Abstract

The mangrove rivulus (Kryptolebias marmoratus) is an excellent model species for understanding the physiological mechanisms that fish use in coping with extreme environmental conditions, particularly cutaneous exchange during prolonged exposure to air. Their ability to self-fertilize and produce highly homozygous lineages provides the potential for examining environmental influences on structures and related functions without the complications of genetic variation. Over the past 10 years or so, we have gained a broader understanding of the mechanisms K. marmoratus use to maintain homeostasis when out of water for days to weeks. Gaseous exchange occurs across the skin, as dramatic remodeling of the gill reduces its effective surface area for exchange. Ionoregulation and osmoregulation are maintained in air by exchanging Na+, Cl−, and H2O across skin that contains a rich population of ionocytes. Ammonia excretion occurs in part by cutaneous NH3 volatilization facilitated by ammonia transporters on the surface of the epidermis. Finally, new evidence indicates that cutaneous angiogenesis occurs when K. marmoratus are emersed for a week, suggesting a higher rate of blood flow to surface vessels. Taken together, these and other findings demonstrate that the skin of K. marmoratus takes on all the major functions attributed to fish gills, allowing them to move between aquatic and terrestrial environments with ease. Future studies should focus on variation in response to environmental changes between homozygous lineages to identify the genetic underpinnings of physiological responses.

Introduction

The environment, whether aquatic or terrestrial, has had a large impact on the evolution of structure and function in animals. If one considers respiratory structures, for example, breathing water is challenging because it is 800 times more dense, 60 times more viscous, and contains 30 times less oxygen relative to air (Dejours 1988). Consequently, gills in extant fishes are highly efficient at extracting oxygen. Air breathers can breathe fewer breaths relative to water breathers to take up the same amount of oxygen (Dejours 1974). However, the greatest challenge for air breathers is dehydration. Over evolutionary time, the benefits of breathing air must have outweighed the costs because more than 370 species of air-breathing fish are known (Graham 1997). So what’s so special about Kryptolebias marmoratus—is it just one of many or is it a remarkable species that can provide us with novel insights into the physiology of breathing air? I will argue the latter for three key reasons: (1) these fish are self-fertilizing, (2) tolerant of extreme environments, and (3) they completely rely on cutaneous respiration when out of water.

Self-fertilization

K. marmoratus are self-fertilizing hermaphrodites (Harrington 1961; Tatarenkov et al. 2009) and produce highly homozygous lineages when isolated in the laboratory for many generations (Vrijenhoek 1985; Turner et al. 1990). Wild populations are androdioecious; males occur at low, but variable, rates and outcrossing between males and hermaphrodites is thought to be the cause of heterozygosity (see Tatarenkov this issue). For physiologists interested in the effects of environment on the phenotype (e.g. structure, function), the ability to study isogenic laboratory strains eliminates the confounding factor of genotype. Further, if differences in physiological responses to environmental change are detected between isogenic strains and between wild populations, then a more detailed differential genetic screening may provide new insights into regulatory pathways. For example, acclimation to changing environmental salinity is variable among lineages of K. marmoratus. We have discovered that in hypersaline water, some lineages remodel their gills and decrease the effective surface area for exchange, presumably limiting excessive ion uptake (discussed below), whereas other lineages show no response (A. Turko and P. Wright, unpublished data). If the gene and/or protein expression profiles of the gills from lineages showing a differential response to salinity are compared, then the genes and proteins responsible for regulating remodeling of the gills could be identified. In addition, comparing plasma hormone profiles among those fish that do undergo changes in the gills and those that do not would be one step toward understanding whether gill remodeling in response to salinity is under endocrine control. A comparative genomics approach has been used in euryhaline Fundulus sp. to identify the importance of particular genes in acclimation to salinity and in physiological systems that may be linked to osmotic tolerance and niche segregation (Whitehead 2012).

To date, physiologists have not capitalized on this opportunity in K. marmoratus. Significant progress has been made in understanding the genetics of K. marmoratus (see Tararenkov this issue) and the annotated genome of multiple lineages is soon to be available (see Kelly this issue). In addition, identifying phenotypic differences in growth and behavior between isogenic lineages (see Earley this issue) is valuable information when assessing which lineages are most suited for specific environmental manipulations. Thus, in the next few years, there is potential for great gains and novel insights to be made in determining the factors controlling physiological responses to environmental change using K. marmoratus as a model species.

Extremophilic

The second reason why K. marmoratus are of particular physiological interest is that they thrive under relatively extreme conditions. Physiologists interested in understanding the underlying mechanisms of a response to the environment may gain more information from an animal that is surviving at the limits of tolerance rather than an organism that tolerates only moderate conditions. Textbooks of comparative animal physiology routinely present this tenet in their opening pages as the August Krogh Principle “For every well-defined physiological problem there is an animal optimally suited to yield an answer” (Randall et al. 2002). For example, if one is interested in the physiological consequences of air-breathing in fish, more insight may be gained from studying K. marmoratus that survives for ∼2 months out of water (emersed) compared with a species that gulps air occasionally at the surface of the water.

