Abstract

Blood stage malaria parasites target a ’secretome’ of hundreds of proteins including virulence determinants containing a host (cell) targeting (HT) signal, to human erythrocytes. Recent studies reveal that the export mechanism is due to the HT signal binding to the lipid phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI(3)P) in the parasite endoplasmic reticulum (ER). An aspartic protease plasmepsin V which cleaves a specialized form of the HT signal was previously thought to be the export mechanism, but is now recognized as a dedicated peptidase that cleaves the signal anchor subsequent to PI(3)P binding. We discuss a model of PI(3)P-dependent targeting and PI(3)P biology of a major human pathogen.

Keywords: malaria, phosphoinositides, host-targeting, pathogenic secretion, export, blood cells, endoplasmic reticulum

Pathology of malaria

Despite concerted efforts to control malaria, the disease continues to extract a major toll on human health (http://www.who.int/malaria/world_malaria_report_2010). The most virulent causative species to infect humans is the protozoan, Plasmodium falciparum. Plasmodium vivax, the second major causative agent of malaria, adds considerable disease burden [1] and Plasmodium knowlesi is an emerging human pathogen that also has an animal reservoir [2]. In these and other malarial species, blood stage parasites that infect erythrocytes (and reticulocytes in the case of P. vivax) cause the symptoms and pathologies associated with acute infection as well as severe disease [3]. If the extracellular merozoite stage does not invade host erythrocytes within minutes, it will die in circulation. Thus, successful infection of the erythrocyte and subsequent development are critical to parasite survival in blood. The erythrocyte lacks a nucleus, so unlike many other pathogens, blood stage malaria parasites do not take over transcriptional control of the host cell. Rather they alter transport and antigenic functions to obtain nutrients as well as avoid the host immune system, by exporting effector proteins to the erythrocyte cytoplasm and membrane. This occurs early in intraerythrocytic development and the processes by which effector proteins are exported provide fundamental mechanisms that can be targets to control both infection and disease. Our most recent advances suggest that binding phosphoinositide PI(3)P in the lumen of the parasite’s ER is a critical host targeting step that precedes signal anchor cleavage in the ER [4].

Malaria parasites remodel red cells by exporting hundreds of proteins including virulence determinants to human erythrocytes

The most obvious manifestations of host remodeling by P. falciparum are (i) knobs on the infected erythrocyte surface (ii) Maurer’s clefts and (iii) a tubovesicular network (TVN) in the infected-erythrocyte cytoplasm (Box 1). Knobs are surface membrane protrusions that concentrate adhesins also called variant antigens (or var), that bind endothelial receptors This leads to occlusion of blood vessels and the deadly pathology of cerebral malaria [5]. Maurer’s clefts are cisternal membranes in the periphery of the infected erythrocyte and implicated in export of parasite proteins to the knobs and the infected erythrocyte membrane [6]. The TVN is an interconnected network that extends from the parasite to the erythrocyte membrane, first described for nutrient uptake [7]. Additional populations of large and small intraerythrocytic vesicles have also been described. The type and the extent of modification induced by the parasite can vary between malarial species, but nonetheless all Plasmodium spp. remodel their erythrocytic host cell.

Box 1. Protein trafficking in P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes.

Infection of human red blood cells by protozoan parasite Plasmodium falciparum results in the most severe form of human malaria. The intraerythrocytic parasite (blue) resides within a membranous sac called the parasitophorous vacuole (PV) and develops complex tubovesicular network (TVN) and Maurer’s clefts (bright green crescent). Membranous protrusions, also called knobs, form at the infected-erythrocyte surface to concentrate variant antigens (var also called PfEMP1 proteins, brown squares) to bind endothelial receptors (yellow) This leads to occlusion of blood vessels and is associated with cerebral malaria. Maurer’s clefts are membranous cisternae at the periphery of the infected erythrocyte and implicated in export of parasite proteins to knobs and the infected erythrocyte membrane. The TVN is an interconnected network that extends from the parasite to the erythrocyte membrane and is involved in nutrient uptake. Approximately 400 secretory proteins (brown and red squares) that contain a host targeting motif are predicted to be exported across the PV membrane to the red cell (blue arrow) to aid in host red cell modification. Secretory proteins lacking the HT motif are released into the PV (grey arrow). Within the parasite, we show membrane domains emerging from the endoplasmic reticulum enriched for PI(3)P (beige circles) in their lumen and associated with secretome proteins. Shown in the expanded inset is a single optical section from a live infected-erythrocyte indicating regions of PI(3)P (beige) in the parasite ER (grey), rendered through an artistic coloration filter.

