Background: Interleukin-6 signaling requires assembly of a ternary IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 complex.

Results: Determination of the mIL-6 structure allowed detailed structural and sequence comparisons with hIL-6, predicting the primacy of sites in driving IL-6/IL-6Rα-gp130 interactions, which was confirmed by binding experiments.

Conclusion: Interactions between gp130 domain-1 and IL-6/IL-6Rα drive signaling complex assembly.

Significance: This suggests a pathway for evolution of signaling complex assembly and strategies for therapeutic targeting.

Keywords: Cytokine, NMR, Protein Complexes, Structural Biology, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Abstract

A number of secreted cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), are attractive targets for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. We have determined the solution structure of mouse IL-6 to assess the functional significance of apparent differences in the receptor interaction sites (IL-6Rα and gp130) suggested by the fairly low degree of sequence similarity with human IL-6. Structure-based sequence alignment of mouse IL-6 and human IL-6 revealed surprising differences in the conservation of the two distinct gp130 binding sites (IIa and IIIa), which suggests a primacy for site III-mediated interactions in driving initial assembly of the IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 ternary complex. This is further supported by a series of direct binding experiments, which clearly demonstrate a high affinity IL-6/IL-6Rα-gp130 interaction via site III but only weak binding via site II. Collectively, our findings suggest a pathway for the evolution of the hexameric, IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 signaling complex and strategies for therapeutic targeting. We propose that the signaling complex originally involved specific interactions between IL-6 and IL-6Rα (site I) and between the D1 domain of gp130 and IL-6/IL-6Rα (site III), with the later inclusion of interactions between the D2 and D3 domains of gp130 and IL-6/IL-6Rα (site II) through serendipity. It seems likely that IL-6 signaling benefited from the evolution of a multipurpose, nonspecific protein interaction surface on gp130, now known as the cytokine binding homology region (site II contact surface), which fortuitously contributes to stabilization of the IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 signaling complex.

Introduction

IL-6 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine, which plays key roles in both innate immunity and acquired immune responses. Impaired regulation of IL-6 production often contributes to the development of chronic inflammation. IL-6 stimulates antibody production by B cells and also the differentiation of Th17 lineage T cells, which are both crucial events in experimental models of autoimmune diseases. Predictably, overproduction of IL-6 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (for reviews, see Refs. 1–3).

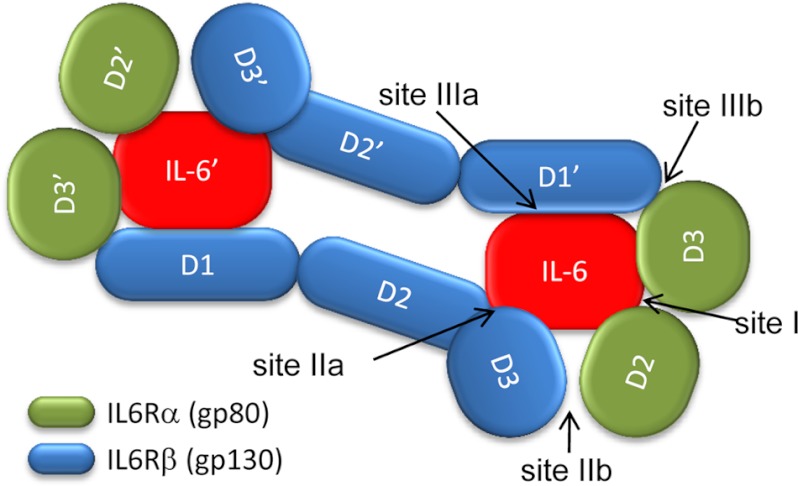

The IL-6 family of cytokines signal via the activation of JAK (Janus kinase) tyrosine kinases, leading to the activation of STAT (signal transducers and activators of transcription) transcription factors, which regulate a range of target genes (4). The initial event in IL-6 signaling involves the formation of a nonsignaling complex between IL-6 and its specific receptor (IL-6Rα),2 which leads to recruitment of gp130 to the complex through interactions with its extracellular domains and the formation of a hexameric signaling complex (5), as illustrated in Fig. 1. X-ray crystallographic and cryo-electron microscopy studies have revealed the molecular organization of this complex (6, 7), in which IL-6 interacts with both subunits of IL-6Rα (D2 and D3) via a conserved site (site I). Regions within both proteins of the IL-6/IL-6Rα complex are involved in binding to the cytokine binding homology region (CHR) of gp130 (fibronectin type III domains D2 and D3), with this composite interface defined as site II. Additional interactions are made via another shared site (site III) with a second molecule of gp130 through its immunoglobulin-like activation domain (D1). The three distinct interaction surfaces allow assembly of a stable, ternary signaling complex composed of two molecules of each component (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 signaling complex. The formation of a hexameric signaling complex is strongly supported by crystallographic data (6, 7) and includes two molecules of each component: IL-6 (red); IL-6Rα (green, D2 and D3 domains); and gp130 (blue, D1, D2 and D3 domains). Five distinct protein interaction sites are highlighted.