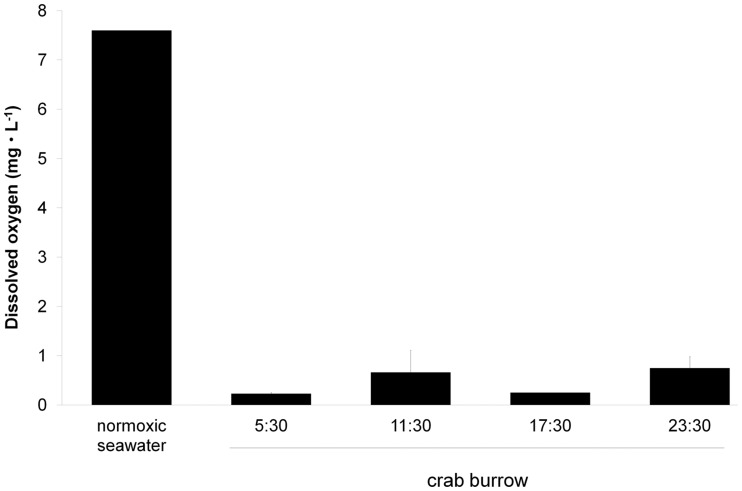

The extreme nature of the habitat of K. marmoratus is readily apparent by taking a walk through the mangrove forests of the western Atlantic region (Taylor et al. 1995; see also Taylor this issue). Progress is slow as you climb over a tangle of aerial roots from the red mangrove trees and sink deep into the thick mud where microbial activity releases malodorous hydrogen sulphide from deep layers of decaying vegetation. K. marmoratus typically reside in crab burrows (8.0 ± 0.5 cm [diameter] × 33.9 ± 2.0 cm [long], n = 13) (P. Wright and D.S. Taylor, unpublished data) on the forest floor. Water quality for aquatic respiration in these crab burrows could not be worse—the water is extremely hypoxic (Fig. 1), has elevated levels of H2S (Abel et al. 1987), and is warm (25–30°C) (Davis et al. 1990; Taylor 2000; Frick and Wright 2002a). We measured dissolved oxygen (DO) levels in crab burrows where K. marmoratus were found on Calabash Caye in December 2009 over a 24-h period (Fig. 1; see also Ellison et al. 2012). Normally, fully air-saturated water at these temperatures and salinity would contain ∼7.5 mg L−1 DO; however, mean DO in the crab burrows was <1 mg L−1, a level of oxygen few aquatic species tolerate for long. Earlier studies on K. marmoratus reported that the fish were insensitive to hypoxia alone but emersed when exposed to a combination of elevated H2S (0.003 mg L−1) and mild hypoxia (2 mg L−1 DO) (Abel et al. 1987). Obviously K. marmoratus are tolerant of extreme water conditions, but emersion may be a convenient escape when environmental conditions are beyond the range of tolerance.

Fig. 1.

DO levels in three neighboring crab burrows (site 1) on Calabash Caye, Belize, at the end of the wet season (December 2009) over a 24-h period. Note that fully oxygenated water (28°C, 38‰) would have a DO level of ∼7.5 mg L−1 (P. Wright et al., unpublished data). Means ± S.E. (n = 3).

Using a remote video camera, we recorded activity at the surface of a crab burrow in Calabash Caye, Belize (see Supplementary Video). Several mangrove rivulus were observed resting on a small branch at the air–water interface. At the same time, the crab Cardisoma guanhumi rose to the surface from deep within the burrow and aerated its gills. No doubt aerial respiration for both animals is a routine and possibly necessary daily behavior due to the severely hypoxic water in which they reside. To our knowledge, there have been no studies quantifying the amount of time K. marmoratus remains immersed in crab burrows under these conditions. This information would be valuable to assess their tolerance to hypoxia (and H2S) in the field.

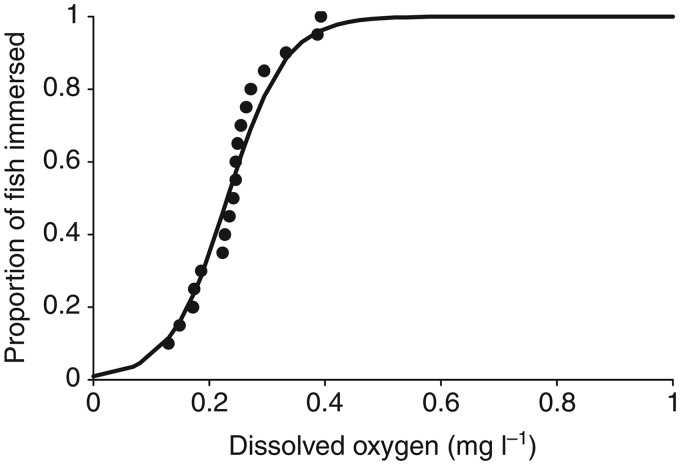

We decided to examine the emersion response in more detail in the laboratory to carefully quantify the threshold for breathing air in response to hypoxia. When the oxygen content of water was acutely lowered from normoxia to hypoxia, 50% of K. marmoratus emersed at 0.23 mg L−1 DO (Fig. 2) (Regan et al. 2011), an O2 level similar to that in water in burrows (Fig. 1). These results demonstrate that hypoxia alone induces emersion, in contrast to the findings of Abel et al. (1987). The level of hypoxia used by Abel et al. (2 mg L−1 DO) was well above the threshold for emersion (<0.4 mg L−1 DO) found in the study by Regan et al. (2011). In most air-breathing fish, hypoxia induces air-breathing at higher levels of DO relative to K. marmoratus and full emersion is typically unnecessary (Graham 1997; Chapman and McKenzie 2009). Before emersion, K. marmoratus appear to spend more time at the surface, but a careful study to characterize aquatic surface respiration (ASR) has not been conducted for this species. ASR is a common behavior in hypoxia-tolerant fish when oxygen is depleted from deeper waters (Chapman and McKenzie 2009). What mechanisms enable K. marmoratus to tolerate extreme hypoxia? The answer is unknown. In fish, the short-term critical adjustment to lower levels of oxygen in the water that limit the mismatch between demand and supply of oxygen is the hypoxia ventilatory response (HVR) (Perry et al. 2009). The HVR involves an increase in the rate of ventilation and/or the volume of water pumped over the gills per breath. Mangrove rivulus have a robust HVR, increasing mostly the rate of ventilation rather than the ventilatory amplitude when water DO is lowered to 3–5 mg L−1 (A. Turko et al., submitted for publication). It is also adaptive if fish can increase the rate of perfusion through cardiovascular adjustments during exposure to hypoxia, but there are no data in this regard with respect to K. marmoratus. Longer term resistance to hypoxia in animals has been linked to the hypoxia inducible factor (HIF-1α), a transcription factor that controls the expression of numerous genes controlling angiogenesis, formation of red blood cells, glycolysis, and other pathways (reviewed by Nikinmaa and Rees 2005). Increased hemoglobin levels or changes in the expression of hemoglobin isoforms toward higher-affinity isomorphs have been reported (Frey et al. 1998; Rutjes et al. 2007; Campo et al. 2008; Wells 2009), but, again, whether similar adjustments occur in K. marmoratus is unknown. Investigations of HIF-1α expression and downstream effects in response to hypoxia in K. marmoratus are warranted.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of K. marmoratus immersed in water at low levels of DO (DO; mg L−1). At lower DO levels (<0.4 mg L−1), fish emersed and adhered to the side of the experimental chamber (N = 21, EC50 = 0.23 mg L−1 DO). From Regan et al. (2011).