As many as 400 P. falciparum proteins are predicted to be exported to the erythrocyte, encoded by 8% of the parasite’s genome. These numbers, derived from several bioinformatics predictions, may overestimate because many of the proteins remain hypothetical [8]. Only the most restricted predictive algorithms are found to have a positive prediction rate of 60–70% [9]. This estimate is based on testing eleven putative, host targeted genes that were conserved and syntenic across the genus Plasmodium, but larger numbers of genes need to be assessed, to comprehensively sample the large predictive set of P. falciparum. Nonetheless, many parasite proteins that belong to the variant antigen families like VAR, RIFIN and STEVOR (constituting 250 of the 400 putative effectors) are clearly exported [10, 11]. A recently validated, major exported protein induces a nutrient channel in the infected erythrocyte membrane [12]. There are other members of protein families as well as individual proteins that have been functionally validated for export, whose identities and molecular properties have been summarized elsewhere and will not be discussed. A current map of exported proteins and their likely host destinations are summarized in Box 1.

Mechanisms of malaria parasite protein export to the erythrocyte

The intra-erythrocytic parasite resides and proliferates within a parasitophorous vacuolar membrane (PVM). Thus to access the erythrocyte, parasites have to export proteins past the parasite plasma membrane (PPM) as well as the PVM. As in other eukaryotes, the presence of an ER-type signal sequence is sufficient for secretion at the PPM into the parasitophorous vacuole (PV). Proteins exported to the erythrocyte additionally contain a downstream host cell (HT) targeting signal (also called Plasmodium export element, PEXEL) with a five amino acid motif R/KxLxE/D/Q [10, 11, 13]. Although this motif was identified eight years ago, as the first host targeting signal for a eukaryotic pathogen, its mechanism of action has remained elusive. PEXEL negative proteins (or PNEPs) are also exported to the erythrocyte [14, 15]. These include proteins like P. falciparum Skeleton binding protein 1 (PfSBP1) that are major component proteins of the Maurer’s clefts. Charged peptides are thought to play a role in the export of these proteins, but a clear underlying consensus targeting signal has not yet emerged.

Gehde et al. [16] have reported that despite the presence of an HT motif, proteins with a tightly folded structure are not exported to the host erythrocyte. This is consistent with a model of motif-dependent translocation across the PVM that requires unfolding of the protein cargo. In the context of this model, cleavage of the HT motif within the parasite, first reported by Chang et al.[17], was mystifying. Yet, data emerged that mutation in the three conserved positions of the motif results in ER/PV location of reporters [18]. An ER-retained reporter was cleaved with the same efficiency in absence of ER retention, providing definitive evidence that cleavage occurred in the ER [19]. HT signal cleavage by an aspartic protease plasmepsin V, based largely on in vitro studies, was proposed to release proteins from the ER membrane and target protein to the erythrocyte [20, 21]. Together these studies suggested that contrary to expectation, the HT motif did not translocate protein across the PVM, but must act by targeting from the ER.

An ER resident protease, plasmepsin V, was proposed to cleave the RxLxE/D/Q form of the HT signal and thus target the protein to the host erythrocyte [20, 21]. Although its function as a peptidase is undisputed, the major caveats to invoking plasmepsin V as the mechanism of targeting are as follows. First, the var genes that encode for variant adhesins, contain an HT motif containing K (in place of the R). Studies on the substrate specificity of plasmepsin V reveal that it does not cleave at KxL motifs, even while it efficiently recognizes RxL motifs in the same peptidic regions [20, 21]. Additionally, the bulk of the evidence that cleavage by plasmepsin V targeted export came from the data with one reporter construct [20]. Here, when the HT signal was re-designed to be cleaved by signal peptidase rather than plasmepsin V, the associated reporter failed to be exported to the host erythrocyte. However, utilization of a second, signal peptidase cleavage site generated reporters that contained charged sequences downstream of the cleaved HT motif, and enabled protein export to the erythrocyte [4], demonstrating even in HT motif containing proteins, export may occur by HT-independent mechanisms. By contrast, PI(3)P binding is conserved across both R and K forms of the HT signal (as well as the related HT signal of Phytophthora infestans) and thus accounts for export of all major members of the secretome (Figure 1). This coupled with the unexpected finding of PI(3)P as well as uncleaved precursor forms of secretome proteins in the parasite interact with PI(3)P in the parasite’s ER (Figure 2), suggested involvement of phosphoinositides early in the export process.

