Abstract

The Hedgehog signaling pathway plays an essential role in embryo development and adult tissue homeostasis, in regulating stem cells and is abnormally activated in many cancers. Given the importance of this signaling pathway, we developed a novel and versatile high-throughput, cell-based screening platform using confocal imaging based on the role of β-Arrestin in Hedgehog signal transduction that can identify agonists or antagonist of the pathway by a simple change to the screening protocol. Here we report the use of this assay in the antagonist mode to identify novel antagonists of Smoothened, including a compound (A8) with low nanomolar activity against wild-type Smo also capable of binding the Smo point mutant D473H associated with clinical resistance in medulloblastoma. Our data validate this novel screening approach in the further development of A8 and related congeners to treat hedgehog related diseases, including the treatment of basal cell carcinoma and medulloblastoma.

Keywords: Hedgehog signaling, Smoothened, High-throughput screening, Smo antagonist, Smo mutation

1. Introduction

The evolutionarily conserved Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway is essential for embryonic development, tissue homeostasis, and maintenance of self-renewal potential in adult stem cells1–3. An increasing body of evidence has shown that key components of the pathway: Hh protein, its receptor Patched (Ptc) and an effector receptor Smoothened (Smo), also play pivotal roles in the development of numerous cancers4,5. For example, dysregulation of Hh signaling, resulting from mutations in components of the pathway has been directly implicated in the development of basal cell carcinoma and medulloblastoma6–10. High levels of pathway activity are observed in cancers of the pancreas11,12, proximal gastrointestinal tract11, and prostate13. In mice, about 14–30% of Ptc heterozygous knockout mice develop medulloblastoma14 and the homozygous deletion of Ptc in GFAP-positive progenitor cells resulted in the development of medulloblastoma in 100% of genetically engineered mice15.

Several small molecule inhibitors of the pathway that bind the Smo receptor, such as cyclopamine, IPI-926, and GDC-0449, have been identified with a number of inhibitors under investigation in clinical trials16–21,49. Among these inhibitors, GDC-0449 (Vismodegib) was recently approved by the FDA to treat patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma22–24. Unfortunately, acquired resistance to GDC-0449 was recently described in which an Asp to His point mutation (D473H) was found in the Smo gene. The Smo-D473H mutant receptor is refractory to inhibition by GDC-0449 due to loss of interaction between the drug and receptor17,25. Thus, new Smo inhibitors with pharmacological properties capable of inhibiting wild-type and clinically relevant mutant receptors are needed to overcome acquired drug resistance and extend the duration of response.

A mechanistic understanding of the Hh signaling pathway has evolved over the past decade26. The Hedgehog family of growth factor proteins is comprised of 3 members: Sonic, Desert, and Indian Hedgehog, each known to bind the transmembrane receptor Ptc. In the resting, non-ligand bound state, the unoccupied transmembrane receptor Ptc inhibits the activity of the transmembrane protein Smo. Upon binding of Hh ligand to its receptor Ptc, Smo becomes activated and transduces signaling by activating Gli transcription factors that results in the modulation of Hh responsive genes such as Myc and Ptc.

Activated Smo shares important similarities with canonical G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), including an ability to undergo GPCR kinase-mediated phosphorylation and to recruit β-arrestin2 (βarr2) proteins for endocytosis and signaling. In our previous work27, we found that βarr2 binds Smo at the plasma membrane in an activation-dependent manner, and that the Smo antagonist cyclopamine inhibits the activity of Smo by preventing its phosphorylation and interaction with βarr2. These findings enabled the development of a versatile cell-based high-throughput imaging-based screening platform capable of identifying either agonists or antagonists of the pathway by the presence or absence of cyclopamine, respectively, in the assay. These assay formats led to the discovery of Smo agonist activity in a select subset of commonly used glucocorticoid medications28 and Smo antagonist activity in piperonyl butoxide29, a pesticide synergist present in over 1500 products30 recently associated with delayed learning in children31 and one of the top 10 chemicals detected in indoor dust32. Here, we report the use of this platform to search systematically for Smo inhibitors in small molecule chemical libraries. This effort resulted in the discovery of a number of active hits, including a low nanomolar Smo antagonist (compound A8) that binds to Smo receptors, inhibits the transcriptional activity of Gli, inhibits cell proliferation of neural precursor cells and prevents Hh-signaling dependent hair growth in mice. In contrast to GDC-0449, compound A8 binds the Smo mutant D473H recently associated with medulloblastoma disease progression and resistance to GDC-044917,25,33, thereby providing the basis of a strategy to treat resistant disease.

2. Materials and Methods

Reagents

A library of 5740 compounds (Tripos Gold) were used for high-throughput screening. β-arrestin2 green fluorescent protein (βarr2-GFP), wild-type Smo, Smo-663 mutant, and Gli-luciferase reporter have been previously described27,28. The Smo-D473H mutant construct was generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Purified Sonic Hedgehog was obtained from StemRD. Cyclopamine was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals. [3H]-cyclopamine (specific activity = 20 Ci/mmol) was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals. GDC-0449 (Vismodegib), LDE-225 (NVP-LDE225, Erismodegib) and select hits identified from screening were synthesized by the Small Molecule Synthesis Facility at Duke University.