Respiration in air

The third advantage of studying K. marmoratus is that the mechanisms of cutaneous exchange in air-breathing fishes are not completely understood. Cutaneous respiration is not uncommon in amphibious fishes (Graham 1997; Sayer 2005), but few depend on the skin as the sole site of exchange like K. marmoratus does without accessory air-breathing organs (ABOs). To maintain homeostasis in air, fish must continue to transport O2 and CO2, balance ions and water, and prevent the accumulation of potentially toxic nitrogenous wastes. There is a vast body of literature on the structure of ABOs and the respiratory/cardiovascular changes that occur when air-breathing fishes switch from aquatic to aerial respiration (see Hughes 1976; Graham 1997). In addition, detailed work has been carried out more recently on various strategies for nitrogen excretion in air-breathing fish (reviewed by Ip et al. 2001; Sayer 2005; Chew et al. 2006). However, many questions remain. If cutaneous respiration dominates during emersion, does the structure and function of the skin and gills reversibly remodel to accommodate changing roles on land? Over the past decade, researchers in my laboratory have focused on mechanisms responsible for cutaneous exchange and tissue remodeling when K. marmoratus emerse. Highlights from this and other work are reviewed below.

Morphological plasticity of gills

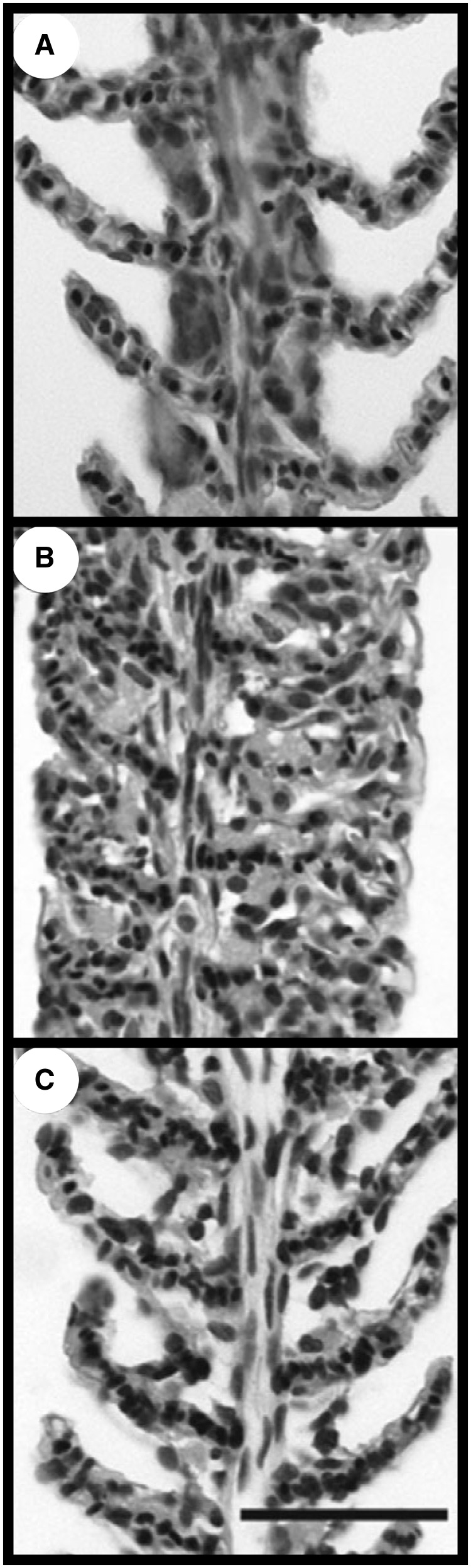

For most fish, the gills are the primary site of exchange between the external environment and the blood (internal environment). Gaseous exchange, excretion of nitrogenous wastes, acid–base regulation, and osmoregulation and ionoregulation occur at the gills (Evans et al. 2005), with the cutaneous surface and kidneys playing a minor role in most cases. In the absence of water, gill lamellae (also called secondary lamellae) collapse due to high surface tension, coalesce, and the fused structures reduce the effective surface area for exchange, with irreversible loss of function in most fish (Lam et al. 2006). K. marmoratus may spend minutes to weeks out of water, but gross morphology of the gill when fish are in water (immersed) is typical of other fully aquatic teleosts (Ong et al. 2007). There is no evidence of gill rods, fused lamellae, or widely spaced lamellae typical of some air-breathing fish, such as the mudskipper that partially uses the gills for gaseous exchange in air (e.g. Low et al. 1988; Lam et al. 2006). Also, K. marmoratus do not gulp air or ventilate the opercular chamber when out of water (LeBlanc et al. 2010). Instead, K. marmoratus reversibly remodel their gills in response to exposure to air. A cell mass appears between the lamellae (interlamellar cell mass [ILCM]) which effectively reduces the gill’s surface area after a week in air; after recovery in water, the ILCM degenerates (Fig. 3; Ong et al. 2007; Turko et al. 2011). Reversible changes in morphology of the gills were first reported in the fully aquatic crucian carp (Carassius carassius) and closely related goldfish (C. auratus) with changes in temperature and in oxygen content of the water, a response that is thought to be effective in balancing oxygen uptake with loss of ions in these freshwater species (Sollid et al. 2003, 2005; Nilsson 2007). The physiological value of reduced surface area of the gills in emersed K. marmoratus is unknown. Remodeling of the gills in K. marmoratus may be a mechanism that decreases the risk of desiccation and/or preserves lamellar structure when K. marmoratus are out of water for extended periods (Ong et al. 2007).