In this study, we report the solution structure of mouse IL-6, detailed analysis of the conservation of functional sites involved in signaling complex assembly, and a series of binding experiments designed to assess the relative importance of specific interaction sites in ternary complex formation. The structure obtained for mIL-6 confirmed its assignment as the ortholog of human IL-6 despite the low degree of sequence homology (40% identity), and structure-based sequence alignment allowed comparison of the IL-6Rα and gp130 interaction sites on human and mouse IL-6 (6, 8, 9). This revealed surprising differences in the conservation of the two distinct gp130 binding sites (site IIa and site IIIa, Fig. 1), which suggests a greater importance for site III interactions in mediating initial ternary complex assembly. This possibility was further investigated by a series of direct binding experiments, which strongly support the primacy of site III-mediated interactions in driving ternary complex formation. The work reported suggests a mechanism for the evolution of the hexameric signaling complex and highlights specific interaction sites for therapeutic targeting.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification

A mature form of mIL-6 (residues 27–211) with an additional five residues at the N terminus (Gly-Ala-Met-Gly-Ser) was produced using a pET-21-based Escherichia coli expression vector, which included an N-terminal His6 tag with a TEV protease cleavage site in the linker. Tuner (DE3) pLysS cells (Novagen) transformed with the mIL-6 expression vector were grown at 37 °C in medium containing 100 μg/ml carbenicillin to an A600 of ∼0.8 and then cooled to 25 °C, and mIL-6 expression was induced overnight by the addition of 10 μm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. Cells were harvested and lysed, and the His6-tagged mIL-6 was purified using a Ni-NTA column (Qiagen). The His tag was subsequently removed by incubation of the purified protein with TEV protease (TEV:mIL-6 1:15 w/w) at room temperature overnight followed by a second round of Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. Fractions containing mIL-6 were subsequently dialyzed into 20 mm sodium phosphate and 100 mm sodium chloride buffer at pH 6.4 and subjected to a final gel filtration purification step on a Superdex 75 16/60 column. The mature human IL-6 (hIL-6, residues 28–212) was prepared using an analogous pET-21-based E. coli expression vector (N-terminal His6 tag with a TEV protease cleavage site), with expression carried out in Origami B (DE3) cells induced by the addition of 100 μm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside and grown overnight at 17 °C. The soluble hIL-6 produced was harvested and purified essentially as described for mIL-6.

Uniformly 15N- and 15N/13C-labeled mIL-6 was produced from cells grown in minimal medium containing 1 g/liter 15N ammonium sulfate and, if appropriate, 2 g/liter d-[13C]glucose as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources. To improve the quality of the 13C/1H HSQC-NOESY spectra, 15N/13C-labeled samples of mIL-6 were prepared that contained nonlabeled aromatic residues (Phe, Tyr, Trp, and His), which was achieved by the addition of 50 mg/l of nonlabeled amino acids to the minimal medium.

The human IL-6Rα-IL-6 fusion protein was expressed with a cleavable N-terminal His6 tag in CHO cells and is similar to the hyper IL-6 fusion protein described previously (10). The soluble IL-6Rα-IL-6 was initially harvested from cell culture supernatants by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography followed by removal of the His6 tag by TEV protease treatment. The released His6 tag and any remaining His6-tagged fusion protein were removed by a second round of Ni-NTA affinity chromatography prior to a final gel filtration step on a Sephacryl S200 16/60 column, which yielded highly purified, monomeric IL-6Rα-IL-6. The series of C-terminal Fc fusion proteins containing selected extracellular regions of human gp130 (D1 and D2D3) or human IL-6Rα (D1D2D3) was also expressed in CHO cells and purified as described previously (11). This briefly involved isolation of the soluble gp130-Fc or IL-6Rα-Fc fusion proteins from culture supernatants by protein A affinity chromatography followed by gel filtration on a Sephacryl S200 16/60 column. The pure human oncostatin M and human gp130 extracellular region-Fc fusion protein (domains D1 to D6) were obtained from R&D Systems.

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR spectra were acquired from 0.35-ml samples of mIL-6 (250–430 μm) in a 20 mm sodium phosphate and 100 mm sodium chloride buffer at pH 6.4 (95% H2O, 5% D2O or 100% D2O). All NMR experiments were collected at 25 °C on either 600-MHz or 800-MHz Bruker spectrometers equipped with triple-resonance (15N/13C/1H) cryo-probes. A series of double- and triple-resonance spectra was recorded to determine essentially complete sequence-specific resonance assignments for mIL-6, as described previously (12–14). 1H-1H distance constraints required to calculate the structure of mIL-6 were derived from NOEs identified in NOESY, 15N/1H NOESY-HSQC, and 13C/1H HMQC-NOESY spectra, which were acquired with an NOE mixing time of 100 ms. Residues involved in stable backbone hydrogen bonds were identified by monitoring the rate of backbone amide exchange in two-dimensional 15N/1H HSQC spectra of mIL-6 dissolved in D2O.

Structural Calculations

The family of converged mIL-6 structures was calculated using CYANA 2.1 (15). Initially, the combined automated NOE assignment and structure determination (CANDID) protocol was used to automatically assign the NOE cross-peaks identified in two-dimensional NOESY and three-dimensional 15N- and 13C-edited NOESY spectra and to produce preliminary structures. Subsequently, several cycles of simulated annealing combined with redundant dihedral angle constraints (REDAC) were used to produce the final converged mIL-6 structures (16). Analysis of the family of converged structures obtained was carried out using the programs CYANA, MOLMOL, iCING, and PyMOL (15, 17–19).

Protein Sequence Alignments

The sequence alignments for human and mouse IL-6, IL-6Rα, and gp130 were generated using ClustalW (20). Structure-based sequence alignments of mIL-6 with both free and signaling complex-associated hIL-6 (IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130, Protein Data Bank (PDB) accession codes 1IL6 and 1P9M, respectively) were obtained by detailed comparisons of the structures in PyMOL and sequence analysis in JalView (21).

Surface Plasmon Resonance

All surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments were carried out on a Biacore 3000 system using a pH 7.4 running buffer containing 10 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.005% (v/v) P20. Proteins were attached to the surface of CM5 sensor chips (GE Healthcare) by the amine coupling method, as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, the carboxymethyl dextran surface was activated with a fresh mixture of 50 mm N-hydroxysuccinimide and 200 mm 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide for 5 min at a flow rate of 10 μl/min. The gp130-Fc and IL-6Rα-IL-6 fusion proteins were covalently coupled to chips at 7.5 and 2 μg/ml, respectively, in a 10 mm acetate, pH 5.0 buffer using a 5-min pulse at the same flow rate. Finally, the surface was deactivated with a 10-min pulse of 1 m ethanolamine HCl, pH 8.5. Reference flow cells were prepared for each type of chip produced by omitting the protein from the above procedure.

