Abstract

Transformed (cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter [35S]) tobacco (Nicotiana plumbaginifolia L.) plants constitutively expressing nitrate reductase (NR) and untransformed controls were subjected to drought for 5 d. Drought-induced changes in biomass accumulation and photosynthesis were comparable in both lines of plants. After 4 d of water deprivation, a large increase in the ratio of shoot dry weight to fresh weight was observed, together with a decrease in the rate of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation. Foliar sucrose increased in both lines during water stress, but hexoses increased only in leaves from untransformed controls. Foliar NO3− decreased rapidly in both lines and was halved within 2 d of the onset of water deprivation. Total foliar amino acids decreased in leaves of both lines following water deprivation. After 4 d of water deprivation no NR activity could be detected in leaves of untransformed plants, whereas about 50% of the original activity remained in the leaves of the 35S-NR transformants. NR mRNA was much more stable than NR activity. NR mRNA abundance increased in the leaves of the 35S-NR plants and remained constant in controls for the first 3 d of drought. On the 4th d, however, NR mRNA suddenly decreased in both lines. Rehydration at d 3 caused rapid recovery (within 24 h) of 35S-NR transcripts, but no recovery was observed in the controls. The phosphorylation state of the protein was unchanged by long-term drought. There was a strong correlation between maximal extractable NR activity and ambient photosynthesis in both lines. We conclude that drought first causes increased NR protein turnover and then accelerates NR mRNA turnover. Constitutive NR expression temporarily delayed drought-induced losses in NR activity. 35S-NR expression may therefore allow more rapid recovery of N assimilation following short-term water deficit.

C and N metabolism are co-regulated in higher plants. Energy and C skeletons required for N assimilation are provided either directly or indirectly (via Suc) by photosynthesis. A high rate of CO2 assimilation favors a high rate of N assimilation and vice versa (Ferrario et al., 1995). Molecular and metabolic controls are implicated in the C to N interaction, involving reciprocal regulation between the pathways of C and N assimilation (Champigny and Foyer, 1992). The present study concerns the regulation of NR, the first enzyme of primary N assimilation in plants. This enzyme is regulated at the transcriptional level by the availability of the substrate NO3− and by the end product of the N assimilation pathway, Gln. NR activity is also regulated posttranscriptionally by a phosphorylation-dephosphorylation mechanism. The dephosphorylated and phosphorylated NR proteins are equally active, but phosphorylation sensitizes the enzyme to inhibition by an inhibitory 14–3-3 protein (NIP) in the presence of Mg2+ (Glaab and Kaiser, 1995; MacKintosh et al., 1995). Both types of NR regulation respond to the changes in C metabolism, since transcription is stimulated by Suc (Cheng et al., 1992; Vincentz et al., 1993) and NR inhibition by protein phosphorylation is stimulated by low rates of C fixation (Kaiser and Förster, 1989).

Nutrient deficiencies are an intrinsic feature of water deficits in natural and controlled environments (Talouizite and Champigny, 1988; Larsson et al., 1989; Larsson, 1992; Pugnaire and Chapin, 1992; Beyrouty et al., 1994; Brewitz et al., 1996). The loss of transpiration and turgor causes a decrease in NO3− absorption by the roots and in transport from the roots to the leaves (Shaner and Boyer, 1976; Larsson, 1992). NO3− availability then limits NO3− assimilation. NR can be inhibited soon after the onset of water deprivation (Plaut, 1974), but Gln synthetase and other related enzymes are relatively unaffected (Becker and Fock, 1986a, 1986b; Foyer et al., 1998). Drought-induced decreases in foliar N have been shown to specifically limit the capacity for recovery from water deficits in prairie grasses (Heckathorn and De Lucia, 1994, 1995). In such species decreases in foliar N of up to 40% induced by water stress persisted long after water had been restored to the plants (Heckathorn and De Lucia, 1994, 1995). As a direct result of this N deficit, photosynthesis was impaired, but photosynthesis and leaf N recovered in parallel once water was restored to the plants (Heckathorn et al., 1997).

Many posttranscriptional control mechanisms respond to water stress, including mRNA processing, transcript stability, translation efficiency, and protein turnover (Ingram and Bartels, 1996). Protein kinases involved in the transcriptional regulation of protein synthesis are induced by water stress in Arabidopsis thaliana (Urao et al., 1994). Proteolytic activity increases during drought, and enhanced protease activity is implicated in the acceleration of the protein turnover observed under these conditions. Consequently, typical proteinogenic amino acids and Pro accumulate in water-stressed plants (Fukutoku and Yamada, 1984).

An important question arises concerning the molecular basis for drought-induced decreases in NR activity (Foyer et al., 1998). Decreased NO3−availability will inhibit NR gene transcription and decrease the stability of NR mRNAs. It could also affect other factors such as posttranscriptional controls. In maize leaves NR gene transcription is specifically and rapidly inhibited by water stress (Foyer et al., 1998). It was therefore of interest to study the responses of NR in water-stressed tobacco (Nicotiana plumbaginifolia) plants in which the native NR gene had been replaced by a 35S-NR cDNA construct (Vincentz and Caboche, 1991). In these transformants NR gene expression is constitutive and should not respond to water deficits via metabolite-mediated changes in gene expression.

Other effects of metabolites such as NO3− on NR mRNA stability or protein turnover are still operative and the NR protein remains posttranscriptionally regulated by phosphorylation and by proteolysis in these plants (Vincentz and Caboche, 1991; Vincentz et al., 1993; Ferrario et al., 1995, 1996; Nussaume et al., 1995). The present study involved the application of water stress to 35S-NR transformants, which are well characterized and provide an unparalleled opportunity to advance the understanding of the regulation of NR activity in the drought response in plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Untransformed and transformed (35S-NR) tobacco (Nicotiana plumbaginifolia; Vincentz and Caboche, 1991) plants were grown in pots in a growth chamber with a 16-h photoperiod at a temperature of 23°C day/18°C night at 170 μmol m−2 s−1 irradiance. The plants were supplied daily with a complete nutrient solution containing 10 mm NO3− and 2 mm NH4+ (Coïc and Lesaint, 1975). When the plants reached 7 weeks of age, irrigation was discontinued for a period of 5 d for 12 plants of each type (water-stressed plants). Six plants of each type continued to receive irrigation (control plants). Three days after ceasing irrigation, six water-stressed plants of each line were rewatered with the complete nutrient solution (rehydrated plants). Each day during water stress, the fourth leaf from the apex was harvested (the length of the first leaf from the apex was ≥1 cm).

