Abstract

Objective

To identify risk factors associated with the highest and lowest prevalence of bullying perpetration among US children.

Methods

Using the 2001–2002 Health Behavior in School-Aged Children, a nationally-representative survey of US children in 6th–10th grades, bivariate analyses were conducted to identify factors associated with any (≥ once or twice), moderate (≥ two-three times/month), and frequent (≥ weekly) bullying. Stepwise multivariable analyses identified risk factors associated with bullying. Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) identified risk factors which, in combination, identify students with the highest and lowest bullying prevalence.

Results

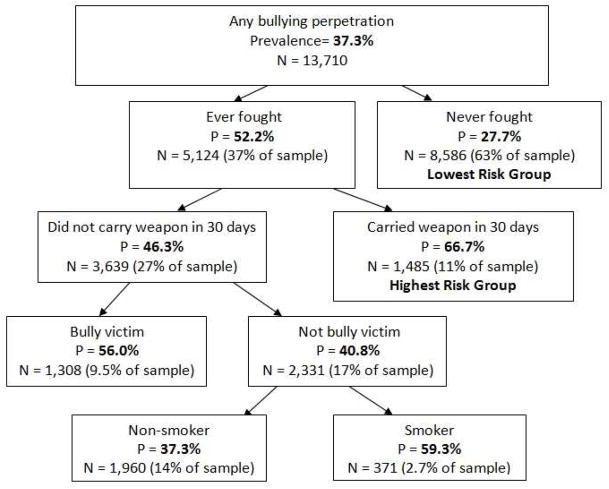

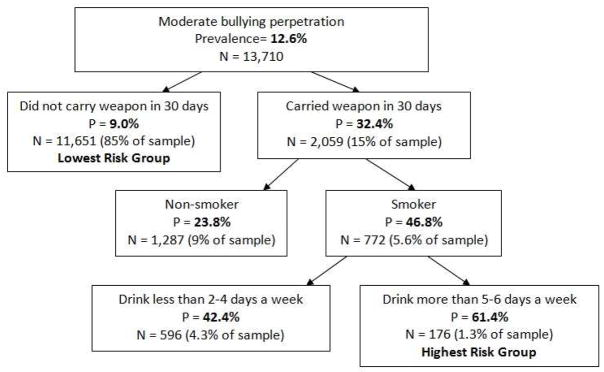

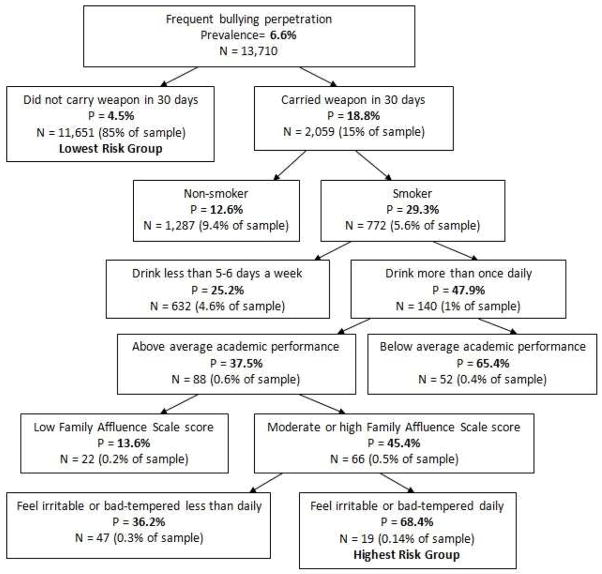

The prevalence of any bullying in the 13,710 students was 37.3%, moderate bullying was 12.6%, and frequent bullying was 6.6%. Characteristics associated with bullying were similar in the multivariable analyses and RPA clusters. In RPA, the highest prevalence of any bullying (67%) accrued in children with a combination of fighting and weapon-carrying. Students who carry weapons, smoke, and drink alcohol more than 5–6 days weekly were at highest risk for moderate bullying (61%). Those who carry weapons, smoke, drink > once daily, have above-average academic performance, moderate/high family affluence, and feel irritable or bad-tempered daily were at highest risk for frequent bullying (68%).

Conclusions

Risk clusters for any, moderate, and frequent bullying differ. Children who fight and carry weapons are at highest risk of any bullying. Weapon-carrying, smoking, and alcohol use are included in the highest risk clusters for moderate and frequent bullying. Risk-group categories may be useful to providers in identifying children at highest risks for bullying and in targeting interventions.

Keywords: bullying, aggression, risk factors, cross-sectional studies

Bullying is an important public health problem in the US, affecting almost one out of three children.1 Perpetrators of bullying have poor school adjustment and academic achievement, increased alcohol use and smoking, and high rates of mental illness.1–4 Long-term outcomes of bullying perpetration include delinquency, criminality, intimate partner violence perpetration, and unemployment.5,6 Bullying often occurs in areas with less adult supervision, such as hallways, playgrounds, and the Internet.7 It is, therefore, difficult to observe directly, and other methods of identification are necessary.8

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that pediatricians address bullying through clinical practice and advocacy.9 Almost 80% of providers believe pediatricians should screen for interpersonal violence-related risk, however,10 only 41% feel confident in their ability to identify at-risk children.10 It may, therefore, be beneficial to identify risk profiles for children at highest risk for being bullies. Studies have examined selected factors that increase the bullying-perpetration risk among children.7–16 Bullies are more likely to be male, 16, depressed,11,12 exposed to child abuse13,14 and domestic violence,13 use alcohol and drugs,15,17 carry weapons,17 fight,1 have poor relationships with classmates,18 and poor parent-child communication.18 These studies examined selected factors associated with bullying at the child, family, and peer level, rather than the concurrent influence of multiple factors. The aim of this study was to identify US children at-risk for bullying perpetration using both multivariable analysis and a targeted-cluster risk factor approach. Multivariable analysis was used to identify the multiple risk and protective factors for being a bully and the targeted-cluster approach to identify children at highest and lowest risk for being bullies.

METHODS

The Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) is a school-based, cross-sectional survey conducted through a World Health Organization (WHO) collaboration in over 30 countries19 to monitor youth health-risk behaviors and attitudes. The 2001–2002 HBSC in the US was a classroom-administered, anonymous survey of children in grades 6–10. A three-stage clustered sampling design was used to provide a nationally-representative sample, with the school district as the first stage, the school as the second stage, and the classroom as the third stage; African-Americans and Latinos were over-sampled. The survey response rate was 81.9%. HBSC survey weights and cluster and strata variables account for the clustered sampling design and provide national estimates. The public-use sample of the 2001–2002 HBSC was used for this study.19

Outcome Variable

Bullying was defined for students as “when another student, or a group of students, say or do nasty or unpleasant things to [the victim]. It is also bullying when a student is teased repeatedly in a way he or she does not like or when they are deliberately left out of things. But it is not bullying when two students of about the same strength or power argue or fight. It is also not bullying when the teasing is done in a friendly and playful way.” The survey item asked: “How often have you bullied another student (s) at school in the past couple of months?” Response options were “none,” “once or twice,” “two or three times a month,” “weekly,” or “several times a week.” This item is based on the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire, and was used to measure bullying in prior studies.1,16–18 Any, moderate, and frequent levels of bullying were examined. A cutoff point of “only once or twice” was used for any bullying, “two or three times a month” for moderate bullying, and “weekly” was used for frequent bullying. Collapsing the two highest response categories for frequent bullying is consistent with prior research using the Olweus Bully/Victim questionnaire.20

Independent Variables

To identify potential risk factors associated with bullying, child, family, peer, and school variables were examined as independent variables, based on previous bullying studies; 1,12,15,16,18 categorization was based on prior HBSC analyses.18,21 The student’s race/ethnicity and gender were categorized based on self-report and included as independent variables in the analyses. The Family Affluence Scale (FAS), has been shown to be a valid, reliable socioeconomic status measure.18,22 It is a four-item index categorized as low, moderate, or high affluence (range 0–7, mean 5.2, SD 1.5).18 Bully victimization was assessed by how often the student reports being bullied in the past couple of months. The five response categories ranged from “never” to “several times a week.” Depression and emotional dysregulation11,12,15 were assessed by how often in the past six months the student felt “low” or “irritable or bad tempered.” The five response categories ranged from “rarely or never” to “about every day.” Frequency of alcohol use was measured as a categorical variable with seven categories, ranging from “never” to “every day, more than once per day.” Current smoking included four categories and lifetime use of marijuana, inhalants, or other drugs was dichotomized (yes/no). Fighting in the past 12 months and weapon-carrying in the past 30 days were dichotomized as never vs. ≥ one time.