Binding of Native and Single-residue Variants of gp130-D1 to IL-6Rα-IL-6 Fusion

A series of purified native and variant gp130-D1-Fc fusion proteins (E23A, L24A, and L25A) was diluted in running buffer over the range 25–250 nm and pulsed over reference and IL-6Rα-IL-6 fusion flow cells for 4 min followed by a 5-min dissociation phase in running buffer. The chip surfaces were regenerated with a 40-s pulse of 2 m guanidine HCl at 30 μl/min. Sensorgrams were obtained as the response unit difference between the immobilized protein and reference cell.

Relative Binding of Functional Partners and Complexes to Extracellular Regions of gp130

Solutions of hIL-6, IL-6Rα-D1D2D3-Fc, oncostatin M, and an equimolar mixture of hIL-6 and IL-6Rα-D1D2D3-Fc were prepared in SPR running buffer at a concentration of 50 nm. The individual samples were each pulsed at 20 μl/min over immobilized gp130-D1-Fc, gp130-D2D3-Fc, or gp130-D1D2D3D4D5D6-Fc fusion proteins for 150 s, and a binding response report point was taken 10 s into the dissociation phase. The chip surfaces were regenerated with a 60-s pulse of 2.5 m guanidine HCl at 30 μl/min. The relative binding of functional partners and complexes to immobilized gp130-Fc fusion proteins was determined by normalizing the report point responses obtained by the molecular weight ratios for the appropriate binding partners to gp130-Fc constructs and by correcting for any differences in the efficiency of the coupling of gp130 proteins to sensor chips.

RESULTS

Solution Structure of mIL-6

Comprehensive sequence-specific backbone and side-chain resonance assignments were obtained for mIL-6 using a proven combination of triple-resonance experiments, as described previously (22). Backbone amide signals (15N and 1H) were assigned for all residues apart from Thr-27–Ser-28, Gln-94–Gly-116, and Lys-177–Thr-189, which were not detectable, probably due to line broadening arising from conformational exchange processes in the affected regions. Assignments obtained for nonexchangeable side-chain signals were over 84.5% complete (nearly 95% complete for regions of the protein with assigned backbone resonances).

The completeness of the 15N, 13C, and 1H resonance assignments obtained for mIL-6 allowed automated assignment of the NOEs identified in three-dimensional 15N/1H NOESY-HSQC and 13C/1H HMQC-NOESY and in the aromatic to aliphatic region of two-dimensional NOESY spectra using the combined automated NOE assignment and structure determination (CANDID) procedure implemented in CYANA (15). This approach proved very successful and yielded unique assignments for 94.2% (3863/4103) of the NOE peaks observed, which provided 2914 nonredundant 1H-1H distance constraints. In the final round of structural calculations, 52 satisfactorily converged mIL-6 structures were obtained from 100 random starting conformations using a total of 3418 NMR-derived structural constraints (an average of 18 constraints per residue). Table 1 contains a detailed summary of the constraints included in the calculations, together with the structural statistics for the family of structures obtained.

TABLE 1.

NMR constraints and structural statistics for mIL-6

| Number of constraints used in the final structural calculations | ||

| Intraresidue NOEs | 713 | |

| Sequential NOEs (i, i +1) | 725 | |

| Medium-range NOEs (i, i > 1 i ≤ 4) | 978 | |

| Long-range NOEs (i, i ≥ 5) | 498 | |

| Torsion angles | 204 (102 Φ and 102 Ψ) | |

| Backbone hydrogen bonds | 300 (75 hydrogen bonds) | |

| Maximum and total constraint violations in the 52 converged structures | ||

| Upper distance limits (Å) | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 4.0 ± 0.9 |

| van der Waals contacts (Å) | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 5.4 ± 0.9 |

| Torsion angle ranges (°) | 2.06 ± 0.45 | 14.3 ± 2.8 |

| Average CYANA target function (Å2) | 1.13 ± 0.27 | |

| Structural statistics for the family of 52 converged mIL-6 structures | ||

| Residues within allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot | 98.9% | |

| Backbone atom r.m.s.d. for structured regions (residues 24–68, 92–139, 165–187) | 0.64 ± 0.13 Å | |

| Heavy atom r.m.s.d. for structured regions (residues 24–68, 92–139, 165–187) | 1.26 ± 0.13 Å | |

| WHAT IF Z-scores (residues 1–72, 93–155, 165–190) | ||

| First generation packing quality | 1.19 ± 0.42 | |

| Second generation packing quality | 3.97 ± 0.87 | |

| χ1/χ2 rotamer normality | −6.96 ± 0.27 | |

| Backbone conformation | 0.84 ± 0.28 | |

The solution structure of mIL-6 has been determined to relatively high precision, which is clearly evident from the overlay of the protein backbone shown for the family of converged structures in Fig. 2A. This is also reflected in reasonably low root mean squared deviation (r.m.s.d.) values to the mean structure for both the backbone (0.64 ± 0.13 Å) and all heavy atoms (1.26 ± 0.13 Å, Table 1) of residues forming the well defined core of mIL-6 (Val-45–Lys-89, Ile-113–Leu-160, and Arg-186–Thr-208).

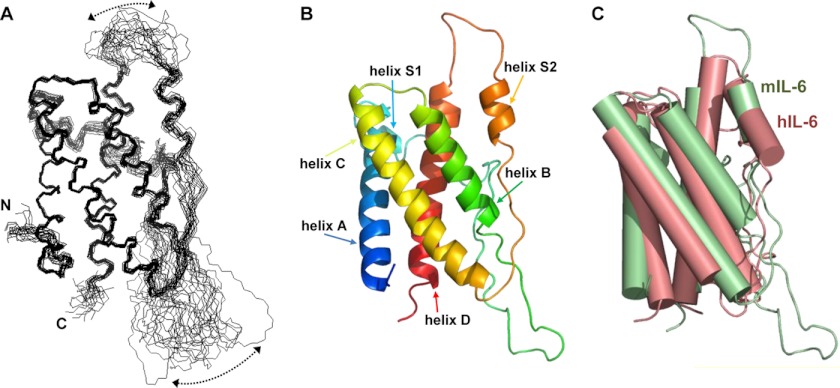

FIGURE 2.