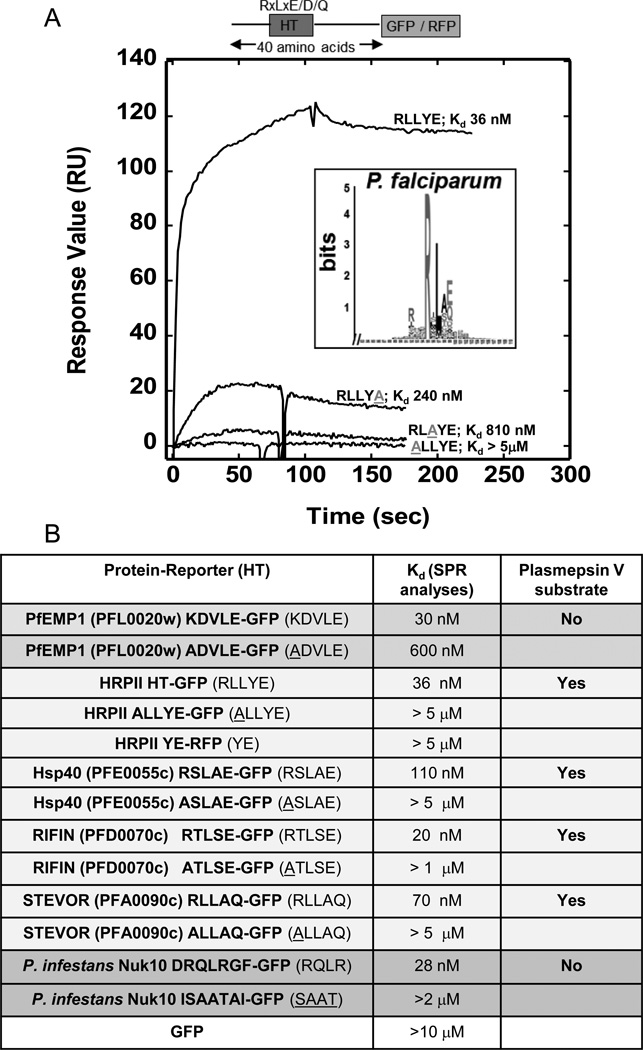

Figure 1.

Lipid binding properties of HT signals. (a) Logo and Kd values for each recombinant form of PfHRPII reveals PI(3)P binding with nanomolar affinity and amino acid specificities displayed by HT-mediated export [4]. Sequence logo is derived from HT signal of P. falciparum secretory proteins [10]. Amino acids are represented by one-letter abbreviations. Height of amino acids indicates their frequency at that position. SPR analysis demonstrates quantitative lipid binding of HT/RLLYE-GFP, ALLYE-GFP, RLAYE-GFP, and RLLYA-GFP for PI(3)P containing vesicles. 1 M of each construct was injected over a POPC:POPE:PI(3)P (75:20:5) surface using POPC:POPE (80:20) as a control. The control response was subtracted from each active surface to yield the displayed sensorgrams. Adapted from [4]. (b) A summary of PI(3)P binding properties and plasmepsin V susceptibility of HT motifs of P. falciparum PfEMP1, PfHRPII, PfHsp40, RIFIN, STEVOR as well as P. infestans Nuk10. Adapted from [4], [20], [21].

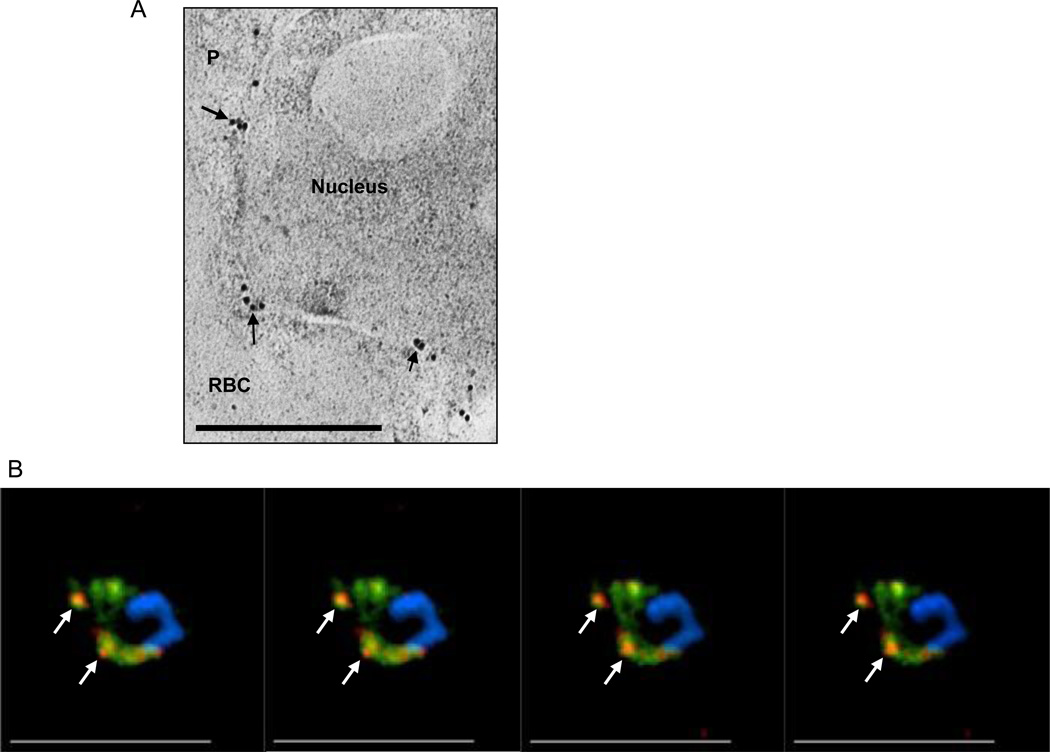

Figure 2.