Parent school involvement was assessed using two items regarding whether parents were willing to help with homework and to come to school to talk with teachers. Responses were categorized as high, moderate, or low, consistent with prior HBSC analyses.18 Parent communication ease was assessed using two items about how easy it is to talk with the mother and to talk with the father about things that bother the student.18

The social isolation variable consisted of eight items about the number of friends, time spent with friends, and ease of communication with friends.18 Items were re-coded so the highest value reflected the most isolation, standardized to a 0–1 scale, and means of constituent items were calculated (range 0–0.88, mean 0.3, SD 0.1). The bottom tertile (0–0.209) was categorized as low isolation, the middle (0.21–0.669) as moderate, and the top (0.67–0.88) as high. Classmate relationships were measured with four items about classmates’ concern when someone feels down, kindness and helpfulness, acceptance of the respondent, and enjoyment of classmate togetherness.18 Means and tertiles were calculated and categories assigned based on tertiles (range 1–5, mean 2.4, SD 0.9). The highest tertile (2.75–5) was categorized as “good,” the middle (2–2.5) as “average,” and the bottom (1–1.75) as “poor.”

To assess whether academic performance and school maladjustment contributed to bullying behaviors, as found in other research,16 perceived academic achievement was measured by asking students what their teachers think about their school performance. Responses were categorized as very good, good/average, or below average. School satisfaction was assessed by asking students how they feel about school and responses were categorized as high, moderate, or low school satisfaction. School safety is associated with decreased bullying18 and was measured using a five-point Likert scale regarding whether respondents “felt safe at school.” “Strongly agree/agree” responses were categorized as safe, “neither agree nor disagree” as neutral, and “disagree/strongly disagree” as unsafe.

Statistical Methods

Univariate analyses were performed to calculate means or proportions for potential risk factors associated with any, moderate, and frequent bullying, and bivariate analyses evaluated associations between independent variables and bullying, using the Pearson Chi-square test, t-test, or nonparametric Wilcoxon test. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CI) and two-tailed p-values are reported, with p < .05 considered statistically significant.

Multivariable logistic regression, using a two-phase procedure, was used to produce a final parsimonious model of variables associated with bullying, without over-fitting the data.23,24 The first step consisted of a stepwise multivariable analysis. All independent variables were included as initial candidate variables in the procedure. The initial alpha-to-enter was set at 0.15 to capture all potentially important candidate variables, two-tailed p-values were reported, and a p < .05 was considered to be statistically significant for variable inclusion or withdrawal from the model. The second phase consisted of a forced, open multivariable logistic regression, in which statistically significant (p < .05) variables from the first phase were forced into the model and survey weights were used to obtain adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for factors associated with bullying perpetration. Analyses used SAS 9.223 to account for the complex sample design. Separate analyses were conducted for any, moderate, and frequent bullying.

Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) was used to construct a decision tree of risk factors most significantly associated with being a bully. Separate analyses were conducted for any, moderate, and frequent bullying. RPA is a multivariable, targeted-clustering procedure that systematically evaluates all independent variables and identifies variables producing the best binary split, dividing the data into higher risk and lower risk groups with respect to the outcome.24 RPA is nonparametric in nature and does not utilize p values in determining branch-points.24 The best binary split is based on reduction of variance. After each split, the remaining independent variables are examined to find the next split that best separates higher and lower risk groups. This process continues until there are no variables that significantly change the risk in a subpopulation, or the subpopulation is too small to divide. Individuals with missing data for the chosen variable are removed from analysis at that branch point. RPA produces multi-categorical stratification by forming a tree-like pattern of stepwise branching partitions.24 Cross-validation using the 10-fold method and the 1-standard error rule is then conducted, resulting in a tree with the optimal number of branch-points to create the smallest error and prevent over-fitting.25 The hierarchical structure of RPA allows complex nonlinear and higher order interactions to be handled more thoroughly than by interaction terms in linear regression.26 Parametric techniques used with binary variables, such as logistic regression, assume that predictors relate additively and linearly to the logit of the outcome variable.26,27 RPA makes no such assumptions about the distribution of the outcome variable.26,27 RPA does not allow for calculation of the estimated probability of the outcome for each individual,27 but determines the effects of multivariable categories on the dependent variable.24 R 2.9.1 was used to perform the RPA. For each level of bullying (any, moderate, frequent), the bullying odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals between the highest and lowest risk cluster identified from each tree were calculated.28 This study was approved by the UT Southwestern IRB.

RESULTS

The total sample size was 13,710, which represents 15,957,141 children nationwide. About 37% of this sample engaged in any bullying (Table 1), representing 5,958,814 children nationwide; 12.6% engaged in moderate bullying, representing 2,017,558 children nationwide; and 6.6% engaged in frequent bullying, representing 1,055,013 children nationwide. Almost one-third of students in the sample have been bullied by another student in the past couple of months, one in three have been in a fight in the past 12 months, and one in six has carried a weapon in the past 30 days.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of US Children in 6th–10th grades, 2001–2002.

| Characteristic | Weighted Mean (S.E.) or Proportion (95% CI) N=13,710 |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Bullied another student (past couple of months) | |

