Background: Histone deacetylases (HDACs) mediate cardiac development and diseases.

Results: HDAC inhibition promoted cardiac repairs and neovascularization, which were absent in KitW/KitW-v mice. Preconditioning of c-kit+ cardiac stem cells via HDAC inhibition increased myocardial regeneration.

Conclusion: HDAC inhibition promotes myocardial repair through c-kit signaling.

Significance: The study advances our knowledge of myocardial repair and development of a novel therapeutic strategy for heart diseases.

Keywords: Cell Therapy, Histone Deacetylase, Myocardial Infarction, Regeneration, Signal Transduction

Abstract

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) play a critical role in the regulation of gene transcription, cardiac development, and diseases. The aim of this study was to test whether inhibition of HDACs induces myocardial repair and cardiac function restoration through c-kit signaling in mouse myocardial infarction models. Myocardial infarction in wild type Kit+/+ and KitW/KitW-v mice was created following thoracotomy by applying permanent ligation to the left anterior descending artery. The HDAC inhibitor, trichostatin A (TSA, 0.1 mg/kg), was intraperitoneally injected daily for a consecutive 8 weeks after myocardial infarction. 5-Bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU, 50 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally delivered every other day to pulse-chase label in vivo endogenous cardiac replication. Eight weeks later, inhibition of HDACs in vivo resulted in an improvement in ventricular functional recovery and the prevention of myocardial remodeling in Kit+/+mice, which was eliminated in KitW/KitW-v mice. HDAC inhibition promoted cardiac repairs and neovascularization in the infarcted myocardium, which were absent in KitW/KitW-v mice. Re-introduction of TSA-treated wild type c-kit+ CSCs into KitW/KitW-v myocardial infarction heart restored myocardial functional improvement and cardiac repair. To further validate that HDAC inhibition stimulates c-kit+ cardiac stem cells (CSCs) to facilitate myocardial repair, GFP+ c-kit+ CSCs were preconditioned with TSA (50 nmol/liter) for 24 h and re-introduced into infarcted hearts for 2 weeks. Preconditioning of c-kit+ CSCs via HDAC inhibition with trichostatin A significantly increased c-kit+ CSC-derived myocytes and microvessels and enhanced functional recovery in myocardial infarction hearts in vivo. Our results provide evidence that HDAC inhibition promotes myocardial repair and prevents cardiac remodeling, which is dependent upon c-kit signaling.

Introduction

The acetylation and deacetylation of histones play a significant role in the regulation of gene transcription in many cell types (1, 2). Histone acetylation is mediated by histone acetyltransferase. The resulting modification in the structure of chromatin leads to nucleosomal relaxation and altered transcriptional activation. The reverse reaction is mediated by histone deacetylase, which induces deacetylation, chromatin condensation, and transcriptional repression (3–7). Inhibition of HDACs2 silences fetal gene activation, renders myocytes insensitive to hypertrophic agonists, mitigates cardiac hypertrophy, and prevents cardiac remodeling (8–10). In addition, we and others demonstrated that inhibition of HDACs protects the heart against acute ischemic injury (11–15).

Earlier studies demonstrated that disruption of c-kit impaired myocardial repair in infarcted hearts (16, 17). We have demonstrated that peripheral infusion of c-kit+ stem cells into infarcted hearts increased neovascularization and cardiac functional recovery (13). Pharmacological treatment induced myocardial regeneration via enhanced cardiac c-kit+ cell proliferation and differentiation in the heart (18). Notably, we have recently found that HDAC inhibition preserves cardiac performance and mitigates myocardial remodeling through stimulating cardiac repair, which is related to the increase in c-kit+ cardiac stem cells in post-myocardial infarction (19). It is interesting to investigate whether HDAC inhibition-induced myocardial repair and functional improvements are mediated through the c-kit signaling pathway.

It has now been recognized that adult hearts harbor distinct populations of cardiac progenitors (20–23), which have the potential to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, endothelia, and vascular smooth muscle cells. Recent studies suggest that stimulation of endogenous cardiac regeneration to achieve de novo cardiac repair is a critical mechanism of cardiac cell therapy (24, 25). It is unknown whether preconditioning of c-kit+ CSCs via HDAC inhibition with TSA could enhance myocardial repair and improve functional recovery when transplanted into MI hearts. In this study, by utilizing c-kit-deficient KitW/KitW-v mice, we have demonstrated that HDAC inhibition induces myocardial repair, prevents cardiac remodeling, and improves myocardial functional recovery through c-kit signaling. Furthermore, we have shown that HDAC inhibition preconditions c-kit+ CSCs to facilitate cardiac repair and neovascularization when re-introduced into the infarcted myocardium. The results provide new evidence to develop novel clinical therapeutic approaches for myocardial infarction.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Adult 3-month-old male Kit+/+mice and KitW/KitW-v mice were supplied by The Jackson Laboratory (Wilmington, MA). All animal experiments were conducted under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute, which conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

In Vivo Myocardial Infarction

The mouse myocardial infarction model was created following thoracotomy by applying permanent ligation to the left anterior descending artery. Briefly, anesthesia was produced by an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital at a dose of 50 mg/kg. During the surgical procedure, the adequacy of anesthesia will be monitored with a toe pinch testing to check the animal's reaction. Mice received a subcutaneous injection of buprenorphine (0.03 mg/kg) 2 h before surgery and also every 12 h post-surgery for 3 days. Mice were placed in a supine position on the operating table. Ventilation was achieved by connecting the endotracheal tube with a rodent ventilator (Harvard, model 683). The chest was then opened with tenotomy scissors. A 7-0 nylon suture was passed with a tapered needle under the left anterior descending coronary artery. Coronary occlusion was induced by ligation with a nylon suture. Upon completion of ligation, the chest was closed by a 5-0 Tricon suture with one layer through the chest wall and muscle and a second layer through the skin and subcutaneous material. We subjected both Kit+/+ mice and the KitW/KitW-v mice to myocardial infarction and randomized them into receiving an intraperitoneal injection of vehicle or TSA (0.1 mg/kg intraperitoneal) on a daily basis for 8 weeks. Sham animals underwent placement of the suture without ligation. In addition, additional Kit+/+ and the KitW/KitW-v sham mice were exposed to TSA treatments to serve as sham + TSA controls. We extended our experiments to which KitW/KitW-v MI hearts were re-introduced 5 × 105 c-kit+ CSCs from Kit+/+ mice, and this allowed us to see whether functional c-kit+ CSCs were essential for myocardial repair and functional restoration. At the end of experiments, animals were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (120 mg/kg).

Measurement of Ventricular Function

We used Langendorff's perfused heart preparation, and measurement of left ventricular function was performed. All mice were anesthetized with a lethal intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (120 mg/kg). Hearts were rapidly excised and arrested in ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit buffer. They were then cannulated via the ascending aorta for retrograde perfusion by the Langendorff method using Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing (in mm) 110 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4·7H2O, 2.5 CaCl2·2H2O, 11 glucose, 1.2 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 0.5 EDTA. The buffer, aerated with 95% O2-5% CO2 to give a pH of 7.4 at 37 °C, was perfused at a constant pressure of 55 mm Hg. Left ventricular functional analysis was performed using computer software and a computer-based recording system (BIOPAC, Goleta, CA). Measured parameters include left ventricular systolic pressure, heart rate, and left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP), where LVDP is systolic pressure minus left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, and rate pressure product (RPP). RPP will be expressed as the product of LVDP and heart rate. Left ventricular dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin were obtained. The measurement of left ventricular function is described previously (26).

Histological Analysis

Sections (10 μm) were prepared from paraffin-embedded tissues, and sections from apex, mid-left ventricle (LV), and base were stained with Masson's trichrome according to the manufacturer's protocol (Sigma). Images of the three sections, from the base to the apex of the left ventricle, were taken using an Olympus BX51 microscope with Spot Advanced software. Infarct scar area and total area of LV were traced manually and measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Wall thickness of left ventricle, viable myocardium, and scar size were measured. To quantitate the degree of LV dilation, the LV expansion index was calculated using a modification of the method (27) as follows: expansion index = (LV cavity area/total area) × (noninfarcted region wall thickness/risk region wall thickness).