Primary high-throughput screening assay

U2OS cells stably expressing a chimera Smo-633 receptor and βarr2-GFP were used in HTS screening. Smo-633 was used in this assay because it produces a stronger signal than WT Smo in the βarr2-GFP translocation assay, but is otherwise pharmacologically similar27,34. The antagonist mode screening protocol used here to identify antagonists of Smo is similar to the protocol to identify Smo agonists described previously with the exception that cyclopamine pretreatment was not used prior to the addition of test compounds28.

Smo receptor binding

For competitive binding assays, U2OS cells overexpressing wild-type Smo or Smo-D473H mutant receptors were grown in 24-well plates and fixed with 4%(v/v) formaldehyde/PBS for 20 min at room temperature (RT). Cells were subsequently incubated for 2 h at RT in binding buffer (Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+) containing 25 nM of [3H]-cyclopamine and a range of different concentrations of cyclopamine, GDC-0449, LDE-225 or A8 (from 0 – 10 µM). Cells were then washed with binding buffer and the bound [3H]-cyclopamine was extracted in 200 µl of 0.1N NaOH and neutralized with 200 µl of 0.1N HCl. The amount of [3H]-cyclopamine in the extracts was measured using a scintillation counter.

Gli-luciferase reporter assay

The Gli-luciferase assay was conducted in Shh-LIGHT2 cells, a clonal NIH3T3 cell line stably incorporating Gli-dependent firefly luciferase and constitutive Renilla luciferase reporters35. Cells were treated with purified Sonic Hedgehog protein from StemRD (50ng/mL) together with the corresponding compounds for 2 days. The reporter activity was determined by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

Cell proliferation

Primary neuronal granular cell precursor (GCP) cells were obtained from the cerebellum of 7-day postnatal C57BL/6 mice and labeled with [3H]-thymidine. Proliferation assays were performed as previously described28.

Animal studies

Eight-week-old C57BL/6 female mice were shaved on the dorsal surface and depilated with Nair® (Carter-Wallace, New York, New York). Briefly, the bottom half of the shaved area was treated with Nair for 2 min, and the depilated area rinsed with water to remove residual Nair. Compound A8 was dissolved in a vehicle of 95% acetone/5% DMSO at a concentration of 0.5 mM, and 30 µl of A8 solution or the vehicle were applied topically to the depilated area of mice daily for two weeks. Mice were anesthetized briefly using 3% isoflurane anesthetic inhalant during all procedures. Five mice were included in each treatment group. All animals were treated in accordance with protocols approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Duke University.

NMR Spectroscopy

Full NMR structural identification of Tripos 3910 and compound A8 was achieved from 2D NMR data sets (COSY, TOCSY, HMQC and HMBC) obtained on Agilent 500 and 800 NMR instruments in the Duke NMR Spectroscopy Center.

3. Results

3.1 Identification of compound A8 from screening

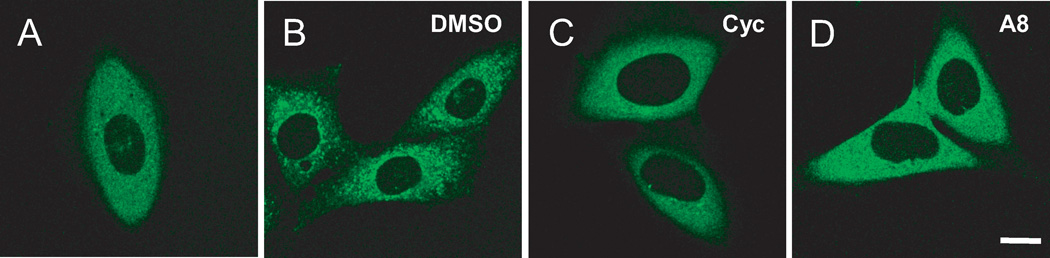

To identify novel Smo inhibitors, we screened chemical libraries using our confocal imaging, cell-based platform assay as the primary high-throughput screening assay. This assay derived from our discovery that co-expression of Smo and βarr2-GFP in cells results in an activation dependent translocation of βarr2-GFP into endocytic vesicles. βarr2-GFP distributes homogenously throughout the cytoplasm when expressed alone in cells (Fig. 1A)28. In marked contrast, cells co-expressing Smo-633 and βarr2-GFP localize βarr2-GFP into intracellular vesicles as aggregates (Fig. 1B). Addition of a Smo antagonist, such as cyclopamine, inhibits the aggregation of βarr2-GFP, as demonstrated by the disappearance of intra-vesicular aggregates (Fig. 1C). Thus, small molecule inhibitors of Smo are identified by visually inspecting the cells for the loss of the punctate pattern. Upon screening of a library of 5740 compounds from Tripos, Inc. at a concentration of 5 µM, we identified 32 hit compounds that inhibited the formation of intracellular βarr2-GFP aggregates similar to that observed with cyclopamine treatment36, one of which was a screening sample Tripos 3910 discussed later (see supplemental Figure 1). Hit compounds in this assay were confirmed by further evaluation in Gli-reporter and [3H]-cyclopamine competition assays, and by testing new solid samples of the hit compounds. At 1 µM concentration, the positive control cyclopamine and hit compounds showed strong inhibition of the Gli-reporter activity36.