| Never | 62.7 (61.4, 64.0) |

| Once or twice | 24.7 (23.7, 25.7) |

| Two or three times per month | 6.0 (5.4, 6.6) |

| About once a week | 3.1 (2.7, 3.5) |

| Several times per week | 3.5 (3.1, 3.9) |

|

| |

| Male gender | 47.7 (46.5, 48.8) |

|

| |

| Age, mean | 13.4 (0.1) |

|

| |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 61.2 (57.0, 65.2) |

| Black | 14.2 (11.3, 17.6) |

| Latino | 15.0 (12.8, 17.6) |

| Asian | 3.7 (2.9, 4.8) |

| American Indian | 2.2 (1.6, 3.1) |

| Multiracial | 3.7 (3.2, 4.2) |

|

| |

| Family Affluence Scale | |

| Low | 28.0 (26.1, 30.0) |

| Moderate | 52.1 (50.8, 53.5) |

| High | 19.9 (18.3, 21.5) |

|

| |

| Bullied by another student (past couple of months) | |

| Never | 68.8 (67.5, 70.1) |

| Once or twice | 19.4 (18.4, 20.4) |

| Two or three times per month | 4.3 (3.9, 4.8) |

| About once a week | 2.9 (2.6, 3.3) |

| Several times per week | 4.5 (4.1, 4.9) |

|

| |

| Felt “low” in past six months | |

| About every day | 9.0 (8.4, 9.7) |

| More than once a week | 9.6 (8.9, 10.3) |

| About every week | 10.5 (9.9, 11.2) |

| About every month | 20.4 (19.4, 21.5) |

| Rarely or never | 50.5 (49.1, 51.8) |

|

| |

| Felt irritable or bad tempered in past six months | |

| About every day | 12.6 (11.7, 13.5) |

| More than once a week | 12.7 (12.0, 13.5) |

| About every week | 16.7 (15.8, 17.5) |

| About every month | 25.1 (24.0, 26.2) |

| Rarely or never | 33.0 (31.8, 34.2) |

|

| |

| Times in a fight in past 12 months | |

| None | 62.8 (61.2, 64.4) |

| One or more times | 37.2 (35.7, 38.8) |

|

| |

| Times carried a weapon in last 30 days | |

| None | 84.3 (83.0, 85.5) |

| One or more times | 15.7 (14.5, 17.0) |

|

| |

| Current smoking | |

| None | 84.7 (83.1, 86.2) |

| Less than once a week | 6.7 (5.9, 7.7) |

| At least once a week, but not every day | 3.3 (2.9, 3.8) |

| Every day | 5.3 (4.6, 6.1) |

|

| |

| Other drug use (marijuana/glue/inhalant/other) | 49.1 (46.4, 51.7) |

|

| |

| Number of times per week drank alcohol | |

| Never | 78.3 (76.5, 79.9) |

| Less than once a week | 11.5 (10.5, 12.6) |

| Once a week | 4.1 (3.6, 4.6) |

| 2–4 days a week | 2.6 (2.2, 3.0) |

| 5–6 days a week | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) |

| Daily, once a day | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) |

| Daily, more than once a day | 2.1 (1.7, 2.5) |

|

| |

| Parental school involvement | |

| High | 89.6 (88.8, 90.3) |

| Moderate | 6.5 (5.9, 7.1) |

| Low | 4.0 (3.6, 4.4) |

|

| |

| Parent communication ease | |

| Easy | 85.2 (84.3, 86.0) |

| Difficult | 14.8 (14.0, 15.7) |

|

| |

| Social isolation | |

| Low | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) |

| Moderate | 65.0 (63.5, 66.4) |

| High | 34.0 (32.6, 35.5) |

|

| |

| Classmate relationships | |

| Good | 33.8 (32.2, 35.4) |

| Average | 39.3 (38.1, 40.5) |

| Poor | 26.9 (25.5, 28.4) |

|

| |

| Academic performance | |

| Very good | 25.7 (24.4, 27.0) |

| Good/average | 68.2 (66.9, 69.5) |

| Below average | 6.1 (5.6, 6.8) |

|

| |

| School satisfaction | |

| High | 22.2 (21.0, 23.5) |

| Moderate | 46.3 (45.3, 47.3) |

| Low | 31.5 (30.2, 32.8) |

|

| |

| School safety | |

| Safe | 64.1 (62.1, 66.1) |

| Neutral | 20.7 (19.6, 22.0) |

| Unsafe | 15.2 (14.0, 16.4) |

Bivariate Analyses

Compared with non-bullies, a significantly higher proportion of students engaged in any bullying were male and had been victims of bullying (Table 2a). Bullies were twice as likely to fight, almost three times as likely to carry weapons, and significantly more likely to drink alcohol, smoke, and use other drugs, compared with non-bullies (Table 2a). A significantly higher proportion of students engaged in moderate bullying (Table 2b) were bullied by another student, carried a weapon, smoked, and drank alcohol. A significantly higher proportion of students engaged in frequent bullying (Table 2c) carried a weapon, smoked, drank alcohol, and had below average academic performance. There were slight, but statistically significant, differences in variables such as age.

Table 2a.

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with any (once or twice, two or three times a month, once a week, or several times a week) bullying perpetration in US children in 6th–10th grades.

| Characteristic | Weighted Mean (S.E.) or Proportion (95% CI)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bully (n=5052) | Not Bully (n=8658) | P | |

|

| |||

| Male gender | 53.6 (51.8, 55.4) | 44.1 (42.8, 45.4) | <.01 |

|

| |||

| Age | 13.5 (0.1) | 13.4 (0.1) | <.01 |

|

| |||

| Race/ethnicity | <.01 | ||

| White | 61.3 (57.3, 65.3) | 61.2 (56.8, 65.6) | |

| Black | 12.8 (10.0, 15.7) | 14.9 (11.4, 18.4) | |

| Latino | 16.3 (13.7, 19.0) | 14.3 (11.9, 16.7) | |

| Asian | 3.2 (2.3, 4.1) | 4.1 (3.0, 5.1) | |

| American Indian | 2.3 (1.3, 3.2) | 2.2 (1.4, 2.9) | |

| Multiracial | 4.1 (3.4, 4.9) | 3.4 (2.9, 4.0) | |

|

| |||

| Family Affluence Scale | .06 | ||

| Low | 28.8 (26.7, 30.9) | 26.7 (24.5, 28.9) | |

| Moderate | 51.9 (50.3, 53.5) | 52.6 (50.7, 54.5) | |

| High | 19.3 (17.6, 21.0) | 20.7 (18.8, 22.6) | |

|

| |||

| Bullied by another student (past couple of months) | <.01 | ||

| Never | 57.0 (55.2, 58.7) | 75.8 (74.5, 77.2) | |

| Once or twice | 26.2 (24.5, 27.8) | 15.4 (14.4, 16.4) | |

| Two or three times per month | 6.6 (5.7, 7.5) | 2.9 (2.5, 3.3) | |

| About once a week | 4.1 (3.4, 4.9) | 2.2 (1.9, 2.6) | |

| Several times per week | 6.1 (5.3, 6.9) | 3.6 (3.1, 4.0) | |

|

| |||

| Felt “low” in past six months | <.01 | ||

| About every day | 11.5 (10.5, 12.5) | 7.6 (6.8, 8.3) | |

| More than once a week | 11.3 (10.1, 12.5) | 8.6 (7.7, 9.4) | |

| About every week | 12.3 (11.2, 13.4) | 9.5 (8.7, 10.2) | |

| About every month | 22.1 (20.5, 23.7) | 19.4 (18.2, 20.5) | |

| Rarely or never | 42.8 (41.0, 44.5) | 55.0 (53.3, 56.6) | |

|

| |||

| Felt irritable or bad tempered in past six months | <.01 | ||

| About every day | 17.0 (15.5, 18.5) | 10.0 (9.1, 10.9) | |

| More than once a week | 16.2 (15.0, 17.4) | 10.7 (9.7, 11.6) | |

| About every week | 19.4 (17.9, 20.8) | 15.1 (14.0, 16.1) | |

| About every month | 24.1 (22.4, 25.9) | 25.6 (24.4, 26.8) | |

| Rarely or never | 23.3 (21.6, 25.1) | 38.7 (37.1, 40.3) | |

|

| |||

| Times in a fight in past 12 months | <.01 | ||

| None | 47.1 (45.1, 49.2) | 72.1 (70.6, 73.7) | |

| One or more times | 52.9 (50.8, 54.9) | 27.9 (26.3, 29.4) | |

|

| |||

| Times carried a weapon in last 30 days | <.01 | ||

| None | 74.3 (72.3, 76.3) | 90.2 (89.1, 91.3) | |

| One or more times | 25.7 (23.7, 27.7) | 9.8 (8.7, 10.9) | |

|

| |||

| Current smoking | <.01 | ||

| None | 75.9 (73.6, 78.3) | 90.0 (88.7, 91.2) | |

| Less than once a week | 10.6 (9.0, 12.2) | 4.4 (3.7, 5.2) | |

| At least once a week, but not every day | 4.9 (4.1, 5.7) | 2.3 (1.9, 2.8) | |

| Every day | 8.6 (7.3, 9.9) | 3.3 (2.8, 3.8) | |

|

| |||

| Other drug use (marijuana/glue/inhalant/other) | 64.4 (61.1, 67.6) | 38.6 (35.8, 41.3) | <.01 |

|

| |||

| Number times a week drank alcohol | <.01 | ||

| Never | 68.5 (66.3, 70.7) | 84.0 (82.4, 85.6) | |

| Less than once a week | 16.2 (14.7, 17.7) | 8.7 (7.5, 9.9) | |

| Once a week | 5.6 (4.7, 6.4) | 3.2 (2.6, 3.7) | |

| 2–4 days a week | 3.8 (3.0, 4.5) | 1.8 (1.4, 2.2) | |

| 5–6 days a week | 1.5 (1.0, 1.9) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7) | |

| Once a day, every day | 1.1 (0.7, 1.4) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | |

| Every day, more than once | 3.4 (2.7, 4.2) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.5) | |