Tissue and Cellular Immunocytochemistries

Cardiac tissues and sections were prepared from the paraffin-embedded hearts as described above. Tissue sections were de-paraffinized for 30 min at 70 °C and subsequently immersed in xylene and ethanol at decreasing concentrations. Slides were then washed in distilled water. Myocytes were identified by α-sarcomeric actinin and smooth muscle cells by anti-α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) monoclonal antibody (Sigma). BrdU was used to detect the proliferative cells (Roche Applied Science); Ki67 was used to detect the cycling cells (Novocastra, UK). c-Kit+ cardiac stem cells were labeled with c-kit antibodies (Abcam, UK). GFP-labeled c-kit+ CSC-derived myocytes were detected with polyclonal GFP antibody (Invitrogen). The total number of vessels from each group was calculated and normalized to the tissue area. The stained numbers of each section were counted in ∼20 randomized fields of the tissue sections, which were taken in the middle plane of each heart and contained infarct and border regions.

Isolation and Culture of c-kit+ CSCs

Adult male ICR mouse cardiac tissues were minced into small pieces and subjected to enzymatic dissociation, and the remaining tissue fragments were cultured as explants in explant medium (Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mmol/liter l-glutamine, and 0.1 mmol/liter 2-mercaptoethanol) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After 2–3 weeks, small phase-bright cells migrating above the fibroblast layer were formed from adherent explants. To enrich the c-kit+ cardiac stem cells, we sorted CD117+ cells from collected cells by positive selection with anti-CD117 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) using a magnetic cell sorter device from Miltenyi Biotec. Newly isolated c-kit+ cardiac cells were seeded at multiwell plates precoated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences) in media designated for cell growth medium (DMEM/F-12, 10% FBS, 200 mmol/liter l-glutamine, 1% nonessential amino acids, 0.1 mmol/liter β-mercaptoethanol, 1000 units/ml leukemia inhibitory factor, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin). Likewise, c-kit+ CSCs from Kit+/+ mice were also isolated and cultured as described above and utilized to reintroduce into KitW/KitW-v MI hearts.

Western Blot Analysis

We prepared samples from c-kit+ CSCs and myocardium and performed immunoblotting analysis. Proteins (50 μg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in 1× Tris-buffered saline containing 0.5% Tween 20 for 1 h. The blots were incubated with their respective polyclonal antibody (1:1000) for 2 h, visualized by incubation with anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000) for 1 h, and developed with ECL chemiluminescence detection reagent (Amersham Biosciences).

HDAC Activity Assay in Myocardium

Measurement of HDAC activity in cardiac tissue was conducted using the colorimetric HDAC activity assay kit (BioVision Research, Mountain View, CA).

Establishment of Stable GFP+ c-kit+ CSCs

To track the fate of transplanted CSCs in the infarcted hearts, a stable c-kit+ CSC cell line expressing GFP was established. Isolated c-kit+ cardiac stem cells were transfected with pEGFP using LipofectamineTM 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The transfected GFP-CSCs were selected with the maintenance of G418 (500 μg/liter) for 2 weeks, and positive colonies were picked up under fluorescent microscopy. Following identification of stably transfected c-kit+ CSC cells, c-kit+ CSCs were maintained and used for future studies.

In Vivo c-kit+ CSC Transplantations in MI Hearts

In another set of experiments, we performed the cell transplantation procedure in MI hearts; 5 × 105 c-kit+ CSCs were suspended in 10 μl of PBS and injected into five sites into the border zones of the ischemic LV of ICR mice. The TSA-treated c-kit+ CSC group is the same as above except that c-kit+ CSCs were stimulated with 50 nmol/liter for 24 h before cell implantation, whereas vehicle (ethanol) was used to treat c-kit+ CSCs as control. Sham animals underwent placement of the suture without ligation. Furthermore, additional sham animals receiving c-kit+ CSCs treated with or without TSA were also included to exclude the effects of c-kit+ CSCs on sham animals. Ventricular function was assessed 2 weeks following MI. The detailed methodology of MI, ventricular functional estimation, and immunochemical staining analysis are described as above. The newly formed myocardium within the heart was identified by the detection of GFP-positive cells in hearts injected with c-kit+ CSCs. The detection of GFP signal was used to recognize myocytes with α-sarcomeric actinin and microvessels with α-SMA.

Data Analysis

All data are expressed as means ± S.E. Differences among the groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni correction. Student's unpaired t test was used for two groups. A probability of p < 0.05 was considered to be a significant difference.

RESULTS

HDAC Inhibition Improves the Restoration of Cardiac Function in MI Hearts, Which Diminishes in KitW/KitW-v Mice

