Abstract

Caspase-8 (encoded by the CASP-8 gene) is crucial in generating cell death signals and eliminating potentially malignant cells. Genetic variation in CASP8 may affect susceptibility to cancer. The CASP-8 −652 6N ins/del (rs3834129) polymorphism has been previously reported to influence the progression to several cancers. However, the overall reported studies have shown inconsistent conclusions. In this human genome epidemiology (HuGE) review and meta-analysis, the aim was to identify the association between CASP-8 −652 6N ins/del polymorphism and cancer risk. According to the inclusion criteria, 19 case-control studies with a total of 23,172 cancer cases and 26,532 healthy controls were retrieved. Meta-analysis results showed that the del allele, del allele carrier and ins/del genotype of −652 6N ins/del in the CASP-8 gene were negatively associated with cancer risk (OR=0.91, 95% CI=0.84–0.98, P=0.01; OR=0.88, 95% CI=0.80–0.96, P=0.005; OR=0.91, 95% CI=0.85–0.98, P<0.001; respectively, while no significant correlation was observed between the del/del genotype of −652 6N ins/del and cancer risk (OR=0.89, 95% CI=0.79–1.01, P=0.08). In the subgroup analysis by ethnicity, the meta-analysis indicated that Caucasian populations harboring the del allele, del allele carriers and ins/del genotype had a lower cancer risk (OR=0.96, 95% CI=0.93–1.00, P=0.05; OR=0.86, 95% CI=0.75–1.00, P=0.05; OR=0.91, 95% CI=0.84–0.98, P=0.01; respectively). In addition, a negative association was found between the del allele of −652 6N ins/del in the CASP-8 gene and cancer risk in the Asian population (OR=0.89, 95% CI=0.83–0.97, P=0.005). In conclusion, this meta-analysis suggests that the del allele, del allele carrier and ins/del geno-type of the −652 6N ins/del polymorphism in the CASP-8 gene may be protective factors for cancer risk.

Keywords: apoptosis, caspase-8, polymorphism, cancer risk, meta-analysis

Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, with millions of individuals succumbing to various types of cancer annually (1). Therefore, it is of utmost importance to identify anticancer prevention and treatment strategies. According to epidemiology, cell apoptosis plays a role in the incidence of cancers. Apoptosis, also known as programmed cell death, is a fundamentally important biological process triggered by a variety of stimuli, including deprivation of growth/survival factors, exposure to cytotoxic drugs or DNA damaging agents, activation of death receptors and activity of cytotoxic cells, that is involved in controlling cell number and eliminating harmful or virus-infected cells to maintain cell homeostasis (2–4). The inappropriate process of apoptosis potentially results in various pathological disorders (5). The caspase family (cysteine and aspartic proteases) is mainly involved in the regulation of cell apoptosis (6), and has two major functions: caspase-1, −4, −5 and −11, as initiator caspases, are primarily involved in the processing and activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, while caspase-2, −3, −6, −7, −8 and −9, as executor caspases, play a role in the execution phase of apoptosis (6,7). CASP activation has two dinstinct albeit converging pathways: the extrinsic or receptor-mediated pathway, and the intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway. These two pathways possess an independent group of initiator caspases despite using the same group of effector caspases (8–10). Caspase-8 (CASP-8) is essential for the extrinsic cell death pathways initiated by the TNF family members with the formation of the death-inducing signaling complex (11).

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the most common form of human genetic variation, leading to susceptibility to cancer. Findings of previous studies showed that some variants in CASP-8 gene are associated with susceptibility to various human cancers (12,13). A case-control study in a Chinese population found that CASP-8 −652 6N del/del genotypes showed a multiplicative joint effect with FasL and Fas in attenuating susceptibility to pancreatic cancer (14). However, relevant studies on −652 6N del in CASP-8 are inconclusive and inconsistent. Therefore, a human genome epidemiology (HuGE) review and meta-analysis were conducted, including the most recent and relevant articles in order to identify statistical evidence of the association between the CASP-8 −652 6N ins/del polymorphism and cancer risk that have been investigated.

