of hexameric TrwKCTD, VirB4CTD, TrwBΔN70, and FtsKCTD were filtered to 20 Å and docked into the EM map (Fig. 5C). The volumes adjusted very well into the EM map, occupying roughly 40% of the density, as expected. Considering the size of the CTD of these proteins (TrwK is 823 residues in length, only 359 residues per monomer form part of the C-terminal structure, and the crystal structure of FtsK only comprises 406 residues), these results further support the accuracy of the EM volume.

FIGURE 5.

Fitting atomic coordinates of TrwB and FtsK into TrwK EM map. A, schematic representation of the VirB4 homologue in H. pylori, the coupling protein TrwB of plasmid R388, and P. aeruginosa FtsK. The transmembrane domains (TM) are depicted in gray. TrwK of plasmid R388, as well as many other VirB4 homologues, lacks the transmembrane domain, thus the light gray color. The motor domains in TrwK, TrwB, and FtsK are colored in cyan, salmon, and red, respectively. B, the hexameric atomic structures obtained by x-ray crystallography of TrwBΔN70 (PDB code 1E9R) (salmon) and the C-terminal half of P. aeruginosa FtsK (PDB code 2IUU) were docked into the 3D EM map of TrwK. The atomic model of the monomeric Tps VirB4CTD was previously aligned to FtsK into the EM model. The resulting VirB4CTD hexamer (cyan) was finally fitted into the EM map as above. C, the atomic structures of TrwBΔN70, FtsKCTD, and the model of VirB4CTD were filtered to 20 Å resolution and docked into the EM map of TrwK.

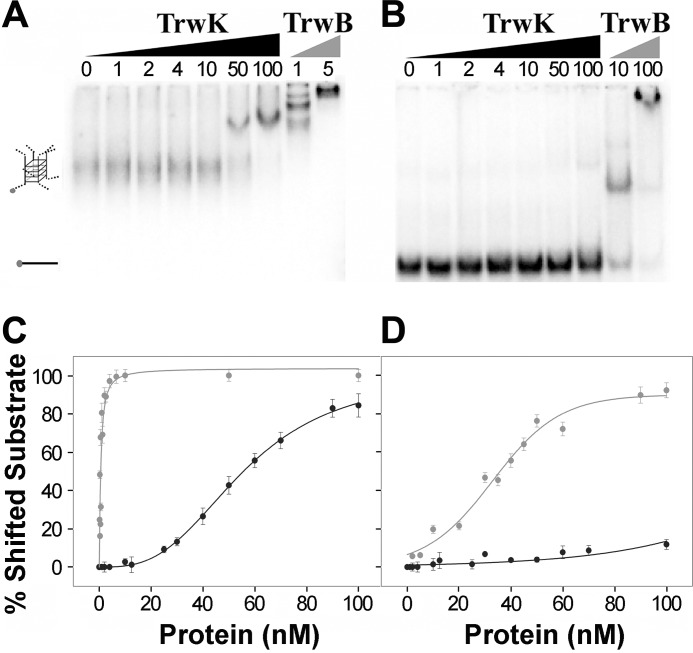

TrwK Displays a Higher Affinity for G-quadruplex DNA Structures over ssDNA

PrgJ, a VirB4 homologue in plasmid pCF10 from E. faecalis, has been recently shown to bind single- and double-stranded DNA substrates without sequence specificity (23). On the bases of the reported data and the structural similarities of TrwK with the DNA translocases TrwB and FtsK described in this work, we wondered if TrwK showed any preference for a particular DNA substrate. TrwBΔN70 has been shown to bind G4-quadruplex DNA structures with a very high affinity (Kd = 0.3 nm), 100-fold higher than the affinity for single-stranded DNA (16). These G4 DNA secondary structures are formed spontaneously in G-rich DNA sequences (39). Here we show, by DNA mobility shift assays, that TrwK is also able to bind G4 DNA, albeit with almost 200 times lower affinity than TrwB (Fig. 6). Surprisingly, and similar to TrwB, the affinity of TrwK for G4-quadruplex (Kd = 56 nm) is much higher than for single-stranded DNA (Kd > 500 nm). Therefore, we can conclude that TrwK also displays a preferential binding for G4 DNA.

FIGURE 6.