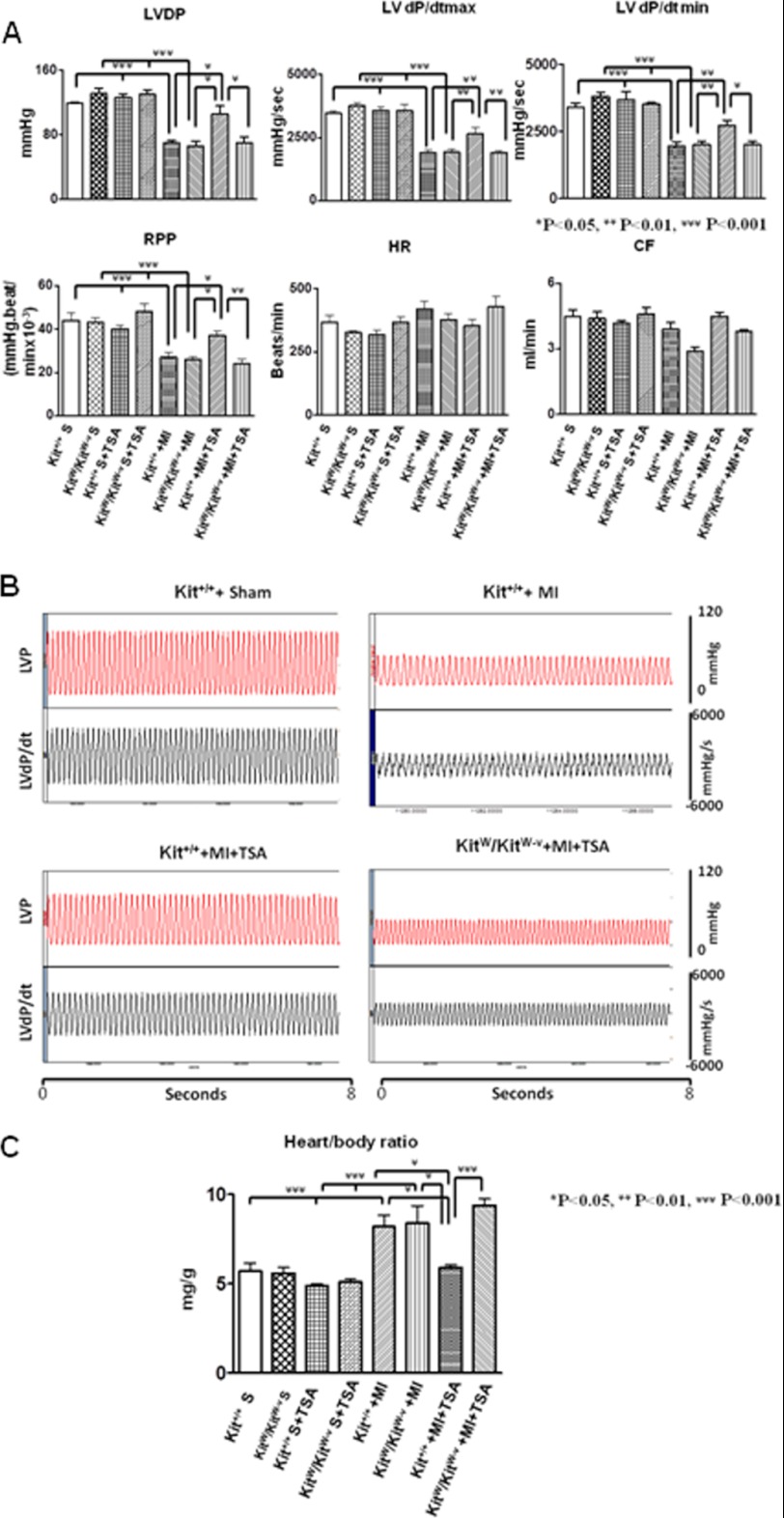

As shown in Fig. 1A, both base-line ventricular functions are indistinguishable in LV-dP/dtmax, LV-dP/dtmin, LV developed pressure, and rate pressure products between Kit+/+mice and KitW/KitW-v mice in the presence or absence of HDAC inhibition, suggesting that TSA treatments did not result in significant changes in cardiac functional parameters. In both Kit+/+ and KitW/KitW-v mice, myocardial infarction led to the depression of ventricular function (p < 0.05 versus sham groups). However, TSA treatment of infarcted Kit+/+mice significantly improved ventricular functional restoration in LV-dP/dtmax (2650 ± 233 mm Hg/s; 1890 ± 86 mm Hg/s, mean ± S.E. p < 0.01), and LV-dP/dtmin (2710 ± 216 mm Hg/s; 1997 ± 120 mm Hg/s, p < 0.05) showed a higher restoration than TSA-treated KitW/KitW-v MI animals. In the Kit+/+ MI animal, TSA treatment was also associated with an increase in left ventricular developed pressure (106 ± 10 mm Hg; 70 ± 8 mm Hg, p < 0.05) and rate pressure products (37.0 ± 2.0 × 103 mm Hg/min; 24.0 ± 2.2 × 103 mm Hg/min) as compared with TSA-treated KitW/KitW-v MI mice (Fig. 1, A and B). The recovery of LV-dP/dtmax and LV-dP/dtmin in TSA-treated KitW/KitW-v MI was not increased from control Kit+/+MI (1887 ± 109 mm Hg/s; 1943 ± 156 mm Hg/s) and control KitW/KitW-v MI hearts (1926 ± 156 mm Hg/s; 2006 ± 131 mm Hg/s), respectively. There was not a significant difference in heart rate among groups. Therefore, the favorable effects of HDAC inhibition on myocardial functional restoration completely deteriorated in the KitW/KitW-v MI mice. In addition, there was no significant differences in LV developed pressure and rate pressure products between control Kit+/+ MI and control KitW/KitW-v MI animals in the absence of TSA treatments, which was indistinguishable with TSA-treated KitW/KitW-v MI mice. In addition, TSA treatment slightly increased the coronary effluent in Kit+/+MI mice but abrogated the effluent in KitW/KitW-v MI mice, although there was no noticeable significant difference. As can been seen in Fig. 1C, the heart/body ratio, an index of hypertrophy, increased after myocardial infarction in both control Kit+/+MI and KitW/KitW-v MI mice as compared with sham controls. Hypertrophic response was reduced in the TSA-treated Kit+/+MI hearts (5.9 ± 0.2 mg/g), but the effect of TSA was diminished in KitW/KitW-v mice (9.4 ± 0.4 mg/g, p < 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

HDAC inhibition augments the restoration of ventricular function in Kit+/+mice but not in KitW/KitW-v mice. LV function was assessed in isovolumetric hearts after 8 weeks of MI. The measured parameters included LVDP, heart rate, and RPP, where LVDP is systolic pressure minus LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP). LV dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin were continuously recorded. Coronary effluent is in ml/min. A, left ventricular functions were determined from Kit+/+mice and KitW/KitW-v mice. B, representative left ventricular pressure record in sham (S), MI, Kit+/+ MI + TSA, and KitW/KitW-v + TSA MI hearts. C, measurements of heart/body ratio from sham, MI, Kit+/+, and KitW/KitW-v mouse infarcted hearts. HR, heart rate; CF, coronary effluents; LVP, left ventricular pressure. Values represent mean ± S.E., *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 (n = 5–9/group).

To further confirm the role of TSA-treated c-kit+ CSCs on myocardial functional improvement and anti-hypertrophic effects in post-MI heart, we re-introduced TSA-treated c-kit+ CSCs into KitW/KitW-v MI heart. As shown in supplemental Fig. S1, myocardial functional restoration and heart/body ratio after receiving TSA-treated c-kit+ CSCs in KitW/KitW-v MI could reach a level in Kit+/+ MI + TSA animals. These results suggest that HDAC inhibition improves ventricular functional restoration and the anti-hypertrophic effect, which require functional c-kit.

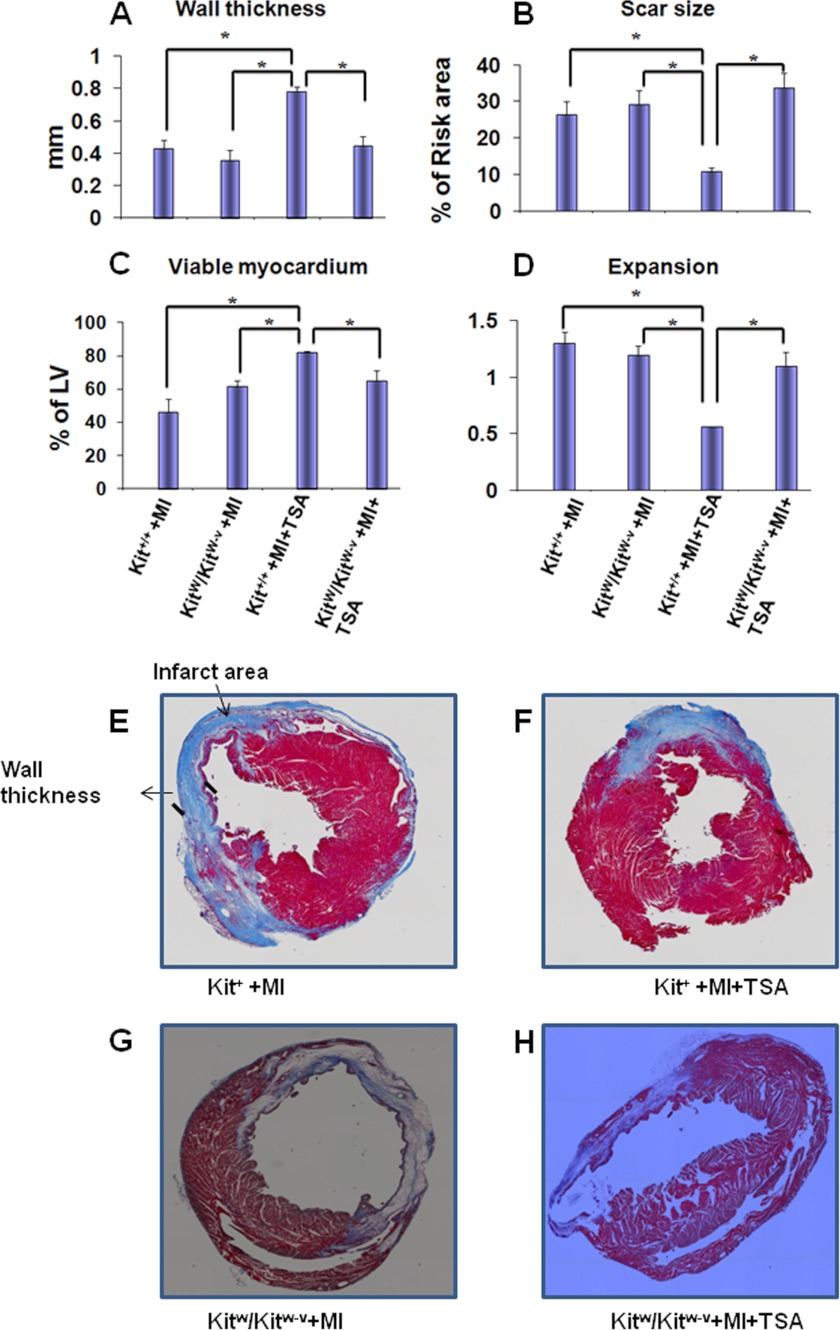

c-kit Dysfunction Diminishes Anti-cardiac Remodeling Effect of HDAC Inhibition in MI Hearts