PI(3)P is detected in P. falciparum endoplasmic reticulum. (a) Immuno-electronmicroscopy showing localization of secretory EEA1WT-mCherry in reticular perinuclear membranes characteristic of the ER. Thin sections, probed with anti-mCherry and secondary antibody gold conjugates (10 nm) show label concentrated in membrane regions emerging from reticular membrane apposed to the nucleus (arrows), consistent with localization in the ER. Scale bar, 0.5 µm. [4]. (b) Successive single optical z-sections of a precursor ER form of a secretome protein PfHRPII (pPfHRPII; green) prior to cleavage by plasmepsin V and its colocalization with PI(3)P regions (red). Subsets of prominent areas of colocalization are indicated by arrows.

Abbreviations: RBC, red blood cell; P, parasite.

PI(3)P in P. falciparum

PI(3)P is known to be a cytoplasmic lipid in cells, but to bind the HT signal on newly synthesized parasite effectors exported to the erythrocyte, it needs to be present in the lumen of parasite’s secretory pathway and act prior to HT signal cleavage in the ER. Secretory expression of PI(3)P binding domains of proteins such as the FYVE domain of early endosomal antigen-1 (EEA1) and PX domain of p40-phox [22], tagged with monomeric Cherry (mCherry) and their localization to the ER, proved that PI(3)P is present in the lumen of the ER. The precise mechanism by which cytoplasmic PI(3)P is recruited into the ER lumen is unknown. However, we have considered here the parasite’s cellular sources of PI(3)P and how they may influence PI(3)P dynamics on the cytoplasmic face as well as in the ER lumen.

PI(3)P is a phosphoinositide, which as a group are membrane lipids produced by phosphorylation of the hydroxyl groups of phosphatidylinositol (PI), an important cellular phospholipid. Although PI is found in bacteria, phosphorylated PIs are restricted to eukaryotes and their cellular levels are regulated through lipid kinases and phosphatases. Phosphoinositides participate in diverse cellular processes in eukaryotic cells, with well elucidated roles in trafficking and signal transduction. They show organelle-specific enrichment and may function as address tags. Hence in mammalian cells, the major cellular species, PI(4,5)P2 is found at the plasma membrane. In contrast, less abundant species like PI(3,5)P2 concentrates in late endosomes, PI(4)P, in the Golgi and PI(3)P, on early endosomes [23].

PI(3)P plays a critical role in trafficking in mammalian cells. For instance, the FYVE domain of EEA1 binds PI(3)P as well as the small GTPase Rab5 to regulate early steps of constitutive endocytosis [24]. PI(3)P is also implicated in endosome to Golgi transport and in autophagy [23]. Uninfected erythrocytes (which lack endosomes) do not contain PI(3)P, rather their major lipid species are PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P. However, infected erythrocytes produce a large amount of PI(3)P, estimated to be over a quarter of the total cellular phosphoinositides. Infected erythrocytes also make PI(4)P and additional polyphoinositides PI(3,4)P2, PI(3,4,5)P3, PI(4,5)P2 with the last representing ~70% of total phosphoinositides [25]. However this review will focus on PI(3)P, because of its unexpected targeting of parasite virulence proteins from within the parasite’s ER to the host erythrocyte.

PI(3)P has been shown to be associated with the cytosolic face of malarial parasite’s food vacuole and apicoplast [25]. Both of these organelles are derived from the parasite’s endocytic pathways (although neither can be considered an early endosome). Endosomes/phagosomes that ingest hemoglobin from the erythrocyte fuse with and deliver their contents to the food vacuole, which is the major digestive organelle ([25]; and functions in lieu of lysosomes). The apicoplast is a residual plastid and arose by a secondary endosymbiotic event [26], and thus its outer membranes are derived from the parasite endosomal membrane system. The detection of PI(3)P in association with the apicoplast and food vacuole was achieved by expressing fluorescently tagged PI(3)P binding proteins in the parasites cytoplasm. Under these conditions, parasites also accumulate PI(3)P-enriched vesicles in association with each organelle, whose origin is unclear. Similarly, in a related apicomplexan T. gondii, that lacks the food vacuole but contain an apicoplast, trans expression of PI(3)P-binding proteins revealed PI(3)P in association with the apicoplast and aberrantly attached vesicles. These vesicles were shown to contain outer membrane proteins of the apicoplast [27]. One possibility is that they contain newly synthesized protein from the ER and thus intermediates in biosynthetic transport. An alternative explanation might be that PI(3)P binding proteins induce vesiculation from the outer membranes of the apicoplast. Regardless of the origin of the aberrant vesicles, it is clear that PI(3)P is highly enriched in the cytosolic face of food vacuole and apicoplast membranes (Figure 3). In contrast in the parasite’s ER, PI(3)P is in the lumen, raising question about whether there are two forms of PI3 kinases (PI3K) that synthesize PI(3)P in cytoplasmic and secretory orientation, respectively.