Materials and methods

Literature search

An extensive electronic search of the PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, SpringerLink, CNKI and CBM databases was performed to identify relevant studies available up to May 1, 2012. The search terms used included [‘caspase-8’, ‘CASP-8’ or ‘Caspase 8’ (Mesh)] and [‘SNPs’, ‘SNP’ or ‘polymorphism, genetic’ (Mesh)] and [‘cancer’, ‘tumor’ or ‘Neoplasms’ (Mesh)]. The references in the eligible studies or textbooks were also reviewed to check through manual searches to find other potentially eligible studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The included studies had to meet the following criteria: i) case-control study focused on the associations between CASP-8 −652 6N ins/del polymorphism and cancer risk; ii) all patients diagnosed with a malignant tumor confirmed by pathological examination of the surgical specimen; iii) the frequencies of alleles or geno-types in case and control groups could be extracted; iv) the publication was in English or Chinese. Studies were excluded when they were: i) not case-control studies about CASP-8 −652 6N ins/del polymorphism and cancer risk; ii) based on incomplete data; iii) useless or overlapping data were reported; iv) meta-analyses, letters, reviews or editorial articles.

Data extraction

Using a standardized form, data from published studies were extracted independently by two reviewers to populate the necessary information. The information extracted from each of the articles included: first author, year of publication, country, language, ethnicity, study design, source of cases and controls, number of cases and controls, mean age, sample, cancer type, genotype method, allele and genotype frequency, and evidence of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in controls. In case of conflicting evaluations, an agreement was reached following a discussion with a third reviewer.

Quality assessment of included studies

Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of papers according to modified STROBE quality score systems (15,16). Forty assessment items associated with the quality appraisal were used in this meta-analysis, scores ranging from 0 to 40. Scores of 0–20, 20–30 and 30–40 were defined as low, moderate and high quality, respectively. Disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated using Review Manager Version 5.1.6 (provided by the Cochrane Collaboration, available at: http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/download) and STATA Version 12.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) software. Between-study variations and heterogeneities were estimated using Cochran’s Q-statistic (17,18) (P≤0.05 was considered to be a manifestation of statistically significant heterogeneity). The effect of heterogeneity, ranging from 0 to 100% and representing the proportion of inter-study variability that can be contributed to heterogeneity rather than to chance, was quantified using the I2 test. When a significant Q-test (P≤0.05) or I2>50% indicated that heterogeneity among studies existed, the random-effects model was employed for the meta-analysis. Otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used. To establish the effect of heterogeneity on conclusions of the meta-analyses, a subgroup analysis was carried out. We also tested whether genotype frequencies of controls were in HWE using the χ2 test. Funnel plots are often used to detect publication bias. However, due to its limitations caused by varied sample sizes and subjective reviews, Egger’s linear regression test, which measures the funnel plot’s asymmetry using a natural logarithmic scale of OR, was used to evaluate the publication bias (19). When the P-value is <0.1, publication bias is considered significant. All the P-values were two-sided. To ensure the reliability and accuracy of the results, two reviewers populated the data in the statistical software programs independently and obtained identical results.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

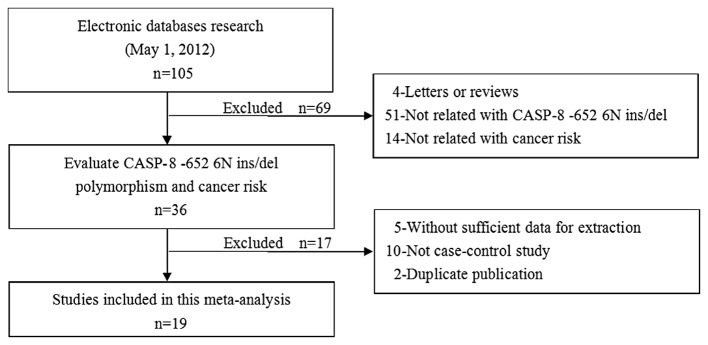

Subsequent to the initial screening a total of 105 relevant publications were identified. Nineteen studies (20–37) appeared to have met the inclusion criteria and were subjected to further examination. The flow chart of study selection is shown in Fig. 1. In the pooled analysis, a total of 23,172 cancer cases and 26,532 healthy controls from 19 studies were included and addressed. The publication year of involved studies ranged from 2006 to 2011. Twelve of these studies were conducted in Asian populations, 6 in Caucasian populations and 1 in African populations. The HWE test was performed on the genotype distribution of the controls in all the included studies, 2 of these studies were out of HWE (34,37) and the remaining studies showed to be in HWE (P>0.05). Quality scores of included studies were >20 (moderate-high quality). The characteristics and methodological quality of the included studies are shown in Table I. The genotype distribution of the CASP-8 −652 6N ins/del polymorphism in the case and control groups is shown in Table II.

