Abstract

Longstanding immunological dogma holds that flexible immune recognition, which forms the mechanistic basis of adaptive immunity, is strictly confined to the lymphocyte lineage. In higher vertebrates, flexible immune recognition is represented by recombinatorial antigen receptors of enormous diversity known as immunoglobulins, expressed by B lymphocytes, and the T cell receptor (TCR), expressed by T lymphocytes. The recent discovery of recombinatorial immune receptors that are structurally based on the TCR (referred to as TCR-like immunoreceptors, “TCRL”) in myeloid phagocytes such as neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages now challenges the lymphocentric paradigm of flexible immunity. Here, we introduce the emerging concept of “extralymphocytic flexible immune recognition” and discuss its implications for inflammation and aging.

Keywords: TCR, macrophage, neutrophil, immunosenescence

The lymphocentric paradigm of adaptive immunity

Vertebrate host defense is commonly subdivided into two arms – innate immunity and adaptive immunity [1]. Historically, this concept has its origin in Elie Metchnikoff’s discovery of phagocytosis, i.e. the ability of cells to ingest solid particles, as a basic principle of innate host defense in 1883 [2] and the identification of antibodies by Behring and Kitasato seven years later as the defining component of adaptive immunity [3]. Two major populations of professional phagocytes, neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages, are the founding pillars of the innate immune response and, as such, constitute the first line of host defense against infections [4,5]. It is widely accepted that these ancient immune cells initiate inflammatory responses, phagocytose and kill pathogens, recruit natural killer cells (NK), and engage dendritic cells that in return trigger the adaptive immune response.

Longstanding immunological dogma holds that the molecular machinery of adaptive immune recognition in higher vertebrates, which is represented by immunoglobulins and the T cell receptor (TCR), is restricted to effector cells of the lymphocyte lineage [1,6]. This lymphocentric concept of variable immunity is based on Fagraeus’ groundbreaking observation in 1947 that plasma cells are the cellular source of immunoglobulins [7]. The identification of the hypothesized, yet long-elusive, second variable immune receptor in T lymphocytes in the mid 1980s [8] has corroborated the concept that TCR expression in vertebrates is a prerequisite of the T lymphoid lineage (hence designated “T cell receptor”). In hindsight, however, the general acceptance of this concept contrasts strikingly with the complete absence of reports from the literature that provide explicit or systematic experimental proof that immune cells beyond the T cell lineage are indeed incapable of expressing recombinatorial T cell receptors.

Recombinatorial TCR-like receptors (TCRL)

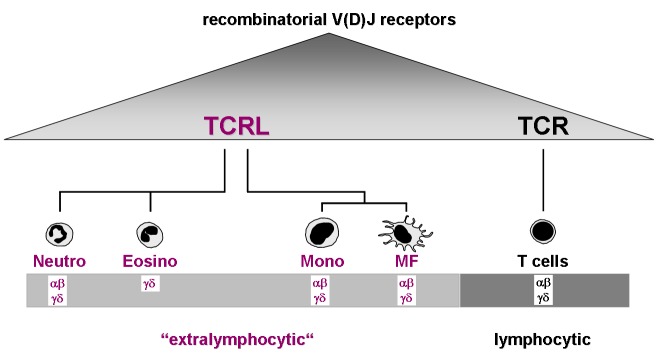

Recent studies in myeloid phagocytes now challenge the lymphocentric paradigm of adaptive immunity (Fig. 1). The initial observation came from work performed in our laboratories which demonstrated that peripheral blood neutrophils from healthy humans and mice possess rearranged T cell receptors [9,10]. A 5–8% fraction of neutrophils was identified in the circulation that constitutively expresses variable immune receptors that are composed of the TCR α- and β-chain. These TCR-based immunoreceptors (TCR-like immune receptors, “TCRL”) are expressed across the entire human life-span [11]. Circulating human neutrophils were also shown to constitutively express the TCR γ- and δ-ligand binding subunits and all critical components of the TCR signaling complex [9]. These unexpected findings provided evidence, for the first time, that neutrophil granulocytes express a flexible antigen recognition machinery that is homologous to that present in T cells. The presence of TCRL in the granulocyte lineage was confirmed by a subsequent study which demonstrated expression of a functional TCRγδ in circulating eosinophil granulocytes from healthy individuals [12].

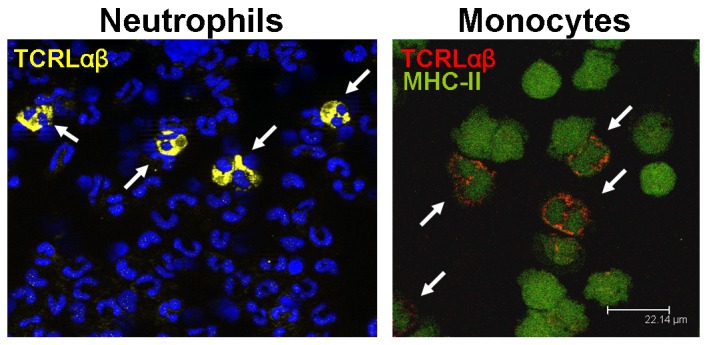

Figure 1.

