Introduction

The aim of this review is to present a detailed account of all published synthetic approaches toward the [3.3.1] bridged bicyclic class of phloroglucinol natural products most famously represented by hyperforin,1 a key ingredient in the commonly used extracts of St. Johns wort. In 2006, Grossman and Ciochina published the first review focused on this class of natural products.2 Their review comprehensively and thoughtfully discussed the remarkable structural diversity of this class, varied biological activities and a brief discussion of synthetic routes disclosed at that point. We refer the reader to Grossman’s review for a more detailed discussion regarding the isolation, structural elucidation and biological activity of the natural products presented in this report. In the last five years there has been a significant increase in published reports focused on creatively assembling members of this natural product family, which is why we consider the focus of this Tetrahedron Report both timely and hopefully valuable for the synthetic community.

Although the structure of hyperforin and many of its exciting biological functions have been known for some time now, it is interesting to note that the first synthetic efforts toward hyperforin (1, Scheme 1) were not reported until early 2005 and the first synthetic studies toward any member of this class were reported only in 1999. The target in this continuously growing natural product class that initially captured the attention of the synthetic community was garsubellin A (2), whose structure was first reported in 1998.3 In the twelve years that followed, nemorosone4 (3), clusianone5 (4) and hyperforin have emerged as additional popular synthetic targets from this natural product family. Teams of synthetic chemists from around the world have vigorously tackled these targets as reflected by the fact that since 1999, more than fifty papers have been published that detail novel approaches toward the total synthesis of these compounds and their unique bicyclic cores. As is evident from Scheme 1, these four natural products share many structural features in addition to the common [3.3.1] bicycle trione core. Their structural variability is mainly observed in the different degrees of prenylation (three or four), position (C3 or C5) and structure (isopropyl or phenyl) of the acyl group and the degree of oxidation (garsubellin A). These are not only non-trivial synthetic differences, but the effect on biological function can vary significantly.

Scheme 1.

Structures of Hyperforin, Garsubellin A, Nemorosone and Clusianone.

As graphically summarized in Scheme 2 the structures of these natural products and their diverse range of promising biological properties have inspired many researchers and resulted in the birth of a number of creative approaches for constructing their unique [3.3.1] bicyclic core. Shown in Scheme 2 are the names of team leaders, timeline of their published contributions along with a comprehensive list of the strategic reaction types these researchers chose to close the last bond of the bicyclic core. This list reveals that certain ring closures have been more popular than others, such as the Effenberger, aldol and Michael cyclization reactions. In total, these researchers have chosen seven different bonds or a combination of bonds to disconnect. The C1-C2 bond has been constructed employing aldol and Michael reactions in addition to a manganese mediated 6-endo cyclization reaction. The C3-C4 bond was formed using a metathesis reaction. The C4-C5 bond has been formed using a [3+2] cycloaddition as well as successful palladium mediated, aldol and pinacol cyclization strategies. The C5-C6 bond selenocyclization disconnection by Nicolaou6 was the first reported strategy toward this natural product class. A number of other researchers have also chosen to tackle this same bond to close the core. These C5-C6 approaches are also represented by halocyclizations, metal mediated cyclizations and Michael reactions. In addition to these four single bond disconnections many researchers have chosen to build the core using strategies that form two C-C bonds in a single pot. The first such reported tandem bond forming disconnection, the Effenberger cyclization, first reported by the Stoltz7 team to form both C1-C2 and C4-C5 bonds in one pot, has become one the more popular disconnections for this class of molecules. These two bonds have also been constructed in tandem using Michael/aldol, Robinson and radical cascade approaches. Finally, the C2-C3/C4-C5 and C5-C6/C8-C1 have been made in one pot employing a rhenium and Michael/Michael cyclization cascades respectively.

Scheme 2.

Strategies for construction of the [3.3.1] Bicyclic Core.

Although the contents of this review can be organized in several ways we decided to center sections of the review on authors and to present within these sections all of the author’s contributions to date. Furthermore, we selected to arrange these sections in order of the timeline of the first disclosure by each author.

1. Nicolaou’s Approaches to Garsubellin A and Hyperforin

The first approach toward this natural product family was reported by Professor K. C. Nicolaou and his team.6 He selected garsubellin A (2) as his primary target (Scheme 3) with the expectation that the final synthetic route could later be slightly modified to access other similar target structures. Nicolaou’s route centered on rapidly assembling the [3.3.1]-core by forming the C5-C6 bond employing an intramolecular union between a prenyl group and β-keto ester moiety. This they envisioned being accomplished using a Lewis acid mediated selenocyclization reaction, with the enolacetate shown in Scheme 3 serving as the cyclization precursor.

Scheme 3.

K.C. Nicolaou’s 1999 Approach Toward the Garsubellin A Bicyclic Core.

Nicolaou’s route commenced with the known prenylation8 of readily available dihydroresorcinol (5, Scheme 4). The resulting dione (6) was then selectively C-alkylated with ethyl bromoacetate. Both ketones (7) were next reduced to form a meso-diol. Desymmetrization was accomplished by lactonizing one of the alcohols. Chromium mediated oxidation of 8 set the stage for formation of a β-ketoester using methyl cyanoformate,9 which was then capped as an enolacetate (10). The key selenocyclization was nicely accomplished by adapting Ley’s original procedure10 using a modified selenium reagent introduced by Professor Nicolaou11 20 years earlier. This excellent reaction allowed very rapid construction of an adequately functionalized core (11) containing bridgehead substitution and the C6 dimethyl quaternary center. Core functionalization was initialized by selectively reducing the bridgehead ketone and derivatizing the resulting alcohol to serve as a radical acceptor. This was accomplished by forming a vinylogous sulfonate, obtained by treating an alkoxide with 12.

Scheme 4.

K.C. Nicolaou’s 1999 Synthetic Approach Toward Garsubellin A (Part I).

Further decoration of the bicyclic core was initiated following Evans’ radical strategy.12 This intramolecular 6-exo radical cyclization approach ensured stereocontrolled formation of the critical C7 stereocenter (13→14, Scheme 5), concomitantly providing the required functionality to complete the installation of the prenyl moiety. Exhaustive reduction of the two carboxylate groups and protection of the less hindered one as a bulky silyl ether (15) set the stage for introduction of the isopropyl group. Selective primary alcohol oxidation was accomplished with TEMPO. Direct addition of an isopropyl Grignard to the aldehyde failed and resulted instead in hydride delivery. Nicolaou’s team solved this challenge by employing isopropenyl magnesium bromide to provide allylic alcohol 16. This stereoselective addition was accompanied by elimination of the ether beta to the sulfonyl group. One pot reduction of the two double bonds was not successful and instead a three step sequence using Adams catalyst to selectively reduce the propenyl group followed by carbonate formation and Pd/C catalyzed reduction of the conjugated sulfone was developed (17). Next the C2 alcohol was converted to a ketone and then turned into an enone (18) using SeO2 under forcing conditions. This enone they envisioned could be used to install both the C3 alkyl group as well as oxidize the C4 carbon using a very ambitious late stage [2+2]/Baeyer-Villiger sequence. This proposal was indeed realized, as dimethoxyethylene was first selectively added to 18 and deprotected to afford cyclobutanone 19 in moderate yields. As proposed, the Baeyer-Villiger oxidation proceeded favorably to install the desired C4-hydroxy functionality.

Scheme 5.

K.C. Nicolaou’s 1999 Synthetic Approach Toward Garsubellin A (Part II).

This 24 step sequence by Nicolaou is memorable for its non-obvious introduction of many of the functional group. The reaction highlights of this route are the selenocyclization, radical cyclization, [2+2] cycloaddition and Baeyer-Villiger steps. Although functional groups seem to be in place to enable advancement of their most advanced intermediate (20) to garsubellin A (2) no further reports have emerged yet in the literature.

A few years later, the Nicolaou group proposed to access the bicyclic core of hyperforin (1, Scheme 6) using an acid-catalyzed Michael/Aldol cascade.13 Their proposal was inspired by success in using enamines14 in building such systems and numerous literature examples that suggested the initial Michael step between a 1,3-diketone and an acrolein could readily be realized using an acid catalyst. This convergent route, which would allow formation of both the C1-C2 and C4-C5 bonds in a single pot, provided opportunities to start with relatively simple starting materials.

Scheme 6.

K.C. Nicolaou’s 2005 Approach Toward the Hyperforin Bicyclic Core.

Nicolaou’s hyperforin model construction studies began with a Katritzky coupling between 2-methylcyclohexanone and acyl triazole (22, Scheme 7). The product (23) readily underwent the proposed Michael/Aldol cascade in the presence of methacrolein and catalytic amounts of triflic acid to afford bicyclic dione 24 in good yield as a mixture of two diastereomers. Upon further inspection of this cascade, which Nicolaou’s group demonstrated as an approach for accessing five other [n.3.1] bicyclic systems, they found that a number of other metal triflates catalyzed this transformation with similar success (Bi(OTf)3, Sn(OTf)2, TMSOTf and AgOTf for example). Oxidation of alcohol 24 afforded the trione (25), which was converted in a classic two step sequence to enone 27.