Morphometric analysis of infarcted hearts shows severe LV chamber dilatation and infarcted wall thinning (Fig. 2, A–D and E–H). MI hearts that received HDAC inhibition illustrated attenuated LV remodeling, which demonstrated a more viable myocardium (82 ± 1%) and thicker infarcted ventricular wall in MI Kit+/+mice (0.78 ± 0.07 mm) than those of KitW/KitW-v MI mice (65 ± 6%; 0.45 ± 0.05 mm, p < 0.05), respectively. There was no difference between control Kit+/+ MI (0.43 ± 0.05 mm) and control KitW/KitW-v MI (0.38 ± 0.59 mm) mice in the absence of TSA treatments. HDAC inhibition reduced scar size in Kit+/+MI mice (11.0 ± 1.0%), in contrast to the results seen in KitW/KitW-v MI mice (33.7 ± 4.0%, p < 0.01). Scar size was comparable between control infarcted Kit+/+ and control KitW/KitW-v mice in the absence of TSA treatments (26.4 ± 3.5% and 29.3 ± 3.8%). HDAC inhibition resulted in less LV expansion in Kit+/+ mice as compared with KitW/KitW-v mice (0.56 ± 0.04; 1.1 ± 0.1, p < 0.05). However, without TSA treatments, there was no difference in LV expansion between control Kit+/+ MI and control KitW/KitW-v MI mice (1.3 ± 0.1; 1.2 ± 0.1). Therefore, the effects of HDAC inhibition on reducing cardiac remodeling were absent in KitW/KitW-v mice. The parameters aforementioned were indistinguishable between control Kit+/+MI mice and control KitW/KitW-v MI mice without HDAC inhibition. In addition, as shown in supplemental Fig. S2, re-introduction of TSA-treated c-kit+ CSCs into KitW/KitW-v MI heart reversed myocardial remodeling in control KitW/KitW-v MI heart. These observations indicate that HDAC inhibition prevents cardiac remodeling, which depends on c-kit.

FIGURE 2.

HDAC inhibition reduces myocardial remodeling. A–D, HDAC inhibition increased viable myocardium and wall thickness of infarcted myocardium but decreased scar sizes and the expansion index, which depends upon c-kit progenitors; E–H, representative Masson-trichrome stained myocardial sections from sham, MI, Kit+/+, and KitW/KitW-v mouse infarcted hearts. Values represent mean ± S.E., *, p < 0.05 (n = 3–5/group).

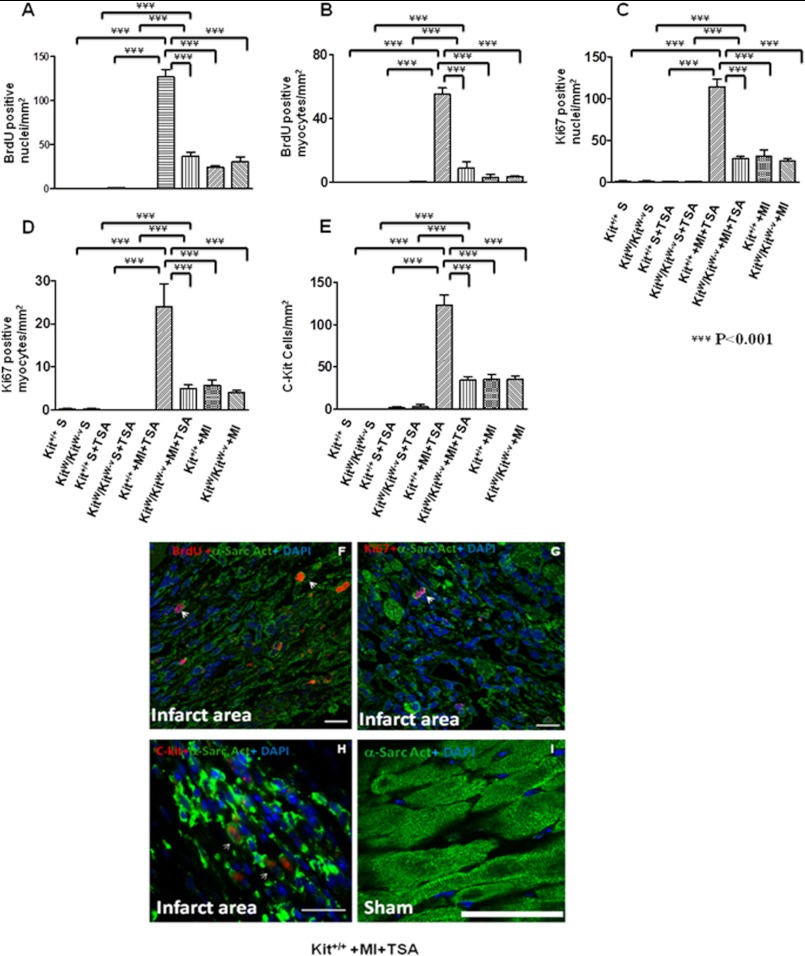

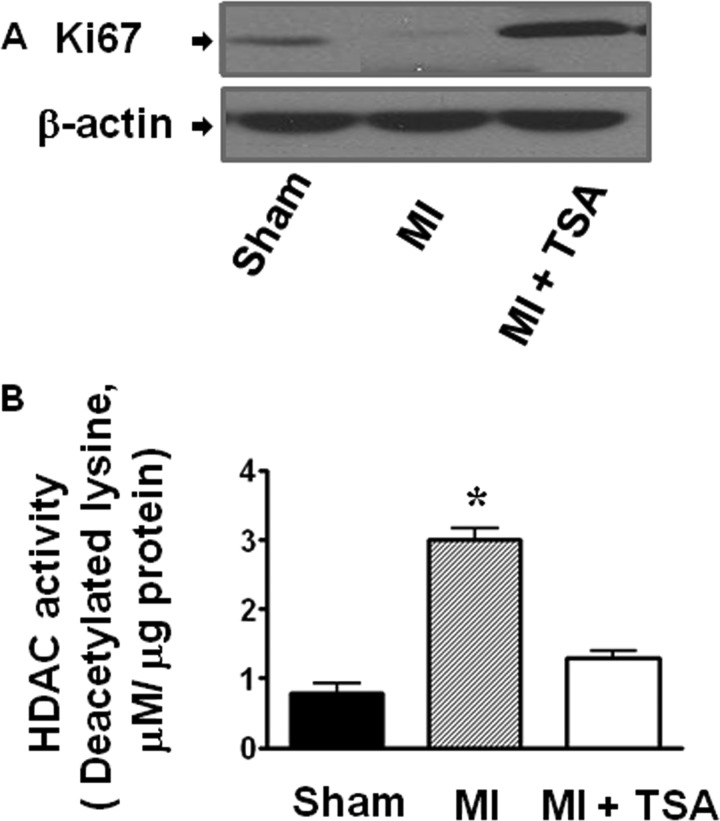

HDAC Inhibition Increases Cardiac Proliferation and Endogenous c-kit+ CSCs in MI Hearts in Vivo, Which Is Absent in KitW/KitW-v Mice