Circulating human neutrophils and monocytes express αβT cell receptor-like recombinatorial immune receptors (TCRLαβ). The confocal fluorescence immunocytochemistry images show ∼5–8% subpopulations of circulating neutrophils (left) and monocytes (right) that express the TCRLαβ (arrows). TCRLαβ positive neutrophils and monocytes display yellow and red fluorescence, respectively. Nuclei are counterstained in the left image (blue). CD15+ and CD14+ purified peripheral blood neutrophils and monocytes, respectively, were isolated from representative healthy donors and immunostained using antibodies against the TCRαβ (yellow, neutrophils; red; monocytes). Monoytes were costained for MHC-II (green). Adapted from Puellmann et al. [9] and Beham et al. [13].

Consistent with the identification of TCRL expressing granulocytes, a most recent study provides compelling evidence that subpopulations of peripheral blood monocytes, which next to neutrophils constitute the second professional phagocyte population in the circulation, also possess TCRαβ-based combinatorial receptors [13]. These TCR-like receptors were also identified in monocyte-derived macrophages that had been differentiated under in vitro conditions and resident macrophages from tissue of healthy donors indicating that both monocytic phenotypes are capable of expressing TCRL.

TCRLαβ immunoprofiling in peripheral blood neutrophils and monocytes from healthy individuals reveals expression of diverse and individual-specific TCRLαβ repertoires. This indicates that TCRL represent a flexible immune receptor system [9,13]. Consistent with this, rearrangement analyses of expressed TCRαβ variants in neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages and eosinophils have routinely shown V(D)J recombination of the TCR α/β loci and TCR γ/δ loci, respectively, in these myeloid cells. Furthermore, GM-CSF stem cell progenitor experiments established that rearrangement of the TCRL Vβ locus is an early event during myeloid lineage development [9,12,13].

Infection of macrophages with the bacterial pathogen mycobacterium BCG induces changes of the expressed TCRLαβ repertoires and leads to a significant induction of the macrophage-TCRL [13]. TCRL repertoires are also dynamically regulated in response to non-infectious exogenous stimuli. For example, in vivo G-CSF administration leads to transient suppression of TCRL repertoire diversity in human neutrophils and exposure of cultivated macrophages to IL-4 or IFNγ induces distinct repertoires changes in vitro [9,13]. Taken together, these findings clearly demonstrate that TCRL meet two cardinal criteria of adaptive immune systems - repertoire flexibility and responsiveness to exogenous stimuli.

Hidden in the shadow of T cells

Given that the existence of the TCR has already been hypothesized and proven in the early 1970s and 1980s [14,8], respectively, the question inevitably arises why the discovery of the TCRL in myeloid immune cells did not occur sooner. In all likelyhood, it was an unfavorable constellation of conceptual and technical hindrances that may have obivated earlier detection of TCR-based receptors outside the T lymphocyte lineage. The first major obstacle was the absence of a theoretical concept of non-lymphoid TCR expression. Long before its molecular identification the postulated TCR was believed to be the prototypic feature of T cells and thus by definition absent from the other branch of recombinatorial immunity represented by B cells. This explains why in all the initial TCR cloning studies a specific effort was made to exclude that the identified TCR chains were not of B cell origin and no systematic investigation of TCR expression in other tissues was conducted [15–23]. Besides this conceptual bias, a series of technical shortcomings and methodological intricacies contributed to prevent earlier identification of TCRL. These include the non-availability of reverse transcription PCR until 1988 [24] which allows for highly sensitive detection of gene expression and the fact that fluorescence-based flow cytometry routinely fails to unequivocally identify TCR bearing leukocyte populations outside lymphocytes [25]. Moreover, gene ablation studies in mice in which integral components of the TCR machinery had been deleted (e.g. rag1/rag2 knockouts, TCRαβ/γδ null mice) also did not give overt clues for the existence of TCRL. Most likely this is owing to the fact that TCR ablation massively compromises the development and function of T cells [26–32], a dominant biological effect that may have largely masked phenotypic alterations associated with defective TCRL in neutrophils and macrophages. At the turn of the millenium, the advent of large-scale gene expression microarrays another quantum leap technology became available to researchers that may have potentially facilitated identification of TCR expression in myeloid cells. Of note, several microarray-based expression profiling studies have indeed documented gene expression of integral components of the TCR ligand binding and signaling complex in neutrophils and macrophages [33–39]. In retrospect, it is puzzling, however, that this trail of clues for the existence of TCR-based recognition molecules beyond T cells has been completely ignored.

