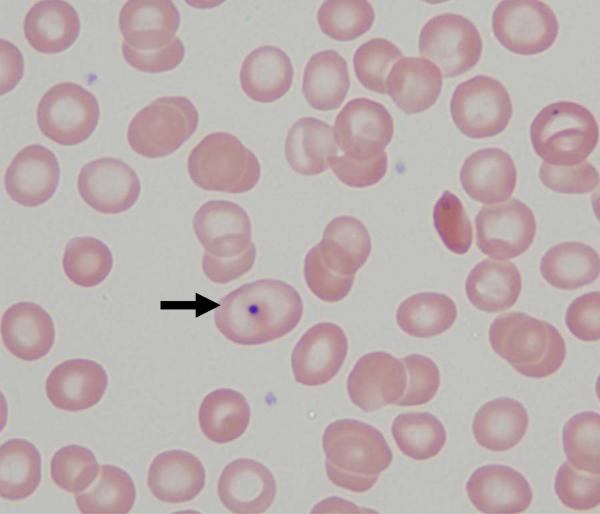

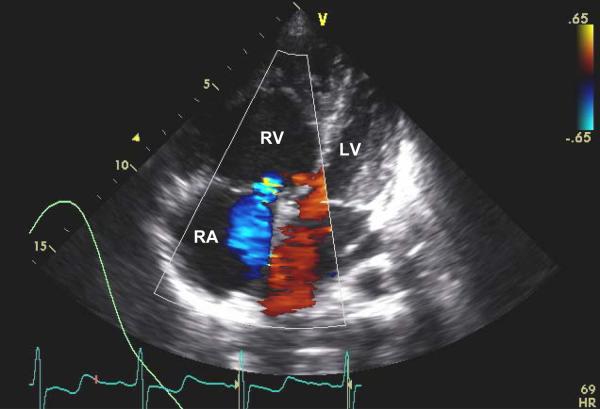

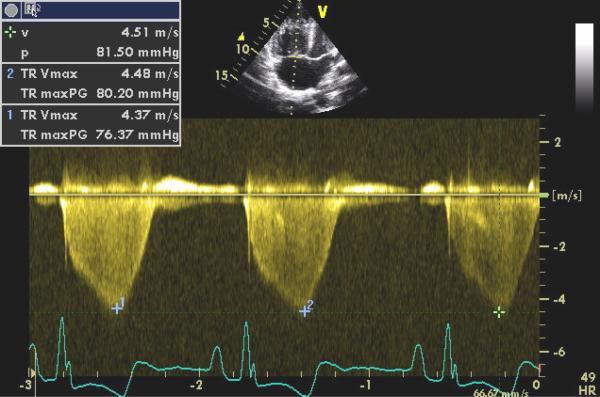

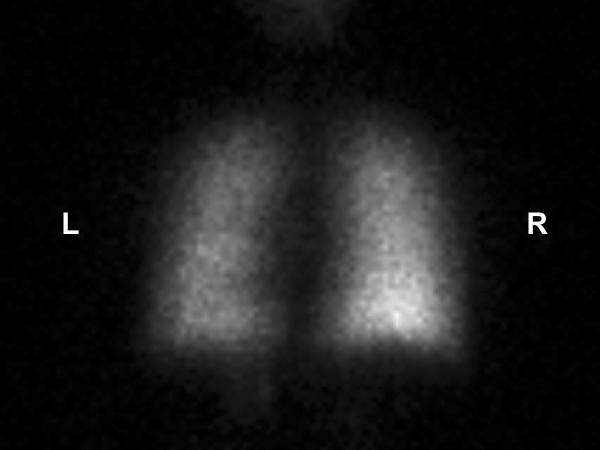

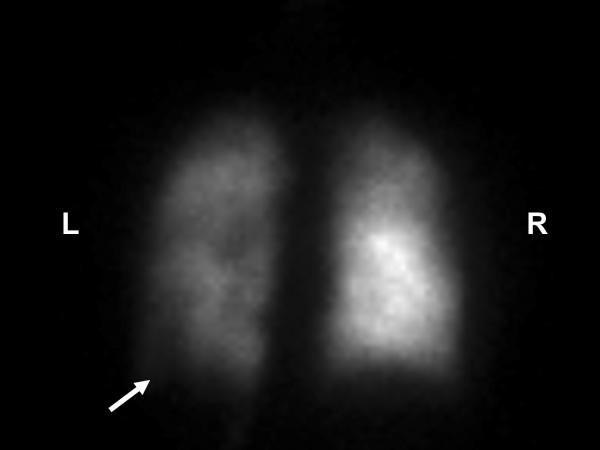

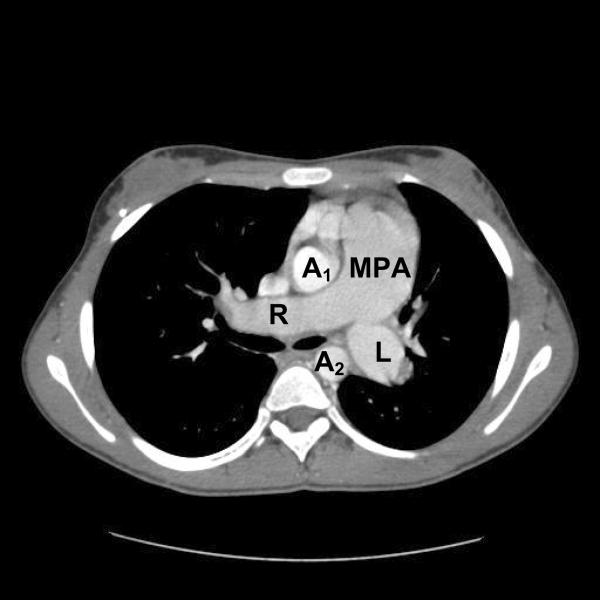

A 15 year old adolescent girl with homozygous sickle cell disease presented with a six month history of progressive shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, and chest pain. Her past history was significant for a prior thrombotic cerebrovascular accident treated with long term transfusion therapy, two prior episodes of pulmonary emboli treated with chronic anticoagulation (2 and 5 years prior to presentation), and a prior diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. The initial baseline pulmonary hypertension evaluation prior to treatment and 2 years prior to presentation included a right heart catheterization with a right atrial pressure (RAP) of 8 mmHg, mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) of 43 mmHg (normal <25), cardiac index (CI) of 3.08 L/min./m2 (normal >2.50), pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) 902 dynes/sec./cm5, and a mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) of 65%. In addition, a pulmonary angiogram seven months prior to referral showed normal perfusion of the central pulmonary arteries, but filling defects were noted in the third and fourth order PA branches of the left lower lobe, the lateral aspect of the right middle lobe, and the lateral aspect of the right upper lobe. A surgical evaluation at that time concluded that these peripheral lesions were inoperable. Despite treatment with supplemental oxygen, hydroxyurea, intensified transfusion therapy, sildenafil, and bosentan, her clinical symptoms progressed over the six months prior to referral. The CBC showed a hemoglobin of 10.5 grams/dL with the majority of erythrocytes representing transfused red cells from her chronic transfusion therapy. Her peripheral blood smear (Image 1) demonstrated anisocytosis, occasional Howell-Jolly bodies (arrow in Image 1), and occasional sickle cells, consistent with her sickle cell anemia and history of transfusion. Further evaluation included a transthoracic Doppler echocardiogram, six minute walk test, a pulmonary ventilation perfusion (VQ) scan, CT angiogram, and right heart catheterization. Color flow Doppler from the echocardiogram (Image 2) showed severe dilation of the right atrium and right ventricle with flattening and bowing of the intraventricular septum into the left ventricle. Normally, the right atrium and right ventricle should be smaller than the corresponding structures on the left during systole. Severe tricuspid regurgitation is also seen (blue flow in Image 2), and the peak Doppler tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRV) was 4.5 meters per second (Image 3). A six minute walk test distance was 120 meters (normal > 500 meters). The VQ scan was intermediate to high probability for a pulmonary embolism with normal ventilation (image 4), a major perfusion defect in the lateral basal segment of the left lower lobe (arrow in image 5), and partial perfusion segmental defects in the left upper lobe, the lingula, and the right upper lobe (image 5) consistent with the findings of the prior pulmonary angiogram. A CT angiogram was performed to further evaluate chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension as a cause of severe