Figure 1.

Flow chart shows study selection procedure. Nineteen case-control studies were included in this meta-analysis.

Table I.

Characteristics of individual studies in this meta-analysis.

| Authors (Refs.) | Year | Country | Case no.

|

Sample | Genotype method | Cancer type | Quality scores | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | Control | |||||||

| Son et al (20) | 2006 | Korea | 432 | 432 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Lung cancer | 27 |

| Sun et al (21) | 2007 | China | 4995 | 4972 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Mixed cancer | 23 |

| Cybulski et al (22) | 2008 | Poland | 618 | 531 | Blood | AS-PCR | Mixed cancer | 20 |

| Frank et al (23) | 2008 | Germany | 7753 | 7921 | Blood | FFA | Breast cancer | 23 |

| Li et al (24) | 2008 | China | 805 | 835 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Melanoma | 26 |

| Pittman et al (25) | 2008 | UK | 4016 | 3749 | Blood | AS-PCR | Colorectal cancer | 21 |

| Yang et al (14) | 2008 | China | 397 | 907 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Pancreatic cancer | 24 |

| Gangwar et al (26) | 2009 | India | 212 | 250 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Bladder cancer | 29 |

| Wang et al (27) | 2009 | China | 365 | 368 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Bladder cancer | 26 |

| Li et al (28) | 2010 | USA | 1023 | 1052 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Head and neck cancer | 26 |

| Liu et al (29) | 2010 | China | 373 | 838 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Colorectal cancer | 25 |

| Lv et al (30) | 2010 | China | 100 | 544 | Blood | TaqMan | Lymphoma | 26 |

| Srivastava et al (31) | 2010 | India | 230 | 230 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Gallbladder cancer | 24 |

| Chatterjee et al (32) | 2011 | South Africa | 445 | 1221 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Cervical cancer | 18 |

| Hart et al (33) | 2011 | Norway | 442 | 440 | Blood/tissue | TaqMan | Lung cancer | 20 |

| Kesarwani et al (34) | 2011 | India | 175 | 198 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Prostate cancer | 24 |

| Ma et al (35) | 2011 | China | 218 | 285 | Blood | Mass-Array | Ovarian cancer | 18 |

| Theodoropoulos et al (36) | 2011 | Greece | 402 | 480 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Colorectal cancer | 18 |

| Umar et al (37) | 2011 | India | 259 | 259 | Blood | PCR-RFLP | Esophageal cancer | 20 |

PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism; AS, allele specific; FFA, Fluorescent fragment analysis.

Table II.

The genotype distribution of CASP-8 −652 6N polymorphism in case and control groups.

| Authors (Refs.) | Case

|

Control

|

HWE test

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ins | del | ins/ins | ins/del | del/del | Total | ins | del | ins/ins | ins/del | del/del | χ2 | P-value | Test | |

| Son et al (20) | 432 | 654 | 210 | 247 | 160 | 25 | 432 | 659 | 205 | 249 | 161 | 22 | 0.38 | 0.54 | HWE |

| Sun et al (21) | 4938 | 7917 | 1959 | 3173 | 1571 | 194 | 4919 | 7373 | 2465 | 2771 | 1831 | 317 | 0.39 | 0.53 | HWE |

| Cybulski et al (22) | 1103 | 1184 | 1022 | 317 | 550 | 236 | 965 | 1047 | 883 | 274 | 499 | 192 | 1.68 | 0.20 | HWE |

| Frank et al (23) | 7390 | 7592 | 7188 | 1946 | 3700 | 1744 | 7693 | 7767 | 7619 | 1949 | 3869 | 1875 | 0.27 | 0.60 | HWE |

| Li et al (24) | 805 | 871 | 739 | 243 | 385 | 177 | 835 | 854 | 816 | 207 | 440 | 188 | 2.47 | 0.12 | HWE |

| Pittman et al (25) | 3879 | 3887 | 3871 | 995 | 1897 | 987 | 3661 | 3656 | 3666 | 892 | 1872 | 897 | 1.88 | 0.17 | HWE |

| Yang et al (14) | 397 | 647 | 147 | 268 | 111 | 18 | 907 | 1365 | 449 | 521 | 323 | 63 | 1.76 | 0.19 | HWE |