Potential functions of TCRL

Due to the recentness of the identification of combinatorial TCRL in phagocytes only little is currently known on what cellular function they serve in host defense. The finding that canonical CD3/CD28 costimulation of the neutrophil-TCRL induces the release of the major neutrophil chemoattractant CXCL8 (IL-8) suggests roles for the TCRL in neutrophil self-recruitment [9]. Consistent with this, CD3 mediated engagement of the macrophage-TCRL results in selective secretion of the monocyte chemoattractant CCL2 (MCP-1) by macrophages [13]. Similarly as in T cells, activation of TCR-based receptors appears to exert antiapoptotic functions. This is evidenced by the demonstration that CD3/CD28 costimulation of human neutrophils leads to upregulation of the antiapoptotic protein bcl-xL and promotes neutrophil survival [9]. It is therefore likely that activation of the TCRL prolongs the functional life span of neutrophils at sites of inflammation. Considering that TCRL are expressed by cells that function as professional phagocytes, the obvious question is whether these recognition proteins interfere with the process of phagocytosis. Indeed, bait targeting experiments in human proinflammatory M1 macrophages demonstrate that TCRL facilitate phagocytosis [13]. Of note, the observed positive effect on phagocytosis was in the same order of magnitude as that mediated by the potent mediator of phagocytosis complement receptor 3 (CR3). Further support for the implication of the TCRL in phagocytosis comes from experiments in rag1 knockout mice which demonstrate that macrophages deficient in functional TCRL have reduced phagocytosis capacity [13]. Together, available evidence suggests potential roles of the TCRL as a modulator of cell survival, self-recruitment and phagocytosis. More evidence, however, is required to assess whether this also holds true when TCRL are activated by specific agonists in vivo.

TCRL extend the basis of variable immunity

Current evidence indicates the presence of TCRLαβ or TCRLγδ in four populations of myeloid immune effector cells: neutrophils, eosinophils, monocytes and macrophages. The identification of flexible recognition molecules in these professional phagocytes has two fundamental implications for our understanding of the workings of innate and acquired immunity. First, the demonstration of immune receptors beyond the realm of lymphocytes reveals that variable immune recognition in higher vertebrates is built on a broader cellular foundation than commonly thought. This gives formal proof for the existence of a molecular platform for extralymphocytic flexible immune recognition (Fig. 2). Moreover, it predicts adaptive immune mechanisms in vertebrates outside T cells that rely on the TCRL (“extralymphocytic adaptive immunity”) [25].

Figure 2.

TCRL expression in phagocytes. The V(D)J recombined TCRL variable chains (α-δ) that have thus far been identified in each phagocyte population are indicated. The existence of TCRL extends the cellular basis for flexible immune recognition in jawed vertebrates beyond T cells and provides a molecular platform for extralymphocytic flexible immune recognition. This diagram was adopted from a previous publication [25].

The second major implication of the existence of TCRL is that it demonstrates, for the first time, the coexistence of phagocytosis and flexible immune recognition in mammalian immune cells. Both fundamental principles have been previously thought to be mutually exclusive cellular functions. Their presence in phagocytes thus unifies the imunological armamentarium of myeloid cells with that of lymhpoid cells. It has been proposed that TCRL expressing phagocytes may represent a host defense system that is positioned between the innate and the adaptive branch of immunity which may bridge both arms of the immune system [40,41,25]. From a teleological viewpoint, a fast-acting phagocytic and at the same time flexible immunological intervention system would certainly make sense, because it fills the conceptual gap between first-line invariant host defense and the T cell based flexible immune response which occurs with a considerable temporal delay [1].

Immunosenescence of neutrophils and macrophages

A large body of evidence as accumulated in the past decade to suggest that aging has a profound impact on the phenotype and function of various immune cells [43,44]. Neutrophils and macrophages play a key role in the innate immune system in that they constitute the first line of defense against tissue damage and invading pathogens [4,5]. Immunosenescence, that is the decline of diverse immune functions at old age, has been well established for neutrophils [43,45]. For example, neutrophils from old individuals have reduced phagocytic capacity, generation of reactive oxygen species, intracellular killing and degranulation [46]. In contrast, several studies have established that neutrophil counts in the blood are not lowered in the elderly [47,48].

Similar to neutrophils and T cells, functional changes have also been reported for monocytes and macrophages from aged humans, rats and mice [49–53]. endocytic These include the phagocytic ability, the capacity to release chemokines and the function of invariant immune recognition receptors. However, there is little information as to whether structural components of the phagosome or receptors, which are implicated in the phagocytic process, undergo changes during aging.

Impaired function of immune recognition receptors in aged macrophages has been evidenced for toll-like pattern recognition receptors (TLR) [54,55]. For example, alveolar macrophages from aged rats show a significant decrease in the production of reactive oxygen species in response to the TLR4 ligand LPS [55]. On the other hand, bone marrow macrophages from aged mice have increased susceptibility to oxidants and an accumulation of intracellular reactive oxygen species which is paralleled by telomere shortening [56]. Expression of TLR 1–9 genes is reduced in splenic macrophages and in peritoneal macrophages from old relative to young C57BL/6 mice [57]. Furthermore, evidence for the implication of the TCR immune recognition machinery has been reported for M1 polarized macrophages from aged mice which display decreased cell surface expression of the MHC class II IA complex [58]. Whether the observed age-associated dysfunction of macrophages is rather the result of their functional adaptation to age-related changes in tissue than a primary decline of physiological function [52] is an intriguing, yet unsolved question.