Solution structure of mIL-6. A shows a best-fit superposition of the protein backbone (Val-45–Thr-208) for 20 out of 52 converged structures obtained for mIL-6, whereas B contains a ribbon representation of the backbone topology of the structure closest to the mean in the same orientation. The semi-flexible character of two loops is emphasized by arrows in A. C shows a comparison of the backbone topologies for mouse (green) and human (pink) IL-6.

mIL-6 contains four relatively long α-helices (helix A, Thr-48–Leu-69; helix B, Ser-114–Asn-129; helix C, Asn-134–Asp-159; and helix D, Arg-186–Thr-208), which form a four-helix bundle that is decorated by two shorter and less well defined α-helices (helix S1, Asp-75–Asn-86; and helix S2, Ile-169–Asp-176) and by several loops, as shown in Fig. 2B. The 25 N-terminal residues of the protein appear to be highly flexible and unstructured on the basis of the NMR data. The irregular loops connecting helical regions are a major feature of mIL-6, but differ widely in their length and properties. The short loop between helix A and helix S1 is fairly well defined, which probably reflects the presence of a disulfide bond between Cys-70 and Cys-76. This region is further stabilized by a network of favorable van der Waals contacts between helix S1 and helix D. The long loop between helix S1 and helix B is poorly defined by the NMR data and corresponds to a region in which many backbone amide signals are missing, which is consistent with the existence of multiple conformations in intermediate exchange on the NMR timescale. In contrast, the long loop between helices C and D, which includes the short S2 helix, is well defined apart from the region between helices S2 and D. These variable properties for the loop regions are reflected in the family of mIL-6 structures shown in Fig. 2A.

Comparison of the Structures of Mouse and Human IL-6

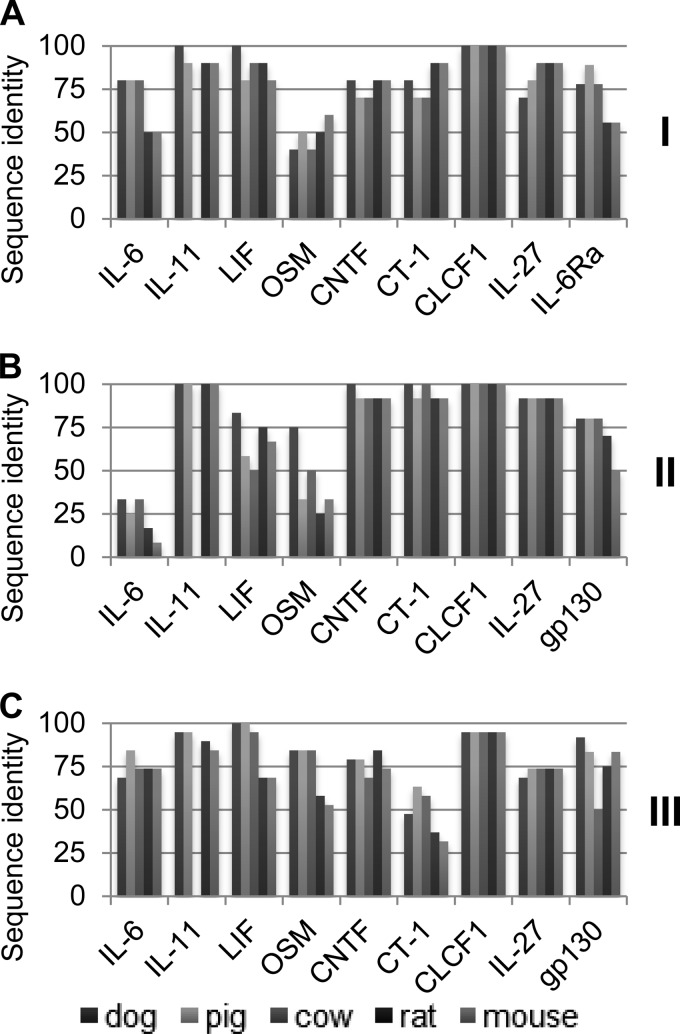

The predicted mouse ortholog of human IL-6 shares only 40% amino acid sequence identity and about 52% overall sequence homology (23, 24), which is surprisingly low when compared with all the other cytokines that signal through the gp130 receptor (interleukin-11 (88/92%), leukemia inhibitory factor (78/87%), ciliary neurotrophic factor (82/86%), cardiotrophin-1 (80/86%), cardiotrophin-like cytokine (97/99%), and interleukin-27 (69/73%)), apart from oncostatin M (42/50%). The remaining class I helical cytokines (25), which signal through a gp130-independent mechanism, also show a much higher degree of sequence homology (supplemental Fig. 1).

