Abstract

Objective

Little is known about the effects of disaster exposure and intensity on the development of mental disorders among pregnant women. The aim of this study was to examine the effect of exposure to Hurricane Katrina on mental health in pregnant women.

Design

Prospective cohort epidemiological study.

Setting

Tertiary hospitals in New Orleans and Baton Rouge, USA.

Participants

Women who were pregnant during Hurricane Katrina or became pregnant immediately after the hurricane.

Main outcome measures

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression.

Results

The frequency of PTSD was higher in women with high hurricane exposure (13.8%) than women without high hurricane exposure (1.3%), with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 16.8; 95 % confidence interval (CI): 2.6-106.6; after adjustment for maternal race, age, education, smoking and alcohol use, family income, parity, and other confounders. The frequency of depression was higher in women with high hurricane exposure (32.3%) than women without high hurricane exposure (12.3%), with aOR of 3.3 (1.6-7.1). Moreover, the risk of PTSD and depression increased with an increasing number of severe experiences of the hurricane.

Conclusion

Pregnant women who had severe hurricane experiences were at a significantly increased risk for PTSD and depression. This information should be useful for screening pregnant women who are at higher risk of developing mental disorders after disaster.

Keywords: Depression, disaster, Hurricane Katrina, post-traumatic stress disorder, pregnancy

Background

Hurricane Katrina, which made landfall as a Category 4 storm on August 29, 2005 along the central Gulf Coast, has been described as “the worst catastrophe, or set of catastrophes” in US history, referring to the hurricane itself as well as the flooding of New Orleans. Katrina and its aftermath cost more than 1,600 lives, caused at least $100 billion worth of damage, and displaced over a million people 1-3. Given the massive evacuation of population, enormous physical destruction, environmental degradation, and human misery, there is likely to be significant mental health effects from Hurricane Katrina in the affected areas 2, 3. Previous studies have demonstrated a significant increase in the prevalence of mental disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following floods 4, 5 and other natural disasters in men and women 6. Levels of depression, anxiety, and somaticization are also raised in the aftermath of disaster 7. In addition, intensity of exposure to disaster is one of the strongest predictors of later psychopathology 8.

Women have consistently been demonstrated to have a higher prevalence of PTSD and other mental disorders after disasters than men 6, 7, 9. Pregnant women may be a particularly vulnerable population during disasters, and their experiences may influence not only their own health but also that of their unborn children 1, 10. However, little is known about the effects of disaster exposure and intensity on the development of mental disorders among pregnant women. The objective of this study was to examine the effect of exposure to Hurricane Katrina on the risk of PTSD and depression among pregnant women.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study at two antenatal care clinics at Tulane-Lakeside Hospital in New Orleans and Woman’s Hospital in Baton Rouge (about 120 kilometers away from New Orleans and less exposed to Hurricane Katrina) between January 2006 and June 2007 11. Two hundred-twenty women from New Orleans and 81 women from Baton Rouge who were pregnant during Hurricane Katrina or became pregnant in the six months after Katrina were recruited. Inclusion criteria were speaking English, planning to deliver at the study hospitals, being over 18 years old, (for New Orleans) living in the area before the storm, and (for Baton Rouge) not having an extensive experience of the hurricane (evacuating or having a relative die). Pregnant women were recruited during an antenatal care visit. After recruitment, the women were interviewed regarding their hurricane experience and their psychological response to the hurricane (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD] and depression), as well as for information regarding potential confounding and mediating factors related to mental disorders. These included demographics, socioeconomic status, tobacco and alcohol use, and reproductive and medical history.

The main exposure of this study is high hurricane experience. The hurricane experience questions were adapted from a questionnaire used in the Social and Cultural Dynamics of Disaster Recovery study after Hurricane Andrew 12, 13. High hurricane exposure was defined as having three or more severe experiences of the following events: feeling that one’s life was in danger, experiencing illness or injury to self or a family member, walking through floodwaters, severe home damage, not having electricity for more than one week, having a loved one die, or seeing someone die.