TCRL undergo immunosenescence

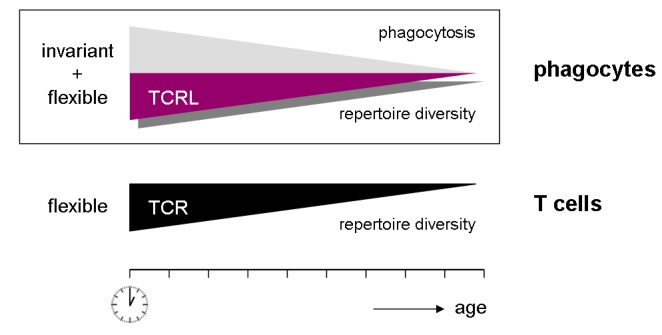

Recent work from our groups now demonstrates that TCRL are implicated in immunosenescence. We observed that peripheral blood neutrophils display a 3–4 fold reduction in neutrophil TCRL repertoire diversity of their TCRL Vβ repertoire diversity in >70 year old individuals relative to young adults. The decline of the neutrophil TCRL Vβ repertoires is characterized by a strikingly predominant usage of a few selected Vβ chains and a high degree of clonotype sharing in the elderly [11]. A similar contraction of TCR repertoire diversity has been reported in T cells at old age in humans and mice [59,60]. These findings strongly suggest that TCR-based immunoreceptors in neutrophils and T cells undergo a concurrent decline during aging (Fig. 3). However, the dramatic TCRL repertoire contraction observed in aged neutrophils appears to be less pronounced compared to that of the TCR in CD4+ T lymphocytes for which a >90% contraction of TCR repertoire diversity has been reported [61]. It is presently unknown whether the TCRL in monocytes/macrophages also undergoes age-related repertoire narrowing. By analogy, however, this appears likely, given that age-dependent repertoire contraction of the TCR-based immunoreceptors occurs both in neutrophils and T lymphocytes. Experiments are underway to address this important question.

Figure 3.

Conccurrent decline of the capacities for phagocytosis and flexible immune recognition in myeloid phagocytes during aging. The myeloid machinery for flexible immune recognition is based on the recently identified recombinatorial TCRL. This process is paralleled by the decline of the T cell receptor (TCR) in the lymphoid lineage.

At this point, it is unclear whether the decline in neutrophil TCRL repertoire diversity and the striking dominance of a limited number of TCRL Vβ clonotypes is linked to compromised recombination activity (“senescent recombination”) or dysregulated transcriptional dynamics of individual TCRL producing neutrophil clones. If one takes into account that the TCRL in neutrophils and macrophages may function as facilitators of phagocytosis, it is possible that the impaired phagocytic activity oberved in aged macrophages and neutrophils is not only the consequence of a compromised function of the structural components of the cellular phagocytosis machinery but also the result of reduced TCRL expression of.

It has been postulated that loss of organized complexity is a characteristic feature of aging and disease [62,63]. In light of this decomplexification theory, the decline of TCRL or TCR repertoire diversity in aged individuals can be viewed as the loss of functional plasticity of the highly complex neutrophil and T cell flexible immune systems. Consistent with this concept, the striking expression of only a few dominant TCRL Vβ clonotypes we noted in aged neutrophils may reflect the emergence of a dominant functional mode. Intriguingly, this phenomenon of decomplexification is often observed in non-linear regulatory systems following the breakdown of complex dynamics [64].

Implication in disease

The presence of flexible immune receptors in neutropils and macrophages offers a fascinating new angle on understanding their role in inflammation. Because neutrophils are routinely the first cells at the site of inflammation [4] and macrophages are ubiquitously present in tissues both phagocyte populations are implicated in a wide spectrum of clinical inflammatory diseases. It is thus foreseeable that the neutrophil and macrophage TCRL are involved in numerous clinical pathologies. In keeping with this, efforts to test for the implication of TCRL in inflammatory diseases have as yet consistently shown that TCRL bearing neutrophils and macrophages accumulate at sites of inflammation [13,65]. For example, a recent study in which we tested in detail the potential role of the macrophage-TCRL in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis revealed that the vast majority of the macrophages that accumulate in the inner host-pathogen contact zone of caseous granulomas from patients with lung tuberculosis express the TCRLαβ [13]. This intriguing finding strongly suggests that TCRLαβ bearing macrophages constitute the front line of cellular defense against mycobacteria. Consistent with this, in vitro infection of macrophages with M. bovis BCG induces formation of macrophage clusters that express restricted TCRL Vβ repertoires. More importantly, experimental tuberculosis in chimeric rag1−/ − mice, which were reconstituted with wild-type T cells, revealed that ablation of the macrophage-TCRL in the presence of intact T cells results in disorganized tuberculous granulomas [13]. Collectively, these experiments strongly suggest that the TCRL in macrophages is critcally involved in the formation of the tuberculous granuloma. Recent work also demonstrates that the neutrophil-TCRL is implicated in inflammatory disease. This is evidenced by the observations that a massive induction of the neutrophil-TCRL occurs in the circulation in autoimmune hemolytic anemia [65] and in the cerebrospinal fluid from patients with acute bacterial meningitis (Fuchs T et al., unpublished).