| Gangwar et al (26) | 212 | 326 | 98 | 121 | 84 | 7 | 250 | 367 | 133 | 133 | 101 | 16 | 0.30 | 0.58 | HWE |

| Wang et al (27) | 365 | 591 | 139 | 238 | 115 | 12 | 365 | 545 | 185 | 205 | 135 | 25 | 0.19 | 0.67 | HWE |

| Li et al (28) | 1023 | 1078 | 968 | 311 | 456 | 256 | 1052 | 1056 | 1048 | 257 | 542 | 253 | 1.54 | 0.21 | HWE |

| Liu et al (29) | 370 | 582 | 158 | 233 | 116 | 21 | 838 | 1334 | 342 | 528 | 278 | 32 | 0.38 | 0.54 | HWE |

| Lv et al (30) | 100 | 142 | 58 | 48 | 46 | 6 | 544 | 867 | 221 | 344 | 179 | 21 | 0.15 | 0.70 | HWE |

| Srivastava et al (31) | 228 | 363 | 93 | 147 | 69 | 12 | 230 | 328 | 132 | 122 | 84 | 24 | 2.66 | 0.10 | HWE |

| Chatterjee et al (32) | 445 | 455 | 435 | 102 | 251 | 92 | 1221 | 1255 | 1187 | 308 | 639 | 274 | 2.75 | 0.10 | HWE |

| Hart et al (33) | 436 | 460 | 412 | 125 | 210 | 101 | 433 | 421 | 445 | 106 | 209 | 118 | 0.50 | 0.48 | HWE |

| Kesarwani et al (34) | 170 | 244 | 96 | 86 | 72 | 12 | 198 | 301 | 95 | 109 | 83 | 6 | 4.42 | 0.04 | Non-HWE |

| Ma et al (35) | 218 | 343 | 93 | 128 | 87 | 3 | 285 | 398 | 172 | 138 | 122 | 25 | 0.07 | 0.79 | HWE |

| Theodoropoulos et al (36) | 402 | 407 | 397 | 103 | 201 | 98 | 480 | 494 | 466 | 120 | 254 | 106 | 1.68 | 0.19 | HWE |

| Umar et al (37) | 259 | 381 | 137 | 139 | 103 | 17 | 259 | 369 | 149 | 138 | 93 | 28 | 3.97 | 0.05 | Non-HWE |

CASP-8, caspase-8; HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Main results and subgroup analysis