Figure 1.

Identification of novel Smo inhibitors in U2OS cells. Inhibitors are detected by the homogenous distribution of the green punctate pattern that results when the intracellular association of βarr2-GFP with Smo is inhibited. Confocal images of U2OS cells stably expressing (A) βarr2-GFP alone, or (B-D) βarr2-GFP co-expressed with Smo-633. Cells were treated for 6 hours with DMSO (B); 5 µM cyclopamine (Cyc) (C); or 5 µM compound A8 (D). Scale bar: 10 µm.

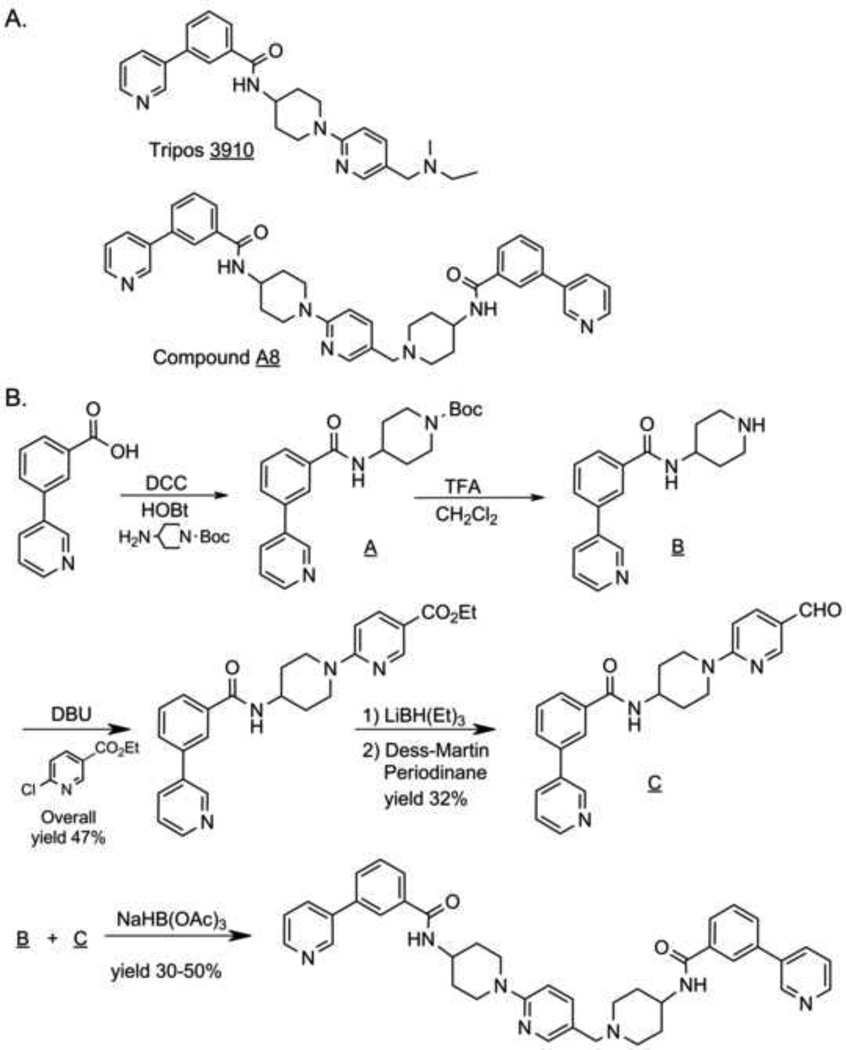

Of the hits obtained from screening, one hit compound (Tripos 3910) (Fig. 2A) synthesized at Duke based on the structure assigned to the material by Tripos, had substantially reduced Smo antagonist activity compared to the previous test samples. Reduced activity associated with this structure was confirmed upon subsequent purification of the Tripos sample in which the major component in the library sample agreed for structure and was less active. Instead, the active substance was found to be a small impurity isolated from the library sample (ca 1.5– 2.6 area percent by UV at λ=210, 254, 280 nm). Storage of the active impurity at room temperature in a DMSO or methanolic solution for 1 week retained activity. Subsequent characterization of this impurity by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and by extensive NMR analysis allowed assignment of structure to the impurity as shown for Compound A8 (Fig. 2A) (see Supplemental Information). Confirmation of the structural assignment was achieved by synthesis of authentic material using the route described in Fig. 2B (see Supplemental Information). Synthesized material matched the isolated material from the library sample by extensive NMR analysis, HRMS, TLC and HPLC. The activity of the synthesized material was confirmed upon testing the synthesized material in the primary Smo/βarr2-GFP assay (Fig. 1D).