Scheme 7.

K.C. Nicolaou’s 2005 Synthetic Approach Toward Hyperforin.

Although this route was not further explored toward hyperforin it serves as an excellent example of how the bicyclic core of this family of natural products can be quickly assembled with the appropriately designed synthetic cascade.

2. Shibasaki’s Approaches to Garsubellin A and Hyperforin

Professor Shibasaki has been one of the more prolific contributors to this area, with his primary focus on the total synthesis of garsubellin A (2) and hyperforin (1). The following sections detail the evolution of his approaches that eventually led to successful total syntheses of both natural products.

Shibasaki’s approach to the bicyclic core is outlined in Scheme 8. He envisioned rapidly accessing the natural product core by coupling together in one pot a 1,3-diketone with appropriately functionalized acrylate fragment to enable a Dieckman reaction to proceed immediately followed by an intramolecular Michael addition/elimination reaction. It was expected that the doubly stabilized anion at C5 would first attack the activated acrylate ester and that the resulting tricarbonyl product would close to form the bicylic core via addition of the C1 anion to the olefin terminus in a 6-endo Michael fashion. One of the challenges of this attractive disconnection is to be able to trap the acrylate moiety on the face of the enolate that matches the chirality of the secondary alcohol containing tether and thus in matches the asymmetric plans for the natural products.

Scheme 8.

M. Shibasaki’s 2002 Approach Toward the Garsubellin A Bicyclic Core.

Shikasaki’s first approach was initiated by the conjugate addition of methyl cuprate to enone 28 (Scheme 9) and trapping the ensuing copper enolate with isobutyraldehyde.15 The resulting secondary alcohol was capped with a silyl protecting group (29). Ketone 29 was next alkylated with ethyl bromoacetate and the ester group was selectively reduced with DibalH to form aldehyde 30. In order to install the rest of the oxygenated sidechain, methyl ketone 31 was formed as 1.3:1 mixture of diastereomers via a cyanohydrin formation and addition of methyl cuprate to the nitrile. Grignard addition and acetonide protection afforded 32, which was then primed for testing of the key cascade by deprotection of the silyl ether and oxidation of the resulting secondary alcohol. This ten step racemic sequence afforded an almost equimolar mixture of 33 and 34. This is where things turned to the worse for Shibasaki and his team. Under no conditions tried was the Dieckman/Michael cascade realized when 33/34 were deprotonated and treated with acrylate 35. To complicate things even further, they observed that the C1 anion reacted instead of the doubly stabilized C5 anion. This was not the only wrench that was thrown into their plans as analysis showed that Michael addition/elimination proceeded as the preferred C-C bond formation path instead of the expected Dieckman addition. To add to the bad news, their detailed stereochemical analysis revealed that they obtained the undesired epimer in the C-C bond forming step (36). Not discouraged by these challenges the Shibasaki group decided to craft a new synthetic plan to the bicyclic core that would take advantage of the enol lactone, while still stay true to their originally proposed endgame plans. They envisioned that the enol lactone could be unraveled to an aldehyde and then subjected to an intramolecular aldol union with the dicarbonyl group. After significant experimentation the Shibasaki group developed a nice one pot procedure that built on their experimental insights and allowed them to advance the mixture of 33 and 34 to enol lactone 36 in good yield. Although the epimer 36 was advanced to the hydroxyl epimer of C7-deprenyl garbsubellin by the Shibasaki group, the discussion that follows will focus on how they tackled forming the correct epimer in the dianion union with 35.

Scheme 9.

M. Shibasaki’s 2002 Synthetic Approach Toward Garsubellin A (Part 1).

Toward that end, Shibasaki first noticed that functionalization of the secondary alcohol had pronounced effects on the epimer ratio.16 He speculated that changing the diol protection group (acetonide) might address this challenge. Remarkably his team learned that when the acetonide (33 and 34, Scheme 9) was replaced with a cyclic carbonate (37 and 38, Scheme 10) this epimer ratio could be improved greatly in favor of the desired epimer (40). At this point, it was decided to mask the conjugated olefin as a hydroxyl group that could be later eliminated to allow a late stage intramolecular Wacker oxidation to be tested. This was accomplished by the conjugate addition of a specialized silyl group, which predictably added opposite to the large adjacent oxygenated sidechain. Tamao oxidation17 ensured conversion of the silyl-carbon bond to a hydroxyl group, which was then silylated with TESOTf to afford lactone 41. To set the stage for the intramolecular aldol cyclization to form the bicyclic core of garsubellin A, the Shibasaki team chose to form a thioester that could be selectively reduced to the desired aldehyde (42) using Fukuyama’s reduction protocol,18 which is reminiscent of the Rosenmund reaction. Fortunately, the aldol cyclization proceeded smoothly. The newly formed alcohol was rapidly oxidized and the β-silyl ether eliminated (43). Hydrolysis of the carbonate set the stage for the proposed intramolecular Wacker oxidation, which proceeded favorably to form 44. Completion of the synthesis of C7-deprenyl garsubellin A (46) was completed by first installing a vinyl iodide (45), which was then cross-coupled in modest yields with prenyl stannane in the presence of PdCl2(ddpf) as a catalyst.

Scheme 10.

M. Shibasaki’s 2002 Synthetic Approach Toward Garsubellin A (Part 2).

In these two reports, Shibasaki presents a synthetic route for accessing a garsubellin A structure only lacking the 7-prenyl group. This he accomplishes in 24 steps starting with 3-methyl cyclohexenone. The most notable features of his route are the Michael addition to 35, the intramolecular aldol and Wacker cyclization reactions. Unfortunately for Shibasaki and his team this route turned out to be a dead end for accessing garsubellin A as the key aldol cyclization step failed under all conditions tried when the C7-prenyl group was in place. A detrimental retro-aldol path was believed to be one of the main impediments.

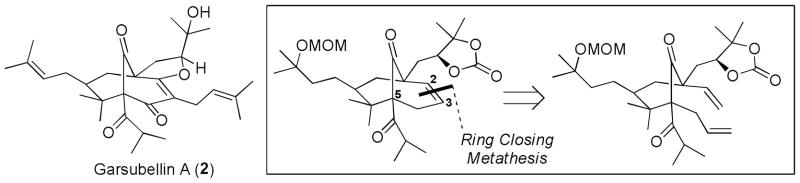

Not discouraged by the unforeseen aldol cyclization roadblock, the Shibasaki group modified their retrosynthetic sequence and chose instead to test the feasibility of forming the C2-C3 bond in the key cyclization step (Scheme 11).19 They crafted a new plan that took advantage of many of the synthetic solutions and lessons learned during their aldol approach. A late stage cyclization step was envisioned, bringing a vinyl and allyl terminus together using a ruthenium catalyzed ring closing metathesis reaction. This robust reaction would not be limited by the reversibility challenges of the failed aldol cyclization.

Scheme 11.

M. Shibasaki’s 2005 Approach Toward Garsubellin A.

The new route was initiated with a Stork Danheiser sequence, which was used to transform vinylogous ester 47 into prenylated enone 48 in excellent yields (Scheme 12). Using lessons from their earlier route, the isopropyl acyl group of garsubellin A was introduced using an efficient one pot cuprate mediated conjugate addition followed by trapping with isobutyraldehyde and protection of the secondary alcohol with a stable triisopropyl silyl protecting group (49). Foreseeing potential unwanted ring closing and cross metathesis pathways, the Shibasaki group chose at this point to protect the newly installed prenyl group by masking it as a tertiary alcohol (50). This was accomplished using Mukaiyama’s20 cobalt catalyzed hydration protocol. The resulting tertiary alcohol was then protected as a MOM-ether. Next, focus turned to alkylation of C1. Enolization with KHMDS and trapping with prenyl bromide was followed by a stereoselective aldol reaction with acetaldehyde (52). Completion of the vinyl fragment needed for the ring closing metathesis was accomplished in excellent yield using Martin sulfurane21 dehydration agent. Chemoselective dihydroxylation of the prenyl group was accomplished using AD-mix-α. Unfortunately this oxidation step was non-stereoselective (1:1 dr). Worse yields were obtained without any improvements in stereoselectivity when AD-mix-β was used. With the desired sidechain oxygenation accomplished, the diol was temporarily masked as a cyclic carbonate (54) by treatment with triphosgene in pyridine.

Scheme 12.