Outcome variables of this study include PTSD and depression. Symptoms of PTSD were assessed with the validated Posttraumatic Stress Checklist (PCL) - Civilian Version. This scale is a commonly used, brief 17-item inventory of PTSD-like symptoms, with response alternatives ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) 14. Using a 5-point scale, respondents indicate how much they are bothered by each PTSD symptom in the past month. In a study, Weathers et al. found an alpha of 0.97 and a test-retest reliability of 0.96. They also found a cut-off of 50 had a sensitivity of 0.82, a specificity of 0.84, and a kappa of 0.64 against a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID)-based PTSD diagnosis 14. This scale performs particularly well when PTSD relative to a specific event is being assessed, as is the case in this study 15. In accord with previous studies, a cutoff value of 50 was used to define PTSD in the present study. Maternal depression was assessed by using the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EDS). The EDS was first developed for the assessment of postpartum depression under the name of the “Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale” 16. It was then validated in childbearing women and in non-postnatal women 17, 18. EDS has 10 items (questions). Each item is scored on a four-point scale (from 0 to 3), with minimum and maximum overall scores ranging 0 to 30. The internal consistency of this scale was found to be good in pregnant women (Cronbach’s α=0.85) 19. A cutoff value of 12 was used to define depression in the present study. Other covariates included maternal age, race, parity, education, marital status, smoking, alcohol consumption, family income, and previous history of pregnancies.

Chi-square tests were used to examine differences in proportions, and multiple logistic regression was used to adjust for the effects of confounding variables. The adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived from the coefficients of the logistic models and their standard errors. All p values were two-tailed, and the significance level selected was 0.05. Data were analyzed using SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc.; Chicago, Ill).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Tulane University and the participating hospitals, and all subjects entering the study signed written informed consent.

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study population. After excluding missing data, 7.2% were teenagers and 19.5% were ≥ 35 years old; 43.8% were non-Hispanic white and 41.6% were non-Hispanic black; 45.5% were primiparous. Of the women, 5.3% had a prior history of low birth weight infants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population

| Characteristics§ | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| New Orleans (Tulane-Lakeside Hospital) | 220 | 73.0 |

| Baton Rouge (Woman's Hospital) | 81 | 27.0 |

| Maternal age (yrs) | ||

| ≤ 19 | 20 | 7.2 |

| 20-34 | 203 | 73.3 |

| ≥ 35 | 54 | 19.5 |

| Parity | ||

| Primiparous | 125 | 45.5 |

| Multiparous | 150 | 54.9 |

| Family income | ||

| < $20,000 | 60 | 25.0 |

| $20,000-$60,000 | 94 | 39.0 |

| >$60,000 | 87 | 36.0 |

| Race | ||

| White | 96 | 43.8 |

| Black | 91 | 41.6 |

| Other | 32 | 14.6 |

| History of low birth weight | ||

| Yes | 13 | 5.3 |

| No | 232 | 94.7 |

| PTSD | ||

| Yes | 13 | 4.4 |

| No | 285 | 94.6 |

| Depression | ||

| Yes | 43 | 14.4 |

| No | 255 | 84.6 |

Excluding missing data

The overall rates of PTSD and depression were 4.4% and 14.4% (Table 1). There was no difference in the rates of PTSD and depression between New Orleans and Baton Rouge. The rate of PTSD was 4.6% in New Orleans and 3.8% in Baton Rouge (p>0.05), and the rate of depression was 15.1% in New Orleans and 12.7% in Baton Rouge (p>0.05). There was no difference in the rate of PTSD and depression between women who were pregnant during Hurricane Katrina (5.9% and 17.2%) and women who became pregnant in the six months after Katrina (3.2% and 14.2%), p>0.05.