For each treatment, leaves from one-half of the plants (three plants) were harvested and pooled to study leaves at similar developmental states. Leaves were harvested 3 h after the beginning of the photoperiod and immediately frozen in liquid N and then reduced to a fine powder and stored at −80°C until they were used for biochemical analyses. An aliquot of this fine powder was then lyophilized for the extraction of amino acids.

All experiments were carried out three times. In the first two experiments leaves were used for biochemical analyses as well as photosynthesis and biomass measurements.

Statistics

Values given for biomass and photosynthesis measurements were

obtained from a minimum of three leaves per plant from between 3 and 10

plants per line depending on the experiment (see tables and figure

legends). The results are given as the mean values for each population

with the se = ςn/

− 1, where ςn is the

sd. For biochemical analyses all of the leaves of 3 plants

were pooled. The values given for these analyses represent the means of

the leaves of 3 pooled plants.

− 1, where ςn is the

sd. For biochemical analyses all of the leaves of 3 plants

were pooled. The values given for these analyses represent the means of

the leaves of 3 pooled plants.

Biochemical Analyses

NR Activity

NR was extracted from an aliquot of the leaf powder stored at −80°C. The extraction buffer, which consisted of 50 mm Mops-KOH, pH 7.8, 5 mm NaF, 1 μm Na2MoO4, 10 μm FAD, 1 μm leupeptin, 1 μm microcystin, 0.2 g/g fresh weight PVP, 2 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 5 mm EDTA, was added to the leaf powder. A 50-μL aliquot of the uncentrifuged crude extract was retained for chlorophyll determination. The crude homogenate was then centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000g and 4°C. The NR activity and the NO3− content in the supernatant were assayed immediately. The maximal NR activity (unphosphorylated form) was measured in the presence of 5 mm EDTA. The activity of the unphosphorylated form was determined in 10 mm MgCl2. The reaction mixture consisted of 50 mm Mops-KOH buffer, pH 7.5, containing 1 mm NaF, 10 mm KNO3, 0.17 mm NADH, and either 10 mm MgCl2 or 5 mm EDTA. The reaction was stopped after 8 or 16 min by the addition of an equal volume of sulfanilamide (1%, w/v in 3 n HCl) followed by n-napthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride (0.02%, w/v), and the A540 was measured. The activation state of NR is defined as the activity measured in the presence of 10 mm MgCl2 divided by the activity measured in the presence of 5 mm EDTA (expressed as a percentage).

RNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted from frozen material. The extraction medium consisted of phenol/100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 m LiCl, 10 mm EDTA, 1% SDS/chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1, v/v) at a ratio of 1:1:1 (v/v/v). Extracts were incubated at 80°C as described by Verwoerd et al. (1989). The aqueous phases, collected by centrifugation at 20,000g for 5 min, were incubated with an equal volume of 4 m LiCl overnight at 0°C. Total precipitated RNA was then collected by centrifugation at 20,000g for 30 min and dissolved in an aqueous solution of 1% diethylpyrocarbonate. RNA was precipitated by incubation with 0.3 m sodium acetate, pH 5.6, overnight at −20°C. The precipitated RNA was collected by centrifugation at 20,000g for 20 min and resuspended in 1% diethylpyrocarbonate. Concentrations of RNA were estimated spectrophotometrically at 260 nm.

Northern Analysis

The extracted RNA was separated by electrophoresis in 1.3% agarose gels containing 17% formaldehyde (Maniatis et al., 1982) and transferred to nylon hybridization-transfer membranes (Genescreen Biotechnology Systems, NEN Research Products, Boston, MA) and cross-linked at 80°C for 2 h. Hybridization with 32P-labeled NR and β-ATPase cDNA probes was performed in 50% formamide, 0.1% SDS, 0.9 m NaCl, 0.9 m Na3PO4, 5 mm EDTA (pH 7.4), 5× Denhardt's solution (0.1% Ficoll [type 400, Pharmacia], 0.1% PVP, and 0.1% BSA), and 1 mg/100 mL denatured salmon-sperm DNA. The membranes were incubated overnight at 42°C and then washed twice in 2× SSC (1× SSC = 0.15 m NaCl and 15 mm sodium citrate) and 0.1% SDS. They were then incubated with 0.2× SSC and 1% SDS at 65°C for 5 min as described by Maniatis et al. (1982).

For the second hybridization with an ATPase probe, the membranes were initially washed in 0.1× SSC and 0.1% SDS for 3 h. Relative mRNA amounts were determined by densitometric scanning of the autoradiograms (Power Look II scanner, UMAX Data Systems, Taiwan) and an advanced quantifier (J-D Match, BioImage Systems Corp., Ann Arbor, MI). The NR probe consisted of a 1.6-kb internal EcoRI tobacco nia2 cDNA fragment as described by Vaucheret et al. (1989). The probe used for detection of the nuclear-encoded β-subunit of the mitochondrial ATPase was obtained from N. plumbaginifolia as described by Bountry and Chua (1985).

Carbohydrate Analysis

Carbohydrates were extracted in 1 m HClO4 from the leaf powder that had been stored at −80°C. The uncentrifuged crude extract was retained for assay of pheophytin and the rest was centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000g and 4°C. The pellet was used for starch determination. The supernatants (500 μL) were neutralized with 200 μL of 0.5 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 60 μL of 5 m K2CO3. The precipitate was removed by centrifugation for 5 min at 12,000g, and Suc, Glc, and Fru were analyzed enzymatically in the supernatant for 5 min at 12,000g (Galtier et al., 1995).