DNA mobility shifts assays of TrwK and TrwBΔN70. TrwK and TrwBΔN70 at protein concentrations in the range of 0–100 nm were mixed with 0.5 nm 32P-labeled G4 DNA (A) and ssDNA substrate (B), and the resulting nucleoprotein complexes were separated in native PAGE. The markers to the left of the gels represent G4 DNA and ssDNA (45-mer), respectively. Quantification of the gel mobility shift analysis of G4 DNA (C) and ssDNA (D) revealed that TrwK (black) binding affinity for G4 DNA (Kd = 56 nm) is about 200 times lower than TrwB (gray) (Kd = 0.3 nm) but still much higher than for ssDNA.

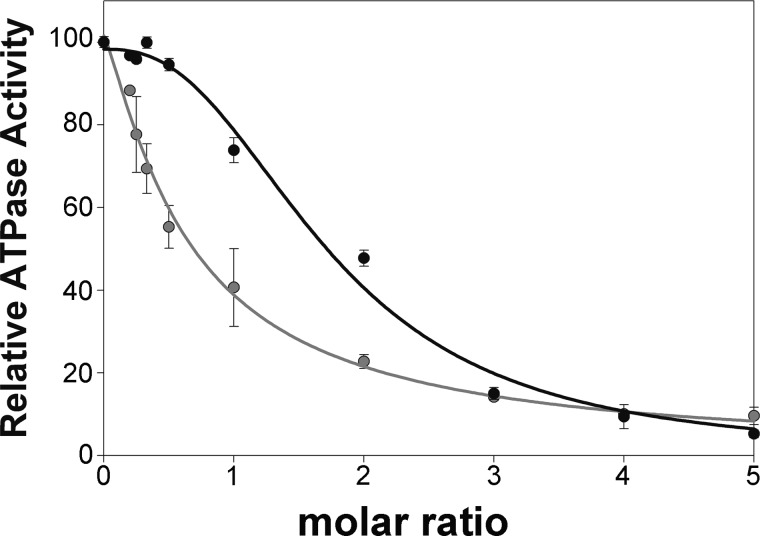

TrwK Inhibits DNA-dependent ATPase Activity by TrwB

Although TrwK is able to bind DNA, the ATPase activity by TrwK is not affected by addition of ssDNA or G4 DNA. In contrast, TrwBΔN70 displays an ATPase activity of 2000 nmols ATP min−1mg−1 in the presence of G-quadruplex DNA (16). Under the same conditions, TrwK ATPase activity is low (50 nmols ATP min−1mg−1) (7). Given the structural homology that TrwBΔN70 shares with the C-terminal half of TrwK, we wondered if an interaction between these two proteins might affect TrwBΔN70 DNA-dependent ATPase activity. Interestingly, we found that when ATPase activity was tested in the presence of both TrwBΔN70 and TrwK proteins, the activity of TrwBΔN70 was inhibited, indicating a dominant negative effect. The increase in TrwK concentration correlated with a decrease in the ATPase rate (Fig. 7). Addition of equimolar ratios of TrwBΔN70 and TrwK to the DNA-dependent ATP assay resulted in a 30% decrease of the ATPase activity. Similar ATPase rates could be obtained if only 70% of the initial concentration of TrwB would be present in the assay. These results suggest that TrwBΔN70 monomers are removed from the solution by specific interaction with TrwK, forming heterocomplexes that would be inactive. Similar non-functional heterohexamers were found upon addition of ATPase-defective mutants to DNA translocases, such as FtsK (32) or RuvB (40).

FIGURE 7.

Dominant negative effect on TrwBΔN70 ATPase activity exerted by TrwK and TrwBΔN70 (W216A). G4 DNA-dependent ATPase activity by TrwBΔN70 was measured at increasing concentrations of TrwK (black) and TrwBΔN70(W216A) mutant protein (gray). TrwBΔN70 protein concentration was fixed to 0.3 μm. Proteins were mixed and incubated for 5 min and added to the G4 DNA-containing ATP hydrolysis buffer. Relative activity is expressed as percentage ATPase rates at a constant TrwBΔN70 concentration. A value of 100% of hydrolysis corresponds to 2000 nmol ATP hydrolyzed per minute and milligram of protein.