In sham animals, there were rare detectable BrdU-positive myocytes. However, myocardial infarction led to an increase in BrdU-positive stained nuclei and myocytes. As shown in Fig. 3, A, B, and F, and supplemental Fig. S3A, with HDAC inhibition there were significantly more BrdU positive nuclei in infarcted Kit+/+ mice (127.0 ± 8.4/mm2) as compared with infarcted KitW/KitW-v mice (37.4 ± 4.0/mm2, p < 0.001). Additionally, following HDAC inhibition, BrdU-positive myocytes in infarcted Kit+/+ mice (55.1 ± 2.9/mm2) increased significantly as compared with TSA-treated infarcted KitW/KitW-v hearts (8.6 ± 4.2/mm2, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in both BrdU-positive nuclei (24.1 ± 1.9/mm2; 30.0 ± 6.0/mm2) and myocytes (2.9 ± 2.0/mm2; 3.4 ± 0.6/mm2) between control Kit+/+ MI and control KitW/KitW-v MI in the absence of TSA treatments, respectively. Furthermore, HDAC inhibition significantly increased the percentage of nuclei that expressed Ki67 in the infarcted Kit+/+ hearts (114.0 ± 9.3/mm2) as compared with KitW/KitW-v MI hearts (28.6 ± 2.4/mm2, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3, C, D, and G, and supplemental Fig. S3B). Likewise, Ki67-positive myocytes in Kit+/+ MI mice increased significantly as compared with KitW/KitW-v MI hearts (24.0 ± 5.3/mm2; 5.0 ± 0.8/mm2, p < 0.001) following HDAC inhibition. However, without TSA treatment there was no significance difference in Ki67 positively stained nuclei (31.0 ± 7.6/mm2; 25.0 ± 3.6/mm2) and myocytes (5.7 ± 1.3/mm2; 4.0 ± 0.5/mm2) between control Kit+/+ MI and control KitW/KitW-v MI, respectively. We observed that with HDAC inhibition, cardiac c-kit+ CSCs increased in Kit+/+ MI hearts as compared with KitW/KitW-v MI hearts (123.0 ± 12.0/mm2; 34.5 ± 4.5/mm2, p < 0.05). There was no significant difference in cardiac c-kit+ CSCs between control infarcted Kit+/+ MI and control KitW/KitW-v groups without TSA treatments (Fig. 3, E and H, and supplemental Fig. S3C). In consistency with the marked elevation of mitosis following HDAC inhibition observed above, protein expressions of Ki67 increased upon HDAC inhibition (Fig. 4A). HDAC activity was significantly inhibited by TSA treatments in MI hearts (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, as shown in supplemental Fig. S4, when TSA-treated c-kit+ CSCs were re-introduced into KitW/KitW-v MI hearts, BrdU, Ki67 positive stained nuclei, myocytes, and c-kit+ CSCs increased significantly as compared with control KitW/KitW-v MI hearts.

FIGURE 3.

HDAC inhibition stimulates endogenous cardiac regeneration after MI. A–E, quantitative analyses of BrdU, Ki67, and c-Kit+ CSC staining in 20 paraffin-embedded sections per heart. Hearts were fixed and sectioned 8 weeks after MI; F–I, representative images from TSA-treated Kit+/+mouse MI and sham hearts. Nuclei were stained in blue (DAPI) and cardiomyocytes in green (α-sarcomeric actinin); BrdU, Ki67, and c-kit were stained in red. α-Sarc Act, α-sarcomeric actinin; Scale bars, 50 μm; the values represent mean ± S.E., ***, p < 0.001 (n = 4–7 hearts/group).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of HDAC inhibition augments the protein expression of Ki67 (A); HDAC activities decreased in Kit+/+ MI hearts that received TSA treatment (B). Values represent mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05 (n = 3/per group).

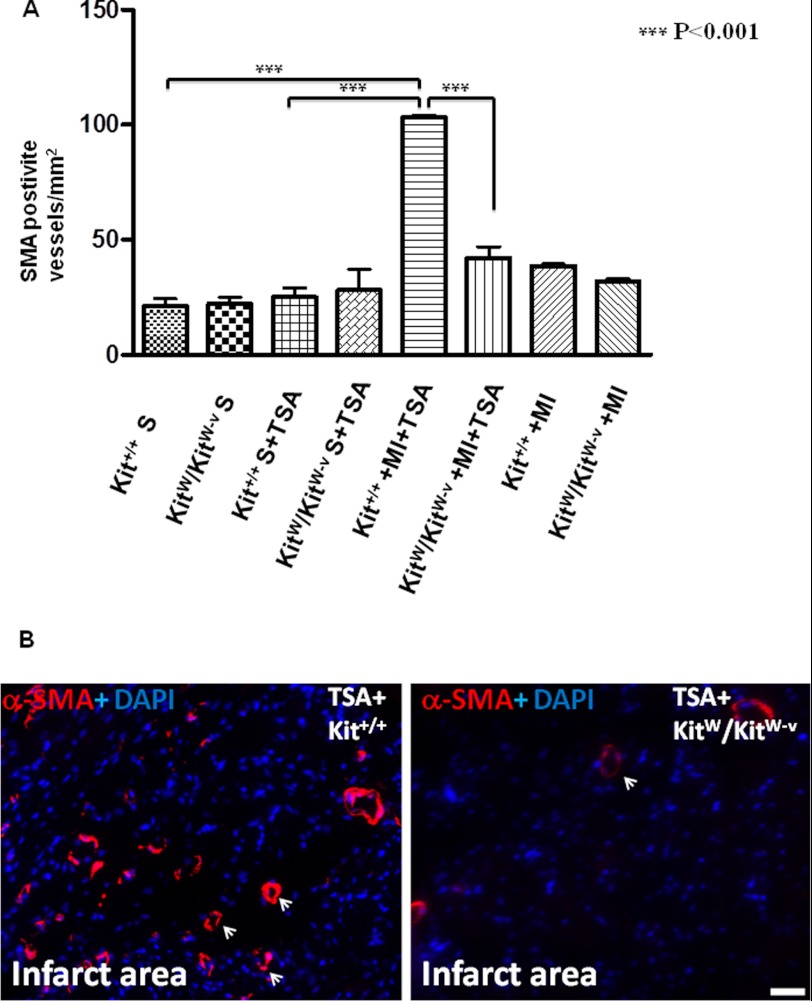

HDAC Inhibition Enhances Neovascularization, Which Is Eliminated in KitW/KitW-v Mice

Angiogenic responses were examined by immunofluorescent staining for α-SMA-positive vessel structures. In the border and center of the infarct zone, α-SMA-positive microvessels were observed. There was no significant difference between control KitW/KitW-v MI and control Kit+/+ MI heart in the absence of TSA treatment (38.9 ± 0.6/mm2; 32.0 ± 0.8/mm2). TSA treatment substantially increased α-SMA positive microvessel densities in Kit+/+ MI hearts (103.0 ± 1.2/mm2) (Fig. 5, A and B). However, the formation of α-SMA-positive microvessels induced by TSA were remarkably decreased in KitW/KitW-v mice (42.0 ± 4.9/mm2, p < 0.001), indicating that disruption of c-kit signaling abrogated angiogenesis induced by HDAC inhibition. Also, when TSA-treated c-kit+ CSCs were re-introduced into KitW/KitW-v MI hearts, the formation of α-SMA-positive microvessels increased to a degree that occurred in infarcted KitW/KitW-v animals that were treated with TSA and were significantly higher than the control KitW/KitW-v MI group (supplemental Fig. S4).

FIGURE 5.

HDAC inhibition-induced angiogenesis diminishes in KitW/KitW-v MI mice. A, quantitative analysis of microvessel formation in MI hearts from Kit+/+mice and KitW/KitW-v mice. B, representative images of newly formed α-SMA-positive microvessels in Kit+/+mice and KitW/KitW-v MI hearts that received TSA treatment. α-SMA-positive microvessels were stained in red and nuclei in blue. Scale bars, 50 μm; the values represent mean ± S.E., ***, p < 0.001 (n = 4–7 hearts/group).