For starch determination, the pellet was resuspended in water and incubated at 100°C for 2 h following hydrolysis by α-amylase and amyloglucosidase in 20 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.6, for 3 h at 50°C. The Glc formed was assayed as above (Galtier et al., 1995).

Amino Acid Analysis

Total amino acids were extracted as described for the carbohydrates and determined by the Rosen colorimetric method (Rosen, 1957).

For determination of amino acid composition, amino acids were extracted from the lyophilized powder with 2% 5-sulfosalicylic acid (10 mg dry weight mL−1). The crude extracts were centrifuged at 12,000g for 5 min, and an aliquot of the supernatant was analyzed by ion-exchange chromatography (model LC5001 analyzer, Biotronics, Lowell, MA; Rochat and Boutin, 1989); physiological program run with lithium citrate buffers and detection at A570 and A440 after postcolumn derivatization with ninhydrin (Rochat and Boutin, 1989).

Determinations of NO3− and Chlorophyll

NO3− content was analyzed in the supernatant from the leaf extracts for NR activity according to the method of Cataldo et al. (1975). Chlorophyll (from the same extracts) and pheophytin (extracts for carbohydrates) were assayed as described by Arnon (1949).

Photosynthesis

The rate of net CO2 assimilation, the stomatal resistance, and the transpiration of attached tobacco leaves were measured using an IR gas analyzer (model LCA4, Analytical Development Co., Hoddesdon, UK).

RESULTS

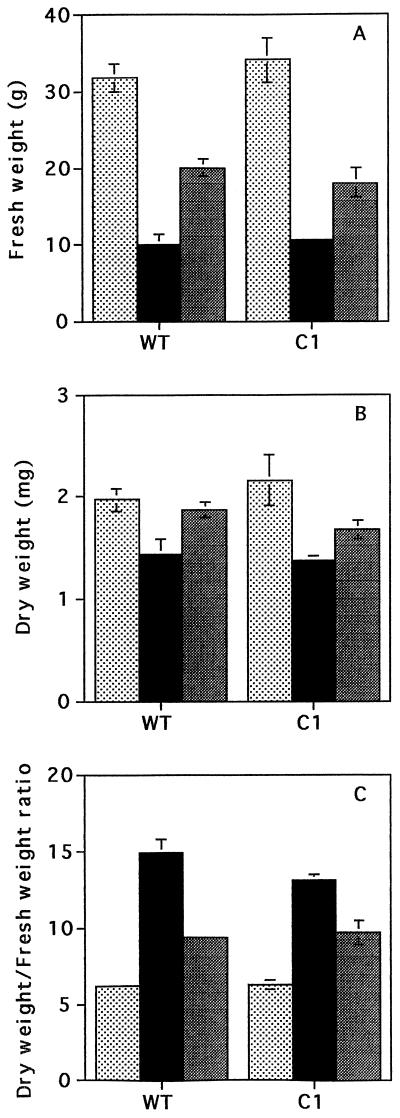

Biomass

After 5 d of water deprivation, the fresh weight accumulation in the shoot was decreased (75%) relative to that of the plants that were continuously irrigated (Fig. 1A). This decrease in biomass accumulation included water loss from the plant tissues as demonstrated by the large increase in the ratio of dry weight to fresh weight (Fig. 1C). When determined as dry weight, biomass accumulation was decreased in the shoot by approximately 30% compared with continuously irrigated plants (Fig. 1B). Since 5 d of drought caused such severe water loss from the plants that they were unable to recover following restoration of the water supply (data not shown), plants deprived of water for 3 or 4 d were used in the following experiments. When plants deprived of water for 3 d were rehydrated, biomass was increased after 2 d compared with those deprived of water for the whole experimental period (Fig. 1), but no differences were observed between the two plant lines under these conditions. No differences in biomass were found between the two lines during drought or following rehydration. Leaf samples were selected at random from the plant populations for the following measurements.

Figure 1.

Biomass accumulation in well-irrigated control plants (stippled bars), in plants deprived of water for 5 d (black bars), and in plants deprived of water for 3 d and subsequently rehydrated for 2 d (gray bars). Effects on shoot biomass (A), shoot dry weight (B), and shoot dry weight to fresh weight ratio (C) were measured in untransformed N. plumbaginifolia (WT) and 35S-NR transformants (C1).

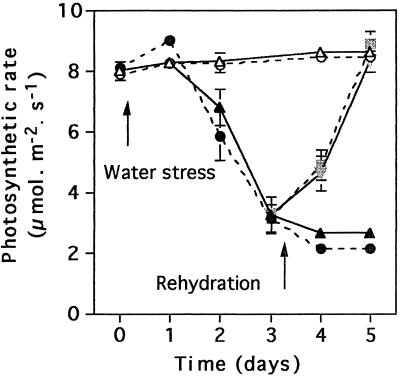

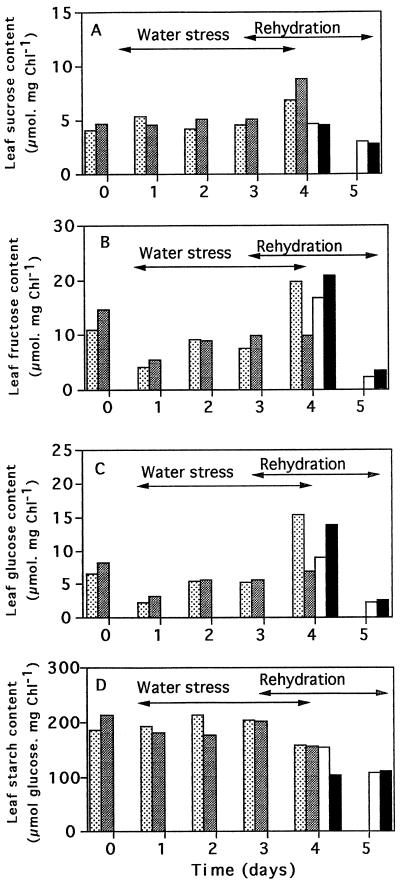

Photosynthesis and Foliar Carbohydrate Contents

Photosynthetic rates (Fig. 2) decreased from the 2nd d of water deprivation, reaching a minimum (30% of the initial value) on the 4th d in both tobacco lines. Rehydration at d 3 allowed recovery of photosynthetic activity to control rates within 2 d, suggesting that the dehydrated state was not irreversible at this stage (Fig. 2). Foliar carbohydrate contents were relatively constant over the first 3 d of the experiment (Fig. 3). On d 4 of water stress, however, Suc was increased and starch was decreased in both lines of plants (Fig. 3A). On d 4 of water deprivation, foliar hexose contents also increased but only in the untransformed plants (Fig. 3, B and C). Rehydration at d 3 caused a rapid but transient increase in leaf hexoses in both lines, whereas Suc and starch contents decreased.