M. Shibasaki’s 2005 Total Synthesis of Garsubellin A (Part 1).

With C1-functionalization complete, the Shibasaki group turned their attention to allylating C5 (Scheme 13). Deprotection of silyl ether 54 and oxidation of the secondary alcohol was accmoplished using pyridinium dichromate in the presence of celite. C4-Allylation of 1,3-diketone 55 could not be done directly, but was instead accomplished using a two step high yielding strategy that utilized O-alkylation followed by a thermal Claisen rearrangement. Gratifyingly, the proposed ring closing union between the C1-vinyl group and the C4-allyl group proceeded with excellent yield in the presence of 20 mol% of Hoveyda’s modification (57, GH-II) of Grubbs’ second generation ruthenium catalyst. Allylic oxidation of the newly formed endocyclic olefin to the corresponding enone was successfully done using Barton’s22 selenium oxidation procedure. Deprotection of the MOM-ether proceeded uneventfully to afford 59. Shibasaki now revisited the successful intramolecular Wacker oxidation disclosed in his 2002 approach. Following carbonate hydrolysis, oxidative cyclization to form the tetrahydrofuran group was accomplished employing Na2PdCl4 as catalyst and t-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) as oxidant (60). The final steps needed to complete the first total synthesis of garsubellin A (2) again took advantage of previous developments in the Shibasaki lab. Iodination of the enone moiety was done using iodine in the presence of ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN). Dehydration of the tertiary alcohol to reform the desired C7-prenyl group proceeded in high yield with p-toluenesulfonic acid. The last step in the total synthesis, palladium catalyzed Stille prenylation of C3 proceeded to form garsubellin A, albeit in modest 20% yield.

Scheme 13.

M. Shibasaki’s 2005 Total Synthesis of Garsubellin A (Part 2).

Shibasaki’s total synthesis of garsubellin A was the first total synthesis accomplished of any member of the [3.3.1] phloroglucinol family of natural products. Highlights of his route include nice applications of the Claisen, ring closing metathesis and intramolecular Wacker cycliczation reactions. Conversion of ester 47 to racemic garsubellin A (2) was achieved in 23 steps.

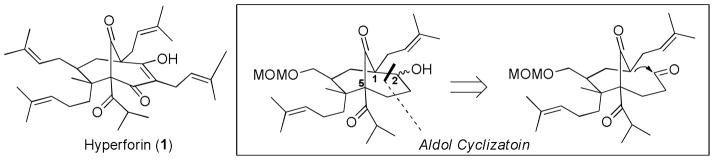

Following the success of their total synthesis of garsubellin A, the Shibasaki team wondered if modifications could be made to their route that could also serve as a solution for completing a total synthesis of hyperforin (1). With both garsubellin A and hyperforin containing a C7-prenyl group and hyperforin an additional prenyl substituent at C6, the Shibasaki group was concerned with downstream metathesis challenges, which is why they decided to revisit the aldol disconnection. They had demonstrated earlier (2002) that such an aldol disconnection could be realized in forging the C-C bond between C4 and C5 (42, Scheme 10), but to their disappointment the aldol cyclization could not be realized for substrates containing a C7-substituent. Given these results and challenges they were confronted with, they wondered if the aldol strategy could be used to form the C1-C2 bond instead of the C4-C5 bond (Scheme 14).23 Their new aldol route took advantage of advanced synthetic intermediates from Shibasaki’s program as well as making the most of clues and lessons learned from their earlier attempts, and so devised sequence that allowed them to rapidly test the feasibility of their C1-C2 cyclization proposal.

Scheme 14.

M. Shibasaki’s 2007 Approach Toward the Garsubellin A Bicyclic Core.

Efforts to put this new disconnection to the test commenced with ketone 50 (Scheme 15). The goal was to utilize an allylation/Claisen rearrangement sequence again to install the C5 allyl group, which would then be transformed into an aldehyde. Toward that end, ketone 50 was prenylated and C1 of the resulting product (61) epimerized. Silyl deprotection of 62 was then followed by chromium mediated oxidation of the resulting alcohol and an enol-ether O-allylation. When 63 was rearranged, allylated 1,3-diketone 64 was obtained in high yield and excellent diastereoselectivity. This nice solution allowed them to move forward and test the key cyclization step. Hydroboration of the allyl group and oxidation of the primary alcohol afforded aldehyde 65. Gratifyingly, the proposed aldol cyclization was realized in the presence of sodium hydroxide in ethanol. The aldol product was then quickly oxidized to triketone 66.

Scheme 15.

M. Shibasaki’s 2007 Approach Toward Garsubellin A.

With the success of the latest aldol disconnection the Shibasaki group decdided to tackle the more complex hyperforin (1), which, in addition to the common substitution features it shares with garsubellin A (2), contains a quaternary stereocenter at C6 instead of a gem-dimethyl group. This additional stereocenter further complicates things for any synthetic planning and it remained to be seen if the lessons from their aldol cyclization studies could be successfully adopted for this system (Scheme 16). Thus Shibasaki team launched a campaign to complete the first total synthesis of hyperforin.24,25 Furthermore, they set out to completely overhaul the synthesis of the aldol cyclization precursor employing a robust asymmetric iron catalyzed Diels-Alder cycloaddition, which they had developed and hoped to use for both garsubellin A and hyperforin.26

Scheme 16.

M. Shibasaki’s 2010 Approach Toward Hyperforin.

Shibasaki’s new approach started with carboxylation of known alkyne 6727 (Scheme 17). Tetrasubstituted allylic alcohol 69 was obtained in three steps from 68. This sequence utilized a methyl cuprate conjugate addition and trapping of the resulting enolate with acetyl bromide. Exhaustive reduction of the conjugated β-keto ester and selective silylation of the primary alcohol furnished 69. The diene (70) needed for the asymmetric Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction was prepared using tetrapropylammonium perruthenate (TPAP) in the presence of NMO and the resulting ketone was then converted to silyl enol ether by treatment with TIPSOTf and Hünig’s base. The Diels-Alder union of diene 70 and dienophile 71 proceeded nicely in the presence of an in situ formed cationic iron complex derived from complexation of FeBr3 and chiral pybox ligand 72. This outstanding transformation, developed by the Shibasaki group, resulted in the formation of cycloadduct 73 containing the two adjacent non-bridgehead stereocenters of hyperforin in excellent yield and with outstanding enantioselectivity. For this reaction the Shibasaki group used ligand 72, which is made from inexpensive (R)-4-hydroxyphenylglycine. This choice of chiral ligand would afford the enantiomer of hyperforin.

Scheme 17.

M. Shibasaki’s 2010 Total Synthesis of ent-Hyperforin (Part 1).

Following the success of their catalytic asymmetric Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction the silyl groups of 74 were removed to provide hydroxyl ketone 75 (Scheme 18). Turning their attention toward selective 1,3-functionalization of the ketone, the Shibasaki team chose to temporarily protect the primary alcohol 75 and mask the ketone as silyl enol ether. Mild methanolysis of the ethereal silyl group unraveled alcohol 76, which set the stage for introduction of the isopropyl group while keeping the keto group from interfering. Oxidation using Professor Ley’s TPAP procedure and addition of the 2-lithiopropane to the resulting ketone completed the installation of the isopropyl fragment. Deprotection of the silyl enol ether with TBAF revealed ketone 77, which allowed introduction of the adjacent prenyl group. Temporarily capping the secondary hydroxyl group with a trimethylsilyl group sets the stage for the prenylation (78) using LDA and HMPA as a co-solvent. From the previous aldol cyclization model system (Scheme 15) the Shibasaki team had learned that the stereochemistry of the prenyl group had significant impact on the stereochemical outcome when incorporating the quaternary allyl group via a Claisen rearrangement. Taking advantage of this insight, the newly installed C1-prenyl group was epimerized with LDA. Construction of the Claisen substrate was completed via a three step sequence involving, desilylation, oxidation and O-allylation using NaHMDS and allyl bromide (79). Gratifyingly, the insights gained from earlier synthetic efforts translated productively in the hyperforin synthesis thus affording the Claisen rearrangement product in excellent yield and a 12:1 diastereoselectivity favoring the desired diastereomer. Completion of the aldol cyclization substrate was accomplished by selective hydroboration of the allyl group and oxidation of the primary hydroxyl group to aldehyde 80 with Dess-Martin periodinane.

Scheme 18.

M. Shibasaki’s 2010 Total Synthesis of ent-Hyperforin (Part 2).

The advanced system’s success also translated well for the key aldol cyclization step (81, Scheme 19). Conversion of the MOM methylene ether to hyperforin’s non-bridgehead prenyl group was initiated with acid catalyzed deprotection of the MOM-protecting group in methanol. Unfortunately, this deprotection step was accompanied by methanol addition to the homo prenyl group. This unforeseen turn of events turned was not without benefits as it ensured that the homo-prenyl would not interfere with later cross metathesis events. Next, the primary alcohol was oxidized and the product treated with vinylmagnesium bromide. The resulting allylic alcohol (83) was acylated and then reductively transposed in the presence of Pd(PPh3)4 and ammonium formate following Tsuji’s procedure.28 The prenyl group synthesis was completed as described in the approach to garsubellin A, using a cross methathesis strategy employing ruthenium catalyst 57 and 2-methyl-2-butene. With most substitutions mostly complete, the Shibasaki team focused on finding solutions for constructing the prenylated 1,3-dione system. The first step toward that end was accomplished using Saegusa’s29 palladium-mediated conversion of silyl enol ether to enone (85). With the enone in hand, a variety of conjugate additions using a number of different heteronucleophiles aimed toward installing a hydroxy functionality at C2 were tried. Unfortunately, all these attempts were unsuccessful. Following careful assessment of their options, it was decided to attempt derivatization of the existing carbonyl group and use instead an intramolecular allylic rearrangement to incorporate the second hydroxy group. The first step toward this new goal was accomplished by selective 1,2-reduction of the enone and forming a xanthate from the alcohol (86).