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of screening hits and synthesis of A8. (A) Structures of Tripos 3910 and Compound A8. (B) Synthesis of Compound A8

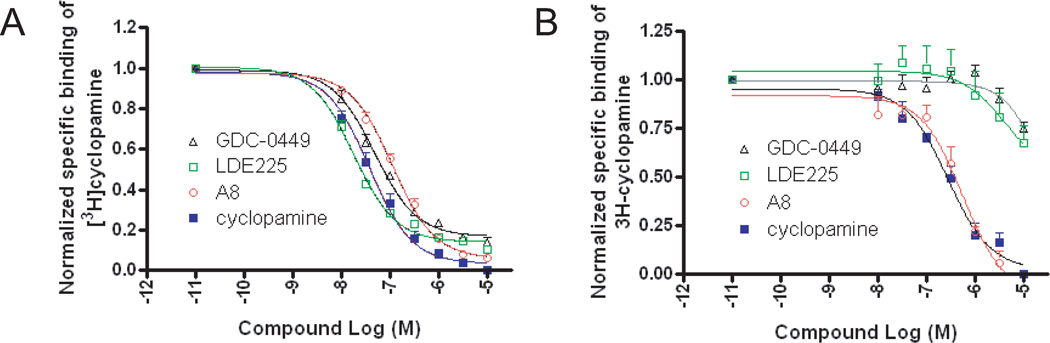

3.2 Compound A8 is a competitive antagonist of Smo

To further characterize the binding of compound A8 to Smo, we tested the ability of A8 to competitively displace [3H]-cyclopamine from Smo in U2OS cells overexpressing wild-type Smo. We previously determined the affinity (Kd) of 3[H]-cyclopamine for wild-type Smo as 12.4 ± 4.2 nM29. In the current study, we performed competition binding assays and found cyclopamine, GDC-0449, LDE-22537 and A8 completely displaced 25 nM of [3H]-cyclopamine from Smo with similar affinities, Ki = 12.7±1.7 nM, 16.2±2.1 nM, 6.0±1.4 nM and 37.9±3.7 nM, respectively (Fig. 3A). Given the importance of mutations in resistance to anticancer therapies, we tested whether A8 is capable of binding to a mutant Smo receptor (Smo-D473H) recently associated with clinical resistance and disease progression to GDC-0449 therapy17,25,33. Using U2OS cells overexpressing Smo-D473H receptors, we conducted saturation binding experiments with 3[H]-cyclopamine against the mutant SmoD473H receptor and determined its Kd as 116 ± 21nM (see Supplemental Figure 2). Consistent with previous reports, competition binding studies with GDC-0449 confirmed it was largely ineffective at competing for binding the mutant receptor and only partially displaced [3H]-cyclopamine at high concentration (10 µM) (Fig. 3B). Another leading Smo antagonist in clinical trials, LDE-225 (Erismodegib), was also largely ineffective. However, both A8 and cyclopamine were able to completely displace [3H]-cyclopamine from Smo-D473H receptors (Kis of 478±123 nM and 232±53 nM, respectively Fig. 3B). Taken together, these results suggest that A8 competes with cyclopamine for the same binding site on Smo and binds both wild-type Smo and the Smo-D473H mutant receptor.

Figure 3.

Compound A8 competitively displaces [3H]-cyclopamine binding to wild-type Smo and mutant Smo-D473H. Competitive binding of [3H]-cyclopamine with Smo antagonists was performed in fixed U2OS cells overexpressing wild-type Smo (A) and Smo-D473H (B). Results were normalized to the maximal binding of [3H]-cyclopamine over baseline and were analyzed by fitting to a one-site competition curve using Graphpad Prism. Data were acquired in duplicate from three independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± SEM.