|

| |||

| Parental school involvement | <.01 | ||

| High | 87.8 (86.6, 88.9) | 90.7 (89.9, 91.4) | |

| Moderate | 7.7 (6.7, 8.6) | 5.7 (5.0, 6.4) | |

| Low | 4.6 (3.9, 5.3) | 3.6 (3.2, 4.1) | |

|

| |||

| Parent communication ease | <.01 | ||

| Easy | 83.5 (82.3, 84.7) | 86.2 (85.1, 87.2) | |

| Difficult | 16.5 (15.3, 17.7) | 13.8 (12.8, 14.9) | |

|

| |||

| Social isolation | <.01 | ||

| Low | 0.8 (0.5, 1.1) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) | |

| Moderate | 61.6 (59.5, 63.7) | 67.0 (65.5, 68.6) | |

| High | 37.6 (35.5, 39.7) | 31.9 (30.3, 33.5) | |

|

| |||

| Classmate relationships | <.01 | ||

| Good | 22.5 (20.7, 24.4) | 29.5 (27.8, 31.2) | |

| Average | 37.5 (35.8, 39.2) | 40.4 (39.0, 41.7) | |

| Poor | 40.0 (37.8, 42.1) | 30.1 (37.8, 42.1) | |

|

| |||

| Academic performance | <.01 | ||

| Very good | 20.8 (19.3, 22.3) | 28.6 (27.0, 30.2) | |

| Good/average | 70.7 (69.0, 72.4) | 66.7 (65.1, 68.2) | |

| Below average | 8.5 (7.4, 9.6) | 4.7 (4.2, 5.3) | |

|

| |||

| School satisfaction | <.01 | ||

| High | 17.1 (15.6, 18.5) | 25.3 (23.8, 26.8) | |

| Moderate | 45.6 (43.9, 47.4) | 46.7 (45.5, 47.8) | |

| Low | 37.3 (35.3, 39.3) | 28.0 (26.5, 29.4) | |

|

| |||

| Feel safe at school | <.01 | ||

| Safe | 57.6 (55.3, 60.0) | 68.0 (65.9, 70.1) | |

| Neutral | 24.0 (22.3, 25.6) | 18.8 (17.4, 20.2) | |

| Unsafe | 18.4 (16.7, 20.1) | 13.2 (11.9, 14.5) | |

Table 2b.

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with moderate (two or three times a month, once a week, or several times a week) bullying perpetration in US children in 6th–10th grades.

| Characteristic | Weighted Mean (S.E.) or Proportion (95% CI)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bully (n=1714) | Not Bully (n=11996) | P | |

|

| |||

| Male gender | 64.7 (61.8, 67.6) | 45.2 (44.0, 46.4) | <.01 |

|

| |||

| Age | 13.4 (0.1) | 13.6 (0.1) | <.01 |

|

| |||

| Race/ethnicity | <.01 | ||

| White | 56.5 (51.5, 61.6) | 61.9 (57.7, 66.0) | |

| Black | 15.6 (12.0, 19.3) | 13.9 (10.7, 17.1) | |

| Latino | 17.3 (14.2, 20.3) | 14.7 (12.3, 17.1) | |

| Asian | 3.1 (2.0, 4.2) | 3.8 (2.9, 4.8) | |

| American Indian | 3.2 (1.8, 4.6) | 2.0 (1.3, 2.7) | |

| Multiracial | 4.2 (3.0, 5.5) | 3.6 (3.1, 4.1) | |

|

| |||

| Family Affluence Scale | .13 | ||

| Low | 29.6 (26.3, 33.0) | 27.8 (25.8, 29.7) | |

| Moderate | 49.3 (46.0, 52.6) | 52.5 (51.1, 54.0) | |

| High | 21.1 (18.5, 23.7) | 19.7 (18.0, 21.3) | |

|

| |||

| Bullied by another student (past couple of months) | <.01 | ||

| Never | 55.1 (52.0, 58.2) | 70.8 (69.5, 72.1) | |

| Once or twice | 20.7 (18.1, 23.4) | 19.3 (18.2, 20.3) | |

| Two or three times per month | 8.5 (6.9, 10.2) | 3.7 (3.3, 4.1) | |

| About once a week | 6.1 (4.4, 7.8) | 2.4 (2.1, 2.9) | |

| Several times per week | 9.6 (7.9, 11.3) | 3.8 (3.4, 4.2) | |

|

| |||

| Felt “low” in past six months | <.01 | ||

| About every day | 15.4 (13.4, 17.4) | 8.1 (7.5, 8.8) | |

| More than once a week | 12.3 (10.3, 14.4) | 9.2 (8.5, 9.9) | |

| About every week | 13.0 (11.1, 14.8) | 10.2 (9.5, 10.9) | |

| About every month | 17.3 (14.9, 19.7) | 20.8 (19.7, 21.9) | |

| Rarely or never | 42.0 (39.3, 44.8) | 51.7 (50.2, 53.1) | |

|

| |||

| Felt irritable or bad tempered in past six months | <.01 | ||

| About every day | 24.6 (22.0, 27.1) | 10.9 (10.0, 11.7) | |

| More than once a week | 16.4 (14.3, 18.5) | 12.2 (11.4, 13.0) | |

| About every week | 18.3 (16.3, 20.4) | 16.4 (15.5, 17.3) | |

| About every month | 18.6 (16.2, 20.9) | 26.0 (24.9, 27.1) | |

| Rarely or never | 22.1 (19.6, 24.6) | 34.5 (33.2, 35.8) | |

|

| |||

| Times in a fight in past 12 months | <.01 | ||

| None | 33.2 (30.6, 35.7) | 67.1 (65.5, 68.6) | |

| One or more times | 66.8 (64.3, 69.4) | 32.9 (31.4, 34.5) | |

|

| |||

| Times carried a weapon in last 30 days | <.01 | ||

| None | 59.1 (55.9, 62.3) | 87.9 (86.8, 89.0) | |

| One or more times | 40.9 (37.7, 44.1) | 12.1 (11.0, 13.2) | |

|

| |||

| Current smoking | <.01 | ||

| None | 62.1 (58.5, 65.7) | 88.0 (86.6, 89.3) | |

| Less than once a week | 14.2 (11.7, 16.8) | 5.7 (4.8, 6.5) | |

| At least once a week, but not every day | 8.0 (6.3, 9.6) | 2.6 (2.2, 3.0) | |

| Every day | 15.7 (13.3, 18.1) | 3.8 (3.1, 4.4) | |

|

| |||

| Other drug use (marijuana/glue/inhalant/other) | 78.2 (74.6, 81.7) | 43.9 (41.1, 46.6) | <.01 |

|

| |||

| Number times a week drank alcohol | <.01 | ||

| Never | 56.8 (53.2, 60.5) | 81.3 (79.7, 82.8) | |

| Less than once a week | 18.9 (16.3, 21.4) | 10.4 (9.4, 11.5) | |

| Once a week | 6.7 (4.9, 8.4) | 3.7 (3.2, 4.2) | |

| 2–4 days a week | 5.3 (3.9, 6.6) | 2.2 (1.8, 2.6) | |

| 5–6 days a week | 2.8 (1.8, 3.7) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8) | |

| Once a day, every day | 1.9 (1.0, 2.7) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7) | |

| Every day, more than once | 7.7 (6.1, 9.4) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.6) | |

|

| |||

| Parental school involvement | <.01 | ||

| High | 81.3 (79.0, 83.5) | 90.8 (90.1, 91.5) | |

| Moderate | 10.5 (8.7, 12.4) | 5.9 (5.3, 6.5) | |

| Low | 8.2 (6.5, 9.9) | 3.4 (3.0, 3.8) | |

|

| |||

| Parent communication ease | <.01 | ||

| Easy | 80.7 (78.3, 83.1) | 85.8 (84.9, 86.7) | |

| Difficult | 19.3 (16.9, 21.7) | 14.2 (13.3, 15.1) | |

|

| |||

| Social isolation | <.01 | ||

| Low | 0.7 (0.2, 1.2) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | |

| Moderate | 56.3 (52.7, 59.9) | 66.2 (64.7, 67.6) | |

| High | 43.0 (39.4, 46.6) | 32.8 (31.3, 34.3) | |

|

| |||

| Classmate relationships | <.01 | ||

| Good | 20.4 (18.0, 22.7) | 27.9 (26.3, 29.4) | |

| Average | 30.3 (27.6, 32.9) | 40.6 (39.3, 41.8) | |

| Poor | 49.4 (46.2, 52.5) | 31.6 (30.0, 33.1) | |

|

| |||

| Academic performance | <.01 | ||

| Very good | 19.1 (16.8, 21.5) | 26.6 (25.3, 28.0) | |

| Good/average | 65.7 (62.9, 68.5) | 68.5 (67.2, 69.9) | |

| Below average | 15.2 (12.9, 17.5) | 4.8 (4.3, 5.4) | |

|

| |||

| School satisfaction | <.01 | ||

| High | 14.1 (12.0, 16.1) | 23.4 (22.1, 24.8) | |

| Moderate | 37.3 (34.8, 39.8) | 47.6 (46.6, 48.6) | |

| Low | 48.6 (45.7, 51.6) | 29.0 (27.7, 30.3) | |

|

| |||

| Feel safe at school | <.01 | ||

| Safe | 49.6 (46.0, 53.2) | 66.2 (64.2, 68.1) | |

| Neutral | 23.1 (20.8, 25.4) | 20.4 (19.1, 21.7) | |

| Unsafe | 27.3 (24.0, 30.6) | 13.4 (12.3, 14.6) | |

Table 2c.