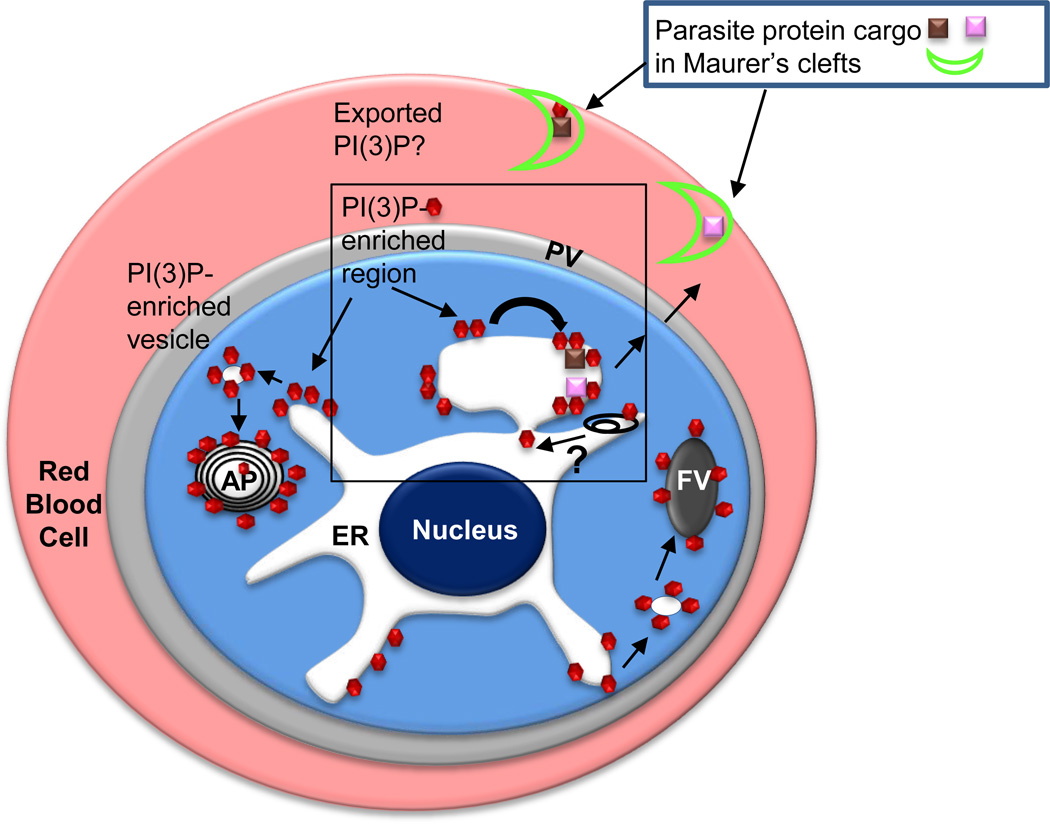

Figure 3.

Secretory and cytoplasmic distribution of PI(3)P in P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Since P. falciparum encodes for a single PI3 kinase, PI(3)P (red hexagons) is expected to be synthesized on the cytoplasmic face of membranes. PI(3)P is reported to be prominently associated with the cytoplasmic face of the apicoplast and the food vacuole. PI(3)P is reported to be essential for hemoglobin uptake from the red cell into the parasite food vacuole (FV) as well as apicoplast (AP) biogenesis [25]. As highlighted in Box 1, PI(3)P is also detected in the lumen of the ER, suggesting it undergoes trans bilayer ‘flip-flop’ from the cytoplasmic face (black curved arrow) either through the action of a ‘flippase’ or possibly internalization of PI(3)P bound by the HT motif as the nascent peptide translocates across the ER membrane. Autophagy (represented by black endomembranes) may also provide a route of uptake of cytoplasmic PI(3)P but whether this releases PI(3)P with correct topology in the ER lumen is unknown (depicted by a question mark). Proteins (pink and brown squares) bound to PI(3)P through an HT motif are exported Maurer’s clefts (bright green crescent) in the host erythrocyte. If the HT signal is not cleaved, PI(3)P may be exported to the host erythrocyte, but for the vast majority of secretome proteins, PI(3)P is not exported to the host erythrocyte.

A single, P. falciparum PI3K synthesizes PI(3)P in blood stage infection

Although there are as many as three PI3K in eukaryotes, Plasmodium (and most unicellular organisms) has one gene, a type III PI3K that is orthologous to mammalian vps34 [28]. The active site between parasite and mammalian enzymes is conserved, but the P. falciparum enzyme appears to be larger and has distinctive repeats. Type III PI3K typically phosphorylate the 3′ OH of phosphatidylinositol to produce PI(3)P. However in addition to making PI(3)P in vitro, the P. falciparum enzyme (PfPI3K) can also utilize PI(4)P and PI(4,5)P2 to produce PI(3,4)P2 and PI (3,4,5)P3 respectively [28, 25].