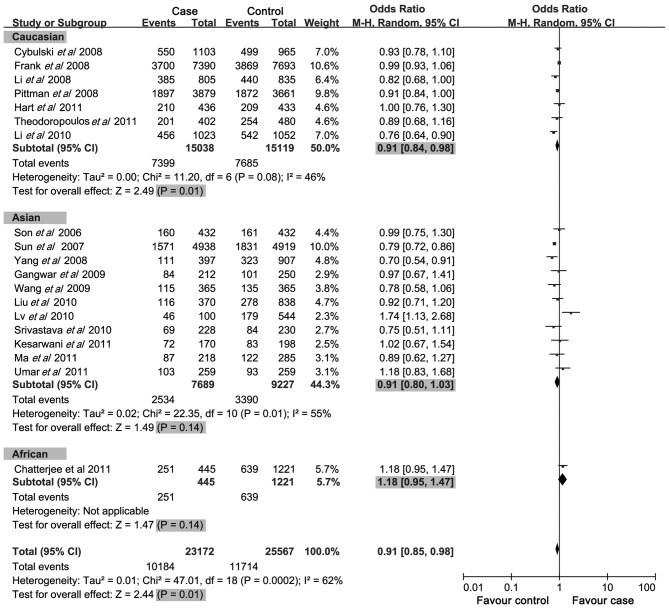

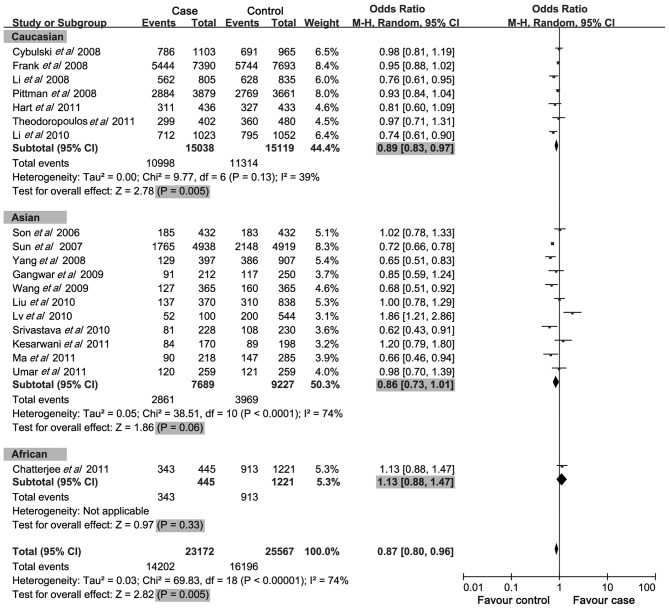

A summary of the meta-analysis findings of the association between CASP-8 −652 6N ins/del polymorphism and cancer risk is provided in Table III. The meta-analysis results showed that the del allele, del allele carrier and ins/del genotypes of −652 6N ins/del in CASP-8 gene were negatively associated with cancer risk (OR=0.91, 95% CI=0.84–0.98, P=0.01; OR=0.88, 95% CI=0.80–0.96, P=0.005; OR=0.91, 95% CI=0.85–0.98, P<0.001; respectively) (Figs. 2–4), while no significant correlation was observed between the del/del genotypes of −652 6N ins/del and cancer risk (OR=0.89, 95% CI=0.79–1.01, P=0.08). In the subgroup analysis by ethnicity, we found that the del allele of −652 6N ins/del was a protective factor for cancer risk in the Caucasian and Asian populations (OR=0.96, 95% CI=0.93–1.00, P=0.05; OR=0.86, 95% CI=0.75–1.00, P=0.05; respectively), although not in the African population (OR=1.01, 95% CI=0.87–1.18, P=0.891). For the del allele carrier of −652 6N ins/del polymorphism, negative associations with cancer risk were found in the Caucasian population (OR=0.89, 95% CI=0.83–0.97, P=0.005), but not in the Asian and African populations (OR=0.86, 95% CI=0.73–1.01, P=0.06; OR=1.13, 95% CI=0.88–1.47, P=0.33; respectively). Notably, no associations were found between the del/del genotype (variant homozygote) of the −652 6N ins/del polymorphism and cancer risk in the three populations (OR=0.89, 95% CI=0.79–1.10, P=0.08). However, with regards to the ins/del genotype (heterozygote) of the −652 6N ins/del polymorphism, protective associations with cancer risk were found in the Caucasian population (OR=0.91, 95% CI=0.84–0.98, P=0.01), whereas no correlation was found in the Asian and African populations (OR=0.91, 95% CI=0.80–1.03, P=0.14; OR=1.18, 95% CI=0.95–1.47, P=0.14; respectively).

Table III.

Meta-analysis of the association between the −652 6N ins>del polymorphism in CASP-8 and cancer risk.

| Subgroup | Case no./N | Control no./N | OR (95% CI) | P-value | Effect model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| del allele | 18220/46344 | 20678/51134 | 0.91 (0.84–0.98) | 0.01 | Random |

| Caucasian | 14597/30076 | 14943/30238 | 0.96 (0.93–1.00) | 0.05 | |

| Asian | 3188/15378 | 4548/18454 | 0.86 (0.75–1.00) | 0.05 | |

| African | 435/890 | 1187/2442 | 1.01 (0.87–1.18) | 0.89 | |

| del allele carrier | 14202/23172 | 16196/25567 | 0.87 (0.80–0.96) | 0.005 | Random |

| Caucasian | 10998/15038 | 11314/15119 | 0.89 (0.83–0.97) | 0.005 | |

| Asian | 2861/7689 | 3969/9227 | 0.86 (0.73–1.01) | 0.06 | |

| African | 343/445 | 913/1221 | 1.13 (0.88–1.47) | 0.33 | |

| del/del | 4018/23172 | 4482/25567 | 0.89 (0.79–1.01) | 0.08 | Random |

| Caucasian | 3599/15308 | 3629/15119 | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 0.90 | |

| Asian | 327/7689 | 579/9227 | 0.73 (0.53–1.01) | 0.06 | |

| African | 92/445 | 274/1221 | 0.90 (0.69–1.18) | 0.44 | |

| ins/del | 10184/23172 | 11741/25567 | 0.91 (0.85–0.98) | <0.001 | Random |

| Caucasian | 7399/125038 | 7685/15119 | 0.91 (0.84–0.98) | 0.01 | |

| Asian | 2534/7689 | 3390/9227 | 0.91 (0.80–1.03) | 0.14 | |

| African | 251/445 | 639/1221 | 1.18 (0.95–1.47) | 0.14 |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Associations between del allele of the −652 6N ins/del polymorphism and cancer risk.