pulmonary hypertension. The study was negative for a persistent large vessel thrombus, but did demonstrate severe dilation of the main and the right and left branch pulmonary arteries (Image 6). Normally, the main pulmonary artery has an equal or smaller diameter than the ascending or descending aorta. A right heart catheterization demonstrated a RAP of 8 mmHg, mean PAP of 50 mmHg, cardiac index of 4.04 L/min./m2, PVR 498 dynes/sec./cm5, and SvO2 68% at baseline with no mean PAP decrease in response to either inhaled nitric oxide or sildenafil in the catheterization laboratory. The diagnostic impression was severe progressive pulmonary hypertension secondary to sickle cell disease and inoperable, presumed chronic small vessel pulmonary emboli. She initiated continuous intravenous Epoprostenol therapy, and was discharged to home once she was tolerating an appropriate dose.

Image 1.

Peripheral blood smear taken at the time of referral evaluation showing that the majority of the majority of erythrocytes represent transfused red blood cells (original magnification 100×). The smear demonstrates anisocytosis, occasional Howell-Jolly bodies (indicated by the arrow), and occasional sickle cells.

Image 2.

Two dimensional color flow Doppler image showing a subcostal four chamber view during systole from the transthoracic echocardiogram. The color flow Doppler shows severe tricuspid regurgitation (with the transducer present at the top of the image, the blue area in the right atrium indicates blood flow from the right ventricle back into the right atrium). The image also shows severe dilation of the right atrium and right ventricle with flattening and bowing of the intraventricular septum into the left ventricle. Normally, the right atrium and right ventricle should be smaller than the corresponding structures on the left during systole. RA = right atrium; RV = right ventricle; LV = left atrium; and V = position of the echocardiographer's transducer.

Image 3.

Pulsed Doppler recording of regurgitant blood flow across the tricuspid valve during systole from the patient's transthoracic echocardiogram. The peak Doppler tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRV) shown is 4.5 meters per second.

Image 4.

PA view of the nuclear medicine ventilation scan showing uniform distribution of the technetium 99m DTPA isotope throughout the patient's lungs. L = left and R = right.

Image 5.

PA view of the nuclear medicine perfusion scan of the lungs after intravenous injection with the technetium 99m MAA isotope. The perfusion scan activity is significantly less on the left compared to the right. This image also shows a major perfusion defect in the lateral basal segment of the left lower lobe as indicated by the arrow. Also observed are smaller partial perfusion segment defects in the left upper lobe, the lingula, and the right upper lobe. The pulmonary ventilation perfusion scan was reported to have an intermediate to high probability for the presence of pulmonary emboli. L = left and R = right.

Image 6.

A single axial image from the CT angiogram showing severe dilation of the main pulmonary artery and the right and left branch pulmonary arteries. Normally, the main pulmonary artery has an equal or smaller diameter than the ascending or descending aorta. MPA = main pulmonary artery; LPA = left pulmonary artery; RPA = right pulmonary artery; A1 = ascending aorta; and A2 = descending aorta.