Fig. 3.

Representative light micrographs of gill filaments and lamellae of a control K. marmoratus in water (A), a fish exposed to air for 1 week (B), and a fish recovered in water for 1 week after a week in air (C). Scale bar = 50 µm. From Ong et al. (2007).

Gaseous exchange

Metabolic rate does not typically decline when amphibious fish emerse (e.g. Gordon et al. 1969; Gordon et al. 1978; Steeger and Bridges 1995; Kok et al. 1998; Takeda et al. 1999), although in cases when the habitat dries aestivation is critical for survival (e.g. African lungfish; Janssen 1964). On land, K. marmoratus requires a moist habitat and metabolic rate (as measured by excretion of CO2) is maintained, or even enhanced, over the first 5 days of exposure to air (Ong et al. 2007). Moreover, mitochondrial oxidative enzymes (plus seven enzymes involved in amino acid metabolism) were unchanged or slightly increased in K. marmoratus held for 10 days in air (Frick and Wright 2002b). These data suggest that cutaneous respiration adequately meets the metabolic needs of K. marmoratus at least over the first week or so.

Gaseous exchange may be facilitated during aerial episodes by an increase in cutaneous blood flow. Grizzle and Thiyagarajah (1987) reported that the dorsal epidermis of K. marmoratus contains capillaries within 1 μm of the skin’s surface providing a very short diffusion distance between air and blood. In other amphibious species, estimated diffusion distances are slightly greater and vary considerably (2–340 μm) (e.g. Yokoya and Tamura 1992; Graham 1997; Zhang et al. 2000; Park 2002; Park et al. 2003). In K. marmoratus, arteriole diameter narrows in vessels of the caudel fin within the first 20 seconds of exposure to air (Cooper et al. 2011), a change that would diminish, not enhance, blood flow. The fact that these changes were reversed upon application of the α-adrenoreceptor blocker phentolamine indicates that this initial vasoconstriction was probably a catecholamine-induced response to stress. Long-term acclimation to a terrestrial environment (10 days) induced cutaneous angiogenesis (Cooper et al. 2011). Using immunohistochemistry and the antibody for the endothelial protein CD31 (Baluk and McDonald 2008), we showed an increased CD31 signal in the caudal vessels of air-exposed K. marmoratus (Cooper et al. 2011). These results indicate that the turnover of endothelial cells or the overall number of endothelial cells was increased in air. The fins of K. marmoratus constitute ∼40% of the body’s surface area (Cooper et al. 2011), and therefore if angiogenesis is restricted to the fins only (but may also be occurring across the total surface of the body), then these changes would potentially have a significant impact on the exchange of gas during prolonged terrestrial episodes.

The skin of K. marmoratus appears to play a role in sensing oxygen levels in the environment. In most fish, hypoxia is detected by chemoreceptive neuroepithelial cells (NECs) in the gills (Dunel-Erb et al. 1982; Jonz and Nurse 2003; Saltys et al. 2006). Gill NECs are positioned externally (where they are in contact with the incident flow of water and may detect aquatic hypoxia) or internally (where they respond to changes in oxygen levels of the blood) (Perry et al. 2009). In some air-breathing fish, gill NECs mediate hypoxia-induced air-breathing at the surface (Smatresk 1986; Shingles et al. 2005; Lopes et al. 2010). In K. marmoratus, NECs were found in the gill and over the entire cutaneous surface, occupying the uppermost epithelial layer (Regan et al. 2011). NECs of both the skin and gills increase cell area in response to chronic hypoxia, and pharmacological studies suggest that they may be involved in regulating the response to emersion in K. marmoratus (Regan et al. 2011). Further studies are required to determine whether cutaneous sensing of oxygen is ubiquitous in air-breathing fishes.

Ionoregulation and osmoregulation

As mangrove rivulus move from water onto land, they must maintain homeostasis of water and ions without the use of branchial epithelium and possibly, under some circumstances, in an environment with <100% humidity. Variations in salinity commonly occur in mangroves, both spatially (freshwater or brackish streams flowing over mudflats) and temporally (heavy rainfalls versus dry season) (Gordon et al. 1985). Even when fish leave water, the salinity of the moist substratum would presumably vary depending on these same factors. Given these challenges, K. marmoratus managed to maintain perfect whole-body homeostasis of Cl− and water but not Na+ balance over a 9-day period of exposure to air in the laboratory (LeBlanc et al. 2010).