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with frequent (once a week or several times a week) bullying perpetration in US children in 6th–10th grades.

| Characteristic | Weighted Mean (S.E.) or Proportion (95% CI)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bully (n=914) | Not Bully (n=12796) | P | |

|

| |||

| Male gender | 66.6 (62.9, 70.5) | 46.3 (45.1, 47.5) | <.01 |

|

| |||

| Age | 13.6 (0.1) | 13.4 (0.1) | <.01 |

|

| |||

| Race/ethnicity | <.01 | ||

| White | 53.6 (47.6, 59.7) | 61.7 (57.6, 65.8) | |

| Black | 17.2 (13.0, 21.4) | 13.9 (10.8, 17.1) | |

| Latino | 18.8 (14.9, 22.7) | 14.8 (12.3, 17.2) | |

| Asian | 3.1 (1.7, 4.5) | 3.8 (2.9, 4.7) | |

| American Indian | 3.3 (1.6, 5.0) | 2.1 (1.4, 2.8) | |

| Multiracial | 4.0 (2.6, 5.4) | 3.7 (3.2, 4.2) | |

|

| |||

| Family Affluence Scale | .05 | ||

| Low | 31.6 (27.6, 35.6) | 27.8 (25.8, 29.7) | |

| Moderate | 47.7 (43.7, 51.7) | 52.4 (51.1, 53.8) | |

| High | 20.7 (17.4, 23.9) | 19.8 (18.1, 21.4) | |

|

| |||

| Bullied by another student (past couple of months) | <.01 | ||

| Never | 58.0 (54.6, 61.3) | 69.6 (68.3, 70.9) | |

| Once or twice | 18.7 (15.9, 21.5) | 19.5 (18.5, 20.5) | |

| Two or three times per month | 5.9 (4.1, 7.8) | 4.2 (3.8, 4.6) | |

| About once a week | 6.2 (4.0, 8.5) | 2.7 (2.3, 3.1) | |

| Several times per week | 11.2 (8.4, 13.9) | 4.0 (3.6, 4.5) | |

|

| |||

| Felt “low” in past six months | <.01 | ||

| About every day | 20.0 (16.9, 23.1) | 8.3 (7.6, 8.9) | |

| More than once a week | 10.9 (8.3, 13.4) | 9.5 (8.8, 10.2) | |

| About every week | 10.5 (8.1, 12.8) | 10.5 (9.9, 11.2) | |

| About every month | 15.0 (11.9, 18.1) | 20.8 (19.7, 21.8) | |

| Rarely or never | 43.7 (39.6, 47.7) | 50.9 (49.6, 52.3) | |

|

| |||

| Felt irritable or bad tempered in past six months | <.01 | ||

| About every day | 29.5 (26.2, 32.8) | 11.4 (10.6, 12.3) | |

| More than once a week | 15.6 (12.4, 18.7) | 12.5 (11.7, 13.3) | |

| About every week | 15.5 (12.6, 18.3) | 16.7 (15.9, 17.6) | |

| About every month | 16.3 (13.4, 19.2) | 25.7 (24.6, 26.8) | |

| Rarely or never | 23.2 (19.8, 26.5) | 33.6 (32.4, 34.9) | |

|

| |||

| Times in a fight in past 12 months | <.01 | ||

| None | 29.9 (26.6, 33.2) | 65.1 (63.6, 66.7) | |

| One or more times | 70.1 (66.8, 73.4) | 34.9 (33.3, 36.4) | |

|

| |||

| Times carried a weapon in last 30 days | <.01 | ||

| None | 53.7 (49.7, 57.8) | 86.4 (85.2, 87.6) | |

| One or more times | 46.3 (42.2, 50.3) | 13.6 (12.4, 14.8) | |

|

| |||

| Current smoking | <.01 | ||

| None | 57.1 (52.6, 61.6) | 86.7 (85.2, 88.1) | |

| Less than once a week | 14.0 (11.1, 16.9) | 6.2 (5.3, 7.1) | |

| At least once a week, but not every day | 7.6 (5.6, 9.6) | 3.0 (2.5, 3.4) | |

| Every day | 21.3 (17.8, 24.9) | 4.1 (3.5, 4.8) | |

|

| |||

| Other drug use (marijuana/glue/inhalant/other) | 82.0 (77.1, 86.9) | 46.2 (43.4, 48.9) | <.01 |

|

| |||

| Number times a week drank alcohol | |||

| Never | 53.6 (48.8, 58.3) | 79.9 (78.3, 81.6) | |

| Less than once a week | 18.5 (15.1, 21.9) | 11.0 (9.9, 12.1) | |

| Once a week | 6.4 (4.2, 8.6) | 3.9 (3.4, 4.4) | <.01 |

| 2–4 days a week | 5.3 (3.6, 7.0) | 2.4 (2.0, 2.8) | |

| 5–6 days a week | 2.4 (1.1, 3.8) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) | |

| Once a day, every day | 2.7 (1.3, 4.1) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.7) | |

| Every day, more than once | 11.1 (8.6, 13.6) | 1.5 (1.1, 1.8) | |

|

| |||

| Parental school involvement | |||

| High | 78.6 (75.1, 82.1) | 90.3 (89.6, 91.0) | <.01 |

| Moderate | 10.2 (7.8, 12.6) | 6.2 (5.6, 6.8) | |

| Low | 11.2 (8.5, 14.0) | 3.5 (3.1, 3.9) | |

|

| |||

| Parent communication ease | |||

| Easy | 79.0 (75.5, 82.5) | 85.6 (84.8, 86.5) | <.01 |

| Difficult | 21.0 (17.5, 24.5) | 14.4 (13.5, 15.2) | |

|

| |||

| Social isolation | |||

| Low | 1.0 (0.1, 2.0) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) | <.01 |

| Moderate | 53.8 (49.0, 58.6) | 65.7 (64.3, 67.2) | |

| High | 45.2 (40.6, 49.8) | 33.3 (31.8, 34.8) | |

|

| |||

| Classmate relationships | |||

| Good | 19.1 (15.7, 22.5) | 27.5 (25.9, 29.0) | <.01 |

| Average | 28.8 (25.0, 32.7) | 40.0 (38.8, 41.2) | |

| Poor | 52.1 (47.8, 56.3) | 32.5 (31.0, 34.1) | |

|

| |||

| Academic performance | |||

| Very good | 20.2 (16.7, 23.8) | 26.1 (24.8, 27.4) | <.01 |

| Good/average | 59.6 (55.7, 63.6) | 68.8 (67.5, 70.1) | |

| Below average | 20.1 (16.9, 23.4) | 5.2 (4.6, 5.7) | |

|

| |||

| School satisfaction | |||

| High | 12.5 (9.9, 15.2) | 22.9 (21.6, 24.2) | <.01 |

| Moderate | 33.6 (29.7, 37.5) | 47.2 (46.2, 48.2) | |

| Low | 53.8 (49.9, 57.8) | 29.9 (28.6, 31.2) | |

|

| |||

| Feel safe at school | |||

| Safe | 44.2 (40.0, 48.4) | 65.5 (63.6, 67.5) | <.01 |

| Neutral | 21.1 (18.4, 23.8) | 20.7 (19.5, 22.0) | |

| Unsafe | 34.7 (30.4, 39.0) | 13.8 (12.6, 14.9) | |

Multivariable Analysis

Children who fought in the past 12 months had almost double the odds of any bullying (Table 3a). Victims of bullying, drug use, carrying a weapon in the past 30 days, males, and children who reported feeling irritable or bad tempered in the past six months also had higher adjusted odds of any bullying. Moderate or low (vs. high) school satisfaction and having good/average (vs. very good) academic performance were associated with increased odds of bullying. Below average (vs. very good) academic performance was not significantly associated with any bullying. African-American, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American-Indian/Alaskan Native children had lower odds of any bullying, compared with whites.