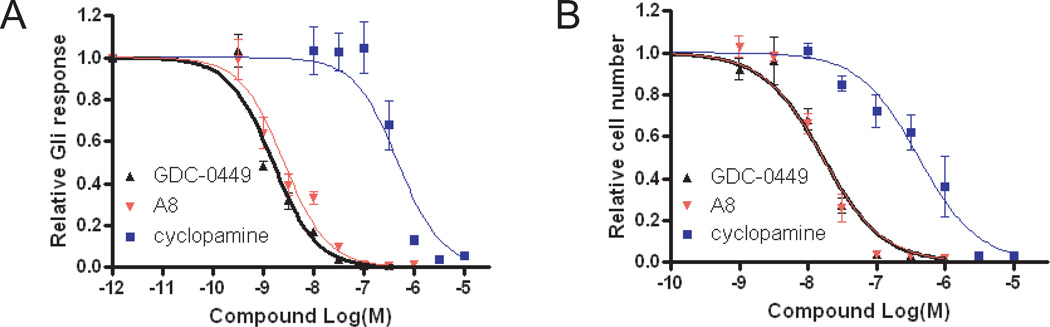

3.3 Compound A8 inhibits Gli activity and proliferation of mouse cerebellar Granular Cell Precursor (GCP) cells

We next examined the inhibitory effect of compound A8 on Hh signaling. Since activation of Smo is known to increase the transcriptional activity of Gli, a Gli-luciferase reporter assay was used to measure inhibition of Smo activation38. As expected of an inhibitor of hedgehog signaling targeting Smo, compound A8 effectively inhibited Shh-induced Gli reporter activity (IC50 = 2.6 ± 0.4 nM) in Shh-LIGHT2 cells (Fig. 4A). Inhibition by A8 was comparable to that of GDC-0449 (IC50 = 1.5±0.2 nM) and considerably more potent than Cyclopamine (IC50 = 484±122 nM). Proliferation of cerebellar GCP cells requires Hh signaling39. Thus, a mouse GCP proliferation assay was performed to assess the hedgehog growth-inhibiting effects of compound A8. We found that compound A8 and GDC-0449 were potent inhibitors of GCP proliferation with IC50s of 16.6±2.3 nM and 16.4±2.5 nM, respectively (Fig. 4B). Consistent with the finding that higher concentration of cyclopamine was needed to inhibit Gli activity compared to A8 and GDC-0449 (Fig. 4A), cyclopamine was also a less potent inhibitor of GCP proliferation (IC50 = 414±73nM). Collectively, these results indicate that A8 is a potent inhibitor of Smo activity and is capable of inhibiting Hh-dependent Gli transcription and cell proliferation in vitro.

Figure 4.

Compound A8 inhibits Gli-reporter activity and GCP proliferation. (A) Gli-luciferase response in Shh-LIGHT2 cells treated for 30 hours with Shh in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of cyclopamine (Cyc), GDC-0449, or A8. (B) GCP cells were treated for 48 hours with Shh in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of Cyc, GDC- 0449, or A8. Cells were then exposed to [3H]-thymidine for 16 h and [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured. Data were fit using Graphpad Prism (mean ± SEM, n = 3).

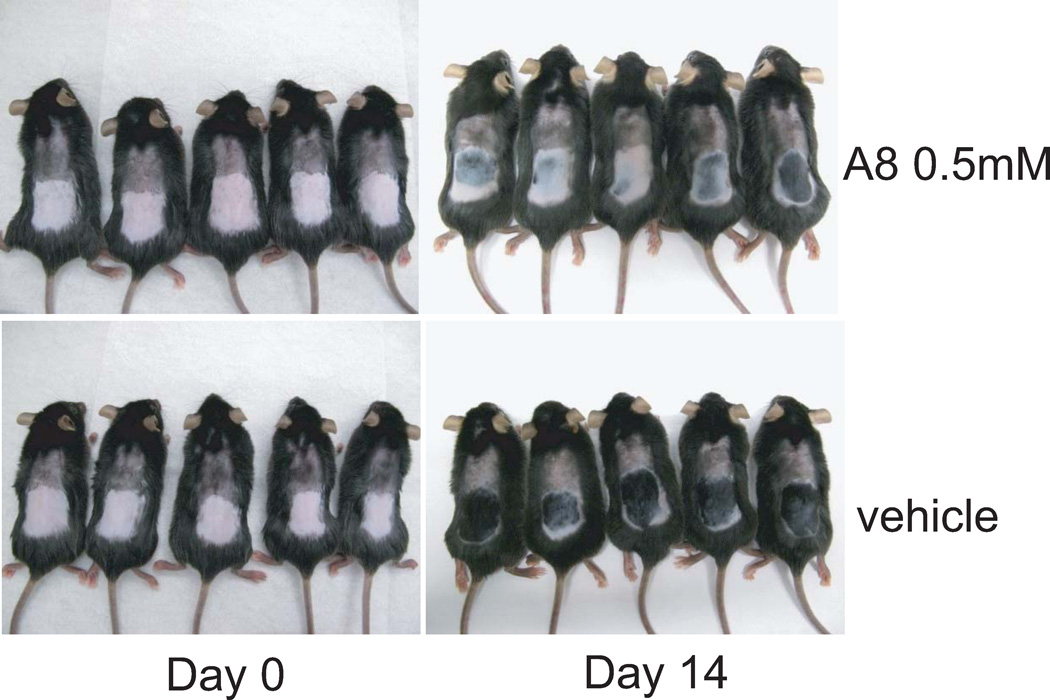

3.4 Compound A8 inhibits hair regrowth in mouse

Hedgehog signaling plays a key role in regulating hair follicle growth40. To determine the efficacy of the novel Smo inhibitor A8 in suppressing Hh signaling in vivo, we used a model of hedgehog inhibition that examines inhibition of hair-growth41–43. Eight-week old female C57BL mice in telogen phase of the hair cycle were used in these experiments44. Chemical depilation with Nair® induces anagen phase and regrowth of hair by activating the Hh signaling pathway. In our experiments, most of the hair on the back of vehicle treated mice grew back 2 weeks after removal with Nair (Fig. 5). In contrast, Hh-induced hair growth was largely inhibited in the A8 treated group, suggesting that A8 also functions as an inhibitor of Hh signaling in vivo (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Compound A8 inhibits Hh-dependent hair growth post depilation. Eight-week old female C57BL mice in the telogen phase of the hair cycle were used. Chemical depilation with Nair activates Hh signaling pathway and induces anagen phase and hair regrowth. This Hh-dependent hair growth is inhibited by daily topical treatment of 30 µl of 0.5 mM Smo antagonist A8 for 2 weeks. The vehicle control is 95% acetone/5% DMSO.