Figure 2.

The effect of water deprivation (•, ▴) and rehydration (shaded symbols) compared with well-watered conditions (○, ▵) on ambient photosynthesis in untransformed (circles and dotted lines) N. plumbaginifolia and 35S-NR transformants (triangles and bold lines).

Figure 3.

The effect of water deprivation on the carbohydrate contents of leaves of untransformed N. plumbaginifolia (stippled bars) and of 35S-NR transformants (shaded bars). Foliar Suc (A), Fru (B), Glc (C), and starch (D) were measured in plants deprived of water for 4 d. The effect of rehydration on d 3 untransformed N. plumbaginifolia (white bars) and 35S-NR transformants (black bars) is also shown. Chl, Chlorophyll.

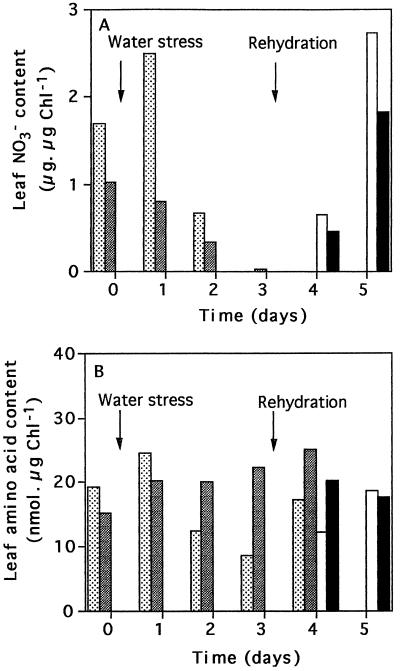

Foliar NO3− Content

In the absence of water deficit, the foliar NO3− content was higher in the leaves of untransformed plants than in those of the 35S-NR transformants, which is consistent with previously published observations (Ferrario et al., 1996). NO3− decreased on the 2nd d of drought in the leaves of both lines as a result of water stress (to a value of 50% of the irrigated controls in less than 2 d). Rehydration at d 3 induced a rapid increase in the NO3− content of the leaves (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

The effect of water deprivation on the foliar NO3− content (A) and on foliar amino acid accumulation (B) in untransformed N. plumbaginifolia (stippled bars) and in 35S-NR transformants (shaded bars). The effect of rehydration after 3 d of water stress in untransformed N. plumbaginifolia (white bars) and in 35S-NR transformants (black bars) is also shown. Chl, Chlorophyll.

Total Foliar Amino Acids

The amino acid and Gln contents of the leaves of the well-watered 35S-NR plants were higher than those of the untransformed controls (Fig. 4; Table I), as has been reported previously (Quilleré et al., 1994). Water deprivation caused a decrease in total foliar leaf amino acid contents of both the untransformed and 35S-NR plants (Fig. 4B). During the 1st d of water deprivation, however, the amino acid content of the leaves of the 35S-NR plants was much higher than that of the untransformed controls (Fig. 4B). As the duration of water stress increased, the foliar amino acid content of the 35S-NR plants dramatically decreased such that similar values were obtained in both lines by d 2 (Fig. 4B). Rehydration after 3 d caused an increase in foliar amino acids (within 24 h), but there were no longer differences between the two lines. Water deficit induced a decrease in all amino acids (Table I). The high Gln content observed in the leaves of the well-watered 35S-NR plants was maintained on the 1st d of water stress (Table I), whereas the Gln pool decreased in the leaves of the untransformed controls. Rehydration increased Gln and other amino acids in both lines (Table I).

Table I.

Foliar amino acid composition in the 35S-NR (C1) and untransformed tobacco (WT) lines during water deprivation and rehydration

| Time (d) | Water Stress

|

Rehydration

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

|||||||

| WT | C1 | WT | C1 | WT | C1 | WT | C1 | WT | C1 | WT | C1 | |

| nmol mg−1 dry wt | ||||||||||||

| Amino Acid/NH4+ | ||||||||||||

| Control | 112 | 171 | ||||||||||

| Water stress | 102.9 | 212.2 | 54.4 | 51.5 | 40.2 | 39.2 | 69.8 | 49.0 | – | – | ||

| Rehydration | 42.1 | 62.1 | 134.5 | 138.3 | 243 | 2.0 | ||||||

| Asp | ||||||||||||

| Control | 12.6 | 13.5 | ||||||||||

| Water stress | 10.3 | 14.5 | 8.31 | 5.23 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 5.6 | 4.2 | – | – | ||

| Rehydration | 4.9 | 4.7 | 13.6 | 11.0 | 16.9 | 12.7 | ||||||

| Ser | ||||||||||||

| Control | 10.1 | 9.9 | ||||||||||

| Water stress | 5.7 | 7.4 | 7.0 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 3.3 | – | |||

| Rehydration | 3.5 | 3.5 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 12.3 | 9.8 | ||||||

| Asn | ||||||||||||

| Control | 2.0 | 3.3 | ||||||||||

| Water stress | 2.1 | 4.8 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.4 | – | – | ||

| Rehydration | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 5.0 | 5.1 | ||||||