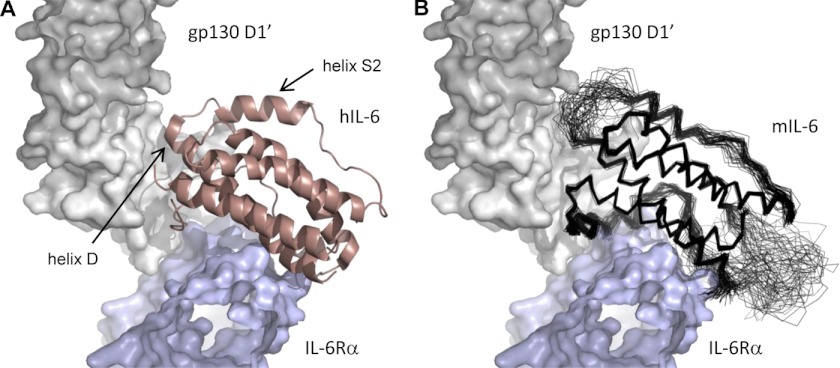

Determination of the solution structure of mIL-6 has allowed detailed comparisons with the previously reported structures for free and ternary signaling complex-bound hIL-6 (6, 8, 9). The human and mouse proteins are both characterized by a four-helix bundle at the heart of the structure, and despite the relatively low sequence homology, the positions and orientations of the four long α-helices in mIL-6 and hIL-6 are fairly well conserved, which is reflected in an r.m.s.d. of 1.8 Å for equivalent backbone atoms superimposed (Fig. 2C). The angles between pairs of helices differ by ∼16° for helix A when compared with helices B and C. In addition, helices A and C are somewhat longer in mIL-6 (3 and 7 residues, respectively), whereas helices B and D are significantly shorter (7 and 5 residues, respectively). Helix S1 is formed by 13 residues in mIL-6, and in contrast to either solution or crystal structures of hIL-6, it is well defined (8, 9), which implies that this region is more stable in mIL-6, perhaps reflecting a more extensive contact interface with the helical bundle. In the human hexameric signaling complex (Fig. 1), helix S1 is shared between sites I (IL-6/IL-6Rα) and IIIa (IL-6/gp130-D1) (6). The greater stability of this helix in mIL-6 may lead to higher affinity binding at these sites due to a lower entropic penalty. Interestingly, additional mobility seen in the hIL-6 S1 helix (8, 9) is maintained in the hexameric signaling complex (6). The loop between helices S2 and D is surprisingly similar in mIL-6 and hIL-6 (8, 9), which may reflect its conserved functional significance as part of the site III binding interface (Fig. 3). It is likely that this loop undergoes a conformational change on binding to the D1 domain of gp130 similar to that seen for hIL-6. Notable differences between mIL-6 and hIL-6 occur in the loop connecting helix S1 to helix B, which is significantly shorter in the human protein and results in reduced mobility in hIL-6 (8, 9). However, this region is not directly involved in signaling complex formation (6).

FIGURE 3.

Structural organization of site III in the IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 complex. A shows the features seen in the crystal structure determined for the hexameric IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 signaling complex (1P9M (6)). In B, the family of solution structures obtained for mIL-6 has been superimposed on hIL-6 to illustrate the similarity in the loop region connecting helices S2 and D, which makes key interactions between IL-6 and domain D1 of gp130 (site IIIa).

Conservation of Functional Sites on IL-6 and Cell Surface Receptors

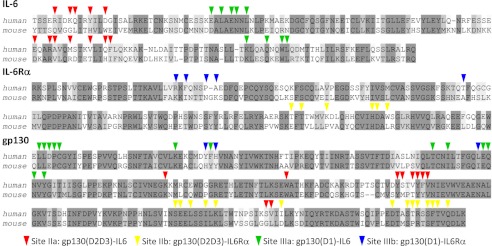

A structure-based sequence alignment of mouse and human IL-6, together with optimal sequence alignments for the interacting regions of the corresponding IL-6 receptors (IL-6Rα) and co-receptors (gp130), is shown in Fig. 4, which reveals significant variations in the conservation of regions involved in key interactions required to form the hexameric IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 signaling complex (6). The first stage of signaling complex formation involves the interaction of IL-6 with its dedicated receptor (IL-6Rα) through surface regions on both proteins defined as site I (6). The conservation of residues involved in this interaction is relatively high (50–80% identity) across a representative set of mammalian species, as shown in Figs. 4 and 5. The next stage in signaling complex assembly is proposed to be the interaction of the IL-6/IL-6Rα complex with the D2 and D3 domains of gp130 (IL-6Rβ) (6), which involves a cluster of 12 residues localized on helices A and C of IL-6 (site IIa). The region of IL-6 involved in this interaction is very poorly conserved across mammalian species (8–33% identity, Fig. 5B), with only a single residue unchanged between mouse and human (Fig. 4). In contrast, the complementary site IIa on gp130 is well conserved (50–80%, Figs. 4 and 5), with no evidence of changes introduced to compensate for residue changes in IL-6. This strongly suggests that contacts at site IIa stabilize rather than drive tertiary IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 complex formation. The lack of conservation of site IIa interactions contrasts markedly with the other interface involved in binding of IL-6 to gp130 (site IIIa), which is the most conserved on the protein (68–74%), as illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5C. This interface is mediated by the immunoglobulin-like D1 domain of gp130 and residues on IL-6 present in the flexible loop between helix S2 and helix D and also in helix S1 (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 4.

Conservation of functional sites between mouse and human orthologs of the IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 signaling complex. The figure shows a structure-based sequence alignment (top) encompassing the well defined regions of human (residues 48–211) and mouse IL-6 (residues 46–210), together with optimized sequence alignments for the interacting regions of human and mouse IL-Rα (residues 123–303 and 119–300, respectively, middle) and gp130 (residues 23–290 and 23–288, respectively, bottom). Identical residues are shaded in dark gray, and conserved residues are shaded in light gray. Arrows indicate the residues involved in specific protein interaction sites. The alignments were prepared with JalView (21).

FIGURE 5.

Conservation of interaction sites in class I helical cytokines that signal through gp130. The bar charts show the sequence identity of functional sites I (A), II (B), and III (C) for a representative selection of mammalian proteins when compared with the human sequences. For comparison, the conservation of the complementary sites on gp130 and IL-6Rα are also shown. LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; OSM, oncostatin-M; CNTF, ciliary neurotrophic factor; CT-1, cardiotrophin-1; CLCF1, cardiotrophin-like cytokine factor 1.