Table 3a.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with any bullying perpetration*

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) of Bullying |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Fought in past 12 months | 1.9 (1.6, 2.2) |

|

| |

| Bullied by another student (past couple of months) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.4) |

|

| |

| Other drug use (marijuana/glue/inhalant/other) | 1.6 (1.3, 1.9) |

|

| |

| Carried a weapon in last 30 days | 1.5 (1.2, 1.8) |

|

| |

| Male gender | 1.3 (1.2, 1.6) |

|

| |

| Felt irritable or bad tempered in past six months | 1.3 (1.2, 1.32) |

|

| |

| School satisfaction | |

| High | Reference |

| Moderate | 1.3 (1.1, 1.7) |

| Low | 1.3 (1.04, 1.6) |

|

| |

| Academic performance | |

| Very good | Reference |

| Good/average | 1.3 (1.03, 1.6) |

| Below average | 1.2 (0.9, 1.8) |

|

| |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | Reference |

| African American | 0.7 (0.6, 0.9) |

| Latino | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) |

| Asian | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) |

| American Indian | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) |

| Multiracial | 1.0 (0.6, 1.5) |

|

| |

| Current weekly alcohol use | 1.1 (1.00, 1.15) |

Significant odds ratios, based on 95% confidence intervals, are highlighted in bold

Children with good/average or below average (vs. very good) academic performance had higher odds of moderate bullying (Table 3b). Fighting, male gender, and drug use also were associated with higher adjusted odds of moderate bullying. High (vs. low) family affluence was associated with increased odds of moderate bullying. Weapon-carrying in the past 30 days, feeling irritable or bad tempered in the past six months, and drinking alcohol also increased the odds of moderate bullying.

Table 3b.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with moderate bullying perpetration*

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) of Bullying |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Academic performance | |

| Very good | Reference |

| Good/average | 1.6 (1.2, 2.1) |

| Below average | 2.4 (1.5, 3.7) |

|

| |

| Fought in past 12 months | 2.2 (1.8, 2.8) |

|

| |

| Male gender | 2.0 (1.6, 2.6) |

|

| |

| Other drug use (marijuana/glue/inhalant/other) | 2.0 (1.6, 2.5) |

|

| |

| Family Affluence Scale | |

| Low | Reference |

| Moderate | 1.3 (0.95, 1.7) |

| High | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) |

|

| |

| Carried a weapon in last 30 days | 1.6 (1.2, 2.1) |

|

| |

| Felt irritable or bad tempered in past six months | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) |

|

| |

| Current weekly alcohol use | 1.2 (1.1, 1.25) |

Significant odds ratios, based on 95% confidence intervals, are highlighted in bold

Among children with frequent bullying perpetration, below average (vs. very good) academic performance was associated with more than double the odds of bullying (Table 3c). Fighting, male gender, and drug use were associated with more than double the odds of frequent bullying. Weapon-carrying in the past 30 days, feeling irritable or bad tempered in the past six months, and alcohol use also were associated with higher odds of frequent bullying, whereas age of the child was associated with lower odds of bullying.

Table 3c.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with frequent bullying perpetration*

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) of Bullying |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Academic performance | |

| Very good | Reference |

| Good/average | 1.4 (0.9, 2.1) |

| Below average | 2.5 (1.5, 4.0) |

|

| |

| Fought in past 12 months | 2.2 (1.5, 3.2) |

|

| |

| Male gender | 2.1 (1.5, 2.9) |

|

| |

| Other drug use (marijuana/glue/inhalant/other) | 2.1 (1.3, 3.1) |

|

| |

| Carried a weapon in last 30 days | 1.8 (1.3, 2.4) |

|

| |

| Felt irritable or bad tempered in past six months | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) |

|

| |

| Current weekly alcohol use | 1.2 (1.15, 1.3) |

|

| |

| Age, mean | 0.8 (0.76, 0.93) |

Significant odds ratios, based on 95% confidence intervals, are highlighted in bold

Recursive Partitioning Analysis

Recursive partitioning analysis for any bullying yielded a tree in which being in a fight in the past 12 months was the initial splitting variable (Fig. 1). Among 5,124 children who fought (37% of the full sample), 52% were bullies; among those who did not fight (63% of the full sample), 28% were bullies. Among fighters, the prevalence of bullying was 67% in children who carried a weapon in the past 30 days, vs. 46% in children who did not carry a weapon. For fighting, non-weapon-carrying children, the bullying perpetration prevalence was 56% for those who were victims of bullying in the past couple of months, vs. 41% in those who were not victims of bullying. The bullying prevalence was 59% among fighting, non-weapon-carrying, non-bullied children who smoked, vs. 37% for non-smokers.

Figure 1.

Recursive partitioning analysis of clusters of factors associated with any bullying perpetration (once or twice, two or three a month, once a week, or several times a week) among US children.

RPA for moderate bullying yielded a tree in which carrying a weapon in the past 30 days was the initial splitting variable (Fig. 2). Among children who carried a weapon (10% of the full sample), 32% were bullies. The second splitting variable was smoking, and the last was alcohol use. The lowest prevalence of bullying (9%) was in those who did not carry a weapon, and the highest (61%) was in those who carried a weapon, smoked, and drank more than 5–6 days per week. In the RPA for frequent bullying (Fig. 3), the first splitting variable was weapon-carrying. The group with the lowest bullying prevalence (4.5%) was those who did not carry a weapon. The subsequent splitting variables were smoking, alcohol use, academic performance, family affluence, and feeling irritable/bad-tempered. The bullying prevalence was highest for the risk cluster of children who carried a weapon, smoked, drank more than once daily, had above average-academic performance, moderate/high family affluence, and felt irritable/bad-tempered daily (68%), followed by children who carried a weapon, smoked, drank more than once daily, and had below-average academic performance (65%). The bullying perpetration odds ratio (OR) between the highest and lowest risk groups among those with any bullying perpetration was 5.3 (95% CI, 4.7–6.0), moderate bullying was 6.4 (95% CI, 4.7–8.7), and frequent bullying was 14.5 (95% CI, 7.1–29.5).

Figure 2.

Recursive partitioning analysis of clusters of factors associated with moderate bullying perpetration (two or three times a month, once a week, or several times a week) among US children.

Figure 3.

Recursive partitioning analysis of clusters of factors associated with frequent bullying perpetration (once a week or several times a week) among US children.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of bullying at least once or twice in this sample was 37%, bullying at least two-three times monthly was 13%, and at least once weekly was 7%. The risk clusters for highest and lowest bullying prevalence were different for any, moderate, and frequent bullying perpetration. Students who both fight and carry weapons are at highest risk for engaging in any bullying. Students who have not fought in the past year are at lowest risk. Students who carry weapons, smoke, and drink alcohol more than 5–6 days weekly are at highest risk for engaging in moderate bullying. Those who carry a weapon, smoke, drink more than once daily, have above average academic performance, moderate/high family affluence, and feel irritable or bad-tempered daily are at highest risk for frequent bullying. Characteristics associated with bullying are similar in the multivariable analyses and RPA clusters.

Multivariable analysis algebraically examines the independent influence of each individual factor on bullying, whereas RPA examines the combined influence of a cluster of factors on bullying, and can help identify risk profiles for bullying.24 Given that targeted clusters contain multiple factors and reveal the prevalence of bullying only among children who have all of these factors, this method does not identify all bullies, but rather focuses on children who are most and least likely to be bullies. The two methods provide different types of information which can be used to identify bullying risk in children. Using both methods with the same dataset provides a more comprehensive representation of risk factors and risk profiles that can be useful in identifying potential bullies. Risk factors which are consistent in both multivariable analysis and RPA may be especially important.