Based on these initial studies, work is underway to test whether TCRL are implicated in other inflammatory processes. Our attention has focused primarily on two promising candidate diseases – atherosclerosis and cancer – based on their eminent epidemiological importance and the fact that both entities represent paradigmatic diseases of advanced age. Whereas it is well established that macrophages are key players in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis [66], it was only recently that tumor infiltrating macrophages (commonly known as tumor associated macrophages, TAM) have gained considerable attention owing to evidence demonstrating a pivotal role for these cells in promoting angiogenesis and tumor progression [67–70]. In fact, recent ex situ TCRL clonotype analyses in our laboratories consistently reveal expression of TCRL by macrophages in advanced lesions of atherosclerosis and melanoma metastases (Fuchs T et al., unpublished). More work is necessary, however, to substantiate these fascinating preliminary results.

Perspectives

The discovery of TCR-based recombinatorial receptors in myeloid immune cells comes as a big surprise and without a pre-existing theoretical framework. It challenges the lymphocentric concept of flexible immune recognition and adds a new complexity of unknown dimension to our present understanding of the workings of the vertebrate immune system. The scenario bears somewhat of a resemblance to navigators who have landed on an unknown coast wondering about the size of the land behind it. Theoretically, it could be an island of limited size viz. a finding of limited physiologic importance. However, in light of the constellation that (i) neutrophils initiate virtually any form of inflammation, (ii) macrohages are strategically positioned throughout the entire body, (iii) TCRL have persisted in these evolutionarily ancient phagocytes throughout evolution and (iv) TCRL are implicated in major inflammatory syndromes, it is rather likely that a vast uncharted territory of immunology may lie ahead of us. This view is also supported by a growing body of evidence that points to the existence of host response mechanisms in innate immune cells which involve immunologic memory beyond lymphocytes (“innate memory”) [71]. With the underlying molecular components for innate memory not yet identified, it is thus tempting to speculate that TCRL form (in part) the mechanistic basis for these phenomena.

A major challenge in the quest to understand the biological significance of TCRL will be the assessment of their true TCRL repertoire diversity under physiological conditions and the elucidation of the dynamics of repertoire changes that are associated with age and disease. With the quantum leap technology of next generation sequencing a powerful tool has recently become available that will allow direct sequencing of entire TCRL transcriptomes [72–74]. Another important question is whether neutrophils, eosinophils and monocytes/macrophages represent the only leukocyte populations that rely on TCRL. It is possible that other cells of myeloid origin are capable of expressing TCRL recognition molecules. Promising candidates include tissue-specific macrophage populations such as Kupffer cells, osteoclasts and dendritic cells. It will be challenging to outline the actual cellular basis of TCRL in non-lymphoid immune cells.

Although our knowledge of the immunological relevance of TCRL is still fairly rudimentary, available evidence links these novel immune receptors to both aging and inflammatory disease. It will thus be rewarding to explore the potential roles of TCRL in age-associated diseases. In particular, atherosclerosis as the paradigmatic inflammatory disease of advanced age will be a most attractive target for investigating the pathophysiological role of TCRL in macrophages. Other diseases in which macrophages play a key pathophysiogical role include bone osteoporosis [75], Alzheimer disease [76] and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [77]. The latter will be a particularly interesting candidate disease because its pathogenesis depends critically not only on macrophages but also neutrophils.

The TCR-like immune receptors presented here combine the properties of innate and adaptive immunity and, like these, undergo deterioration during aging. There is an enormous amount of work ahead of us to explore the function and true complexity of this novel myeloid flexible immune system that was hidden in the shadow of lymphocytes for so long. Considering the key role of phagocytes in vertebrate host defense, it is foreseeable that this task will provide a new angle on the pathogenesis of inflammatory disease and help us to better understand the immunologic deficits that arise during aging.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Vereinte Gesellschaft für Klinische Chemie und Labormedizin (WEK).