PfPI3K has been localized to the food vacuole, additional vesicles and the PPM. It is also reported to be exported to the erythrocyte [28]. Its inhibition by Wortmannin and LY294002 results in accumulation of hemoglobin-laden vesicles in the parasite, suggesting a disruption of food vacuole biogenesis. The function of the exported form of the PfPI3K is unclear. Yet export has been detected by both immunolocalization and cell fractionation studies. Further there are polymorphisms in the enzyme, suggesting it may be ‘seen’ by the immune system which may occur when the PfPI3K is exported to the erythrocyte membrane. However, it is difficult to explain how the same protein can be targeted to different destinations within the parasite as well as exported to the host cell. It is possible that isoforms exist, but have not yet been detected. PfPI3K does not contain an HT motif and thus its export to the erythrocyte is likely independent of binding to PI(3)P in the ER. A model has been proposed where the exported enzyme is thought to regulate hemoglobin uptake and trafficking presumably due to synthesis of PI(3)P in the erythrocyte [28], but direct evidence for this extra-parasite synthesis is not yet available.

PfPI3K appears active and constitutively expressed throughout blood stage infection, but there may be elevation in later rophozoite and schizont stages linked to parasite replication. Notably the maximal accumulation of PI(3)P is detected in the trophozoite and/or schizont stages of intraerythrocytic development. The food vacuole and apicoplast develop at these stages. In contrast, to date our analysis of PI(3)P in ER and its action in host targeting have been restricted largely to ‘early, intracellular, ring stage’, when protein export to the erythrocyte is initiated and most active. Secretory PI(3)P in ring stages maybe brought in during invasion of merozoites or result from new synthesis early in intra-erythrocytic development. PI(3)P levels could also be regulated by phosphatases, but lipid phosphatases, have not yet been described in Plasmodium. It remains unknown what fraction of total PI(3)P in the parasite is in the ER and whether blocking type III PfPI3K will influence protein export.

A possible mechanism for concentration of PI(3)P in the ER or the lumen of the apicoplast, could be trans-bilayer import of PI(3)P synthesized on the cytoplasmic face by a ‘flippase’ (Figure 3, Box 1). Although phospholipid flippases have been described, none are known to be specific for phosphoinositides which present bulky, polar head groups that are not thermodynamically favored to translocate across the hydrophobic core of a membrane’s lipid bilayer. PI(3)P may become lumenal in multi-endovesicles during autophagy [23]. This is prominent in yeast, but little is known about autophagy in malaria parasites and whether this will deliver PI(3)P in multi-membrane vesicles to the lumen of ER is unknown. In an alternate mechanism, PI(3)P localized on the cytoplasmic face of ER may be internalized into the lumen when it is recognized by the HT motif during protein synthesis. The nanomolar affinity for the HT to PI(3)P may be sufficient to drive this internalization process in a co-translational way. To full distinguish between these complex, yet critical mechanisms, the dynamics and localization of PI(3)P and the PI3K need to be closely investigated during erythrocytic infection.

A new model for host targeting from the parasite’s ER dependent and independent of PI(3)P

PI(3)P association with malarial secretome proteins both in vitro and in vivo, and its requirement in export of proteins via the related P. infestans signal that is not cleaved by plasmepsin V [29],[4], support a model for PI(3)P dependent exit from the ER (Figure 4). In this model, cleavage of the R form of the HT signal by plasmepsin V is proposed to be restricted to an emerging vesicle to retain host-targeted cargo. However, highly charged sequences downstream of the HT signal can also export protein, and these sequences in a cleaved form of the protein (contained in the PfHRPII YE-RFP ) do not have detectable PI(3)P affinity (Figure 1b). Nonetheless they are likely to act within the PI(3)P-dependent emerging vesicle and may help retain cargo after motif cleavage (Figure 4). Further in the uncleaved motif RLLYE (of PfHRPII), the amino acid E contributes significantly to affinity for PI(3)P (Figure 1a). In earlier studies we have demonstrated that replacement of four amino acids upstream of the PfHRPII HT motif also blocked export [30] suggesting additional, proximal regions are necessary for PI(3)P recognition (Figure 4). This is consistent with the idea that nanomolar phosphoinositide binding is attributed to at least four points of contact, and it is likely that sequences upstream of the HT motif contribute additional cationic residues. It should be noted that the HT signal was originally identified as a highly conserved motif by pattern recognition programs in five functionally equivalent ~40 amino acid, vacuolar translocation sequence (VTS) [31, 10] and is thus likely to function in context of a small domain rather than a linear pentameric sequence.