| Glu | ||||||||||||

| Control | 24.0 | 24.9 | ||||||||||

| Water stress | 25.5 | 31.3 | 11.6 | 15.8 | 14.0 | 14.5 | 17.2 | 16.9 | – | – | ||

| Rehydration | 15.5 | 21.0 | 25.6 | 25.8 | 43 | 37 | ||||||

| Gln | ||||||||||||

| Control | 29.1 | 82.5 | ||||||||||

| Water stress | 22.6 | 104.9 | 6.1 | 9.1 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 10.2 | 4.5 | – | – | ||

| Rehydration | 2.5 | 5.5 | 45.3 | 49.4 | 91 | 115 | ||||||

| Pro | ||||||||||||

| Control | 21.4 | 15.3 | ||||||||||

| Water stress | 19.7 | 22.6 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 12.0 | 3.4 | – | – | ||

| Rehydration | 2.2 | 10.0 | 23.4 | 22.2 | 35 | 36 | ||||||

| Gly | ||||||||||||

| Control | 3.1 | 4.9 | ||||||||||

| Water stress | 1.9 | 5.2 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 | – | – | ||

| Rehydration | 0.9 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 5.6 | 4.8 | ||||||

| Ala | ||||||||||||

| Control | 5.6 | 4.9 | ||||||||||

| Water stress | 4.1 | 5.2 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 2.8 | – | – | ||

| Rehydration | 3.1 | 2.7 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 6.3 | 5.7 | ||||||

| NH4+ | ||||||||||||

| Control | 14.9 | 15.6 | ||||||||||

| Water stress | 7.4 | 14.4 | 9.7 | 6.8 | 3.9 | 7.0 | 9.9 | 11.4 | – | – | ||

| Rehydration | 2.6 | 11.9 | 16.5 | 13.4 | 17.1 | 15.3 | ||||||

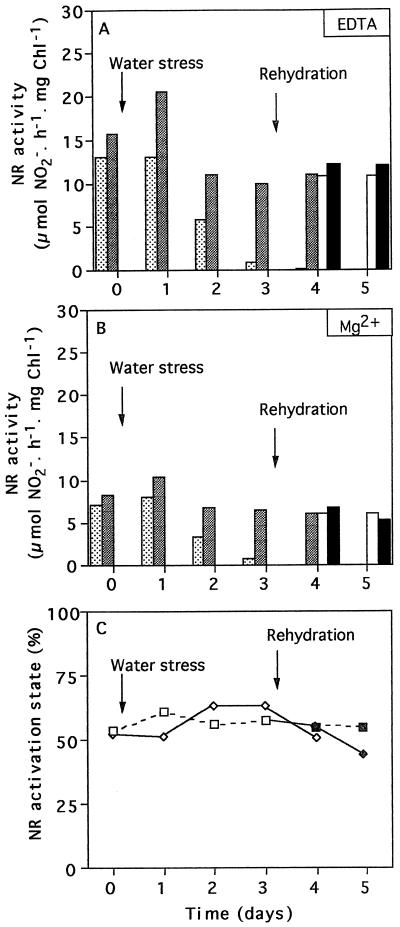

Foliar NR Activity, NR Activation State, and NR mRNA Content

Maximal extractable NR activity was higher in the leaves of the 35S-NR transformants than in those of the untransformed controls in well-watered conditions (Fig. 5A). Foliar NR activity decreased from d 2 of water stress in both lines, but the decrease was more pronounced in the leaves of the untransformed controls than in those of the 35S-NR transformants. After 4 d of water deficit no NR activity could be detected in the leaves of the untransformed plants, whereas more than 50% of the original NR activity remained in the leaves of the transformed line (Fig. 5, A and B). Rehydration induced an increase in NR activity in the untransformed line; NR activity approached control values within 2 d of restoring the water supply, and there was no longer any difference in NR activity between the two lines. The NR activation state was not modified by the water stress (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

The effect of water deprivation on maximal extractable NR activity (A), on NR activity extracted and assayed in the presence of Mg2+ (B), and on the NR activation state (C). A and B, Leaves from untransformed N. plumbaginifolia (stippled bars) and in 35S-NR transformants (shaded bars) were compared. The effects of rehydration after 3 d of water stress on untransformed N. plumbaginifolia (white bars) and in 35S-NR transformants (black bars) were measured on d 4. C, Untransformed controls (□) and 35S-NR transformants (⋄) were subjected to water stress for 3 d and then water was restored for a further 2 d (▪,♦). Chl, Chlorophyll.

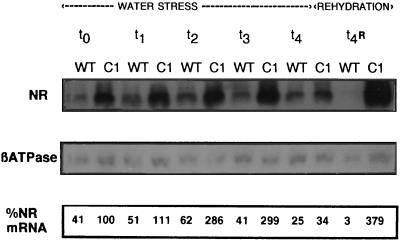

Twice the amount of NR mRNA (expressed as a percentage of β-ATPase) was present in the leaves of the 35S-NR line compared with those of the untransformed controls (Fig. 6). The difference in NR mRNA content was most marked after 3 d of water deficit, when NR mRNA abundance in the transformed line was about 7 times that of the untransformed controls (Fig. 6). This difference was due entirely to an increase in NR mRNA in the transformed line. Steady-state transcript abundance was not changed in the untransformed controls at d 3, whereas NR activity had decreased in the leaves of the untransformed controls (Figs. 5A and 6). This suggests that the stability of the NR protein, but not NR mRNA, was affected by water stress at this time. On d 4 of water stress, NR mRNA decreased suddenly in the 35S-NR transformants, decreasing to values similar to those found in the untransformed controls grown in similar conditions (Fig. 6). Rehydration did not restore NR mRNA abundance in the untransformed controls, which decreased even further, whereas in the 35S-NR leaves recovery was rapid. In the untransformed controls NR mRNA abundance had not recovered after 24 h of rehydration (Fig. 6), whereas it was nearly four times that measured at the beginning of the experiment in the 35S-NR transformants.

Figure 6.