To understand the extent of the interaction between TrwB and TrwK, we conducted a comparative study using a TrwBΔN70 mutant variant, TrwBΔN70 (W216A), shown previously to be able to inhibit the DNA-dependent TrwBN70 ATPase activity by forming inactive heterocomplexes (4). This mutant had a dominant negative effect on TrwB activity both in vitro and in vivo. Comparison between the inhibition kinetics of TrwBΔN70 ATPase activity by TrwBΔN70(W216A) and TrwK (Fig. 7) revealed that the TrwB mutant variant inhibited TrwBΔN70 ATPase activity at lower molar ratios than TrwK. Interestingly, in the case of the inhibition by TrwK, the shape of the curve suggests the existence of a marked cooperative effect, probably due to the fact that more copies of TrwK are required to appreciate initial inhibition values. Because the efficiency for hexamer formation by the TrwBΔN70(W216A) mutant was reported to be similar to the wild-type protein (4), these results reflect that TrwBΔN70 binds TrwBΔN70(W216A) with a higher affinity than TrwK, as expected.

DISCUSSION

The crystal structure of the VirB4 C-terminal domain (CTD) from T. pseudethanolicus (TpsVirB4) in its monomeric form has been published recently (21). The structure confirms that VirB4-CTD is structurally similar to TrwBΔN70 (18), as predicted previously by molecular modeling using TrwB coordinates as a template (14). However, despite efforts to obtain the structure of full-length VirB4 (21), the structural details of the NTD of the protein remain unclear. On the other hand, much discussion on the oligomeric state of VirB4 has taken place because monomeric, dimeric, trimeric, and hexameric forms of the protein have been reported (7, 8, 22). Here we have obtained, for the first time, the 3D structure of full-length TrwK in its hexameric form by single-particle electron microscopy. The structure comprises not only the CTD but also the mostly unknown NTD. Combination of this structural information with biochemical and phylogenetic analysis provides new insights on the function and evolution of VirB4 proteins.

On the basis of the structural similarity of theVirB4 C-terminal half with the coupling protein TrwB, it has been proposed that VirB4 proteins assemble as homohexamers (14). However, there are genetic and biochemical studies that suggest that the oligomeric state of VirB4 proteins is a dimer (22). Furthermore, the VirB4 homolog in plasmid pKM101 has been shown to be present both as hexamer and dimer, whereby the hexameric form is soluble and catalytically active and the dimeric form inactive and membrane-associated (8). Accordingly, a mutation in the arginine finger motif in the TpsVirB4 protein almost completely abolishes the ATPase activity of the protein (21), which indicates that the protein must oligomerize to be active. This is a common feature in all AAA+/RecA ATPases that are active as hexamers. Therefore, the 3-dimensional structure of TrwK shown here might correspond to the active form of the enzyme.

VirB4 proteins are related to DNA translocases, such as the coupling proteins VirD4/TrwB and the chromosome segregation pump FtsK (19). Phyletic distributions obtained by comparative sequence analysis of FtsK proteins with other P-loop ATPases suggest that VirB4 and VirD4 families might have derived from DNA pumps of ancestral plasmids, appearing after the primary diversification of archaea and bacteria (19). FtsK proteins, on the contrary, might have evolved from an earlier evolutionary precursor from which A32-like dsDNA viral packing ATPases have also arisen (19). In this work, we have just focused on the evolution of the motor domain of VirB4, VirD4, and FtsK proteins. The data suggest that the motor domain of FtsK-like proteins diverged separately from that of VirD4 and VirB4 proteins. In addition, we incorporated in this analysis TraB, a recently characterized dsDNA pump of a conjugal plasmid transfer in Streptomyces that has been suggested to be closely related to FtsK proteins (38). Interestingly, we found that the motor domain of TraBpSVH1 seems to have evolved from an ancestor from which VirB4 and VirD4 proteins have evolved.