Roles of Specific Functional Sites in Mediating Binding of gp130 to IL-6/IL-6Rα Complex

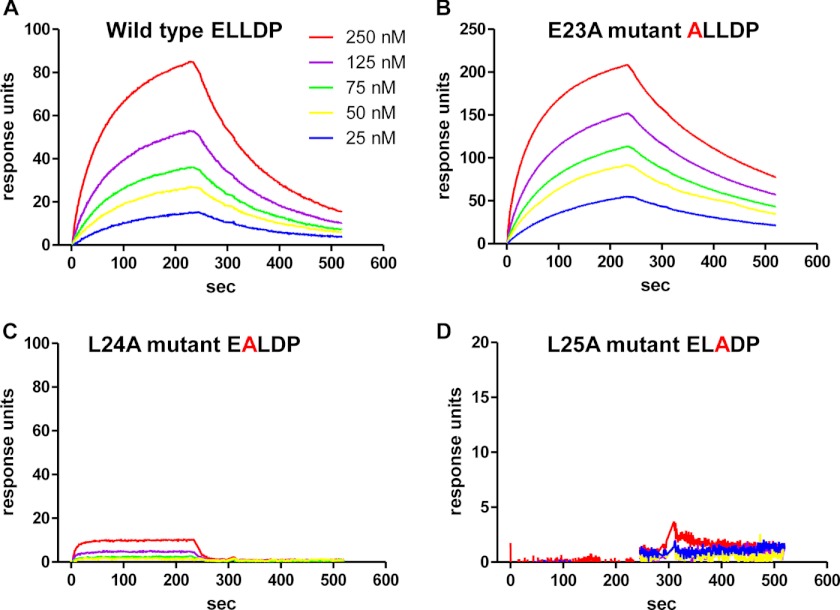

To directly assess the role of site IIIa in driving signaling complex formation, a series of SPR experiments was carried out to determine the affinity of the interaction between immobilized IL-6Rα-IL-6 fusion and native as well as variant gp130-D1-Fc fusion proteins (E23A, L24A, and L25A). The typical sensorgrams shown in Fig. 6 clearly demonstrate a high affinity interaction (Kd ∼25–75 nm) mediated by the D1 domain of gp130, which is dramatically reduced or abolished by just single-residue substitutions of conserved leucine residues (L24A and L25A) within the site IIIa region of gp130 (Fig. 4). Although highly conserved, these N-terminal residues play no role in stabilizing the structure of gp130-D1 (6), so the dramatic effects on binding resulting from the L24A and L25A substitutions almost certainly reflect the loss of key interactions with IL-6Rα-IL-6 rather than disruption of the structure of gp130-D1. The specificity of this interaction is further confirmed by the lack of any significant effect on binding of substitution of the preceding residue (E23A), which lies outside of the site IIIa interface.

FIGURE 6.

Binding of gp130 domain 1 (D1) to immobilized IL-6Rα-IL-6 fusion protein. Typical SPR sensorgrams are shown for native and single-residue variants of gp130-D1 binding to immobilized IL-6Rα-IL-6, with the responses obtained for the native (A) and E23A (B) proteins consistent with a relatively tight interaction (Kd ∼25–75 nm). The two site IIIa variants of gp130-D1 (C and D) show evidence of very little if any interaction with IL-6Rα-IL-6.