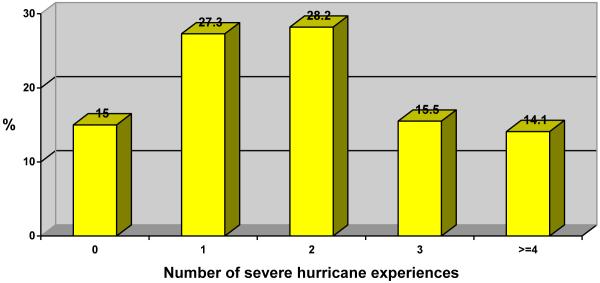

A majority of the study population were exposed to one or more severe hurricane experiences (Figures 1 and 2), including feeling that one’s life was in danger (34.9%), experiencing illness or injury to self (10.5%) or a family member (19.2%), walking through floodwaters (7.0%), severe home damage (50.9%), not having electricity for more than one week (60.3%), having a loved one die (7.9%), or seeing someone die (3.5%). Table 2 presents the effect of hurricane experience on the risk of mental disorders. The frequency of PTSD was higher in women with high hurricane exposure (13.8%) than women without high hurricane exposure (1.3%), with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 16.8; 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.6-106.6; after adjustment of maternal race, age, education, parity, smoking, family income, and prior history of low birth weight. The frequency of depression was higher in women with high hurricane exposure (32.3%) than women without high hurricane exposure (12.3%), with aOR of 3.3 (1. 6-7.1). Figure 2 shows the frequency of women who had none, one, two, three, and four or more of the severe hurricane experiences indicated in Figure 1. There was a trend toward increased rates of PTSD and depression with an increasing number of severe hurricane experiences or events (Table 2). Compared to women who had no severe hurricane experience, after adjustment of the confounders indicated above, the adjusted ORs and 95% CIs of depression for women who had one, two, three, and four or more severe hurricane experiences were 1.9 (0.39-10.2), 1.8 (0.33-9.4), 4.2 (0.77-22.6), and 8.0 (1.5-42.7), respectively. Women who experienced three and four or more severe hurricane events had a markedly increased risk of PTSD [aOR: 8.7; 95% CI: 0.62-122.6 and 31.9 (2.2-471.8)].

Figure 1.

Frequency of the severe experience of the hurricane among pregnant women

Figure 2.

Frequency of women who had severe hurricane experience

Table 2.

Hurricane Katrina Experience and Risk of PTSD and Depression

| Variables§ | PTSD | Depression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| % | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)† | % | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)† | |

| High hurricane exposure (≥ 3 events): | ||||||

| No (n=155) | 1.3 | Referent | Referent | 12.3 | Referent | Referent |

| Yes (n=65) | 13.8 | 12.3 (2.6-58.7) | 16.8 (2.6-106.6) | 32.3 | 3.4 (1.7-6.9) | 3.3 (1.6-7.1) |

| No. of hurricane experiences/events: | ||||||

| 0 (n=33) | 0.0 | 6.1 | Referent | Referent | ||

| 1 (n=60) | 1.7 | Referent | Referent | 13.3 | 2.4 (0.48-12.0) | 1.9 (0.39-10.2) |

| 2 (n=62) | 1.6 | 0.9 (0.06-15.8) | 1.0 (0.05-21.3) | 14.5 | 2.6 (0.53-13.0) | 1.8 (0.33-9.4) |

| 3 (n=34) | 8.8 | 5.7 (0.57-57.2) | 8.7 (0.62-122.6) | 26.5 | 5.6 (1.1-28.2) | 4.2 (0.77-22.6) |

| ≥4 (n=31) | 19.4 | 14.2 (1.6-123.8) | 31.9 (2.2-471.8) | 38.7 | 9.8 (2.0-48.6) | 8.0 (1.5-42.7) |

Excluding missing data

aOR of logistic regression adjusted for maternal age, race, parity, education, martial status, smoking, alcohol consumption, family income.

Discussion

Literature regarding the effect of natural disasters such as hurricanes on mental disorders among pregnant women is scarce. Post-disaster psychological traumas and disorders are relatively common after disasters 20. Disasters are estimated to produce an approximately 17% increase in community psychopathology 21, with PTSD being the most frequent and serious psychological disorder 6. The reported prevalence of PTSD among direct victims of disaster ranges from 30-40%, while the prevalence in the general population is about 5-10% 6. Depression is common among pregnant women regardless of circumstances, with estimated prevalence ranging from 5.3-37.9% (average prevalence 7.4%, 12.8%, and 12.0% for the first, second, and third trimesters, respectively) 22. However, the present study found relatively low rates of PTSD (4.4%) and depression (14.4%) among pregnant women who experienced Hurricane Katrina.