The effect of water deprivation on NR mRNA accumulation in leaves of untransformed N. plumbaginifolia (WT) and 35S-NR transformants (C1) expressed as a percentage of βATPase mRNA. Plants were deprived of water immediately after the first measurement on day t0. mRNA abundance was then measured at the same point in the photoperiod on consecutive days of water stress (t1, t2, t3, and t4) and after 1 d of rehydration following 3 d of water deprivation (t4R).

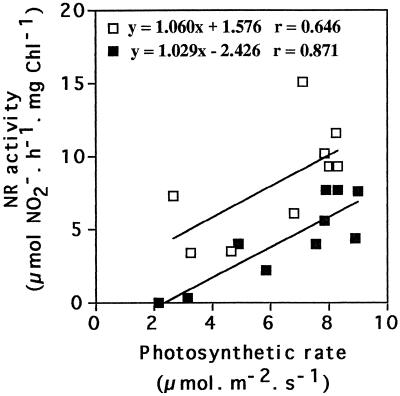

Relationships between Maximal Extractable NR Activity and Photosynthetic Activity

A correlation between maximal extractable NR activity and net photosynthesis was observed in both lines. Decreases in photosynthetic activity following water deprivation were accompanied by comparable decreases in NR activity (Fig. 7). NR activity was always higher in the leaves of the 35S-NR line than in untransformed controls at similar photosynthetic activities (Fig. 7). When photosynthesis was maximally inhibited as a result of water deprivation, NR activity was undetectable in the untransformed plants (Fig. 7). In the 35S-NR transformants, however, NR activity was always detectable even in severe water stress. Therefore, the relationship between maximal extractable NR activity and CO2 assimilation rate was shifted in the transformed plants compared with untransformed controls, but the two parameters always decreased in parallel in both lines of plants (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

The relationship between maximal extractable NR activity and ambient photosynthesis in leaves of untransformed (▪) N. plumbaginifolia and of 35S-NR (□) transformants during water stress. Chl, Chlorophyll.

DISCUSSION

Drought induced a rapid decrease in NR activity in untransformed tobacco leaves similar to that observed in maize (Foyer et al., 1998) and in other species (Plaut, 1974; Heuer et al., 1979). During the first 3 d of drought this was caused by a decrease in NR protein. On d 4 of water deprivation NR transcripts also decreased in both lines. Drought-induced changes in NR gene expression caused by differences in foliar NO3− and sugar content should only largely affect the native NR promoter, but drought-induced effects on the expression of the 35S promoter are also possible. In the present study differences between the 35S-NR transformants and the untransformed lines were evident in NR transcripts. NR mRNA abundance greatly increased in the 35S transformants over the first 3 d of drought but was stable in the leaves of untransformed controls during this period.

Only at an advanced stage of dehydration (4 d) was NR mRNA decreased in both lines. In the 35S-NR line NR mRNA abundance was restored within 24 h of rehydration but in the transformed controls it did not recover during this period. Therefore, 35S-NR expression appears to be less inhibited by drought than expression of the native NR promoter. Figure 6 clearly demonstrates that NR transcript abundance is increased as a result of water deficit in the transformants. NR mRNA stability may be affected by water stress. Effects on stability would be comparable if the concentrations of metabolic factors affecting stability were similar in both lines. The decrease in NR mRNA abundance after 4 d of drought might be a response to changes in metabolite concentrations. NO3− concentration affects NR mRNA stability and NR gene transcription (Galangau et al., 1988). Gln may exert a negative influence on NR mRNA stability, since NR transcript abundance increased following drought as the foliar Gln pool decreased.

Changes in NR activity were observed in both lines during water stress, but NR activity persisted in the leaves of transformants for much longer than in the untransformed control leaves. Water stress induces proteases that increase protein turnover (Ingram and Bartels, 1996). Cys proteases were induced within 10 h of the onset of water stress in A. thaliana (Koizumi et al., 1993). In addition, a thiol proteinase has been identified as an NR-inactivating factor in barley leaves (Hamano et al., 1984). Proteases may be induced by drought in more or less the same manner in both tobacco lines used in this study. The induction of an NR-specific protease may explain the observed decrease of NR activity, since loss of NR protein occurred in the absence of changes in NR mRNA abundance.

In the 35S-NR line, NR activity was always higher than that of the untransformed controls and remained present even when the photosynthetic activity was decreased to a minimum value. Relatively high rates of transcription or deregulation of transcription in the 35S-NR line could compensate for losses in NR protein incurred as a result of increased protease activity. The high level of NR activity found in the leaves of the 35S-NR line during drought could also result from the more or less ubiquitous expression of the 35S promoter, which allows expression of the NR gene in all plant tissues, unlike the native NR promoter, which is expressed only in leaf mesophyll cells. Consequently, if proteolytic degradation of the NR protein is tissue specific, it would be less efficient in the 35S-NR line than in the untransformed controls.

Phosphorylation of the NR protein has been shown to occur rapidly (within hours) as a result of water deficit (Kaiser and Förster, 1989; Brewitz et al., 1996). In addition, the phosphorylated form of the NR protein has been suggested to be less stable than the unphosphorylated protein and, therefore, perhaps more sensitive to proteolytic degradation (Lejay et al., 1997). In the present study only the longer-term effects of water stress were studied. NR activation state was not modified as a result of drought (Fig. 5), suggesting that phosphorylation of NR protein may be an early but transitory response to water stress. The only report of long-term increases in the phosphorylation state of NR during drought concerns maize, a C4 plant (Foyer et al., 1998). Furthermore, water-deficit-induced changes in phosphorylation state may differ between species and, therefore, would be different in tobacco compared with spinach (Kaiser and Förster, 1989), tomato (Brewitz et al., 1996), or maize (Foyer et al., 1998), in which this type of regulation has been observed.