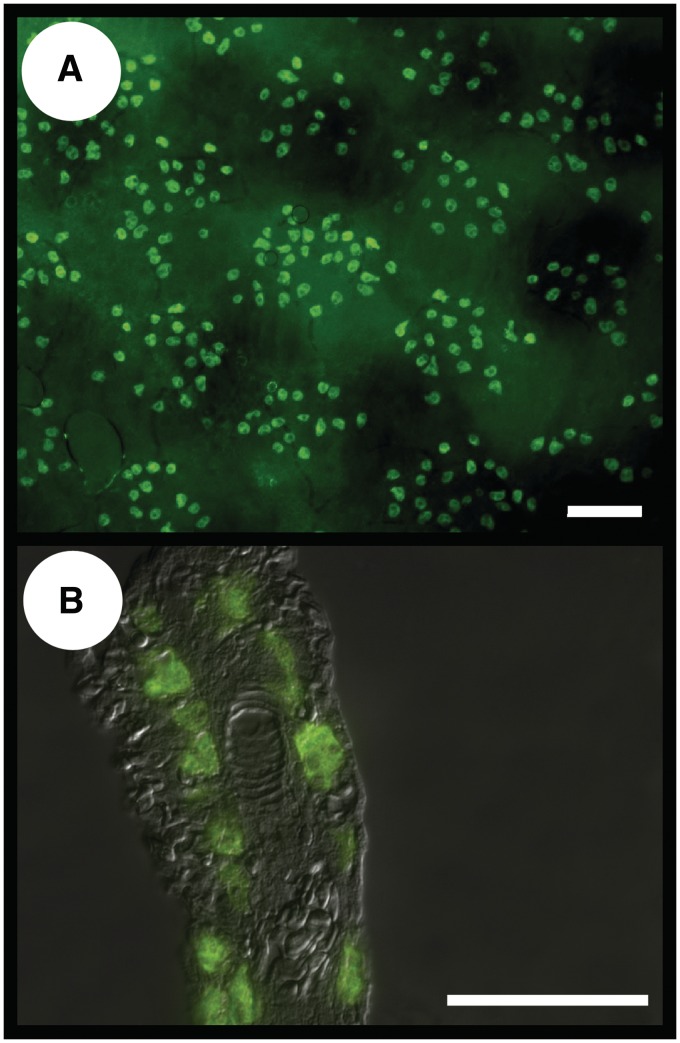

Ion-transporting cells (ionocytes) in the skin have been reported in some amphibious fish but not in others (Schwerdtfeger and Bereiter-Hahn 1978; King et al. 1989; Yokoya and Tamura 1992). In K. marmoratus, a rich population of ionocytes are present on the cutaneous surface (Fig. 4A) as well as on the gills (Fig. 4B). Skin ionocytes form clusters of 20–30 cells and the physiological significance of this pattern is unknown. Is the clustering synchronous with the discontinuous subepidermal scales and/or with the coordinated signaling pathway Delta/Jagged-Notch that regulates cell clustering in zebrafish embryos? (Hsiao et al. 2007; Jänicke et al. 2007) Further studies are required to understand the functional role of these clusters in K. marmoratus.

Fig. 4.

Representative fluorescent images of 2-(4-dimethyl-aminostyryl)-1-ethyl-pyridinium (DASPEI)-stained mitochondrial-rich cells (ionocytes) in the skin (A) of K. marmoratus acclimated to seawater (45‰). The cells form a clustering pattern with 20–30 cells/cluster. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) The antibody to Na+K+ATPase was used to identify ionocytes in the gills of K. marmoratus exposed to air for 9 days over a moist (45‰) surface. The image shows a single filament with no evidence of individual lamellae. The ionocytes are mostly embedded within the mass of cells on the filament and the interlamellar space. Scale bar = 50 µm. From LeBlanc et al. (2010).

Cutaneous ionocytes are probably the key site of ion transport when K. marmoratus are emersed. The surface area of cutaneous ionocytes was larger in air-exposed rivulus in contact with a moist hypersaline (45‰) compared with a freshwater (1‰) surface, suggesting that a larger surface area of cells would be beneficial for ionoregulation at the higher salinity (LeBlanc et al. 2010). The number of mucous cells declined significantly in air-exposed rivulus (45‰ substrate), indicating that increased mucus production in K. marmoratus is probably not a strategy that protects body tissues from dehydration in air, unlike the case for other air-breathing fish (Lam et al. 2006). Do other structural changes occur in the skin that retain body water but exchange critical molecules during prolonged exposure to air? There are many avenues for further investigation.

Volatilization of NH3

Animals catabolize proteins and amino acids for fuel and maintenance/turnover of body proteins, resulting in the synthesis of ammonia (Wright 1995). Ammonia is a neurotoxin and elevated concentrations of ammonia in the tissues are harmful to fish (reviewed by Ip et al. 2001). Ammonia exists in solution as both the dissolved gas NH3 and the ion NH4+, although at physiological pH the equilibrium is shifted toward NH4+ (pKamm ∼ 9). Normally, fish excrete ammonia as NH3 down the gill’s blood-to-water NH3 partial pressure gradient by way of ammonia gas channels, the Rhesus (Rh) glycoproteins (for reviews see Weihrauch et al. 2009; Wright and Wood 2009). Diffusion of ammonia across the gills and its dilution in the aquatic environment prevents its accumulation in the tissues, but elevated environmental levels or exposure to air may prevent efficient elimination of waste nitrogen.

When K. marmoratus are out of water, accumulation of ammonia is avoided by its excretion through alternative routes (see below) or its conversion to less toxic compounds (e.g. urea, glutamine). Urea is a byproduct of arginine catabolism, uric acid degradation, or, in a few unusual cases in fish, the end product of the ornithine urea cycle (OUC) (Anderson 2001). The percent of nitrogen excreted as urea in tropical amphibious fishes varies between 3 and 58% (Graham 1997), with mangrove rivulus excreting 10–40% as urea (Frick and Wright 2002a; Rodela and Wright, 2006a,b). K. marmoratus do not appear to synthesize urea via the OUC because activities of OUC enzymes were relatively low and only modestly increased in response to exposure to air (Frick and Wright 2002b). Thus, urea production in K. marmoratus is likely the result of a combination of arginolysis and uricolysis.