Scheme 19.

M. Shibasaki’s 2010 Total Synthesis of ent-Hyperforin (Part 3).

Having installed the allylic xanthate, the stage was set for testing the [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement. Thus, heating 86 (Scheme 2) afforded a single product in high yield. Surprisingly, analysis revealed that instead of the desired Claisen rearrangement taking place the xanthate cleanly underwent a [1,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement to form 87. With this unexpected outcome, the Shibasaki group needed to return to the drawing board. The third proposed plan to install the hydroxy group needed to install the 1,3-dicarbonyl group involved a vinylogous Pummerer rearrangement and trapping of the intermediate thionium intermediate with an appropriately matched hydroxy nucleophile. With this new plan, the xanthate needed to be first transformed to sulfoxide 88, which was realized in two steps by treatment with a lithium thiolate, trapping with methyl iodide and oxidation of the sulfide with sodium perborate. This new strategy turned out to be a success, with the Pummerer reaction proceeding nicely in the presence of trifluoroacetic anhydride, the thionium ion being trapped with trifluoroacetate and sodium carbonate workup ensuring hydrolysis of the trifluoroacetate (89). It is quite remarkable to note that the vinylogous Pummerer rearrangement proceeded preferentially over the normal Pummerer path, which would have resulted in formation of unwanted enone 85. Consecutive oxidations of the allylic alcohol and the sulfide groups afforded vinylogous sulfoxide 90. Deprotection of the homoprenyl substituent was accomplished by Amberlyst-15 dehydration of the tertiary ether. Conjugate addition with deprotonated allyl alcohol proceeded with accompanying elimination of the sulfoxide group (91). Allyl functionalization was done employing a palladium catalyzed allylic transposition and protection of the enol with an acyl group. Cross metathesis using ruthenium catalyst 57 proceeded to form the desired prenyl group, albeit in poor 34% yield. The first total synthesis of ent-hyperforin (1) was completed by hydrolyzing the enol acetate.

This heroic first total synthesis of hyperforin by the Shibasaki group was accomplished in 50 steps from 67. The main reaction highlights of this route include a catalytic asymmetric Diels-Alder reaction, stereoselective Claisen-rearrangement, intramolecular aldol cyclization, cross metathesis and a Pummerer rearrangement.

Although Shibasaki’s first tandem Dieckmann/Michael route toward the bicyclic core failed, he has shown that three other disconnections can be used to construct the core: 1) aldol cyclization, 2) ring closing metatathesis and 3) aldol cyclization. Their ring closing metathesis approach served as one of the key steps in the first total synthesis of garsubellin A (2), while the aldol cyclization enabled the first total synthesis of hyperforin (1).

3. Stoltz’s Approach to Garsubellin A

The Stoltz group made one of the earliest synthetic contributions toward this class of molecules.7 Their synthetic proposal relied on employing the Effenberger reaction30 to couple malonyl dichloride and an appropriate silyl enol ether (Scheme 21). This convergent approach not only forms both C1-C2 and C4-C5 in one pot, but also installs the challenging 1,3-dione moiety. The main question for this attractive approach was whether the Effenberger reaction could be accomplished using a cyclohexane silyl enol ether containing both alkyl groups needed for the bridgehead of the bicyclic core. The Stoltz group set its sights on garsubellin A (2) as their primary target of pursuit.

Scheme 21.

B. M. Stoltz’s 2002 Approach Toward the Garsubellin A Bicyclic Core.

Stoltz’s approach toward testing the feasibility of his retrosynthetic proposal was initiated with a Stork-Danheiser sequence, 31 involving alkylation of vinylogous ester 92 with prenyl bromide, methyl lithium addition and elimination to afford enone 94 (Scheme 22). Conjugate methylcuprate addition installs the gem-dimethyl group (95). Selective silyl enol ether formation completed the synthesis of the model nucleophile 96 needed for the key Effenberger cyclization. With only a single simple precedent for forming such bicyclic frameworks, the Stoltz group set out to identify the optimal conditions for forming 97. After much experimentation, they demonstrated that aqueous KOH under biphasic conditions were the best match, affording bicyclic trienone 97 in 36% isolated yield. Following this success in realizing the proposed tandem cyclization approach, it was decided to use the model system to explore installation of the C3 prenyl group. Esterification of vinylogous acid 97 with allyl alcohol furnished allyl ester 98. A Claisen rearrangement was used to add the allyl group to C3 and the ensuing free acid was esterified with diazomethane (99). Completion of the prenyl moiety was accomplished using Grubbs second generation catalyst (100) in the presence of 2-methyl-2-butene. This example was the first target application of a remarkably powerful new approach32 for the synthesis of prenyl groups. Saponification of the methyl ester afforded acid 101, Stoltz’s most advanced intermediate.

Scheme 22.

B. M. Stoltz’s 2002 Synthetic Approach Toward Garsubellin A.

The Stoltz group’s strategy is a very efficient approach to the core and the first successful route that constructs two C-C bonds in the key core forming step. The optimal application of this approach would be to couple malonyl chloride with an enol ether containing both bridgehead substituents. Toward that end, the Stoltz group demonstrated in a model system, using two methyl groups as sidechain surrogates, that this transformation could indeed be realized in 25% isolated yield. Stoltz’s use of the Effenberger cyclization to form the core and his realization that Grubbs’s cross metathesis prenyl approach would be a good match for targeting garsubellin A (2) has not gone unnoticed as many researchers have adapted one or both of these disconnections in their own studies.

4. Young’s Approach to Garsubellin A

The fourth lab to publish their synthetic approach, following the contributions from the Nicolaou, Shibasaki and Stoltz labs, was that of Professor Young from the University of Tennessee (Scheme 23). Their novel approach relied on applying an intramolecular [3+2] cycloaddition between an allene and a nitrile oxide to close the bicylic framework by forming the C4-C5 bond and simultaneously installing the isopropyl acyl moiety. If successful, this would represent the first example of an intramolecular cycloaddition featuring those two reactive partners.

Scheme 23.

David G. J. Young’s 2002 Approach Toward the Garsubellin A Bicyclic Core.

Young’s route began with a two step synthesis of exocyclic enone 103 (Scheme 24) following Johnson’s procedure.33 Selective 1,2-addition to the ketone was accomplished using a cerium alkyne, which was then followed by selective ozonolyzis of the styrenyl group to afford ketone 104. Reduction and carbonate formation with carbonyl diimidazole led to propargylic carbonate 105. The allene fragment needed for the key cycloaddition step was accessed by addition of lithium cuprate to the alkyne, and oxidation of the liberated secondary alcohol thus providing enone 106. Silyl enol ether formation (107) was followed by a titanium mediated Mukayama aldol union with dimethyl acetal 108, which completed the construction of the key cyclization precursor 109 as a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers. The Young group was delighted to learn that their proposed intramolecular cycloaddition could indeed be realized (110) by treating 109 with phenylisocyanate in refluxing benzene. A single bicyclic diastereomer (110) was formed in this key step. To further showcase the strengths of their new synthetic route, Young and his team quantitatively cleaved the N-O bond with Raney-Ni. This selective reduction step unraveled the desired isopropyl acyl fragment and liberated the C4 carbonyl in the form of an enamine (111).

Scheme 24.

David G. J. Young’s 2002 Synthetic Approach Toward Garsubellin A.

The Young group’s route is a creative and daringly features the first example of an intramolecular [3+2] cycloaddition using an allene as a dipolarophile and nitrile oxide as a 1,3-dipole. In this short sequence, the quaternary center at C6 is in place along with the isopropyl acyl group and appropriate oxidation state presence at C2, C4 and the bridgehead carbons. The only groups missing are the prenyl groups at C1, C3 and C7.

5. Kraus’ Approaches to Hyperforin, Nemorosone and Papuaforin

George Kraus and colleagues at the University of Iowa have explored several different approaches toward the [3.3.1] bicyclic core of the phloroglucinol family of natural products. Their initial approach34 (Scheme 25) made use of Professor Barry Snider’s excellent work detailing the unique and useful reactivity profile of manganese(III) mediated cyclizations.35 Using this strategy, the Kraus group envisioned forming the C1-C2 bond of hyperforin. Toward that end they chose to test the feasibility of this approach on the allylated β-ketoester shown.

Scheme 25.

G. A. Kraus’ 2003 Approach Toward the Hyperforin Bicyclic Core.

Kraus was able to rapidly test his proposal by first constructing known β-ketoester 113 in three steps via 112 following the work of Rothberg36 (Scheme 26). To his delight, Snider’s managese(III) cyclization conditions worked nicely to afford the sought after bicyclic core (114). Kraus decided to take advantage of this simple model system and use it to learn how to complete the synthesis of the C1-C3 region of hyperforin. After some experimentation a solution was identified, which entailed treating 114 with excess N-bromosuccinimide in the presence of catalytic amounts of AIBN in carbon tetrachloride. This approach furnished vinylogous acid bromide 115. Installation of the C3 allyl fragment was accomplished in two steps via a basic esterification of 115 with allyl alcohol and a Claisen rearrangement of the resulting ester (116) to afford 117.