The results presented here suggest that water stress initially causes a decrease in the stability of the NR protein. The effects of this change were observed much earlier in the untransformed controls than in the 35S-NR transformants. This might be interpreted as a decrease in the sensitivity of the 35S transformants to drought-induced effects on N metabolism. The total foliar amino acid pool was higher in the 35S-NR leaves at the beginning of the experiment and remained higher on the 1st d of drought. This suggests that more efficient N assimilation can occur in the 35S-NR transformants than in the untransformed controls during short-term (24-h) water deficits. As long as NO3− did not limit NR assimilation, the amino acid contents of the leaves of the 35S-NR line did not decrease. Substantial decreases in foliar NO3− have been reported in droughted leaves (Heckathorn and De Lucia, 1994, 1995), whereas total amino acid levels may increase in the advanced stages of drought because of proteolysis (Fukutoku and Yamada, 1984) and perturbations in the translocation of amino acids from shoots to roots (Larsson, 1992).

Primary metabolism must maintain the supply of C skeletons, ATP, and reducing power to drive N assimilation during water stress. In the early states of drought, dehydration causes stomatal closure and CO2 fixation is limited by CO2 availability. Photosynthetic electron transport, mitochondrial respiration, and photorespiration are still active and can even increase at this stage (Krampitz and Fock, 1984). The NADH required for NO3− reduction in leaves can be provided by several different sources, such as oxidation of glyceraldehyde 3-P or substrate oxidation in the tricarboxylic acid cycle or Gly oxidation (Kumar et al., 1988). However, shoot biomass production was comparable in the two lines over the first 5 d of water stress. Similarly, photosynthesis was decreased by water deficits to a comparable degree in both lines. Therefore, constitutive NR expression did not facilitate higher photosynthetic rates in the 35S-NR transformants than in the untransformed controls, as was already observed with varying NO3− supply (Ferrario et al., 1995). However, correlations between maximal extractable NR activity and net photosynthesis were observed in both lines regardless of the foliar NR activity prior to water deprivation.

These findings demonstrate coordinate regulation of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation and NR activity in tobacco leaves. In C4 prairie grasses drought-induced losses in photosynthetic capacity were shown to result largely from decreases in shoot N; recovery of photosynthesis following drought was only possible when shoot N contents were restored (Heckathorn and De Lucia, 1994, 1995; Heckathorn et al., 1997). The present study demonstrates that coordinate control of C and N assimilation can also be observed in tobacco. In this case, the regulatory relationship involves total extractable NR activity and net photosynthesis. Metabolic cross-talk between C and N metabolism involves multiple steps of coordinate control in which many metabolic signals such as NO3−, Gln, Suc, and reductants participate.

The molecular and metabolic basis for the correlations presented in Figure 7 must therefore be highly complex and also indicate that the precise regulatory coordination is perturbed, at least in the short term, by constitutive NR expression. This not only suggests that at least part of the coordinate regulation involves regulation of NR gene transcription in the untransformed plants but also demonstrates that the other mechanisms of NR regulation cannot compensate for the absence of normal transcriptional controls (at least in the short term). Only after 4 d of water stress were NR mRNA levels decreased in both lines. At this point NR activity was still present in the leaves of the transformants. Although other factors such as NO3− availability interact to limit the flux through the pathway of N assimilation, there is no doubt that the transformants are better equipped in terms of available NR protein to rapidly restore N assimilation, when favorable conditions return, than the untransformed controls. No immediate benefit was observed in terms of biomass accumulation in the short term, but under field conditions of fluctuating water availability constitutive NR expression may confer a physiological advantage by providing a preemptive modification, preventing slowly reversible losses in N-assimilation capacity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are indebted to Yvette Roux for assistance with amino acid analyses.

Abbreviations:

- NR

nitrate reductase

- 35S

35S promoter from cauliflower mosaic virus

Footnotes

This work was funded by European Economic Community Biotechnology (contract no. BIO2 CT93 0400) and was a project of the Technical Priority Network D—Nitrogen Utilization and Efficiency.

LITERATURE CITED

- Arnon DI. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidases in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24:1–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker TW, Fock HP. The activity of nitrate reductase and some pool sizes of some amino acids and some sugars in water-stressed maize leaves. Photosynth Res. 1986a;8:267–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00037134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker TW, Fock HP. Effects of water stress on the gas exchange, the activities of some enzymes of carbon and nitrogen metabolism, and on the pool sizes of some organic acids in maize leaves. Photosynth Res. 1986b;8:175–181. doi: 10.1007/BF00035247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyrouty CA, Grigg BC, Norman RJ, Wells BR. Nutrient uptake by rice in response to water management. J Plant Nutr. 1994;8:39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bountry M, Chua NH. A nuclear gene encoding the beta subunit of the mitochondrial ATP synthase in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia. EMBO J. 1985;4:2159–2165. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03910.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewitz E, Larsson CM, Larsson M. Responses of nitrate assimilation and N translocation in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill) to reduced ambient air humidity. J Exp Bot. 1996;47:855–861. [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo DA, Haroon M, Schrader LE, Yougs VL. Rapid colorimetric determination of nitrate in plant tissue by nitration of salicylic acid. Commum Soil Sci Plant Anal. 1975;6:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Champigny M-L, Foyer CH. Nitrate activation of cytosolic protein kinases diverts photosynthetic carbon from sucrose to amino acid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:7–12. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CL, Acedo GN, Christinsin M, Conkling MA. Sucrose mimics the light induction of Arabidopsis nitrate reductase gene transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1861–1864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coïc Y, Lesaint C. Alsace. 1975;23:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario S, Valadier M-H, Foyer CH. Short-term modulation of nitrate reductase activity by exogenous nitrate in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia and Zea mays leaves. Planta. 1996;199:366–371. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario S, Valadier M-H, Morot-Gaudry J-F, Foyer CH. Effects of constitutive expression of nitrate reductase in transgenic Nicotiana plumbaginifolia L. in response to varying nitrogen supply. Planta. 1995;196:288–294. [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Valadier M-H, Migge A, Becker TW. Drought-induced effects on nitrate reductase activity and mRNA and on the coordination of nitrogen and carbon metabolism in maize leaves. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:283–292. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.1.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukutoku Y, Yamada Y. Sources of proline-nitrogen in water-stressed soybean (Glycine max). II. Fate of 15N-labelled protein. Physiol Plant. 1984;61:622–628. [Google Scholar]