Results of RPA and multivariable analyses of bullying show some consistency, with multivariable analyses identifying a larger number of factors associated with bullying, and RPA identifying clusters of factors associated with the highest and lowest prevalence of bullying. For children with multiple risk factors for bullying, RPA reveals clusters of characteristics identifying the highest-prevalence group. Odds ratios comparing children in the highest-risk group cluster with those who do not have these characteristics, show substantially higher odds of bullying in the highest-risk groups.

Three of the four characteristics in the high-risk RPA cluster for any bullying (fighting, being bullied, and weapon-carrying) also are associated with the highest odds of bullying in multivariable analysis. A child who has been in a fight or been bullied has almost twice the odds of any bullying. Multivariable analysis identifies several additional characteristics associated with bullying. Male gender, feeling irritable/bad-tempered, lower level of school satisfaction, and worse academic performance increase the odds of bullying.

In the multivariable analysis for moderate bullying, weapon-carrying and alcohol use are associated with increased odds of bullying, consistent with the RPA. In addition, worse academic performance, fighting, male gender, feeling irritable/bad-tempered, and high family affluence are associated with increased odds of bullying. Family affluence is not in the RPA cluster for moderate bullying. It is, however, in the RPA for frequent bullying, with higher family affluence associated with increased bullying. Four out of six factors identified in the RPA for frequent bullying also were identified in multivariable analysis. Below average academic performance is associated with two and a half times the odds of bullying. This is consistent with the RPA results, in which, among children who carry a weapon, smoke, and drink, those with below-average academic performance have a frequent bullying prevalence of 65.4%, whereas children with above-average performance have a frequent bullying prevalence of 37.5%. The highest risk group RPA cluster, however, includes above-average academic performance. This suggests that poor academic performance alone may be associated with higher risk of bullying; however, among children with the combined characteristics of weapon-carrying, smoking, drinking, and above-average academic performance, moderate/high family affluence, and feeling irritable/bad-tempered daily yielded the highest bullying prevalence (68.4%).

For all three levels of bullying, smoking is included in the RPA tree, whereas other drug use is significantly associated with bullying in the multivariable analyses. This may be because smoking is not significantly associated with bullying when adjusting for other drug use, but may be important in combination with, rather than adjusting for, other factors, such as fighting, weapon-carrying, and bully victimization, as occurs in the RPA clusters.

It was important to include fighting as an independent variable, as it has been shown to be associated with bullying perpetration in previous studies.29 Fighting is associated with bullying in multivariable analyses for all three levels of bullying, whereas it is in the RPA tree only for any bullying. It is possible that students may report the same incident of aggression as both fighting and bullying, resulting in endogeneity. The definition of bullying given to the students, however, specifically states that it is not bullying when participants in a fight are of the same strength or power, and almost half the students reporting any bullying had not been in a fight. The RPA results may reflect a difference in the type of bullying, with those in the any bullying group engaging in more physical bullying, and moderate and frequent bullies engaging in more verbal or relational bullying. It also may be easier to identify the overtly physical aggressive behavior of fighting than the sometimes less overt bullying behaviors.

Studies show that there is heterogeneity among bullies.30 Some bullies have well-developed social skills and use bullying to maintain their dominant status in a peer group.30 Others are impulsively aggressive, and have psychological problems, poor social skills, and poor peer-relationships.30 These include aggressive or provocative victims, who respond with aggression to being bullied and may be bully-victims,30 who have the broadest range of adjustment problems.3,6 One longitudinal study examining bullying trajectories showed that a small proportion were bully-victims, with 3% showing increasing bullying with concurrently decreasing victimization, suggesting a transition from victimization to bullying.30 In our study, victimization was associated with bullying in multivariable analysis and was part of the risk cluster for any bullying only. This group may include bully-victims or victims who have begun to transition to perpetration.

Bullies may differ based on the frequency and chronicity of bullying. One study6 categorized 10% of students as exhibiting consistently high rates of bullying over time (high-bullying group), 35% in the moderate-bullying group, and 42% in the never-bullying group. Thirteen percent of students were in the “desist” group, exhibiting moderate bullying in early adolescence, but almost none by the end of high school.6 Children in these three groups differ in the quality of their relationships with parents and peers.6 This study emphasizes the examination of bullying frequency and that frequent bullies may have different risk profiles from less frequent bullies.6 Our study indicates that risk factors and risk clusters are different for any, moderate, and frequent bullying, although there is some overlap. Weapon-carrying and smoking are included in the risk clusters for all levels of bullying. The first three splitting variables for both moderate and frequent bullying are weapon-carrying, smoking, and alcohol use. Risk factors associated with bullying in multivariable analyses also are similar for the moderate and frequent bullying groups, suggesting that moderate and frequent bullies may be more similar to each other than to those in the any bullying group.

In 2009, 18% of US students in 9th–12th grades reported weapon-carrying in the past 30 days, 42% drank alcohol, 20% smoked, and 32% reported physical fighting in the past year.31 Bullying is associated with higher rates of smoking, externalizing behavior, and excessive alcohol use.4,12,20 These relationships between bullying and risky behaviors persist into adulthood.32 Our study shows that children who fight and carry weapons have five times the odds of any bullying compared with non-fighters; children who carry weapons, smoke, and drink frequently have six times the odds of moderate bullying compared with non-weapon-carrying children; and children who carry weapons, smoke, drink frequently, have above average academic performance, moderate/high family affluence, and feel irritable/bad-tempered daily have 14.5 times the odds of frequent bullying, compared with non-weapon-carrying children. Fighting, weapon-carrying, and drug and alcohol use also are associated with bullying in multivariable analyses. Findings from this study can be interpreted in the context of Jessor’s Problem Behavior Theory, which proposes a syndrome of problem behavior among adolescents, with the co-occurrence of multiple health-risk behaviors, such as alcohol use, substance use, and violence.33 The inter-relatedness of these behaviors may reflect an underlying proneness to problem behavior which manifests as high-risk health behaviors such as bullying. It is important to address all of these problem behaviors with effective interventions. Relationships between these problem behaviors and bullying are consistent using both types of analyses. Although it is not possible to determine whether the presence of these high-risk behaviors predicts later bullying risk, the cross-sectional data in this study suggest that these high-risk problem behaviors co-occur with bullying. Children identified with these problem behaviors, such as fighting, weapon-carrying, smoking, and drinking, also should be evaluated for bullying, so that interventions can include bullying-prevention components.

Currently, various methods are used to identify bullies, with variable results.8 Child self-report may underestimate bullying, as children may be less likely to identify themselves as bullies.8 Teacher reports may be limited by observation of children in a restricted number of contexts, such as one classroom.8 Direct observations are unbiased, but fail to correlate well over time, and may not be feasible in all settings where bullying occurs, such as locker rooms and bathrooms.8 Student self-reports are most highly correlated with identification as bullies/victims by peers (peer nominations); peer nomination and student self-reports are most likely to identify covert episodes of bullying.8 The clustered risk groups identified in this study may be another option in identifying bullies. Information about fighting, weapon-carrying, drug use, and smoking is assessed by providers through methods such as the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS) questionnaires.34 Physician groups, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Medical Association, have policy statements and educational resources for patients about bullying.9,35 There currently are no rigorously-evaluated, effective primary-care-based bullying interventions. There are, however, school-based interventions, such as the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program, which have been shown to be effective in reducing bullying.4,36 Other potentially effective components of school-based programs include a well-enforced school anti-bullying policy, increasing student supervision, and parental involvement.4,36 Children who are identified in the primary-care setting can be referred for additional evaluation, counseling, and participation in effective school-based interventions. Children identified as at-risk for occasional bullying may reflect those who have tendencies towards bullying others.20 This may be a particularly important group to target for prevention. The smaller number of factors identified by RPA which, when combined, give the highest risk groups, may be more practical to use in identification.28 The risk profiles associated with any, moderate, and frequent bullying could guide potential intervention domains and tailoring of prevention messages.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of HBSC, which include the large sample size and breadth of topics covered, certain study limitations should be noted. The cross-sectional survey design precludes addressing causality. Future research could evaluate the predictive validity of the risk groups in an independent sample of children.28 Multivariable analysis results may identify more children who are likely to be bullies, whereas RPA will not identify all bullies, but may identify children with especially low and high risks for bullying. This study also did not examine different types of bullying, such as physical, verbal, and cyber-bullying; did not separately examine bullies, victims, and bully-victims; and did not stratify by gender (although gender was included as an independent variable in the multivariable and RPA analyses). Future research could examine whether separate models for these categories using RPA enhances risk-group identification. It is difficult to determine the directionality of association between parental involvement and bullying, as parents may have to come to school to talk with teachers as a result of their child’s problem behavior, rather than as a risk or protective factor. Given that this was a secondary data analysis, other potential risk factors for bullying, such as self-esteem,11 parental and peer attitudes about violence,37 child maltreatment,13,14 and domestic violence exposure,13 were not available in HBSC. The dataset relies on student self-report in a school-based sample, and therefore excludes students who are not enrolled in school. Bullying generally starts at a younger age than is examined in this sample, and the prevalence decreases with age3; therefore, the prevalence of bullying in a younger age group is likely to be higher than reported in this analysis.