Figure 4.

Associations between the ins/del genotype of the −652 6N ins/del polymorphism and cancer risk.

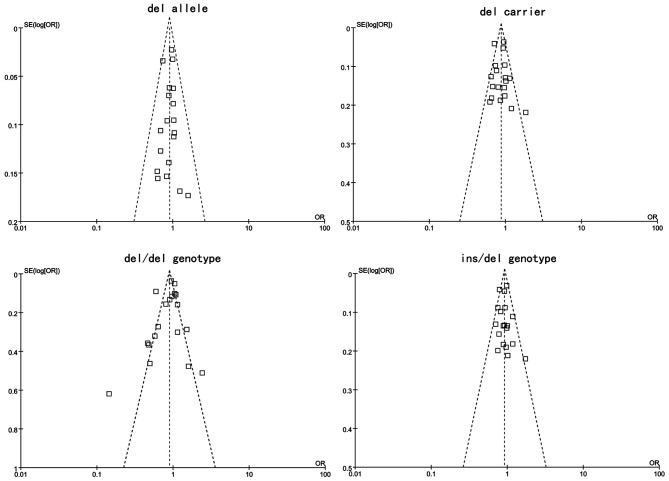

Publication bias

Publication bias of the literature was accessed by Begger’s funnel plot and Egger’s linear regression test. Egger’s linear regression test was used to measure the asymmetry of the funnel plot. The graphical funnel plots of included studies appeared to be symmetrical (Fig. 5). Egger’s test also showed that there was no statistical significance for all evaluations of publication bias (all P>0.05). Findings of Egger’s publication bias test are shown in Table IV.

Figure 5.

Begger’s funnel plot of publication bias.

Table IV.

Evaluation of publication bias by Egger’s linear regression test.

| SNP | Coefficient | SE | t | P-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| del allele | −0.298 | 0.932 | −0.320 | 0.753 | (−2.265, 1.669) |

| del carrier | 0.375 | 0.834 | 0.450 | 0.658 | (−1.384, 2.135) |

| del/del genotype | −0.745 | 0.645 | −1.160 | 0.264 | (−2.105, 0.615) |

| ins/del genotype | 0.192 | 0.664 | 0.290 | 0.776 | (−1.208, 1.592) |

SE, standard error; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

CASP-8, located on chromosome 2q33–q34, encoded by the CASP-8 gene, is a caspase protein that plays a key role in the execution-phase of cell apoptosis (28). When induced by Fas and various apoptotic stimuli, this protein is involved in apoptosis (29). Caspase-8 is known to activate during death receptor-initiated apoptosis, inducing apoptosis and maintaining immune homeostasis and immune surveillance, while the single genetic variants in CASP-8 and their function in human cancer susceptibility remain to be elucidated (21). The −652 6N ins/del (rs3834129), a common SNP in the CASP-8 gene, is strongly associated with the CASP-8 expression. Investigators have reported a correlation between the −652 6N ins/del polymorphism and susceptibility to various types of cancer. Sun et al observed that the CASP-8 −652 6N ins/del allele was associated with a reduced risk of developing different types of human cancer, including lung, esophageal, colorectal, cervical and breast cancer, as well as gastric cancer, indicating that this variant allele may confer protection against multiple cancers (21). Frank et al showed that the CASP-8 −652 6N ins/del variant has no significant effect on breast cancer risk in Europeans (23). In their study, Li et al observed that the CASP-8 −652 6N ins/del variant genotypes (ins/del, ins/del+del/del) were associated with significantly lower cutaneous melanoma risk than were the ins/ins genotypes (24). In our study, we examined the association of the −652 6N ins/del polymorphism in the CASP-8 gene with the risk for cancer by meta-analysis. A negative association was observed between the del allele, del allele carrier and ins/del genotype of the −652 6N ins/del polymorphism in CASP-8 gene and cancer risk. In the stratified analysis by ethnicity, Caucasians who harbored the ins/del genotypes or del allele or del allele carrier were found to exhibit a significantly lower risk for cancer. In addition, a negative association was also found between the del allele of −652 6N ins/del in CASP-8 gene and cancer risk in the Asian population.

Limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, although the funnel plot and Egger’s test did not show any publication bias, selection bias may have occurred because only studies published in English or Chinese were included. Second, the control subjects of the present study might not be representative of the general population, necessitating well-designed population-based studies with large sample sizes and detailed exposure information to validate our findings. Third, there was significant between-study heterogeneity from studies of the −652 6N ins/del polymorphism, while the geno-type distribution also showed deviation from HWE in some studies. Fourth, our meta-analysis was based on unadjusted OR estimates as not all published studies presented adjusted ORs, or when they did, the ORs were not adjusted by the same potential confounders, such as age, gender, ethnicity and exposures. In addition, our analysis did not consider the possibility of gene-gene or SNP-SNP interactions or the possibility of linkage disequilibrium between polymorphisms. Therefore, our conclusions should be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, findings of this study have shown a common insertion-deletion variation in the promoter region of the CASP-8 gene as a low penetrance susceptibility locus for certain common types of human cancers. The del allele, del allele carrier and ins/del genotype of the −652 6N ins/del polymorphism in CASP-8 gene may serve as protective factors for cancer risk. However, these findings should be validated by large-scale, prospective studies investigating more diverse ethnic groups and more detailed environmental exposure data.

Figure 3.

Associations between the del allele carrier of the −652 6N ins/del polymorphism and cancer risk.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank J.L. Liu (MedChina medical information service Co., Ltd.) for his valuable contribution and kindly revising the manuscript.