References

- [1].Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Metschnikoff E. Untersuchungen über die intrazelluläre Verdauung bei wirbellosen Tieren. Arb Zool Inst Univ Wien. 1883;5:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Behring E, Kitasato S. Üeber das Zustandekommen der Diphtherie-Immunität und der Tetanus-Immunitat bei Thieren. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1890;16:1113–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Nathan C. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Galli SJ, Borregaard N, Wynn TA. Phenotypic and functional plasticity of cells of innate immunity: macrophages, mast cells and neutrophils. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/ni.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hirano M, Das S, Guo P, Cooper MD. The evolution of adaptive immunity in vertebrates. Adv Immunol. 2011;109:125–157. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387664-5.00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fagraeus A. Plasma cellular reaction and its relation to the formation of antibodies in vitro. Nature. 1947;159:499. doi: 10.1038/159499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mak TW. The T cell antigen receptor: “The Hunting of the Snark”. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:83–93. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737443. Suppl. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Puellmann K, Kaminski WE, Vogel M, Nebe CT, Schroeder J, Wolf H, Beham AW. From the cover: A variable immunoreceptor in a subpopulation of human neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14441–14446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603406103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Puellmann K, Beham AW, Kaminski WE. Cytokine storm and an anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2592–2593. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc062750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fuchs T, Puellmann K, Scharfenstein O, Eichner R, Stobe E, Becker A, Pechlivanidou I, Kzhyshkowska J, Gratchev A, Ganser A, Neumaier M, Beham AW, Kaminski WE. The neutrophil variable TCR-like immune receptor is expressed across the entire human life span but repertoire diversity declines in old age. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;419:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Legrand F, Driss V, Woerly G, Loiseau S, Hermann E, Fournié JJ, Héliot L, Mattot V, Soncin F, Gougeon ML, Dombrowicz D, Capron M. A functional gammadelta TCR/CD3 complex distinct from gammadeltaT cells is expressed by human eosinophils. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Beham AW, Puellmann K, Laird R, Fuchs T, Streich R, Breysach C, Raddatz D, Oniga S, Peccerella T, Findeisen P, Kzhyshkowska J, Gratchev A, Schweyer S, Saunders B, Wessels JT, Möbius W, Keane J, Becker H, Ganser A, Neumaier M, Kaminski WE. A TNF-regulated recombinatorial macrophage immune receptor implicated in granuloma formation in tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002375. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Crone M, Koch C, Simonsen M. The elusive T cell receptor. Transplant Rev. 1972;10:36–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1972.tb01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yanagi Y, Yoshikai Y, Leggett K, Clark SP, Aleksander I, Mak TW. A human T cell-specific cDNA clone encodes a protein having extensive homology to immunoglobulin chains. Nature. 1984;308:145–149. doi: 10.1038/308145a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hedrick SM, Cohen DI, Nielsen EA, Davis MM. Isolation of cDNA clones encoding T cell-specific membrane-associated proteins. Nature. 1984;308:149–153. doi: 10.1038/308149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chien Y, Becker DM, Lindsten T, Okamura M, Cohen DI, Davis MM. A third type of murine T-cell receptor gene. Nature. 1984;312:31–35. doi: 10.1038/312031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Saito H, Kranz DM, Takagaki Y, Hayday AC, Eisen HN, Tonegawa S. Complete primary structure of a heterodimeric T-cell receptor deduced from cDNA sequences. Nature. 1984;309:757–762. doi: 10.1038/309757a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hannum CH, Kappler JW, Trowbridge IS, Marrack P, Freed JH. Immunoglobulin-like nature of the alpha-chain of a human T-cell antigen/MHC receptor. Nature. 1984;312:65–67. doi: 10.1038/312065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Saito H, Kranz DM, Takagaki Y, Hayday AC, Eisen HN, Tonegawa S. A third rearranged and expressed gene in a clone of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature. 1984;312:36–40. doi: 10.1038/312036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Murre C, Waldmann RA, Morton CC, Bongiovanni KF, Waldmann TA, Shows TB, Seidman JG. Human gamma-chain genes are rearranged in leukaemic T cells and map to the short arm of chromosome 7. Nature. 1985;316:549–552. doi: 10.1038/316549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hata S, Brenner MB, Krangel MS. Identification of putative human T cell receptor delta complementary DNA clones. Science. 1987;238:678–782. doi: 10.1126/science.3499667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Loh EY, Lanier LL, Turck CW, Littman DR, Davis MM, Chien YH, Weiss A. Identification and sequence of a fourth human T cell antigen receptor chain. Nature. 1987;330:569–572. doi: 10.1038/330569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rappolee DA, Mark D, Banda MJ, Werb Z. Wound macrophages express TGF-alpha and other growth factors in vivo: analysis by mRNA phenotying. Science. 1988;241:708–712. doi: 10.1126/science.3041594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kaminski WE, Beham AW, Kzhyshkowska J, Gratchev A, Puellmann K. On the horizon: Flexible immune recognition outside lymphocytes. Immunobiology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.05.024. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bosma GC, Custer RP, Bosma MJ. A severe combined immunodeficiency mutation in the mouse. Nature. 1983;301:527–530. doi: 10.1038/301527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Philpott KL, Viney JL, Kay G, Rastan S, Gardiner EM, Chae S, Hayday AC, Owen MJ. Lymphoid development in mice congenitally lacking T cell receptor alpha beta-expressing cells. Science. 