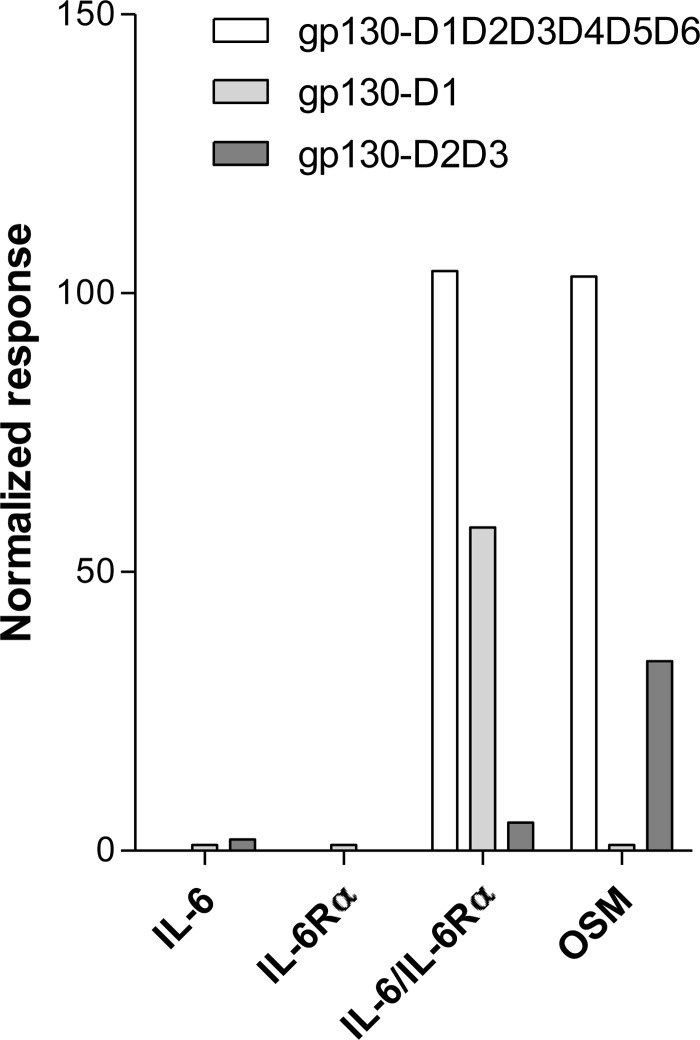

SPR measurements were also used to determine the relative affinities for binding of functional partners and complexes to selected extracellular regions of immobilized gp130 (D1, D2D3, and D1D2D3D4D5D6), and normalized dissociation phase report point responses from a typical series of experiments are shown in Fig. 7. The results clearly indicate that neither IL-6 nor IL-6Rα alone shows any stable interaction with the extracellular region of gp130, as expected from previously reported studies (6). In contrast, oncostatin M clearly forms a stable interaction with both the D1D2D3D4D5D6 and the D2D3 regions of gp130, which is consistent with previous work (6) and confirms the functional integrity of the gp130-Fc constructs. As expected, the IL-6/IL-6Rα complex shows a strong interaction with the complete extracellular region of gp130; however, only a fairly weak interaction is seen with the D2D3 region of gp130 in which the binding interface is restricted to site II. This relatively weak binding between IL-6/IL-6Rα and gp130-D2D3 contrasts markedly with the strong binding observed between the complex and gp130-D1 (Fig. 7), which clearly points to interactions mediated via site III as the principal drivers of ternary IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 complex formation. Collectively, the SPR results reported here, together with consideration of the sequence conservation of the distinct interaction sites (discussed above), strongly support the primacy of site III-mediated binding in driving ternary complex formation, with site II-mediated interactions facilitating the subsequent formation of the hexameric signaling complex. Previous work has also implied a critical role for gp130-D1 in ternary IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 complex formation, with the introduction of an N-terminal FLAG tag preceding Pro-27 of gp130 shown to severely impair the ability of the protein to interact with IL-6/IL-6Rα complex (26), which presumably reflects the loss of several conserved site IIIa residues (Leu-24, Leu-25, and Asp-26, Fig. 4).

FIGURE 7.

Relative binding of functional partners and complexes to gp130 extracellular regions. The histogram shown summarizes typical normalized report point responses obtained from the dissociation phases of SPR sensorgrams with immobilized gp130 extracellular regions (D1, D2D3, and D1D2D3D4D5D6) and IL-6, IL-6Rα, oncostatin M (OSM), or IL-6/IL-6Rα complex in solution. The responses seen highlight very rapid dissociation of both IL-6 and IL-6Rα from all regions of gp130, whereas gp130 constructs containing domain 1 show slow dissociation of the IL-6/IL-6Rα complex consistent with a tight interaction via site III.

DISCUSSION

The region of gp130 involved in site IIa interactions is known as the cytokine homology region and forms the binding site for a diverse range of cytokines utilizing gp130 as their co-receptor including IL-6, IL-11, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), and ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) (Fig. 5) (25, 27, 28). The features of this interaction site on gp130 reflect its broad specificity, with a fairly small (600 Å2) and shallow contact surface. In contrast, there is an extensive contact surface between gp130 and IL-6Rα at site IIb (1100 Å2), which appears to contribute the majority of the specificity and affinity of interactions at site II (6). The second interface involved in binding of IL-6 to gp130 (site IIIa) is similarly rich in surface features and specific interactions between the proteins, as illustrated in Fig. 3, with contacts mediated by residues within domain 1 of gp130 and present in the flexible loop between helices S2 and D of IL-6 and in helix S1 (6). Interestingly, the surface of gp130 domain D1 involved in binding to IL-6/IL-6Rα is shared by IL-11, which appears to form a similar hexameric signaling complex (29, 30). This site is also used by a functional homolog of hIL-6 from Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (viral IL-6), which in contrast to IL-6 has no requirement to interact with IL-6Rα and signals via formation of a tetrameric viral IL-6/gp130 complex (31, 32). It has been proposed previously that interactions between IL-6/IL-6Rα and gp130 at site II (Fig. 1) facilitate the initial formation of the ternary IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 complex (6). However, the contrasting conservation and features of sites II and III, together with directly comparative binding data indicating a significantly higher affinity interaction via site III, strongly suggest that binding via site III is likely to drive initial formation of the ternary complex, whereas site II-mediated interactions are likely to facilitate subsequent formation of the hexameric signaling complex.

At first glance, the sequence divergence in the site IIa interaction site of IL-6 across mammalian species (Fig. 5B) is somewhat surprising. However, it is likely that IL-6 sequences have been able to diverge here because of the essentially nonspecific nature of the site IIa interaction surface on gp130, which is a shared binding site for at least eight distinct cytokines signaling through gp130 (25). Our structural comparisons of the mouse and human IL-6 proteins, together with analysis of sequence conservation across mammalian species and binding experiments assessing the affinities of site II- and site III-mediated interactions, have clear implications in terms of evolution of the IL-6 signaling complex and strongly suggest that the system developed through specific interactions at sites I and III followed by later utilization of site II. It seems very probable that IL-6 signaling is simply taking advantage of the fact that site IIa of gp130 evolved into a multipurpose, fairly nonspecific protein interaction surface, which has fortuitously been enrolled in stabilization of a super-signaling IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130 complex.

The known biological roles of IL-6 make it an attractive target for therapeutic intervention in a number of major inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, and its extracellular location points to therapeutic antibodies as a viable approach. Clearly, consideration of the relative importance of specific protein interaction sites in signaling complex assembly and stabilization is an important factor in selecting antibodies as therapeutic candidates and highlights the value of detailed characterization of the properties and features of functional sites on target therapeutic proteins and complexes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Laura Griffin and Shirley Peters for help with some molecular biology aspects of the reported work and also Hanna Hailu, Robert Griffin, and Mandy Oxbrow for supporting the expression and purification of proteins required for the SPR experiments.