References

- 1.He X, Chang S, Zhang J, Zhao Q, Xiang H, Kusonmano K, Yang L, Sun ZS, Yang H, Wang J. MethyCancer: the database of human DNA methylation and cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D836–D841. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salvesen GS, Abrams JM. Caspase activation - stepping on the gas or releasing the brakes? Lessons from humans and flies. Oncogene. 2004;23:2774–2784. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi Y. Caspase activation, inhibition, and reactivation: a mechanistic view. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1979–1987. doi: 10.1110/ps.04789804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar S. Caspase function in programmed cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:32–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedlander RM. Apoptosis and caspases in neurodegenerative diseases. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1365–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar S, Dorstyn L. Analysing caspase activation and caspase activity in apoptotic cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;559:3–17. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-017-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel RM. Caspases at the crossroads of immune-cell life and death. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:308–317. doi: 10.1038/nri1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Degterev A, Boyce M, Yuan J. A decade of caspases. Oncogene. 2003;22:8543–8567. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodmer JL, Holler N, Reynard S, Vinciguerra P, Schneider P, Juo P, Blenis J, Tschopp J. TRAIL receptor-2 signals apoptosis through FADD and caspase-8. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:241–243. doi: 10.1038/35008667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM. Apoptosis control by death and decoy receptors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danial NN, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death: critical control points. Cell. 2004;116:205–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Miao X, Sun T, Tan W, Qu S, Xiong P, Zhou Y, Lin D. Functional polymorphisms in cell death pathway genes FAS and FASL contribute to risk of lung cancer. J Med Genet. 2005;42:479–484. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.030106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacPherson G, Healey CS, Teare MD, Balasubramanian SP, Reed MW, Pharoah PD, Ponder BA, Meuth M, Bhattacharyya NP, Cox A. Association of a common variant of the CASP8 gene with reduced risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;24:1866–1869. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang M, Sun T, Wang L, Yu D, Zhang X, Miao X, Liu J, Zhao D, Li H, Tan W, Lin D. Functional variants in cell death pathway genes and risk of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3230–3236. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology. 2007;18:800–804. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Liu JL, Zhang YJ, Wang H. Association between HLA-B*27 polymorphisms and ankylosing spondylitis in Han populations: a meta-analysis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:285–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zintzaras E, Ioannidis JP. Heterogeneity testing in meta-analysis of genome searches. Genet Epidemiol. 2005;28:123–137. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:676–680. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Son JW, Kang HK, Chae MH, Choi JE, Park JM, Lee WK, Kim CH, Kim DS, Kam S, Kang YM, Park JY. Polymorphisms in the caspase-8 gene and the risk of lung cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;169:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun T, Gao Y, Tan W, Ma S, Shi Y, Yao J, Guo Y, Yang M, Zhang X, Zhang Q, et al. A six-nucleotide insertion-deletion polymorphism in the CASP8 promoter is associated with susceptibility to multiple cancers. Nat Genet. 2007;39:605–613. doi: 10.1038/ng2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cybulski C, Wokołorczyk D, Gliniewicz B, Sikorski A, Górski B, Jakubowska A, Huzarski T, Byrski T, Debniak T, Gronwald J, et al. A six-nucleotide deletion in the CASP8 promoter is not associated with a susceptibility to breast and prostate cancers in the Polish population. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:367–368. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9864-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frank B, Rigas SH, Bermejo JL, Wiestler M, Wagner K, Hemminki K, Reed MW, Sutter C, Wappenschmidt B, Balasubramanian SP, et al. The CASP8 −652 6N del promoter polymorphism and breast cancer risk: a multicenter study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111:139–144. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9752-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C, Zhao H, Hu Z, Liu Z, Wang LE, Gershenwald JE, Prieto VG, Lee JE, Duvic M, Grimm EA, Wei Q. Genetic variants and haplotypes of the caspase-8 and caspase-10 genes contribute to susceptibility to cutaneous melanoma. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:1443–1451. doi: 10.1002/humu.20803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pittman AM, Broderick P, Sullivan K, Fielding S, Webb E, Penegar S, Tomlinson I, Houlston RS. CASP8 variants D302H and −652 6N ins/del do not influence the risk of colorectal cancer in the United Kingdom population. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1434–1436. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gangwar R, Mandhani A, Mittal RD. Caspase 9 and caspase 8 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to bladder cancer in north Indian population. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2028–2034. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang M, Zhang Z, Tian Y, Shao J, Zhang Z. A six-nucleotide insertion-deletion polymorphism in the CASP8 promoter associated with risk and progression of bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2567–2572. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C, Lu J, Liu Z, Wang LE, Zhao H, El-Naggar AK, Sturgis EM, Wei Q. The six-nucleotide deletion/insertion variant in the CASP8 promoter region is inversely associated with risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:246–253. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu B, Zhang Y, Jin M, Ni Q, Liang X, Ma X, Yao K, Li Q, Chen K. Association of selected polymorphisms of CCND1, p21, and caspase8 with colorectal cancer risk. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49:75–84. doi: 10.1002/mc.20579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lv Z. Genetic polymorphisms in CASP8, Fas and Fas ligand and the risk of peripheral T-cell lymphoma and the relationship between the genetic polymorphisms and the clinical characteristics and prognosis. Peking Union Medical College Observational Studies. Epidemiology. 2010;18:800–804. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Mittal B. Caspase-8 polymorphisms and risk of gallbladder cancer in a northern Indian population. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49:684–692. doi: 10.1002/mc.20641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chatterjee K, Williamson AL, Hoffman M, Dandara C. CASP8 promoter polymorphism is associated with high-risk HPV types and abnormal cytology but not with cervical cancer. J Med Virol. 2011;83:630–636. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hart K, Landvik NE, Lind H, Skaug V, Haugen A, Zienolddiny S. A combination of functional polymorphisms in the CASP8, MMP1, IL10 and SEPS1 genes affects risk of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2011;71:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kesarwani P, Mandal RK, Maheshwari R, Mittal RD. Influence of caspases 8 and 9 gene promoter polymorphism on prostate cancer susceptibility and early development of hormone refractory prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2011;107:471–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma X, Zhang J, Liu S, Huang Y, Chen B, Wang D. Polymorphisms in the CASP8 gene and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:554–559. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Theodoropoulos GE, Gazouli M, Vaiopoulou A, Leandrou M, Nikouli S, Vassou E, Kouraklis G, Nikiteas N. Poly morphisms of caspase 8 and caspase 9 gene and colorectal cancer susceptibility and prognosis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:1113–1118. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Umar M, Upadhyay R, Kumar S, Ghoshal UC, Mittal B. CASP8 −652 6N del and CASP8 IVS12-19G>A gene polymorphisms and susceptibility/prognosis of ESCC: a case control study in northern Indian population. J Surg Oncol. 2011;103:716–723. doi: 10.1002/jso.21881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]