Similar to FtsK, most VirB4 proteins have a long N-terminal extension that is less conserved than the ATPase-containing region. Little is known about the NTD of VirB4 proteins, but it is likely that this domain is involved in interactions with other components of the T4SS core complex. There is variability at the N-terminal end of VirB4 proteins, and there are clades within the VirB4 family that contain members with membrane spans, such as Helicobacter pylori and Yersinia pestis homologues. However, the N-terminal transmembrane domain of these VirB4 proteins has probably arisen from a fusion with the integral membrane protein VirB3. In fact, several members of the VirB4 family have VirB3 sequences already incorporated as fusion proteins (41), and in most T4SS, there is a conserved gene synteny in which virB3 gene is upstream of virB4. Surprisingly, in a recent 3D reconstruction of the T4SS core complex bound to a VirB4 monomer (21), the NTD of the protein appeared to be embedded in the periplasmic I layer of the core complex and not underneath, as would have been expected. If that were the case, it is difficult to imagine where VirB3 would be located. Furthermore, according to that structure, the linker region connecting the NTD and the CTD of VirB4 would be located in the inner membrane region of the core complex. Such a location could only be explained after a large conformational change that allows the opening of the base of the core complex. On the basis of these considerations, we propose an alternative model (Fig. 8A) in which the VirB4 hexamer would interact with the core complex on the cytosolic side of the inner membrane and not with the periplasmic I layer of the core channel (B). It is worth noting that the dimensions of the hexameric TrwK structure shown here match perfectly with the base of the cryo-EM structure of the T4SS core complex (42).

FIGURE 8.

Model of interaction between the T4SS core complex and TrwK. The structure of the T4SS core complex obtained by cryo-EM (42) was retrieved from the EM Data Bank (emd_5031.map) and filtered to 20 Å. The hexameric structure of TrwK was fitted to the core complex in two possible locations: attached to the cytoplasmic side of the inner membrane region (A) or embedded in the I layer of the core complex (B), as described in Ref. 21. The model in A is more compatible with the presence of VirB3 subunit bound to the N terminus of VirB4.

Despite numerous genetic and biochemical studies, the biological function of VirB4 proteins is not fully understood. VirB4 proteins have been shown to play an important role in pilus biogenesis (11), but they have also been proposed to participate directly in the secretion of virulent factors (10, 12). Moreover, recent reports have shown that VirB4 proteins may interact directly with DNA (8, 23). Here, we conducted DNA shift assays to compare the abilities of TrwB and TrwK to bind DNA in vitro. We found that TrwK is able to bind DNA, albeit with much lower affinity than TrwB. Interestingly, we found that TrwK preferably binds G4-quadruplex structures, as has been observed for TrwB (16).

The structural homology of TrwK with TrwB led us to speculate about the possibility that these proteins could interact with each other to form heterocomplexes. In fact, it has already been shown that PrgJ, the VirB4 homologue in E. faecalis, is able not only to bind DNA but also to interact with PcfC, the coupling protein in the E. faecalis pCF10 plasmid (23). This result led the authors to propose a model in which the coupling protein would bind to the relaxome through contacts with the relaxase and the auxiliary protein (TrwC and TrwA in the R388 system, respectively), and then it would interact with the VirB4 homologue, which, in turn, would catalyze substrate transfer to the membrane translocase. Reinforcing this idea, we found that TrwB ATPase activity is inhibited by the presence of TrwK, an indication that there is an interaction between the two proteins. In the conjugative “shoot and pump” model (17), the relaxase is first transported covalently bound to the 5′ end of the DNA. If VirB4 proteins are involved in this protein substrate transport, TrwB/VirD4 proteins would be required in the next step to pump the plasmidic DNA through the channel. Therefore, once the DNA is inside the channel, and because of the high affinity that TrwB shows for DNA in comparison to TrwK, the latter motor would be substituted by TrwB, and, therefore, it could be possible that the two proteins could form transient heterohexameric complexes during the conjugative process.

In summary, the three-dimensional reconstruction of TrwK together with the biochemical and phylogenetic analysis reported here open new avenues in the understanding of the function and evolution of VirB4 proteins. Whether the in vitro DNA binding abilities and structural homologies of VirB4 with DNA translocases are a reflection of an in vivo mechanism or whether they are just a reminiscence of a common evolutionary history is hard to tell. Further experiments are needed to clarify the in vivo function of VirB4 proteins and their role in the molecular mechanism of secretion by T4SS.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Arranz at the Centro Nacional de Biotecnología (Madrid, Spain) and Drs. M. Lafarga and F. Madrazo at the Instituto Fundación Marqués de Valdecilla (Santander, Spain) for helpful assistance with the electron microscopy.