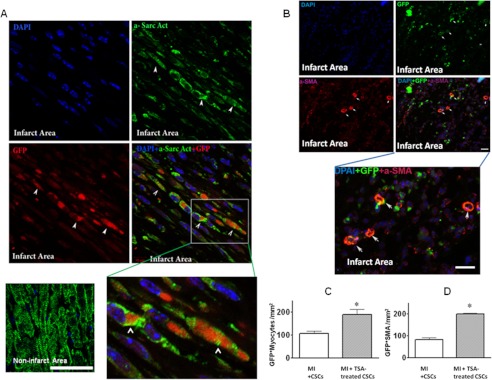

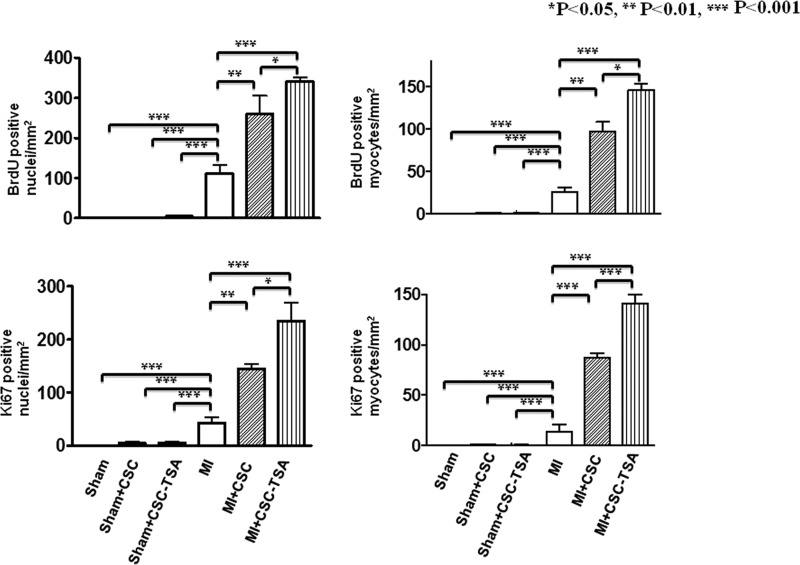

Preconditioning c-kit+ CSCs with TSA Augments Myocardial Repair in CSC-engrafted MI Hearts

We next sought to test whether preconditioning of c-kit+ CSCs via HDAC inhibition would enhance the c-kit+ CSC-derived regenerated myocardium in the c-kit+ CSC-engrafted MI heart. To track the fate of transplanted c-kit+ CSCs, we established the GFP-positive stable c-kit+ CSCs using the standard G418 selective method. Sham animals receiving c-kit+ CSCs in the presence/absence of TSA did not show newly formed myocyte structure. Notably, the newly formed myocytes and α-SMA-positive microvessels derived from GFP+ c-kit+ CSCs were observed in the cell-engrafted MI heart. The hearts engrafted with TSA-treated c-kit+ CSCs showed a significant increase in newly regenerated myocytes and microvessels compared with MI heart-engrafted c-kit+ CSCs only (Fig. 6, A–D). In addition, as shown in Fig. 7, MI hearts receiving TSA-treated c-kit+ CSCs resulted in a marked increase in BrdU-positive nuclei (342 ± 9/mm2) as compared with MI hearts receiving c-kit+ CSCs alone (261 ± 41/mm2) p < 0.05) and BrdU-positive myocytes (146 ± 7/mm2; 91 ± 11/mm2, p < 0.05), respectively. Likewise, there was an increase in Ki67-stained nuclei (235 ± 34/mm2; 145 ± 8/mm2, p < 0.05) and myocytes (141 ± 9/mm2; 87 ± 5/mm2, p < 0.001) in infarcted hearts receiving TSA-treated c-kit+ CSCs as compared with the MI heart receiving c-kit+ CSCs alone. We also noticed that BrdU- and Ki67-positive nuclei and myocytes in MI + c-kit+ CSCs were higher than control infarcted heart without receiving c-kit+ CSCs.

FIGURE 6.

HDAC inhibition enhances myocardial regeneration in c-kit+ CSC engrafted infarcted hearts. The newly formed cardiomyocytes in MI hearts received TSA-treated GFP+ c-kit+ CSCs; cardiomyocytes were stained in green (α-sarcomeric actinin (a-Sarc Act)) and GFP in red (other groups were not shown).

FIGURE 7.

Quantitative analysis of BrdU and Ki67 in TSA-treated c-kit+ CSC-grafted MI hearts. Values represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 (n = 4/group).

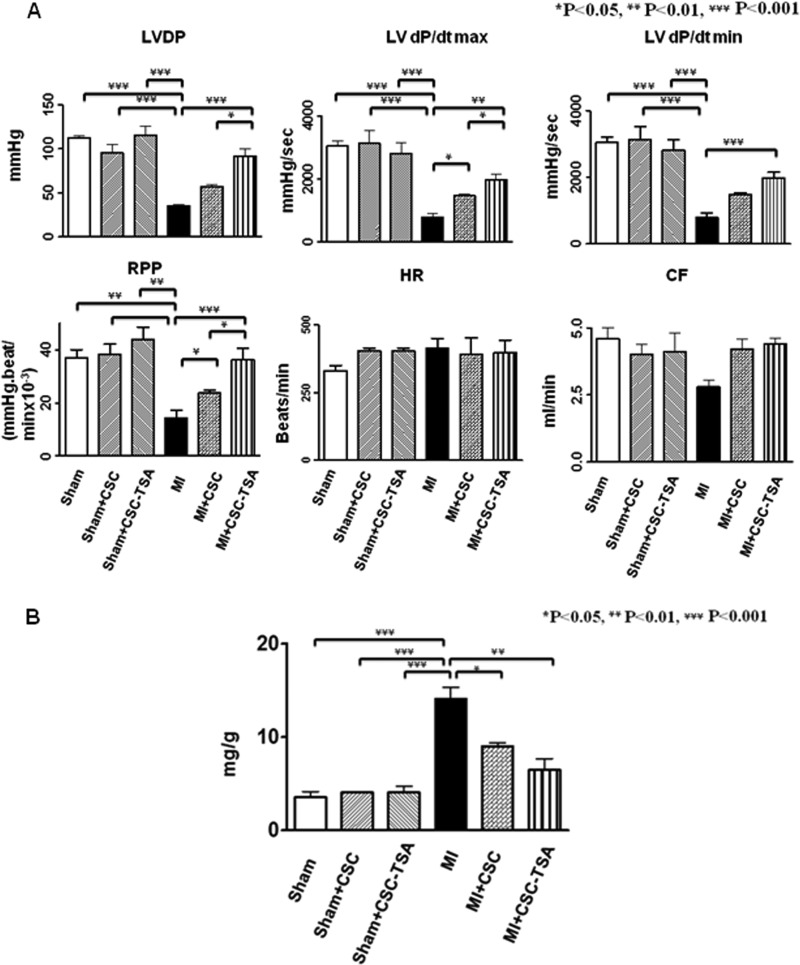

Preconditioning c-kit+ CSCs with TSA Improves Cardiac Functional Recovery in c-kit+ CSC-engrafted MI Hearts

Sham animals receiving c-kit+ CSCs in the presence/absence of TSA did not show differences in ventricular function, suggesting that there is no significant effect of CSCs on sham animals. As shown in Fig. 8A, a significant reduction in left ventricular systolic pressure and developed pressure were observed in infarcted hearts as compared with sham control hearts. MI heart receiving c-kit+ CSCs showed a significant improvement in ventricular functional recovery as compared with control MI hearts. Notably, the engraftment of TSA-treated c-kit+ CSCs into MI hearts improves the LV-dP/dtmax (1998 ± 163 mm Hg/s; 1489 ± 45 mm Hg/s, p < 0.05) to a greater extent than the MI heart receiving c-kit+ CSCs alone. The recovery of LV-dP/dtmin (2024 ± 138 mm Hg/s) in hearts receiving TSA-treated CSCs was also higher than hearts treated with CSCs only (1458 ± 50 mm Hg/s), although it did not reach significant difference. Likewise, the animal receiving TSA-treated CSCs demonstrated the better recovery in left ventricular developed pressure (92 ± 8 mm Hg; 57 ± 2.5 mm Hg, p < 0.05) and rate pressure product (36.2 ± 4.5 × 103 mm Hg/min; 23.9 ± 1.2 × 103 mm Hg/min, p < 0.05). In addition, engraftment of c-kit+ CSCs significantly improved myocardial functional recovery as compared with control MI hearts in which ventricular function included LV-dP/dtmax, LV-dP/dtmin, LV developed pressure, and rate pressure products. MI resulted in the increase in heart/body ratio, which was reduced in c-kit+ CSC-engrafted MI hearts. However, hearts receiving TSA-treated c-kit+ CSCs had a decreased heart/body ratio, although it did not cause a significant difference (Fig. 8B). The results further indicate that preconditioning of c-kit+ CSCs via HDAC inhibition effectively improves myocardial functional recovery in c-kit+ CSC-engrafted MI hearts.