4 Discussion

Following the discovery of oncogenic Ptc mutations, increasing numbers of studies have demonstrated hyperactivation of Hh signaling plays a critical role in promoting the development and progression of various cancers21. As a result, a number of small molecule inhibitors of Hh signaling targeting Smo have progressed into clinical trials, one of which (GDC-0449) was recently approved. Unfortunately, drug resistance has already been described in which mutation of the target decreases affinity of the drug to the target, a common resistance mechanism seen with other recent anticancer drugs. Thus there is a need for potent inhibitors of wild-type Smo with activity against a spectrum of mutations in Smo. This need has prompted recent reports of second generation inhibitors that offer a degree of activity against relevant Smo mutations45–48.

In the work described herein, we utilized a robust and versatile cell-based assay platform based on Smo receptor biochemistry developed in our lab to identify a potent antagonist of Smoothened that is capable of binding a mutated form of the receptor. The Smo/βArr2-GFP high throughput assay platform exploits the discovery that activated wild-type Smo or Smo-633 binds βarr2-GFP and changes its cellular distribution27,28. Addition of a Smo antagonist, such as cyclopamine inhibits the aggregation of Smo-633 with βarr2-GFP. Upon screening small molecule chemical libraries at a concentration of 5 µM, hits were identified by the disappearance of βarr2-GFP intra-vesicular aggregates in cells, similar to the disappearance of aggregates observed with cyclopamine. To control for receptor specificity and to rule-out non-specific mechanisms, hits were cross-screened in the same assay format using the vasopressin2 receptor (V2R), a different seven-transmembrane receptor. In this control assay, cells transfected with V2R and βarr2-GFP are stimulated with the agonist arginine vasopressin. Stimulation causes βarr2-GFP to aggregate and produces a punctate pattern in cells. Aggregation of V2R and βarr2-GFP is not inhibited by the Smo antagonist cyclopamine29 or by A8 (Supplementary Figure 3). This control assay helps ensure the mechanism of inhibition is Smo receptor specific and allows molecules with non-specific mechanisms of inhibition to be ruled-out. Only compounds that inhibited aggregation of Smo and did not inhibit aggregation of V2R were evaluated in confirmatory assays. Using this process, we identified a lead compound (A8) with nanomolar inhibitory activity against wild-type Smo. This compound also bound to a mutated from of Smo associated with clinical resistance (SmoD473H), albeit with a right shift of approximately 13-fold in affinity. The binding affinity of LDE-225 and GDC-0449 to the mutant receptor was too weak (up to 10 uM) to enable determination of a Ki value. The right shift in affinity of A8 was similar to a right shift in affinity of 19 - fold observed for cyclopamine.

The Smo/βArr2-GFP assay is a versatile assay platform that provides the ability to screen for antagonists or agonists by a small change in the screening protocol. Screening in the antagonist mode is as described above. Screening in the agonist mode is accomplished by the addition of 0.1 µM of cyclopamine to the cells prior to screening test libraries28. In the agonist mode, active compounds are identified by the appearance of a green punctate pattern in the cells. The ability to screen cells in an agonist or antagonist mode provides significant advantages to chemical genetic screening approaches while also providing a cellular context to identify molecules with unique mechanisms of action. The follow-up assays used here clearly demonstrate the ability of this innovative assay format to identify authentic inhibitors of Smo that inhibit hedgehog signaling. Structure-activity relationships studies and assays that delineate the anti-cancer effects of the compound A8 and congeners are underway.

5 Conclusions

In summary, a novel high-throughput, cell-based assay platform based on a fundamental finding that activated Smo causes the translocation of βArr2 was capable of identifying Smo antagonists in chemical screening libraries. Here, the assay identified an impurity in a chemical library that is a potent inhibitor of hedgehog signaling and is capable of binding wild-type Smo and a mutated form of Smo associated with clinically resistance in medulloblastoma. The cell-based nature of this assay provides the basis of discovering second generation Hedgehog signaling inhibitors with different binding modes and mechanisms of action that can address drug resistance issues in cancers with activated Hedgehog signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by 5RO1 CA113656-03, the Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation and a Clinical Oncology Research Center Development Grant 5K12-CA100639-08 (RAM). Wei Chen is a V foundation Scholar and an American Cancer Society Research Scholar. NMR instrumentation in the Duke NMR Spectroscopy Center was funded by the NIH, NSF, NC Biotechnology Center and Duke University. The authors gratefully acknowledge this support and the support of Professor Eric Toone and the Duke Small Molecule Synthesis Facility.