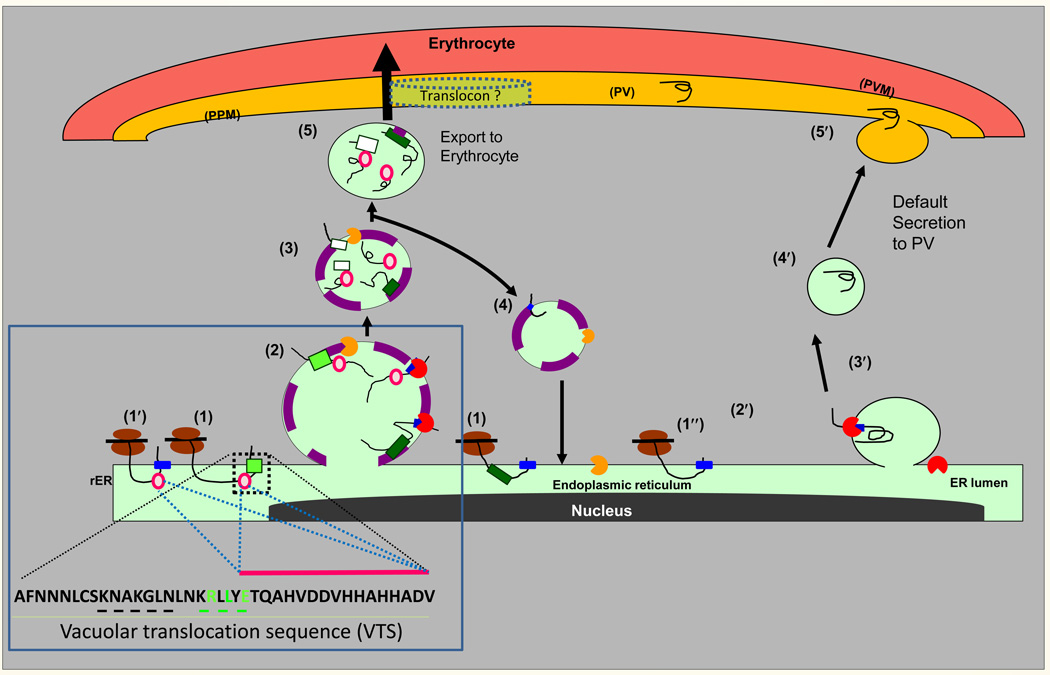

Figure 4.

A model for PI(3)P-dependent and- independent export from the ER of P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Proteins containing the malarial HT-signal (light green square) or the oomycete HT signal (dark green square) are co-translationally inserted via their signal anchor sequences (blue squares) into the ER membrane (step 1). The HT signals recognize the lipid PI(3)P (purple) enriched in regions of the ER (step 2) and may occur co-translationally (not shown). Secretory proteins with a plasmepsin V-refractory HT signal, are cleaved by signal peptidase (red pac-man) but remain associated to PI(3)P. Proteins with the malarial HT signal are cleaved by plasmepsin V (orange pac-man, step 3) which also destroys the PI(3)P binding signal and thus is likely to occur in a newly pinched off vesicle or one whose contents do not freely diffuse with the ER. In addition, highly charged peptide sequences (pink circles) downstream of the HT signal capable of PI(3)P-independent export may also facilitate association with the host targeted pathway despite absence/cleavage of the HT motif (1’ and steps 2 and later). Plasmepsin V and PI(3)P are recycled back to the ER (step 4), while cargo targeted to the erythrocyte moves forward across the parasite plasma membrane (PPM), and PVM (step 5). In default secretion, secretory proteins are co-translationally translocated into the ER (step 1′), the signal sequence (blue square) is cleaved by signal peptidase (red pac-man; steps 2′ and 3′) and protein is delivered through vesicular intermediates to PPM, and released into the PV (steps 4′ and 5′). Steps 1–5 have ~400 predicted cargo proteins exported to the erythrocyte and thus likely the dominant pathway of protein export to the erythrocyte. The role of the Golgi in these pathways is not known. A translocon has been proposed in export to the erythrocyte, but how it recognizes HT signals lost in the ER is unknown. Adapted from [4]. Box 1 describes the vacuolar translocation sequence of PfHRPII and a summary of regions/residues needed for export as well as PI(3)P binding. Shown in green are conserved HT motif residues R, L and E known to contribute to both PI(3)P binding and protein export to the erythrocyte. Substitution of sequences KNAKGLN upstream of the HT motif (underlined in black), also blocked export [30], but have not been tested for PI(3)P binding. Pink circles and pink bar indicating charged amino acids downstream of the HT motif enable export independent of PI(3)P, however, the E residue marked in green contributes to PI(3)P binding in the intact HT motif (see Figure 1). Substitution of HHAHHA sequence in repeat sequences does not block export [30].

Since PI(3)P binding alone (such as by the FYVE domain of EEA1 and PX domain of p40-phox) is insufficient to induce ER exit and host targeting, the HT signals of malarial virulence determinants containing the R/KxLxE/D/Q motif (and the related P. infestans signal), suggest novel mechanisms of PI(3)P interaction. Whether cargo from PI(3)P dependent ER exit traffics through parasite’s Golgi as well as a PVM translocon proposed to mediate export of secretome proteins into the erythrocyte [32, 33], has yet to be investigated. However, cleavage by plasmepsin V results in loss of HT motif by the time proteins transit these compartments. It remains unknown whether PI(3)P remains associated with the K motifs of PfEMP1 exported to the erythrocyte. Nonetheless, since only two members of PfEMP1 are expressed in an infected erythrocyte, the vast majority of PI(3)P dependent export is likely to be modulated by the kinetics of its synthesis, luminal accumulation, secretory exit and recycling in the malaria parasite ER.