Scheme 26.

G. A. Kraus’ 2003 Synthetic Approach Toward Hyperforin.

The highlights of this concise approach are the manganese(III) cyclization and the radical bromination step to install the challenging 1,3-dione group. In this same report, the Kraus group demonstrated that a 1,3-diketone, in the form of a phenacyl group, could also be advanced following this sequence. Being able to advance a 1,3-diketone broadened the target scope of this approach to also include natural products such as nemorosone (3).

Interestingly, in the same initial report the Kraus group also detailed an alternate strategy for accessing the bicyclic core (Scheme 27). This second more classical approach utilized an aldol cyclization to form the C1-C2 bond. An advantage of this approach would be quaternarty carbon substitution at both C1 and C5.

Scheme 27.

G. A. Kraus’ 2003 Second Approach Toward the Hyperforin Bicyclic Core.

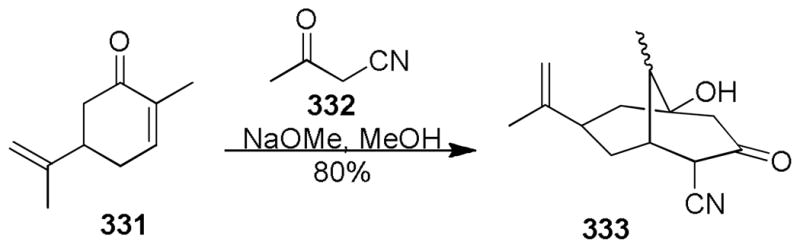

As before, the Kraus group chose to test their hypothesis on an easily accessible model system (120, Scheme 28). The aldol cyclization substrate was constructed in four steps from 2-methyl cyclohexanone (118). The first three steps followed Ender’s hydrazone procedure37 for installing acyl groups (119). Because Michael addition into acrolein proved quite troublesome, careful optimization studies identified sodium methoxide in methanol containing trace amounts of hydroquinone as the optimal conditions for forming 120. The proposed aldol cyclization was realized using hydrochloric acid in refluxing acetone. Oxidation of the alcohol with pyridinium dichromate (PDC) afforded trione 121. To make the most of their model system the Kraus group chose again to study the conversion of 121 to C1-C3 diketone 123. Following Saegusa’s silyl enol ether oxidation protocol Kraus had no problems forming 122. Unfortunately, all attempts to further oxidize enone 122 to diketone 123 were unsuccessful.

Scheme 28.

G. A. Kraus’ 2003 Second Synthetic Approach Toward Hyperforin.

The aldol cyclization approach from the Kraus group quickly assembles a reasonably well functionalized trione core (122) from simple starting materials. The base catalyzed Michael addition and acid mediated aldol cyclization steps are the highlights of this contribution from the Kraus lab.

In trying to advance more appropriately functionalized substrates using either the manganese(III) or aldol cyclization strategies highlighted above, the Kraus group ran into a series of obstacles. These challenges inspired them to go back to the drawing board and propose a daring Double-Michael cyclization strategy that would form both C1-C2 and C4-C5 bonds in one pot. This new strategy used lessons from important sulfone chemistry contributions from the labs of Professor Padwa.38 Nemorosone was chosen as their new target of interest to exercise this new approach.

Making use of advanced synthetic intermediate 112 (Scheme 30), produced in their earlier study, the Kraus group was able to quickly evaluate the synthetic potential of the newly proposed cascade. Methylation of 112 afforded cascade nucleophile 124. The Michael acceptor (125) was constructed in three steps from the diacetyl acetal of acrolein. Screening of bases and solvent soon suggested that the proposed Michael-Michael cascade would not be easily realized using these substrates. The first Michael addition/elimination step (126) was most successfully accomplished using potassium t-butoxide. Protecting the free enol in situ as a t-butyl carbonate enol was essential for obtaining 126 in high yields. The Second Michael step could then also be realized with potassium t-butoxide in 56% yield. The resulting diastereomeric hydroxyl-sulfone mixture (127) was then acylated (128) and reduced to form the C2-C3 olefin (129).

Scheme 30.

G. A. Kraus’ 2005 Synthetic Approach Toward Nemorosone.

Although the double-Michael cascade was not successful, the Kraus group was comforted by the fact that the Michael reactions could be accomplished in a stepwise manner. As with their other two approaches, this new strategy was not deemed suitable for completing total syntheses of the natural products.

Undeterred from the challenges encountered in his previous synthetic campaigns Kraus used those lessons to yet again go back to the drawing board and develop a route that could be advanced to complete a total synthesis. 39 For this new route, he aimed to complete the first total synthesis of papuaforin A40 (130, Scheme 31). Papuaforin A (130) contains a methyl group at C1 instead of a prenyl group found in both hyperforin (1) and garsubellin A (2). Furthermore, the C2 hydroxy group is connected to the C3-prenyl group in a cyclic pyran. In his latest approach, Kraus decided to form the C1-C2 bond of the bicyclic core last via a reductive coupling/cyclization strategy. This approach makes use of a similar reaction from Boeckman’s total synthesis of ceroplastol I.41

Scheme 31.

G. A. Kraus’ 2008 Approach Toward the Papuaforin A Bicyclic Core.

Kraus started his approach by repeating a procedure developed by Heathcock42 for converting dimedone (131) to ester 132 (Scheme 32). A Stork-Danheiser sequence then afforded enone 133 and Mander’s carboxylation procedure ensured a rapid and reliable five step route to 134 from dimedone.43 Conjugate addition of β-ketoester 134 to methyl acrylate was accomplished using potassium t-butoxide. Gratifyingly, Boeckman’s cyclization precedence proved successful and resulted in the formation of diol 135 in excellent yield as a mixture of diastereomers. Diol oxidation, silyl enol ether formation and radical bromination predictably afforded bromoenone 136. Sonogashira coupling with 2-methyl-3-butyn-2-ol ensured installation of the carbon functionalities found in the C3-sidechain of papuaforin A (130). Selective cis-reduction44 of the newly installed triple bond afforded hemiketal 138. Disappointingly, oxidative allylic transposition of the free hydroxyl group at C2 to form the C4-ketone using chromium based reagents failed.

Scheme 32.

G. A. Kraus’ 2008 Synthetic Approach Toward Papuaforin A.

Kraus’ twelve step synthesis of 138 from dimedone is very efficient and creative. To complete the first total synthesis papuaforin A (130) the Kraus group needs to find a way to transpose the allylic hemiketal (138) and convert the ester to an isopropyl ketone. The highlights of this route include a high yielding reductive cyclization, radical bromination and cis-selective alkyne reduction steps.

6. Grossman’s Approach to Nemorosone

Professor Grossman from the University of Kentucky was one of the early contributors to this area of research (Scheme 33).45 He envisioned a C1-C3 aldol disconnection to form the bicyclic core. His key cyclization would be performed with a densely functionalized enal containing useful handles for completing the C2-C4 portion of nemorosone. If the route succeeded, it should translate well to a successful total synthesis, as the only functionality missing from his model system compared to the natural product was the C7-prenyl group.

Scheme 33.

R. B. Grossman’s 2003 Approach Toward the Nemorosone Bicyclic Core.

Grossman’s synthesis commenced with Weiler alkylation46 of β-ketoester 139 and trapping of the dianion with prenyl bromide (140, Scheme 34). Cyclization to form cyclohexanone 141 was accomplished following Professor White’s47 optimized SnCl4 procedure. Lead(IV) acetate mediated alkynylation48 with tributylstannylated alkyne 142 proceeded favorably to afford acetal 143. Conversion of alkyne acetal 143 to silylated enal 144 was accomplished in three steps. Deprotection of the diethyl acetal was accomplished with formic acid. Disappointingly, at this stage all attempts to reduce the conjugated alkyne to a cis-enal failed. The Grossman group creatively solved this issue by resorting to a nice two step solution by forming the cobalt complex of the alkyne with Co2(CO)8 and then hydrosilylating the complex with triethylsilane in the presence of bis-trimethylsilyl acetylene (BTMSA).49 The stage was now set to test the key aldol cyclization step, which proceeded favorably in the presence of hydrochloric acid to afford bicyclic product 145 as a 1:1 mixture of alcohol diastereomers.

Scheme 34.

R. B. Grossman’s 2003 Synthetic Approach Toward Nemorosone.

Grossman’s route provides access to 145 from commercially available starting materials in only seven steps. Apart from not having a functional handle to install the C7-prenyl group, 145 is appropriately functionalized to complete the installation of the rest of the natural product nemorosone framework. The highlights of Grossman’s synthesis include the use of a challenging alkynylation, hydrosilylation and aldol cyclization reactions.