- Galangau F, Daniel-Vedele F, Moureaux T, Dorbe MF, Leydecker MT, Caboche M. Expression of leaf nitrate reductase genes from tomato and tobacco in relation to light/dark regimes and nitrate supply. Plant Physiol. 1988;88:383–388. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.2.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtier N, Foyer CH, Murchie E, Alred R, Quick P, Voelker TA, Thepenier C, Lasceve G, Betsche T. Effects of light and atmosphere CO2 enrichment on photosynthetic carbon partitioning and carbon/nitrogen ratios in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) plants over-expressing sucrose phosphate synthase. J Exp Bot. 1995;46:1335–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Glaab J, Kaiser WM. Inactivation of nitrate reductase is a two-step mechanism involving NR-protein, phosphorylation and subsequent ‘binding’ of an inhibitor protein. Planta. 1995;195:514–518. [Google Scholar]

- Hamano T, Oji Y, Okamoto S, Mitsuhashi Y, Matsuki Y. Purification and characterisation of thiol proteinase as a nitrate reductase-inactivating factor from leaves of Hordeum distichum L. Plant Cell Physiol. 1984;25:419–427. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn SA, De Lucia EH. Drought-induced nitrogen retranslocation in perennial C4 grasses of tallgrass prairie. Ecology. 1994;75:1877–1886. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn SA, De Lucia EH. Ammonia volatilization during drought in perennial C4 grasses of tallgrass prairie. Oecologia. 1995;101:361–365. doi: 10.1007/BF00328823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn SA, De Lucia EH, Zielinski RE. The contribution of drought-related decreases in foliar nitrogen concentration to decreases in photosynthetic capacity during and after drought in prairie grasses. Physiol Plant. 1997;101:173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Heuer B, Plaut Z, Federman E. Nitrate and nitrite reduction in wheat leaves as affected by different types of water stress. Physiol Plant. 1979;46:318–323. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram J, Bartels I. The molecular basis of dehydration tolerance in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:377–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser WM, Förster J. Low CO2 prevents nitrate reduction in leaves. Plant Physiol. 1989;91:970–974. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.3.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi M, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Tsuji H, Shinozaki K. Structure and expression of two genes that encode distinct drought-inducible cysteine proteinases in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene. 1993;129:175–182. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krampitz MJ, Fock HP. 14CO2 assimilation and carbon flux in the Calvin cycle and the glycolate pathway in water-stressed sunflower and bean leaves. Photosynthetica. 1984;18:329–337. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar PA, Nair TVT, Abrol YP. Glycine supports in vivo reduction of nitrate in barley leaves. Plant Physiol. 1988;88:1486–1488. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.4.1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson M. Translocation of nitrogen in osmotically stressed wheat seedlings. Plant Cell Environ. 1992;15:447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson M, Larsson CM, Whitford PN, Clarkson DT. Influence of osmotic stress on nitrate reductase activity in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and the role of abscisic acid. J Exp Bot. 1989;41:1265–1271. [Google Scholar]

- Lejay L, Quilleré I, Roux Y, Tillard P, Cliquet J-B, Meyer C, Morot-Gaudry J-F, Gojon A. Abolition of posttranscriptional regulation of nitrate reductase partially prevents the decrease in leaf NO3− reduction when photosynthesis is inhibited by CO2 deprivation, but not in darkness. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:623–630. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.2.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKintosh C, Douglas P, Lillo C. Identification of protein that inhibits the phosphorylation form of nitrate reductase from spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves. Plant Physiol. 1995;84:58–60. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.2.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Naussaume L, Vincentz M, Meyer C, Boutin JP, Caboche M. Post-transcriptional regulation of nitrate reductase by light is abolished by an N-terminal deletion. Plant Cell. 1995;7:611–621. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.5.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaut Z. Nitrate reductase activity of wheat seedlings during exposure to and recovery from water stress and salinity. Physiol Plant. 1974;30:212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Pugnaire FI, Chapin FS., III Environmental and physiological factors governing nutrient resorption efficiency in barley. Oecologia. 1992;90:120–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00317817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilleré I, Duffosse C, Roux Y, Foyer CH, Caboche M, Morot-Gaudry JF. The effects of deregulation of NR gene expression on growth and nitrogen metabolism of Nicotiana plumbaginifolia plants. J Exp Bot. 1994;45:1205–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Rochat C, Boutin J-P. Carbohydrates and nitrogenous compounds changes in the hull and in the seed during the pod development of pea. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1989;27:881–887. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H. A modified ninhydrin colorimetric analysis for amino acids. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1957;64:10–15. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(57)90241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner DL, Boyer JS. Nitrate reductase activity in maize (Zea mays L.leaves. I. Regulation by nitrate flux. Plant Physiol. 1976;58:499–504. doi: 10.1104/pp.58.4.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talouizite A, Champigny ML. Response of wheat seedlings to short-term drought with particular respect to nitrate utilization. Plant Cell Environ. 1988;11:149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Urao T, Katagiri T, Mizoguchi T, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Hayashida N, Shinozaki K. Two genes that encode Ca2+-dependent protein kinases are induced by drought and high-salt stresses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;244:331–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00286684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaucheret H, Vincentz M, Kronenberger J, Caboche M, Rouze P. Molecular cloning and characterisation of the two homologous genes coding for nitrate reductase in tobacco. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;216:10–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00332224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verwoerd TC, Dekker BMM, Hoekema A. A small-scale procedure for the rapid isolation of plant RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2362. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.6.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincentz M, Caboche M. Constitutive expression of nitrate reductase allows normal growth. EMBO J. 1991;10:1027–1035. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincentz M, Moureaux T, Leydecker MT, Vaucheret H, Caboche M. Regulation of nitrate and nitrite reductase expression in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia leaves by nitrogen and carbon metabolites. Plant J. 1993;3:315–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1993.tb00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]