This work was supported by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (MINECO, Spain) Grants BFU2011-22874 (to E. C. and I. A), BFU2011-29038 (to J. L. C.), BFU2010-15703 (to J. M. V.), BFU2008-00995/BMC, and FP72009-248919 from the European VII Framework Program (to F. C.). This work was also supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the MINECO (to A. P.).

The map reported in this paper has been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (accession no. EM-5505).

- T4SS

- type IV secretion system

- ssDNA

- single-stranded DNA

- CTD

- C-terminal domain

- NTD

- N-terminal domain

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- 3D

- three-dimensional.

REFERENCES

- 1. Christie P. J., Atmakuri K., Krishnamoorthy V., Jakubowski S., Cascales E. (2005) Biogenesis, architecture, and function of bacterial type IV secretion systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59, 451–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Waters V. L. (1999) Conjugative transfer in the dissemination of β-lactam and aminoglycoside resistance. Front Biosci. 4, D433–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Christie P. J. (2004) Type IV secretion. The Agrobacterium VirB/D4 and related conjugation systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694, 219–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tato I., Zunzunegui S., de la Cruz F., Cabezon E. (2005) TrwB, the coupling protein involved in DNA transport during bacterial conjugation, is a DNA-dependent ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 8156–8161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rivas S., Bolland S., Cabezón E., Goñi F. M., de la Cruz F. (1997) TrwD, a protein encoded by the IncW plasmid R388, displays an ATP hydrolase activity essential for bacterial conjugation. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 25583–25590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ripoll-Rozada J., Peña A., Rivas S., Moro F., de la Cruz F., Cabezón E., Arechaga I. (2012) Regulation of the type IV 17408–17414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arechaga I., Peña A., Zunzunegui S., del Carmen Fernandez-Alonso M., Rivas G., de la Cruz F. (2008) ATPase activity and oligomeric state of TrwK, the VirB4 homologue of the plasmid R388 type IV secretion system. J. Bacteriol. 190, 5472–5479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Durand E., Oomen C., Waksman G. (2010) Biochemical dissection of the ATPase TraB, the VirB4 homologue of the E. coli pKM101 conjugation machinery. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2315–2323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fernández-López R., Garcillán-Barcia M. P., Revilla C., Lázaro M., Vielva L., de la Cruz F. (2006) Dynamics of the IncW genetic backbone imply general trends in conjugative plasmid evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30, 942–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berger B. R., Christie P. J. (1993) The Agrobacterium tumefaciens virB4 gene product is an essential virulence protein requiring an intact nucleoside triphosphate-binding domain. J. Bacteriol. 175, 1723–1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kerr J. E., Christie P. J. (2010) Evidence for VirB4-mediated dislocation of membrane-integrated VirB2 pilin during biogenesis of the Agrobacterium VirB/VirD4 type IV secretion system. J. Bacteriol. 192, 4923–4934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rabel C., Grahn A. M., Lurz R., Lanka E. (2003) The VirB4 family of proposed traffic nucleoside triphosphatases. Common motifs in plasmid RP4 TrbE are essential for conjugation and phage adsorption. J. Bacteriol. 185, 1045–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dang T. A., Christie P. J. (1997) The VirB4 ATPase of Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a cytoplasmic membrane protein exposed at the periplasmic surface. J. Bacteriol. 179, 453–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Middleton R., Sjölander K., Krishnamurthy N., Foley J., Zambryski P. (2005) Predicted hexameric structure of the Agrobacterium VirB4 C terminus suggests VirB4 acts as a docking site during type IV secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1685–1690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peña A., Ripoll-Rozada J., Zunzunegui S., Cabezón E., de la Cruz F., Arechaga I. (2011) Autoinhibitory regulation of TrwK, an essential VirB4 ATPase in type IV secretion systems. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 17376–17382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matilla I., Alfonso C., Rivas G., Bolt E. L., de la Cruz F., Cabezon E. (2010) The conjugative DNA translocase TrwB is a structure-specific DNA-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17537–17544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cabezon E., de la Cruz F. (2006) TrwB. An F(1)-ATPase-like molecular motor involved in DNA transport during bacterial conjugation. Res. Microbiol. 157, 299–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gomis-Rüth F. X., Moncalián G., Pérez-Luque R., González A., Cabezón E., de la Cruz F., Coll M. (2001) The bacterial conjugation protein TrwB resembles ring helicases and F1-ATPase. Nature 409, 637–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Iyer L. M., Makarova K. S., Koonin E. V., Aravind L. (2004) Comparative genomics of the FtsK-HerA superfamily of pumping ATPases. Implications for the origins of chromosome segregation, cell division and viral capsid packaging. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 5260–5279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cabezon E., Lanza V. F., Arechaga I. (2012) Membrane-associated nanomotors for macromolecular transport. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 23, 537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walldén K., Williams R., Yan J., Lian P. W., Wang L., Thalassinos K., Orlova E. V., Waksman G. (2012) Structure of the VirB4 ATPase, alone and bound to the core complex of a type IV secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 11348–11353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dang T. A., Zhou X. R., Graf B., Christie P. J. (1999) Dimerization of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB4 ATPase and the effect of ATP-binding cassette mutations on the assembly and function of the T-DNA transporter. Mol. Microbiol. 32, 1239–1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li F., Alvarez-Martinez C., Chen Y., Choi K. J., Yeo H. J., Christie P. J. (2012) Enterococcus faecalis PrgJ, a VirB4-like ATPase, mediates pCF10 conjugative transfer through substrate binding. J. Bacteriol. 194, 4041–4051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miroux B., Walker J. E. (1996) Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli. Mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J. Mol. Biol. 260, 289–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kreuzer K. N., Jongeneel C. V. (1983) Escherichia coli phage T4 topoisomerase. Methods Enzymol. 100, 144–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mindell J. A., Grigorieff N. (2003) Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 142, 334–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Scheres S. H., Nunez-Ramirez R., Sorzano C. O., Carazo J. M., Marabini R. (2008) Image processing for electron microscopy single-particle analysis using XMIPP. Nat. Protoc. 3, 977–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scheres S. H., Valle M., Nuñez R., Sorzano C. O., Marabini R., Herman G. T., Carazo J. M. (2005) Maximum-likelihood multi-reference refinement for electron microscopy images. J. Mol. Biol. 348, 139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pascual-Montano A., Donate L. E., Valle M., Bárcena M., Pascual-Marqui R. D., Carazo J. M. (2001) A novel neural network technique for analysis and classification of EM single-particle images. J. Struct. Biol. 133, 233–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Crowther R. A., Amos L. A. (1971) Harmonic analysis of electron microscope images with rotational symmetry. J. Mol. Biol. 60, 123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ludtke S. J., Baldwin P. R., Chiu W. (1999) EMAN. Semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J. Struct. Biol. 128, 82–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Massey T. H., Mercogliano C. P., Yates J., Sherratt D. J., Löwe J. (2006) Double-stranded DNA translocation. Structure and mechanism of hexameric FtsK. Mol. Cell 23, 457–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wriggers W., Milligan R. A., McCammon J. A. (1999) Situs: A package for docking crystal structures into low-resolution maps from electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 125, 185–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Notredame C., Higgins D. G., Heringa J. (2000) T-Coffee. A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 302, 205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Price M. N., Dehal P. S., Arkin A. P. (2009) FastTree. Computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 1641–1650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Han M. V., Zmasek C. M. (2009) phyloXML. XML for evolutionary biology and comparative genomics. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vogelmann J., Ammelburg M., Finger C., Guezguez J., Linke D., Flötenmeyer M., Stierhof Y. D., Wohlleben W., Muth G. (2011) Conjugal plasmid transfer in Streptomyces resembles bacterial chromosome segregation by FtsK/SpoIIIE. EMBO J. 30, 2246–2254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Williamson J. R. (1994) G-quartet structures in telomeric DNA. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 23, 703–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hishida T., Han Y. W., Fujimoto S., Iwasaki H., Shinagawa H. (2004) Direct evidence that a conserved arginine in RuvB AAA+ ATPase acts as an allosteric effector for the ATPase activity of the adjacent subunit in a hexamer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9573–9577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Batchelor R. A., Pearson B. M., Friis L. M., Guerry P., Wells J. M. (2004) Nucleotide sequences and comparison of two large conjugative plasmids from different Campylobacter species. Microbiology 150, 3507–3517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fronzes R., Schäfer E., Wang L., Saibil H. R., Orlova E. V., Waksman G. (2009) Structure of a type IV secretion system core complex. Science 323, 266–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]