1992;256:1448–1452. doi: 10.1126/science.1604321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mombaerts P, Clarke AR, Rudnicki MA, Iacomini J, Itohara S, Lafaille JJ, Wang L, Ichikawa Y, Jaenisch R, Hooper ML, Tonegawa S. Mutations in T-cell antigen receptor genes and block thymocyte development at different stages. Nature. 1992;360:225–231. doi: 10.1038/360225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Itohara S, Mombaerts P, Lafaille JJ, Iacomini J, Nelson A, Clarke AR, Hooper ML, Farr A, Tonegawa S. T cell receptor delta gene mutant mice: independent generation of alpha beta T cells and programmed rearrangements of gamma delta TCR genes. Cell. 1993;72:337–348. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bouvier G, Watrin F, Naspetti M, Verthuy C, Naquet P, Ferrier P. Deletion of the mouse T-cell receptor beta gene enhancer blocks alphabeta T-cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7877–7881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mombaerts P, Iacomini J, Johnson RS, Herrup K, Tonegawa S, Papaioannou VE. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;68:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shinkai Y, Rathbun G, Lam KP, Oltz EM, Stewart V, Mendelsohn M, Charron J, Datta M, Young F, Stall AM, Alt FW. RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell. 1992;68:855–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lian Z, Wang L, Yamaga S, Bonds W, Beazer-Barclay Y, Kluger Y, Gerstein M, Newburger PE, Berliner N, Weissman SM. Genomic and proteomic analysis of the myeloid differentiation program. Blood. 2001;98:513–524. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lian Z, Kluger Y, Greenbaum DS, Tuck D, Gerstein M, Berliner N, Weissman SM, Newburger PE. Genomic and proteomic analysis of the myeloid differentiation program: global analysis of gene expression during induced differentiation in the MPRO cell line. Blood. 2002;100:3209–3220. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Maouche S, Poirier O, Godefroy T, Olaso R, Gut I, Collet JP, Montalescot G, Cambien F. Performance comparison of two microarray platforms to assess differential gene expression in human monocyte and macrophage cells. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:e302. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mosig S, Rennert K, Büttner P, Krause S, Lütjohann D, Soufi M, Heller R, Funke H. Monocytes of patients with familial hypercholesterolemia show alterations in cholesterol metabolism. BMC Med Genomics. 2008;1:e60. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-1-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lee SM, Gardy JL, Cheung CY, Cheung TK, Hui KP, Ip NY, Guan Y, Hancock RE, Peiris JS. Systems-level comparison of host-responses elicited by avian H5N1 and seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses in primary human macrophages. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schirmer SH, Fledderus JO, van der Laan AM, van der Pouw-Kraan TC, Moerland PD, Volger OL, Baggen JM, Böhm M, Piek JJ, Horrevoets AJ, van Royen N. Suppression of inflammatory signaling in monocytes from patients with coronary artery disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Schirmer SH, Bot PT, Fledderus JO, van der Laan AM, Volger OL, Laufs U, Böhm M, de Vries CJ, Horrevoets AJ, Piek JJ, Hoefer IE, N. van Royen N. Blocking interferon [2] stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and arteriogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:34677–34685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.164350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Borghesi L, Milcarek C. Innate versus adaptive immunity: a paradigm past its prime? Cancer Res. 2007;67:3989–3993. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ferrante A, Hii C, Hume D. Neutrophilic schizophrenia: breaching the barrier between innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:265–266. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hellerstein M, Hanley MB, Cesa D, Siler S, Papageorgopoulos C, Wieder E, Schmidt D, Hoh R, Neese R, Macallan D, Deeks S, McCune JM. Directly measured kinetics of circulating T lymphocytes in normal and HIV-1-infected humans. Nat Med. 1999;5:83–89. doi: 10.1038/4772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Solana R, Pawelec G, Tarazona R. Aging and innate immunity. Immunity. 2006;24:491–494. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Shaw AC, Joshi S, Greenwood H, Panda A, Lord JM. Aging of the innate immune system. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Panda A, Arjona A, Sapey E, Bai F, Fikrig E, Montgomery RR, Lord JM, Shaw AC. Human innate immunosenescence: causes and consequences for immunity in old age. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wessels I, Jansen J, Rink L, Uciechowski P. Immunosenescence of polymorphonuclear neutrophils. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:145–160. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chatta GS, Andrews RG, Rodger E, Schrag M, Hammond WP, Dale DC. Hematopoietic progenitors and aging: alterations in granulocytic precursors and responsiveness to recombinant human G-CSF, GM-CSF, and IL-3. J Gerontol. 1993;48:M207–212. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.5.m207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Born J, Uthgenannt D, Dodt C, Nünninghoff D, Ringvolt E, Wagner T, Fehm HL. Cytokine production and lymphocyte subpopulations in aged humans. An assessment during nocturnal sleep. Mech Ageing Dev. 1995;84:113–126. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(95)01638-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Herrero C, Sebastián C, Marqués L, Comalada M, Xaus J, Valledor AF, Lloberas J, Celada A. Immunosenescence of macrophages: reduced MHC class II gene expression. Exp Gerontol. 2002;37:389–394. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Plowden J, Renshaw-Hoelscher M, Engleman C, Katz J, Sambhara S. Innate immunity in aging: impact on macrophage function. Aging Cell. 2004;3:161–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].De Martinis M, Modesti M, Ginaldi L. Phenotypic and functional changes of circulating monocytes and polymorphonuclear leucocytes from elderly persons. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:415–420. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Stout RD, Suttles J. Immunosenescence and macrophage functional plasticity: dysregulation of macrophage function by age-associated microenvironmental changes. Immunol Rev. 2005;205:60–71. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Solana R, Tarazona R, Gayoso I, Lesur O, Dupuis G, Fulop T. Innate immunosenescence: Effect of aging on cells and receptors of the innate immune system in humans. Semin Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.04.008. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Boehmer ED, Meehan MJ, Cutro BT, Kovacs EJ. Aging negatively skews macrophage TLR2- and TLR4-mediated proinflammatory responses without affecting the IL-2-stimulated pathway. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Tasat DR, Mancuso R, O’Connor S, Molinari B. Age-dependent change in reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide generation by rat alveolar macrophages. Aging Cell. 2003;2:159–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sebastián C, Herrero C, Serra M, Lloberas J, Blasco MA, Celada A. Telomere shortening and oxidative stress in aged macrophages results in impaired STAT5a phosphorylation. J Immunol. 2009;183:2356–2364. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Renshaw M, Rockwell J, Engleman C, Gewirtz A, Katz J, Sambhara S. Cutting edge: impaired Toll-like receptor expression and function in aging. J Immunol. 2002;169:4697–4701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Herrero C, Marques L, Lloberas J, Celada A. IFN-gamma-dependent transcription of MHC class II IA is impaired in macrophages from aged mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:485–493. doi: 10.1172/JCI11696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Yager EJ, Ahmed M, Lanzer K, Randall TD, Woodland DL, Blackman MA. Age-associated decline in T cell repertoire diversity leads to holes in the repertoire and impaired immunity to influenza virus. J Exp Med. 2008;205:711–723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Rudd BD, Venturi V, Davenport MP, Nikolich-Zugich J. Evolution of the antigen-specific CD8+ TCR repertoire across the life span: evidence for clonal homogenization of the old TCR repertoire. J Immunol. 2011;186:2056–2064. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Naylor K, Li G, Vallejo AN, Lee WW, Koetz K, Bryl E, Witkowski J, Fulbright J, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. The influence of age on T cell generation and TCR diversity. J Immunol. 2005;174:7446–7452. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Goldberger AL. Non-linear dynamics for clinicians: chaos theory, fractals, and complexity at the bedside. Lancet. 1996;347:1312–1314. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90948-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Varela M, Ruiz-Esteban R, Mestre de Juan MJ. Chaos, fractals, and our concept of disease. Perspect Biol Med. 2010;53:584–595. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2010.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Goldberger AL, Amaral LA, Hausdorff JM, Ivanov P, Peng CK, Stanley HE. Fractal dynamics in physiology: alterations with disease and aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2466–2472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012579499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Fuchs T, Puellmann K, Schneider S, Kruth J, Schulze TJ, Neumaier M, Beham AW, Kaminski WE. An autoimmune double attack. Lancet. 2012;379:1364. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61939-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ross R. Atherosclerosis – an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Coffelt SB, Hughes R, Lewis CE. Tumor-associated macrophages: effectors of angiogenesis and tumor progression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1796:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Qian BZ, Li J, Zhang H, Kitamura T, Zhang J, Campion LR, Kaiser EA, Snyder LA, Pollard JW. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475:222–225. doi: 10.1038/nature10138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Netea MG, Quintin J, van der Meer JW. Trained immunity: a memory for innate host defense. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Wang C, Sanders CM, Yang Q, Schroeder HW, Jr, Wang E, Babrzadeh F, Gharizadeh B, Myers RM, Hudson JR, Jr, Davis RW, Han J. High throughput sequencing reveals a complex pattern of dynamic interrelationships among human T cell subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1518–1523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913939107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Warren RL, Freeman JD, Zeng T, Choe G, Munro S, Moore R, Webb JR, Holt RA. Exhaustive T-cell repertoire sequencing of human peripheral blood samples reveals signatures of antigen selection and a directly measured repertoire size of at least 1 million clonotypes. Genome Res. 2011;21:790–797. doi: 10.1101/gr.115428.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Bolotin DA, Mamedov IZ, Britanova OV, Zvyagin IV, Shagin D, Ustyugova SV, Turchaninova MA, Lukyanov S, Lebedev YB, Chudakov DM. Next generation sequencing for TCR repertoire profiling: platform-specific features and correction algorithms. Eur J Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/eji.201242517. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Henriksen K, Bollerslev J, Everts V, Karsdal MA. Osteoclast activity and subtypes as a function of physiology and pathology--implications for future treatments of osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2011;32:31–63. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Rezai-Zadeh K, Gate D, Gowing G, Town T. How to get from here to there: macrophage recruitment in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8:156–163. doi: 10.2174/156720511795256017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Donnelly LE, Barnes PJ. Defective phagocytosis in airways disease. Chest. 2012;141:1055–1062. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]