Our work shows that in air, K. marmoratus are one of the rare teleosts that volatilize a significant amount of NH3 from the cutaneous surface (Tsui et al. 2002; Frick and Wright 2002b; Litwiller et al. 2006). An 18-fold increase in NH4+ concentration and a small elevation of pH at the skin’s surface result in a substantial rise in cutaneous partial pressure of NH3 (Litwiller et al. 2006). These changes in the ion composition of the surface of the skin may be related partly to changes in the rate of transport of NH4+/NH3 and H+ (C. Cooper et al., submitted for publication). An induction of Rh glycoproteins Rhcg1 and Rhcg2 mRNA in air may translate into an increase in apical Rhcg proteins in cutaneous ionocytes (Hung et al. 2007; Wright and Wood 2009), facilitating transfer of NH3 to the skin’s surface. Overall, K. marmoratus are highly efficient in eliminating ammonia when emersed because over a 10-day period there was no significant accumulation of whole-body ammonia (Frick and Wright 2002b).

Perspectives and Conclusions

Mangrove rivulus are extremophilic fish that breathe cutaneously when emersed. They are an ideal model species for examining the specific mechanisms of cutaneous exchange that air-breathing fish use to maintain homeostasis over long periods of exposure to air. Our studies have demonstrated that the skin of K. marmoratus shares responsibility for gaseous exchange (Ong et al. 2007; Regan et al. 2011), ionoregulation (LeBlanc et al. 2010), and excretion of nitrogenous wastes (Frick and Wright 2002a; Litwiller et al. 2006; Hung et al. 2007; Wright and Wood 2009) with the gills when immersed but plays a more dominant role when fish emerse. Angiogenesis in the fins could potentially increase blood flow and enhance the capacity for cutaneous exchange in air (Cooper et al. 2011). Moreover, there is a strong potential for further insights into regulatory pathways by identifying differences among strains in responses to environmental perturbations using isogenic lineages of laboratory-reared K. marmoratus.

Funding

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant R15HD070622 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology through the DCE, DCPB, DAB, and the C. Ladd Prosser Fund; and the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Maryland. The NSERC (Canada) Discovery Grants Program has funded the research on K. marmoratus in the Wright laboratory.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data are available at ICB online.

Acknowledgments

I thank my students N. Frick, S. Litwiller, K. Ong, D. LeBlanc, K. Regan, and A. Turko and collaborators Drs. C. Wood, M. O’Donnell, C. Murrant, J. Wilson, D. Fudge, C. Hung, C. Cooper, E.D. Stevens, S. Consuegra, and S. Currie for their contributions to this research. A special thanks to Dr. D. Noakes for introducing me to K. marmoratus in the laboratory and Dr. D.S. Taylor for sharing his passion for the mangroves. I also thank I. Smith, B. Frank, M. Cornish, and Lori Ferguson who provided technical assistance at the University of Guelph. The Calabash Caye field trip in December 2009 included Drs. C. Cooper, S. Consuegra, S. Currie, D.S. Taylor, P. Wright, and graduate students A. Elinson and K. Regan. I am grateful to E. Orlando, B. Ring, and D. Bechler for organizing the Mangrove Killifish symposium.

References

- Abel DC, Koenig CC, Davis WP. Emersion in the mangrove forest fish Rivulus marmoratus: a unique response to hydrogen sulfide. Environ Biol Fishes. 1987;18:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson PM. Urea and glutamine synthesis: environmental influences on nitrogen excretion. In: Wright P, Anderson P, editors. Nitrogen excretion, fish physiology. Vol. 20. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 239–378. [Google Scholar]

- Baluk P, McDonald DM. Markers for microscopic imaging of lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1131:1–12. doi: 10.1196/annals.1413.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo S, Natasi G, D’Ascola A, Campo GM, Avenoso A, Traina P, Calatroni A, Burrascano E, Ferlazzo A, Lupidi G, et al. Hemoglobin system of Sparus aurata: Changes in fishes farmed under extreme conditions. Sci Total Environ. 2008;403:148–53. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman LJ, McKenzie DJ. Behavioural responses and ecological consequences. In: Richards JG, Farrell AP, Brauner CJ, editors. Hypoxia. Fish physiology. Vol. 27. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2009. pp. 26–79. [Google Scholar]

- Chew SF, Wilson JM, Ip YK, Randall DJ. Nitrogen excretion and defense against ammonia toxicity. In: Val AL, Almeida-Val VMF, Randall DJ, editors. The physiology of tropical fishes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 307–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CA, Litwiller SL, Murrant CL, Wright PA. Cutaneous vasoregulation during short- and long-term air exposure in the amphibious mangrove rivulus, Kryptolebias marmoratus. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;161:268–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis WP, Taylor DS, Turner BJ. Field observation of the ecology and habits of mangrove rivulus (Rivulus marmoratus) in Belize and Florida (Teleostei: Cyprinodontiformes: Rivulidae) Ichthyol Explor Freshw. 1990;1:123–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dejours P. Water versus air as the respiratory media. In: Hughes GM, editor. Respiration of amphibious vertebrates. London, UK: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dejours P. Respiration in water and air. New York, NY: Elsevier; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dunel-Erb S, Bailly Y, Laurent P. Neuroepithelial cells in fish gill primary lamellae. J Appl Physiol. 1982;53:1342–53. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.6.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison A, Wright P, Taylor DS, Cooper C, Regan K, Currie S, Consuegra S. Parasites and outcrossing determine the local spatial structure of a mixed-mating vertebrate. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ece3.289. Ecol Evol (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DH, Piermarini PM, Choe KD. The multifunctional fish gill: dominant site of gas exchange, osmoregulation, acid-base regulation and excretion of nitrogenous waste. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:97–177. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00050.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey BJ, Weber RE, van Aardt WJ, Fago A. The haemoglobin system of the mudfish, Labeo capensis: adaptations to temperature and hypoxia. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1998;120B:735–42. [Google Scholar]