Abbreviations

- Smo

Smoothened

- Hh

Hedgehog

- Ptc

Patched

- Shh

Sonic Hedgehog

- β-Arr2

β-Arrestin2

- β-Arr2-GFP

β-Arrestin2-Green Fluorescent Protein chimera

- Gli

Glioma-associated oncogene

- GPCR

G-Protein-Coupled Receptor

- V2R

Vasopressin2 receptor

- HTS

High-Throughput Screening

- WT

wild-type

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- GCP

Granular Cell Precursor

- HBBS

Hanks Balanced Salt Solution

- DCC

N,N'-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide

- TFA

Trifluoroacetic acid

- HOBt

N-Hydroxybenzotriazole

- DBU

1,8-Diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared

References and notes

- 1.Ingham PW, McMahon AP. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3059. doi: 10.1101/gad.938601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dahmane N, Ruiz i Altaba A. Development. 1999;126:3089. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stecca B, Ruiz i Altaba A. J. Neurobiol. 2005;64:476. doi: 10.1002/neu.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Han YG, Spassky N, Romaguera-Ros M, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Aguilar A, Schneider-Maunoury S, Alvarez-Buylla A. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:277. doi: 10.1038/nn2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machold R, Hayashi S, Rutlin M, Muzumdar MD, Nery S, Corbin JG, Gritli- Linde A, Dellovade T, Porter JA, Rubin LL, Dudek H, McMahon AP, Fishell G. Neuron. 2003;39:937. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00561-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Palma V, Lim DA, Dahmane N, Sanchez P, Brionne TC, Herzberg CD, Gitton Y, Carleton A, Alvarez-Buylla A, Ruiz i Altaba A. Development. 2005;132:335. doi: 10.1242/dev.01567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Trowbridge JJ, Scott MP, Bhatia M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604568103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beachy PA, Karhadkar SS, Berman DM. Nature. 2004;432:324. doi: 10.1038/nature03100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taipale J, Beachy PA. Nature. 2001;411:349. doi: 10.1038/35077219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie J, Murone M, Luoh SM, Ryan A, Gu Q, Zhang C, Bonifas JM, Lam CW, Hynes M, Goddard A, Rosenthal A, Epstein EH, Jr, de Sauvage FJ. Nature. 1998;391:90. doi: 10.1038/34201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pietsch T, Waha A, Koch A, Kraus J, Albrecht S, Tonn J, Sorensen N, Berthold F, Henk B, Schmandt N, Wolf HK, von Deimling A, Wainwright B, Chenevix- Trench G, Wiestler OD, Wicking C. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raffel C, Jenkins RB, Frederick L, Hebrink D, Alderete B, Fults DW, James CD. Cancer Res. 1997;57:842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reifenberger J, Wolter M, Weber RG, Megahed M, Ruzicka T, Lichter P, Reifenberger G. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor MD, Liu L, Raffel C, Hui CC, Mainprize TG, Zhang X, Agatep R, Chiappa S, Gao L, Lowrance A, Hao A, Goldstein AM, Stavrou T, Scherer SW, Dura WT, Wainwright B, Squire JA, Rutka JT, Hogg D. Nat. Genet. 2002;31:306. doi: 10.1038/ng916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berman DM, Karhadkar SS, Maitra A, Montes De Oca R, Gerstenblith MR, Briggs K, Parker AR, Shimada Y, Eshleman JR, Watkins DN, Beachy PA. Nature. 2003;425:846. doi: 10.1038/nature01972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thayer SP, di Magliano MP, Heiser PW, Nielsen CM, Roberts DJ, Lauwers GY, Qi YP, Gysin S, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Yajnik V, Antoniu B, McMahon M, Warshaw AL, Hebrok M. Nature. 2003;425:851. doi: 10.1038/nature02009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karhadkar SS, Bova GS, Abdallah N, Dhara S, Gardner D, Maitra A, Isaacs JT, Berman DM, Beachy PA. Nature. 2004;431:707. doi: 10.1038/nature02962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodrich LV, Milenkovic L, Higgins KM, Scott MP. Science. 1997;277:1109. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang ZJ, Ellis T, Markant SL, Read TA, Kessler JD, Bourboulas M, Schuller U, Machold R, Fishell G, Rowitch DH, Wainwright BJ, Wechsler- Reya RJ. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:135. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tremblay MR, Nesler M, Weatherhead R, Castro AC. Expert Opin. Ther. Patents. 2009;19:1039. doi: 10.1517/13543770903008551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Metcalfe C, de Sauvage FJ. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5057. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanton BZ, Peng LF. Molecular Biosyst. 2010;6:44. doi: 10.1039/b910196a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahindroo N, Punchihewa C, Fujii N. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:3829. doi: 10.1021/jm801420y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Low JA, de Sauvage FJ. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:5321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.27.9943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng JM, Curran T. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:493. doi: 10.1038/nrc3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Von Hoff DD, LoRusso PM, Rudin CM, Reddy JC, Yauch RL, Tibes R, Weiss GJ, Borad MJ, Hann CL, Brahmer JR, Mackey HM, Lum BL, Darbonne WC, Marsters JC, Jr, de Sauvage FJ, Low JA. N. Eng. J. Med. 2009;361:1164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LoRusso PM, Rudin CM, Reddy JC, Tibes R, Weiss GJ, Borad MJ, Hann CL, Brahmer JR, Chang I, Darbonne WC, Graham RA, Zerivitz KL, Low JA, Von Hoff DD. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:2502. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nat. Med. 2012;18:336. News in Brief. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yauch RL, Dijkgraaf GJ, Alicke B, Januario T, Ahn CP, Holcomb T, Pujara K, Stinson J, Callahan CA, Tang T, Bazan JF, Kan Z, Seshagiri S, Hann CL, Gould SE, Low JA, Rudin CM, de Sauvage FJ. Science. 2009;326:572. doi: 10.1126/science.1179386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang J, Hui C. Dev. Cell. 2008;15:801. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen W, Ren XR, Nelson CD, Barak LS, Chen JK, Beachy PA, de Sauvage F, Lefkowitz RJ. Science. 2004;306:2257. doi: 10.1126/science.1104135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Lu J, Bond MC, Chen M, Ren XR, Lyerly HK, Barak LS, Chen W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.U.S.A. 2010;107:9323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910712107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Lu J, Mook RA, Jr, Zhang M, Zhao S, Barak LS, Freedman JH, Lyerly HK, Chen W. Toxicol. Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs165. accepted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daiss B. Office of Pesticide Programs, United States Environment Protection Agency. Reregistration Case No.: 2525. 2010