7. Mehta’s Approaches to Garsubellin A, Guttiferone A and Hyperforin

Professor Goverdhan Mehta has pursued this class of molecules vigorously for the last few years. His first approach50 focused on testing the viability of Kende’s51 palladium mediated cyclization to build the bicyclic core of garsubellin A (2, Scheme 35). In his model studies Professor Mehta decided to utilize the chiral pool in the form of a readily available terpene starting material.

Scheme 35.

G. Mehta’s 2004 Approach Toward the Garsubellin A Bicyclic Core.

Mehta’s asymmetric route was initiated by following Chapius52 two step procedure to convert (−)-α-pinene (146) to aldehyde 147 (Scheme 36). Conversion of 147 to enone 148 was accomplished by first dihydroxylating the olefin with catalytic osmium tetroxide, followed by Wittig olefination of the aldehyde, periodate diol cleavage and finally condensation between the newly liberated aldehyde and methyl ketone. At this juncture, Professor Mehta chose to functionalize C1 by using a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement. Thus, Luche53 reduction of enone 148 set the stage for a Johnson54 ortho-ester Claisen rearrangement from allylic alcohol 149. Hydroxylation of the carbon that eventually will become the bridgehead ketone was accomplished via a classic iodolactonization sequence. Toward that end, hydrolysis of the ethyl ester with potassium hydroxide was followed by treatment of the resulting carboxylic acid with iodine in the presence of potassium iodide. This two step sequence afforded lactone 151.

Scheme 36.

G. Mehta’s 2004 Synthetic Approach Toward Garsubellin A (Part 1).

Advancement of lactone 151 to Mehta’s garsubellin A model system core 154 was accomplished in seven steps (Scheme 37). Tributyltin hydride reduction of the iodide was followed by low temperature DibalH reduction of the lactone, which prevented over reduction. The crude lactol was then subjected to Wittig olefination that afforded bis-prenylated cyclohexanol 152. Quaternization of C1 was done by first oxidizing the alcohol with pyridinum chlorochromate and steroselective allylation with sodium hydride and allyl bromide (153). Silyl enol ether formation of the ketone finally allowed Mehta and his team to put their Kende cyclization approach to the test. To their delight, the proposed cyclization proceeded to form the expected bicyclic product (154), albeit in modest yield.

Scheme 37.

G. Mehta’s 2004 Synthetic Approach Toward Garsubellin A (Part 2).

Mehta’s approach successfully demonstrated the use of a palladium mediated 6-endo cyclization to construct the bicyclic core. Unfortunately, seventeen steps were needed to advance the starting chiral terpene to 154. The length of this sequence and modest yields of the key cyclization step inspired Mehta and his team to design alternate synthetic routes. These developments are discussed in the following sections.

Two years later a new and very efficient synthetic approach was published by the Mehta lab and it utilized a C4-C5 aldol disconnection to build the bicyclic core (Scheme 38).55 Their new strategy took advantage of dimedone as a cheap starting material source that provided them with a carbonyl group and eight of the carbons needed for garsubellin A (2), including the desired gem-dimethyl group.

Scheme 38.

G. Mehta’s 2006 Approach Toward the Garsubellin A Bicyclic Core.

Mehta’s second approach (Scheme 39) addressed the inefficiency of their first. Sequential Michael addition and prenylation of 131 with methyl acrylate and prenyl bromide afforded symmetrical 1,3-dione 155. Desymmetrization was accomplished in two steps by first hydrolyzing the methyl ester and then forming in situ a mixed anhydride with the newly formed carboxylic acid. The activated acid was then captured by one of the two enols to form 157. Lactone 157 was prenylated employing lithium bis-trimethylsilylamide as base. Structural NMR analysis indicated that alkylation had placed the new prenyl group anti to the existing one. The bicyclic core was at this stage beautifully assembled by subjecting the alkylated product to DibalH. The reductant first reduced the more reactive ketone and then reduced the lactone to a lactol, which opened up to unravel an enolate and a free aldehyde that now could react to form the C4-C5 bond of the bicyclic core (157). The product (157) contains the gem-dimethyl groups, C1 and C3 prenyl groups as well as useful oxidation states for further elaboration of the core. To complete installation of the C4-ketone Mehta elected to acylate both hydroxyl groups, selectively hydrolyze the C4-acetate and oxidize the resulting hydroxyl group (159).

Scheme 39.

G. Mehta’s 2006 Synthetic Approach Toward Garsubellin A.

This beautiful new route by the Mehta group assembles the core (157) in only six steps from dimedone, which compares very favorably with their seventeen step route to a core of similar complexity (Scheme 37). Apart from the missing C5-isopropyl acyl and C7-prenyl groups, the core has the needed functionality to advance toward garsubellin A (2). In addition to a well matched starting material (dimedone) for the task, the highlights of this route are the desymmetrization and the in situ reduction/aldol cyclization steps.

Inspired by the success of his new aldol approach Mehta and his team set out to further explore its potential. They decided to tackle a slightly more challenging natural product, guttiferone A (160, Scheme 40).56 Unlike garsubellin A (2), which contains a gem-dimethyl group at C6, guttiferone A (160) is decorated with an additional stereocenter at C6, resembling hyperforin (1). Furthermore, guttiferone A is also unique for having a prenyl group at C7 that is endo instead of the exo configuration found in other members of this family. One of the key questions they set out to address was if in the key aldol cyclization step, the C6/C7 relative stereochemistry would result in the desired anti-arrangement between the prenyl and homo-prenyl group.

Scheme 40.

G. Mehta’s 2008 Approach Toward the Guttiferone A Bicyclic Core.

As with his other two approaches, Professor Mehta chose again to take advantage of natural product starting materials for his guttiferone A (160, Scheme 41) route. Thus citral (161) was advanced in two steps to methyl ketone 162. A tandem Michael addition/Claisen condensation was accomplished by treating 162 with diethyl malonate and sodium ethoxide. The resulting cyclohexane β-ketoester was then decarboxylated to symmetrical diketone 163 following standard protocols. Ester formation and prenylation afforded a 1:1.2 mixture of diastereomers, with the desired product (164) as the minor isomer. Hydrolysis was followed by consecutive alkylations of the 1,3-dione first with 3-bromoethyl propionate and then prenyl bromide to afford 165. Ethyl ester hydrolysis set the stage to form lactone 166. Mehta and his team were delighted to learn that when this new product was subjected to DibalH the expected reduction/aldol cyclization cascade afforded the bicyclic core in 41% yield. Oxidation of the diol afforded trione 167. NMR and X-ray analysis unambiguously confirmed that the C6 and C7 stereocenters had the desired anti relationship.

Scheme 41.

G. Mehta’s 2008 Synthetic Approach Toward Guttiferone A.

This nice thirteen step sequence toward the guttiferone A core from citral demonstrates how Mehta’s initial route (Scheme 39) can be adapted to tackle other members of this family of natural products. The highlights of this new approach include an efficient synthesis of the 1,3-dione starting material and the key reduction/aldol anionic cascade.

Professor Mehta chose to also tackle hyperforin (1) using the same successful C4-C5 core building aldol cyclization strategy (Scheme 42).57 His model system was focused on a substrate core containing prenyl groups at C1, C3 and C6 along with the necessary oxygen handles for further functionalization. If successful, the absence of the key C7-prenyl group would need to be addressed by using an alternate starting material.

Scheme 42.

G. Mehta’s 2008 Approach Toward the Hyperforin Bicyclic Core.

Mehta’s approach toward the hyperforin core starts by double alkylation of 163 (Scheme 43). As before, ester hydrolysis followed by a thermal dehydrative desymmetrization performed in the presence of sodium acetate and acetic anhydride reliably delivers lactone 169. Selective alkylation of the less hindered face of the lactone enolate affords 170 containing the newly installed prenyl group in a trans-relationship with the bridgehead prenyl group. Gratifyingly, lactone 170 could be selectively reduced in the presence of diisobutylaluminum hydride and the resulting in situ generated enolate captured the newly formed aldehyde to form the desired bicyclic core of hyperforin (171).

Scheme 43.

G. Mehta’s 2008 Synthetic Approach Toward Hyperforin.

These results are not entirely surprising given the insights gained from the efforts detailed in Scheme 41. The only difference between the key pre-cyclization substrates 166 and 170 is the placement of the last prenyl group and the stereochemical relationship between the bridgehead prenyl group and the quaternary center homo-prenyl group. This second application of Mehta’s new synthetic approach clearly highlights its versatility and strengths.

Following this success, Mehta and his colleagues decided to make modifications to their route that incorporated the key C-7 prenyl group of hyperforin which would allow them to complete the total synthesis (Scheme 44).58 Furthermore, they were eager to advance a substrate void of the unnecessary C8-hydroxy group found in their previous two routes.

Scheme 44.