Psychosocial stress/trauma during pregnancy has been difficult to study due to its non-random nature, but Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath, through providing a severely stressful event for everyone in New Orleans, gives a more random distribution. The most and least privileged have had to deal with severe and chronic stressors, including relocation, tremendous uncertainty, discontinuity in medical care, social network disruption, and loss or potential loss of lives, jobs, and property--in some cases of everything that was owned. However, our findings of the lower rates of mental disorders among pregnant women underscore that although the exposure to such a devastating disaster as Hurricane Katrina could be a significant risk factor, pregnant women did not develop PTSD and depression at particularly high levels.

We found no significant difference in prevalence of PTSD and depression between New Orleans and Baton Rouge. However, 38.5% of women in Baton Rouge felt that their life was in danger during the storm, compared to 33.5% of women in New Orleans (p > 0.05); 3.1% of women in Baton Rouge had a loved one die, compared to 9.8% of women in New Orleans (p > 0.05); and 36.9% of women in Baton Rouge lived in house or apartment without electricity for more than one week, compared to 69.5% of women in New Orleans (p <0 .05). Because of its geographic location close to New Orleans, women in Baton Rouge also experienced certain degree of stress/anxiety that could increase the risk levels of PTSD and depression, even though Baton Rouge was not directly hit by the hurricane.

The rates of PSTD and depression found in the present study were low compared to other studies of Hurricane Katrina. In study of a general population of 815 adults, Kessler et al. reported PTSD to be 14.9%, 5-8 months after Katrina 23. Desalvo et al studied Tulane University employees and found the prevalence of PTSD symptoms was 19.2% 24. The reasons for the observed lower rate of PTSD and depression among pregnant women are unclear. Most of the women in our study were in the early stages of pregnancy at Katrina or became pregnant in the six months after Katrina; results might be different in women who gave birth immediately after the storm. However, the period of severe stresses and difficulties due to the hurricane extended far into the fall. It is possible that the most severely affected women may not have returned to New Orleans. On the other hand, other studies in wartime found that mothers often do relatively well in overall adverse conditions 25. During a disaster period, pregnant women may have a better access to care through relief programs and receive support from family and society, or pregnancy itself may be a protective factor against mental disorders. Our data have indicated that many pregnant women are resilient from the mental health consequences of disaster, and perceive benefits after a traumatic experience 26.

Previous studies reported that disaster characteristics (especially the presence of physical injury, fear of death, and property loss) were better predictors of mental disorders than was specific disaster type 8. In the present study, we do find that women who had severe hurricane experiences (i.e., feeling that one’s life was in danger, experiencing illness or injury to self or a family member, walking through floodwaters, severe home damage, not having electricity for more than one week, having a loved one die, or seeing someone die) were at increased risk of developing PTSD and depression. In particular, pregnant women who experienced three or more of these severe events during the hurricane were at markedly increased risk of PTSD and depression, after adjustment for maternal age, race, parity, education, family income and other confounding variables. The present study highlights that, rather than a general exposure to disaster, exposure to specific severe disaster events and the intensity of the disaster experience may be better predictors of PTSD and depression.

Many factors could affect the effects of disaster experience on mental health. Although the nature and extent of exposure to the hurricane and its consequences will largely determine the psychological reaction, this may be modified by the woman’s social networks, coping style, level of deprivation before the hurricane, and perhaps pregnancy itself. Apart from the nature and intensity of the disaster experience, perceived social support, buffers, the timing of disaster exposure during gestation, and other risk factors, such as race and biomedical factors, may mediate the effect of disaster experience on mental distress 27-29, and these factors in association with PTSD or depression warrant further study.

Several limitations must be pointed out. Most of the women in our study were in the early stages of pregnancy at Katrina or became pregnant in the six months after Katrina; results might be different in women who gave birth immediately after the storm. The sample size of the present study is relatively small (or is reduced by missing information). This may limit statistical power to detect statistical significance in the associations. Our data do not have information on pregnant women’s prior history of PTSD, prior history of diagnosed depression, and prior history of previous outpatient or inpatient psychiatric treatment for PTSD or depression. These variables are crucial predictors for having mental disorders in disaster settings. If feasible, future study should collect the information of these variables that are likely confounders or causal inference for the relationship between the disaster experience and the risk of mental disasters in women. Finally, our data are limited to a baseline analysis at a single moment in time, and they do not allow us to establish the long-term effects of hurricane exposure on mental health. Future studies, however, will examine the factors associated with PTSD or depression over time, as well as how timing of exposure during gestation may affect mental health outcomes.