FIGURE 8.

A, HDAC inhibition improves myocardial functional recovery in c-kit+ CSC-engrafted hearts. Measured parameters, including LVDP, heart rate (HR), RPP, LV dP/dtmax, and dP/dtmin, were continuously recorded. Coronary effluent (CF) is in ml/min. B, HDAC inhibition prevents myocardial hypertrophy in c-kit+ CSC-grafted MI hearts. Values represent mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 (n = 4–5/group).

DISCUSSION

Salient Findings

In this study, we demonstrated the following. 1) HDAC inhibition-induced myocardial functional improvement and anti-hypertrophic effect were eliminated by genetic mutation of c-kit in KitW/KitW-v mice. 2) Disruption of c-kit abrogated myocardial repair and neovascularization induced by HDAC inhibition and exacerbated myocardial remodeling in MI hearts. 3) Re-introduction of TSA-treated wild type c-kit+ CSCs into KitW/KitW-v MI heart restored myocardial functional improvement and cardiac repair. 4) Preconditioning of c-kit+ CSCs with TSA increased the formations of new myocytes and microvessels when reintroduced into infarcted hearts. 5) Engraftment of preconditioned c-kit+ CSCs via HDAC inhibition resulted in a significant improvement in myocardial functional recovery.

Even though transplantation of stem cells has extensively been performed for tissue regeneration, these strategies are susceptible to immunological rejection (28). Generating functional cardiac myocytes and new microvessels from stimulating in situ the intrinsic resident CSCs appears to be an important strategy, which could elicit immediate repair in acute myocardial infarction. Recent observations from our laboratory show that HDAC inhibition increased c-kit+ CSCs and promoted endogenous angiomyogenesis in MI heart (19). However, the mechanism(s) by which HDAC inhibition induced cardiac repair to preserve myocardial function is not clear. In this study, we provide new evidence to show that disruption of c-kit in KitW/KitW-v mice eliminated cardiac repair via HDAC inhibition, pointing out a cause and effect relationship between HDAC inhibition and c-kit in inducing myocardial repairs.

The c-kit+ CSCs have been identified to reconstitute well differentiated myocardium in infarcted hearts (20, 29). Inhibition of HDAC promoted a dramatic increase in c-kit+ CSCs in the Kit+/+ MI mice but a decrease in KitW/KitW-v mice, suggesting that the reduction of c-kit+ CSCs is directly associated with an impairment of cardiac repair and myocardial function recovery by disruption of c-kit signaling. In addition, HDAC inhibition-induced angiogenic response presented an association with the improvement in coronary effluents in post-MI Kit+/+ animals compared with KitW/KitW-v mice, supporting that angiogenic response is dependent upon c-kit. It is likely that the increase in angiogenic response in TSA-treated infarcted hearts contributes to the improvement in contractile performance in our studies. It was reported that bone marrow-derived stem cells mobilize to the infarcted area after injury (30). Homing of c-kit-positive cells from bone marrow or transplantation of c-kit+ cells into infarcted hearts was also reported to attribute to myocardial protection and an increase in angiogenesis (31–32). Earlier investigations showed that KitW/KitW-v c-kit mutant mice developed severe myocardial dilation attributable to infarct expansion in a short term of myocardial infarction (16, 17). Transplantation of wild type bone marrow cells into mutant mice rescued the efficient establishment of vessel-rich repair tissue, addressing that c-kit+ cells in bone marrow cells contribute to cardiac repair in a short time MI model. However, we employed an 8-week myocardial infarction model in both Kit+/+ and KitW/KitW-v c-kit mutant mice. There is no significant difference in magnitude in myocardial repair and myocardial functional recovery in the absence of HDAC inhibition. This suggests that c-kit+ cells in bone marrow may not be a major factor involved in myocardial repair via HDAC inhibition in the long term for myocardial infarction. In addition, we also showed that there was no significant change in peripheral c-kit+ stem cell population in the blood after HDAC inhibition (data not shown), but there was a dramatic increase in cardiac c-kit+ CSCs at 8 weeks after MI, indicating that cardiac c-kit+ CSCs rather than peripheral c-kit+ cells contribute mostly to the increased amount of c-kit+ stem cells in the infarcted hearts after HDAC inhibition. It is also very interesting in the future to elucidate whether specific stem cell types differently mediate cardiac repairs and functional recovery at different times after infarction (long term versus short term MI).

Our observations indicate that at the basal condition, sham animals receiving TSA did not exhibit a noticeable change in cardiac function. However, in infarcted hearts, the administration of TSA in KitW/KitW-v mice showed a lack of improvement in cardiac functional recovery, which is associated with reduction of c-kit+ CSCs, pointing out that HDAC inhibition-induced myocardial repair and functional improvement require c-kit+ CSCs. Furthermore, the decrease in myocardial proliferation in KitW/KitW-v MI mice after HDAC inhibition further addresses the dependence of HDAC inhibition on c-kit signaling to induce cardiac repair. Interestingly, transplantation of TSA-treated c-kit+ CSCs into KitW/KitW-v MI mice could restore cardiac functional improvements, reverse remodeling, and enhance cardiac repair, confirming the evident importance of c-kit signaling in this event. In addition, at the basal level, myocardial proliferations were rarely detectable in sham animals in the presence/absence of TSA treatment.

Preconditioning of c-kit+ CSCs via HDAC inhibition resulted in increases in c-kit+ CSC-derived myocardial regeneration, angiogenesis, and improvement of cardiac functional recovery in c-kit+ CSC-engrafted MI hearts, further validating the role of HDAC inhibition in mediating c-kit+ CSCs to induce cardiac repair. We also noticed that sham animals, when receiving c-kit+ CSC engraftment in the presence/absence of TSA treatments, did not demonstrate the newly formed myocyte-like structures. This might suggest that cardiac injury was needed to stimulate the tissue repair when cell engraftments were provided. However, a specific signaling pathway for HDAC inhibition to drive myocardial regeneration still needs to be determined. We have recently found that disruption of NF-κB of c-kit+ CSCs eliminates HDAC inhibition-induced cardiogenesis.3 It will be interesting in the future to evaluate whether NF-κB is also involved in c-kit+ CSC-derived myocardial repair by HDAC inhibition in vivo. In addition, it will be interesting to see whether HDAC inhibition also regulates cardiomyocytes and other cardiac stem cells, which contribute to myocardial repair.

Conclusion

In this study, our results indicate that genetic disruption of c-kit in KitW/KitW-v mice abolished the effect of HDAC inhibition-induced myocardial repair, subsequently blocked the restoration of ventricular functional improvements, and prevented cardiac remodeling. In addition, HDAC inhibition promoted neovascularization in the infarcted myocardium, which was absent in KitW/KitW-v mice. Preconditioning of c-kit+ CSCs via HDAC inhibition enhanced c-kit+ CSC-derived myocardial repair and functional improvements in c-kit+ CSC-engrafted MI heart. The evidence suggests that HDAC inhibition induces myocardial repair and neovascularization through functional c-kit. Our study not only provides new insight into our understanding of mechanism(s) of myocardial repair but also holds great promise to developing a potential clinical strategy for heart diseases.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 HL089405 from NHLBI. This work was also supported by American Heart Association-National Center, Grant 0735458N (to T. C. Z.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