- Frick NT, Wright PA. Nitrogen metabolism and excretion in the mangrove killifish Rivulus marmoratus I. The influence of environmental salinity and external ammonia. J Exp Biol. 2002a;205:79–89. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick NT, Wright PA. Nitrogen metabolism and excretion in the mangrove killifish Rivulus marmoratus II. Significant ammonia volatilization in a teleost during air-exposure. J Exp Biol. 2002b;205:91–100. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MS, Boetius I, Evans DH, McCarthy R, Oglesby LC. Aspects of the physiology of terrestrial life in amphibious fishes. I. The mudskipper, Periophthalmus sobrinus. J Exp Biol. 1969;50:141–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MS, Ng WW-S, Yip AY-W. Aspects of the physiology of terrestrial life in amphibious fishes. III. The Chinese mudskipper, Periophthalmus cantonensis. J Exp Biol. 1978;72:57–75. doi: 10.1242/jeb.72.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MS, Gabaldon DJ, Yip AY-W. Exploratory observations on microhabitat selection within the intertidal zone by the Chinese mudskipper fish Periophthalmus cantonensis. Mar Biol. 1985;85:209–15. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JB. Air-breathing fishes; evolution, diversity, and adaptation. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grizzle JM, Thiyagarajah A. Skin histology of Rivulus ocellatus marmoratus: apparent adaptation for aerial respiration. Copeia. 1987;1:237–40. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington RW. Oviparous hermaphroditic fish with internal self-fertilization. Science. 1961;134:1749–50. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3492.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao C-D, You M-S, Guh Y-J, Ma M, Jiang Y-J, Hwang P-P. A positive regulatory loop between foxi3a and foxi3b is essential for specification and differentiation of zebrafish epidermal ionocytes. PLoS One. 2007;2:e302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes GM. Respiration of amphibious vertebrates. London: Academic Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hung CYC, Tsui KNT, Wilson JM, Nawata CM, Wood CM, Wright PA. Rhesus glycoprotein gene expression in the mangrove killifish Kryptolebias marmoratus exposed to elevated environmental ammonia levels and air. J Exp Biol. 2007;210:2419–29. doi: 10.1242/jeb.002568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip YK, Chew SF, Randall DJ. Ammonia toxicity, tolerance and excretion. In: Wright PA, Anderson PM, editors. Nitrogen excretion. Fish physiology. Vol. 20. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 109–48. [Google Scholar]

- Janicke M, Carney TJ, Hammerschmidt M. Foxi3 transcription factors and Notch signaling control the formation of skin ionocytes from epidermal precursors of the zebrafish embryo. Dev Biol. 2007;307:258–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens PA. The metabolism of the aestivating African lungfish. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1964;11:105–17. doi: 10.1016/0010-406x(64)90098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonz MG, Nurse CA. Neuroepithelial cells and associated innervation of the zebrafish gill: a confocal immune-fluorescence study. J Comp Neurol. 2003;461:1–17. doi: 10.1002/cne.10680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JAC, Abel DC, DiBona DR. Effects of salinity on chloride cells in the euryhaline cyprinodontid fish Rivulus marmoratus. Cell Tissue Res. 1989;257:367–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kok WK, Lim CB, Lam TJ, Ip YK. The mudskipper Periophthalmodon schlosseri respires more efficiently on land than in water and vice versa for Boleophthalmus boddaerti. J Exp Zool. 1998;280:86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lam K, Tsui T, Nakano K, Randall DJ. Physiological adaptations of fishes to tropical intertidal environments. In: Val AL, Almeida-Val VMF, Randall DJ, editors. The physiology of tropical fishes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 502–81. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc DFM, Wood CM, Fudge DS, Wright PA. A fish out of water: gill and skin remodeling promotes osmo- and ionoregulation in the mangrove killifish Kryptolebias marmoratus. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2010;83:932–49. doi: 10.1086/656307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwiller SL, O’Donnell MJ, Wright PA. Rapid increase in the partial pressure of NH3 on the cutaneous surface of air-exposed mangrove killifish, Rivulus marmoratus. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:1737–45. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes JM, Boijink CL, Florindo LH, Kalinin AL, Milsom WK, Rantin FT. Hypoxic cardiorespiratory reflexes in the facultative airbreathing fish jeju (Hoplerythrinus unitaeniatus): role of branchial O2 chemoreceptors. J Comp Biol. 2010;180:797–811. doi: 10.1007/s00360-010-0461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low WP, Lane DJW, Ip YK. A comparative study of terrestrial adaptations of the gills in three mudskippers—Periophthalmus chrysospilos, Baleophthalmus boddaerti and Periophthalmus schlosseri. Biol Bull. 1988;175:434–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nikinmaa M, Rees RB. Oxygen-dependent gene expression in fishes. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:R1079–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00626.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson GE. Gill remodeling in fish—a new fashion or an ancient secret? J Exp Biol. 2007;210:2403–9. doi: 10.1242/jeb.000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong KJ, Stevens ED, Wright PA. Gill morphology of the mangrove killifish (Kryptolebias marmoratus) is plastic and changes in response to terrestrial air exposure. J Exp Biol. 2007;210:1109–15. doi: 10.1242/jeb.002238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JY. Structure of the skin of an air-breathing mudskipper, Periophthalmus magnuspinnatus. J Fish Biol. 2002;60:1543–50. [Google Scholar]

- Park JY, Lee YS, Kim IS, Kim SY. A comparative study of the regional epidermis of an amphibious mudskipper fish, Baleophthalmus pectinirostris (Gobiidae, Pisces) Folia Zool. 2003;52:431–40. [Google Scholar]