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2L3Y) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- IL-6Rα

- IL-6 receptor

- mIL-6

- mouse IL-6

- hIL-6

- human IL-6

- TEV

- tobacco etch virus

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean squared deviation

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum correlation

- HMQC

- heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jones S. A. (2005) Directing transition from innate to acquired immunity: defining a role for IL-6. J. Immunol. 175, 3463–3468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McInnes I. B., Schett G. (2007) Cytokines in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 429–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Finckh A., Gabay C. (2008) At the horizon of innovative therapy in rheumatology: new biologic agents. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 20, 269–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heinrich P. C., Behrmann I., Haan S., Hermanns H. M., Müller-Newen G., Schaper F. (2003) Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochem. J. 374, 1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Taga T., Kishimoto T. (1997) Gp130 and the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15, 797–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boulanger M. J., Chow D. C., Brevnova E. E., Garcia K. C. (2003) Hexameric structure and assembly of the interleukin-6/IL-6 α-receptor/gp130 complex. Science 300, 2101–2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Skiniotis G., Boulanger M. J., Garcia K. C., Walz T. (2005) Signaling conformations of the tall cytokine receptor gp130 when in complex with IL-6 and IL-6 receptor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 545–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu G. Y., Yu H. A., Hong J., Stahl M., McDonagh T., Kay L. E., Cumming D. A. (1997) Solution structure of recombinant human interleukin-6. J. Mol. Biol. 268, 468–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Somers W., Stahl M., Seehra J. S. (1997) 1.9 Ä crystal structure of interleukin 6: implications for a novel mode of receptor dimerization and signaling. EMBO J. 16, 989–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fischer M., Goldschmitt J., Peschel C., Brakenhoff J. P., Kallen K. J., Wollmer A., Grötzinger J., Rose-John S. (1997) I. A bioactive designer cytokine for human hematopoietic progenitor cell expansion. Nat. Biotechnol. 15, 142–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schroers A., Hecht O., Kallen K. J., Pachta M., Rose-John S., Grötzinger J. (2005) Dynamics of the gp130 cytokine complex: a model for assembly on the cellular membrane. Protein Sci. 14, 783–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Veverka V., Lennie G., Crabbe T., Bird I., Taylor R. J., Carr M. D. (2006) NMR assignment of the mTOR domain responsible for rapamycin binding. J. Biomol. NMR 36, 3–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Waters L. C., Böhm M., Veverka V., Muskett F. W., Frenkiel T. A., Kelly G. P., Prescott A., Dosanjh N. S., Klempnauer K. H., Carr M. D. (2006) NMR assignment and secondary structure determination of the C-terminal MA-3 domain of the tumour suppressor protein Pdcd4. J. Biomol. NMR 36, Suppl. 1, 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Renshaw P. S., Veverka V., Kelly G., Frenkiel T. A., Williamson R. A., Gordon S. V., Hewinson R. G., Carr M. D. (2004) Sequence-specific assignment and secondary structure determination of the 195-residue complex formed by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins CFP-10 and ESAT-6. J. Biomol. NMR 30, 225–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herrmann T., Güntert P., Wüthrich K. (2002) Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE assignment using the new software CANDID and the torsion angle dynamics algorithm DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 319, 209–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Güntert P., Wüthrich K. (1991) Improved efficiency of protein structure calculations from NMR data using the program DIANA with redundant dihedral angle constraints. J. Biomol. NMR 1, 447–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koradi R., Billeter M., Wüthrich K. (1996) MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DeLano W. L. (2010) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.3r1, Schrödinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 19. Doreleijers J. F., Sousa da Silva A. W., Krieger E., Nabuurs S. B., Spronk C. A., Stevens T. J., Vranken W. F., Vriend G., Vuister G. W. (2012) CING: an integrated residue-based structure validation program suite. J. Biomol. NMR, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I. M., Wilm A., Lopez R., Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G. (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clamp M., Cuff J., Searle S. M., Barton G. J. (2004) The Jalview Java alignment editor. Bioinformatics 20, 426–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Veverka V., Crabbe T., Bird I., Lennie G., Muskett F. W., Taylor R. J., Carr M. D. (2008) Structural characterization of the interaction of mTOR with phosphatidic acid and a novel class of inhibitor: compelling evidence for a central role of the FRB domain in small molecule-mediated regulation of mTOR. Oncogene 27, 585–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Simpson R. J., Moritz R. L., Rubira M. R., Van Snick J. (1988) Murine hybridoma/plasmacytoma growth factor. Complete amino-acid sequence and relation to human interleukin-6. Eur. J. Biochem. 176, 187–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tanabe O., Akira S., Kamiya T., Wong G. G., Hirano T., Kishimoto T. (1988) Genomic structure of the murine IL-6 gene. High degree conservation of potential regulatory sequences between mouse and human. J. Immunol. 141, 3875–3881 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang X., Lupardus P., Laporte S. L., Garcia K. C. (2009) Structural biology of shared cytokine receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 29–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moritz R. L., Ward L. D., Tu G. F., Fabri L. J., Ji H., Yasukawa K., Simpson R. J. (1999) The N-terminus of gp130 is critical for the formation of the high-affinity interleukin-6 receptor complex. Growth Factors 16, 265–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boulanger M. J., Garcia K. C. (2004) in Cell Surface Receptors Vol. 68 (Garcia K. C., ed), pp. 107–146, Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 28. Skiniotis G., Lupardus P. J., Martick M., Walz T., Garcia K. C. (2008) Structural organization of a full-length gp130/LIF-R cytokine receptor transmembrane complex. Mol. Cell 31, 737–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barton V. A., Hall M. A., Hudson K. R., Heath J. K. (2000) Interleukin-11 signals through the formation of a hexameric receptor complex. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 36197–36203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matadeen R., Hon W. C., Heath J. K., Jones E. Y., Fuller S. (2007) The dynamics of signal triggering in a gp130-receptor complex. Structure 15, 441–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoischen S. H., Vollmer P., März P., Ozbek S., Götze K. S., Peschel C., Jostock T., Geib T., Müllberg J., Mechtersheimer S., Fischer M., Grötzinger J., Galle P. R., Rose-John S. (2000) Human herpes virus 8 interleukin-6 homologue triggers gp130 on neuronal and hematopoietic cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 3604–3612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chow D., He X., Snow A. L., Rose-John S., Garcia K. C. (2001) Structure of an extracellular gp130 cytokine receptor signaling complex. Science 291, 2150–2155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.