Women who had severe hurricane experiences were at a significantly increased risk of having PTSD and depression. This information should be useful for screening pregnant women who are at higher risk of developing mental disorders after disaster.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH/NICHD 3U01HD040477-0552

References

- 1.Buekens P, Xiong X, Harville E. Hurricanes and pregnancy. Birth. 2006;33:91–3. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2006.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travis J. Hurricane Katrina. Scientists’ fears come true as hurricane floods New Orleans. Science. 2005;309:1656–9. doi: 10.1126/science.309.5741.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson JF. Health and the environment after Hurricane Katrina. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:153–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waelde LC, Koopman C. Symptoms of acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder following exposure to disasterous flooding. J Trauma Dissoc. 2001;2:37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahern M, Kovats RS, Wilkinson P, Few R, Matthies F. Global health impacts of floods: epidemiologic evidence. Epidemiol Rev. 2005;27:36–46. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxi004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiol Rev. 2005;27:78–91. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxi003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bromet E, Dew MA. Review of psychiatric epidemiologic research on disasters. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17:113–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briere J, Elliott D. Prevalence, characteristics, and long-term sequelae of natural disaster exposure in the general population. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:661–79. doi: 10.1023/A:1007814301369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armenian HK, Morikawa M, Melkonian AK, et al. Loss as a determinant of PTSD in a cohort of adult survivors of the 1988 earthquake in Armenia: implications for policy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:58–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102001058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cordero JF. The epidemiology of disasters and adverse reproductive outcomes: lessons learned. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;101(Suppl 2):131–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101s2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiong X, Harville EW, Mattison DR, Elkind-Hirsch K, Pridjian G, Buekens P. Exposure to Hurricane Katrina, post-traumatic stress disorder and birth outcomes. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336:111–5. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318180f21c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norris FH, Perilla JL. Stability and change in stress, resources, and psychological morbidity: who suffers and who recovers: Findings from Hurricane Andrew. Anxiety Stress Coping. 1999;12:363–96. doi: 10.1080/10615809908249317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981-2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–39. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the clinician-adminstered posttraumatic stress disorder scale. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norris FH, Hamblen JL. Standardized self-report measures of civilian trauma and PTSD. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD. The Guildford Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox JL, Chapman G, Murray D, Jones P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in non-postnatal women. J Affect Disord. 1996;39:185–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray D, Cox JL. Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh depression scale. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1990;8:99–107. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dayan J, Creveuil C, Herlicoviez M, et al. Role of anxiety and depression in the onset of spontaneous preterm labor. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:293–301. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voelker R. Katrina’s impact on mental health likely to last years. Jama. 2005;294:1599–600. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.13.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubonis AV, Bickman L. Psychological impairment in the wake of disaster: the disaster-psychopathology relationship. Psychol Bull. 1991;109:384–99. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson TR. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:698–709. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Galea S, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Ursano RJ, Wessely S. Trends in mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:374–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeSalvo KB, Hyre AD, Ompad DC, Menke A, Tynes LL, Muntner P. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in a New Orleans workforce following Hurricane Katrina. J Urban Health. 2007;84:142–52. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9147-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buekens P, Miller CA. Pre-natal care in occupied Belgium during the Second World War. Eur J Public Health. 1996;6:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harville EW, Xiong X, Buekens P, Pridjian G, Elkind-Hirsch K. Resilience after hurricane Katrina among pregnant and postpartum women. Women’s Health Issues. 20:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norris FH, Kaniasty K. Received and perceived social support in times of stress: a test of the social support deterioration deterrence model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71:498–511. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Gao L, Zhang H, Zhao C, Shen Y, Shinfuku N. Post-earthquake quality of life and psychological well-being: longitudinal evaluation in a rural community sample in northern China. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54:427–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2000.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joseph S, Yule W, Williams R, Andrews B. Crisis support in the aftermath of disaster: a longitudinal perspective. Br J Clin Psychol. 1993;32(Pt 2):177–85. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1993.tb01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]