Risk clusters for any, moderate, and frequent bullying were identified using RPA; risk factors for bullying were identified using multivariable analyses. Study findings from the multivariable analyses may be useful to providers in raising suspicion for bullying perpetration in patients who present with these risk factors, such as fighting, alcohol or drug use, smoking, or weapon-carrying. Special attention, however, should be given to children with clusters of factors identified by the RPA to assure that these highest-risk-group children are not missed. Children in the high-risk categories can be the focus of further evaluation and intervention. Bullying prevention, screening, and treatment interventions might be most effective when targeted at risk clusters, rather than individual risk factors in isolation.

WHAT’S NEW.

Risk factors and clusters differ for any, moderate, and frequent bullying. Weapon-carrying, smoking, and alcohol use are in the high-risk clusters for moderate and frequent bullying.

Bullying prevention, screening, and treatment interventions can focus on children in high-risk clusters.

Footnotes

Prior presentation: This study was presented in part as a platform presentation at the 2011 annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report. Dr. Shetgiri was supported by an NICHD Career Development award (1K23HD068401-01A1) and by Grant Number KL2RR024983, titled, “North and Central Texas Clinical and Translational Science Initiative” (Robert Toto, M.D., PI) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, et al. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olweus D. Bullying among schoolchildren: intervention and prevention. In: Peters RD, McMahon RJ, Quinsey VL, editors. Aggression and Violence Throughout the Life Span. London, England: Sage Publications; 1992. pp. 100–125. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olweus D. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smokowski PR, Kopasz KH. Bullying in school: an overview of types, effects, family characteristics, and intervention strategies. Child Sch. 2005;37(2):101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrington DP, Ttofi MM. Bullying as a predictor of offending, violence and later life outcomes. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2011;21(2):90–98. doi: 10.1002/cbm.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pepler D, Jiang D, Craig W, Connolly J. Developmental trajectories of bullying and associated factors. Child Dev. 2008;79(2):325–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craig WM, Pepler DJ. Identifying and targeting risk for involvement in bullying and victimization. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(9):577–582. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellegrini AD, Bartini M. An empirical comparison of methods of sampling aggression and victimization in school settings. J Educ Psychol. 2000;92(2):360–366. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sege RD, Wright JL, Smith GA, Baum CR, Dowd MD, Durbin DR. Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Policy statement: role of the pediatrician in youth violence prevention. Pediatrics. 2009;124:393–402. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trowbridge MJ, Sege RD, Olson L, O’Connor K, Flaherty E, Spivak H. Intentional injury management and prevention in pediatric practice: Results from 1998 and 2003 American Academy of Pediatrics periodic surveys. Pediatrics. 2005;116:996–100. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang S, Kim J, Kim S, Shin I, Yoon J. Bullying and victimization behaviors in boys and girls at South Korean primary schools. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(1):69–77. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000186401.05465.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sourander A, Helstela L. Persistence of bullying from childhood to adolescence – a longitudinal 8-year follow-up study. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(7):873–881. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowes L, Arseneault L, Maughan B, Taylor A, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. School, neighborhood, and family factors are associated with children’s bullying involvement: a nationally representative longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(5):545–553. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819cb017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shields A, Cicchetti D. Parental maltreatment and emotion dysregulation as risk factors for bullying and victimization in middle childhood. J Clin Child Psychol. 2001;30(3):349–363. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlyle KE, Steinman KJ. Demographic differences in the prevalence, co-occurrence, and correlates of adolescent bullying at school. J Sch Health. 2007;77(9):623–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR. School bullying among adolescents in the United States: Physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(4):368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nansel TR, Craig W, Overpeck MD, Saluja G, Ruan WJ Health-Behaviour in School-aged Children Bullying Analyses Working Group. Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviors and psychosocial adjustment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(8):730–736. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spriggs AL, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR, Haynie DL. Adolescent bullying involvement and perceived family, peer and school relations: commonalities and differences across race/ethnicity. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41(3):283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration. Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Health Behavior in School-Aged Children, 2001–2002 [United States] [Computer File]. ICPSR04372-v2. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2008. Jul 24, [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solberg ME, Olweus D. Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Aggress Behav. 2003;29:239–268. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borup I, Holstein BE. Does poor school satisfaction inhibit positive outcome of health promotion at school? A cross-sectional study of schoolchildren’s response to health dialogues with school health nurses. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(6):758–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnohr CW, Kreiner S, Due EP, Currie C, Boyce W, Diderichsen F. Differential item functioning of a family affluence scale: validation study on data from HBSC 2001/02. Soc Indic Res. 2008;89(1):79–95. [Google Scholar]

- 23.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 9.1 User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2004. [Accessed December 30, 2009]. http://support.sas.com/documentation/onlinedoc/91pdf/index_913.html. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feinstein AR. Multivariable Analysis: An Introduction. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1996. pp. 529–558. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Therneau TM, Atkinson EJ. An Introduction to Recursive Partitioning Using the RPART Routines. Rochester, NY: Mayo Foundation; 1997. p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su X, Azuero A, Cho J, Kvale E, Meneses KM, McNees MP. An introduction to tree-structured modeling with application to quality of life data. Nurs Res. 2011;60(4):247–255. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318221f9bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearson MR, Kholodkov T, Henson JM, Impett EA. Pathways to early coital debut for adolescent girls: a recursive partitioning analysis. J Sex Res. 2012;49(1):13–26. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.565428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fonarow GC, Adams KF, Abraham WT, Yancy CW, Boscardin WJ. Risk stratification for in-hospital mortality in acutely decompensated heart failure: classification and regression tree analysis. JAMA. 2005;293(5):572–580. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nansel TR, Overpeck MD, Haynie DL, Ruan WJ, Scheidt PC. Relationships between bullying and violence among US youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:348–353. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barker ED, Arsenault L, Brendgen M, Fontaine N, Maughan B. Joint development of bullying and victimization in adolescence: relations to delinquency and self-harm. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(9):1030–1038. doi: 10.1097/CHI.ObO13e31817eec98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR – Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States, 2009. Surveillance Summaries. MMWR. 2010;59(SS-5):1–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim MJ, Catalano RF, Haggerty KP, Abbott RD. Bullying at elementary school and problem behavior in young adulthood: a study of bullying, violence and substance use from age 11 to age 21. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2011;21(2):136–144. doi: 10.1002/cbm.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jessor R. Adolescent development and behavioral health. In: Matarazzo JD, Weiss SM, Herd AJ, Miller NE, Weiss SM, editors. Behavioral health. A Handbook of Health Enhancement and Disease Prevention. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elster A, Kuznets N. AMA Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS) Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleming M, Towey KJ, Limber SP, Gross RJ, Rubin M, Wright JL, Anderson SM, editors. Educational Forum on Adolescent Health: Youth Bullying. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farrington DP, Ttofi MM. School-based programs to reduce bullying and victimization. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2009;6:1–148. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens V, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Van Oost P. Relationship of the family environment to children’s involvement in bully/victim problems at school. J Youth Adolesc. 2002;31(6):419–428. [Google Scholar]