G. Mehta’s 2009 Approach Toward the Hyperforin Bicyclic Core.

Mehta again takes advantage of common intermediate 163 (Scheme 45). Similarly to his guttiferone approach (Scheme 41) he forms the vinylogous ester, which he then alkylates with prenyl bromide. As before, very poor diastereoselectivity is obtained in this reaction (1:1.2), with the minor diasteromer being the desired ester 172. He then takes advantage of the Stork-Danheiser strategy for forming enones (173). Selective reduction of the conjugated double bond was accomplished using nickel borohydride (174).59 Double alkylation of the ketone proceeded agreeably as did formation of enol lactone 176. Mehta’s cascade delivered yet again, and subsequent oxidation and alkylation afforded hyperforin core 177.

Scheme 45.

G. Mehta’s 2009 Synthetic Approach Toward Hyperforin.

Diketone 177, obtained in only sixteen steps from commercially available neral, represents Mehta’s most advanced intermediate to date. With all the prenyl groups in place the two challenges that Mehta and his team needed to address to complete the total synthesis of hyperforin were installation of the isopropyl acyl moiety and oxidation of C2.

In tackling the installation of the C1-C3 vinylogous acid moiety Mehta and his team decided to revisit the powerful Effenberger cyclization reaction first applied by Stoltz and coworkers toward garsubellin A (Scheme 46).60 Mehta envisioned matching this excellent reaction with one of their advanced hyperforin intermediates. If successful, this solution would streamline their synthesis in addition to solving the challenging C1-C3 oxidation problem.

Scheme 46.

G. Mehta’s 2010 Approach Toward the Hyperforin Bicyclic Core.

Mehta was able to quickly evaluate the performance of the Effenberger cyclization for the types of substrates needed to access hyperforin (Scheme 47). Toward that end ketone 174, from their previous route, was capped as silyl enol ether (178) and then treated with malonyl chloride in the presence of potassium hydroxide. Although successful, the Effenberger reaction yielded only modest amounts of trione 179. Methylation of the acid produced a poor mixture of esters, which could be equilibrated to 180 by treatment with trimethylorthoformate and acid. Bridgehead alkylation of C1 was accomplished using lithium diisopropylamide and trapping the resulting anion with prenyl bromide.

Scheme 47.

G. Mehta’s 2010 Synthetic Approach Toward Hyperforin.

Mehta’s Effenberger cyclization attempt confirms the challenges encountered in Stoltz’s earlier explorations in trying to optimize this reaction. With only the C3-prenyl and C5-isopropyl acyl groups lacking, advanced intermediate 181 looks like a good contender for accessing hyperforin.

8. Takagi’s Approach to Plukenetione A

Professor Takagi and coworkers made their initial bicyclic core disconnection strategies public in 2004.61 Their goal was to use a tandem double-Michael reaction sequence to construct the C1-C8 and C5-C6 bonds of the [3.3.1] bicyclic core. Although their proposal was proven feasible, the yields for the tandem reaction were dismal. They then turned their attention on optimizing the C1-C8 intramolecular Michael reaction (Scheme 48) with respect to cyclization efficiency and stereochemical control.62 The fruits of their labor were then applied toward the synthesis of a novel tricyclic adamantane type member of the phloroglucinol family, plukenetione A (182).63

Scheme 48.

R. Takagi’s 2008 Approach Toward the Plukenetione A Bicyclic Core.

Starting with dihydroresorcinol (5, Scheme 49), Takagi employed Heathcock’s methylation method42 to access vinylogous ester 183. Deprotonation of 183 with lithium diisopropylamide and trapping with methyl iodide afforded known vinylogous ester 184.64 Michael reaction between the enolate obtained from 184 and acrylate 185 proceeded favorably to form 186 primarily as a single acrylate isomer (E-isomer shown). After some experimentation, Takagi and his team identified potassium carbonate in refluxing toluene in the presence of tetrabutylammonium bromide as their optimal conditions for the key bicyclic core forming Michael cyclization reaction (187). Gratifyingly, the cyclization had also secured the desired trans relationship between the C7 and C8 substituents. Reduction of the bridgehead ketone and addition of methyl cerium to the ethyl ester yielded 188. The challenging C4 allylic oxidation was accomplished using Corey’s palladium mediated procedure.65 This key step was followed by a chromium oxidation and temporary protection of the tertiary alcohol as a trimethylsilyl ether (189). The C3 benzoylation was successfully accomplished employing LTMP as a base (190), and during the workup of this reaction the silyl ether conveniently fell off. With the tricarbonyl group in place and the tertiary alcohol free, Takagi could focus his attention on the forming the adamantane core. Formation of 191 was accomplished by treating 190 with stoichiometric amounts of triflic acid in refluxing dichloromethane.

Scheme 49.

R. Takagi’s 2008 Synthetic Approach Toward Plukenetione A.

Professor Takagi’s approach demonstrates a nice sequential Michael addition approach to the bicyclic core of Plukenetione A. His successful cromium-mediated allylic oxidation of 188 is noteworthy as others have struggled with such transformations for similar systems. The cationic capture with the C3-nucleophile is an efficient way to complete the tricyclic core of the natural product.

9. Barriault’s Approach to Hyperforin

Professor Louis Barriault of the University of Ottawa has over the years designed numerous clever reaction cascades to tackle challenging natural product scaffolds. Intrigued by the complex [3.3.1] cores of many of the phloroglucinol natural products as well as other notable [m.n.1] bicyclic natural products, he set out to devise novel reactions to assemble these cores (Scheme 50). His first approach involved transforming in one step a cis-indane core, strategically decorated with an exo olefin and an adjacent acetonide, to a [3.3.1] bicyclic product by treating it with a Lewis acid (SnCl4).66 This sequence involved cleavage of the acetonide followed by Prins cyclization of the resulting intermediate, which was then poised for a pinacol cyclization to form the C4-C5 bond. More recently, Barriault has demonstrated that the C1-C8 bond of hyperforin can be formed via a novel gold catalyzed cyclization union between a silyl enol ether and an alkyne.67

Scheme 50.

L. Barriault’s 2005 and 2009 Approaches Toward the Hyperforin Bicyclic Core.

Barriault’s new gold catalyzed cyclization approach commenced by converting allyl ketone 192 (Scheme 51) to β-keto ester 193. Propargylation was accomplished using cesium carbonate in acetone (194). Conversion of ketone 194 to silyl enol ether 195 set the stage to test the feasibility of his cyclization approach. Gratifyingly, treatment of 195 with catalytic amounts of cationic gold catalyst 196 in acetone resulted in the formation of bicyclic product 197 in 87% isolated yield.

Scheme 51.

L. Barriault’s 2009 Synthetic Approach Toward Hyperforin.

One of the main strengths of Barriault’s novel 6-endo gold cyclization strategy is that it allows formation of the bicyclic core with bridgehead substituents at both C1 and C5. No reports have emerged as of yet detailing further adaptation of this approach to one of the phloroglucinol natural product targets.

10. Danishefsky’s Approaches to Garsubellin A, Clusianone and Nemorosone

Professor Danishefsky has been an active contributor in this area of research as well and his efforts to date have resulted in three completed total syntheses. He first set his sights on garsubellin A (2, Scheme 52).68 Following a close structural analysis of its unique core he proposed that the bridged bicyclic core could be assembled by forming the C5-C6 bond using an iodocarbocyclization. If successful, this approach would allow Danishefsky and his coworkers to start with a readily accessible prenylated cyclohexanedione precursor.

Scheme 52.

S. J. Danishefsky’s 2006 Approach Toward Garsubellin A.

Starting with silyl protected phloroglucinol derivative 198 (Scheme 53), Danishefsky and Siegel selectively prenylated the aromatic core para from the bulky silyl group. Following a predictable dihydroxylation, protection, deprotection sequence (199→201), the stage was set for a key dearomatization event. This para-specific functionalization task was accomplished employing a palladium catalyst in the presence of allyl methyl carbonate (202). An equally impressive step followed, where upon treatment with perchloric acid in one pot a high yielding deprotection, cyclization, dehydration sequence unfolded to form 203. Grubbs cross metathesis similar to that employed by Stoltz was followed by an iodocarbocyclization reaction (205) closely related to the selenocyclization approach chosen by Nicolaou. Iodination at C3 was accomplished using iodine in the presence of CAN. Interestingly, Mg-I exchange at the bridgehead occurred at a lower temperature than the desired C3 metal-halogen exchange, resulting in an unexpected transannular Wurtz coupling followed by the desired allylation. This unwanted outcome was easily remedied by opening the unwanted cyclopropane (206) with TMSI to form iodinated bicyclic core which was then subjected to a Keck allylation.69 A double cross metathesis reaction proceeded favorably to form garsubellin A lacking only the C5-acyl group (208). Bridgehead iodination was followed by Knochel’s magnesium iodine exchange protocol70 and trapping with isobutyraldehyde (209). This critical sequence could only be accomplished if the tertiary hydroxyl group was first temporarily protecting as a silyl ether. Danishefsky’s total synthesis of garsubellin A was completed by oxidizing 209 with Dess-Martin periodinane and deprotecting the tertiary silyl group.

Scheme 53.