T. C. Zhao, X. Qin, and Y. Zhao, unpublished data.

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase

- MI

- myocardial infarction

- TSA

- trichostatin A

- CSC

- cardiac stem cell

- LV

- left ventricular

- LVDP

- left ventricular developed pressure

- LV dP/dtmax

- left ventricular dP/dtmax

- LV dP/dtmin

- left ventricular dP/dtmin

- RPP

- rate pressure product

- α-SMA

- α-smooth muscle actin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Verdin E., Dequiedt F., Kasler H. G. (2003) Class II histone deacetylases. Versatile regulators. Trends Genet. 19, 286–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vigushin D. M., Coombes R. C. (2004) Targeted histone deacetylase inhibition for cancer therapy. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 4, 205–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheung P., Allis C. D., Sassone-Corsi P. (2000) Signaling to chromatin through histone modifications. Cell 103, 263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hansen J. C., Tse C., Wolffe A. P. (1998) Structure and function of the core histone N termini. More than meets the eye. Biochemistry 37, 17637–17641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luger K., Mäder A. W., Richmond R. K., Sargent D. F., Richmond T. J. (1997) Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature 389, 251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Strahl B. D., Allis C. D. (2000) The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403, 41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turner B. M. (2000) Histone acetylation and an epigenetic code. BioEssays 22, 836–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Antos C. L., McKinsey T. A., Dreitz M., Hollingsworth L. M., Zhang C. L., Schreiber K., Rindt H., Gorczynski R. J., Olson E. N. (2003) Dose-dependent blockade to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by histone deacetylase inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28930–28937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kee H. J., Sohn I. S., Nam K. I., Park J. E., Qian Y. R., Yin Z., Ahn Y., Jeong M. H., Bang Y. J., Kim N., Kim J. K., Kim K. K., Epstein J. A., Kook H. (2006) Inhibition of histone deacetylation blocks cardiac hypertrophy induced by angiotensin II infusion and aortic banding. Circulation 113, 51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kong Y., Tannous P., Lu G., Berenji K., Rothermel B. A., Olson E. N., Hill J. A. (2006) Suppression of class I and II histone deacetylases blunts pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation 113, 2579-2588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Granger A., Abdullah I., Huebner F., Stout A., Wang T., Huebner T., Epstein J. A., Gruber P. J. (2008) Histone deacetylase inhibition reduces myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. FASEB J. 22, 3549–3560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee T. M., Lin M. S., Chang N. C. (2007) Inhibition of histone deacetylase on ventricular remodeling in infarcted rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 293, H968–H977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao T. C., Cheng G., Zhang L. X., Tseng Y. T., Padbury J. F. (2007) Inhibition of histone deacetylases triggers pharmacologic preconditioning effects against myocardial ischemic injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 76, 473–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhao T. C., Zhang L. X., Cheng G., Liu J. T. (2010) gp-91 mediates histone deacetylase inhibition-induced cardioprotection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803, 872–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang L. X., Zhao Y., Cheng G., Guo T. L., Chin Y. E., Liu P. Y., Zhao T. C. (2010) Targeted deletion of NF-κB p50 diminishes the cardioprotection of histone deacetylase inhibition. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 298, H2154–H2163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cimini M., Fazel S., Zhuo S., Xaymardan M., Fujii H., Weisel R. D., Li R. K. (2007) c-kit dysfunction impairs myocardial healing after infarction. Circulation 116, I77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ayach B. B., Yoshimitsu M., Dawood F., Sun M., Arab S., Chen M., Higuchi K., Siatskas C., Lee P., Lim H., Zhang J., Cukerman E., Stanford W. L., Medin J. A. (2006) Stem cell factor receptor induces progenitor and natural killer cell-mediated cardiac survival and repair after myocardial infarction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 2304–2309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Limana F., Germani A., Zacheo A., Kajstura J., Di Carlo A., Borsellino G., Leoni O., Palumbo R., Battistini L., Rastaldo R., Müller S., Pompilio G., Anversa P., Bianchi M. E., Capogrossi M. C. (2005) Exogenous high mobility group box 1 protein induces myocardial regeneration after infarction via enhanced cardiac C-kit+ cell proliferation and differentiation. Circ. Res. 97, e73–e83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang L., Qin X., Zhao Y., Fast L., Zhuang S., Liu P., Cheng G., Zhao T. C. (2012) Inhibition of histone deacetylases preserves myocardial performance and prevents cardiac remodeling through stimulation of endogenous angiomyogenesis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 341, 285–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beltrami A. P., Barlucchi L., Torella D., Baker M., Limana F., Chimenti S., Kasahara H., Rota M., Musso E., Urbanek K., Leri A., Kajstura J., Nadal-Ginard B., Anversa P. (2003) Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell 114, 763–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laugwitz K. L., Moretti A., Lam J., Gruber P., Chen Y., Woodard S., Lin L. Z., Cai C. L., Lu M. M., Reth M., Platoshyn O., Yuan J. X., Evans S., Chien K. R. (2005) Postnatal isl1+ cardioblasts enter fully differentiated cardiomyocyte lineages. Nature 433, 647–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pfister O., Mouquet F., Jain M., Summer R., Helmes M., Fine A., Colucci W. S., Liao R. (2005) CD31− but Not CD31+ cardiac side population cells exhibit functional cardiomyogenic differentiation. Circ. Res. 97, 52–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oh H., Bradfute S. B., Gallardo T. D., Nakamura T., Gaussin V., Mishina Y., Pocius J., Michael L. H., Behringer R. R., Garry D. J., Entman M. L., Schneider M. D. (2003) Cardiac progenitor cells from adult myocardium. Homing, differentiation, and fusion after infarction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 12313–12318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smart N., Bollini S., Dubé K. N., Vieira J. M., Zhou B., Davidson S., Yellon D., Riegler J., Price A. N., Lythgoe M. F., Pu W. T., Riley P. R. (2011) De novo cardiomyocytes from within the activated adult heart after injury. Nature 474, 640–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ellison G. M., Torella D., Dellegrottaglie S., Perez-Martinez C., Perez de Prado A., Vicinanza C., Purushothaman S., Galuppo V., Iaconetti C., Waring C. D., Smith A., Torella M., Cuellas Ramon C., Gonzalo-Orden J. M., Agosti V., Indolfi C., Galiñanes M., Fernandez-Vazquez F., Nadal-Ginard B. (2011) Endogenous cardiac stem cell activation by insulin-like growth factor-1/hepatocyte growth factor intracoronary injection fosters survival and regeneration of the infarcted pig heart. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 58, 977–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tseng A., Stabila J., McGonnigal B., Yano N., Yang M. J., Tseng Y. T., Davol P. A., Lum L. G., Padbury J. F., Zhao T. C. (2010) Effect of disruption of Akt-1 of lin(−)c-kit(+) stem cells on myocardial performance in infarcted heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 87, 704–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheng K., Li T. S., Malliaras K., Davis D. R., Zhang Y., Marbán E. (2010) Magnetic targeting enhances engraftment and functional benefit of iron-labeled cardiosphere-derived cells in myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 106, 1570–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Swijnenburg R. J., Schrepfer S., Govaert J. A., Cao F., Ransohoff K., Sheikh A. Y., Haddad M., Connolly A. J., Davis M. M., Robbins R. C., Wu J. C. (2008) Immunosuppressive therapy mitigates immunological rejection of human embryonic stem cell xenografts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12991–12996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fransioli J., Bailey B., Gude N. A., Cottage C. T., Muraski J. A., Emmanuel G., Wu W., Alvarez R., Rubio M., Ottolenghi S., Schaefer E., Sussman M. A. (2008) Evolution of the c-kit-positive cell response to pathological challenge in the myocardium. Stem Cells 26, 1315–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Orlic D., Kajstura J., Chimenti S., Limana F., Jakoniuk I., Quaini F., Nadal-Ginard B., Bodine D. M., Leri A., Anversa P. (2001) Mobilized bone marrow cells repair the infarcted heart, improving function and survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 10344–10349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fazel S., Cimini M., Chen L., Li S., Angoulvant D., Fedak P., Verma S., Weisel R. D., Keating A., Li R. K. (2006) Cardioprotective c-kit+ cells are from the bone marrow and regulate the myocardial balance of angiogenic cytokines. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 1865–1877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jackson K. A., Majka S. M., Wang H., Pocius J., Hartley C. J., Majesky M. W., Entman M. L., Michael L. H., Hirschi K. K., Goodell M. A. (2001) Regeneration of ischemic cardiac muscle and vascular endothelium by adult stem cells. J. Clin. Invest. 107, 1395–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.