- Perry SF, Jonz MG, Gilmour KM. Oxygen sensing and the hypoxic ventilatory response. In: Richards JG, Farrell AP, Brauner CJ, editors. Hypoxia. Fish physiology. Vol. 27. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2009. pp. 193–253. [Google Scholar]

- Randall D, Burggren W, French K. Eckert animal physiology: mechanisms and adaptations. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Company; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Regan KS, Jonz MG, Wright PA. Neuroepithelial cells and the hypoxia emersion response in the amphibious fish Kryptolebias marmoratus. J Exp Biol. 2011;214:2560–8. doi: 10.1242/jeb.056333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodela TM, Wright PA. Characterization of diurnal urea excretion in the mangrove killifish, Rivulus marmoratus. J Exp Biol. 2006a;209:2696–703. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodela TM, Wright PA. Metabolic and neuroendocrine effects on diurnal urea excretion in the mangrove killifish Rivulus marmoratus. J Exp Biol. 2006b;209:2704–12. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutjes HA, Nieveen MC, Weber RE, Witte F, Van den Thillart GE. Multiple strategies of Lake Victoria cichlids to cope with lifelong hypoxia include hemoglobin switching. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1376–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00536.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltys HA, Jonz MG, Nurse CA. Comparative study of gill neuroepithelial cells and their innervations in teleosts and Xenopus tadpoles. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;323:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer MDJ. Adaptations of amphibious fish for surviving life out of water. Fish Fisheries. 2005;6:186–211. [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtfeger WK, Bereiter-Hahn J. Transient occurrence of chloride cells in the abdominal epidermis of the guppy, Poecilia reticulata Peters, adapted to sea water. Cell Tissue Res. 1978;191:463–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00219809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingles A, McKenzie DJ, Claireaux G, Domenici P. Reflex cardioventilatory responses to hypoxia in the flathead gray mullet (Mugil cephalus) and their behavioral modulation by perceived threat of predation and water turbidity. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2005;78:744–55. doi: 10.1086/432143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smatresk NJ. Ventilatory and cardiac reflex responses to hypoxia and NaCN in Lepisosteus osseus, an air-breathing fish. Physiol Zool. 1986;59:385–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sollid J, De Angelis P, Gundersen K, Nilsson GE. Hypoxia induces adaptive and reversible gross morphological changes in crucian carp gills. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:3667–73. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollid J, Weber RE, Nilsson GE. Temperature alters the respiratory surface area of crucian carp Carassius carassius and goldfish Carassius auratus. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1109–16. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeger HU, Bridges CR. A method for long-term measurement of respiration in intertidal fishes during simulated intertidal conditions. J Fish Biol. 1995;47:308–20. [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T, Ishimatsu A, Oikawa S, Kanda T, Hishida Y, Khoo KH. Mudskipper Periophthalmodon schlosseri can repay oxygen debts in air but not in water. J Exp Zool. 1999;284:265–70. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-010x(19990801)284:3<265::aid-jez3>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatarenkov A, Lima SMQ, Taylor DS, Avise JC. Long-term retention of self-fertilization in a fish clade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14456–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907852106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DS. Biology and ecology of Rivulus marmoratus. Florida Sci. 2000;63:242–55. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DS, Davis WP, Turner BJ. Rivulus marmoratus: ecology of distributional patterns in Florida and the central Indian river lagoon. Bull Mar Sci. 1995;57:202–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui TKN, Randall DJ, Chew SF, Ji Y, Wilson JM, Ip YK. Accumulation of ammonia in the body and NH3 volatilization from alkaline regions of the body surface during ammonia loading and exposure to air in the weather loach Misgurnus anguillicaudatus. J Exp Biol. 2002;205:651–9. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turko AJ, Earley RL, Wright PA. Behaviour drives morphology: voluntary emersion patterns shape gill structure in genetically identical mangrove rivulus. Anim Behav. 2011;82:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Turner BJ, Elder JF Jr, Laughlin TF, Davis WP. Genetic variation in clonal vertebrates detected by simple-sequence DNA fingerprinting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5653–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijenhoek RC. Homozygosity and interstrain variation in the self-fertilizing hermaphroditic fish, Rivulus marmoratus. J Hered. 1985;76:82–4. [Google Scholar]

- Weihrauch D, Wilkie MP, Walsh PJ. Ammonia and urea transporters in gills of fish and aquatic crustaceans. J Exp Biol. 2009;212:1716–30. doi: 10.1242/jeb.024851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells MG. Blood-gas transport and hemoglobin function: adaptations for functional and environmental hypoxia. In: Richards IG, Farrell AP, Brauner CJ, editors. Hypoxia. Fish physiology. Vol. 27. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2009. pp. 255–99. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead A. Comparative genomics in ecological physiology: toward a more nuanced understanding of acclimation and adaptation. J Exp Biol. 2012;215:884–91. doi: 10.1242/jeb.058735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PA. Nitrogen excretion: three end products, many physiological roles. J Exp Biol. 1995;198:273–81. doi: 10.1242/jeb.198.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PA, Wood CM. A new paradigm for ammonia excretion in aquatic animals: role of rhesus (Rh) glycoproteins. J Exp Biol. 2009;212:2303–12. doi: 10.1242/jeb.023085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoya S, Tamura OS. Fine structure of the skin of the amphibious fishes, Boleophthalmus pectinirostris and Periophthalmus cantonensis, with special reference to the location of blood vessels. J Morphol. 1992;214:287–97. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1052140305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Taniguchi T, Takita T, Ali AB. On the epidermal structure of Boleophthalmus and Scartelaos mudskippers with reference to their adaptation to terrestrial life. Ichthyol Res. 2000;47:359–66. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.