S. J. Danishefsky’s 2006 Total Synthesis of Garsubellin A.

Danishefsky’s total synthesis of garsubellin is not only concise, 17 steps, but is notable for its choice of starting material and creative assembly of reactions. The most notable transformations in his route are the dearomatization, iodination and cross-coupling reactions. Iodine plays a particularly prominent role in his synthesis, being used as the enabling element for forming the carbocyclic ring, installing C3-prenyl, C5-isobutyryl and C7-prenyl groups as well as alleviating an unwanted cyclopropanation reaction. Interestingly, it is worth noting that when added together around 1/3 of the steps in Danishefsky’s synthesis involve the iodine atom in some form.

Following his success in expediently building garsubellin A, Professor Danishefsky turned his attention to other members of this natural product family. He argued that his route could be appropriately modified to provide access to two other biologically significant members, nemorosone (3) and clusianone (4) (Scheme 54).71 He proposed that iodocarbocyclization could again serve as the bicyclic core forming step and that the route could be diverged from that point to form either nemorosone (3) or clusianone (4).

Scheme 54.

S. J. Danishefsky’s 2007 Approach Toward Nemorosone and Clusianone.

Danishefsky’s nemorosone route commenced with a palladium mediated double allylation of 210 (Scheme 55), which afforded symmetrical enoate 211. Cross metathesis was then followed by deprotection of one of the vinylogous esters, thereby setting the stage for the key iodocarbocyclization reaction, which had proceeded favorably in their garsubellin synthesis. Interestingly, this subtle structural change greatly impacted the outcome of the reaction and more than half of the material was funneled into undesired O-alkyl cyclization pathways. Following extensive optimization studies, 32% yield of 214 was the best that could be accomplished. Deiodination and cyclopropyl ring opening was followed by a Keck allylation (215). At this point bridgehead iodination (216) led the way for incorporating the C5-acyl group (217) following the garsubellin A precedence. Introduction of the C3-prenyl group differed from above and utilized C3-lithiation, transmetallation with a cuprate and trapping with allyl bromide to decorate C3 in high yield with an allyl group. Cross metathesis of the C3- and C7-allyl groups transformed them into their prenyl forms (218). Total synthesis of nemorosone (3) was completed by thermal deprotection of the methyl ester with the help of lithium iodide and 2,4,6-collidine. By adapting his garsubellin A approach, Danishefsky managed to deliver nemorosone in only 14 linear steps from commercially available aromatic building blocks.

Scheme 55.

S. J. Danishefsky’s 2007 Total Synthesis of Nemorosone.

The flexibility of Danishefsky’s nemorosone route was further demonstrated by advancing a late stage intermediate (215, Scheme 56) to clusianone (4). Nemorosone and clusianone are isomeric and only differ in whether C3 and C5 are decorated with a benzoyl or a prenyl group. After analyzing the best sequences for introducing C3 and C5, Danishefsky chose to first install the C3 benzoyl group using a direct lithiation approach, trapping with benzaldehyde and oxidizing the resulting carbinol to trione 219. Bridgehead lithiation proceeded as before to form 220. Keck allylation using triethylborane as a radical initiator installed the bridgehead allyl group in high yield (221). The total synthesis of clusianone was accomplished following a double cross metathesis reaction and hydrolysis of the vinylogous methyl ester. With his thirteen step total synthesis of clusianone Danishefsky managed to further improve upon the efficiency of his concise benchmark syntheses of garsubellin A (17 steps) and nemorosone (14 steps).

Scheme 56.

S. J. Danishefsky’s 2007 Total Synthesis of Clusianone.

Danishefsky’s concise total syntheses of nemorosone and clusianone serve as a testament to the value and flexibility of the synthetic blueprint he designed and executed for garsubellin A.

11. Simpkins’ Approaches to Clusianone, Garsubellin A and Nemorosone

Professor Simpkins from the University of Nottingham has been a key player in this area of research, having completed total syntheses of three members of the bridged bicyclic phloroglucinol family to date as well as making methodological contributions that have greatly impacted the field. In his first report in 2006 he presented a new concise route to clusianone (4, Scheme 57).72 Although the bicyclic core was assembled using the Effenberger cyclization, following the example of Stoltz7 a few years earlier, it was how he proceeded from that point onward, using well matched anion chemistry, that caught the attention of the synthetic community.

Scheme 57.

N. S. Simpkins’ 2006 Approach Toward Clusianone.

Starting by assembling known ester 22273 (Scheme 58), Professor Simpkins then followed the Stork-Danheiser protocol to incorporate an additional prenyl group (223). Conjugate addition and enol ether formation afforded a mixture of isomeric methyl enol ethers (224). Effenberger cyclization proceeded favorably and the resulting bicyclic product was then esterified using trimethylorthoformate in the presence of acid (225). Up until this point, Professor Simpkins’ route had followed a classic path. He then went on to demonstrate that ester 225 could be advanced in only three steps to clusianone (4). This he accomplished by performing a high yielding bridgehead alkylation at C1, followed by direct lithiation of C3 and trapping with benzoyl chloride to afford 227. From an efficiency perspective it simply does not get better than this, to be able to incorporate both C1 and C3 substituents in their fully native form in a controlled fashion onto a complex natural product framework. Simple vinylogous ester hydrolysis then afforded clusianone in only thirteen linear steps from 5.

Scheme 58.

N. S. Simpkins’ 2006 Total Synthesis of Clusianone.

To further highlight the usefulness of his bridgehead alkylation approach, Professor Simpkins demonstrated a year later that an advanced synthetic intermediate (225, Scheme 59) could be kinetically resolved using a chiral lithium base.74 Employing two equivalents of the bis-lithiated form of Koga’s base,75 one enantiomer of racemic 225 is preferentially alkylated with prenyl bromide in the presence of a chiral base leaving behind enantioenriched (+)-228, which is recovered in 25% isolated yield and 98% ee.. Advancement of (+)-clusianone was then accomplished following his three step alkylation, hydrolysis sequence.

Scheme 59.

N. S. Simpkins’ 2007 Total Synthesis of (+)-Clusianone.

Impressively, Simpkins’ short route to clusianone does not use a single oxidation or reduction step. The conciseness of this route stems from coupling the powerful Effenberger reaction with C3- and C5-alkylation reactions that directly introduce the desired C3-prenyl and C5-benzoyl groups. Although the Effenberger cyclization is low yielding, the reaction generates a significant amount of molecular complexity. The highlight of Simpkins sequence is the direct bridgehead lithiation/alkylation reaction. This powerful step allows advancement of simpler bicyclic constructs.

Having successfully synthesized clusianone, Professor Simpkins turned his attention to garsubellin A, pursuing two different approaches. One approach follows a similar path to his previous synthesis (Schemes 62 and 63) and the other utilizes a rapid asymmetric entry point to the bicyclic trione core from a simple and readily available natural product (Scheme 60). For his alternate approach, the bicyclic core is formed by a 1,6-Michael addition between a 1,3-dione and an in situ generated para-quinone methide (Scheme 60).76

Scheme 62.

N. S. Simpkins’ 2007 Second Approach Toward Garsubellin A.

Scheme 63.

N. S. Simpkins’ 2007 Formal Total Synthesis of Garsubellin A.

Scheme 60.

N. S. Simpkins’ 2007 First Approach Toward Garsubellin A.

Troubled by the low yield of the Effenberger cyclization and the fact that it affords a racemic bicyclic core, the Simpkins group wondered if their powerful late stage alkylation approach could be coupled with a more useful alternate asymmetric synthesis of the chiral trione bicyclic core (Scheme 61). Digging through the literature they came across a remarkable transformation described by Sears77 which converts (+)-catechin to trione 231 in a single step. This transformation, which starts with a readily available natural flavanoid, proceeds in excellent yield and involves the base mediated ring opening of the benzopyran core thus generating a para-quinone that can be captured in a 1,6-intramolecular Michael addition fashion with the newly released phenoxy core. In a single step, an asymmetric core is accessed and although stripped of much functionality, the Simpkins group envisioned using their alkylation strategy to install the C1, C3 and C5 appendages. While the hydroxy handle at C7 would serve well for introducing the prenyl group, the main obvious drawback to this approach would be a non-trivial late stage conversion of the oxygenated aromatic C6 functionality into a gem-dimethyl.

Scheme 61.

N. S. Simpkins’ 2007 Synthetic Approach Toward Garsubellin A.

Esterification of the product from the base cascade (231) process proceeded well. At this stage the Simpkins group decided to protect both the C7-hydroxyl functionality and the bridgehead ketone. This was accomplished by silylating the hydroxy group and converting the ketone to a dimethyl acetal (233). Gratifyingly, their bridgehead alkylation reaction helped install the C1-prenyl group, and instead of pursuing the installation of the C3- and C5-alkyl sidechains the Simpkins group chose to complete the synthesis of the C1-garsubellin A tetrahydrofuran moiety. This oxygenation sequence would mask the prenyl group and therefore cause fewer complications moving further. A nice two step solution was developed that involved dimethyldioxirane epoxidation of the prenyl sidechain and a trimethylsilyl chloride mediated 5-exo-tet oxirane ring opening. Although this sequence was high yielding, the desired diastereomer (235) was the minor product.