- 31.Horton MK, Rundle A, Camann DE, Boyd Barr D, Rauh VA, Whyatt RM. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e699. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudel RA, Camann DE, Spengler JD, Korn LR, Brody JG. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003;37:4543. doi: 10.1021/es0264596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudin CM, Hann CL, Laterra J, Yauch RL, Callahan CA, Fu L, Holcomb T, Stinson J, Gould SE, Coleman B, LoRusso PM, Von Hoff DD, de Sauvage FJ, Low JA. N. Eng. J. Med. 2009;361:1173. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oakley RH, Laporte SA, Holt JA, Barak LS, Caron MG. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:32248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen JK, Taipale J, Young KE, Maiti T, Beachy PA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:14071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182542899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen W, Barak L, Lyerly HK, Wang J. WO2009154739A2. 2009:67.

- 37.Pan S, Wu X, Jiang J, Gao W, Wan Y, Cheng D, Han D, Liu J, Englund NP, Wang Y, Peukert S, Miller-Moslin K, Yuan J, Guo R, Matsumoto M, Vattay A, Jiang Y, Tsao J, Sun F, Pferdekamper AC, Dodd S, Tuntland T, Maniara W, Kelleher JF, Yao Ym, Warmuth M, Williams J, Dorsch M. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:130. doi: 10.1021/ml1000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taipale J, Chen JK, Cooper MK, Wang B, Mann RK, Milenkovic L, Scott MP, Beachy PA. Nature. 2000;406:1005. doi: 10.1038/35023008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wechsler-Reya RJ, Scott MP. Neuron. 1999;22:103. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oro AE, Higgins K. Dev. Biol. 2003;255:238. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li JJ, Shanmugasundaram V, Reddy S, Fleischer LL, Wang ZQ, Smith Y, Harter WG, Yue WS, Swaroop M, Li L, Ji CX, Dettling D, Osak B, Fitzgerald LR, Conradi R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:4932. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiang C, Swan RZ, Grachtchouk M, Bolinger M, Ying LTT, Robertson EK, Cooper MK, Gaffield W, Westphal H, Beachy PA, Dlugosz AA. Dev. Biol. 1999;205:1. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang LC, Liu ZY, Gambardella L, Delacour A, Shapiro R, Yang JL, Sizing I, Rayhorn P, Garber EA, Benjamin CD, Williams KP, Taylor FR, Barrandon Y, Ling L, Burkly LC. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2000;114:901. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paladini RD, Saleh J, Qian C, Xu GX, Rubin LL. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005;125:638. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tao HY, Jin QH, Koo DI, Liao XB, Englund NP, Wang Y, Ramamurthy A, Schultz PG, Dorsch M, Kelleher J, Wu X. Chem. Biol. 2011;18:432. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dijkgraaf GJP, Alicke B, Weinmann L, Januario T, West K, Modrusan Z, Burdick D, Goldsmith R, Robarge K, Sutherlin D, Scales SJ, Gould SE, Yauch RL, de Sauvage FJ. Cancer Res. 2011;71:435. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim J, Lee JJ, Kim J, Gardner D, Beachy PA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:13432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006822107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee MJ, Hatton BA, Villavicencio EH, Khanna PC, Friedman SD, Ditzler S, Pullar B, Robison K, White KF, Tunkey C, Leblanc M, Randolph-Habecker J, Knoblaugh SE, Hansen S, Richards A, Wainwright BJ, McGovern K, Olson JM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114718109. IPI-926 is a first generation inhibitor that structurally resembles cyclopamine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kinzel O, Alfieri A, Altamura S, Brunetti M, Bufali S, Colaceci F, Ferrigno F, Filocamo G, Fonsi M, Gallinari P, Malancona S, Hernando JIM, Monteagudo E, Orsale MV, Palumbi MC, Pucci V, Rowley M, Sasso R, Scarpelli R, Steinkuhler C, Jones P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:4429. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.