Acknowledgements

The research described in this article was carried out at the University of Notre Dame and Indiana University School of Medicine-South Bend and was supported by the National Institute of Health grants HL069630, AI039071, HL078826 (K.H) and AI081077 (R.V.S).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Price RN, Douglas NM. Artemisinin combination therapy for malaria: beyond good efficacy. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1638–1640. doi: 10.1086/647947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins WE. Plasmodium knowlesi: a malaria parasite of monkeys and humans. Annual review of entomology. 2012;57:107–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-121510-133540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller LH, et al. The pathogenic basis of malaria. Nature. 2002;415:673–679. doi: 10.1038/415673a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharjee S, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum PI(3)P lipid binding targets malaria proteins to the host cell. Cell. 2012;148:201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haldar K, Mohandas N. Erythrocyte remodeling by malaria parasites. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:203–209. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3280f31b2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon MW, et al. Genetic ablation of a Maurer's cleft protein prevents assembly of the Plasmodium falciparum virulence complex. Mol Microbiol. 2011;81:982–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lauer SA, et al. A membrane network for nutrient import in red cells infected with the malaria parasite. Science. 1997;276:1122–1125. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sargeant TJ, et al. Lineage-specific expansion of proteins exported to erythrocytes in malaria parasites. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Ooij C, et al. The malaria secretome: from algorithms to essential function in blood stage infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000084. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiller NL, et al. A host-targeting signal in virulence proteins reveals a secretome in malarial infection. Science. 2004;306:1934–1937. doi: 10.1126/science.1102737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marti M, et al. Targeting malaria virulence and remodeling proteins to the host erythrocyte. Science. 2004;306:1930–1933. doi: 10.1126/science.1102452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamez PA, et al. An erythrocyte vesicle protein exported by the malaria parasite promotes tubovesicular lipid import from the host cell surface. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000118. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Przyborski JM, Lanzer M. Protein transport and trafficking in Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Parasitology. 2005;130:373–388. doi: 10.1017/s0031182004006729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooke BM, et al. A Maurer's cleft-associated protein is essential for expression of the major malaria virulence antigen on the surface of infected red blood cells. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:899–908. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spielmann T, Gilberger TW. Protein export in malaria parasites: do multiple export motifs add up to multiple export pathways? Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gehde N, et al. Protein unfolding is an essential requirement for transport across the parasitophorous vacuolar membrane of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:613–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang HH, et al. N-terminal processing of proteins exported by malaria parasites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;160:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boddey JA, et al. Role of the Plasmodium export element in trafficking parasite proteins to the infected erythrocyte. Traffic. 2009;10:285–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osborne AR, et al. The host targeting motif in exported Plasmodium proteins is cleaved in the parasite endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2010;171:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boddey JA, et al. An aspartyl protease directs malaria effector proteins to the host cell. Nature. 2010;463:627–631. doi: 10.1038/nature08728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russo I, et al. Plasmepsin V licenses Plasmodium proteins for export into the host erythrocyte. Nature. 2010;463:632–636. doi: 10.1038/nature08726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SA, et al. Targeting of the FYVE domain to endosomal membranes is regulated by a histidine switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13052–13057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503900102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayinger P. Phosphoinositides and vesicular membrane traffic. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821:1104–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishra A, et al. Structural basis for Rab GTPase recognition and endosome tethering by the C2H2 zinc finger of Early Endosomal Autoantigen 1 (EEA1) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10866–10871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000843107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tawk L, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate, an essential lipid in Plasmodium, localizes to the food vacuole membrane and the apicoplast. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9:1519–1530. doi: 10.1128/EC.00124-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waller RF, McFadden GI. The apicoplast: a review of the derived plastid of apicomplexan parasites. Current issues in molecular biology. 2005;7:57–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tawk L, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-monophosphate is involved in toxoplasma apicoplast biogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2010;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001286. e1001286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaid A, et al. PfPI3K, a phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase from Plasmodium falciparum, is exported to the host erythrocyte and is involved in hemoglobin trafficking. Blood. 2010;115:2500–2507. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-238972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kale SD, et al. External lipid PI3P mediates entry of eukaryotic pathogen effectors into plant and animal host cells. Cell. 2010;142:284–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhattacharjee S, et al. The malarial host-targeting signal is conserved in the Irish potato famine pathogen. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez-Estrano C, et al. Cooperative domains define a unique host cell-targeting signal in Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12402–12407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133080100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Koning-Ward TF, et al. A newly discovered protein export machine in malaria parasites. Nature. 2009;459:945–949. doi: 10.1038/nature08104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bullen HE, et al. Biosynthesis, localization, and macromolecular arrangement of the Plasmodium falciparum translocon of exported proteins (PTEX) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:7871–7884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.328591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]